Abstract

Pretraining has laid the foundation for the recent success of deep learning in multimodal medical image analysis. However, existing methods often overlook the semantic structure embedded in modality-specific representations, and supervised pretraining requires a carefully designed, time-consuming two-stage annotation process. To address this, we propose a novel semantic structure-preserving consistency method, named “Review of Free-Text Reports for Preserving Multimodal Semantic Structure” (RFPMSS). During the semantic structure training phase, we learn multiple anchors to capture the semantic structure of each modality, and sample-sample relationships are represented by associating samples with these anchors, forming modality-specific semantic relationships. For comprehensive modality alignment, RFPMSS extracts supervision signals from patient examination reports, establishing global alignment between images and text. Evaluations on datasets collected from Shanxi Provincial Cancer Hospital and Shanxi Provincial People’s Hospital demonstrate that our proposed cross-modal supervision using free-text image reports and multi-anchor allocation achieves state-of-the-art performance under highly limited supervision. Code: https://github.com/shichaoyu1/RFPMSS

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Researchers are increasingly exploring large-scale multi-modal training to learn meaningful representations1. However, aligning different modalities remains challenging due to their inherent differences, potentially missing essential features for glioma diagnosis1,2. As shown in Fig. 1(a), early diagnosis relies on symptoms but ultimately depends on integrating MRI and pathology for conclusive results1.

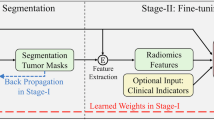

Motivation and Our Framework: (a) The practice of doctors in a clinical environment. (b) A semantic structure modeling strategy and a cross-supervised training strategy. The first focuses on modality-specific semantic structures. By optimizing many-to-many anchor assignments, it preserves modality-specific semantics within the input space. The second strategy uses a cross-supervised learning approach to further improve modality alignment. This text-driven supervision method cross-checks the relationships between imaging and textual modalities, aligning them within a shared semantic space. This reduces reliance on structured labels and improves multimodal co-representation.

The core of multi-modal fusion is semantic alignment across modalities. Recently, Multi-Modal Large Language Models (MLLMs)3 have shown remarkable ability to bridge this gap by combining textual reports with imaging data. These advancements, while promising, face hurdles due to annotation complexities, which demand extensive medical expertise4,5. Additionally, disease heterogeneity, data noise, and variability among medical practitioners contribute to reproducibility challenges and inconsistent clinical outcomes1.

In glioblastoma diagnosis, there are two main challenges in multi-modal information fusion. First, domain shifts between medical and natural images introduce noise, reducing diagnostic accuracy. Second, despite advances in self-supervised learning and representation transfer, issues such as limited datasets and inefficient labeling persist. Manual annotation remains complex and prone to errors, as annotators must account for spelling variants, synonyms, and abbreviations, often relying on NLP tools. Small mistakes in any step can lead to significant inaccuracies in label extraction, limiting scalability and accuracy.

Given the challenges mentioned, we propose a free-text report-driven review method based on Retaining Multi-Modal Semantic Structure (RFPMSS), as shown in Fig. 1(b), which demonstrates the overall workflow of our proposed approach. RFPMSS utilizes free-text reports for cross-modal alignment, eliminating the need for structured labels and enhancing modality fusion. This approach addresses the existing issues, ultimately improving diagnostic accuracy. Diagnosing glioblastoma is a challenging task, as single-modal data alone cannot provide a comprehensive diagnosis. As shown in Fig. 1(a), doctors need to combine imaging data and pathology text reports for an accurate assessment. To achieve this, as shown in Fig. 1(b), we employ two strategies: semantic structure modeling and cross-supervised training. The first strategy models modality-specific semantic structures by introducing “anchors” as proxies for latent representations. Through learning these anchors and modeling their associations with samples, we can represent both shared and unique concepts across samples, which enhances interpretability. By optimizing many-to-many anchor assignments, we maintain modality-specific semantics in the input space and achieve effective multimodal fusion in the joint embedding space, thereby improving diagnostic interpretability. Secondly, RFPMSS employs a cross-supervision learning strategy to further enhance modality alignment. During the pretraining phase, the method does not rely on structured labels. Instead, supervision signals are derived from radiology and pathology reports as free-text, which serve as the supervisory signals for modality alignment. This text-driven supervision method automatically cross-checks the relationships between image modalities and textual modalities, helping to align them in a shared semantic space, thereby improving the co-representation of multi-modal information. Moreover, the textual reports mitigate the dependence on structured labels by providing rich semantic content, enabling effective supervision without the need for explicit structured annotations, thus reducing reliance on manual labeling.

To demonstrate the effectiveness of our proposed approach, we trained our model on datasets collected from Shanxi Provincial People’s Hospital and Shanxi Cancer Hospital and tested it on multiple downstream zero-shot tasks. The results showed that our method achieved state-of-the-art performance across all settings, further underscoring the potential of RFPMSS in cross-modal medical image analysis.

In summary, our contributions are as follows:

-

We propose a novel anchor-based sample learning framework that preserves modality-specific semantic structures in a multimodal context. This enables effective semantic alignment and enhances the generalization capacity of cross-modal representations. By applying contrastive loss, our approach effectively addresses domain shift issues. Compared to standard multimodal information processing, this method improves glioma diagnosis accuracy and robustness across various clinical scenarios.

-

We introduce a text-driven modality alignment strategy that leverages free-text radiology and pathology reports to learn medical image representations, thereby mitigating the dependency on structured labels. The use of rich textual information not only alleviates the reliance on manual annotations but also provides strong supervisory signals for modality alignment, bridging the semantic gap between imaging and textual modalities.

-

Our method achieves superior performance over existing state-of-the-art multi-modal self-supervised representation learning approaches on both in-domain and out-of-domain datasets, demonstrating its robustness and effectiveness across various downstream tasks and clinical applications.

Related work

Multi-modal learning

With the emergence of large-scale multimodal datasets 6, multimodal learning has garnered extensive attention, spanning areas such as visual-language learning7,8 , visual-audio learning9,10,11, video-audio-language learning12 , zero-shot learning13, cross-modal generation14, and multimodal multitask learning15 . Miech et al.6 introduced a large-scale multimodal dataset composed of videos, audio, and text collected from YouTube without any manual annotations. It’s important to note that text is generated from audio using automatic speech recognition (ASR), and there exists noise alignment between text and video. They proposed a multimodal system showcasing the potential of learning video-text embeddings through contrastive loss. To handle noise in the dataset, 16 et al. introduced a method for noise estimation in multimodal data using multimodal density estimation. Miech et al.6 proposed a noise-contrastive estimation method in a multi-instance learning framework. XDC17 clustered audio–video for better feature learning in each modality. While some works focused on utilizing two modalities for multimodal learning, others explored using audio, video, and text together. A universal multimodal network18 was proposed to learn different embeddings for each modality combination. AVLNet12 aimed to learn a shared embedding mapping all modalities into a single joint space. Subsequently, MCN19 proposed learning a joint embedding through joint clustering and reconstruction. It’s worth noting that19 performs multimodal K-means clustering for learning hard semantic clusters. In contrast to the strict assignment in19, we propose flexible learning with multiple tasks separately for each modality. Recently, EAO20 utilized transformers and combination fusion modes to learn a joint embedding with contrastive loss.

Most of these works leverage contrastive or clustering losses on fused multimodal representations to learn a joint embedding space. However, this approach may fail to preserve modality-specific semantic structures among samples encoded by pre-trained modality-specific backbones, potentially compromising the model’s generalization ability. Recent research suggests that large-scale contrastive multimodal models like CLIP21 exhibit robustness to distribution shifts, mainly due to diverse large-scale training data and prompt engineering21 . Therefore, our focus is on making the pre-training objective robust to distribution shifts. In this regard, we propose a novel approach to preserve modality-specific semantic relationships in the joint embedding space by modeling relationships between samples. To achieve flexible relationship modeling between samples, we learn multiple anchor assignments for each sample, where shared anchors across samples capture commonalities, and different anchors between samples highlight uniqueness.

Sinkhorn-Knopp

In recent years, the Sinkhorn-Knopp algorithm22 has gained attention for its effectiveness in solving optimal transport problems23. Specifically,24proposed an entropically relaxed optimal transport problem that can be efficiently solved using the Sinkhorn matrix scaling algorithm. Much subsequent work has successfully leveraged the Sinkhorn-Knopp algorithm to solve different label assignment problems formulated as optimal transport. For instance, SeLa24 poses unsupervised clustering as a pseudo-label assignment problem and uses the Sinkhorn-Knopp algorithm to solve it. SeLaVi25 extends this idea to self-supervised representation learning on multimodal data, where exchanging cluster assignments between modalities encourages modality-invariant representation learning. Similarly, SwAV26 employs the Sinkhorn-Knopp algorithm for self-supervised representation learning, proposing to swap pseudo-labels between different augmentations of a sample, using soft assignments rather than hard pseudo-labels. In contrast to these works, SuperGlue27 uses the Sinkhorn-Knopp algorithm to solve correspondence problems between two sets of local features. Additionally, Sinkhorn-Knopp has been applied to detection problems28, for matching anchors to ground truths. More recently, UNO29 and TRSSL30 have successfully leveraged the Sinkhorn-Knopp algorithm to address novel class discovery and open-world semi-supervised learning, respectively. A key limitation of conventional Sinkhorn-Knopp algorithm is that it cannot be directly used to compute multiple assignments required for multi-anchor based learning.

Some previous work30 has attempted to address many-to-many matching problems indirectly. The authors of31 used an intermediate graph to match vertices between source and target graphs, but this intermediate graph was limited to group-to-group assignments and insufficient for the true many-to-many matching problem we aim to solve. 32modified the Sinkhorn-Knopp row and column constraints to obtain many-to-many assignments for modeling dense correspondence, however we find this approach performs poorly on multi-anchor matching problems. The modified Sinkhorn-Knopp constraint method produces suboptimal results, as discussed in Section “Visualization of RFPMSS”. To address these issues, we propose a new Multi-SK algorithm in this paper, which outperforms the improved Sinkhorn-Knopp constraint method and achieves true many-to-many matching.

Transformers in medical imaging

Transformers have achieved unprecedented success on natural language processing tasks33. Building on these advances, researchers have recently applied Transformers to computer vision, where they have surpassed the performance of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) on several tasks. This success has led the computer vision community to reconsider the dominance of CNNs. The medical imaging field has also seen increasing interest in Transformers, which can capture global context more effectively than CNNs that have only local receptive fields. Transformers show promise for medical image analysis by modeling long-range dependencies in images. Multimodal medical image fusion typically consists of intra-modality and inter-modality fusion. Inter-modality approaches aim to synthesize target images in order to capture useful structural information from source images of different modalities. Examples include translating between CT and MRI. Due to the challenges of inter-modal translation, only supervised approaches have been explored so far.

Dalmaz et al.34 introduced a new synthesis approach called ResViT for multi-modal imaging based on a conditional adversarial network with a ViT-based generator. ResViT employs both convolutional and transformer branches within residual bottlenecks to preserve local precision alongside global contextual sensitivity, leveraging the realism of adversarial learning. The bottlenecks comprise novel aggregated residual transformer blocks that synergistically retain local and global context, with weight sharing to minimize model complexity. ResViT was shown to be effective on two multi-contrast brain MRI datasets, BraTS35 and a multi-modal pelvic MRI-CT dataset36. Most transformer-based medical image synthesis methods use adversarial losses to generate realistic images. However, adversarial losses can lead to mode collapse, which requires effective strategies for mitigation37. In contrast, the proposed method in this work learns medical image representations directly from accompanying radiology and pathology reports using RFPMMS, then retains information conducive to cross-modal embedding learning and preserving modality-specific semantic structure. This effectively addresses the problem of mode collapse.

Method

Ethical Approval and Consent: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) of Shanxi Provincial People’s Hospital, Shanxi Province Cancer Hospital, and Fenyang Hospital of Shanxi Province. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardians prior to data collection and analysis. The data used in this study involved brain glioma imaging information and pathology reports from a cohort of patients treated at the above-mentioned hospitals.

Algorithm Overview: RFPMSS performs cross-supervised learning on top of a transformer-based backbone (termed Medical Image Transformer). As shown in Fig. 2 given a set of multimodal inputs \(\left\{ {I_{c}^{(i)} ,I_{m}^{(i)} ,I_{p}^{(i)} ,t^{(i)} } \right\}_{i = 1}^{N}\) for a patient’s study, we first forward its views to the Medical Image Transformer to extract view-relevant feature representations, where modality-specific projection functions are learned, denoted as \(f_{Ic}\),\(f_{{\text{Im}}}\),\(f_{Ip}\),\(f_{t}\),obtaining \(\hat{I}_{c}\),\(\hat{I}_{m}\),\(\hat{I}_{p}\),\(\hat{t}\) respectively. Where \(I_{c}^{(i)} ,\;{\text{I}}_{m}^{(i)} ,\;I_{p}^{(i)} ,\;t^{(i)\prime }\) respectively represent the CT images, MRI images, pathology images, and the corresponding diagnostic report for the i-th patient. Our goal is to optimize the parameters of ft, fv, fa such that they preserve the semantic structures between modality-specific samples in the joint embedding space while bringing semantically-related cross-modal inputs closer. Next, we perform cross-supervised learning, acquiring study-level supervision signals from free-text radiology reports. For this, it is necessary and imperative to use view fusion to obtain a unified visual representation for the entire patient study, as each radiology report is associated with a patient study but not with individual radiographs within the patient study. Then, this fused representation is used for two tasks in the pretraining stage: report generation and study-report representation consistency reinforcement. The first task supervises the training of the Medical Image Transformer using the free text from the original radiology reports. The second task reinforces the consistency between the visual representation of a patient study and the textual representation of its corresponding report. In Section “Modeling sample relationships via improved Sinkhorn-Knopp with anchors”, we propose a method to model relationships between samples using anchors, discussing the novel Multi-SK algorithm to learn these anchors for representing sample relationships, and then detail how the improved ViTs perform cross-supervised patient images and reports to obtain a unified feature representation in Section “Cross-supervised learning medical image transformer”. Finally, we propose the overall training objective to train the model in Section “Overall training objective of the model”.

Overview of the Proposed Model. Given weakly aligned radiological and pathological reports, CT images, MRI images, and pathological slice images of a patient, we first extract features using frozen modality-specific backbones (with the proposed medical image Transformers serving as the backbone in this work). These features are then passed through a token projection layer to obtain modality-specific input features \(\left( {lc,lm,lp,t} \right)\). Next, the modality-specific transformer models project the input features into a joint multi-modal representation space \(\left( {l\hat{c},l\hat{m},l\hat{p},\hat{t}} \right)\). The similarity between the input features \(\left( {lc,lm,lp,t} \right)\) and the input space anchors \(\left( {Z_{lc} ,Z_{lm} ,Z_{lp} ,Z_{t} } \right)\), as well as the projected features \(\left( {l\hat{c},l\hat{m},l\hat{p},\hat{t}} \right)\) and the projected space anchors \(\left( {\hat{Z}_{lc} ,\hat{Z}_{lm} ,\hat{Z}_{lp} ,\hat{Z}_{t} } \right)\), is calculated. Our Multi-SK algorithm (M(.)) is then employed to optimize the assignment of multiple anchors for each sample, as illustrated by the input space assignment (projection space assignment). This process is performed for each modality, with the corresponding consistency loss enforced; however, for simplicity, only the modality-specific consistency loss for text anchors and cross-modal consistency between the patient report text and pathological slice image modalities are depicted in this figure. LN and MHSA represent LayerNorm and Multi-Head Self-Attention, respectively.

Modeling sample relationships via improved Sinkhorn-Knopp with anchors

We aim to improve the generalization capability of cross-modal models on unseen data by flexibly modeling the relationships between samples, i.e., \(x^{(i)}\), \(x^{(j)}\), from a particular modality using anchors, while preserving the semantic structures between modality-specific samples. Specifically, we learn multiple anchors for each sample, where the similarity of assignments over these anchors represents the relationship to be preserved between samples from a particular modality. By enforcing consistency in anchor assignments before and after projecting features to the joint embedding space, we preserve the modality-specific semantic structures. To address the challenge of unsupervised anchor discovery, we cast it as a many-to-many label assignment optimal transport problem with a uniform prior and propose the Improved Sinkhorn-Knopp algorithm. Here, the sample-to-anchor similarities encode sample relationships, with the top K anchors effectively modeling relationships for each sample(\(z = \left\{ {z^{(i)} } \right\}_{i = 1}^{K}\) represents the learned anchors before transformation,\(\hat{z} = \left\{ {\hat{z}^{(i)} } \right\}_{i = 1}^{K}\) represents the learned anchors after transformation). Preserving such modality-specific semantic structures in the joint space boosts the cross-modal model’s generalizability.

Given a sample matrix \(G\) s.t.\(G \in {\mathbb{R}}^{N \times d}\) representing N samples and an anchor matrix \(Z\) s.t. \(Z \in {\mathbb{R}}^{K \times d}\) of K anchor vectors, we compute a similarity matrix \(X\) s.t.\(X = G \cdot Z^{\top}\) and \(X \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{R}}}^{N \times K}\). This similarity matrix provides information on the relationships between samples and anchors, serving as a foundation for subsequent allocation strategies. The goal is to identify an anchor assignment matrix \(P\) that precisely allocates each sample to \(K^{\prime}\) anchors while ensuring uniform distribution across different anchors i.,e each anchor must be selected exactly \(N \times K^{\prime}/K\) times.

To compute the multi-anchor assignments for each sample, we introduce an alternative 3D matrix \(P^{\prime}\) s.t.\(P^{\prime} \in {\mathbf{\mathbb{R}}}^{K \times N \times K}\). We augment the dimensionality of the previously mentioned similarity matrix \(X\) to 3D by adding a depth dimension, resulting in a 3D similarity matrix \(X^{\prime}\) with K channels, shaped as \(K \times N \times K\). Each channel is a scaled version of \(X\), with channels having a predefined ranking to enable top-\(K^{\prime}\) anchor selection. Since we are interested only in selecting the top \(K^{\prime}\) anchors, we set the first \(K^{\prime}\) channels of \(X^{\prime}\) to be the same as \(X\). The remaining \(K - K^{\prime}\) channels are set to \(\mu X\), where \(\mu\) is a damping factor s.t.\(0 < \mu < 1\), assisting in the selection of the top \(K^{\prime}\) anchors for each sample.

The optimization objective of multi-allocation Sinkhorn-Knopp is to identify an allocation matrix \(P^{\prime}\) that satisfies our multi-anchor allocation constraints while maximizing similarity with the initial allocation/similarity matrix \(X^{\prime}\). The optimization problem is defined as minimizing the distance \(d_{X}^{\lambda } \left( {Z,G} \right)\).

\(P^{ * }\) can be obtained through the following algorithm:

Algorithm 1 Computation \(d_{X}^{\lambda } \left( {Z,G} \right)\) and \(P^{ * }\) of using Sinkhorn-Knopp’s fixed point iteration.

The final 2D assignment matrix \(P\) is computed by performing a depth-wise sum on the top \(K^{\prime}\) channels.

Cross-supervised learning medical image transformer

In the backbone of the architecture, the Medical Image Transformer receives image patches as input. The multi-modal medical images are processed into patches by dividing each patient’s corresponding CT, MRI, and histopathology images into a 14 × 14 grid of cells, each containing 16 × 16 pixels. For example, considering MRI images, each image patch is flattened into a one-dimensional pixel vector and then fed into the transformer. At the start of the transformer, a patch embedding layer linearly transforms each one-dimensional pixel vector into a feature vector. This vector is concatenated with position embeddings generated through learnable positional encoding to capture the relative position of each patch within the entire input patch sequence. The concatenated features are then passed through another linear transformation layer to match the dimension of the final medical image features. At the core of the Medical Image Transformer, we stack 12 self-attention blocks with identical architecture but independent parameters (Fig. 3a). The self-attention block is designed following the approach in33 and is repeated multiple times. In each block, layer normalization38 is applied before the multi-head attention and perceptron layers, and residual connections are added afterward to stabilize the training process. In the perceptron layer, we employ the Mish activation function39 instead of the linear unit (ReLU)40. Given the need for more detailed image information in patient imaging data to capture tumor features, we introduce an aggregation embedding that aggregates information from different input features. As depicted in Fig. 1b, in the final layer, we perform iterative concatenation, repeatedly concatenating the learned aggregation embedding with the learned representation of each patch. This approach differs from the operation in the Vision Transformer (ViT)41, which connects the aggregation embedding with patch features only once. This repeated concatenation more thoroughly represents patient imaging details, providing richer information for tumor feature extraction.

Workflow of RFPMSS. In this figure, we outline the workflow of the RFPMSS (Radiology and Pathology Multi-modal Semantic Space) model: forwarding radiographs of the k-th patient study through the medical image transformers, fusing representations from different views using an attention mechanism, and leveraging the information in radiology reports through report generation and study-report representation consistency reinforcement. Section (b) provides an overview of the entire workflow. Section (a) illustrates the architecture of the medical image transformers. In Section (c), \(v^{k}\) and \(t^{k}\) represent the visual and textual features of the k-th patient study, respectively. \(\hat{c}_{1:T}^{k}\) and \(c_{1:T}^{k}\) denote the token-level predictions and ground truth for the k-th radiology report of length T.

As described above, we utilize the Medical Image Transformer to simultaneously process all CT, MRI, and histopathology images in a patient’s study to obtain their individual representations. We further employ attention mechanisms to fuse these individual representations to obtain an overall representation of the given study. As shown in Fig. 3(b), assuming a study comprises three sets of radiographic images (i.e., views), namely CT, MRI, and histopathology images, we first concatenate the features of all views. Subsequently, the concatenated features are input to a multi-layer perceptron to compute attention values for each view. Next, we normalize these attention values using the softmax function, which serves as weights to generate weighted versions of individual representations. Finally, these weighted representations are concatenated to form a unified visual feature describing the entire study. The decoder of the Report Transformer is applied to the unified visual feature \(v^{k}\) of the k-th patient study to reproduce its corresponding imaging reports, denoted as \(c_{1:T}^{k}\). Here, \(c_{1}^{k}\) represents the sequence start token, and \(c_{T}^{k}\) represents the sequence end token. As a result, the Report Transformer generates a series of token-level predictions \(\hat{c}_{1:T}^{k}\) for the k-th patient study. The prediction of the t-th token in this sequence depends on the predicted subsequence \(\hat{c}_{1:t - 1}^{k}\) and the visual feature \(v^{k}\). The network architecture of the Report Transformer follows the architecture of the decoder in33. We aim for the predicted token sequence (\(\hat{c}_{1:T}^{k}\)) to be similar to the sequence of the original reports representing the k-th patient study (\(c_{1:T}^{k}\)). Therefore, as shown in Fig. 3c, we apply language modeling loss to \(\hat{c}_{1:T}^{k}\) and \(c_{1:T}^{k}\) to maximize the log-likelihood of tokens in the original reports.

where \(\hat{c}_{1:t - 1}^{k}\) is a special symbol indicating the start of the predicted sequence, \(\phi_{v}\) and \(\phi_{t}\) stand for the parameters of the Medical Image transformer and report transformer, respectively.

Overall training objective of the model

During the model training stage, we aim to accomplish two tasks. The first task is to ensure the semantic structure of each modality by computing the consistency loss of anchor point allocation between the input and output joint embedding spaces. The second task is to enforce cross-modal representation by employing contrastive loss, thereby enhancing the consistency of research reports.

Loss of semantic consistency between multimodal medical images and reports To maintain the semantic structure of each modality, we utilize consistency loss to enforce similar anchor point allocation between the input and joint embedding spaces. Since the cross-modal contrastive loss in the joint embedding space attempts to integrate different modalities, features from specific modalities in the joint embedding space should retain common anchor points present in the corresponding features of other modalities. Therefore, we also apply cross-modal anchor consistency across all modalities, resulting in nine consistency constraints given that we are dealing with three input modalities.

We denote \({\mathcal{L}}({\mathbf{t}},\hat{I}_{c} ,{\mathbf{z}}_{t} ,{\hat{\mathbf{z}}}_{t} )\) as the consistency loss between the anchor point allocation of the report in the input space and the corresponding CT image feature in the joint embedding space, as shown in Eq. 5.

In the equation, \({\mathbf{z}}_{t}\) and \({\hat{\mathbf{z}}}_{t}\) represent the input and output learnable anchor point vectors for the text modality, respectively.\(g\left( \cdot \right)\) and \(M\left( \cdot \right)\) denote the binary cross-entropy-with-logits loss and the multi-assignment Sinkhorn-Knopp (as discussed in Section “Cross-supervised learning medical image transformer”), respectively.\(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) represent the loss coefficients, and \(sim(a,b) = \exp \left( {\frac{a \cdot b}{{\tau |a||b||}}} \right)\), where \(\tau\) is the temperature hyperparameter for similarity measurement. The overall semantic structure preservation of all modalities’ consistency loss is defined as:

Contrastive loss for modality representation alignment We employ a contrastive loss42 for aligning cross-modal representations. Here, we denote by \(t^{k}\) the text feature vector of the k-th radiological examination report. In practice, we obtain tk by forwarding the token sequence from the k-th report (i.e.,\(c_{1:T}^{k}\)) through the BERT (i.e., Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) model43. BERT is built upon the encoder architecture presented in33 and is pretrained on a large corpus of textual data, enabling it to generate universal text representations for input reports. Assuming we have B patient studies in each training minibatch, as depicted in Fig. 3c, the contrastive loss for the k-th study can be expressed as:

where \(cos\left( { \cdot , \cdot } \right)\) means the cosine similarity, \(\cos ({\mathbf{v}}^{k} ,{\mathbf{t}}^{k} ) = \frac{{({\mathbf{v}}^{k} )^{\top} {\mathbf{t}}^{k} }}{{\left\| {{\mathbf{v}}^{k} } \right\|\left\| {{\mathbf{t}}^{k} } \right\|}}\), \({\top}\) denotes the transpose operation, \(\left\| \cdot \right\|\) stands for L2 normalization, \(\tau\) and is the temperature factor. For each patient study, we simply aggregate \({\mathcal{L}}_{{{\text{contrast}}}}^{k}\) and \({\mathcal{L}}_{{{\text{language}}}}^{k}\) as the overall loss. During the fine-tuning stage, we typically employ cross-entropy loss for model adjustments.

We further utilize contrastive loss to bring cross-modal embeddings of the same sample closer while pushing apart embeddings from other samples. To achieve this, we employ four pairs of single-modal constraint losses between \(\left( {I_{c} ,I_{m} } \right)\),\(\left( {I_{m} ,I_{p} } \right)\),\(\left( {I_{m} ,t} \right)\) and \(\left( {I_{p} ,t} \right)\), denoted as \({\mathcal{L}}_{{nce\_I_{c} I_{m} }}\), \({\mathcal{L}}_{{nce\_I_{m} I_{p} }}\),\({\mathcal{L}}_{{nce\_I_{m} t}}\) and \({\mathcal{L}}_{{nce\_I_{p} t}}\), respectively. Specifically, we leverage noise contrastive estimation44 and a temperature parameter \(\kappa\) to formulate these losses.

The overall contrastive loss for all modalities is defined as

Overall Loss The overall training objective is a combination of the SSPC loss (Eq. 6 ) and the contrastive loss(8):\({\mathcal{L}}_{f} = \lambda_{sspc} {\mathcal{L}}_{sspc} + \lambda_{nce} {\mathcal{L}}_{nce}\), where \(\lambda_{sspc}\) and \(\lambda_{nce}\) are the loss coefficients. By combining these two losses, the model learns a more generalized joint embedding space that preserves modality-specific semantic structures by enhancing the similarity of anchor point assignments before and after feature projection, and combines representations of different modalities using contrastive loss.

Experiments

In this section, we evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed RFPMSS network for multimodal medical information fusion tasks. Section “Experimental setup” presents the experimental setup, including datasets, evaluation metrics, and implementation details. Section “Comparison with state-of-the-art” introduces the quantitative and qualitative results of the multimodal medical information fusion task. In Section “Visualization of RFPMSS”, we visualize the joint multimodal features and semantic structures to demonstrate the semantic structure retention of the proposed algorithm. Finally, Section “Ablation studies” discusses and conducts an ablation study on several key components.

Experimental setup

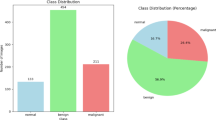

Datasets We trained our model using the BraTS2021 dataset45 and the UPENN-GBM dataset46. The BraTS2021 dataset comprises 8,160 MRI scans from 2,040 patients, each including four modalities of MR images: T1, T1Gd, T2, and T2-FLAIR. The annotations in BraTS2021 primarily consist of enhancing tumor (ET), peritumoral edema/infiltrating tissue (ED), and necrotic tumor core (NCR). The UPENN-GBM dataset includes multiparametric MRI (mpMRI) scans of newly diagnosed glioblastoma (GBM) patients, along with patient demographics, clinical outcomes (e.g., overall survival, genomic information, tumor progression), and computer-assisted and manually corrected segmentation labels of histologically distinct tumor subregions and whole brain segmentations. To address the lack of data on clinical diagnostics and pathology reports, we collected and constructed a dataset from Shanxi Provincial People’s Hospital, Shanxi Cancer Hospital, and Shanxi Fenyang Hospital, comprising information from a total of 1,016 patients. This dataset (EndocrinePatientData) includes imaging data such as CT, MR, and pathological slices, as well as valuable imaging and pathological diagnostic reports corresponding to these patients.

Parameter settings In the pre-training phase, we resized each radiographic image from the source domain to 256 × 256 pixels, followed by random cropping to produce 224 × 224 images. Data augmentation techniques such as random horizontal flipping, random rotation (between -10 and 10 degrees), and random grayscaling (adjusting brightness and contrast) were applied to generate enhanced images. When using random horizontal flipping, we accordingly adjusted the “left” and “right” terms in the accompanying radiology reports.

During the fine-tuning phase, the same data augmentation strategies were applied to all four target domain datasets: random cropping, random rotation, random grayscaling, and random horizontal flipping. As in the pre-training phase, each radiograph in the target domain was resized to 256 × 256, followed by cropping and augmentation to generate 224 × 224 radiographs for input images.

Following the methodologies of 12,19,20, we employed gated linear projection47 to project features into a common label space and mapped the generated labels into a shared embedding space. The dimensionality of the common label space was set to 4096, and the dimensionality of the shared embedding space was set to 6144. We utilized a single Transformer block with a hidden layer size of 4096, 64 heads, and an MLP size of 4096. The number of anchors \(K\) was set to 64, \(K^{\prime}\) was set to 32, and the damping coefficient \(\mu\) was set to 0.25.

All models were trained using the Adam optimizer48 for 15 epochs, with a learning rate of 5e-5, an exponential decay rate of 0.9, and a cosine similarity temperature \(\left( \tau \right)\) of 0.1. During the execution of Multi-SK, we maintained a repository of size 5500. As per18,20, we assigned a higher weight to the loss terms involving patient reports in Eq. (6), setting the weight for all text report terms to 1.0, and the remaining weights to 0.1.

Comparison with state-of-the-art

Image-to-Image Tasks In Table 1, we summarize the performance of RFPMSS on four zero-shot image retrieval tasks using the BraTs2021 and UPENN-GBM datasets: MRI-to-CT, CT-to-MRI, pathology-to-MRI, and pathology-to-CT retrievals. Our method consistently outperforms state-of-the-art models, particularly excelling in pathology-to-imaging tasks with a 3% median rank improvement on BraTs2021. RFPMSS also surpasses leading self-supervised7,17,49,50 and transfer learning models, outperforming C2L50 and TransVW7 by at least 2% with limited labels and maintaining at least a 4% advantage as labeling increases (Table 2).

Text-to-Image Tasks For text-to-image retrieval, we unified radiological examination reports and pathological detection reports based on their textual content and retrieved corresponding imaging pictures (MRI and CT images). Our method improved the median and mean rank of the baseline20 by 3% on the BraTs2021 dataset, with corresponding increases in recall metrics R@5 and R@10. For image-to-examination report retrieval, our method performed exceptionally well on the BraTs2021 dataset, showing a 3% improvement and a 2.2% increase in R@5 on the UPENN-GBM dataset. Similarly, our proposed method outperformed the current state-of-the-art methods in most text-to-image and image-to-text retrieval metrics. In Table 3, we report the results of the text-to-whole-image retrieval task, where our method achieved improvements of 2.2% and 2.7% in R@1 and R@5, respectively, over previous studies.

Figure 4 demonstrates that RFPMSS produces accurate attention regions on MRI slices, identifiable by applying a fixed confidence threshold, as shown by green boxes that align well with radiologist annotations (red boxes), with an IoU mostly above 0.5. This suggests that RFPMSS’s attention regions correspond closely with clinical diagnoses. Additionally, RFPMSS consistently outperforms label-supervised pretraining methods, like the Transformer-based LSP, particularly at lower labeling rates. For instance, using BraTs2021 and UPENN-GBM datasets as the target, RFPMSS achieved approximately 2.5% improvement when fewer than 5,000 training images were available.

Visualization of 10 Randomly Selected Samples from the EndocrinePatientData Dataset. This figure presents the visualization of 10 randomly selected samples from the EndocrinePatientData dataset, after fine-tuning with all annotated training data. For each sample, both the original image (left) and the attention map generated by RFPMSS are displayed. In each original image, the red boxes highlight the lesion areas annotated by radiologists and pathologists. In the attention maps, red indicates the attention values generated by RFPMSS, with deeper red representing higher confidence for specific diseases. The green boxes in the original images depict the predicted lesion areas, generated by applying a fixed confidence threshold to the attention maps.

These improvements indicate that raw radiology and pathology reports contain more useful information than manually assisted structured tags. In other words, the advantages our method demonstrates with small-scale target domain training data can be attributed to the rich information carried by radiology reports in the source domain. This additional supervision helps learn transferable radiograph representations, whereas the supervisory signal from structured tags carries less information. We believe this represents an important step towards using natural language descriptions as a direct supervisory signal for image representation learning.

Visualization of RFPMSS

To provide a clearer understanding of our method’s application and its effects, we have added Fig. 5, which visually illustrates the impact of our semantic structure-preserving cross-supervision method across multiple modalities. This figure captures the semantic structure distribution in CT scans, MRI images, pathology slides, and associated textual reports. Specifically, anchor assignments in part d of Fig. 5 emphasize how these modalities map onto shared semantic structures, revealing notable similarities in their representation of tumor features.

The visualization of semantic structure preservation. Part a shows the fully integrated features, part b focuses on image features, and part c highlights the features from textual reports.Part d shows the anchor distributions, demonstrating a high degree of similarity for tumor-related structures across modalities.

In more detail: Part a presents the integrated, multi-modal features after cross-supervision has aligned information from all modalities, showcasing how our approach effectively synthesizes image and text data to preserve semantic integrity across modes. Part b isolates the contributions from imaging features, focusing on the representation derived solely from visual data (CT and MRI scans), which helps illustrate how each modality alone captures unique aspects of tumor characteristics. Part c highlights features from textual reports, offering insight into how descriptive data from medical reports aligns with the visual data. This alignment underscores the model’s ability to bridge textual and visual inputs for a cohesive representation.

Together, these parts underscore our model’s capacity to maintain high consistency across different data types and modalities, enhancing its reliability in cross-modal tumor analysis and reinforcing its potential in clinical diagnostics. Figure 5 visually substantiates these findings, showing how semantic structure is not only preserved but also effectively aligned across different information channels, resulting in more accurate and interpretable representations of glioma features.

Ablation studies

Individual training vs. joint training

For RFPMSS, a key question is whether jointly trained RFPMSS performs better than modality-specific RFPMSS. To address this, we compared the performance of individually trained RFPMSS against jointly trained RFPMSS in Table 3. In individual training, the model only has access to its own data; in joint training, the model is trained on all data combined. On two image-text tasks, BraTs2021 and UPENN-GBM, the individually trained and jointly trained models achieved comparable results. However, on the UPENN-GBM and our own dataset, the individually trained image and image models performed significantly worse than the jointly trained models. This suggests that joint training greatly benefits data-scarce modalities (such as audio and video) by allowing cross-modal knowledge transfer (e.g., from reports).

Impact of loss functions

We report the results of this ablation in Table 4(a). In the first row, we report the results using reconstruction loss and contrastive loss, noting a 2% performance drop across all metrics when using reconstruction loss. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed SSPC loss. In the second row, we report results without the proposed cross-modal SSPC loss (‘w/o CM SSPC’), which brings cross-modal representations closer in the joint embedding space to achieve better performance in zero-shot cross-modal tasks. Removing the cross-modal SSPC loss significantly reduced zero-shot retrieval performance on the MSR-VTT and YouCook2 datasets, with R@5 performance dropping by 2.4% and 2.5%, respectively. This empirically validates the effectiveness of the cross-modal SSPC loss in achieving better cross-modal representations. In the third row, we analyze the impact of the proposed SSPC loss (‘w/o SSPCL’) by removing the anchor consistency between modality-specific and joint embedding spaces. Instead, we enforce anchor assignment before Multi-SK to align with anchors optimized by Multi-SK from the same embedding space. We also apply cross-modal SSPC loss to isolate its impact on feature projection. Removing anchor consistency significantly reduced zero-shot retrieval performance (R@5 by about 1.5%), indicating the importance of SSPC loss in maintaining modality-specific semantic structures in the joint embedding space for better performance.

Types of medical image transformers

We investigated the impact of replacing the medical image transformer (Table 2). Replacing the radiograph transformer with ResNet-10151 resulted in a roughly 7% drop in overall performance on the BraTs2021 image dataset. This comparison shows that the radiograph transformer is more effective at handling limited annotations, as validated by the results in Tables 2. Next, replacing the radiograph transformer with the original ViT architecture without recurrent connection operators resulted in a 3.3% drop in overall performance. This result validates the usefulness of recurrently connecting learned aggregated embeddings with block representations. We also observed a 3.8% performance difference between ResNet-based and ViT-based architectures, highlighting the advantages of transformer-like architectures.

Impact of the number of anchors

To analyze the impact of the number of anchors, we experimented with different numbers of anchors \(K\) and selected anchors \(K^{\prime}\). We report the results in Table 4(b) and Fig. 6. Our experiments on the BraTs2021 and UPENN-GBM datasets showed that our proposed method’s performance improved with an increasing number of anchors, as expected, since more anchors provide higher representation learning capacity. We also observed that the method performed quite well even with very few anchors, demonstrating the overall effectiveness of our proposed solution. However, as we selected more anchors, the performance increased up to a point; selecting too many anchors (48 out of 64 in this experiment) introduced additional constraints, leading to suboptimal performance.

Impact of cross-supervised learning on results

First, we removed the view fusion module so that different radiographs in patient studies were associated with the same study-level radiological and pathological reports (row 3). This operation is counterintuitive since each radiograph alone cannot provide enough information to generate a study-level report. Comparing rows 3 and 0, we found that removing the view fusion module reduced performance on the UPENN-GBM image dataset by nearly 2%. This result indicates that learning study-level pretrained representations is superior to image-level pretraining since the former contains more patient-level information. Next, replacing cross-supervised learning with label-supervised learning (row 4) degrades RFPMSS to LSP (Transformer) in Table 2. We found that abandoning both report-related tasks had a 2% adverse impact on performance. Lastly, we separately studied the two report-related learning tasks. Comparing row 0 with rows 5 and 6, we observed that removing either task did not significantly affect overall performance (around 1%). This result suggests partial overlap in the effects of the two tasks. Nonetheless, either task and the view fusion module still outperformed LSP (Transformer) (row 4). Additionally, while both tasks improved overall performance, reinforcing consistency between representations of each patient study and its associated reports (the second task) was more important than report generation (the first task). The reason could be that representations learned in the second task can be viewed as summaries of each report, providing more global information than token-level predictions in the first task. This advantage makes the second task more beneficial for learning better study-level radiograph features containing more study-level information.

More about RFPMSS

We performed a comprehensive ablation study on RFPMSS by selectively removing or replacing individual modules, as shown in Table 5

First, we assessed the impact of replacing the radiography transformer (Table 5, rows 1–2). When we substituted the radiography transformer with ResNet-101 (row 1), RFPMSS’s performance on the EndocrinePatientData image dataset dropped by approximately 7% (compared to row 0), highlighting the radiography transformer’s effectiveness with limited annotations. Replacing it with the base ViT architecture without cyclic connection operators (row 2) reduced overall performance by 3.3%, confirming that cyclically linking learned aggregate embeddings to patch representations aids performance. The ResNet and ViT-based architectures also showed a 3.8% performance difference (rows 1 and 2), indicating the benefit of Transformer-like architectures.

Beyond the medical image transformer, we also examined the effect of cross-supervised learning. First, we removed the view fusion module so that individual radiographs in a patient study were associated with the same study-level radiology report (row 3). Comparing row 3 with row 0, removing this module reduced performance by 2%, indicating that study-level pretraining is more advantageous than image-level pretraining due to the added patient-level information.

Subsequently, we replaced cross-supervised learning with label-supervised learning (row 4), resulting in a 2% performance drop. Lastly, we analyzed the individual impact of two report-related learning tasks. Comparisons between row 0 and rows 5 and 6 indicated a modest 1% performance reduction when either task was removed, suggesting partial redundancy. However, each task, alongside the view fusion module, outperformed the LSP (Transformer) baseline (row 4). We also observed that the task enforcing consistency between each patient study and its corresponding report was more beneficial than report generation alone, likely because it captures a more comprehensive summary of each report, improving study-level radiographic feature learning.

Qualitative analysis

We first conducted a fine-grained visual analysis of the learned anchors. In Fig. 7, we present a detailed analysis of these learned anchors. For the analysis, we visualized the anchor assignments as binary distributions. However, during training, we used soft anchor assignments. In Fig. 7(c), we compared the anchor assignments of samples from similar categories. It can be seen that even though the patients’ radiographs belong to different categories, they are visually similar, and the anchor assignments for these two examples capture this similarity. In Fig. 7(f), we compared the anchor assignments of images from different categories of patient modalities. It can be observed that the anchor assignments are significantly different from what one might expect. This further validates our assertion that the proposed method can assign semantically meaningful anchors without any explicit supervision.

Anchor Point Assignments Demonstrating Visual Similarity in the EndocrinePatientData Dataset. This figure illustrates the anchor point assignments that demonstrate the visual similarity between image samples within the EndocrinePatientData dataset. It includes two related categories—(a) CT brain images and (b) MRI brain images—as well as two different categories—(d) CT brain images and (e) CT lung images. The visual similarity is also reflected in the anchor point assignments in (c), where most assigned anchors are similar, with only slight differences. This showcases the flexibility and effectiveness of our method. Conversely, samples (d) and (e) appear very different, which is reflected in their significantly different anchor point assignments, as shown in (f). Green cells represent assigned anchors, yellow cells represent unassigned anchors, and differences in anchor assignments are highlighted in red.

Limitation

The proposed cross-supervised learning approach in this study effectively reduces noise from domain shifts and minimizes dependence on structured labels, improving glioblastoma diagnostic accuracy. However, some limitations remain. One challenge is learning or discovering semantic structure anchors in an unsupervised way. Currently, anchor discovery is treated as a uniform label assignment task, with equal sample distribution per anchor. A more adaptive approach would be to train these assignments dynamically, which could be a direction for future research. Further improvements could focus on leveraging attention mechanisms to better capture context and integrating temporal sequences with multi-view spatial data, which could enhance the model’s clinical applicability in early screening, prevention, and treatment of glioblastoma.

Conclusion

We propose a novel method that preserves modality-specific semantic relationships between samples in a joint multi-modal embedding space while learning medical image representations from accompanying radiological and pathological reports. This approach reduces manual standards and improves learning efficiency. To achieve this, we introduce a flexible sample relationship modeling method that assigns multiple anchors to each sample, capturing both shared and unique aspects of the samples. To obtain these assignments, we developed a novel Multi-Assignment Sinkhorn-Knopp (Multi-SK) algorithm and used a proposed anchor consistency loss to learn these anchors. Unlike manual priors used in other networks, we derive image representations of radiological images from textual reports, making our method more adaptable to multi-modal content. Our qualitative results demonstrate that the learned anchors correspond to meaningful semantic concepts and outperform self-supervised learning and transfer learning on natural source images in generating more transferable representations. Our extensive experiments show that the proposed method improves generalization by surpassing state-of-the-art methods on both in-domain and out-of-domain datasets. We also demonstrate that our method achieves state-of-the-art performance on multiple zero-shot tasks and excels when fine-tuned on downstream datasets.

Data availability

Data Availability Statement: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during this study contain sensitive medical information and, therefore, are not publicly available. However, the data can be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, subject to approval from the relevant institutions.

References

Waqas, A., Tripathi, A., Ramachandran, R. P., Stewart, P. A. & Rasool, G. Multimodal data integration for oncology in the era of deep neural networks: A review. Front. Artif. Intell. 7, 1408843 (2024).

Mandal, S. et al. Artificial intelligence and deep learning in revolutionizing brain tumor diagnosis and treatment: A narrative review. Cureus https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.66157 (2024).

Carolan, K., Fennelly, L. & Smeaton, A. F. A Review of Multi-Modal Large Language and Vision Models. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/2404.01322 (2024).

Yin, S. et al. A Survey on Multimodal Large Language Models. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/2306.13549 (2024).

Cui, C. et al. A survey on multimodal large language models for autonomous driving. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision 958–979 (2024).

Miech, A. et al. Howto100m: Learning a text-video embedding by watching hundred million narrated video clips. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision 2630–2640 (2019).

Haghighi, F., Taher, M. R. H., Zhou, Z., Gotway, M. B. & Liang, J. Transferable visual words: Exploiting the semantics of anatomical patterns for self-supervised learning. IEEE Trans. Med. Imag. 40, 2857–2868 (2021).

Zhang, P. et al. Vinvl: Revisiting visual representations in vision-language models. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition 5579–5588 (2021).

Chen, L. et al. Self-supervised learning for medical image analysis using image context restoration. Med. Image Anal. 58, 101539 (2019).

Arandjelovic, R. & Zisserman, A. Look, listen and learn. in Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision 609–617 (2017).

Aytar, Y., Vondrick, C. & Torralba, A. Soundnet: Learning sound representations from unlabeled video. Advances in neural information processing systems 29, (2016).

Rouditchenko, A. et al. AVLnet: Learning Audio-Visual Language Representations from Instructional Videos. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/2006.09199 (2021).

Mancini, M., Naeem, M. F., Xian, Y. & Akata, Z. Open world compositional zero-shot learning. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition 5222–5230 (2021).

Reed, S. et al. Generative adversarial text to image synthesis. in International conference on machine learning 1060–1069 (PMLR, 2016).

Kaiser, L. et al. One model to learn them all. arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.05137 (2017).

Amrani, E., Ben-Ari, R., Rotman, D. & Bronstein, A. Noise estimation using density estimation for self-supervised multimodal learning. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 35, 6644–6652 (2021).

Alwassel, H. et al. Self-supervised learning by cross-modal audio-video clustering. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 9758–9770 (2020).

Alayrac, J.-B. et al. Self-supervised multimodal versatile networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 25–37 (2020).

Chen, B. et al. Multimodal clustering networks for self-supervised learning from unlabeled videos. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision 8012–8021 (2021).

Shvetsova, N. et al. Everything at once-multi-modal fusion transformer for video retrieval. in Proceedings of the ieee/cvf conference on computer vision and pattern recognition 20020–20029 (2022).

Fang, A. et al. Data Determines Distributional Robustness in Contrastive Language Image Pre-training (CLIP). in Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning (2022).

Sinkhorn, R. & Knopp, P. Concerning nonnegative matrices and doubly stochastic matrices. Pacific J. Math. 21, 343–348 (1967).

Brenier, Y. Décomposition polaire et réarrangement monotone des champs de vecteurs. CR Acad. Sci. Paris Sér. I Math. 305, 805–808 (1987).

Distances, C. M. S. Lightspeed computation of optimal transport. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 26, 2292–2300 (2013).

Asano, Y., Patrick, M., Rupprecht, C. & Vedaldi, A. Labelling unlabelled videos from scratch with multi-modal self-supervision. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 4660–4671 (2020).

Caron, M. et al. Unsupervised learning of visual features by contrasting cluster assignments. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 9912–9924 (2020).

Sarlin, P.-E., DeTone, D., Malisiewicz, T. & Rabinovich, A. Superglue: Learning feature matching with graph neural networks. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition 4938–4947 (2020).

Ge, Z., Liu, S., Li, Z., Yoshie, O. & Sun, J. Ota: Optimal transport assignment for object detection. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition 303–312 (2021).

Fini, E. et al. A unified objective for novel class discovery. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision 9284–9292 (2021).

Rizve, M. N., Kardan, N. & Shah, M. Towards Realistic Semi-supervised Learning. in Computer Vision – ECCV 2022 (eds. Avidan, S., Brostow, G., Cissé, M., Farinella, G. M. & Hassner, T.) vol. 13691 437–455 (Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, 2022).

Grapa, A.-I., Blanc-Féraud, L., van Obberghen-Schilling, E. & Descombes, X. Optimal Transport vs Many-to-many assignment for Graph Matching. in GRETSI 2019-XXVIIème Colloque francophone de traitement du signal et des images (2019).

Liu, Y., Zhu, L., Yamada, M. & Yang, Y. Semantic correspondence as an optimal transport problem. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 4463–4472 (2020).

Vaswani, A. Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (2017).

Dalmaz, O., Yurt, M. & Çukur, T. ResViT: residual vision transformers for multimodal medical image synthesis. IEEE Trans. Med. Imag. 41, 2598–2614 (2022).

Menze, B. H. et al. The multimodal brain tumor image segmentation benchmark (BRATS). IEEE transactions on medical imaging 34, 1993–2024 (2014).

Nyholm, T. et al. MR and CT data with multiobserver delineations of organs in the pelvic area—Part of the Gold Atlas project. Medical Physics 45, 1295–1300 (2018).

Reichenberger, S., Bach, M., Skitschak, A. & Frede, H.-G. Mitigation strategies to reduce pesticide inputs into ground-and surface water and their effectiveness; a review. Sci. Total Environ. 384, 1–35 (2007).

Lei Ba, J., Kiros, J. R. & Hinton, G. E. Layer normalization. ArXiv e-prints arXiv-1607 (2016).

Misra, D. Mish: A self regularized non-monotonic activation function. arXiv preprint arXiv:1908.08681 (2019).

Dahl, G. E., Sainath, T. N. & Hinton, G. E. Improving deep neural networks for LVCSR using rectified linear units and dropout. in 2013 IEEE international conference on acoustics, speech and signal processing 8609–8613 (IEEE, 2013).

Dosovitskiy, A. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929 (2020).

Gutmann, M. & Hyvärinen, A. Noise-contrastive estimation: A new estimation principle for unnormalized statistical models. in Proceedings of the thirteenth international conference on artificial intelligence and statistics 297–304 (JMLR Workshop and Conference Proceedings, 2010).

Alaparthi, S. & Mishra, M. Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT): A sentiment analysis odyssey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2007.01127 (2020).

Oord, A. van den, Li, Y. & Vinyals, O. Representation learning with contrastive predictive coding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1807.03748 (2018).

Baid, U. et al. The RSNA-ASNR-MICCAI BraTS 2021 Benchmark on Brain Tumor Segmentation and Radiogenomic Classification. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/2107.02314 (2021).

Bakas, S. et al. The University of Pennsylvania glioblastoma (UPenn-GBM) cohort: Advanced MRI, clinical, genomics, & radiomics. Sci. Data 9, 453 (2022).

Miech, A., Laptev, I. & Sivic, J. Learnable pooling with Context Gating for video classification. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1706.06905 (2018).

Kingma, D. P. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980 (2014).

Zhou, Z., Sodha, V., Pang, J., Gotway, M. B. & Liang, J. Models genesis. Med. Image Anal. 67, 101840 (2021).

Zhou, H.-Y. et al. Comparing to Learn: Surpassing ImageNet Pretraining on Radiographs by Comparing Image Representations. in Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2020 (eds. Martel, A. L. et al.) vol. 12261 398–407 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2020).

Ghosal, P. et al. Brain tumor classification using ResNet-101 based squeeze and excitation deep neural network. in 2019 Second International Conference on Advanced Computational and Communication Paradigms (ICACCP) 1–6 (IEEE, 2019).

Patrick, M. et al. Support-set bottlenecks for video-text representation learning. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/2010.02824 (2021).

Wu, X., Yang, X., Li, Z., Liu, L. & Xia, Y. Multimodal brain tumor image segmentation based on DenseNet. Plos one 19, e0286125 (2024).

Gao, L. et al. MMGan: A multimodal MR brain tumor image segmentation method. Front. Human Neurosci. 17, 1275795 (2023).

Funding

Scientific and Technologial Innovation Programs of Higher Education Institutions in Shanxi,China,2023L493.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributions: C. was responsible for methodological innovation and overall architecture design. R.provided multimodal diagnostic insights and datasets from a pathological perspective. X. and F. were in charge of tumor diagnosis and consultation. W. contributed datasets and conducted preliminary data organization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, C., Zhang, X., Zhao, R. et al. Semantic structure preservation for accurate multi-modal glioma diagnosis. Sci Rep 15, 7185 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88458-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88458-7