Abstract

Besifovir dipivoxil maleate (BSV) is a novel antiviral agent widely used in South Korea for treating chronic hepatitis B (CHB). This study aimed to compare the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) following long-term use of BSV versus tenofovir alafenamide fumarate (TAF), utilizing large-scale national data. A total of 41,949 patients were analyzed, with propensity score matching (PSM) yielding 2,239 BSV and 6,717 TAF patients. The HCC incidence rate per 1,000 person-years was 1.8 for BSV versus 2.4 for TAF before matching (P = 0.057) and 1.6 versus 2.2 after matching (P = 0.284). Multivariate Cox regression identified age, male sex, antiviral duration, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score, and decompensated cirrhosis as significant risk factors for HCC, while antiviral type was not (HR 1.12, P = 0.413). Subgroup analyses showed no significant differences in HCC incidence between BSV and TAF in cirrhotic or non-cirrhotic patients. These findings suggest that BSV offers comparable efficacy to TAF in preventing HCC and is a promising option for CHB management. Longer-term studies with larger cohorts are necessary to confirm these results and assess the full impact of BSV on HCC prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) is a critical prognostic factor closely associated with mortality1,2. It is well established that current nucleos(t)ide analogues not only achieve virologic control but also significantly reduce the risk of HCC3. Entecavir and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) are recognized globally as first-line therapies for CHB. However, due to the need for long-term administration and concerns about toxicity, tenofovir alafenamide fumarate (TAF) was developed as a more favorable option with an improved safety profile, particularly regarding renal and bone toxicity4. Additionally, besifovir dipivoxil maleate (BSV), developed specifically in South Korea, has emerged as another promising alternative.

BSV has demonstrated comparable efficacy to existing first-line therapies regarding virologic response, serologic response, and laboratory improvement5. Moreover, BSV has shown favorable outcomes in managing drug-resistant hepatitis B virus strains, with a reduced risk of renal impairment and bone mineral density loss6,7.

Despite these promising results, the short duration of BSV administration and its limited availability in South Korea have contributed to a lack of long-term data on HCC incidence among BSV users. Although a comparative study between BSV and TAF regarding cirrhosis and HCC incidence has been conducted, it primarily focused on treatment response and was limited to only three institutions8. Therefore, this study aims to further evaluate the impact of BSV on HCC incidence through a large-scale analysis comparing it with TAF, utilizing comprehensive national data from South Korea.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 displays the baseline characteristics of the patients included in this study. The mean age was 51.1 ± 12.2 years, with 57.9% of the patients being male. No significant differences were observed in age, duration of antiviral medication, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score, or the presence of cirrhosis or decompensated cirrhosis. The median follow-up durations were 2.4 years and 2.3 years for each group, respectively, while the median follow-up duration for all patients was 2.3 years after PSM. After matching, the standardized mean differences for each variable ranged from 0.1 to 0.1, indicating that the characteristics of the two groups are comparable.

Incidence of HCC between BSV vs. TAF

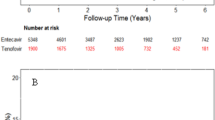

In the analysis of all patients, the incidence of HCC was slightly lower in the BSV group (2.62%) compared to the TAF group (3.19%) (P = 0.057). However, this gap narrowed after matching (2.37% vs. 2.71%; P = 0.284) (Fig. 1A, B). The IRR for the TAF group in all patients was not significantly different from that of the BSV group, both before and after matching (Before PSM: IRR 1.28, 95% CI 0.98–1.68, P = 0.065; After PSM: IRR 1.18, 95% CI 0.87–1.60, P = 0.295) (Table 2).

Kaplan-Meier plots for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) incidence by antiviral agents: (A) All patients before PSM. (B) All patients after PSM. (C) Non-cirrhotic patients before PSM. (D) Non-cirrhotic patients after PSM. (E) Cirrhotic patients before PSM. (F) Cirrhotic patients after PSM. HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, BSV besifovir dipivoxil maleate, TAF tenofovir alafenamide fumarate, PSM propensity score matching.

Subgroup analysis by the presence or absence of liver cirrhosis

These results were consistent across subgroup analyses conducted in both non-cirrhotic and cirrhotic patients. In non-cirrhotic patients, the incidence of HCC tended to be lower in the BSV group compared to the TAF group, both before and after matching, though the differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 1C, D; log-rank P = 0.100 and 0.219, respectively). The IRR for the TAF group was not significantly different from that of the BSV group, both before and after matching (Before PSM: 1.35, 95% CI 0.94–1.95, P = 0.107; After PSM: 1.30, 95% CI 0.85–1.98, P = 0.230) (Table 2).

Among cirrhotic patients, there was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of HCC between the BSV and TAF groups, both before and after matching (Fig. 1E, F; log-rank P = 0.385 and 0.819, respectively). Similarly, the IRR for the TAF group was not significantly different from that of the BSV group both before and after matching (Before PSM: 1.17, 95% CI 0.80–1.73, P = 0.417; After PSM: 1.05, 95% CI 0.68–1.64, P = 0.825) (Table 2).

Risk factor for HCC development

Cox regression analysis was conducted to identify risk factors for HCC occurrence. In the multivariate analysis, significant factors associated with HCC included age, male sex, duration of antiviral medication, CCI score, and decompensated cirrhosis. The type of antiviral medication was not a significant risk factor for HCC in either the univariate or multivariate analyses (P = 0.285 and P = 0.413, respectively) (Table 3). Cox regression analysis was also performed in the subgroup analyses for both non-cirrhotic and cirrhotic groups, and the difference in liver cancer incidence between BSV and TAF was not statistically significant (P = 0.203 and P = 0.778, respectively) (Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Table 3).

Discussion

BSV is an acyclic nucleotide phosphate developed in South Korea, functioning as a guanine monophosphate analogue. In a Phase IIb clinical trial comparing BSV with entecavir, BSV demonstrated comparable efficacy in terms of hepatitis B virus clearance, anti-Hepatitis B envelope (HBe) seroconversion, HBe antigen loss, and normalization of transaminases after 48 weeks of treatment5. These results were sustained in a Phase III extension study with a follow-up period of up to two years9. Additionally, a recent study confirmed BSV’s non-inferiority to TAF regarding virologic response8. Furthermore, BSV exhibited a lower incidence of common antiviral-related adverse effects, such as renal function decline and loss of bone mineral density (BMD), compared to TDF, and showed a similar safety profile to TAF6,10. Importantly, no instances of drug resistance or viral breakthrough were observed, and BSV demonstrated significant efficacy against drug-resistant HBV mutants7,11,12.

This study’s findings suggest that BSV has a comparable effect to TAF in preventing HCC incidence in both cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic CHB patients. Although the Kaplan-Meier analysis was not statistically significant (P = 0.284), the slightly lower incidence rate of HCC in the BSV group compared to the TAF group (1.6 vs. 2.2 per 1,000 person-years after matching) is noteworthy. This comparable effect of BSV to TAF in preventing HCC is particularly important given that TAF is widely used as a safer alternative to TDF with similar efficacy. The subgroup analysis, stratified by the presence of liver cirrhosis, further underscores the efficacy of BSV across diverse patient populations.

Tenofovir is recognized as a potent antiviral agent with therapeutic efficacy comparable to entecavir and superior effectiveness in reducing HCC risk13,14. The comparable performance of BSV to tenofovir may be attributed to its unique pharmacological properties, including its pivalic moiety structure, which depletes L-carnitine levels in the body. L-carnitine is crucial for transporting fatty acids into mitochondria during lipolysis, and its deficiency can lead to complications such as encephalopathy, cardiomyopathy, and rhabdomyolysis15. Consequently, supplementation with 660 mg of L-carnitine per day is recommended during BSV treatment. L-carnitine supplementation has been shown to alleviate muscle cramps, hyperammonemia, and hepatic encephalopathy, common complications in cirrhotic patients15. Additionally, it has been shown to lower transaminase levels, improve non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and hepatic steatosis, and reduce insulin resistance15,16,17.

Murata et al. recently found that interferon-λ3 levels increased in patients receiving nucleotide analogues but not in those receiving nucleoside analogues18. The nucleotide analogue nature of BSV, akin to TAF, rather than nucleoside analogues like entecavir or lamivudine, may partially explain its efficacy. Since interferon-λ3 possesses anti-carcinogenic properties, it is plausible that the cancer-suppressing effects of BSV are related to this mechanism. Furthermore, BSV was associated with a greater reduction in fibrosis stage compared to TDF and a similar reduction in covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) in a study19. Given that the majority of HCC develops through the progression of cirrhosis, these effects may help lower the incidence of HCC.

Previous studies have investigated the incidence of HCC in patients receiving BSV and TAF, including one study involving patients from three institutions8. However, it primarily focused on virologic response, and the sample size was limited to 200 patients. Another study assessed the impact of BSV on HCC incidence using the risk estimation for HCC in CHB (REACH-B) and the guide with age, gender, HBV DNA, core promotor mutation, and cirrhosis (GAG-HCC) models, but it was constrained by a small sample size of 188 patients and the use of predictive models rather than actual clinical data20.

The strength of the present study lies in its generalizability, as it targeted a broad and representative sample of the national population. Given that BSV is currently prescribed exclusively in South Korea, the study encompasses all available data for this drug. BSV and TAF were introduced in South Korea during the same period, with identical reimbursement criteria. Therefore, the characteristics of the patient populations prescribed these medications are likely to be very similar. Moreover, the use of PSM helps minimize potential confounding factors, enhancing the reliability of our comparison between BSV and TAF.

However, this study has several limitations. Importantly, due to the nature of the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA) claims database, critical information related to HCC development, such as hepatitis B virus serology, alcohol intake, and smoking status, was not collected and therefore could not be included in the Cox regression analysis. Additionally, the absence of mortality data precluded the implementation of competing risk analysis. Based on the fact that tenofovir, the prodrug of TAF, reduces the risk of HCC, with some evidence suggesting it may be more effective than entecavir in this regard, we conducted comparison between BSV and TAF. Nonetheless, only two studies to date have specifically examined the risk of HCC associated with TAF, and no comprehensive meta-analysis or systematic review has been conducted21,22. This limits the interpretability of the comparison and we are actively investigating this topic to address the existing knowledge gap. Although PSM was employed to mitigate the retrospective nature of the study design, which inherently introduces selection bias, complete control of confounding factors cannot be guaranteed. Notably, variables such as alcohol consumption were not included in the analysis. Furthermore, considering that the incidence of cirrhosis in CHB ranges from 12 to 20% over five years, and the progression from cirrhosis to HCC is approximately 6–15% during the same period, our study’s follow-up duration, while substantial, may still be insufficient to comprehensively evaluate HCC incidence.

Finally, this study utilized the CCI score, which is validated for one-year mortality prediction and shows relevance in long-term studies, including cancer populations. However, as highlighted in a recent literature23, the CCI has intrinsic limitations, including its design for short-term predictions and variability influenced by cancer stage and socioeconomic factors. These concerns may affect its applicability in predicting long-term outcomes. Further studies are needed to validate the use of CCI in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) research and refine its role in specific patient populations.

In conclusion, this study suggests that BSV is a promising drug for treating CHB, offering effects comparable to TAF in the prevention of HCC. As the global burden of CHB remains significant, it is crucial to have multiple effective and safe treatment options to optimize patient care. However, further long-term studies are necessary to determine its definitive impact. Given that BSV has been in use for a relatively short time and the observed trend toward a reduction in HCC incidence—despite the lack of statistical significance—longer-term studies with larger patient cohorts may yield more conclusive results.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

The study protocol received approval from the Institutional Review Board of Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital (SCHBC 2023-07-016-001, registered on September 23, 2023) and adhered to the ethical guidelines of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board of Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Data source

This study utilized data from the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service in South Korea. The country’s mandatory health insurance system provides extensive data covering approximately 98% of the population, with annual updates. BSV and TAF have been available in South Korea since November 2017, following their approval for reimbursement. Consequently, our study focused on treatment-naïve CHB patients who were first prescribed either BSV or TAF beginning in January 2018.

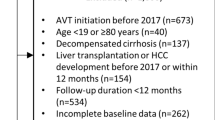

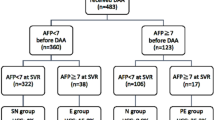

Patient selection

This study included all treatment-naïve CHB patients who began antiviral treatment for the first time between January 1, 2018 and December 31, 2022. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) administration of antiviral medications other than BSV or TAF (including combination therapy or drug switching) (n = 9,137); (2) diagnosis of HCC within 30 days of the initial antiviral prescription (n = 14,456); (3) an observation period of less than one year (n = 4); and (4) coinfection with hepatitis C virus or human immunodeficiency virus (n = 1,959). The patient selection process is shown in Fig. 2. After applying these criteria, the final cohort for analysis cohort included 41,949 patients, with 2,358 in the BSV group and 39,499 in the TAF group. To address selection bias between the groups, 1:3 propensity score matching (PSM) was implemented, yielding 2,239 patients in the BSV group and 6,717 in the TAF group.

Definition of CHB, antiviral treatment, and outcomes

CHB was defined using ICD-10 codes B18.0 and B18.1. The administration of antiviral medications was accurately tracked through a systematic approach utilizing the Korea Drug Code (KD code), with BSV corresponding to codes 665401ATB and TAF to 665301ATB. The primary outcome of the study was the incidence of HCC, identified through ICD-10 code C22.0, with all cases recorded after the initiation of antiviral treatment. Additionally, a subgroup analysis was conducted to examine how the incidence rates of liver cancer differed between patients using BSV and those using TAF, based on the presence or absence of underlying liver cirrhosis.

Statistical analysis

PSM was applied to reduce confounding between the BSV and TAF groups, with matching criteria including age, gender, presence of cirrhosis, and comorbidities assessed via the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). Detailed CCI variables are provided in Supplementary Table 1. PSM was executed at a 1:3 ratio between the BSV and TAF groups. Survival probabilities were estimated using Kaplan-Meier curves, and differences between the groups were tested for statistical significance using the log-rank test. To identify factors associated with the development of HCC, adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using a multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model. This model accounted for potential confounders, including age, gender, presence of cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis, and CCI score, diabetes. When the proportional hazards assumption was violated, alternative models, such as the Poisson model, were considered. Descriptive statistics were employed to analyze the variables, with frequencies and percentages reported for categorical data. The Chi-square test was used for categorical variables, while Student’s t-test assessed relationships between continuous variables. A 90-day washout period was established before 2018, and person-years (PY) and incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were calculated from the date of the first antiviral prescription to the onset of HCC. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Two-sided tests were performed, with statistical significance established at P < 0.05.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kim, D. Y. Changing etiology and epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: Asia and worldwide. J. Liver Cancer. 24, 62–70. https://doi.org/10.17998/jlc.2024.03.13 (2024).

Korean Liver Cancer, A., National, C. & Center, K. KLCA-NCC Korea practice guidelines for the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Liver Cancer 23, 1–120. https://doi.org/10.17998/jlc.2022.11.07 (2023).

Korean Association for the Study of. The, L. KASL clinical practice guidelines for management of chronic hepatitis B. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 28, 276–331. https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2022.0084 (2022).

Hsu, Y. C., Tseng, C. H. & Kao, J. H. Safety considerations for withdrawal of nucleos(t)ide analogues in patients with chronic hepatitis B: first, do no harm. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 29, 869–890. https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2022.0420 (2023).

Lai, C. L. et al. Phase IIb multicentred randomised trial of besifovir (LB80380) versus entecavir in Asian patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gut 63, 996–1004. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305138 (2014).

Ahn, S. H. et al. Efficacy and safety of besifovir dipivoxil maleate compared with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 17, 1850–1859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2018.11.001 (2019).

Won, J. et al. Susceptibility of drug resistant hepatitis B virus mutants to besifovir. Biomedicines 10, 1637. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10071637 (2022).

Kim, T. H. et al. Noninferiority outcomes of besifovir compared to tenofovir alafenamide in treatment-naïve patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gut Liver. 18, 305–315. https://doi.org/10.5009/gnl220390 (2024).

Yim, H. J. et al. Besifovir dipivoxil maleate 144-week treatment of chronic hepatitis B: an open-label extensional study of a phase 3 trial. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 115, 1217–1225. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000000605 (2020).

Jung, C. Y. et al. Similar risk of kidney function decline between tenofovir alafenamide and besifovir dipivoxil maleate in chronic hepatitis B. Liver Int. 42, 2408–2417. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.15388 (2022).

Yuen, M. F. et al. Two-year treatment outcome of chronic hepatitis B infection treated with besifovir vs. entecavir: results from a multicentre study. J. Hepatol. 62, 526–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2014.10.026 (2015).

Song, D. S. et al. Continuing besifovir dipivoxil maleate versus switching from tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for treatment of chronic hepatitis B: results of 192-week phase 3 trial. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 27, 346–359. https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2020.0307 (2021).

Choi, J. et al. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients treated with entecavir vs tenofovir for chronic hepatitis B: a Korean Nationwide Cohort Study. JAMA Oncol. 5, 30–36. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4070 (2019).

Chen, M. B. et al. Comparative efficacy of tenofovir and entecavir in nucleos(t)ide analogue-naive chronic hepatitis B: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 14, e0224773. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224773 (2019).

Hanai, T. et al. Usefulness of carnitine supplementation for the complications of liver cirrhosis. Nutrients 12, 915. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12071915 (2020).

Musso, G., Gambino, R., Cassader, M. & Pagano, G. A meta-analysis of randomized trials for the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 52, 79–104. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.23623 (2010).

Li, N. & Zhao, H. Role of Carnitine in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and other related diseases: an update. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 8, 689042. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.689042 (2021).

Murata, K. & Mizokami, M. Possible biological mechanisms of entecavir versus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate on reducing the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 38, 683–691. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.16178 (2023).

Yim, H. J. et al. Besifovir therapy improves hepatic histology and reduces covalently closed circular DNA in chronic hepatitis B patients. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 37, 378–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.15710 (2022).

Yim, H. J. et al. Reduced risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B receiving long-term besifovir therapy. Cancers (Basel). 16, 887. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16050887 (2024).

Lim, Y. S. et al. Tenofovir alafenamide and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate reduce incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B. JHEP Rep. 5, 100847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2023.100847 (2023).

Lee, H. W. et al. Effect of tenofovir alafenamide vs. tenofovir disoproxil fumarate on hepatocellular carcinoma risk in chronic hepatitis B. J. Viral Hepat. 28, 1570–1578. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvh.13601 (2021).

Drosdowsky, A. & Gough, K. The Charlson Comorbidity Index: problems with use in epidemiological research. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 148, 174–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.03.022 (2022).

Funding

This study was supported by Soonchunhyang University Research Fund (2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hyuk Kim: Investigation and Writing—original draft. Jae-Young Kim: Formal analysis and Writing—review and editing. Yoon E Shin: Investigation and Writing—review and editing. Hye-Jin Yoo: Investigation and Writing—review and editing. Jeong-Ju Yoo: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision and Writing—review and editing. Sang Gyune Kim: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision and Writing—review and editing. Young-Seok Kim: Supervision and Writing—review and editing

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, H., Kim, JY., Shin, Y.E. et al. Comparison of hepatocellular carcinoma incidence after long-term treatment with besifovir vs. tenofovir AF. Sci Rep 15, 5637 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89325-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89325-1