Abstract

We demonstrate a novel injection-locking effect in oscillators, which is obtained in both the time and frequency domains. The “temporal-locked” oscillator generates an ultra-low phase noise continuous-wave (CW) signal, accompanied by an ordered train of short \(2\pi\) phase pulses with precise timing, where both signals are phase-locked to an external sinusoidal source. Remarkably, even when the cavity delay drifts, the period of the temporal-locked pulses remains constant. Furthermore, the instantaneous phase and the timing of the minimum and maximum amplitudes within part of the pulse remain approximately constant. These unexpected results stem from the nonlinear effect of strong injection on the waveform of the phase pulses. In particular, this effect leads to the self-adaptation of the instantaneous frequency to delay variations, thereby preserving the periodicity of the pulses. We theoretically show that a simple and general setup can accurately model the pulse propagation within the cavity. We experimentally demonstrate the effect in an optoelectronic oscillator (OEO). The pulse timing inherits the stability of the external CW source. The combination of an ultra-low phase noise CW signal with precisely timed pulses is important for various applications that require accurate measurements in both the time and frequency domains.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Synchronization between oscillators has been extensively studied in almost all fields of science and engineering1. The modern study of limit-cycle oscillation was initiated by Poincaré in his lectures given in 1908 at the École Supérieure des Postes et Télégraphes and by Andronov2. Subsequently, mathematical models for the synchronization between two coupled oscillators have been developed by Appleton3 and Van der Pol4. One of the important synchronization effects, called forced injection-locking, is obtained when an external source is injected into an oscillator4. The injected signal can cause various dynamical effects, such as quasi-periodic oscillation5,6, and even chaotic behavior1. In particular, under certain conditions, the oscillator can generate a continuous-wave (CW) signal that is phase-locked to a sinusoidal injected signal5. In this case, the injection-locked oscillator is forced to oscillate at the injected frequency rather than at its stand-alone resonance frequency, and the detuning between the resonance frequency of the oscillator and the frequency of the injected signal determines its phase. The model for injection-locking in oscillators with nonlinearity was first given by Van der Pol4. A simple dynamic equation for the phase of such an oscillator was given and solved in a steady state condition by Adler5, assuming that the injected signal is weak, and it was later extended to a strong injection7. The results of the models indicate that phase-locking is obtained when the injected frequency is inside a narrow region, called locking region (LR), around the oscillator resonance frequency. Injection-locking has been studied in different fields of engineering, such as electronics6,8 and photonics (see for example9 and a recent review10). It is used in various applications in the field of RF systems, such as in frequency dividers11. In communication systems, the effect is used to retrieve the phase in electronic12,13 and optical receivers14.

Injection-locking can also be obtained in delay-line or often-called multimode oscillators, where the cavity length is significantly longer than the oscillation wavelength. Such oscillators can potentially oscillate in a large number of cavity modes, and the injection of an external CW signal can be used to determine the oscillating mode15. In previous work, we have demonstrated that under certain conditions an injection-locked delay-line oscillator can generate a CW-like signal with short-ordered \(2\pi\) phase jumps, which we refer to as phase pulses16. The pulses had a repetition period that was equal to the roundtrip cavity delay, and the CW part between the short pulses was phase-locked to the injected signal. The phase pulses were generated due to a unique mode-locking effect. A CW oscillation experiences a low gain due to the amplifier saturation. On the other hand, phase pulses can experience a higher effective gain since their instantaneous phase rapidly jumps by \(2 \pi\) with respect to the injected signal. Therefore, in part of the pulse, the injected signal increases the pulse amplitude. In different parts of the pulse, the injected signal decreases the oscillator amplitude. However, this decrease is suppressed by the increase in the gain of the saturated amplifier. Moreover, the cavity filter response to the short pulses further increases their amplitude. The Generation of phase jumps (also called phase kinks) was theoretically predicted by solving the complex Ginzburg-Landau equation (CGLE) with an injection term17,18. The effect was experimentally demonstrated and theoretically studied in semiconductor lasers19,20, quantum cascade lasers21. The generation of the phase pulses in lasers is based on the Kerr or the “Kerr-like” effect, where the refractive index is changed due to the variation in the atomic population in the different energy levels. The effect was also demonstrated in OEOs16, where the magnitude of the Kerr-like effect is negligible. In this case, the pulses were generated due to the strong injected signal, which caused a large deformation in the pulses as a function of their instantaneous phase.

In this manuscript, we demonstrate a novel injection-locking effect in pulsed oscillators, which we refer to as “temporal-locking” (TL), or alternatively, “time-locking”. The effect, which is obtained for phase pulses, enables locking the instantaneous phase along the short pulses to an external sinusoidal source. When the cavity delay drifts due to changes in environmental conditions, the repetition period of the pulses does not change. Moreover, in this case, the instantaneous phase in a specific part of the pulse almost does not vary, such that the maxima and minima amplitudes in this part maintain their timing with respect to the injected signal. This result is in striking contrast with the classical injection-locking phenomenon5,7 in CW oscillators, where the relative phase between the oscillator and the injected signals must largely change to compensate for the delay changes. The repetition period of TL pulses inherits the long-term stability of the external sinusoidal signal, such that the overlapping Allan deviation of the pulse period becomes similar to that of the external source, although the frequency of this source can be orders of magnitude larger than the pulse repetition rate. By using an ultra-low phase noise oscillator, such as an OEO, and a stabilized sinusoidal external source, it is possible to simultaneously generate an ultra-low phase noise CW signal and pulses with a low jitter and a high long-term stability. Thus, the TL effect extends the classical locking effects from the frequency to the time domain.

The temporal-locking effect is caused by the injection of a strong signal. While the accumulated phase jump along the short pulses is equal to \(2\pi\), the exact time dependence of the instantaneous phase is controlled by the strong injected signal. When the cavity delay drifts, the instantaneous frequency varies, such that the roundtrip propagation time of the pulses is maintained. We show that a simple and general setup can be used to accurately model the propagation of TL pulses along the cavity, such that the model results are in good quantitative agreement with our measurements. The simple setup can be implemented in various fields and oscillators such as lasers or micro-cavities, which generate optical combs. We also give an analytical analysis in the time domain to the change in the oscillator signal after adding the injected signal, and the results extend those obtained by the classical approaches5,7. The TL effect was experimentally demonstrated in an ultra-wideband OEO with a strong injection of a high-frequency sinusoidal signal. The effect enables us to dramatically improve the time stability of the TL pulses, in comparison with that obtained for non-TL pulses, reported in our previous work16. The measured overlapping Allan deviation of TL pulses was about \(0.4 \cdot 10^{-11}\) over 100 sec, which is similar to that of the external CW source. The phase noise of the CW part of the waveform was similar to that of a CW injection-locked OEO, and at some frequency offsets, it was about 25 dB lower than that of the low-noise external source.

The generation of pulses with a highly stable repetition rate, combined with an ultra-low-phase noise CW signal, offers significant advantages. TL oscillators enable performing high-precision measurements in both the time and frequency domains. Therefore, it can be used to develop novel measurement systems and to improve the performance of light detection and ranging (LIDAR) and RADAR systems, which require an accurate measurement of both the distance and the velocity of targets. The accurate timing of the pulses is important to measure the distance, while the low-phase noise of the CW part is important to measure the Doppler shift. These advantages are also important for optical time domain reflectometers (OTDR) and optical frequency domain reflectometers (OFDR). The ultra-broad bandwidth and the fast frequency change (chirp) along the short pulse are important for Photonics Radars22,23. The optical and the RF spectrum of the phase pulses contain a very dense frequency comb (FC), which is locked to the injected frequency, and therefore it can be used for various measurements based on frequency combs, such as high-resolution spectroscopy24, which also often requires a very long time measurements. TL oscillators also offer a simple and accurate solution for applications that require synchronization between clocks or measurement systems, which are located in different sites, such as in Bistatic Radars, optical or electronic coherent receivers, and distributed processing.

Temporal-locking mode of operation (TLMO)

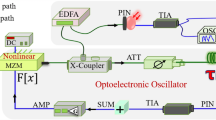

(a) Schematic description of a temporal-locked (TL) oscillator. The injection is modeled by an adder \((\Sigma )\), which sums the amplifier output a(t) and the injected signal \(a_{inj}(t)\). The cavity contains a long delay \(\tau\), an effective bandpass filter (BPF), an amplifier with a fast saturation, and a fast nonlinear element \(f_{NL}\), modeled by a nonlinear function, \(f_{NL}[s(t)]\) that is schematically shown in the inset of Fig. 1(a), where the black dot denotes the chosen operating point. This setup can be used to accurately model the pulse propagation in our experimental setup. (b) A plot of the oscillator waveform at the amplifier output a(t), where the CW part of the waveform and the phase pulse are denoted by black and blue curves, respectively. (c) A zoom view around the pulse (marked by a blue curve) with an inset, which shows the instantaneous phase calculated using the Hilbert transform. The pulse can be identified by the change in its period. (d) Normalized instantaneous frequency \(\hat{\omega }(t)/\omega _{inj}\) along the pulse, which was extracted for three cavity delays that correspond to our measurement results, shown in Fig. 2, where the blue curve corresponds to the lowest delay and the red and the green curves were obtained when the delay was increased by 1.2 ps and 2.2 ps, respectively. The figure shows that the instantaneous frequency \(\hat{\omega }(t)\) of the TL pulses is self-adapted to changes in the cavity delay.

A schematic description of a temporal-locked (TL) oscillator is shown in Fig. 1(a). Although this setup is general and simple, it can be used to accurately model the propagation of TL pulses inside an OEO, which was used to experimentally demonstrate the effect, as described in section 4. The oscillator cavity contains a bandpass filter (BPF), a fast saturable amplifier, a long delay \(\tau\), and a nonlinear element, described by a function \(f_{NL}\left[ s(t)\right]\), which is shown in the inset of the figure, where \(a_{in}(t)\) is the input signal to the element and \(\psi _0\) is a parameter that controls its operating point. The injection is described by an adder, such that \(s(t)=a(t)+a_{inj}(t)\), where s(t) is the summed signal, \(a_{inj}(t)\) is an injected sinusoidal signal at a frequency \(\omega _{inj}\), and a(t) is the signal at the amplifier output. The cavity delay \(\tau\) is significantly longer than the injection signal period \(\tau \gg T_{inj}=2 \pi /\omega _{inj}\), where \(\omega _{inj}\) is the injected frequency. Figure 1(b) shows the waveform of the oscillator signal, where the black and the blue colors denote the CW-like part of the waveform and the phase pulse, respectively. Figure 1(c) gives a zoom around the pulse with an inset that shows its instantaneous phase, \(\hat{\phi }(t)\), which was calculated by using the Hilbert transform25. The phase jump along the pulse causes a rapid change in the frequency, which can be observed by the variation of the time periodicity. To use realistic waveforms, the results shown in the figure correspond to our measurement results described in Sec. 4, where the ratio between the amplitudes of the injected and the oscillator signals was about 0.15, resulting in a power injection ratio of \(-16.5\) dB. The pulse duration is only about 4 cycles of the injected signal, while the pulse repetition period, which is equal to the cavity delay, is orders of magnitude longer. The CW-like signal between the pulses is phase-locked to the external source, as obtained in the classical models for injection-locking5,7.

To understand the essence of the temporal-locking effect, we present here some measurement results, which are shown in Fig. 2(a). A detailed description of the experiment, which was implemented in an OEO, will be provided later in Sec. 4. Our theoretical analysis indicates that the propagation of the TL pulses in the OEO can be accurately modeled by the simple and general setup shown in Fig. 1(a). Figure 2(a) shows the TL pulses, obtained for three different cavity delays, where the blue and the green curves correspond to the shortest and the longest delay. Figure 2(b) gives a zoom-in view on the CW part of the waveform, which is marked by a blue box in Fig.2(a). The large effect of the delay change on the phase of the CW part can be observed in the figure, and it can be modeled by using classical approaches for analyzing CW injection-locking5,7. Figure 2(c) gives a zoom-in view of part of the pulse, which is marked by a pink box in Fig.2(a), with a further zoom near the minimum amplitude in the temporal-locked region that is marked by an orange ellipse. Contrary to the large phase change in the CW part of the waveform, Fig. 2(c) shows that the delay variation did not significantly affect the phase in the TL part of the pulse. Consequently, the timing for the minimum or maximum amplitudes within that region remains approximately constant. This unexpected result is caused due to the self-adaptation of the pulse waveform to the delay change. In particular, the instantaneous frequency, defined as the time derivative of the instantaneous pulse phase, strongly depends on the cavity delay as can be seen in Fig. 1(d). In the following section, we show how this frequency change enables maintaining a constant roundtrip time even when the cavity delay changes.

Waveforms of the TL pulse, measured for three cavity delays. The delay difference between the first (blue curve) and the last measurement (green curve) was about 2.2 ps. (a) A Zoom-in view around a phase pulse, where the pulse is obtained between about \(-0.1\) ns to 0.3 ns. (b) A zoom-in view on a cycle in the CW part of the waveform, which is highlighted by a blue box in Fig.2(a). (c) A zoom-in view on part of the phase pulse, which is denoted by a pink box in Fig.2(a), with a closer zoom-in view around the time when the minimum amplitude is obtained in the temporal-locked (TL) part of the pulse. The change in the delay causes a large phase shift of the CW part of the waveform, while the extrema points in the TL part of the pulse almost do not change their timing. The measurements were performed by a real-time oscilloscope with a sampling rate of 80 GS/sec.

Analysis of the temporal-locking (TL) mode of operation (TLMO)

We start the analysis of the TLMO by calculating in the time domain the change in the signal after adding a strong injected signal. This calculation enables analyzing short pulses, despite their rapid phase change. We assume that the injected signal is a sinusoidal wave: \(a_{inj}(t)=A_{inj}\cos \left[ \phi _{inj}(t)\right]\), where \(\phi _{inj}(t)=\omega _{inj}t+\Delta \phi _0\), \(A_{inj}\) and \(\omega _{inj}\) are the amplitude and the frequency of the injected signal, and \(\Delta \phi _0\) is a constant phase. We model the signal at the amplifier output as:

where the time t changes on the shortest timescale of less than a period of the injected wave \(T_{inj}\), T changes on a longer timescale, on the order of \(T_{inj}\), and A(T) and \(\alpha (T,t)\) are the signal amplitude and phase. To obtain a unique representation of the very short pulse, we require that the pulse amplitude A(T) will depend only on the slow timescale T and it does not change significantly along a cycle of the waveform, while the instantaneous phase can change on a shorter timescale, t. We define the instantaneous frequency of the pulse as \(\hat{\omega }(T,t) = d\alpha (T,t)/dt\) and the relative phase between the oscillator and the injected signals as \(\Delta \phi (t) \equiv \alpha (T,t)- \phi _{inj}(t)\). A longer timescale \(T_r\), on the order of the roundtrip time, should be added to Eq. 1 to study transient effects. However, since we do not analyze those effects in this manuscript, we omit this notation.

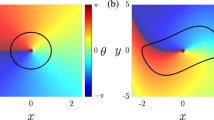

(a) Changes in the oscillator signal due to the addition of the strong injected signal \(a_{inj}(t)\) (green curve), where the summed signal, s(t) (red color) is equal to \(s(t)=a(t) +a_{inj}(t)\) and a(t) (blue curve) is the amplifier output. The waveform is split into cycles \(p=0..5\), where \(p=0\) denotes the last cycle of the CW part of the waveform before the pulse starts. The figure indicates that, as a function of the cycle number p, the injection changes the maximum amplitude of the pulse s(t) and shifts the times when it is obtained by \(\Delta t_p\), as given in Eq. 5. Since the time shift is proportional to the time derivative of the injected signal, \(\Delta t_{p=2}>0\) in cycle #2 and \(\Delta t_{p=5}<0\) in cycle #5, as denoted by the orange arrows. The calculation shown in the figure corresponds to the experimental results described in Sec. 4. (b) Calculated (red curve) and measured (blue curve) instantaneous frequency with respect to the frequency of the signal (green curve) before adding the injected signal. The measured results were extracted from the pulse waveform by using the Hilbert transform, and the calculated result was obtained using Eq. 6.

In phase pulses, the relative phase, \(\Delta \phi (t)\), rapidly changes along the pulse. Figure 3 shows the oscillator signal a(t) (blue curve), the injected signal \(a_{inj}(t)\) (green curve), and the calculated summed signal \(s(t)=a_{inj}(t)+a(t)\) (red curve). The injection ratio, which is defined as the ratio between the maximum amplitudes of the injected and the oscillator signals at the output of the adder, shown in Fig. 1(a) was equal to \(r_{inj}=1/6.5\), in accordance with our measurements. To model the injection effect along the pulse, we split the time into intervals \([k\tau ,\;(k+1)\tau ]\), where k is the roundtrip number and \(\tau\) is the cavity delay. We further split the time in a single roundtrip to cycles and denote each cycle by an integer number p, as shown in Fig. 3. We focus our analytical study on the changes in the extrema points of the pulse amplitude (minima or maxima) after adding the injected signal. Those points are sufficient to accurately describe the injection effect since the bandwidth of the amplifier in our experiments is slightly below an octave span and since the injection effect is small, as shown in Fig. 3, since \(r_{inj}=1/6.5\). We derive below the equations for the maxima of the waveform. The same equations apply to the minima of the waveform, although the numerical values for the minima points may differ slightly due to the rapid variation of the signal phase along the pulse. We define by \(t_p\) and \(\tilde{t}_p\) the times when the maximum amplitude is obtained in the p-th cycle before and after the addition of the injected signal and by \(\Delta t_p\equiv \tilde{t}_p-t_p\) as the time shift between the maxima. The injection also changes the maximum amplitude from \(A_p\equiv a(t_p)\) to \(S_p\equiv s(\tilde{t}_p)\). Using the signal presentation in Eq. 1, the phase at \(t_p\) is equal to \(\alpha (t_p)=2p\pi\). We define the phase around this maximum and the corresponding instantaneous frequency by \(\alpha _p(t)\equiv \alpha (t)-2p\pi\) and \(\hat{\omega }_p (t) = d{\alpha _p}(t)/dt\), respectively. The injected signal in the p-cycle can be written as \(a_{inj}(t-t_p) = A_{inj}\cos \left[ \omega _{inj}(t-t_p)-\Delta \phi _p \right]\), where \(\Delta {\phi _p}=\Delta \phi (t_p)\) is the relative phase at \(t_p\). At the time \(\tilde{t}_p\), the amplitude of the summed signal, s(t), reaches its maximum value, and therefore the time derivative \(s'(\tilde{t}_p)=0\). Using the connection, \(s(t)=a(t)+a_{inj}(t)\) we obtain:

Since the argument of the \(\sin ^{-1}\) function must be in the region \([-1,\;1]\), we can obtain a necessary condition for a steady state operation: \({\left| {{{\hat{\omega }}_p}\left( {\Delta {t_p}} \right) \sin \left[ {{\alpha _p}\left( {\Delta {t_p}} \right) } \right] } \right| \le {A_{inj}}{\omega _{inj}}/{A_p}}\). The equation also indicates that after adding the injected signal, the oscillator amplitude can potentially change within the region \(\left[ A_p-A_{inj},\; A_p-A_{inj}\right]\). When both the injected \(a_{inj}(\tilde{t}_p)\), and the oscillator \(a(\tilde{t}_p)\) signals have the same sign, the injection increases the maximum amplitude of the summed signal such that \(S_p>A_p\). However, when the two signal amplitudes have opposite signs, the injection decreases the amplitude \(S_p\).

In continuous wave (CW) oscillators, variations in environmental conditions change the cavity delay, which in turn affects the resonance frequency of the oscillator. To obtain a steady state operation the relative phase between the oscillator and the injected signals, \(\Delta \phi\), must be adjusted, such that the addition of the injected signal will compensate the changes in the accumulated cavity phase. The dependence of the relative phase on the cavity delay can be calculated in the frequency domain, based on the approaches in the classical models for injection-locking of CW oscillators5,7 and its extension to delay-line or multimode oscillators26. The same equation can be obtained from Eq. 2, which was developed in the time domain. The delay offset from the zero detuning case is mathematically defined by splitting the cavity delay, \(\tau\), into \(\tau =\tau _0+\Delta \tau\), where \(|\Delta \tau | < T_{inj}/2 \ll \tau _0\), \(\tau _0=2m\pi /\omega _{inj}\), and m is an integer number. For CW signals, we omit the index p and require that at a steady state condition the delay offset will be exactly compensated by the time shift, \(\Delta t\), such that \(\Delta t=-\Delta \tau\). According to Eq. 2 the necessary condition for the locking becomes: \(|\Delta \tau |\le (1/\omega _{inj})\sin ^{-1}\left( r_{inj} \right)\), where the injection ratio \(r_{inj}=A_{inj}/A\) and A is the oscillator amplitude. The obtained phase shift is equal to:

This result accurately describes the measured phase of the CW part of the waveform in our experiments, described in Sec. 4, since the CW part contained a large number of about 7000 cycles.

Equations 2 and 3 can also be used to analyze the short pulses in the time domain, and it gives a nonlinear connection between the time shift \(\Delta t_p\), the pulse parameters \((A_p,\;\alpha _p, \;\hat{\omega }_p)\), and the relative phase \(\Delta \phi _p\). In our experiments, the time shift \(\Delta t_p\) is small, as can also be observed in Fig. 3, such that \(\hat{\omega }_p \Delta t_p \ll 1\). In this case, Eq. 2 can be simplified by using a first-order expansion of the pulse phase: \({\alpha _p}\left( {\Delta {t_p}} \right) = {{\hat{\omega }}_p}\Delta t + O{\left( \Delta {t_p} \right) ^2}\), such that:

and the amplitude becomes \(S_p\simeq A_p-A_{inj}\cos \left( {\Delta {\phi _p}}\right)\). The same result can also be obtained for approximately sinusoidal signals by using a second-order approximation of a(t) and \(a_{inj}(t)\), as shown in Sec. I in the supplementary material. We note that the approximation we used to obtain Eq. 5 does not depend on the relative phase, \(\Delta \phi _p\), as required to analyze the phase pulses. The denominator of the equation is always positive, since the injection ratio \(r_{inj}<1\) and \(\hat{\omega }_p \ge \omega _{inj}\). The numerator of the equation, which is also equal to the time derivative of the injected signal \(-a'_{inj}(t_p)\), is proportional to \(\sin (\Delta \phi _p)\). Since the relative phase, \(\Delta \phi (t)\), changes by \(2\pi\) along the short pulses, the sign of the time shift \(\Delta t_p\) varies as a function of p, such that the maximum of a(t) is shifted toward the nearest maximum of the injected signal. The change in the sign of \(\Delta t_p\) is demonstrated in Fig. 3. In cycle #2, the phase \(\Delta \phi _{p=2}\simeq 35^\circ\) and hence \(S_{p=2}>A_{p=2}\) and \(\Delta t_{p=2}>0\), as denoted by the orange arrow. In cycle #5, \(\Delta \phi _{p=5}\simeq 308^\circ\) and therefore \(\Delta t_{p=5}<0\).

The strong injection also changes the instantaneous frequency of the pulse. To study this effect, we calculate the instantaneous frequency of the summed signal using a first-order approximation. The p-th maximum of the summed signal is obtained at time \(t_p+\Delta t_p\). We define the relative time \({{\bar{T}}_p} = t - \left( {{t_p} + \Delta {t_p}} \right)\) and approximate the summed signal around \({{\bar{T}}_p} =0\) by \(s\left( {{{\bar{T}}_p}} \right) = {S_p}\cos \left( {{\Omega _p}{{\bar{T}}_p}} \right)\), where \(\Omega _p\) is the instantaneous frequency at \({\bar{T}}_p\gtrapprox 0\) and \({\Omega _p}{{\bar{T}}_p} \ll 1\). Using connections \(s\left( {{{\bar{T}}_p}} \right) = {A_p}\cos \left( {{{\hat{\omega }}_p}{{\bar{T}}_p}} \right) + {A_{inj}}\cos \left( {{\omega _{inj}}{{\bar{T}}_p} - \Delta {\phi _p}} \right)\) and the approximation \({{\hat{\omega }}_p}\Delta {t_p} \ll 1\), the phase of the summed signal \(\Omega _p {{\bar{T}}_p}\) for \(0<{{\bar{T}}_p}\ll \Delta t_p\) can be calculated up to the first order in \(\Delta t_p\), and the instantaneous frequency obtained is equal to:

Figure 3(b) shows a comparison between the instantaneous frequency of the summed signal that was calculated by using Eq. 6 (red curve) and the corresponding frequency, which was extracted from the measured signal waveform using the Hilbert transform (blue curve). The green curve shows the extracted frequency \(\hat{\omega }_p\) before adding the injected, which was used in the calculation. The injection ratio \(r_{inj}(p)\equiv A_p/A_{inj}\) depends on the cycle number p. We neglected this effect in our calculations and used an average injection ratio of 1/6, in comparison with the ratio of 1/6.5 obtained in the CW part of the waveform. Since in cycle #4, \(r_{inj}(p=4)\) is slightly lower than 6, as can be seen in Fig. 3(a), the calculated frequency at this cycle is slightly lower than obtained from measurements. The denominator of Eq. 6, which is equal to the amplitude of the summed signal \(S_p\), is the dominant term for the parameters, which correspond to our experiment. At the first part of the pulse, the relative phase \(\Delta \phi _p\) increases toward \(\pi\), and hence the injection enhances the instantaneous frequency. The highest enhancement is obtained when \(\Delta \phi _p=\pi\), and after that when \(\phi _p\gtrsim \pi\) the injection triggers the decrease of the frequency as shown in Fig. 1(d).

The injection stabilizes the temporal-locking of the pulses due to its effect on the instantaneous frequency \(\Omega _p\), given in Eq. 6 and on the time shift \(\Delta t_p\), given in Eq. 5. For example, we consider the pulse waveform shown in Fig. 3(a), where the relative phase in the CW part of the pulse is equal to \(\Delta \phi _{CW}\simeq 14^{\circ }\). At the beginning of the pulse, the phase, \(\Delta \phi (t)\), starts increasing and becomes close to \(\pi\) approximately near the time when the minimum amplitude in cycle #3 is obtained. After that time, the instantaneous frequency starts returning back toward the injected frequency, and at the end of the pulse, the relative phase becomes \(\Delta \phi _{CW}+2\pi\). The injection forms negative feedback that stabilizes the pulse. For example, in cycle #2, the relative phase equals \(\Delta \phi _{p=2} \approx 35^{\circ }\). A temporal perturbation, which slightly increases the time \(t_{p=2}\), will decrease the relative phase, \(\Delta \phi _{p=2}\). Therefore, according to Eqs. 5 and 6, the frequency will be enhanced, and the time shift, \(\Delta t_{p=2}>0\) will decrease in comparison with their steady-state values. These changes will decrease \(t_{p=2}\), which will eventually lead to the suppression of the initial perturbation. Similar negative feedback is obtained when \(t_{p=2}\) is slightly decreased.

The nonlinear element (NLE) in the cavity was modeled by a simple transfer function \({f_{NL}}\left[ a_{in}(t) \right]\), where \(a_{in}(t)\) is the input signal that is equal according to Fig. 1(a) to s(t). The function is shown schematically in the inset of Fig. 1(a) and is equal to: \({f_{NL}}\left[ a_{in}(t) \right] = {\sin ^2}\left[ { ka_{in}(t) + \psi _0 } \right]\), where \(k>0\) is a constant, and \(\psi _0\) is a controllable phase, which determines the operating point. The same effective transfer function is used in the Ikeda model27 or the Ikeda-like models for studying optical oscillators, where the temporal refractive index is changed due to the Kerr effect or due to the Kerr-like effect in amplifiers, in which the refractive index depends on the population inversion of the atomic states. The control phase, \(\psi _0\), is adjusted by controlling the cavity length. In our experimental setup, described in Sec. 4, the NLE was a Mach-Zehender modulator (MZM), such that \(\psi _0\) is set by the MZM bias voltage and \(k=\pi /2V_{\pi }\), where \(V_\pi\) is the modulator \(\pi\) voltage. The bias phase \(\psi _0\), which corresponds to our experiments, was \(\psi _0 \lesssim \pi /6\) as marked by a solid dot in the inset of Fig. 1(a). The NLE causes an effective saturation effect for strong signals, where \(\psi \equiv \pi /4<kS_p+\psi _0 \lesssim \pi /2\). Another saturation effect is caused by the amplifier, as described in Sec. III in the supplementary material, where the amplifier was modeled by using the Saleh equation28. The calculated results for the OEO, used in our experiments, indicate that the dominant saturation effect was caused by the MZM. The maximum differential gain \({f'}_{NL}(\psi ) \equiv d{f_{NL}}/d{\psi }=\sin (2\psi )\) is obtained for \(\psi (t)= \pi /4\) and therefore the NLE enhances amplitude changes in weak signals. Consequently, when \(kS_p+\psi _0<\pi /2\), the NLE increases the instantaneous frequency as the input amplitude \(S_p\) is increased. The combination of this effect and the cavity filter helps obtain a stable propagation of the pulses. Since the input signal is strong, the NLE causes a large deformation in the output waveform, as can be seen in Fig. S2 in the supplementary material. This deformation is further enhanced when the input amplitude is negative due to the choice of the bias phase of the NLE, \(\psi _0<\pi /4\). In the frequency domain, this deformation causes the generation of new harmonics around the frequencies \(m\omega _{inj}\), where \(m=0,2,3..\). However, as shown in Sec. III in the supplementary material, the cavity filter suppresses the new harmonics, and after a roundtrip, the signal returns to its initial waveform.

In our experiments, the cavity delay was changed by controlling the environmental temperature. This change affected the relative phase \(\phi (t)\), and therefore the pulse parameters including its instantaneous frequency and amplitude are varied as can be seen in the experimental and the calculated results described below, which are shown in Figs. 1(d) and 2, and in Fig. S5 in the supplementary material. However, the change in the timing of the extrema points along the pulse is significantly smaller than obtained in the CW part of the waveform due to the negative feedback described above. Since the periodicity time of the pulses almost does not depend on the cavity delay, the group delay (GD) of the pulses must be self-adapted when the delay changes. The GD at a frequency \(\omega\) is equal to \(\tau _g(\omega )=-d \angle s(\omega ) /d\omega\), where \(\angle s(\omega )\) is the phase of the summed signal spectrum, \(s(\omega )=\mathscr {F} \{s(t) \}\), where \(\mathscr {F}\) denotes a Fourier transform. This spectrum can be roughly estimated from the time-dependent instantaneous frequency \(\hat{\omega }_p\) shown in Figs. 1(d) and 3(b). Despite its short duration, the pulse can be roughly regarded as an asymptotic signal29, due to the very large frequency change along the pulse (chirp). For asymptotic signals, the spectrum and the GD can be estimated from the instantaneous frequency \(\Omega (t)\) by solving the equation \(\omega =\Omega [\hat{\tau }_g(\omega )]\). The BFP, which models the amplifier frequency response, has a bandwidth between 6-11.5 GHz, and its maximum gain was obtained at approximately 8.3 GHz.

Figure 1(d) shows that the maximum instantaneous frequency of the pulse decreases from about 10.3 GHz to 9.3 GHz when the delay was increased. The corresponding decrease in the summed signal was from about 11.4 GHz to 10 GHz. Since the maximum frequency of the sum signal is close to the upper limit of the amplifier bandwidth, the amplifier affects the GD of the pulses. Besides changing the pulse bandwidth, the injection affects the GD of the pulse since it changes the dependence of the instantaneous frequency \(\Omega (t)\) on time, as shown in Fig. 1(d). The increase in the frequency along the pulse is slower than its decrease. Figure 3(b) shows that the injection varies this time asymmetry in the theoretical as well as in the experimental results. This asymmetry is further enhanced by the memory of the cavity BPF due to its short impulse response function. Consequently, according to the analytic signal approximation, the GD of the pulses is decreased when the cavity delay is increased.

In the following paragraph and in Sec. VI in the supplementary material, we show that the simple model shown in Fig. 1(a) is sufficient to model the propagation of the TL pulses, such that good quantitative agreement is obtained between theory and experiments.

Experimental results and its comparison to a simple cavity model

We have demonstrated the TL effect in a broadband OEO, which was temporal-locked to a high-frequency standard CW synthesizer. The OEO signal was measured in the RF domain, and therefore we were able to measure directly the pulse waveform up to a timescale, which corresponds to the carrier frequency. Such a measurement can not be performed in the optical domain due to the high carrier frequency of optical signals. A detailed description of the experimental setup is given in Sec. II in the supplementary material. We describe below some important results and show that the simple and general setup, shown in Fig. 1, can be used to accurately model the propagation of the pulses in the OEO cavity and its dependence on the cavity delay.

OEOs generate ultra-low phase noise RF signals due to their very long cavity length, which is obtained by transmitting the RF signal through a long fiber. In such oscillators, the RF signal modulates the intensity of an optical wave by using a Mach-Zehender modulator (MZM). The modulated wave propagates through a long fiber, is then converted back to an RF signal by a photodetector, and is amplified by a wideband RF amplifier. The injected signal is added to the amplifier output by using an RF directional coupler, and the summed signal is fed back into the RF port of the MZM to close the cavity loop. To obtain short pulses, no filters were added to the cavity and the bandwidth was determined by the amplifier frequency response, which had full width at half maximum (FWHM) between 6-11.5 GHz. The repetition rate and the period of the pulses were about \(f_{rep} = 900\) kHz and 1.11 \(\mu\)s, respectively, which corresponds to the delay \(\tau\) of about 230 m length fiber that was used in our experiments. In the simple setup, described in Fig. 1, the NL element, the cavity delay, the filter, and the adder correspond to the MZM, the propagation delay in the long fiber, the amplifier bandwidth, and the directional coupler, respectively. Five RF isolators were spread in the cavity to prevent back-reflections.

The setup used to obtain the TLMO is the same as used in our previous work16, where we have demonstrated the generation of short \(2 \pi\) phase pulses, which were non-temporal-locked (NTL) to the external source. The jitter and the time-stability of those pulses were significantly worse than those obtained for TL pulses. NTL pulses could also be easily identified by the dependence of their period on environmental conditions, while the period of the TL pulses remained constant. Moreover, in TL pulses, the frequency ratio, \(k=f_{inj}/f_{rep}\), between the injected frequency and the pulse repetition rate, measured using a frequency counter as described in Sec. IV in the supplementary material, remained very close to an integer with a very high accuracy of about \(10^{-10}\), indicating that the group and phase velocities of the pulses were approximately the same. NTL pulses could be obtained over a wide range of injected signal parameters, and for these pulses, the frequency ratio, k, significantly deviated from an integer. TLMO was obtained when the injected signal parameters were within a certain operating region. This region could be systematically found, as described in Sec. IV in the supplementary material, since the frequency ratio k of NTL pulses depends on the injected signal frequency and power due to cavity dispersion and the effect of strong injection on the timing of these non-time-stabilized pulses. The TLMO operating region had to be found only once and there was no need for adjustments to the parameters of the injected signal according to environmental conditions. In particular, to obtain the TL pulses, we had to significantly increase the injected signal power by approximately 10 dB compared to that used in our previous work16, resulting in an amplitude injection ratio \(r_{inj}\) of about 0.15, which corresponds to a power injection ratio of \(-16.5\) dB. The measured width of the power operating region was about 2 dB. The operating frequency was within several frequency regions, inside the amplifier bandwidth between \(6.3-11\) GHz. We chose to work with an injection frequency of about 6.3 GHz, since the shortest pulses were generated and since initialization of the TL pulses was highly robust. The operating frequency can be controlled by tailoring the cavity dispersion, and we verified that when the cavity length was varied, the exact frequency changed as expected.

The phase pulses are not self-started, since amplitude perturbations are highly suppressed due to the deep gain saturation caused by the amplifier and the NLE. Therefore, to initiate the pulses, there is a need for an initialization procedure. This procedure, described in Sec. IV in the supplementary material, is simpler than used in our previous work16 and it does not require any “trial-and-error” process. The phase noise of the TL OEO was measured using a Signal Source Analyzer (SSA) and is shown in Fig. S6 of the supplementary material. The noise spectrum is similar to that measured when the initialization process was not performed, and the injection-locked OEO generated only a CW signal (CW OEO). The main difference between the CW and TL modes of operation is the addition of a frequency comb with narrow-bandwidth lines in the spectrum of the TL OEO, which can be observed at about the frequencies of the spurious modes (spurs) of the CW OEO, corresponding to the cavity modes. At a low-frequency offset below about 6 kHz, the injected signal improved the phase noise of the TL OEO compared to that measured for the CW OEO operated with a very low power injection ratio of about \(-40\) dB, since the external source stabilizes the carrier frequency of the OEO. However, at a frequency offset between 6 and 600 kHz, the phase noise of the TL OEO becomes worse than that of a CW OEO operated at a very low power injection ratio. The maximum difference in noise was about 10 dB at a frequency offset of approximately 400 kHz. This increase in the phase noise of the TL OEO is caused by the relatively strong injection of the external signal, which has significantly higher phase noise at those frequencies compared to the internal noise sources of the OEO. Consequently, at a frequency offset greater than about 600 kHz, the phase noise of the external source decreases and does not significantly affect the noise of the TL OEO.

We also demonstrated the TLMO in an OEO with a 1200 m length fiber instead of the 230 m fiber, used in the OEO described in this manuscript. The increase in fiber length changed the pulse repetition period from 1.1 \(\mu\)sec to about 5.84 \(\mu\)sec. The measured phase noise of the long-cavity OEO, which is shown in Fig. S7 in the supplementary material, indicates that the phase noise at a frequency offset of about 10 kHz decreased by about 10.1 dB compared to that obtained in the 230 m length cavity. However, the expected theoretical improvement in a CW stand-alone OEO is 14.4 dB26,30, which is better than what was achieved in the TL OEO due to the large injected noise of the external source used in our experiments.

Our system was built from components that were not isolated from its environment, and we did not add any external feedback. A delay drift due to variations in the environmental temperature caused a large change in the phase of the CW part of the waveform, as shown in Fig. 2(b). This phase change is in accordance with the classical theories for injection-locked5,7 since the delay drift changes the resonance frequency of the oscillator. When the drift is sufficiently large, the oscillation stops since the injected frequency becomes outside the locking region (LR) of the oscillator. This limitation exists for any injection-locked OEO that generates a CW signal, and it was easily eliminated by adding simple feedback. Despite this limitation, the TL pulses were maintained over a minimum duration of 20 minutes and up to more than 7 hours. Therefore, the TLMO is inherently robust and to obtain an unlimited operation time there is only a need to add a very slow and simple external feedback to correct drifts. Fast perturbations in the TL oscillator are self-suppressed due to the inherent negative feedback formed by the injection, which has a response time on the order of the carrier period. Such feedback can be implemented by monitoring the phase of the CW part of the waveform with respect to the external source and controlling the cavity delay by adding a phase shifter. TL OEOs are also expected to have a low sensitivity to mechanical vibrations, since their setup is similar to that used in OEOs. In comb lasers, a drift in the cavity delay is corrected by adding a complex feedback that controls the cavity length31,32. Optical comb generation in microresonators can sometimes be obtained over a long time without external feedback due to a self-thermal-sensitive drift, induced by the pump power33 and due to the coexistence of two stable solutions34.

Overlapping Allan deviation \(\sigma\) of the TL pulse period (blue curve), which is compared to that of the injected CW signal (red curve). The two measurements were performed sequentially due to the limitation of our frequency counter. Although the injected frequency was 6.3 GHz and the pulse repetition rate was about 899.4 kHz, the Allan deviation of both signals is similar. To obtain a stable trigger to the counter, the phase pulses were converted into amplitude pulses by multiplying the oscillator and the injected signal in an RF mixer. Therefore, the measurement accuracy is limited by the external source.

To measure the long-time stability of the TL pulses, we used a frequency counter (Keysight 53230A-010). However, since the amplitude change along the phase pulses was too small to accurately trigger the counter, we had to convert the large phase change along the pulses into an amplitude change by adding an external mixer, which multiplied (mixed) the OEO output with part of the injected wave, as shown in Sec. II in the supplementary material. Therefore, the accuracy of such measurements was limited by the external source. The TLMO could be obtained when the injected power was within a fixed region with a width of about 2 dB. When the injected power was set slightly outside this region, the oscillator continued to generate phase pulses; However, in this case, the pulses were not TL (NTL), and their period fluctuated and drifted. The change between TL and NTL pulses could be identified by monitoring the pulse period when the injected signal power was changed over time, using a frequency counter with a gate window of 200 ms, as described in Sec. V and illustrated in Fig. S3 in the supplementary material. The period fluctuation of NTL pulses was about \(\pm 0.5\) ps, and the repetition rate was typically changed by about 1 Hz over 1000 sec. In the TLMO, the period fluctuation was dramatically reduced to only about \(\pm 400\) attoseconds, which is 3 orders of magnitude lower than obtained for NTL pulses and the average period was maintained despite the delay drift. The transition between the two operation modes due to the change in the injected power was abrupt and occurred over a timescale, which is shorter than the gate window of the counter (200 ms). This sharp transition implies that TL and the NTL pulses correspond to two different operation modes of the system. The dramatic change in the short-time jitter between TL and NTL pulses could be also directly observed in a real-time oscilloscope.

Figure 4 shows the overlapping Allan deviation of the TL pulses (blue curve), which is compared to that of the external CW source (ANRITSU MG3694C/3) (red curve). The injected frequency was about 6.3 GHz while the repetition rate of the pulses was about 897.7 kHz. The measurements were performed over 1200 sec with a gate time of 1 sec. Due to the limitation of our counter, we could not simultaneously measure both the injected signal and the pulses, and therefore the two measurements were performed one after the other. The results, shown in Fig. 4, indicate that the Overlapping Allan Deviation of the TL pulses is similar to that of the external source, despite the large difference between their periods. For NTL pulses, the measured Allan deviation rapidly grew as a function of the window duration, \(\tau\), and for \(\tau =10\) sec it became about \(6\cdot 10^{-8}\), which is about 4 orders of magnitude higher than that obtained for the TL pulses. We have also measured the overlapping Allan deviation for a TL OEO with a long cavity fiber of approximately 1200 m, instead of the 230 m fiber used to obtain the results shown in Fig. 4. Although the repetition period of the pulses increased from about 1.11 to 5.84 \(\mu\)sec, the overlapping Allan deviation of the TL pulses remained similar, as shown in Fig. S8 in the supplementary material. These measurements are also similar to those of the external source, and did not change significantly when the injected power was varied within the 2 dB power range where the TLMO was obtained. These findings indicate that our measurement results are limited by the noise of the external source. As explained above, this source was also used in our measurement system for the Allan deviation of the TL pulses to convert the large phase change along the pulse into a strong amplitude signal. Therefore, we can only conclude that the use of an external CW source with better stability may improve the Allan deviation of the TL pulses compared to that shown in Fig. 4. The negative feedback, which locks the timing of TL pulses to the external source as described in Sec. 3, has a response time significantly longer than the roundtrip time due to the high effective Q-factor of the cavity, as obtained in CW injection-locked oscillators26. Noise and drift from the external source, which change on a longer time scale, will be transferred to the OEO signal, as described in more detail at the end of Sec. VIII in the supplementary material. However, noise that changes on a shorter time scale might be suppressed, allowing the OEO to have lower timing noise than that of the external source.

To gain a deeper understanding of the TLMO and its dependence on the cavity delay, we simultaneously measured important signals in the cavity as a function of the cavity delay by using a real-time sampling oscilloscope with four input channels, which were synchronically sampled at a rate of 80 GS/s per channel. The measured signals were the injected and the amplifier output signals, the output of the coupler, which adds the injected signal, and the optical signal at the input of the photodetector. The last signal, which corresponds to the output of the MZM after passing through the fiber, was measured by adding another wideband photoreceiver with a bandwidth between about \(1-28\) GHz. The signals were simultaneously measured over a time window of 1.2 \(\mu\)s, which is slightly longer than the cavity delay. This measurement was repeated every about 2 minutes over 22 minutes, and the total number of measurements was 12. To enhance the delay drift between measurements, we decreased the room temperature along the experiment by about \(1^{0}\) C by controlling the temperature of the air-conditioner. The trigger of the oscilloscope, which is common for all of its 4 channels, was set according to the maximum amplitude of the wideband signal at the output of the additional photoreceiver. However, since the timing of this signal changes as a function of the cavity delay, we had to synchronize between the 12 different measurements. This synchronization was accurately performed by using the measurement of the external source, which was simultaneously sampled with the other 3 tapped signals. Since this signal does not depend on cavity drift, it was used to accurately synchronize the different measurements. We have verified that the 4 input channels of the oscilloscope are simultaneously sampled by performing a large number of measurements when the same signal was supplied to the 4 inputs. The measured relative jitter between the 4 channels was less than the sampling period of 12.5 ps.

Figure 2 shows the effect of the cavity delay drift on the TL pulses measured at the amplifier output, where the colors denote the different measurements. The figure shows 3 typical results, chosen out of the 12 measurements, \(j=1..12\), where the blue, green, and red curves correspond to measurement \(j=1\), 7, and 12, respectively. Figure 2(a) shows a zoom around the pulse, where the pulse is obtained between about \(-0.2\) ns to 0.4 ns. Figure 2(b) shows a zoom-in view on the CW part of the pulse, which is marked by a blue box in Fig.2(a). The figure indicates that the delay drift causes a large change in the phase of the CW part of the signal, as given in Eq. 4. Figure 2(c) shows a zoom-in view on part of the pulse, marked by a pink box in Fig. 2(a) with a further zoom around a minimum of the pulse amplitude, marked by an orange circle, which is located in the TL part of the pulse. The sampling period of the oscilloscope was \(T_s=12.5\) ps, which corresponds to an angle change of \(\omega _{inj}T_s=28.3^\circ\) in the injected signal phase. However, assuming that most of the signal spectrum is within the bandwidth of the oscilloscope (26 GHz), the time resolution of the reconstructed signal can be increased behind the sampling period according to the Sampling Theorem13. The actual resolution was estimated to be about 1.2 ps or \(2.8^\circ\) by measuring the maximal phase fluctuation in the CW part of the pulse, where the signal phase noise is very small, as shown in Fig. S6 in the supplementary material. The phase change in the CW part of the waveform between the first and the last measurement was about 17.6 ps, which corresponds to \(40^\circ\). However, despite this large change, the variation in the time of the minimum amplitude in TL cycle, \(\hat{t}_{p=4}\), was significantly smaller. The change in \(\hat{t}_{p=4}\) between the first (blue curve) and the other measurements was equal to or lower than 1.2 ps for 10 out of the 12 measurements, and 1.87 ps for measurements #6 and #8.

Comparison between the calculated signal after it propagated 5 times in the cavity (red curve) and the measured signal (blue curve), where the green curve corresponds to the injected signal. The two plots correspond to measurements #5 and #12, in the drift experiment, and the relative phase between the oscillator and the injected signals at the CW part of the waveform were equal to \(-7.1^\circ\) and \(-33.2^\circ\), respectively. The propagation in the cavity was modeled according to the general and simple setup, shown in Fig. 1(a).

As noted before, a detailed comprehensive theoretical study of the complete OEO setup, shown in Fig. S1 in the supplementary material, is behind the scope of this manuscript. However, we show in this manuscript that the pulse propagation in the cavity can be accurately modeled using the simple setup, shown in Fig. 1(a). In the case of a Lorentzian BPF, this setup can be also analyzed by an Ikeda-like delay equation35, with an additional term, caused by the injection. In our simulation, the signal was calculated after each cavity element as described in Sec. VI of the supplementary material. Since the bandwidth of the cavity signals spans almost a full octave, we had to simulate the components that were added to perform the measurements. The measured data, which was used in the calculation of the pulse propagation, was a set of 12 measurements, \((j=1..12)\), that were taken along a drift experiment, described above. Each measurement corresponds to a different cavity delay and the tapped amplifier output a(t) for measurements #1, #7, and #12 is shown in Fig. 2. The cavity delay, which depends on the measurement number j, was extracted by using the measurement of the summed signal, s(t). However, the pulse waveform of the signals a(t) and s(t), as well as the delays of these signals, have a complex nonlinear dependence on the cavity delay due to the strong injection. This delay strongly affects the complex pulse waveform, and therefore it should be calculated with sufficient accuracy to extract the small delay change between measurements, which was on the order of less than 1 ps. We solved together a set of 12 equations: \(s_j(t-\tau _{s,j})=C_{inj} \cdot a_{inj}(t)+C_a \cdot a_j(t-\tau _{a,j})\), where \(j=1..12\) is the measurement number, \(C_a,\;C_{inj},\; \tau _{s,j},\;\tau _{a,j}\) are 26 unknown parameters, and \(a_j(t)\) and \(s_j(t)\) are the amplifier and the summed signal waveforms that correspond to the j-th measurement. Since we want to study if the simple cavity model, shown in Fig. 1(a), can be used to accurately analyze the roundtrip pulse propagation, we used in the calculation of the cavity parameters only the CW part of the signals. The 12 equations were simultaneously solved under the constraints that the total error is minimized and that the errors are uniformly distributed between all the measurements. The obtained injection ratio was equal to \(r_{inj}\simeq 1/6.5\), which is in good agreement with our estimation from measurements that was equal to 0.15. After the cavity parameters were found, we calculated the propagation of the pulse over 5 cavity roundtrips. Figure 5 shows the injected signal (green curve) and a comparison between the measured (blue curve) and the calculated signal (red curve) that correspond to measurements #5 and #12. A similar fitting was obtained for all the 12 measurements. The figure indicates that a good quantitative agreement is obtained between the theoretical and experimental results. A similar good quantitative agreement is also obtained for the detected signal at the output of the MZM, as shown in Fig. S4 in the supplementary material. Therefore, we can conclude that the general and the simple setup, shown in 1(a), can be used to accurately model the roundtrip propagation of TL pulses. Some small amplitude discrepancies can be observed for the extrema points of cycles #3 and #4, which are attributed to the simple model we used for the BPF.

The model results indicate that the minimum cavity delay is obtained for measurement #1, and it increased by about 1.2 and 2.2 ps in measurements #7, and #12, respectively. This delay causes the variation of the corresponding phase of the CW part by \(20.4^{\circ }\) and \(40.2^{\circ }\), respectively. The corresponding measured results were \(\Delta \psi =20.1^{\circ }\) and \(39.8^{\circ }\). The maximum phase shift, \(40.2^{\circ }\), corresponds to a shift in the time of the maxima in the CW part of the waveform by \(\Delta t\simeq -17.7\) ps. The time of the maximum in the TL part of the pulse, which is obtained in cycle #4, was shifted by less than 3.1 ps in comparison to 2.5 ps obtained in the experiment. However, the change in the measured time when the minimum amplitude in cycle #4 was obtained was lower than 1.87 and it was less or equal to 1.2 ps for 10 out of the 12 measurements. The accuracy of the measured result was limited by the sampling period, which is significantly longer than the time shift. The theoretical model was limited since we did not take into account the precise frequency response of the amplifier. Therefore, further theoretical and experimental study is needed, to find the exact dependence of the TL part of the pulse on the cavity delay.

Conclusions

In this manuscript, we demonstrated a novel injection-locking effect in pulsed oscillators, which we refer to as “temporal-locking” (TL), or alternatively, “time-locking”. The effect broadens the concept of injection-locking into the combined time and frequency domains. The TL oscillator, which was studied, generates a CW signal with an ordered train of short \(2\pi\) phase pulses, which are both phase-locked to a high-frequency sinusoidal source. The TL pulses maintain a constant repetition period even when the cavity delay drifts. In a specific part of the pulse, the instantaneous phase does not significantly depend on the cavity delay, and therefore in this region, the timing when the maximum and the minimum amplitudes are obtained is nearly unchanged.

The temporal-locking effect is based on injecting a strong signal to the oscillator. The injection effect varies along the pulse due to the fast change in the relative phase between the injected and the oscillator signals. The induced changes in the instantaneous frequency of the pulse affect its cavity propagation time, such that the pulse repetition period almost does not change when the cavity delay drifts. The TL oscillator cavity was accurately modeled by a simple and general setup, such that a good quantitative agreement was obtained between theory and experiments. We also give analytical results, calculated in the time domain, that extends the results that are calculated in the frequency domain using classical approaches for injection-locking5,7. The simple and general model used in our theoretical study does not rely on any unique feature that can be obtained only in OEOs. Therefore, the TL effect can be potentially demonstrated in various types of oscillators, such as semiconductor lasers20, quantum cascade lasers21, and in miniature devices such as microring lasers36 and micro-cavities, which generate a comb signal37. Further theoretical and experimental work is required to study the short-term and long-term noise of TL oscillators and to find their stability and its locking region.

The temporal-locking effect was experimentally demonstrated in an optoelectronic oscillator (OEO), which generated optical and RF pulses. The measured Allan deviation of the pulse period was similar to that of the injected source, although the injected frequency was orders of magnitude greater than the pulse repetition rate. The use of an external source with better stability may improve the performance of the TL oscillator. The inherent negative feedback that stabilizes TL oscillators is obtained on a fast timescale, on the order of the carrier period, and hence the oscillation is expected to be robust. Furthermore, the setup of the TL OEO is similar to that used in injection-locked OEOs, suggesting that the oscillator will likely have a low sensitivity to vibrations. In our experiments, the oscillation duration was limited by the locking region bandwidth since the resonance frequency of the OEO drifted over time due to the temperature effect on the OEO’s long fiber. This limitation, which also exists in injection-locked CW OEOs, can be mitigated by adding slow and simple external feedback, which is based on measuring the phase of the CW part of the waveform.

The TL effect enables to simultaneously generate a low-phase noise CW-like signal, which is injection-locked to the external source, combined with pulses that have a high time stability. Therefore, TL oscillators offer important advantages for systems that require precise measurements in both the time and the frequency domain, such as RADARS, light detection and ranging (LIDAR), and optical time domain reflectometers (OTDR) systems. The fast and wideband frequency change (chirp) along the pulse is important for Photonics Radars22,23. It is also important to synchronize between measurements that are performed in different locations.

Data Availability

The experimental and theoretical results described in this manuscript and in the supplementary material are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Pikovsky, A., Rosenblum, M. & Kurths, J. Synchronization: a universal concept in nonlinear science (American Association of Physics Teachers, 2002).

Andronov, A. A. Les cycles limites de poincaré et la théorie des oscillations auto-entretenues. Acad. Sci. 189, 559–561 (1929).

Appleton, E. V. Automatic synchronization of triode oscillators. In Proc. Cambridge Phil. Soc. 21, 231 (1922).

Van Der Pol, B. Forced oscillations in a circuit with non-linear resistance (reception with reactive triode). The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science 3, 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/14786440108564176 (1927).

Adler, R. A study of locking phenomena in oscillators. Proc. IRE 34, 351–357. https://doi.org/10.1109/JRPROC.1946.229930 (1946).

Razavi, B. A study of injection locking and pulling in oscillators. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 39, 1415–1424. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSSC.2004.831608 (2004).

Paciorek, L. Injection locking of oscillators. Proc. IEEE 53, 1723–1727. https://doi.org/10.1109/PROC.1965.4345 (1965).

Kurokawa, K. Injection locking of microwave solid-state oscillators. Proc. IEEE 61, 1386–1410. https://doi.org/10.1109/PROC.1973.9293 (1973).

Hora, H. Anthony e. siegman, “lasers” oxford university press, university science books, oxford, england, 1283 pages. Laser and Particle Beams5, 553-553, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0263034600003050 (1987).

Liu, Z. & Slavík, R. Optical injection locking: From principle to applications. J. Lightwave Technol. 38, 43–59 (2020).

Rategh, H. R., Samavati, H. & Lee, T. H. A cmos frequency synthesizer with an injection-locked frequency divider for a 5-ghz wireless lan receiver. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 35, 780–787 (2000).

Woodyard, J. Application of the autosynchronized oscillator to frequency demodulation. Proceedings of the Institute of Radio Engineers 25, 612–619. https://doi.org/10.1109/JRPROC.1937.228107 (1937).

Proakis, J. Digital Communications 4th Edition. (McGraw-Hill Science, 2002).

Braun, R.-P., Grosskopf, G., Rohde, D. & Schmidt, F. Low-phase-noise millimeter-wave generation at 64 ghz and data transmission using optical sideband injection locking. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 10, 728–730 (1998).

Fleyer, M., Sherman, A., Horowitz, M. & Namer, M. Wideband-frequency tunable optoelectronic oscillator based on injection locking to an electronic oscillator. Opt. Lett. 41, 1993–1996. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.41.001993 (2016).

Diakonov, A. & Horowitz, M. Generation of ultra-low jitter radio frequency phase pulses by a phase-locked oscillator. Opt. Lett. 46, 5047–5050 (2021).

Malomed, B. A. & Nepomnyashchy, A. A. Kinks and solitons in the generalized Ginzburg-Landau equation. Phys. Rev. A 42, 6009–6014. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.42.6009 (1990).

Chaté, H., Pikovsky, A. & Rudzick, O. Forcing oscillatory media: Phase kinks vs. synchronization. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 131, 17–30 (1999).

Gabrin, B., Javaloyes, J., Tissoni, G. & Barland, S. Topological solitons as addressable phase bits in a driven laser. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6915 (2015).

Barland, S. et al. Temporal localized structures in optical resonators. Adv. Phys. X 2, 496–517. https://doi.org/10.1080/23746149.2017.1321501 (2017).

Prati, F. et al. Soliton dynamics of ring quantum cascade lasers with injected signal. Nanophotonics 10, 195–207. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2020-0409 (2021).

Zhang, F., Qingshui, G. & Shilong, P. Photonics-based real-time ultra-high-range-resolution radar with broadband signal generation and processing. Sci. Rep. 7, 13848. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14306-y (2017).

Liu, Y., Zhang, Z., Burla, M. & Eggleton, B. J. 11-ghz-bandwidth photonic radar using mhz electronics. Laser Photon. Rev. 16, 2100549. https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.202100549 (2022).

Udem, T. & Hänsch, R. H. Optical frequency metrology. Nature 416, 233–237 (2002).

King, F. W. Hilbert Transforms, vol. 2 of Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications (Cambridge University Press, 2009).

Fleyer, M. & Horowitz, M. Phase measurement by using a forced delay-line oscillator and its application for an acoustic fiber sensor. Opt. Express 26, 9107–9133. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.26.009107 (2018).

Ikeda, K. Multiple-valued stationary state and its instability of the transmitted light by a ring cavity system. Opt. Commun. 30, 257–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-4018(79)90090-7 (1979).

Saleh, A. Frequency-independent and frequency-dependent nonlinear models of twt amplifiers. IEEE Trans. Commun. 29, 1715–1720. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCOM.1981.1094911 (1981).

Boashash, B. Estimating and interpreting the instantaneous frequency of a signal. I. Fundamentals. Proc. IEEE 80, 520–538. https://doi.org/10.1109/5.135376 (1992).

Yao, X. & Maleki, L. Optoelectronic oscillator for photonic systems. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 32, 1141–1149. https://doi.org/10.1109/3.517013 (1996).

Jones, D. J. et al. Carrier-envelope phase control of femtosecond mode-locked lasers and direct optical frequency synthesis. Science 288, 635–639. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.288.5466.635 (2000).

Cundiff, S. T. & Ye, J. Colloquium: Femtosecond optical frequency combs. Rev. Mod. Phys. 75, 325–342. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.75.325 (2003).

Carmon, T., Yang, L. & Vahala, K. J. Dynamical thermal behavior and thermal self-stability of microcavities. Opt. Express 12, 4742–4750. https://doi.org/10.1364/OPEX.12.004742 (2004).

Herr, T. et al. Temporal solitons in optical microresonators. Nat. Photonics 8, 145–152 (2014).

Larger, L. Complexity in electro-optic delay dynamics: modelling, design and applications. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 371, 20120464. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2012.0464 (2013).

McCall, S. L., Levi, A. F. J., Slusher, R. E., Pearton, S. J. & Logan, R. A. Whispering-gallery mode microdisk lasers. Applied Physics Letters60, 289–291, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.106688 (1992). https://pubs.aip.org/aip/apl/article-pdf/60/3/289/7483644/289_1_online.pdf.

Kippenberg, T. J., Holzwarth, R. & Diddams, S. A. Microresonator-based optical frequency combs. Science 332, 555–559. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1193968 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dmitry Alekhin for his help in performing part of the experiments described in the supplementary material.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. Diakonov initialized the experimental study; V. Smulakovsky conducted the experiments; M. Horowitz analyzed the experimental results, performed the theoretical work, and wrote the manuscript; A. Katzenelson helped to perform the experiments and contributed to the numerical simulation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Smulakovsky, V., Diakonov, A., Katzenlson, A. et al. Temporal locking of pulses in injection locked oscillators. Sci Rep 15, 5602 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89828-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89828-x