Abstract

This paper studied the prescribed-time platooning control problem for connected autonomous vehicles subject to unknown dynamics and stochastic actuator faults. Precisely, to compensate for the effect of unknown dynamic behaviour, the radial basis function-based adaptive observer design was developed that incorporates into the closed-loop control system, which enhances the robustness of the proposed control algorithm. In addition, physical actuator fault factors are also taken into account, which are denoted in terms of a Bernoulli-distributed stochastic variable. Lyapunov stability theory and the stochastic analysis method is used to derive the stability of the addressed control system. Finally, a numerical example with detailed simulation results is provided to illustrate the effectiveness of the proposed control design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid advancement of autonomous driving technology, platooning control of connected autonomous vehicles (CAVs) has become an increasingly significant aspect of intelligent transportation systems. Specifically, a typical CAV network consists of one leader vehicle and several follower vehicles. The platooning controller design for CAV is intended to maintain a predetermined distance between each pair of vehicles by matching the velocity of the leader vehicle1,2,3. Based this concept, the implementation of platoon management necessitates an effective distributed cooperative driving control mechanism to synchronize the movement of vehicles in the platoon, ensuring the formation and preservation of optimal following distances. This approach heavily depends on the sensing capabilities integrated into each vehicle, as well as the degree of communication between vehicles and the automation of internal vehicle operations.4,5. The platooning technology offers several key advantages, including improved driving safety, enhanced traffic efficiency, and reduced energy consumption6,7.

Due to the advantages of platooning CAVs, various control policies based on inter-vehicle spacing strategies have been proposed, such as the constant spacing8, constant headway, and varying headway policies. Initially, typical platooning control algorithms were based on string stability analysis9. Recently, there has been significant interest in using optimal time-based stability techniques, including finite-time stability10, fixed-time stability11, and prescribed-time stability12, with prescribed-time stability being the most advanced for ensuring fast and reliable convergence within predetermined time bounds, regardless of initial conditions13.

Actuator and sensor faults are inevitable in platooning vehicles due to prolonged use, aging, and environmental conditions. Actuator faults result in incorrect inputs, causing improper vehicle responses and posing safety risks.14 In light of the challenges posed by actuator faults, incorporating advanced fault-tolerant control strategies becomes essential. Recent studies, such as the online fault-tolerant control approach based on the policy iteration algorithm for nonlinear time-delay systems, demonstrate the potential of iterative learning to address system uncertainties in real-time scenarios15. Similarly, adaptive dynamic programming-based fault-tolerant control for nonlinear time-delay systems highlights the benefits of adaptive learning frameworks in designing robust controllers for complex systems16. These approaches provide valuable insights into managing fault dynamics in nonlinear systems with time delays and offer a foundation for extending these techniques to the stochastic platooning framework proposed in this work17. The neural network-adaptive estimator approach integrates the learning capabilities of neural networks with adaptive estimation techniques to address the challenges of measurement accuracy and prediction reliability in dynamic systems18,19. This approach leverages neural networks ability to model complex, non-linear relationships within data while dynamically adjusting estimations based on real-time observations and environmental changes20. The neural network-adaptive estimator approach provides a robust framework to address the aforementioned challenges in platooning control. The neural network acts as an adaptive estimator, learning and predicting the dynamics of the vehicles in real time. It can adapt its parameters based on the observed behavior of the vehicles, effectively compensating for unknown factors influencing performance21. This approach integrates fault detection mechanisms that identify actuator faults by analyzing discrepancies between expected and actual vehicle behavior. The neural network can adjust control strategies dynamically to account for identified faults, thereby enhancing stability and safety22,23. While several advanced platoon control methods exist, few address actuator fault effects during controller design24. Moreover, most fault-tolerant platooning systems consider faults within a deterministic framework, which may not reflect real-time conditions25,26. To address this, the paper introduces a stochastic framework for fault description and adapts the controller to mitigate fault effects27.

Inspired by the aforementioned discussion, this paper mainly focuses on designing the prescribed-time platooning controller for a class of CAVs subject to stochastic actuator faults. The primary key findings of the proposed study are listed as follows:

-

1.

This paper explores the problem of prescribed-time stability and adaptive RBFNN state observer-based platooning control design for CAV systems with stochastic actuator faults.

-

2.

Due to limitations of velocity and acceleration sensors, only position is used for feedback, unlike control and estimator designs from existing results12.

-

3.

The proposed adaptive state observer uses an RBFNN-based algorithm instead of a linear state observer to estimate the unknown dynamic effects, which significantly enhances the robustness of the proposed control design.

Finally, the numerical simulations are provided to validate the effectiveness and applicability of the proposed control design policy.

Problem statement and preliminaries

Dynamics of connected autonomous vehicle network

Consider a connected autonomous vehicle network with one leader vehicle (labeled as 0) and N follower vehicles. The dynamics of the leader vehicle is chosen as

where \(p_0(t)\), \(v_0(t)\), and \(a_0(t)\) are the position, velocity, and acceleration of the leader vehicle, respectively; \(u_0(t)\) denotes the exogenous input of the leader vehicle platoon at time t; \(\tau _0\) is the engine time constant. Similarly, the follower vehicle dynamics can be expressed as follows,

where \(p_i(t)\), \(v_i(t)\), and \(a_i(t)\ (i=\{1,2,\ldots ,N\})\) are the position, velocity, and acceleration of the follower vehicles, respectively, with \(f_i(v_i,a_i,t)=-\frac{1}{m_i\tau _i}\Big [c_i(v_i^2+2\tau _iv_ia_i)+\Xi _i\Big ]\). Here, \(c_i\) and \(\Xi _i\) denote the air resistance and road slope of i-th vehicle, respectively. The abstract form of Eqs. (1) and (2) can be expressed as follows,

where \(x_i(t)=\begin{bmatrix} p_i(t)\\ v_i(t)\\ a_i(t) \end{bmatrix}\ (i=0,1,2,\ldots ,N)\), \(A_i=\begin{bmatrix} 0& 1& 0\\ 0& 0& 1\\ 0& 0& -\frac{1}{\tau _i} \end{bmatrix},\ B_i=\begin{bmatrix} 0\\ 0\\ \frac{1}{m_i\tau _i} \end{bmatrix}\) and \(B_f=B_d=\begin{bmatrix} 0\\ 0\\ 1 \end{bmatrix}.\)

Control objectives

The objective of this paper is to design a distributed platooning controller for each following vehicle, addressing input delays, unknown dynamics, and external disturbances, while meeting the following criteria. To enhance road efficiency, ensure string stability, and eliminate nonzero initial spacing errors, the constant time headway (CTH) policy is adopted:

where \(q_{1i}(t)=d_i(t)-h^c_i(t),\) with \(d_i(t) = p_{i-1}(t) - p_i(t) - l_i, \ \ h^c_i(t)=\Delta _{i} +h v_i(t)\), \(\Theta _i(t)= \left( q_{1i}(0) + \dot{q}_{1i}(0) t + \frac{1}{2} \ddot{q}_{1i}(0)\right.\)

\(\left. \times t^2 \right) e^{-{ \varpi }_i t^2}\). Here, \({ \varpi }_i\), \(l_i\), \(\Delta _{i},\) and h, denote a positive constant, the length of vehicle i, the given minimum distance between the vehicle i and \(i-1\), and h denote the time headway, respectively. Note that the auxiliary function \(\Theta _i(t)\) is employed in the CTH policy (4) to ensure the satisfaction of the prescribed performance control precondition of zero initial spacing error26. That is, \(\epsilon _i(0)= 0, \ \ \dot{\epsilon }_i(0) = 0, \ \ \ddot{\epsilon }_i(0) = 0\).

Consequently, the platooning error system can be expressed as follows

where \(A=\begin{bmatrix} 0& 1& 0\\ 0& 0& 1\\ 0& 0& 0 \end{bmatrix},\ B_g=\begin{bmatrix} 0\\ 0\\ 1 \end{bmatrix}\) \(g_i(a_{i-1}(t),a_i(t),v_i(t),t)=a_{i-1}(t)-a_i(t)+h\frac{1}{\tau _i}a_i(t)-h(f_i(v_i,a_i,t)+d_i(t))- \ddot{q}_{1i}(0)e^{-{ \varpi }_i t^2}.\) This study aims to establish a control methodology for the platooning of vehicles based on the following criteria regardless of external disturbances:

-

1.

Individual vehicle stability: Individual vehicle stability in platooning control ensures that each vehicle maintains its own stable behavior and performance in real time, despite disturbances or control variations.

-

2.

String stability The tracking errors do not increase along the platoon, stated mathematically as:

$$\begin{aligned} |E_N(s)| \le |E_{N-1}(s)| \le \cdots \le |E_1(s)| \end{aligned}$$(6)i.e., the error transfer function \(\frac{E_{i+1}(s)}{E_i(s)} \le 1\) for all i, where \(E_i(s)\) denotes the Laplace transform of \(e_i(t)\).

Remark 1

It should be noted that Eq. (6) defines string stability, which ensures that tracking errors do not amplify along the platoon. Several studies have examined string stability under stochastic fault scenarios, focusing on probabilistic approaches to model uncertainties and faults. For instance15,16, investigated fault-tolerant control using stochastic techniques but did not account for unknown dynamics explicitly. Unlike these approaches, the proposed method incorporates neural networks to address unknown dynamics while ensuring fault tolerance and maintaining string stability. This integration provides a more comprehensive solution for handling uncertainties in connected autonomous vehicles.

Prescribed-time control

First, a time-varying scaling function is introduced as follows:

where \(\iota > 2\) is any real number, and T is the settling time. Note that \(\mu ^{-\iota }\) is monotonically decreasing on [0, T), with \(\mu ^{-\iota }(0) = 1\) and \(\lim _{t \rightarrow T} \mu ^{-\iota }(t) = 0\). In addition,

Lemma 1

Consider a system \(\dot{x}(t) = f(t, x(t))\), \(t \in \mathbb {R}^+\), \(x(0) = x_0\). Let \(V(x(t), t) : U \times \mathbb {R}^+ \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) be a continuously differentiable function and \(U \subset \mathbb {R}^m\) be a domain containing the origin. If there exists a real constant \(b > 0\) such that

and

on \([0, \infty )\), where \(\dot{V} = \left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial x}\right) (x) f(t, x)\), then the origin of system \(\dot{x}(t)\) is prescribed-time stable with the prescribed time T given in (7). If \(U = \mathbb {R}^m\), then the system \(\dot{x}(t)\) is globally prescribed-time stable with the prescribed time T. In addition, for \(t \in [0, T)\), it holds that \(V(t) \le \mu ^{-2} e^{-bt} V(0)\), and for \(t \in [T, \infty )\), it holds that \(V(t) \equiv 0\).

To achieve the desired formation of prescribed-time platooning control law can be expressed as follows

where \(K_i^a=[K^a_{i0}\ K_{i1}^a\ K_{i2}^a]\in \mathbb {R}^3,\) \(\xi _1(t)=\sum \nolimits _{j=1}^Nc_{ij}[e_i(t)-e_j(t)]+ e_i(t)\) with \(a=1,2,3\) the platooning control gain matrix to be determined. Furthermore, \(\hat{x}_i(t)\) and \(\hat{\beta }_{g,i}\psi _w(\hat{x}_i(t))\) are the estimates of the state vector \(x_i(t)\) and the effect of the unknown nonlinear function \(g_i(a_{i-1}(t),a_i(t),v_i(t),t)\), respectively, which will be specified later. This study, however, assumes that only position measurements are available as feedback for control design purposes. Therefore, the control law (11) can be expressed in terms of output and its derivatives instead of all states as follows,

where output: \(\xi _2(t)=\sum \nolimits _{j=1}^Na_{ij}(\bar{y}_i^{(l)}(t)-\bar{y}_j^{(l)}(t))+\bar{y}_{i}^{(l)}(t)\). Since calculating the derivatives of sensor measurements is difficult in practice, they are approximated by using finite difference formulas as follows

where h is the small positive constant. From the finite difference relations in (12), the control law can be approximated as follows

where \(\bar{K}_{il}=(-1)^l\sum \nolimits _{j=i}^2\frac{j!}{i!(j-i)!}\frac{1}{h^j}K_{ij},\ \ l=0,1,2\) and \(\xi _3(t)=\sum \nolimits _{j=1}^Na_{ij}(\bar{y}_{i}(t-lh)-\bar{y}_{j}(t-lh))+ \bar{y}_{i}(t-lh)\). On the other hand, it is impossible to store all continuous sensor measurements in practice. Therefore, the above controller is converted into a sampled-data controller by using zero-order hold as follows,

where \(t\in [t_k, t_{k+1})\) with \(t_k=kh\ \ k\in \mathbb {N}\) is the sampling instant and h denotes the sampling period, and we set \(\bar{y}_i(t)=\bar{y}_i(0)\) for all \(t<0\).

For the design of an effective platooning control law (13), determining both the control gains \(\bar{K}_l\) and the maximum sampling period h is essential. To achieve the desired inner-vehicle stability of the connected vehicle network formed by (2) and (18) under control law (13), a systematic stability analysis is necessary. For this, we consider the following lemma.

In addition, by using the fundamental theorem of calculus, the following relations are true

According to Lemma 1 in24 the above equation can be further simplified as

Since the error system dynamics (4) has relative degree three, their output derivatives satisfy

From the Eqs. (17) and (16), with a stochastic actuator fault \(\delta (t)\) with mean \(\bar{\delta }\) and variance \(c^2\) the control law (15) can be expressed as follows:

where \(\alpha _{il}(t)=-K_{il}\int _{t_k}^t\tilde{y}^{\prime }_{il}(s)\textrm{d}s\) and \(\theta _{im}(t)=-K_m\int ^{t}_{t-mh} \psi _m(t - s) \bar{y}_i^{(m+1)}(s)\textrm{d}s.\) Furthermore, based on the definition of system matrices A and C, we have \(\sum \nolimits _{l=0}^2K_{il}CA^{(l)}=K_i\).

RBFNN-based adaptive state observer

In the following, by adopting the reinforcement learning method, we construct a neural network observer for state \(x(t)\) estimation from sampled output data:

where \(\hat{x}(t) \in \mathbb {R}^n\) is the observer state, and the RBFNN term \(\hat{\theta }_{gi}^\top \psi _g(\hat{\epsilon }_i(t))\) is used to approximate \(g_i(a_{i-1}(t),a_i(t),v_i(t),t)\), which will be specified later. In the following, the RBFNN used in the observer design is specified. The RBFNN contains an input layer of \(n\) nodes, a hidden layer of \(l\) nodes, and a linear output layer of 1 node. The time-varying weights and basis function vector are denoted by \(\hat{\theta }_g(t) \in \mathbb {R}^l\) and \(\psi _g : \mathbb {R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb {R}^l\), respectively, where the \(j\)-th component of \(\psi _g\) is defined as:

with \(c_j \in \mathbb {R}\) the center of the receptive field and \(0 < \sigma _j \le 1\) the width of the Gaussian function. It is well known that an RBFNN has the so-called universal approximation property, which allows it to learn any continuous function over \(Z \subset \mathbb {R}^n\) from data and to achieve the approximation of the function as follows:

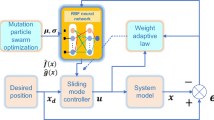

where \(\theta _g^*\) is the optimal weight vector obtained from training data, and \(\vartheta\) is upper bounded by \(\vartheta ^*\). The overall control system block-diagram is shown in Fig. 1.

Main results

In this section, the stochastic prescribed-time stabilization criterion for the platooning error system (5) is developed using linear matrix inequalities. The first theorem derives the stability criterion for the error system (5) assuming the gain matrix \(K=\begin{bmatrix} K_0&K_1&K_2 \end{bmatrix}\) of the continuous output derivative-dependent controller (16) is known. The second theorem provides sufficient stability conditions for determining the controller gain matrices. Based on the separation principle, the observer and controller designs are independent. The proposed RBFNN-based adaptive observer efficiently estimates and compensates for the effect of unknown dynamics \(g_i(a_{i-1}(t), a_i(t), v_i(t), t)\), and the stability condition for controller design is developed, followed by a discussion on the stability of the observer in the next theorem.

Theorem 1

For given sampling period \(h>0\), \(c\in (0,\ 1),\) controller gain matrix \(K_i=\begin{bmatrix} K_{i0}&K_{i1}&K_{i2} \end{bmatrix}\), \(L_i=\begin{bmatrix} l_{i1}&l_{i2}&l_{i3} \end{bmatrix}\) and constants \({ \varpi }>0\), and \(\gamma >0\), the closed-loop error system (5) with controller (17) is mean-square prescribed-time stable,

-

(i)

If there exist suitable dimension block diagonal matrices \(\mathscr {Q}_q>0, \ \ (q=1,2,\ldots ,6)\) such that \(\Gamma :=\begin{bmatrix} { \Omega }& \Theta _1^T& c\Theta _2^T\\ \#& -S& 0\\ \#& \#& -S\end{bmatrix}<0\), where symmetric matrix \({ \Omega }=[{ \omega }_{ij}]_{7\times 7}\) with its nonzero elements are given as \({ \omega }_{1,1}=\mathscr {Q}_1\bar{\mathscr {D}}+\bar{\mathscr {D}_i}^T\mathscr {Q}_1+2{ \varpi }\mathscr {Q}_1+\sum \limits _{m=0}^1h^2e^{2{ \varpi } mh}(I_N\otimes CA_i^{m+1})^T\mathscr {K}_{im}^T\mathscr {Q}_{m+2}\mathscr {K}_m(I_N\otimes CA_i^{m+1})\)\(+\frac{h^2}{4}(I_N\otimes CA_i^2)^T\mathscr {K}_1^T\mathscr {Q}_{5}\mathscr {K}_{1}(I_N\otimes CA_i^2),\) \({ \omega }_{1,2}={ \omega }_{1,3}={ \omega }_{1,4}={ \omega }_{1,5}={ \omega }_{1,6}=\mathscr {Q}_1\mathscr {B}_{H},\ { \omega }_{1,7}=\mathscr {Q}_1(I_N\otimes B),\)\({ \omega }_{2,2}=-\frac{{ \omega }^2}{4}e^{-2{ \varpi } h}\mathscr {Q}_2,\ { \omega }_{3,3}=-\frac{{ \omega }^2}{4}e^{-2{ \varpi } h}\mathscr {Q}_3,\ { \omega }_{4,4}=-\frac{{ \omega }^2}{4}e^{-2{ \varpi } h}\mathscr {Q}_4,\) \({ \omega }_{5,5}=-e^{-2{ \varpi } h}\mathscr {Q}_5,\ { \omega }_{6,6}=-e^{-4{ \varpi } h}\mathscr {Q}_6,\ { \omega }_{7,7}=-\gamma I_N,\) and \(\Theta _1=hS\mathscr {K}_2CA^2\Big [ \bar{\mathscr {D}}\ \ \mathscr {B}_H\ \ \mathscr {B}_H\ \ \mathscr {B}_H\ \ \mathscr {B}_H\ \ \mathscr {B}_H\ \ (I_N\otimes B) \Big ],\) and \(\Theta _2=hS\mathscr {K}_2CA^2\Big [ \mathscr {B}_H\left( I_N\otimes K\right) \ \ \mathscr {B}_H\ \ \mathscr {B}_H\ \mathscr {B}_H\ \ \mathscr {B}_H\ \ \mathscr {B}_H\ \ 0 \Big]\) with \(S=e^{4{ \varpi } h}\mathscr {Q}_4+\mathscr {Q}_6.\)

-

(ii)

For any \({ \varpi }\) belonging to the interval \((0, \bar{{ \varpi }})\), the feasibility of \(\Theta <0\) in (i) is ensured when considering sufficiently small \(h > 0\) and \(\frac{1}{\gamma } > 0\). This implies that if the controller design in (13) is continuous, the error system (5) with \(u_0(t) \equiv 0\) exhibits exponential convergence with a decay rate of \({ \varpi } > 0.\)

Proof

To perform the stability analysis, the following Lyapunov-Krasovskii functional candidate for error system (5) is considered:

where

where \(\phi _m(s)=\int _s^{mh}\psi _m(\mu )\textrm{d}\mu\) and \(\mathscr {Q}_q=(I_N\otimes \bar{Q}_q)>0\ \ (q=1,2,\ldots ,6)\). It should be noted that the positive definiteness of \(V_1(\epsilon (t))\) and \(V_2(\epsilon (t))\) is guaranteed by the exponential Wirtinger inequality. Now, we calculate the stochastic time derivative of \(V_m(\epsilon (t))\) along the trajectories of the closed-loop system (5)

Furthermore, by applying Jensen’s inequality (Lemma 2 in24) with \(\rho (s)=\dot{\psi }_m(t-s)\) for the integral term in the above inequality, we get

By differentiating (25), we get

In addition to this, from the definition of \(\psi _m(t), \ m=1,2\) satisfies

Subsequently from (26) and (27), the Eq. (25) can be written as

From the definition \(\phi _i(t)\), it satisfies \(\phi _m(0)=\int _{0}^{ih}\psi _m(s)\textrm{d}s=\frac{mh}{2},\) \(\phi _m(mh)=0\), and \(\dot{\phi }_m(t)=-\psi _m(t)<0\). It implies that

Again applying Jensen’s inequality (Lemma 2 in24) \(\rho (s)=\psi _m(t-s)\) for the integral term in the above equation is bounded by

Since the platooning error system (5) with position measurement output is a linear time-invariant system with relative degree 3, it implies that \(\bar{y}^{(l)}(t)=(I_N\otimes CA^l)\epsilon (t),\ \ (l=0,1,2)\) and \(\dddot{y}(t)=(I_N\otimes CA^2)\dot{e}(t)\). Using this fact, summing the (22), (23), (27), (30) and taking mathematical expectation, we get

where \(\eta ^T(t)=\Big [e^T(t) \ \alpha _0^T(t) \ \alpha _1^T(t) \ \alpha _2^T(t) \ \theta _1^T(t) \ \theta _2^T(t) \ \hat{u}_0^T(t)\Big ]\) and \({ \Omega }\) is defined in the statement of the theorem. From the dynamics of the error system and using Schur complement, if the inequality \(\Gamma <0\) satisfies

Subsequently, \(V(\epsilon (t)) \le e^{-2{ \varpi }(t-h)} V(e_0) + (1 - e^{-2{ \varpi }(t-h)}) |\hat{u}_0(t)|^2, t \ge 2h.\) In addition, according to the definition of \(V(\epsilon (t))\) in (21), it follows that

for certain constants \({ \varpi }_l > 0\ (l = 0, 1)\). It implies that the error system (5) under the controller satisfies prescribed-time stability.

Now, we prove the second part of Theorem 1. Assuming that platoon formation tracking for system (5) is prescribed-time stability achieved with \(u_0(t)\equiv 0\) a decay rate \(\bar{{ \varpi }} > 0\), for any \({ \varpi } \in (0, \bar{{ \varpi }})\) if there exists a matrix \(\mathscr {Q}_1>0\) such that,

Furthermore, if we choose \(\mathscr {Q}_l= gI_N\ (l = 2,3,\ldots ,6)\) in \(\Theta\) composed from the statement of the theorem. According to Schur complement, \(\Theta <0\) is identical to

where \(\tilde{\Gamma }_{11}= \mathscr {Q}_1\bar{\mathscr {D}} + \bar{\mathscr {D}}^T \mathscr {Q}_1 + 2{ \varpi } \mathscr {Q}_1 + \mathscr {O}(h)+\frac{1}{\gamma }(I_N \otimes B B^T)\) Since \(\mathscr {O}(h) + \frac{1}{\gamma }(I_N \otimes B B^T) \rightarrow 0\) for \(h \rightarrow 0\) and \(\frac{1}{\gamma } \rightarrow 0\), inequality (33) leads to (34) for sufficiently small positive constants \(h\) and \(\frac{1}{\gamma }\). Thus, matrix inequality \(\Theta <0\) can be true for sufficiently small \(h > 0\) and \(\frac{1}{\gamma } > 0\) . Therefore, it completes the proof. \(\square\)

Utilizing the given gain matrix \(\mathscr {K}=\begin{bmatrix} \mathscr {K}_0&\mathscr {K}_1&\mathscr {K}_2 \end{bmatrix}\) and the maximum allowable feasible sampling period h obtained by Theorem 1, the control gains \(\bar{K}_l\) of the sampled-data controller (13) are calculated using the relation \(\bar{K}_l=(-1)^l\sum \nolimits _{j=i}^2\frac{j!}{i!(j-i)!}\frac{1}{h^j}\mathscr {K}_j,\ \ l=0,1,2\). Now, continuous system control gains \(K_i\) are determined using the pole-placement algorithm.

Numerical simulations

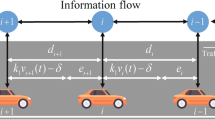

This section presents simulation results demonstrating the effectiveness of reliable platooning control for CAVs and performance recovery against stochastic actuator faults. The scenario includes one leader and five followers in an LF-type platoon, with follower vehicles 2 and 4 affected by stochastic actuator faults. Additionally, followers have uncertain dynamics and leader control input under a leader-bidirectional information flow topology. All constraints are shown in Fig. 2.

Leader-bidirectional information flow topology of Example8.

The dynamical behavior of the i-th vehicle is described by system (2) with \(\tau _i=0.5+0.05i\ s\) \(m=150 kg\); \(c=0.5,\) \(\Xi =236,\) and \(l=2\). In platoon driving, the desired distance between consecutive platoon members is taken as \(d_{safe}=7\ m\) By considering \({ \varpi }=10^{-3},\) \(\gamma =1000\), and the mathematical expectation of the stochastic actuator fault variable is chosen as \(\bar{\delta }=\text{ diag }\{1,\ 0.8,\ 1, \ 0.9,\ 1\}\), solving the stability conditions of Theorem 1 output derivative controller gain is obtained due to the constraints; the gain values are not displayed here. Subsequently, using this gain value and solving the proposed stability conditions in Theorem 1, the maximum allowable sampling period is obtained as \(h=0.0577\), and the control gains of the delay-dependent sampled-data controller can be calculated. Under these control gains, the state response curves position, velocity, and control input of the vehicles are plotted in Figs. 3, 4, 5 and 6, respectively. Specifically, the position and velocity trajectories of the vehicles are depicted in Figs. 3 and Fig. 4, respectively. The corresponding control performance graph is shown in Fig. 5. From these figures, it can be easily seen that vehicle running with the required platooning behavior also all vehicles velocity equally matched with in 10 s by the proposed controller. In addition, the state trajectories of platooning error of all vehicles in the connected network are plotted in Fig. 6. Based on these figures, we can observe that the simulated platoon meets performance requirements for spacing, stability, and resilience during the simulation period of \(T=30\ s\).

The proposed control algorithm determines the tolerable sampling time with various mean values \(\bar{\delta }\), displayed in Table 1. From the table, the value of the maximum allowable sampling period decreases when \(\bar{\delta }\) increases. It is confirmed that the control update must be increased when the actuator fault probability increases. Furthermore, the maximum allowable sampling periods for various decay rates \(\varpi\) are presented in Table 2. When increasing the decay rate \(\varpi\) reduces the feasible maximum allowable sampling period. The control input without actuator fault is displayed in Fig. 6. This case can be deduced from Theorem 1 by setting \(\bar{\delta }=1\). The simulation results confirm that the proposed adaptive RBFNN observer-based control algorithm ensures effective platooning performance, even with time-varying leader input, stochastic actuator faults, and uncertain dynamics.

Conclusions

In this brief, robust RBFNN adaptive state observer-based platooning control problem for connected autonomous vehicles in the presence of uncertain dynamics parameters and actuator faults. Specifically, the actuator fault is expressed in terms of a Bernoulli-distributed stochastic variable. The technique is combined with traditional state observer techniques to compensate for uncertain dynamics. Lyapunov stability theory is used to verify string stability and individual vehicle stability. Using a leader vehicle and five followers, the developed controller design is verified numerically with no loss of generality. Despite uncertain dynamics and faults, the proposed controller ensures platooning regardless of leader vehicle input based on simulation results.

Data availibility

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Nguyen, T. L., Mai, X. S. & Dao, P. N. A robust distributed model predictive control strategy for leader-follower formation control of multiple perturbed wheeled mobile robotics. Eur. J. Control. 81, 101160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcon.2024.101160 (2025).

Rao, P. & Li, X. Cooperative formation of self-propelled vehicles with directed communications. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs. 67, 315–319. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSII.2019.2904640 (2020).

Muzahid, A. J. M. et al. Multiple vehicle cooperation and collision avoidance in automated vehicles: Survey and an AI-enabled conceptual framework. Sci Rep. 13, 603. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-27026-9 (2023).

Ge, X. et al. Resilient and safe platooning control of connected automated vehicles against intermittent Denial-of-Service Attacks. IEEE-CAA J. Autom. 10, 1234–1251. https://doi.org/10.1109/JAS.2022.105845 (2023).

Aruna, T. M. et al. Geospatial data for peer-to-peer communication among autonomous vehicles using optimized machine learning algorithm. Sci. Rep. 14, 20245. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71197-6 (2024).

Ma, Y.-S. et al. Data-driven distributed vehicle platoon control for heterogeneous nonlinear vehicle systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 25, 2373–2381. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2023.3321750 (2024).

Bigman, Y. E. & Gray, K. Life and death decisions of autonomous vehicles. Nature 579, E1–E2. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-1987-4 (2020).

Selvaraj, P. et al. Event-triggered position scheduling-based platooning control design for automated vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intelli. Veh. 1, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2023.3321750 (2024).

Li, Z. et al. String stability analysis for vehicle platooning under unreliable communication links with event-triggered strategy. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 68, 2152–2164. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2019.2891681 (2019).

Sun, Z. et al. Finite-time control of vehicular platoons with global prescribed performance and actuator nonlinearities. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 9, 1768–1779. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIV.2023.3292393 (2024).

Polyakov, A. Nonlinear feedback design for fixed-time stabilization of linear control systems. IEEE Trans. Automat. Control. 57, 2106–2110. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAC.2011.2179869 (2012).

Gao, Z., Zhang, Y. & Guo, G. Prescribed-time control of vehicular platoons based on a disturbance observer. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs. 69, 3789–3793. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSII.2022.3175368 (2022).

Song, Y., Ye, H. & Lewis, F. L. Prescribed-time control and its latest developments. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 53, 4102–4116. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSMC.2023.3240751 (2023).

Lu, K., Dai, S.-L. & Jin, X. Fixed-time rigidity-based formation maneuvering for nonholonomic multirobot systems With prescribed performance. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 54, 2129–2141. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCYB.2022.3226297 (2024).

Rahimi, F. An online fault-tolerant control approach based on policy iteration algorithm for nonlinear time-delay systems. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 1, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207721.2024.2440785 (2024).

Rahimi, F. Adaptive dynamic programming-based fault tolerant control for nonlinear time-delay systems. Chaos Solition Fract. 188, 115544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2024.115544 (2024).

Han, J. et al. Distributed finite-time safety consensus control of vehicle platoon with sensor and actuator failures. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 72, 162–175. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2022.3203056 (2023).

Wang, Z., Lei, J. & Zheng, G. “Neural network adaptive admittance control for improving position/force tracking accuracy of fracture reduction robot,’’ Trans. Inst. Meas. Control.[SPACE]https://doi.org/10.1177/01423312241286322 (2025).

Nguyen, K. et al. Formation control scheme with reinforcement learning strategy for a group of multiple surface vehicles. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 34, 2252–2279. https://doi.org/10.1002/rnc.7083 (2023).

Vincent, T. L., Galarza, C. & Khargonekar, P. P. Adaptive estimation using multiple models and neural networks. IFAC Proc. 31, 149–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-6670(17)38937-1 (1998).

Yanqi, Z. et al. Neural networks-based adaptive dynamic surface control for vehicle active suspension systems with time-varying displacement constraints. Neurocomputing. 408, 176–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2019.08.102 (2020).

Wei, J. et al. Adaptive neural control of connected vehicular platoons with actuator faults and constraints. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 8, 3647–3656. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIV.2023.3263843 (2023).

Zhou, H. et al. A unified longitudinal trajectory dataset for automated vehicles. Sci Data. 11, 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03795-y (2024).

Selivanov, A. & Fridman, E. An improved time-delay implementation of derivative-dependent feedback. Automatica 98, 269–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.automatica.2018.09.035 (2018).

Sangapu, S. C. et al. Impact of class imbalance in VeReMi dataset for misbehavior detection in autonomous vehicles. Soft Comput. 1, 1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-023-08003-4 (2023).

Zhang, C. L. & Guo, G. Prescribed performance sliding mode control of vehicular platoons with input delays. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 25, 11068–11076. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2024.3368520 (2024).

Sakthivel, R. et al. State estimation and dissipative-based control design for vehicle lateral dynamics with probabilistic faults. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 65, 7193–7201. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2018.2793253 (2018).

Zhang, J., Peng, C. & Xie, X. Platooning control of vehicular systems by using sampled positions. IEEE Trans. Circ. Syst. II Express Briefs 70, 2435–2439. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSII.2023.3242298 (2023).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Devanathan, B., Selvaraj, P., Suyampulingam, A. et al. Prescribed time reliable platooning control for connected autonomous vehicles using neural network adaptive estimator approach. Sci Rep 15, 6840 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89887-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89887-0