Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) ranks among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. The objective was to evaluate the burden of AD and other dementias among the countries of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region by age and sex from 1990 to 2021. The data were sourced from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study 2021. The estimates are presented as counts and age-standardised rates per 100,000 accompanied by 95% uncertainty intervals (UIs). In 2021, AD and other dementias recorded an age-standardised prevalence of 772.7 per 100,000 in the MENA region (95% UI 671.2–877.6 per 100,000). This rate decreased by 4.9% in comparison to 1990, marking a statistically significant change. AD and other dementias also accounted for approximately 73.79 thousand deaths in the region in 2021, with the age-standardised rate decreasing by 8.6% compared to 1990. Moreover, the disability-adjusted life years (DALY) rate was 476.3 per 100,000 population (95% UI 225.6–1004.2), representing a 7.7% decrease from 1990 to 2021. Lebanon registered the highest point prevalence per 100,000 at 828.25, while the United Arab Emirates recorded the lowest at 652.43. The age-standardised point prevalence decreased from 1990 to 2021 in 13 of the MENA countries, while no significant changes were observed in eight of countries. Additionally, in 2021, women experienced higher prevalence rates, DALYs, compared to men. In the MENA region, age-standardised dementia prevalence rose with age in both sexes. The burden of dementia in MENA has decreased from 1990 to 2021, but it remains higher than global estimates. Furthermore, the findings indicate that dementia imposes a greater burden on the female population compared to males. To achieve a more accurate estimation of the burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, more systematic studies in low- to middle-income countries within the MENA region are required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) ranks among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide, characterised by progressive cognitive decline, behavioral changes, and eventual loss of independent function. In AD, the brain pathologically accumulates amyloid-beta plaques and tau protein neurofibrillary tangles, resulting in synaptic dysfunction and neuronal death. Neuroinflammation and oxidative stress also play crucial roles in the disease’s progression1,2. In addition to aging, which is the principal risk factor, other significant risk factors include genetic predisposition (such as the presence of the APOE ε4 allele), cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and lifestyle factors like physical inactivity and poor diet1,3.

In 2019, dementia was responsible for 44 million DALYs globally, ranking as the 7th leading cause of death and disability combined, and the 3rd leading cause among individuals aged 70 and older4. The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study 2019 found that dementia accounted for about 2.5% of total global DALYs5. Previous research on dementia’s impact found that, in 2019, the MENA region experienced 2.5 million cases and 70.5 thousand deaths attributable to the condition6. AD accounts for 60–80% of all dementia cases worldwide, making it the most common form of this condition1,7. The global burden of AD is rising, primarily driven by aging populations and increased life expectancies. This trend is especially evident in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, where rapid demographic and epidemiological transitions present unique challenges for public health systems8. As the MENA region experiences a significant rise in several risk factors associated with AD, a rapid increase in the disease’s prevalence is anticipated in the coming decades. The population in the MENA region is aging rapidly, with the proportion of individuals older than 60 expected to increase substantially by 20509. Furthermore, there is a marked increase in the prevalence of cardiovascular diseases and diabetes, both of which are significant risk factors for AD10.

Over the past few decades, the MENA region has experienced substantial socioeconomic transformations, including improvements in healthcare infrastructure, greater access to education, and alterations in lifestyle factors like diet and physical activity11. These transformations have important implications for the epidemiology of AD. Improved healthcare and increased longevity can lead to higher prevalence rates of AD, while changes in lifestyle and diet can influence the risk factors associated with the disease3. For example, sedentary lifestyles and poor dietary habits are becoming more common, contributing to obesity and metabolic syndromes, which are risk factors for AD12. Furthermore, the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic has severely affected healthcare systems worldwide, disrupting the diagnosis, treatment, and management of chronic diseases, including AD, and the MENA region is no exception13. The pandemic has led to delays in diagnosis and treatment, the suspension of routine healthcare services, and changes in health-seeking behaviors, which may have affected AD’s incidence and outcomes14. Understanding these impacts is crucial for crafting adaptive public health strategies in the post-pandemic era15.

The burden of AD is multifaceted and extends beyond the individuals directly affected by the disease. It encompasses not only the direct impact on patients’ quality of life but also imposes indirect strains on caregivers, families, and healthcare systems16,17. AD places a substantial economic burden on societies, including increased healthcare costs, long-term care expenses, and reduced productivity18,19. A 2019 study estimated that dementia care in the MENA region incurred costs of approximately $2.1 billion. This expenditure has been increasing at an annual rate of 8.2% since 2000 and is forecast to reach $57.9 billion by 2050. In comparison, the global annual growth rate in dementia-related spending from 2000 to 2019 was lower, at 4.5%20. Therefore, it is crucial to comprehensively evaluate the burden of AD, taking into account its multiple dimensions and their interplay within the MENA region.

Understanding the burden of AD is essential for informing policymakers and practitioners. Accurate and up-to-date epidemiological data can aid in developing region-specific strategies to address the growing burden of AD21. These strategies may include public health campaigns to increase awareness, early detection programs, and the development of support systems for patients and caregivers6. Additionally, understanding the burden of AD can help advocate for increased funding and resources for Alzheimer’s research and care on both regional and national levels22.

Given the urgent need for current literature on the burden of AD in the MENA region, our research aimed to provide a comprehensive analysis of trends in incidence, prevalence, mortality, and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) associated with AD from 1990 to 202118,23. By examining these trends, we sought to gain insights into the distribution and determinants of AD in this region, thereby identifying areas that require targeted interventions24. Understanding both the current and projected burden of AD is essential for developing of effective interventions, early detection strategies, and management plans. Additionally, this knowledge is vital for informing resource allocation, enhancing healthcare infrastructure, and training healthcare professionals to meet the growing demand for dementia care25. Therefore, our study focused on detailing the DALYs, prevalence, and mortality rates of dementia in the MENA region from 1990 to 2021, with stratification by age, sex, and Socio-demographic Index (SDI).

Methods

Overview

GBD 2021 undertook a thorough investigation of 371 diseases and injuries across a global framework of 204 territories and countries, divided into 21 regions, spanning from 1990 to 202126. This study focuses on AD within the MENA region, providing detailed information on the mortality, prevalence, and DALYs across its 21 countries over this same time period. For a comprehensive understanding of GBD 2021 methodology and its developments since GBD 2019, consult the associated publication26. The estimates for fatal and non-fatal outcomes, along with their supplementary methodological details, can be found at https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/ and http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool.

Case definition and data sources

Dementia is a severe, progressive, and chronic neurological disorder, marked by significant memory impairment and various neurological dysfunctions. In GBD 2021, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) utilised the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) editions III, IV, or V, or the ICD case definitions as our reference points. A broad spectrum of diagnostic and screening tools are available, including the Clinical Dementia Rating scale (CDR), Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), and Geriatric Mental State (GMS). The CDR serves as our primary reference for evaluating severity. The pertinent ICD-10 codes for dementia are F00, F01, F02, F03, G30, and G31, while the ICD-9 codes include 290, 291.2, 291.8, 294, and 331.

Accepted alternative case definitions for inclusion were diverse and robust, encompassing diagnoses determined by algorithmic modeling, general practitioner data, and clinical records. Additionally, diagnoses utilising the 10/66 algorithm and those applying the NIA-AA (National Institute of Ageing—Alzheimer’s Association) criteria were included, providing a comprehensive approach beyond the traditional ICD or DSM standards.

To refine the estimates of dementia’s burden, IHME integrated a range of data sources. Mortality data were drawn from relative risk studies and linked hospital records to mortality statistics. The GBD also utilised prevalence and incidence data from surveys and administrative sources, such as claims data. Notably, GBD 2021 introduced the use of incidence data in dementia modelling for the first time, offering a more detailed and robust analysis of the condition’s impact.

Beginning with GBD 2019, the methodology for fatal modelling underwent a significant redesign to remove reliance on vital registration data. Instead, IHME focused on extracting data from literature that assessed the relative risk of all-cause mortality linked to dementia exposure. This information was meticulously gathered during a systematic review in PubMed using carefully defined search terms. The resulting dataset was notably heterogeneous, capturing a range of exposure categories, including all dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and cognitive impairment, as well as various factors controlled for in the analyses.

Severity splits

Starting with GBD 2019, the approach to determining severity splits for dementia was comprehensively restructured. A new systematic review was conducted to accurately capture the distribution of individuals across various dementia severity classes within the dementia population. Although several methods are commonly used for assessing severity, GBD used the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale as our reference definition. Furthermore, it was relied on doctor-given diagnoses based upon DSM III, IV, V or ICD case definitions as reference definitions for dementia.

As a neurodegenerative disorder with a broad spectrum of symptom manifestations, dementia requires a variety of classification tools to accurately assess severity levels based on different criteria. Several tools were recognised for classifying severity, including the Clinical Dementia Rating Sum-of-Boxes (CSR-SB), the Blessed Test of Information, Memory, and Concentration (BIMC), and the Global Deterioration Scale (GDS). Additionally, classifications from the Geriatric Mental State Examination (GMS), CAMDEX, DSM-III-R, and Karasawa’s scale were accepted. These tools collectively provide a comprehensive framework for discerning the nuanced severity levels of dementia.

Studies that assessed dementia severity using scales focused solely on cognitive function and memory were excluded, as they did not evaluate the activities of daily living (ADLs). The Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) is a prime example of such scales, and consequently, studies utilising it were omitted from the analysis.

Data processing and disease models

Non-fatal modelling strategy

Initially, prevalence data underwent a process of sex splitting, crosswalking, and age splitting. Studies that provided separate data for age and sex were divided into age- and sex-specific data points. For data labelled as “both” sexes, IHME used MR-BRT to derive a model ratio of female-to-male prevalence, allowing GBD to split these into male- and female-specific data points. Additionally, data points were divided with age ranges exceeding 25 years by applying the global age pattern.

In the initial DisMod-MR 2.1 model 1, which employs Bayesian meta-regression for disease modeling, two country-level covariates were incorporated. Age-standardised education served as an indicator of general brain health and activity, potentially offering protection against dementia, particularly Alzheimer’s disease. Additionally, age-standardised smoking prevalence for both sexes was included as a covariate. This decision was informed by literature indicating a positive correlation between smoking and the risk of developing dementia.

The cause-specific mortality results from the final fatal estimates were integrated into a comprehensive DisMod-MR model (Model 2). To avoid double counting prevalent dementia cases, both under dementia and other causes that can lead to dementia, we adjusted our dementia prevalence figures. This adjustment excluded cases attributable to other conditions such as stroke, Parkinson’s disease, traumatic brain injury, and Down’s syndrome. To achieve this, data from the Aging, Demographics, and Memory study (ADAMS) were utilised alongside new systematic reviews to estimate the relative risk of developing dementia for each condition included in the ADAMS dataset, specifically stroke, Parkinson’s disease, and TBI. Initially, logistic regression models were employed to predict the likelihood of dementia given each exposure, incorporating age as an additional covariate.

Then these models were applied to forecast the likelihood of developing dementia for each exposure across various ages. By calculating the ratio of the probability of having dementia to the probability of not having dementia at each age, the relative risks were derived. These age-specific relative risks were then integrated into the dementia prevalence estimates produced by the DisMod-MR 2.1 model to compute the population attributable fractions (PAFs) for each cause and age category.

In the final step, the dementia prevalence attributable to each specific cause was estimated by multiplying the PAF by the total prevalence. Then these attributable values from the overall prevalence were subtracted, thereby isolating the prevalence of dementia that is not a result of other GBD causes.

Fatal modelling strategy

Dementia stands out in the GBD project as its mortality and morbidity estimates are modelled together, a necessity due to stark differences between prevalence data and cause of death records. While prevalence data show minimal changes over time, such as from 1990 to 2020, age-standardised mortality rates in high-income countries have risen substantially during the same timeframe. Moreover, the disparity in prevalence between countries is far less pronounced than the variation in death rates assigned to dementia in vital registration data. These pronounced discrepancies were attributed to shifts in coding practices rather than genuine epidemiological changes.

IHME began by leveraging relative risk data from systematic reviews to calculate attributable risk and the GBD estimate of all-cause mortality rates for each time and location. Following this, a comprehensive meta-analysis of the attributable risk data was conducted, incorporating covariates such as age, sex, exposure category (encompassing all dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, cognitive impairment), and whether the research was based on a clinical sample. Various controlled variables were also considered, including educational attainment, cardiovascular disease comorbidities, smoking and alcohol consumption, as well as daily activities or residence in a nursing home. To estimate relative risks, a second Bayesian bias-reduction meta-regression model was employed, using the same systematically reviewed studies. The meta-regression results were utilised to model the number of excess deaths attributable to dementia. This calculation was achieved by multiplying our adjusted estimates (accounting for dementia caused by other GBD diseases) with our estimates of attributable risk.

Compilation of results

For each prevalence, death, or DALY estimate, we also meticulously generated 1000 draws, summing these across age, cause, and location26. This rigorous approach ensured that uncertainty throughout the entire computational process were captured and conveyed. Ninety-five percent uncertainty intervals (UIs) were calculated by selecting the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles from the sorted draws. Age was systematically separated into five-year intervals. Utilising R (version 3.5.2) we produced detailed plots of age-standardised point prevalence, deaths, and DALY rates. To thoroughly investigate the impact of the Socio-demographic Index (SDI) on the burden of AD and other dementias across MENA countries, we applied smoothing splines models, providing a nuanced analysis of these relationships.

Results

The MENA region

In 2021, in the MENA region, the prevalence of AD was 2.68 million cases (95% UI 2.32–3.04 million). In terms of age-standardised rate (ASR) of prevalence, 772.7 patients per 100,000 (95% UI 671.2–877.6) were observed in 2021, which was 4.9% (95% UI 3.7–6.3) lower compared to 1990 (Tables 1 and S1). There were 73.79 thousand (95% UI 18.12–190.47) deaths in 2021, with an ASR of 25.6 (95% UI 6.3–66.8) per 100,000, which was 8.6% (95% UI 2.4–14.1) lower than in 1990 (Tables 1 and S2). Additionally, the number of DALYs attributable to these diseases was 1.56 million (95% UI 0.75–33.14), with an ASR of 476.3 (95% UI 225.6–1004.2) per 100,000, which was also lower in comparison to 1990 (− 7.7% with a 95% UI of − 3.4 to − 11.7) (Tables 1 and S3).

Country level

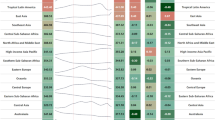

In 2021, the national age-standardised point prevalence of AD ranged from 652.43 to 828.25 cases per 100,000. The highest ASRs were reported in Lebanon [828.25 (95% UI 710.40–948.14)], Turkey [819.36 (95% UI 706.20–936.59)] and Tunisia [791.09 (685.56–901.07)]. In contrast, the United Arab Emirates [652.43 (95% UI 552.16–753.80)], Saudi Arabia [701.74 (95% UI 600.97–807.91)] and Egypt [726.90 (95% UI 630.54–823.49)] had the lowest ASRs (Fig. 1A and Table S1).

Age-standardised point prevalence (a), deaths (b), and DALYs (c) for AD and other types of dementia (per 100,000 population) in the MENA region in 2021, by sex and country (generated from data available from http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool).

In 2021, the age-standardised death rates of AD ranged from 23.36 to 33.27 cases per 100,000 among the MENA nations. Afghanistan [33.27 (95% UI 8.44–89.55)], Libya [28.04 (95% UI 6.73–75.56)], and Qatar [26.54 (95% UI 6.57–73.95)] had the lowest ASRs. Conversely, Sudan [23.36 (95% UI 5.68–62.70)], Jordan [23.37 (95% UI 5.78–64.07)], and the Syrian Arab Republic [23.83 (95% UI 6.08–62.44)] had the lowest (Fig. 1B and Table S2).

In 2021, the national age-standardised DALY rates of dementia ranged from 427.48 to 577.72 cases per 100,000. Afghanistan [577.72 (95% UI 251.23–1271.17)], Libya [502.17 (95% UI 241.77–1123.68)], and Turkey [491.99 (95% UI 236.53–1031.11)] had the highest ASRs. In contrast, the United Arab Emirates [427.48 (95% UI 198.64–928.24)], Sudan [442.22 (95% UI 209.16–934.95)], and Jordan [450.02 (95% UI 219.99–960.28)] had the lowest rates (Fig. 1C and Table S3).

The age-standardised point prevalence decreased from 1990 to 2021 in 13 of the 21 MENA countries, with no significant changes in the rest of the countries. The United Arab Emirates [-9.9 (95% UI − 6.2 to − 13.3)], Yemen [− 9.2 (95% UI − 5.9 to − 12.8)], and the Syrian Arab Republic [− 8.1 (95% UI − 4.6 to − 11.2)] had the largest decrease in the age standardised point prevalence from 1990 to 2021 (Table S1 and Figure S1).

The age-standardised death rates decreased from 1990 to 2021 in the United Arab Emirates [− 16.2 (95% UI − 5.2 to − 26)], Bahrain [− 12.5 (95% UI − 1.3 to − 22.7)], and Iran [− 7.8 (95% UI − 1.8 to −12)]. No significant changes were observed in the remaining countries (Table S2 and Figure S2).

The age-standardised DALY rates of five countries in the MENA region decreased from 1990 to 2021, while there were no significant changes in the remaining countries. The United Arab Emirates [− 15.7 (95% UI − 8.6 to − 22.1)], Turkey [− 10.8 (95% UI − 0.8 to − 20.5)], and Bahrain [− 10.6 (95% UI − 2.6 to − 18.4)] experienced the largest reductions (Table S3 and Figure S3).

Age and sex patterns

In 2021, the prevalence of AD and other dementias increased up to the 80–84 age bracket for both sexes, before declining to the 95+ age category. The age-standardised prevalence of dementia rose with age for both sexes in the MENA region (Fig. 2A).

Number of prevalent cases and prevalence (a), number of death cases and death rate (b), and number of DALYs and DALY rate (c) for AD and other types of dementia (per 100,000 population) in the MENA region, by age and sex in 2021; dotted and dashed lines indicate 95% upper and lower uncertainty intervals, respectively (generated from data available from http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool).

In 2021, the number of deaths for both sexes rose with age to the 85–89 age bracket, then decreased. The age-standardised death rate also rose with age in both sexes (Fig. 2B).

The number of DALYs also increased with age in both sexes to the 80–84 age category, after which it declined. The age-standardised DALY rates increased with increasing age in both sexes (Fig. 2C). Additionally, in all three measures—both in terms of numbers and ASRs—females were the dominant cases in all age groups, although this difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 2A–C).

In 2021, the ratio of MENA/Global DALY rates were generally higher for males across all age ranges, except for the 40–59 age bracket, where the rates were comparable to global figures. For females, the ratio was higher in the 40–44 and 65–84 age groups. The highest MENA/Global DALYs ratio in 2021 was 1.2, observed in males aged 70–79. When compared to 1990 data, it is evident that the MENA/Global DALYs ratio in 2021 was lower or equal across all age groups and both sexes, indicating a decreasing trend over the measurement period (Fig. 3).

The ratio of the MENA region to global AD and other types of dementia DALY rates by age group and sex, 1990–2021 (generated from data available from http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool).

Relationship with the SDI

In 2021, the age standardised DALY rate of dementia decreased as the SDI increased up to 0.4, followed by a slight rise up to an SDI of approximately 0.47. Beyond this point, the rate generally decreased for higher SDIs, with a minor increase observed in the 0.6–0.65 range. The burden of dementia was higher than expected in Afghanistan, Libya, Turkey, Tunisia, Algeria, and Bahrain, while it was lower in Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic, Jordan, and Egypt (Fig. 4).

Age-standardised DALY rates of AD and other types of dementia for 21 countries and territories in 2021, by SDI; expected values based on the SDI and disease rates in all locations are shown as the black line. Each point shows the observed age-standardised DALY rate for each country in 2021 (generated from data available from http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool).

Discussion

In this study, we report the burden of AD in the MENA region using GBD 2021 data and to examine trends from 1990 to 2021. In 2021, the age-standardised prevalence rate (772.7 per 100,000) was 4.9% lower than in 1990. Similarly, the age-standardised death and DALY rates were 8.6% and 7.7% lower than in 1990, respectively. We analysed all 21 MENA countries to compare the burden of dementia among them. The wide variation in prevalence, death, and DALYs across these countries may be attributed to differences in environmental factors, risk factor exposure, genetics, age demographics, healthcare systems, and disparities in access to healthcare. Regarding the age and sex-related burden, females generally exhibited higher rates compared to males, and the burden increased with age; older age groups had higher DALY and death rates. Compared to global data, the burden of dementia in the MENA region was consistently higher or equal to global rates across all ages and both sexes. Considering the SDI of the countries, the burden generally decreased with increasing SDI. However, some countries exhibited higher or lower than expected DALY rates.

In 2021, neurological diseases accounted for 11.1 million deaths globally and were the leading cause of DALYs and YLLs. Alzheimer’s disease ranked second in terms of DALYs for individuals aged 60 and over, following stroke27. In 2019, dementia was one of the leading causes of disability and was the seventh leading cause of death worldwide. Alzheimer’s disease, the predominant form of dementia, was responsible for more than half of all dementia cases28. In the MENA region, the age-standardised point prevalence of dementia increased by 3.0% between 1990 and 2019, while DALY and death rates showed no significant changes6. Notably, the GBD 2016 study indicated that the global age-standardised point prevalence of dementia rose by 1.7% since 19904. Previous research has shown that from 1990 to 2019, the burden of dementia in the MENA region was consistently higher or equal to the global rate4,29, aligning with our findings. In 2019, the global number of Alzheimer’s disease cases had increased by 161% compared to 199030, and projections indicate further increases by 205031. The trends observed in the MENA region aligned with these global patterns6.

The economic burden of dementia in the MENA region has steadily increased between 1990 and 2019, reaching $2.1 billion, with projections estimating it will rise to $57.9 billion by 205032. This increase is attributed to an aging population and improvements in healthcare, which have extended patients’ lifespans. Additionally, it is predicted that the MENA region will experience the greatest increase in the burden of dementia by 205033. However, in 2021, the age-standardised DALY, death, and prevalence rates in the MENA region showed no significant changes compared to 1990.

Using GBD 2021 data, several risk factors were identified as having significant effects on the mortality rate of Alzheimer’s disease, notably tobacco consumption and cardiovascular disease. Tobacco smoking emerged as the most critical risk factor for dementia34. From 1990 to 2019, the prevalence of smoking decreased in nearly all MENA countries. However, despite smoking being the primary risk factor, the burden of dementia continued to rise until 201935. Due to the global focus on tobacco control, the burden attributable to tobacco consumption decreased by 35% worldwide from 1990 to 202136. Consistent with global findings, this study reported a slight decrease in the burden of dementia in the MENA region.

The GBD estimates have limitations, as detailed in the “strengths and limitations” section. Given the importance of evidence-based health policies, a core concept of the GBD Study is that "some data is better than no data". The quality and accuracy of data collection depend on the disease type and local data collection policies, both of which might affect the analysis.

Although alcohol consumption has long been recognised as a risk factor for brain damage and dementia development37, a recent study found that low levels of alcohol consumption may have a protective effect against AD, particularly in women. However, consistent with previous findings, higher levels of alcohol consumption remain a risk factor34. The prevalence of high alcohol consumption decreased in 2021, compared to both 1990 and 2020, which may have contributed to the reduced burden of AD and other dementias36.

Moreover, vascular dementia ranks as the second most prevalent cause of dementia, surpassed only by Alzheimer’s disease. Both symptomatic and asymptomatic vascular lesions significantly contribute to cognitive impairment and might result in vascular dementia38. The declining burden of cerebrovascular accidents, including ischaemic stroke, in the MENA region might be another reason for the observed decrease in AD burden39.

Other risk factors influencing the burden of AD include low education, high fasting blood glucose, high BMI, and high systolic blood pressure40. While the prevalence of smoking and cardiovascular disease has declined, the burden attributable to hypertension, high BMI, and high fasting blood glucose continues to pose a global challenge, with increasing DALYs worldwide36.

The overall demographic changes in the MENA region, including a rise in the working-age population and a reduction in the percentage of the elderly population, might also contribute to the reported slight decrease in the dementia burden observed in our study41,42.

Globally, the burden of dementia has been reported to be higher in females than in males6,43. In our research, we also found that in 2021, the number of prevalent cases, deaths, and DALYs, as well as age-standardised measures, were higher in females than males, a trend expected to continue up to 205033. Several factors may explain these findings. Firstly, there has been an overall increase in life expectancy globally, with women generally living longer than men, as observed over past decades44,45. Since older age is a primary risk factor for developing dementia, the fact that women tend to live longer may result in a higher number of dementia cases among them46. Additionally, age-standardised point prevalence, DALYs, and deaths were also reported to be higher in females. Traditional gender roles, along with differences in education, work, and lifestyle, may impact dementia risk, contributing to what is known as “cognitive reserve”47,48. Historically, men have had more opportunities for higher education and high-skilled occupations than women49,50. Consequently, women may have less cognitive reserve, making them more susceptible to dementia than men51,52. Biological factors and genetics are also significant risk factors for AD53,54,55. For instance, the ApoE4 gene has been linked to the pathogenesis of AD, the most common type of dementia. However, the risk of developing dementia is higher in women with a copy of this gene than in men with this gene, suggesting that AD risk factors may be associated with greater brain ageing in women. The understanding of this phenomenon remains incomplete56,57,58. This difference might also lead to varying responses to AD medications between male and female patients, necessitating individualised treatment approaches.

Consistent with previous findings4,31,33, we observed no clear trends in changes in dementia burden relative to SDI in MENA countries. This could be attributed to improvements in healthcare systems in these countries or a lack of focus on elderly healthcare, which may result in suboptimal care for elderly patients despite residing in higher SDI areas. Additionally, genetic and biological factors, which extend beyond environmental and epigenetic influences, might also play a significant role.

Despite a slight decrease since 1990, the burden of dementia in the MENA region remains higher than the global burden across nearly all ages and both sexes. These results highlight the critical need to address key modifiable risk factors within this region. Factors such as high BMI, high fasting blood glucose, smoking, and low education levels significantly impact the burden of dementia. Altering current trends in exposure to these factors could help reduce this burden in the future59,60. A recent study has shown that many dementia risk factors are highly modifiable, and despite existing barriers and challenges, focusing on these risk factors could help decrease the burden61. As previously mentioned, the burden of dementia is consistently higher in females than in males worldwide, and the MENA region is not an exception. While some factors are biological, many modifiable risk factors disproportionately affect females, and targeting these could help alleviate the burden in this demographic62,63.

Our results highlighted the trends in the burden of dementia from 1990 to 2021 across MENA countries, examining risk factors and variations by age, sex, and SDI. These findings could inform policymaking and planning for effective strategies to address the anticipated increase in dementia burden in the MENA region. Interventions aimed at enhancing prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation could significantly impact patients, their families, caregivers, and society. Such interventions might focus on improving infrastructure, insurance coverage, public awareness, education, risk factors, and addressing resource inequities. As dementia predominantly affects the elderly, who often have other health issues, managing polypharmacy is also crucial. Increased awareness could help in more effectively addressing the needs of the elderly and, if necessary, offering suitable palliative and end-of-life care. Multi-component interventions have been reported as the most effective approach in controlling dementia64,65.

Strengths and limitations

This study provides an updated perspective on the burden of dementia in this region using the most recent data available. The findings are informative and could assist policymakers and stakeholders in addressing the dementia burden in the region by understanding the latest trends. However, like most studies, ours has some limitations. First, the GBD 2021 data collection resulted in wide uncertainty intervals, particularly in data from low and middle-income countries. While the data remain important and useful, the wide uncertainty intervals mean they are less precise. Second, there is a paucity of data and a failure to consistently use standardised case definitions among the included studies, especially among low- and middle-income countries. Additionally, regional factors such as local conflicts and poor health data systems exacerbate these challenges. In the absence of data, precise modeling techniques were employed, but the lack of high-quality data remains a limitation. Third, the definition of AD based on DSM or ICD criteria might lead to misclassifications and discrepancies in reported data. Moreover, another shortcoming of the GBD data was that we were not able to separate the burden of dementia into its different subtypes. Although AD cases are the most prevalent and contribute significantly to the burden, other subtypes could influence our data interpretation. Therefore, it is recommended that dementia be separated into its different subtypes in future cycles of the GBD study. Fourth, the COVID-19 pandemic, occurring during data collection, caused delays and disruptionsin global and national interactions, potentially affecting the data gathering, reporting, or submitting process. As reported in previous studies, the pandemic decreased life expectancy in every GBD super-region from 2019 to 2021. The effect was mostly observed in individuals aged 25 years and older, which includes most AD patients, and was more severe in sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, south Asia, and Latin America regions. Given that this study was conducted on data from the MENA region, the pandemic’s effect should be considered when comparing the results66.

Conclusions

Despite previously reported increases in point prevalence, age-standardised DALYs and deaths due to dementia in the MENA region, as well as projections indicating a rise in the burden of AD up to 2050, our study found that the burden in 2021 was quite similar to that in 1990, with a slight decrease. However, the measures in the MENA region were higher compared to global results and remained higher in females than in males. This underscores the need to target major modifiable risk factors and to establish preventive measures, screening tools, treatment resources, and palliative care centers. Future reports should focus on improving data quality in low- and middle-income countries and include dementia subtypes when reporting the disease burden for a more accurate understanding of AD in the MENA region.

References

2020 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer Dement., 16(3), 391–460 (2020).

Querfurth, H. W. & LaFerla, F. M. Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 362(4), 329–344 (2010).

Livingston, G. et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 396(10248), 413–446 (2020).

Nichols, E. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 18(1), 88–106 (2019).

Vos, T. et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396(10258), 1204–1222 (2020).

Safiri, S. et al. The burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia in the Middle East and North Africa region, 1990–2019. Age Ageing 52(3), 042 (2023).

Prince, M. et al. World Alzheimer report 2015.The global impact of dementia: An analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. In Alzheimer’s Disease International (2015).

United Nations DoEaSA. Population Division: World Population Ageing, 2019: Highlights (United Nations DoEaSA, 2019).

Abyad, A. Ageing in the Middle-East and North Africa: Demographic and health trends. Int. J. Ageing Dev. Countries 6(2), 112–128 (2021).

Boutayeb, A. The burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases in developing countries. In Handbook of Disease Burdens and Quality of Life Measures (2010).

Arezki, R.M.-D. et al. Trading Together: Reviving Middle East and North Africa Regional Integration in the Post-Covid Era (World Bank, 2020).

World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases Country Profiles 2018 (World Health Organization, 2018).

Brown, E. E., Kumar, S., Rajji, T. K., Pollock, B. G. & Mulsant, B. H. Anticipating and mitigating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 28(7), 712–721 (2020).

Sabetkish, N. & Rahmani, A. The overall impact of COVID-19 on healthcare during the pandemic: A multidisciplinary point of view. Health Sci. Rep. 4(4), e386 (2021).

Suárez-González, A., Rajagopalan, J., Livingston, G. & Alladi, S. The effect of COVID-19 isolation measures on the cognition and mental health of people living with dementia: A rapid systematic review of one year of quantitative evidence. EClinicalMedicine 39, 101047 (2021).

Mohamed, S., Rosenheck, R., Lyketsos, C. G. & Schneider, L. S. Caregiver burden in Alzheimer disease: Cross-sectional and longitudinal patient correlates. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 18(10), 917–927 (2010).

Burns, A. The burden of Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 3(7), 31–38 (2000).

Skaria, A. P. The economic and societal burden of Alzheimer disease: Managed care considerations. Am. J. Manag. Care 28(10 Suppl), S188-s196 (2022).

Aranda, M. P. et al. Impact of dementia: Health disparities, population trends, care interventions, and economic costs. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 69(7), 1774–1783 (2021).

Velandia, P. P. et al. Global and regional spending on dementia care from 2000–2019 and expected future health spending scenarios from 2020–2050: An economic modelling exercise. EClinicalMedicine 45, 101337 (2022).

Tham, T. Y. et al. Integrated health care systems in Asia: An urgent necessity. Clin. Interv. Aging 13, 2527–2538 (2018).

Blasi, Z. V., Hurley, A. C. & Volicer, L. End-of-life care in dementia: A review of problems, prospects, and solutions in practice. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 3(2), 57–65 (2002).

El-Metwally, A. et al. Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia in Arab countries: A systematic review. Behav. Neurol. 2019, 3935943 (2019).

Weidner, W. & Barbarino, P. The state of the art of dementia research: New frontiers. Alzheimer Dement. 15, P1473 (2019).

Katoue, M. G., Cerda, A. A., García, L. Y. & Jakovljevic, M. Healthcare system development in the Middle East and North Africa region: Challenges, endeavors and prospective opportunities. Front Public Health 10, 1045739 (2022).

Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet (2024).

Steinmetz, J. D. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of disorders affecting the nervous system, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Neurol. 23(4), 344–381 (2024).

Collaborators, G. et al. Global mortality from dementia: Application of a new method and results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Alzheimer Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 7(1), e12200 (2021).

Amini, M., Zayeri, F. & Moghaddam, S. S. Years lived with disability due to Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in Asian and north African countries: A trend analysis. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 9(1), 29–35 (2019).

Li, X. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, 1990–2019. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 937486 (2022).

Nichols, E. & Vos, T. The estimation of the global prevalence of dementia from 1990–2019 and forecasted prevalence through 2050: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study 2019. Alzheimer Dement. 17, e051496 (2021).

Velandia, P. et al. Global and regional spending on dementia care from 2000–2019 and expected future health spending scenarios from 2020–2050: An economic modelling exercise. EClinicalMedicine 45, 101337 (2022).

Nichols, E. et al. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 7(2), e105–e125 (2022).

Mobaderi, T., Kazemnejad, A. & Salehi, M. Exploring the impacts of risk factors on mortality patterns of global Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias from 1990 to 2021. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 15583 (2024).

Reitsma, M. B. et al. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and attributable disease burden in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet 397(10292), 2337–2360 (2021).

Brauer, M. et al. Global burden and strength of evidence for 88 risk factors in 204 countries and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet 403(10440), 2162–2203 (2024).

Venkataraman, A., Kalk, N., Sewell, G., Ritchie, C. W. & Lingford-Hughes, A. Alcohol and Alzheimer’s disease—does alcohol dependence contribute to beta-amyloid deposition, neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease?. Alcohol Alcohol. 52(2), 151–158 (2017).

Loscalzo, J. et al. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine (Springer, 2022).

Shahbandi, A. et al. Burden of stroke in North Africa and Middle East, 1990 to 2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. BMC Neurol. 22(1), 279 (2022).

Dintica, C. S. & Yaffe, K. Epidemiology and risk factors for dementia. Psychiatr. Clin. 45(4), 677–689 (2022).

Polyzos, E., Kuck, S. & Abdulrahman, K. Demographic change and economic growth: The role of natural resources in the MENA region. Res. Econ. 76(1), 1–13 (2022).

Yüceşahin, M. M. & Tulga, A. Y. Demographic and social change in the Middle East and North Africa: Processes, spatial patterns, and outcomes. Popul. Horizons 14, 2 (2017).

Javaid, S. F., Giebel, C., Khan, M. A. & Hashim, M. J. Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias: Rising global burden and forecasted trends. F1000 Res. 10, 425 (2021).

Swargiary, K. Global Life Expectancy Trends: Influencing Factors, Disparities, and Policy Implications in 2024 (Writat, 2024).

Seifarth, J. E., McGowan, C. L. & Milne, K. J. Sex and life expectancy. Gender Med. 9(6), 390–401 (2012).

Power, M. C. et al. Combined neuropathological pathways account for age-related risk of dementia. Ann. Neurol. 84(1), 10–22 (2018).

Stern, Y. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 11(11), 1006–1012 (2012).

Farfel, J. M. et al. Very low levels of education and cognitive reserve: A clinicopathologic study. Neurology 81(7), 650–657 (2013).

Giacomucci, G. et al. Gender differences in cognitive reserve: Implication for subjective cognitive decline in women. Neurol. Sci. 2022, 1–10 (2022).

Wilson, R. S. et al. Education and cognitive reserve in old age. Neurology 92(10), e1041–e1050 (2019).

Le Carret, N. et al. Influence of education on the pattern of cognitive deterioration in AD patients: The cognitive reserve hypothesis. Brain Cogn. 57(2), 120–126 (2005).

Subramaniapillai, S., Almey, A., Rajah, M. N. & Einstein, G. Sex and gender differences in cognitive and brain reserve: Implications for Alzheimer’s disease in women. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 60, 100879 (2021).

Ward, D. D., Ranson, J. M., Wallace, L. M., Llewellyn, D. J. & Rockwood, K. Frailty, lifestyle, genetics and dementia risk. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 93(4), 343–350 (2022).

Lourida, I. et al. Association of lifestyle and genetic risk with incidence of dementia. Jama 322(5), 430–437 (2019).

Uddin, M. S. et al. APOE and Alzheimer’s disease: Evidence mounts that targeting APOE4 may combat Alzheimer’s pathogenesis. Mol. Neurobiol. 56(4), 2450–2465 (2019).

Zhong, N. & Weisgraber, K. H. Understanding the association of apolipoprotein E4 with Alzheimer disease: Clues from its structure. J. Biol. Chem. 284(10), 6027–6031 (2009).

Ungar, L., Altmann, A. & Greicius, M. D. Apolipoprotein E, gender, and Alzheimer’s disease: An overlooked, but potent and promising interaction. Brain Imaging Behav. 8, 262–273 (2014).

Subramaniapillai, S. et al. Group P-AR: Sex differences in brain aging among adults with family history of Alzheimer’s disease and APOE4 genetic risk. NeuroImage Clin. 30, 102620 (2021).

Mukadam, N. et al. Changes in prevalence and incidence of dementia and risk factors for dementia: An analysis from cohort studies. Lancet Public Health 9(7), e443–e460 (2024).

Ritchie, C. W. et al. The PREVENT Dementia programme: Baseline demographic, lifestyle, imaging and cognitive data from a midlife cohort study investigating risk factors for dementia. Brain Commun. 6(3), 1–10 (2024).

Bransby, L., Rosenich, E., Maruff, P. & Lim, Y. How modifiable are modifiable dementia risk factors? A framework for considering the modifiability of dementia risk factors. J. Prev. Alzheimer Dis. 11(1), 22–37 (2024).

Shah, H. et al. Research priorities to reduce the global burden of dementia by 2025. Lancet Neurol. 15(12), 1285–1294 (2016).

Bamford, S.-M. & Walker, T. Women and dementia: Not forgotten. Maturitas 73(2), 121–126 (2012).

Williams, F., Moghaddam, N., Ramsden, S. & De Boos, D. Interventions for reducing levels of burden amongst informal carers of persons with dementia in the community: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Aging Mental Health 23(12), 1629–1642 (2019).

Lisko, I. et al. How can dementia and disability be prevented in older adults: Where are we today and where are we going?. J. Internal Med. 289(6), 807–830 (2021).

Kyu, A. Collaborators GBD, & Nigatu, Y. Global burden of disease 1950–2021 and impact of COVID-19. Lancet (2024).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation staff and its collaborators who prepared these publicly available data. We would also like to thank the Clinical Research Development Unit of Tabriz Valiasr Hospital, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran for their assistance in this research.

Funding

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which had no involvement in the preparation of this manuscript, funded the GBD study. This report was funded by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Grant No. 43010066), with partial support from Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (Grant No. 75883).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SS and AAK designed the study. SS analysed the data and performed the statistical analyses. SS, FA, AS, AE, MJMS and AAK drafted the initial manuscript. All authors reviewed the drafted manuscript for critical content and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The present study was reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1403.067).

Data availability

The data used for these analyses are all publicly available at http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Amiri, F., Safiri, S., Shamekh, A. et al. Prevalence, deaths and disability-adjusted life years due to Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in Middle East and North Africa, 1990–2021. Sci Rep 15, 7058 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89899-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89899-w