Abstract

Current deep learning methods for diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) typically rely on analyzing all or parts of high-resolution 3D volumetric features, which demand expensive computational resources and powerful GPUs, particularly when using multimodal data. In contrast, lightweight cortical surface representations offer a more efficient approach for quantifying AD-related changes across different cortical regions, such as alterations in cortical structures, impaired glucose metabolism, and the deposition of pathological biomarkers like amyloid-\(\beta\) and tau. Despite these advantages, few studies have focused on diagnosing AD using multimodal surface-based data. This study pioneers a novel method that leverages multimodal, lightweight cortical surface features extracted from MRI and PET scans, providing an alternative to computationally intensive 3D volumetric features. Our model employs a middle-fusion approach with a cross-attention mechanism to efficiently integrate features from different modalities. Experimental evaluations on the ADNI series dataset, using T1-weighted MRI and \([^{18}\text {F}]\)Fluorodeoxyglucose PET, demonstrate that the proposed model outperforms volume-based methods in both early AD diagnosis accuracy and computational efficiency. The effectiveness of our model is further validated with the combination of T1-weighted MRI, A\(\beta\) PET, and Tau PET scans, yielding favorable results. Our findings highlight the potential of surface-based transformer models as a superior alternative to conventional volume-based approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a devastating neurodegenerative disorder characterized by progressive cognitive decline that affects numerous older adults worldwide1. Early detection of AD is crucial for timely intervention and improved patient outcomes2,3. Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) has been identified as a prodromal stage of AD, manifesting subtle cognitive deficits beyond normal age-related changes that do not significantly impair daily functions4. The MCI diagnosis plays a vital role in early AD detection, initiating appropriate management strategies and interventions3.

Various imaging techniques, including T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (T1w MRI), \([^{18}\text {F}]\)Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET), amyloid-\(\beta\) (A\(\beta\)) PET, and Tau PET, have been employed for AD diagnosis. T1w MRI provides insights into brain structure. FDG PET measures regional cerebral glucose metabolism and is valuable for assessing brain function and identifying areas of hypometabolism associated with AD5. A\(\beta\) PET and Tau PET scans are used to assess the deposition of pathological biomarkers linked to AD pathology6. The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) provides rich imaging datasets for AD research7. The ADNI1 dataset, which primarily consists of T1w MRI and FDG PET images, is widely used in studying different biomarkers and developing deep learning methods for AD. The ADNI2 and ADNI3 initiatives introduce A\(\beta\) and Tau PET, which aim to validate A\(\beta\) and tau proteins as AD biomarkers.

Recently, deep learning in neuroimaging has emerged as a leading technology for diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease. Existing deep learning methods for AD diagnosis typically rely on 3D volumetric features8,9,10,11. These volume-based approaches often utilize convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to extract features from entire T1-weighted MRI and PET images or from 3D patches. While these methods achieve state-of-the-art performance, they are computationally demanding and resource-intensive, particularly during training. This poses significant challenges in scenarios involving multimodal data, especially for smaller healthcare facilities with limited resources.

Flowchart for extracting cortical features. The T1w MRI scans were processed by FreeSurfer to generate the cortex surface representation, cortical parcellation, and structural features, including cortical thickness, sulcal depth, and curvature. The PET scans were processed by the PETSurfer tool, registering to T1w MRI using the registration matrix generated by FreeSurfer, calculating the standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR), performing partial volume correction (step not depicted in the figure), sampling onto cortical surfaces, and finally mapping onto the surface area of the new average subject (fsaverage). All features were resampled onto sixth-ordered icospheres, thereby extracting non-overlapping triangular patches.

Cortical surface representations provide detailed insight into cortical structure and enable precise localization of brain activity, offering advantages in neuroimaging studies12,13,14. These surface-based approaches also offer specific advantages in the diagnosis of AD: (1) The cortical surface provides a more accurate depiction of brain structure, capturing intricate folding patterns and gyri12. Because early AD stages often exhibit subtle region-specific atrophy, analyzing the cortical geometry and cortical thickness on the surface helps detect these changes effectively15,16. (2) Surface-based registration is superior to volume-based methods as it preserves the folding pattern of the cortex17,18. Traditional volume-based registration methods struggle to align surface geometry, potentially leading to the loss of crucial gray-matter atrophy patterns required for AD diagnosis19,20,21. Surface-based registration methods such as sphere registration12,22 or utilizing the Laplace-Beltrami embedding space23, rely on intrinsic cortical surface geometry, maintaining the integrity of gray-matter atrophy patterns.

Few studies have explored surface-based deep learning applications for AD diagnosis16,24,25. These approaches generally do not surpass the performance of volume-based methods, likely due to their reliance on a single modality or the use of graph convolutional neural networks (GCNNs). GCNNs often face challenges in learning features that are both rotationally equivariant and highly expressive, while also maintaining manageable computational costs. These limitations were highlighted in a recent benchmarking study by Fawaz et al.26, which evaluated geometric deep learning approaches in the context of cortical analysis. However, emerging evidence suggests that attention-based transformer models outperform CNNs by capturing long-range interactions and mitigating local feature biases27. Similarly, Dahan et al.28 demonstrated the superior performance of a vision transformer model compared to GCNNs in cortical surface analysis.

In summary, this study aims to fully leverage surface-based features for early AD diagnosis by proposing a novel multimodal surface-based transformer model. The key contributions of this work are threefold:

-

We explore the effectiveness of cortical surface features extracted from T1-weighted MRI and PET scans for AD diagnosis. Unlike previous surface-based studies that focus primarily on cortical structure, employing a single-modality approach, we incorporate cortical function derived from PET images to improve diagnostic accuracy, demonstrating the potential of a multimodal surface-based method for disease diagnosis.

-

To address the challenges of integrating multiple modalities, we designed a novel middle-fusion attention model. While transformer architectures have shown superior performance on volume-based data, we extend their application to surface-based representations. Specifically, we propose a special attention block, called the mix-transformer, with a cross-attention mechanism to analyze multimodal features and classify AD patients. This design fosters stronger interactions between modalities, enhancing classification performance.

-

We conducted experiments across the entire ADNI series, including the ADNI1, ADNI2, and ADNI3 datasets. Results from the ADNI1 dataset demonstrate that the proposed approach outperforms volume-based methods in early AD diagnosis while offering significantly improved computational efficiency during training. Similarly, favorable outcomes on the ADNI2 and ADNI3 datasets validate the effectiveness of the proposed model across different PET radiotracers.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. “Surface-based feature extraction” outlines the pipeline for surface-based feature extraction. The proposed multimodal transformer model architecture is detailed in “The proposed transformer model architecture”. In “Experiments”, we describe the ADNI datasets, experimental setup, and evaluation metrics. “Results” presents the experimental outcomes on the full ADNI dataset, comparing our model to volume-based methods and evaluating different multimodal fusion strategies. Lastly, “Discussion and conclusion” provides conclusions and main summaries.

The proposed middle-fusion attention model architecture begins by extracting patches from the icospheres, which are then flattened and embedded into a common dimensional space. In this architecture, the features derived from each PET imaging modality correspond to one of the channels (C) within the PET module, where C ranges from 1 to 2 depending on the number of PET radiotracers used. A self-attention mechanism is applied in the transformer block to capture dependencies within each modality. Next, the mix-transformer block performs modality fusion by employing cross-attention operations to capture relationships across modalities. The fused outputs are then concatenated and passed through a classifier to generate class probabilities.

Methods

Surface-based feature extraction

The processing pipeline was designed to extract cortical features from different modalities, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

For T1-weighted (T1w) MRI scans, we used FreeSurfer29 (version 7.3.2) for the automated segmentation and parcellation of the brain MRI data. The FreeSurfer processing pipeline comprises several steps. Initially, T1w MRI scans underwent intensity normalization, non-brain tissue removal, and spatial normalization to a common template. Subsequently, precise surface representations were generated by reconstructing the gray-white matter boundary. To facilitate cortical region analysis, the cortex was divided into distinct cortical regions using the Desikan-Killiany and Destrieux30 parcellation atlases. Finally, structural measurements of the cortex, including cortical thickness, sulcal depth, and curvature, were performed to capture the fine-grained cortical characteristics relevant to our analysis.

For the FDG-PET, A\(\beta\) PET (\([^{18}\text {F}]\)AV-45), and Tau PET (\([^{18}\text {F}]\)AV-1451) scans, we used the PETSurfer tool, an extension of the FreeSurfer software designed to process PET data13,14. The relevant features from each PET modality were extracted in several steps, as follows: First, the PET images were registered to the corresponding anatomical space to ensure spatial alignment with the T1w MRI scans. Next, partial volume correction was applied using the Müller–Gärtner method13,14, alleviating the blurring effects caused by the limited spatial resolution of PET imaging. To assess regional cerebral glucose metabolism from FDG PET scans, the standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) was computed using the cerebellar cortex as the reference region, which is commonly employed due to its stable glucose metabolism31. For A\(\beta\) PET and tau PET scans, SUVR values were computed with reference to the cerebellum32, which exhibits low A\(\beta\) or tau uptake33. SUVR provides a relative measure of uptake in target brain regions compared to the reference region, reflecting glucose metabolism in FDG PET and the deposition of A\(\beta\) or tau pathology in amyloid and tau PET scans. The SUVR from the FDG PET, A\(\beta\) PET, and Tau PET scans were then projected onto the cortical surface by sampling halfway between the white and pial surfaces. Finally, to enable group-level comparisons and analyses, the projected SUVR values were mapped to the template surface of FreeSurfer (fsaverage), providing a standardized representation of PET-derived cortical features across subjects.

To address the potential bottleneck of surface reconstruction using FreeSurfer, we implemented a multithreaded Python-based workflow that parallelizes key steps in the recon-all pipeline. This optimization significantly reduced the surface reconstruction time from the typical four to twelve hours per subject to approximately 30 minutes per subject, without omitting any critical steps of the pipeline. This efficiency improvement leverages modern computational resources and ensures accurate surface reconstruction while maintaining computational feasibility for larger datasets.

Using FreeSurfer and PETSurfer, we extracted comprehensive sets of cortical features from multiple modalities. These features included cortical thickness, sulcal depth, curvature, as well as PET-derived measures of cerebral glucose metabolism, A\(\beta\) deposition, and tau pathology, which served as crucial inputs for our model. This comprehensive set of features allowed us to capture diverse aspects of cortical changes associated with AD pathology and contributed to early AD diagnosis.

In this study, we addressed the potential impact of surface noise by incorporating noise injection during training. Gaussian noise was added directly to the input features in each forward pass, simulating variability in surface reconstructions. This method enabled the model to learn robust features without requiring explicit data augmentation techniques.

The proposed transformer model architecture

The architecture of the proposed middle-fusion multimodal model is shown in Fig. 2. The components of the model are described as follows:

Embedding

The input data were resampled onto a sixth-order icosphere with 40,962 vertices for computational efficiency using the Connectome Workbench (https://www.humanconnectome.org/software/connectome-workbench). Subsequently, the data were divided into non-overlapping triangular patches, resulting in a set of flattened patches. The left and right hemispheres were combined, resulting in 640 patches of 153 vertices each. To capture the spatial information within the model, a trainable linear layer was utilized in combination with a trainable positional embedding. This step facilitates the projection of the input sequence onto a lower-dimensional representation while incorporating essential spatial information.

Transformer block

The first stage consists of L transformer blocks arranged sequentially. Each transformer block comprises two main components: a multi-head self-attention (MHSA) layer and a multilayer perceptron (MLP). The MHSA layer enables the model to perform self-attention across sequences by capturing the important relationships and dependencies within the patches. The MLP component extracts high-level representations from the low-level outputs of the MHSA.

For each transformer block in layer l, the input sequence X(l) undergoes the following transformation:

To enhance the learning process, layer normalization34 was applied before each MHSA and MLP layer. This normalization technique aids in stabilizing the training process and accelerates convergence.

The MHSA layer captures important relationships and dependencies within the input sequence. By employing multiple self-attention operations in parallel, represented by each head, the MHSA layer allows the model to capture different types of attention patterns and extract diverse information from the input sequences. Each attention head attends to different parts of the input sequence and learns to assign weights to different elements based on relevance. This mechanism enables the model to capture long-range dependencies and interactions between the patches in the sequence. The outputs of the attention heads are concatenated using a linear layer, allowing the model to capture a comprehensive representation of the input sequence.

The MLP layer consists of three consecutive layers: an expansion-dense layer, a Gaussian error linear unit (GELU) activation function, and a contraction-dense layer. The dense expansion layer increases the dimensionality of the input sequence for a more expressive representation, whereby a linear transformation is applied to the input, followed by an element-wise activation function, GELU35. Following GELU activation, the contraction-dense layer reduces the dimensionality of the features to the desired output dimension. This sequence of expansion-dense GELU activation, along with contraction-dense layers in the MLP component, enables the model to learn and represent intricate relationships and patterns in the input sequence. Acting as nonlinear mapping, GELU activation extracts higher-level features from the lower-level representations obtained from the attention mechanism.

Mix-transformer

The mix-transformer block, shown in Fig. 2, employs a cross-attention mechanism to effectively handle complex interactions between different modalities. Provided with two inputs, \(X_1\) and \(X_2\), that represent distinct information from separate modalities, the mix-transformer performs cross-modality analysis through multi-head cross-attention. The following equations describe this process:

where

Here, \(\text {MHCA}(X_1, X_2)\) represents the multi-head cross-attention function, which is implemented by applying linear transformations to \(X_1\) and \(X_2\) to obtain query (Q) with the former and key (K) and value (V) matrices with the latter. The attention mechanism, \(\text {Attention}(Q, K, V)\), computes the attention scores between \(X_1\) and \(X_2\), to obtain inter-modality relationships. The output Z(l) represents the attended representation, which is combined with the input \(X_1\) through element-wise addition, to incorporate cross-modality information.

Classifier

The outputs of the mix-transformer blocks were flattened, concatenated, and linearly transformed using a fully connected layer. Finally, a simple logistic classifier with sigmoid activation was used to produce the output class probabilities. The model was trained using the Binary Cross-Entropy Loss to optimize the classification performance.

Multimodal fusion strategies

In designing the multimodal model, we considered three fusion strategies: Early-fusion, Late-fusion, and Middle-fusion.

The Early-fusion model combines raw modality data at the earliest stage of processing. Typically, fusion is achieved by combining input features channel-wise. The main advantages of this approach are:

-

It simplifies the processing pipeline.

-

It consumes only half the computational resources compared to two-branch models like Late-fusion or Middle-fusion.

-

It enables the model to learn inter-modality relationships.

However, Early-fusion diminishes the discriminative power of each modality. By combining raw modality data, the model is unable to learn modality-specific nuances. Additionally, integrating raw data from diverse modalities can be challenging.

In contrast, the Late-fusion model combines the outputs from each independent information processing stream. Each stream processes its data separately, and the results are fused at the output. While this approach allows the model to learn modality-specific features, its ability to capture inter-modality relationships is limited.

To overcome the limitations of the two designs mentioned above, we employ the Middle-fusion architecture. The proposed design (as shown in Fig. 2) consists of two stages. The first stage performs modality-specific feature extraction using a self-attention mechanism, which captures long-range interactions and dependencies between distinct regions of the cortex. The resulting modality-specific features are then fed into the second stage, where inter-modality analysis takes place. This stage uses a cross-attention mechanism to align features from each modality into a common space, enabling the model to learn complementary information across modalities.

Experiments

Datasets

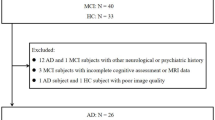

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). The ADNI was launched in 2003 as a public-private partnership, led by Principal Investigator Michael W. Weiner, MD. The primary goal of ADNI has been to test whether serial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET), other biological markers, and clinical and neuropsychological assessments can be combined to measure the progression of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and early Alzheimer’s disease (AD). We collected data for the entire ADNI series, including ADNI1, ADNI2, and ADNI3, in February 2022. Specifically, baseline FDG PET scans were acquired for ADNI1, and baseline A\(\beta\) and Tau PET scans for ADNI2 &3, along with T1w MRI scans acquired less than two months before the PET scans for every subject. The PET scans used in this study were preprocessed prior to acquisition, including co-registration with the baseline FDG PET scans, averaging over six five-minute frames, and standardization to a uniform resolution. To ensure the reliability of the diagnoses, the data were collected according to the following subject selection criteria:

-

CN: Subjects diagnosed as cognitively normal at baseline and remained stable during follow-up checkups.

-

MCI: Subjects diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment at baseline, including those who remained stable or progressed to AD during the follow-up period.

-

AD: Subjects diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease at baseline and remained stable during follow-up checkups.

The demographic information for the collected datasets is summarized in Table 1.

Experimental setting

A lightweight attention model with specific configurations was employed to ensure compatibility with a wide range of computing resources. The model consists of three transformer layers, three mix-transformer layers, three attention heads (for MHSA and MHCA), and a hidden layer of dimension 192.

To prevent overfitting, a dropout layer was incorporated after each transformer layer with a dropout probability of 0.1. The model was trained using the Adam optimizer and a binary cross-entropy loss function, starting with an initial learning rate of 1 x \(10^{-3}\) which was gradually decreased to a minimum learning rate of 1 x \(10^{-5}\) following the one-cycle cosine-learning rate schedule. The training process spanned 50 epochs with a batch size of eight.

To ensure reproducibility, the random number generator in Python was used to set the seed. All the experiments were conducted using the TensorFlow framework on an Intel Xeon W-2265 CPU and GeForce RTX 2080ti.

In following this experimental setup, the aim was to obtain reliable and comparable results considering computational efficiency and reproducibility.

Evaluation scheme

The proposed model was evaluated on two binary classification tasks: AD diagnosis (CN vs. AD) and early AD diagnosis (CN vs. MCI). To evaluate the performance of the proposed model, a stratified five-fold cross-validation approach was employed. In stratified five-fold cross-validation, the dataset is divided into five subsets, ensuring each subset maintains the same class distribution. Four subsets are used for training, and the remaining subset for validation, repeated five times. The average out-of-fold (OOF) validation results are then computed to assess the model’s performance comprehensively across different data splits.

Given the unbalanced nature of the dataset, several evaluation metrics were considered to accurately assess the performance of the classification tasks. These metrics included:

Balanced accuracy: Considering class imbalance, balanced accuracy measures the average accuracy of the model across both classes. The formula for balanced accuracy is,

Sensitivity: Also known as the true positive rate or recall, sensitivity measures the proportion of correctly classified positive samples (e.g., AD or MCI) out of all actual positive samples. The formula for sensitivity is as follows:

Specificity: This measures the proportion of correctly classified negative samples (e.g., CN) out of all actual negative samples. The formula for specificity is as follows:

Area under the ROC curve (AUC): AUC quantifies the ability of the model to discriminate between positive and negative samples across various classification thresholds. A higher AUC indicates better classification performance. AUC is computed by plotting the true positive rate (sensitivity) against the false positive rate (1 - specificity) and calculating the area under the resulting curve.

Results

Fusion strategies

We validate the effectiveness of our proposed Middle-fusion strategy to Early-Fusion, where MRI and PET features are concatenated channel-wise at the input, and Late-Fusion, where fusion occurs just before the fully connected (FC) layer. The number of transformer blocks was set to six in all models to maintain consistency with the middle-fusion model. The results, presented in Table 2, show significant improvements with the proposed middle-fusion model compared to the common fusion strategies across all tasks and datasets. Due to this observation, we adopted the middle-fusion strategy for all multimodal approaches in this study. Consequently, the results of our multimodal methods presented in other tables also reflect the use of this strategy.

Results on the ADNI1 dataset

In this section, we present the results of experiments conducted on the ADNI1 dataset, focusing on the comparison between unimodal and multimodal approaches. For the unimodal architectures, only one modality was used in each experiment, with the extracted features subsequently fed into the classifier for final prediction. Table 3 summarizes the performance metrics obtained from these evaluations.

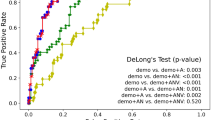

In the AD diagnosis task, the results clearly show that the multimodal approach outperforms the unimodal methods. The multimodal combination achieved a balanced accuracy of \({0.962} \pm {0.012}\) and an AUC of \({0.969} \pm {0.031}\). Notably, the improvements are even more significant in the early AD diagnosis task, where the model attained 79% balanced accuracy and an 81% AUC. Specifically, to assess the statistical significance of the differences between input methods, we performed a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey HSD post-hoc tests on the results obtained from five-fold cross-validation. For BACC, the ANOVA revealed a significant difference between the groups (F-statistic = 9.22, p-value = 0.004). Post-hoc analysis showed that FDG performs significantly better than MRI (p-adj = 0.045), and MRI+FDG significantly outperforms MRI (p-adj = 0.003). No significant difference was observed between FDG and MRI+FDG (p-adj = 0.323). For AUC, the ANOVA also revealed a significant difference between the groups (F-statistic = 8.12, p-value = 0.006). Further analysis showed that MRI+FDG significantly outperforms MRI (p-adj = 0.004), but no significant differences were observed between FDG and MRI (p-adj = 0.142) or FDG and MRI+FDG (p-adj = 0.160). These results collectively demonstrate that MRI+FDG provides the best performance across metrics, significantly outperforming MRI alone and being statistically comparable to FDG in most cases. This highlights that our proposed model effectively leverages complementary information from each modality, forming a stronger multimodal representation and addressing the limitations of multimodal data integration in conventional volume-based methods.

Results on the ADNI2 & ADNI3 datasets

To further assess the effectiveness of the proposed model across PET radiotracers, we conducted additional experiments on the ADNI2 and ADNI3 datasets, as shown in Table 4.

For the AD diagnosis task, the model achieved the best performance when using all three modalities (MRI, A\(\beta\), and Tau), with a balanced accuracy of \({0.94} \pm {0.04}\), sensitivity of \({0.91} \pm {0.06}\), specificity of \({0.97} \pm {0.03}\), and an AUC of \({0.95} \pm {0.03}\). Similarly, for the early AD diagnosis task, the combination of all three modalities resulted in the highest performance, with a balanced accuracy of \({0.75} \pm {0.04}\), sensitivity of \({0.72} \pm {0.05}\), specificity of \({0.79} \pm {0.05}\), and an AUC of \({0.79} \pm {0.03}\).

To evaluate the statistical significance of the differences between input methods in the early AD diagnosis task, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey HSD post-hoc tests were performed on the results from five-fold cross-validation for both BACC and AUC metrics. For BACC, the ANOVA revealed a significant difference between the groups (F-statistic = 6.09, p-value = 0.006). Post-hoc analysis showed that Amyloid+Tau+MRI significantly outperforms MRI (p-adj = 0.005). No significant differences were observed between Amyloid+Tau+MRI and Amyloid (p-adj = 0.413) or Tau (p-adj = 0.842). For AUC, the ANOVA also revealed a significant difference between the groups (F-statistic = 3.62, p-value = 0.036). Post-hoc analysis showed that Amyloid+Tau+MRI significantly outperforms MRI (p-adj = 0.035), but no significant differences were observed between Amyloid+Tau+MRI and Amyloid (p-adj = 0.666) or Tau (p-adj = 0.975). These findings indicate that while the combination of MRI + Amyloid + Tau significantly improves performance compared to MRI, its performance is statistically comparable to Amyloid and Tau for both BACC and AUC.

The results on the ADNI2 and ADNI3 datasets are consistent with those on the ADNI1 dataset, as shown in Table 3. This confirms the effectiveness of the proposed model across the entire ADNI series and strengthens the importance of the proposed multimodal approach in early AD diagnosis.

Comparisons to other methods

In this section, we compare our results with other methods on the ADNI dataset. Table 5 summarizes the performance comparisons of the various methods for AD diagnosis (CN vs. AD) and early AD diagnosis (CN vs. MCI). The metrics considered for the evaluation were balanced accuracy (BACC), sensitivity (SEN), specificity (SPE), and area under the ROC curve (AUC).

For AD diagnosis, the proposed method demonstrated competitive performance compared with the top-performing method, yielding a balanced accuracy of 0.962, sensitivity of 0.976, specificity of 0.948, and AUC of 0.969. Although the proposed method achieved competitive performance with respect to the best-performing volume-based method10 in terms of BACC, it is worth noting that our input size was 13 times smaller. This means that the proposed model can save a large amount of computing resources while still achieving competitive performance.

In the early AD diagnosis task, the proposed method demonstrated superior performance, with a balanced accuracy of 0.788 and AUC of 0.805. This method outperformed volume-based methods in terms of balanced accuracy and AUC by a considerable margin. The advantage of the proposed approach stems from the fewer parameters, smaller input size, and superior inference time compared with the lightweight 3D CNN (see Table 6). Although the acquisition time for surface representation is longer than that for volumetric data, it only needs to be performed once during the training phase. In practice, most studies require multiple training iterations due to hyperparameter tuning and architecture modifications. Thus, our approach significantly reduces training time while ensuring high accuracy during inference. This underscores the superiority of our proposed model in both diagnostic performance and computational efficiency.

Furthermore, to evaluate the performance of the proposed transformer-based model, we included two additional graph-based methods, Zhang et al.25 and Wee et al.16, in our comparisons presented in Table 5. Both methods employ GCNs for cortical surface analysis. Our results demonstrate that the proposed method outperforms these GCN-based approaches in most metrics by substantial margins.

Discussion and conclusion

In this study, a novel multimodal surface-based transformer model is proposed for the early diagnosis of AD, using a combination of T1-weighted MRI and PET scans. The model first analyzes each modality independently and then fuses these modalities using cross-attention. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed model outperforms volume-based approaches in early AD diagnosis across various PET radiotracers. We argue that several factors contribute to the excellent performance: (1) To effectively integrate multimodal features, FDG PET was first registered to T1w MRI or a common template to address differences in spatial resolution and head positioning. After registration, PET SUVR was mapped onto the cortical surface using surface representation, which reduces noise and partial volume effects while aligning PET signals to cortical structures. This process enables the extraction of robust multimodal features for analysis. (2) Cortical representation allows the measurement of cortical structure and function; nevertheless, using pixel-intensity information is much more challenging. (3) The design of the proposed middle-fusion attention model effectively leverages complementary multimodal information, as indicated by the significant improvements in Tables 3, 4, and 2.

FDG PET is well-established as a tool for capturing metabolic changes indicative of glucose hypometabolism, particularly in regions affected by early AD, such as the temporoparietal cortex and posterior cingulate5,38. Similarly, amyloid and tau PET are widely recognized for reflecting hallmark pathological features, such as amyloid plaque deposition and tau neurofibrillary tangles39,40. Building upon these established principles, our study demonstrates how these modalities, when integrated with structural MRI via the middle-fusion transformer model, contribute complementary strengths to enhance diagnostic performance. Specifically, this integration leverages the metabolic, pathological, and structural information provided by these modalities, achieving improved diagnostic accuracy for early AD detection, as evidenced by the results in Tables 3 and 4. This comprehensive approach highlights the potential clinical utility of multimodal frameworks in supporting robust and generalizable AD diagnostics.

In addition, the superior performance of our method over other graph-based methods on surface data can be attributed to the integration of multimodal data (MRI and FDG PET), which captures complementary structural and functional information, as well as the advantages of the transformer architecture. Unlike GCNs, which rely on local connectivity, the global attention mechanism in our model enables it to capture long-range dependencies across the cortical surface. These results, as shown in Table 5, demonstrate the effectiveness of our approach in leveraging multimodal data for early AD diagnosis.

This study, however, is subject to several limitations. First, while cortical surface features accelerate and reduce computational resource requirements for the training process, the reconstruction process using FreeSurfer, even with the multi-threaded optimization described earlier, still takes approximately 30 minutes per subject, which remains time-consuming. As a future direction, integrating deep learning-based surface reconstruction methods41,42, into our pipeline could significantly reduce preprocessing time to just a few seconds while maintaining high accuracy. This improvement would address the time constraints of current approaches and enhance the scalability and clinical applicability of our method. Besides, the accuracy of surface mapping to fsaverage, as mentioned in “Surface-based feature extraction”, can be further improved by using state-of-the-art methods23,43,44.

Second, while visual inspection of the reconstructed cortical surfaces was performed to ensure overall quality, no explicit quality assurance metrics or manual corrections were applied in this study. As a result, segmentation inaccuracies or reconstruction artifacts may still exist within the dataset and could potentially affect performance. Such errors may introduce variability in the cortical surface representations, particularly in regions critical for AD pathology, such as the transentorhinal and posterior cingulate cortices, thereby impacting feature extraction and classification accuracy. Future work will involve systematically evaluating the impact of reconstruction errors through synthetic noise experiments or alternative surface reconstruction pipelines to further improve model robustness.

Finally, it is important to note that the subjects in this study were classified based on clinical diagnoses (CN, MCI, and AD) and the stability of these diagnoses during the 36-month follow-up period, rather than directly based on pathological hallmarks of AD. This approach reflects the clinical relevance of early AD detection, while future work could explore classifications that integrate both clinical and pathological markers for a more comprehensive understanding of disease progression.

The training and validation curves for loss, BACC, and AUC for ADNI1 and ADNI2 &3 across both tasks are presented in Supplementary Figures S1-S4. Notably, these results exhibit an intriguing pattern in early AD diagnosis task: while training loss decreases, validation loss increases. Despite this, performance metrics such as BACC and AUC continue to improve. This pattern likely reflects adjustments in the classification decision boundaries, where reduced confidence in some correct predictions is counterbalanced by improved predictions near the boundary. Such behavior may stem from the limited size of the ADNI dataset, which amplifies the challenges of training Transformer-based models that typically require larger datasets due to their lack of inductive biases found in convolutional architectures45. These challenges are further exacerbated in early AD diagnosis, a task characterized by subtle and often ambiguous distinctions between classes. Importantly, this highlights the need for a comprehensive learning strategy that considers all learning curves together to better understand and optimize model performance, particularly under conditions of data scarcity.

Partial volume correction (PVC) was considered in this study to address signal mixing due to the limited spatial resolution of PET imaging, particularly in small or atrophied regions such as the transentorhinal cortex. Without PVC, PET signals may be underestimated in small structures due to spill-out effects and overestimated in adjacent larger regions due to spill-in effects46. However, PVC is not always necessary, as it introduces assumptions that may not hold in all cases and can be sensitive to segmentation errors. Voxel-based methods, such as the Müller-Gärtner (MG) method47, operate at the voxel level and provide detailed corrections. However, their localized nature may amplify noise, particularly in regions with low signal-to-noise ratio13,48. In contrast, region-based methods, such as the geometric transfer matrix (GTM) method46 and region-based voxel-wise (RBV) correction49, provide smoother corrections across predefined anatomical regions, reducing noise but relying heavily on segmentation accuracy50. PVC methods vary in their approach: voxel-based methods like MG primarily correct for tissue fraction effects by estimating gray matter (GM) contribution within a voxel, while region-based methods like GTM focus on compensating for the limited spatial resolution of PET imaging. Some methods, such as the RBV approach, aim to correct for both factors simultaneously50. The choice of applying PVC should depend on study objectives, as uncorrected PET data may still be valid in certain contexts, particularly when avoiding potential biases introduced by correction algorithms.

The absence of traditional data augmentation techniques in this study reflects the unique challenges posed by brain surface-based data. Since the input data is represented as vertices and their associated features, conventional augmentation methods such as rotations or flips are not directly applicable as they could disrupt the spatial alignment of the cortical surface. Although Gaussian noise injection was incorporated during training to simulate surface variability and improve model generalization, future work could explore advanced augmentation strategies tailored to surface-based data to further enhance model robustness and performance.

The proposed method leverages cortical surface-based features derived from FDG PET, amyloid PET, and tau PET to capture regional biomarker distributions. However, 3D volumetric features retain complementary information about subcortical and global biomarker patterns that are not fully captured by cortical projections. Combining surface-based and volumetric features has the potential to enhance diagnostic robustness by leveraging complementary modalities. Future studies could explore a multimodal deep learning framework to integrate these features, allowing the model to capture both cortical and subcortical AD pathology, improving diagnostic sensitivity and generalizability across diverse datasets.

While this study focuses on binary classification tasks (CN vs. MCI and CN vs. AD), which are aligned with widely used methods in prior research and current clinical practice, this constitutes a limitation. Binary classification enables focused evaluation of key diagnostic challenges, such as distinguishing cognitively normal individuals from those with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease. This approach simplifies the task and enhances comparability with existing studies. However, adopting a multi-class classification could offer deeper insights by simultaneously examining the nuances among CN, MCI, and AD groups, thereby providing a more comprehensive evaluation of the diagnostic capabilities of the model. Future work will explore this paradigm, potentially incorporating advanced machine learning techniques to address the increased complexity and enhance the clinical utility of our method.

In conclusion, this study explored the potential of surface-based attention modeling as an alternative to volume-based approaches for early AD diagnosis. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to design a multimodal surface-based middle-fusion transformer model. Future research could focus on applying the proposed model to other neurodegenerative diseases. Given that surface-based features are generally lightweight and offer several advantages, this approach could also be applied to longitudinal data to monitor changes in the cerebral cortex, track disease progression, and assess the efficacy of interventions.

Data availibility

The ADNI dataset generated during and/or analysed during the current study is available at http://adni.loni.usc.edu/. The multithreaded Python-based workflow developed to parallelize FreeSurfer’s recon-all pipeline is available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Association, A. et al. 2017 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dementia 13, 325–373 (2017).

Borson, S. et al. Improving dementia care: The role of screening and detection of cognitive impairment. Alzheimer’s Dementia 9, 151–159 (2013).

Crous-Bou, M., Minguillón, C., Gramunt, N. & Molinuevo, J. L. Alzheimer’s disease prevention: From risk factors to early intervention. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 9, 1–9 (2017).

Gauthier, S. et al. Mild cognitive impairment. Lancet 367, 1262–1270 (2006).

Silverman, D. H. Brain \(^{18}\)F-FDG PET in the diagnosis of neurodegenerative dementias: Comparison with perfusion SPECT and with clinical evaluations lacking nuclear imaging. J. Nucl. Med. 45, 594–607 (2004).

Schroeter, M. L. et al. Amyloid and tau positron emission tomography as biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 14, 547–560 (2018).

Mueller, S. G. et al. The Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative. Clin. Neuropsychol. 15, 869–877 (2005).

Li, F. et al. Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis based on multiple cluster dense convolutional networks. Computer. Med. Imaging Graph. 70, 101–110 (2018).

Cui, R. & Liu, M. Hippocampus analysis by combination of 3-D DenseNet and Shapes for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 23, 2099–2107. https://doi.org/10.1109/JBHI.2018.2882392 (2019).

Zhang, J. et al. Multi-scale discriminative regions analysis in FDG-PET imaging for early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neural Eng. 19, 046030 (2022).

Liu, M. et al. A multi-model deep convolutional neural network for automatic hippocampus segmentation and classification in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage 208, 116459 (2020).

Dale, A. M., Fischl, B. & Sereno, M. I. Cortical surface-based analysis I: Segmentation and surface reconstruction. NeuroImage 9, 179–194 (1999).

Greve, D. N. et al. Cortical surface-based analysis reduces bias and variance in kinetic modeling of brain PET data. Neuroimage 92, 225–236 (2014).

Greve, D. N. et al. Different partial volume correction methods lead to different conclusions: An \(^{18}\)F-FDG-PET study of aging. Neuroimage 132, 334–343 (2016).

Querbes, O. et al. Early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease using cortical thickness: Impact of cognitive reserve. Brain 132, 2036–2047 (2009).

Wee, C.-Y. et al. Cortical graph neural network for AD and MCI diagnosis and transfer learning across populations. NeuroImage Clin. 23, 101929 (2019).

Das, S. R., Avants, B. B., Grossman, M. & Gee, J. C. Registration based cortical thickness measurement. Neuroimage 45, 867–879 (2009).

Van Essen, D. C. Surface-based approaches to spatial localization and registration in primate cerebral cortex. Neuroimage 23, S97–S107 (2004).

Thompson, P. M. et al. Mapping hippocampal and ventricular change in Alzheimer disease. Neuroimage 22, 1754–1766 (2004).

Vercauteren, T., Pennec, X., Perchant, A. & Ayache, N. Diffeomorphic demons: Efficient non-parametric image registration. NeuroImage 45, S61–S72 (2009).

Beg, M. F., Miller, M. I., Trouvé, A. & Younes, L. Computing large deformation metric mappings via geodesic flows of diffeomorphisms. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 61, 139–157 (2005).

Yeo, B. T. et al. Spherical demons: Fast diffeomorphic landmark-free surface registration. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 29, 650–668 (2009).

Gahm, J. K. et al. Riemannian metric optimization on surfaces (RMOS) for intrinsic brain mapping in the Laplace–Beltrami embedding space. Med. Image Anal. 46, 189–201 (2018).

Song, T.-A. et al. Graph convolutional neural networks for Alzheimer’s disease classification. In 2019 IEEE 16th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI 2019). 414–417 (IEEE, 2019).

Zhang, J. et al. Multi-relation graph convolutional network for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis using structural MRI. Knowl.-Based Syst. 270, 110546 (2023).

Fawaz, A. et al. Benchmarking geometric deep learning for cortical segmentation and neurodevelopmental phenotype prediction. bioRxiv 2021-12 (2021).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. 6000–6010 (2017).

Dahan, S. et al. Surface vision transformers: Attention-based modelling applied to cortical analysis. In International Conference on Medical Imaging with Deep Learning. 282–303 (PMLR, 2022).

Fischl, B. & Dale, A. M. FreeSurfer. NeuroImage 62, 774–781 (2012).

Destrieux, C., Fischl, B. & Dale, A. M. Automatic parcellation of the human cerebral cortex. Front. Neuroinform. 4, 7 (2010).

Nugent, S. et al. Selection of the optimal intensity normalization region for FDG-PET studies of normal aging and Azheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 10, 9261 (2020).

Vemuri, P. & Jack, C. R. Role of structural MRI in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2, 1–10 (2010).

Wong, D. F. et al. In vivo imaging of amyloid deposition in Alzheimer disease using the radioligand \([^{18}\text{ F}]\)-AV-45 (flobetapir F 18). J. Nucl. Med. 51, 913–920 (2010).

Ba, J. L., Kiros, J. R. & Hinton, G. E. Layer normalization. arXiv preprint[SPACE]arXiv:1607.06450 (2016).

Hendrycks, D. & Gimpel, K. Gaussian error linear units (GELUs). arXiv preprint[SPACE]arXiv:1606.08415 (2016).

Qiu, Z. et al. 3D multimodal fusion network with disease-induced joint learning for early Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. In IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging (2024).

Chen, Z. et al. Orthogonal latent space learning with feature weighting and graph learning for multimodal Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. Medical Image Anal. 84, 102698 (2023).

Chételat, G. et al. Amyloid-PET and \(^{18}\)F-FDG-PET in the diagnostic investigation of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Lancet Neurol. 19, 951–962 (2020).

Braak, H. & Braak, E. Neuropathological staging of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 82, 239–259 (1991).

Jack, C. R. Jr. et al. NIA-AA research framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dementia 14, 535–562 (2018).

Cruz, R. S. et al. Deepcsr: A 3D deep learning approach for cortical surface reconstruction. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision. 806–815 (2021).

Gopinath, K., Desrosiers, C. & Lombaert, H. Segrecon: Learning joint brain surface reconstruction and segmentation from images. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2021: 24th International Conference, Strasbourg, France, September 27–October 1, 2021, Proceedings, Part VII 24. 650–659 (Springer, 2021).

Zhao, F., Wu, Z., Wang, L., Lin, W. & Li, G. Fast spherical mapping of cortical surface meshes using deep unsupervised learning. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. 163–173 (Springer, 2022).

Jo, J. W. & Gahm, J. K. G-RMOS: GPU-accelerated Riemannian metric optimization on surfaces. Comput. Biol. Med. 150, 106167 (2022).

Zhou, H.-Y., Lu, C., Chen, C., Yang, S. & Yu, Y. A unified visual information preservation framework for self-supervised pre-training in medical image analysis. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 45, 8020–8035 (2023).

Rousset, O. G., Ma, Y. & Evans, A. C. Correction for partial volume effects in PET: Principle and validation. J. Nucl. Med. 39, 904–911 (1998).

Müller-Gärtner, H. W. et al. Measurement of radiotracer concentration in brain gray matter using positron emission tomography: MRI-based correction for partial volume effects. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 12, 571–583 (1992).

Sattarivand, M. et al. Region-based partial volume correction techniques for PET imaging: Sinogram implementation and robustness. Int. J. Mol. Imaging 2013, 435959 (2013).

Thomas, B. A. et al. The importance of appropriate partial volume correction for PET quantification in Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 38, 1104–1119 (2011).

Quarantelli, M. et al. Integrated software for the analysis of brain PET/SPECT studies with partial-volume-effect correction. J. Nucl. Med. 45, 192–201 (2004).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by an Institute of Information & communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korean Government (MSIT; IITP-2025-RS-2023-00254177, IITP-2025-RS-2024-00360227) and by the National Research Foundation of Korea(NRF) grant funded by the Korea government(MSIT; NRF-2020R1C1C1008362, 2022R1A4A1030189). Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California. Data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.K.G. and Q.A.D. devised the methods and designed the experiments, Q.A.D. and S.D.T. conducted the experiment(s), J.K.G. and Q.A.D. analyzed the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Duong, Q.A., Tran, S.D. & Gahm, J.K. Multimodal surface-based transformer model for early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep 15, 5787 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90115-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90115-y