Abstract

In order to detect epileptic spikes, this paper suggests a deep learning architecture that blends 1D residual convolutional neural networks (1D-ResCNN) with a hybrid optimization strategy. The Layer-wise Adaptive Moments (LAMB) and AdamW algorithms have been used in the model’s optimization to improve efficiency and accelerate convergence while extracting features from time and frequency domain EEG data. The framework has been considered on two public epilepsy datasets CHB-MIT and Siena. In the CHB-MIT dataset, comprising 24-channel EEG recordings from 12 patients, the model achieved an accuracy of 99.71%, a sensitivity of 99.60%, and a specificity of 99.61% for detecting epileptic spikes. Similarly, in the Siena dataset, which includes EEG data from 14 adult patients, the model demonstrated an average accuracy of 99.75%. Sensitivity averaged 99.94%, while specificity averaged 99.95%. The false positive rate (FPR) remained low at 0.0011, and the model obtained an average F1-score of 99.74%. For real-time hardware validation, the 1D-ResCNN model was deployed within the Typhoon HIL simulator, utilizing embedded C2000 microcontrollers. This hardware configuration allowed for immediate spike detection with minimal latency, ensuring reliable performance in real-time clinical applications. The findings imply that the suggested approach provides suitable for identifying epileptic spikes in real time for medical settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Epilepsy refers to a collection of disorders marked by the abnormal and excessive electrical activity within nerve cells1. It impacts a large number of individuals globally, with approximately 50 million people affected, predominantly in developing nations2. Sadly, although 70% of cases can be treated with medicine or electrical stimulation, 75% of affected individuals lack access to adequate therapy3. Epileptic seizures, resulting from unpredictable and poorly understood electrical disturbances in the brain, can occur in about one in every hundred individuals. A prompt and precise diagnosis is crucial for effectively managing and mitigating seizure risks. Recurrent episodes of brief unconsciousness are a feature of epilepsy, the second most common brain-related health problem globally4.

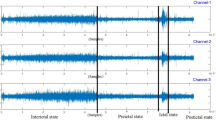

The EEG is frequently employed to evaluate brain activities and identify epileptic discharges, playing a crucial part in diagnosing epilepsy. Computer-based digital extraction of EEG signal parameters is highly beneficial to automate the diagnosis process. EEG technology has become widely used because it makes it possible to digitally record electrical signals of the brain, making it a popular tool for diagnosing epilepsy.Electrodes for electroencephalography (EEG) are applied to the scalp to capture neural activity. Manually diagnosing seizures by a neurologist is time-consuming and costly, as they carefully examine EEG data to detect pre-ictal, ictal, and inter-ictal patterns. The automated system speeds up diagnosis and enhances efficiency by detecting ictal patterns in EEG signals5. Epileptic spikes, which are transient abnormalities in EEG signals, serve as critical biomarkers for epilepsy diagnosis and monitoring. These spikes manifest differently across the various phases of epileptic activity. During the pre-ictal phase, spikes indicate the brain’s transitioning state toward seizure onset, providing crucial information for early warning systems and enabling timely intervention6. In the ictal phase, heightened abnormal electrical activity is observed, with spikes becoming more frequent and pronounced, aiding in confirming seizure events and understanding their progression7. The post-ictal phase often involves spikes reflecting residual neuronal hyperactivity and recovery processes following a seizure, which can be analyzed to assess the seizure’s impact on the brain8.In the inter-ictal phase, spikes observed between seizures act as key diagnostic markers for epilepsy, with their frequency, morphology, and distribution helping to differentiate epileptic patients from healthy individuals and localize seizure foci9. The temporal patterns, frequency, and amplitude of spikes during these phases are instrumental in epilepsy diagnosis, offering vital insights into the detection, classification, and prediction of epileptic events. As noted by10, the automatic recognition of seizures and spikes in EEG plays a pivotal role in advancing diagnostic accuracy while reducing the burden of manual analysis. This study focuses on detecting these spikes with high accuracy using the proposed 1D-ResCNN framework.

In EEG, artifact removal is indispensable as it eliminates unwanted signals originating from non-neural sources, allowing for precise interpretation of brain activity and enhancing the validity of research findings and clinical diagnoses. There are two primary artifacts found in EEG signals while predicting seizures: physiological artifacts and technical artifacts11. Physiological artifacts arise from internal bodily processes, including muscle activity and baseline noise. In contrast, technical artifacts are caused by external factors such as environmental disturbances stemming from power supply lines operating at frequencies of 50 or 60 Hz, light radiation, and radio frequency emissions caused by nearby medical devices12. Although techniques like ensuring proper electrode attachment can assist in reducing the effects of technical artifacts, it remains difficult to eliminate physiological artifacts.

Various effective methods, including Kalman filtering, Bayesian filtering, neural networks, and band-pass filtering, have been explored to reduce muscle and baseline noise13,14,15,16,17,18 in addition to popular noise elimination techniques like adaptive Filtering (AF) architecture, wavelet analysis, singular value decomposition(SVD), principal component analysis (PCA), and Independent Component Analysis (ICA)19,20,21,22,23. A few authors24,25 have explored the potential of the peak detection algorithm and have reported it to be effective in identifying spikes in EEG datasets. The authors have implemented such algorithms to detect spikes present in scalp EEG data.

Feature extraction is a critical step in identifying epileptic spikes from EEG recordings, with approaches generally classified into frequency-domain, time-domain, and time-frequency-domain techniques.These characteristics include kurtosis, variance, mean, median, skewness, and skewness, and they give important details on the structure and form of spikes26. Time-frequency domain features, using methods like Wavelet Transform and Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT), offer a balance between time and frequency representation, making them effective for detecting transients like epileptic spikes through wavelet coefficients and energy in specific bands27. Spectral power, power spectral density, and energy in frequency bands are examples of frequency-domain properties that are obtained by converting EEG data into the frequency domain utilizing techniques similar to as the fourier transform. These qualities help identify significant frequencies that are diagnostic of epileptic activity28.

Challenges in epileptic spike detection

The development of predictable systems requires addressing a number of clinical and technical issues related to epileptic spike identification in EEG signals.

-

1.

Spike morphology variability: Spikes exhibit varying shapes, durations, and amplitudes in patients, complicating detection. More flexible models are needed to capture these diverse patterns effectively.

-

2.

Artifact contamination: EEG signals are prone to physiological and technical artifacts that can mask or mimic epileptic spikes. The effective removal of artifacts without signal loss remains a key challenge, particularly for real-time applications.

-

3.

Class imbalance: Spike events are rare compared to non-spike segments, leading to biased models. Addressing this imbalance is crucial to maintaining high sensitivity and reduce false positives.

-

4.

Real-Time and resource constraints: Real-time detection requires lightweight models for deployment on limited hardware while maintaining accuracy. Balancing computational efficiency with detection performance is challenging.

-

5.

Generalization among patients: Spikes vary significantly during individuals, making it difficult for models to generalize across patient populations. Improving generalization without retraining is essential for greater clinical applicability.

State-of-the-art-techniques

The authors have explored numerous classifiers for assessing the performance metrics of models for epileptic seizure classification. The reference methods-Invented by Jaishankar et al.29 on Adaptive Grey Wolf Optimizer, Genetic Algorithm, and Auto encoders for effective seizure prediction with an accuracy of about 97.49%. In a way, so far the method subjects have to generalizability and clinical deployability.

Ra et al.30 proposed a method for predicting epileptic seizures by exploiting a synchronous-extracting transform (SET) in combination with a 1-dimensional convolutional neural network (1D-CNN). The method’s computational complexity may limit its practical applicability by relying on high-quality EEGs for continuous monitoring.

Chavan et al.31 developed an epileptic seizure detection model using the Human Learning Optimization (HLO) algorithm for electrode selection and a deep dual adaptive CNN-HMM classifier. However, the model’s high computational cost, extensive pre-processing requirements, and long training times could limit its applicability in real-time clinical settings.

Lu et al.32 introduced a seizure finding model mixing CBAM, 3D CNN, and Bi-LSTM, which reportedly outperforms recent methods by capturing both temporal and spatial EEG features. Despite its improved performance, the model’s computational complexity and resource demands hinder its practicality for real-time clinical use.

The study33 focuses on designing a hybrid deep learning model of MSA-DCNN and LSTM networks to enhance efficiency for predicting epileptic seizure detection. Compared to the original model based on signal reconstruction. This model may face the problem of generalizability across datasets due to less number of patient populations.

Jana et al.34 introduced a prediction of seizure model that less the number of EEG channels from 22 to just 3 while still achieving high levels of accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity. This is a minimum number of channels that allow achieving the wearable remotely powered device for real-time seizure prediction. The computational demand and the need for training data greatly reduce real-time adaptability. In addition, the variability and quality of EEG signals may limit the robustness of this model across other patient populations. Moreover, its patient-specific approach requires personalized training which may limit more widespread implementation and the demand of extensive pre-processing can result in additional time between pre-processing and predictions.

Lebal et al.35 developed the Epilepsy-Net model, a cutting-edge convolutional neural network-based deep learning framework. The model incorporates ResNet and a gated recurrent unit (GRU) with an attention mechanism to capture long-range dependencies, achieving up to 99.05% accuracy in epileptic seizure detection. However, the model faces challenges related to class imbalances in the datasets and the complexity of the model.

The article by Jebin et al.36 developed a seizure detection model that combines the Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM) for detailed texture analysis with AlexNet for high-performance classification. However, the performance of the model was impacted by the use of extensive pre-processing methods. Its computational complexity and sensitivity to EEG signal variability pose challenges for real-time applications and limit its deployment in resource-constrained settings.

The authors Pattnaik et al.37 explored a novel method for classifying epileptic seizures. This method employs transfer learning with the pre-trained ResNet50 model to classify 2D scalogram images generated from EEG signals via continuous wavelet transform (CWT). The model’s performance dependency on pre-trained networks may limit its adaptability to the new datasets.

To detect spikes associated with epilepsy in EEG recordings, we present a novel deep learning-based 1D Residual Convolutional Neural Networks (1D-ResCNN) model in this work. The framework integrates the Layer-wise Adaptive Moments (LAMB) algorithm and the AdamW optimizer, where weight decay is decoupled from the gradient update process in conventional Adam. With this integration, the model can discriminate more clearly between spike and non-spike signal. Figure 1 shows a flow chart describing the method and the sequence of steps performed to collect the raw data and to classify the EEG events.

In this article, the following are the contributions.

-

1.

Using 1D Residual Convolutional Neural Networks (1D-ResCNN), the model is able to detect epileptic spikes in EEG data with high accuracy, which is a significant improvement in automated EEG epilepsy analysis.

-

2.

The AdamW optimizer is integrated, which separates weight decay from the gradient update, enhancing time and frequency domain feature extraction from EEG signals. This strategy boosts training efficiency and results in faster convergence in contrast to conventional optimization techniques.

-

3.

The model is evaluated on diverse datasets, including the CHB-MIT scalp EEG dataset, where it demonstrates high sensitivity, accuracy, F1 score and specificity in detecting epileptic spikes.

-

4.

The architecture and optimization techniques provide an accurate and efficient tool for identifying spikes, facilitating early diagnosis and personalized treatment, thus potentially improvement of the standard of living for those with epilepsy.

-

5.

This study introduces one of the first instances of implementing a hybrid 1D-ResCNN framework for epileptic spike detection using the Typhoon HIL real-time simulator. It integrates real-time data acquisition, processing, and seizure control through embedded C2000 microcontrollers, enabling accurate and immediate detection. This advanced validation setup holds promise for enhancing real-time clinical applications in epilepsy monitoring and management.

The article investigates an optimized 1D-ResCNN model for recognizing epileptic spikes using EEG data. The Introduction emphasizes the significance of spike detection in epilepsy and highlights the associated challenges. The State-of-the-Art Techniques section reviews existing seizure detection methods, particularly those leveraging machine learning and deep learning approaches. The provided Model section outlines the 1D-ResCNN architecture, the use of AdamW and LAMB optimizers, and provides details of the training and testing processes. In the Simulation Results & Discussions section, the pre-processing and feature extraction methods are detailed, results from the CHB-MIT and Siena datasets are presented, and the model’s performance is compared to existing methods. The Hardware Implementation for Real-Time Epileptic Spike Detection Using Typhoon HIL section describes the hardware validation of the model using the Typhoon HIL real-time simulator, along with a comparison of the performance of the suggested model against others. The final section, Ablation Study & Conclusion, discusses an ablation study and provides concluding remarks.

Proposed model

A complete illustration of the suggested 1D-ResCNN architecture has been demonstrated in Fig. 2, which also shows the size of every layer’s feature map and encapsulates the detailed strategy of the model for EEG signal classification.

The motivation for choosing 1D-ResCNN for epilepsy spike detection includes the following points:

-

1.

Efficient Feature Extraction from Sequential Data: 1D-ResCNN excels at capturing local patterns in sequential data, making them ideal for analyzing time and frequency series signals and extracting relevant features for classification tasks.

-

2.

Reduced Computational Complexity: 1D-ResCNN offers lower computational complexity and memory requirements compared to higher-dimensional CNNs, enabling efficient processing of input signals with limited resources.

-

3.

Suitability for High-Dimensional and High-Frequency Data: 1D-ResCNN effectively handle high-dimensional, high-frequency data by learning hierarchical representations, capturing both low-level and high-level patterns in the input signal.

-

4.

Integration with Residual Connections and Regularization Techniques: The combination of 1D-ResCNN with residual connections and dropout regularization enhances model robustness, mitigating vanishing gradients and preventing overfitting for accurate signal classification.

Convolutional layers

In many CNN architectures, the convolutional layer with 64 filters, a kernel size of 3, and “same” padding is a crucial part. This layer applies 64 distinct convolutional filters, each of size 3, to the input data. The ’same’ padding ensures that the output feature map retains the same spatial dimensions as the input by adding zero padding around the edges. This design enables the network to capture local patterns and features while preserving spatial resolution, which is essential for tasks like image segmentation and time and frequency series analysis. By using multiple filters, the network learns a broad range of features, improving its ability to generalize and excel across various tasks.

The convolutional layer applies \(C_{out}\) filters, each of size K, to an input tensor X of form \((N, L, C_{in})\), where N is the batch size, L is the length of the input sequence, and \(C_{in}\) is the number of input channels. This results in an output tensor Y of shape \((N, L, C_{out})\).

The output at position l and channel c is

where:

-

W is the weight tensor of shape \((K, C_{in}, C_{out})\),

-

b is the bias vector of shape \((C_{out})\),

-

\(\left\lfloor \cdot \right\rfloor\) denotes the floor function, ensuring that the kernel is centered around the current position l.

The ‘same’ padding ensures that the input and output lengths L are the same by adding \(\left\lfloor \frac{K}{2} \right\rfloor\) zeros to both ends of the input sequence.

Enhancing performance with the Swish activation function

In the proposed 1D Residual Convolutional Neural Network (1D-RCNN) architecture, the Swish activation function enhances model performance. Introduced by Google researchers, Swish is described as

where \(\sigma (x)\) is the sigmoid function

and \(\beta\) is a parameter, often set to 1, simplifying Swish to

One of its key advantages is its smoothness, as it is differentiable across the entire input domain. This property aids in gradient-based optimization, promoting smoother convergence and decreasing the possibility of becoming limited in local minima, unlike ReLU, which has a discontinuity at zero. Additionally, Swish’s non-monotonicity allows it to both increase and decrease in value, making it better suited to capturing detailed patterns in high-dimensional data such as EEG signals. This adaptability aids in the model’s discovery of more complex links in the data. Moreover, Swish is bounded below and unbounded above, allowing it to retain the beneficial properties of ReLU by growing towards infinity for positive inputs while approaching zero for large negative inputs. This feature, combined with its improved gradient flow, makes Swish particularly advantageous for deep networks, where maintaining gradient flow across layers is essential to avoid the vanishing gradient problem. Because both the input and the sigmoid function must be calculated, the computational cost is marginally higher than for simpler functions like ReLU. However, this additional complexity is often justified by the performance gains it provides. For large negative inputs, Swish approaches zero, which can slow learning in certain cases, though this effect is typically less severe than in Sigmoid or Tanh. Additionally, while its non-monotonicity may sometimes lead to slower convergence, this is generally outweighed by the benefits of capturing more complex patterns in the data. These factors do not significantly detract from Swish’s effectiveness and overall contribution to model performance.

Stabilizing training with batch normalization in 1D-ResCNN

In the proposed 1D-ResCNN architecture, batch normalization is used to stabilize and accelerate the training procedure by normalizing each layer’s inputs, mitigating the internal covariate shift. Ioffe et al.38 introduced batch normalization maintains consistent input distributions, stabilizing gradients, and improves convergence speed. For a mini-batch of size \(m\), the mean \(\mu _B\) and variance \(\sigma _B^2\) of the inputs \(x\) are computed

Then inputs are normalized

For numerical stability, \(\epsilon\) is a tiny constant. The learnable parameters \(\gamma\) and \(\beta\) are used to scale and shift the normalized inputs.

Batch normalization offers several benefits: it stabilizes the training process, allows for reduces overfitting,higher learning rates, and mitigates internal covariate shifts. In the 1D-ResCNN architecture, batch normalization is applied after the Swish activation function in each convolutional block, ensuring consistent input distributions throughout the network.

Enhancing learning with residual connections in 1D-ResCNN

Residual connections in the proposed 1D-ResCNN architecture increase learning capabilities and address the vanishing gradient problem. Kaiming He et al.39, these connections simplify optimization by enabling the network to learn residual functions relative to layer inputs.

Mathematically, given an input \(x\) to a residual block with desired mapping \(H(x)\), the residual mapping \(F(x)\) is:

The output of the residual block

Deeper network training is made possible by residual connections, which give gradients a direct path and reduce the vanishing gradient issue. They also facilitate iterative feature refinement, enhancing feature representation and performance on complex tasks. In the 1D-ResCNN architecture, residual connections are added after each convolutional block, creating a shortcut path that bypasses intermediate layers, as illustrated in Fig. 2. Incorporating residual connections improves training stability, convergence speed, and feature learning, making the model robust for various deep-learning tasks. This ensures effective learning and generalization, leading to better performance and accuracy.

Regularizing with dropout in 1D-ResCNN

In the proposed 1D-ResCNN architecture, dropout is employed to prevent overfitting and improve generalization. Introduced by Geoffrey Hinton et al.40, randomly dropout“drops out” a percentage of neurons during training. The dropout rate, typically between 0 and 1, determines the fraction of neurons to drop. For example, a dropout rate of 0.5 drops 50% of the neurons during each training iteration. Mathematically, a binary mask \(m\) is generated for each layer, where each element is drawn from a Bernoulli distribution with probability \(p\) (the dropout rate).

The layer output \(y\) is modified by element-wise multiplication with the dropout mask \(m\)

where \(\odot\) denotes element-wise multiplication. During training, outputs are scaled by \(\frac{1}{p}\)

Dropout benefits the model by preventing reliance on specific neurons, reducing co-adaptation, and promoting robust feature learning. It effectively trains an ensemble of subnetworks, improving generalization to new data. In the 1D-ResCNN architecture, dropout is applied after residual blocks and before fully connected layers, with a dropout rate of 50%.

Flatten layer in 1D-ResCNN

The flatten layer in the 1D-ResCNN architecture bridges the fully connected layers and convolutional layers. It transforms the multi-dimensional output of convolutional layers into a one-dimensional vector for subsequent dense layer processing.

The output of the convolutional layers, including residual connections and batch normalization, is typically a multi-dimensional tensor. For example, if the output tensor has dimensions \((N, L, C)\), where \(N\) is the batch size, \(L\) is the sequence length, and \(C\) is the number of channels (filters), the flatten layer reshapes this tensor into a 1D vector of size \(N \times (L \times C)\).

In the 1D-ResCNN architecture, the flatten layer is applied after the dropout layer following the final residual connection. For instance, if the output tensor from the dropout layer has dimensions \((20, 64)\), it is flattened into a one-dimensional vector of size \(768\). This vector is then fed into the dense layers for further processing and classification.

The flatten layer ensures that each element of the tensor is preserved and can be used as input to the dense layers, facilitating the final classification or prediction tasks.

Dense layers in 1D-ResCNN

Dense layers are essential to the proposed 1D-ResCNN architecture because they convert the high-level features that the convolutional layers extract into predictions for the final output. Dense layers, also known as fully connected layers, enable thorough feature integration and prediction by connecting every neuron to every other neuron in the layer above.

An activation function is carried out after a linear transformation by a dense layer:

where the weight matrix is represented by \(\textbf{W}\), the input vector by \(\text {input}\), the bias vector by \(\textbf{b}\), and the activation function by \(\text {activation}\).

In the 1D-ResCNN architecture, dense layers are applied after the flatten layer, which converts the multi-dimensional output of the convolutional layers into a one-dimensional vector. The architecture includes two dense layers: the first with 256 units and Swish activation, and the second with 512 units and Swish activation. These layers process the flattened vector, capturing intricate data patterns. The final dense layer, the output layer, has 2 units with a softmax activation function, producing classification probabilities for “spike” and “non-spike.”

Optimization techniques used in 1D-ResCNN

In the 1D-ResCNN architecture, the optimization process for spike detection leverages both the AdamW and LAMB optimizers, each contributing unique advantages that boost the model’s overall performance and stability. AdamW decouples weight decay from gradient updates, improving convergence and generalization, while LAMB optimizes large-batch training, ensuring better scalability and efficiency. AdamW optimizer: The AdamW optimizer was selected for its ability to decouple weight decay from the gradient update step, unlike the traditional Adam optimizer, which combines weight decay with learning rate updates. By applying weight decay separately, AdamW ensures better regularization and reduces overfitting. This approach prevents the model from converging to suboptimal solutions by penalizing large weight values. In our study, the weight decay parameter was set to \(1 \times 10^{-5}\), which allows the model to generalize effectively without overfitting to the training data. By balancing regularization and learning dynamics, AdamW ensures stable convergence while maintaining high accuracy, even when applied to high-dimensional EEG data.

LAMB Optimizer: The optimizer LAMB have been employed to tackle the difficulties of large-batch training, which is frequently necessary for high-dimensional EEG data. LAMB adjusts the learning rate for each layer independently, allow the model to take advantage of adaptive learning rates throughout its layers. This technique stabilizes the training process and accelerates convergence, making it especially advantageous for intricate models like 1D-ResCNN, where accurate optimization is essential for precise spike detection.

Together, these optimizers form a robust framework for training deep learning models by effectively mitigating overfitting and addressing gradient instability issues. The categorical cross-entropy loss function was applied to handle the binary classification task (spike vs. non-spike), with model performance evaluated based on accuracy metrics throughout the training process.

The integration of AdamW and LAMB optimizers at the dense layer stage is visually summarized in Fig. 3, which illustrates their roles in optimizing weight updates and contributing to the robustness of the final classification results. This comprehensive approach ensures that the 1D-ResCNN model is both efficient and reliable for spike detection tasks, as demonstrated by the interaction of the optimizers with the layers to produce accurate spike and non-spike classifications.

Training and testing methods used for 1D-ResCNN

The suggested spike detection model has been trained over 150 epochs. This allows the network to learn and fine-tune weights through multiple iterations over the training datasets, balancing training time and model convergence. A batch size of 5 is used, enabling faster convergence and better generalization by providing more frequent updates to the model parameters.

The proposed 1D-ResCNN model classifies input signals into “spike” and “non-spike” categories, with hyperparameters detailed in Table 1. The architecture starts with an input signal of size \(20 \times 1\), processed through four convolutional blocks. Each block contains a 1D convolutional layer, Swish activation, and batch normalization, with residual connections between blocks. A dropout layer with a 50% dropout rate is applied after the convolutional blocks to prevent overfitting. The output is flattened and passed through two dense layers with 256 and 512 units using Swish activation. Softmax activation has been employed in the final output layer to generate classification probabilities.

Simulation result and discussions

To implement the recommended methods, a CPU Core i7 with 16 GB of RAM and 1.5 MB of L2 cache had been utilized. The implementation was carried out using Python and MATLAB, along with Windows 11 as the operating system. We assessed the performance of the technique using metrics such as sensitivity, accuracy, specificity, FPR, and F1-score for spike detection34. Additionally, this section covers the preprocessing steps for the EEG dataset, the peak detection method, the feature extraction techniques for spike and non-spike data, and the simulation and hardwere results of the 1D-ResCNN architecture. The study finish with a discussion of the findings and potential future research directions.

Dataset and pre-processing

CHB-MIT dataset

The CHB-MIT EEG dataset from PhysioNet.org, developed by MIT and Boston Children’s Hospital, is used to identify spikes and seizures. 22 young children’s 844 hours of scalp EEG data were recorded using a bipolar montage with 22 electrodes positioned in accordance with the worldwide 10-20 standard, at a sampling rate of 256 Hz. All channels are used in this investigation to detect spike and non-spike events. 24 sets of long-term EEG recordings from 12 patients-9 girls, ages 1.5–14.5 and 3 boys, ages 3.5–11-who were all referred for pre-surgical epilepsy assessment make up the dataset.

Siena dataset

This work used the Siena dataset, which is accessible at [PhysioNet](https://physionet.org/content/siena-scalp-eeg/1.0.0/)41. Provided by the Unit of Neurology and Neurophysiology at the University of Siena, Italy, the dataset is focused on seizure prediction.It contains 14 adult patients’ scalp EEG recordings that were taken a few days after they stopped taking antiepileptic medication. 512 Hz sample rate and 29 channels were used to record the majority of these continuous EEG recordings. For this study, data from 10 patients have been used.

Pre-processing

The EEG signals in this study were recorded with 16-bit resolution, ensuring that each data point captured subtle variations in amplitude, which is particularly important for detecting small and transient events such as epileptic spikes. In the pre-processing stage, two key filtering techniques were applied to improve signal quality. A band-pass filter with a frequency range of 0.1-80 Hz was used to retain relevant information within this frequency band while attenuating both high-frequency noise and low-frequency drifts. This step ensured that important features of the EEG, including epileptic spikes, were preserved while eliminating unwanted artifacts. Additionally, a notch filter was applied to remove the 50 Hz frequency associated with power line interference, which is commonly encountered in clinical environments and could otherwise obscure critical signal components. Figure 4a illustrates the raw EEG signal recorded with the 16-bit resolution before any processing. Following the application of these pre-processing techniques, the resulting cleaned signal is shown in Fig. 4b, where artifacts and noise have been significantly reduced.

Peak detection

The algorithm takes a pre-processed EEG dataset as input, where \(X = \{x_1, x_2, \ldots , x_n\}\) represents the data points25. Which consists of data from 12 patients, it defines several thresholds and parameters, including a minimum peak prominence threshold \(T_p = 1 \, \upmu \text {V}\), maximum peak duration \(T_{\text {max}} = 20 \, \text {ms}\), minimum spike duration \(T_{\text {min}} = 70 \, \text {ms}\), minimum spike amplitude \(A_{\text {min}} = 700 \, \upmu \text {V}\), and maximum wave duration \(T_{\text {maxdur}} = 30 \, \text {ms}\). The algorithm identifies 189,529 spikes and 189,517 non-spike waveforms in the dataset.

After identifying all spikes, the algorithm processes each spike \(p_j\) in the list P. For each spike, it defines a non-spike window W relative to the spike, where ‘start’ is \(p_j - T_1\) (with \(T_1\) being the duration before the spike) and ‘end’ is \(p_j + T_2\) (with \(T_2\) being the duration after the spike). It then extracts the non-spike waveform within the window W from the original signal X and adds it to the list S. Finally, the algorithm outputs the identified spikes and non-spike waveforms as a tuple (P, S), where \(P = \{p_1, p_2, \ldots , p_m\}\) denotes the indices or time points of the identified spikes. This method ensures that only significant peaks are classified as spikes, while non-spike waveforms are also extracted for further analysis.

The dataset used in this study is imbalanced, with a significantly higher number of non-spike events compared to spike events. This imbalance can negatively impact the model’s performance, as it may lead to a bias toward predicting the majority class (non-spike events), resulting in a higher rate of false negatives for the minority class (spike events). To address this issue, several data balancing techniques were implemented. Oversampling of the minority class (spike events) was performed to artificially increase the number of spike events in the training dataset. If the number of spike events is denoted by \(N_{\text {spike}}\) and the number of non-spike events by \(N_{\text {nonspike}}\), oversampling was used to match the number of spike events to that of non-spike events, such that the effective size of the spike class becomes

where \(N_{\text {aug}}\) represents the additional synthetic spike samples. This process ensured that spike events were adequately represented, enabling the model to better learn their distinguishing characteristics. Undersampling of the majority class (non-spike events) was also performed to further balance the dataset by reducing the number of non-spike samples. This can be expressed as reducing the size of the non-spike class to match the spike class, so that the final balanced dataset satisfies \(N_{\text {nonspike}} = N_{\text {spike}}.\) This helped prevent the model from being overly biased toward the non-spike class by limiting its exposure to an overwhelming number of non-spike samples. Additionally, data augmentation have been applied to increase the diversity of spike events. Given a spike event \(s_i\), slight perturbations were introduced by adding Gaussian noise \(\epsilon \sim N(0, \sigma ^2)\), shifting the signal in time \(s_i'(t) = s_i(t + \Delta t)\), and applying small scaling factors to the amplitude \(s_i''(t) = \alpha \cdot s_i(t)\), where \(\Delta t\) and \(\alpha\) are small random values. These transformations preserved the core characteristics of the original spike signals while enhancing the variety of spike events in the training set. This augmentation technique allowed for an effective increase in the size of the minority class without introducing redundancy.

Feature extraction

A comprehensive feature extraction process has been used to improve the analysis of EEG signals for the detection of epileptic spikes by integrating features in the time and frequency domains. The features of time-domain have been extracted, including Mean Absolute Value, Root Mean Square (RMS), Variance, Standard Deviation, Kurtosis, Skewness, Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), Mean Absolute Deviation (Mean AD), Median Absolute Deviation (MED AD),Simple Square Integral (SSI)42,43,44. Furthermore, power spectral density (PSD) and Band Power metrics have been included as frequency-domain features, covering key frequency bands such as Delta (0.5–4 Hz), Theta (4–8 Hz), Alpha (8–13 Hz), Beta (13–30 Hz), and Gamma (30–70 Hz), along with their respective relative band powers45,46. These features provide insights into the spectral characteristics of EEG signals and their oscillatory nature. By combining temporal and spectral information, this feature extraction approach has ensured a holistic representation of EEG data, significantly improving the ability of 1D-ResCNN model’s to accurately distinguish epileptic spikes from non-spike patterns.

Performance evaluation

For analyzing the performance of the 1D-ResCNN model in recognizing spikes and non-spikes, the following metrics and their corresponding formulas are used:

Accuracy: This metric evaluates the accuracy of the model’s prediction. It is computed as the proportion of true positive (TP) and true negative (TN) predictions relative to the total number of predictions made.

Sensitivity (Recall): Sensitivity assesses the model’s ability to correctly identify spike events. It is computed as the ratio of true positive (TP) predictions to the total number of actual spike events, which includes both true positives and false negatives (FN).

Specificity: Specificity measures the model’s ability to accurately detect non-spike events (negative examples). It is calculated as the ratio of true negative (TN) predictions to the total number of actual non-spike events, which includes both true negatives and false positives (FP).

False Positive Rate (FPR): FPR represents the ratio of negative instances that are incorrectly classified as positive. It is calculated as the ratio of false positives (FP) to the total number of actual negative instances, which includes both false positives and true negatives (TN).

F1-score: The F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall (sensitivity), giving a balanced measure that is particularly useful when interacting with imbalanced class distributions. Precision is the ratio of true positive (TP) predictions to the total number of positive predictions (true positives and false positives).

These measures offer a thorough assessment of the 1D-ResCNN model’s performance to detecting spikes and correctly identifying non-spikes in EEG data.

The performance metrics of the suggested 1D-ResCNN model, evaluated on the CHB-MIT dataset after 150 epochs, are presented in Table 2. These results for 12 different patients (chb01 to chb13) are crucial for assessing the model’s ability to detect epileptic spikes and non-spike events. Performance demonstrates results, with an accuracy ranging from 99.3% to 100.00% and an averaging of 99.71%. Sensitivity ranges from 99.2% to 100.00% with an average of 99.60%, while the specificity ranges from 99.25% to 100.00% with an average of 99.61%. The FPR remains notably low, between 0.0000 and 0.0080, averaging 0.0040. The F1-score ranges from 99.28% to 100.00%, averaging 99.71%. These values collectively reflect the robustness and reliability of the model in classifying EEG events with high precision and minimal false positives.

The performance metrics of the proposed 1D-ResCNN model have been evaluated on the Siena dataset, as presented in Table 3. These metrics include accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, FPR (FPR), and F1-score for 10 patients (P00 to P17). The results indicate outstanding performance, with an accuracy ranging from 99.0% to 100.00% and an average of 99.75%. The sensitivity varies between 98.5% and 100.00%, with an average of 99.94%, highlighting the model’s effectiveness in correctly identifying epileptic spikes. The specificity ranges from 99.0% to 100.00%, averaging 99.95%, demonstrating the model’s ability to accurately classify non-spike events. The FPR remains exceptionally low, ranging from 0.0000 to 0.0025, with an average of 0.0011, reflecting minimal false positives. The F1-score, which measures the balance between precision and recall, ranges from 99.25% to 100.00% and averages 99.74%. These results underscore the robustness of the 1D-ResCNN model, achieving high performance across all metrics and affirming its reliability for epilepsy detection on both the CHB-MIT and Siena datasets.

Minimizing false positives in clinical settings

In emergency medical contexts, false positives in epileptic spike detection can lead to unnecessary interventions, such as administering anti-epileptic drugs, resulting in side effects, patient distress, and misallocation of resources. False positives can also contribute to alarm fatigue, where frequent alerts desensitize staff to actual emergencies, potentially delaying necessary treatment. To mitigate these risks, the 1D-ResCNN model is designed to balance sensitivity and specificity. High specificity is crucial to reduce false positives while maintaining accurate spike detection. In our evaluations with the CHB-MIT and Siena datasets, the model achieved a specificity of CHB-MIT on 99.61% and 99.85%, minimizing false alarms. Real-time implementation on embedded hardware enables continuous monitoring and reduces the likelihood of acting on false positives. The model’s generalizability across datasets ensures reliable performance in different clinical settings, further reducing false positives. Incorporating post-processing steps, such as reviewing spikes in context with surrounding EEG patterns, can assist clinicians in confirming diagnoses before taking action. This careful design and optimization make the model a reliable tool that minimizes false positives and enhances the quality of care in emergency epilepsy management.

Evaluation of 1D-ResCNN in comparison to other existing approaches

Table 4 presents the evaluation metrics of the proposed 1D-ResCNN model in comparison with existing models on the CHB-MIT and Siena datasets. Key performance indicators such as accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, FPR (FPR), and F1-score are included to provide a comprehensive assessment of each model’s.

Jaishanker et al.29 achieved an accuracy of 97.49% and sensitivity of 95.9% on the CHB-MIT dataset, but their specificity was limited to 95.9%, indicating moderate performance compared to other models. Chavan et al.31 reported an accuracy and specificity of 99.46% on the CHB-MIT dataset and achieved a strong F1-score of 99.58%. However, their performance on the Siena dataset showed lower accuracy 94.53% and sensitivity 92.37%, reflecting variability across datasets. Lu et al.32 delivered an accuracy of 97.95% and sensitivity of 98.4% on the CHB-MIT dataset, with an FPR of 0.017, although specificity and F1-score were not reported. Anita et al.33 achieved balanced metrics of 96.7% across accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity on the CHB-MIT dataset, but their relatively high FPR of 0.03299 limited their reliability for real-time applications. Similarly, Jana et al.34 reported accuracy of 96.51% on the CHB-MIT dataset, with sensitivity and specificity near 96.5%, but did not provide other metrics. Lebal et al.35 demonstrated high sensitivity 99.58% and accuracy 99.05% on the CHB-MIT dataset, although specificity and FPR values were missing. Pattnaik et al.37 achieved an accuracy of 95.23% on the CHB-MIT dataset with high sensitivity 99.54% but low specificity 90.28%, resulting in a higher rate of false positives. Kumar et al.47 reported excellent accuracy 99.69% and sensitivity 99.68% on the CHB-MIT dataset but had slightly lower specificity 97.3% and an FPR of 0.0269. On the Siena dataset, this model performed well, achieving accuracy and sensitivity exceeding 99%. Similarly, Upadhyay et al.48 achieved accuracy of 99.66% and sensitivity of 98.49% on the CHB-MIT dataset, though their FPR of 0.0210 was higher than that of the proposed model. The proposed 1D-ResCNN model demonstrates superior performance. In the CHB-MIT dataset, it achieved the highest accuracy 99.71%, sensitivity 99.6%, specificity 99.61%, and F1-score 99.71%, with the lowest FPR 0.004. On the Siena dataset, the model performed exceptionally well, achieving accuracy 99.75%, sensitivity 99.94%, specificity 99.95%, an FPR of 0.0011, and an F1-score of 99.74%. These results underscore the robustness and reliability of the proposed model, which consistently outperforms existing methods on both datasets. Its higher accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and F1-scores, coupled with a lower FPR, confirm its capability for robust real-time epileptic spike detection.

Hardware implementation for real-time epileptic spike detection using Typhoon HIL

The implementation of the hybrid optimization-enhanced 1D-ResCNN framework for epileptic spike detection in scalp EEG signals involves a real-time experimental setup using the Typhoon HIL environment as shown in Fig. 5. This setup is critical for achieving accurate and timely detection of epileptic seizures, which can enable prompt intervention and improved patient outcomes. Below, we describe the key components and processes involved in this hardware implementation.

Real-time data acquisition

The EEG datasets were integrated into the Typhoon HIL real-time simulator via a Python interface, allowing for seamless interaction between the simulation environment and the recorded EEG signals. Additionally, EEG recorder electrode modules can be directly connected to the analog pins of the Typhoon HIL system, enabling real-time acquisition of data from patients or animal models. This setup facilitates the continuous monitoring of brain activity and ensures that the data is captured with minimal latency, which is crucial for accurate seizure detection. To prepare the data for analysis, the recorded EEG signals were divided into two halves: one for training the detection model and the other for evaluation. This approach ensures that the model is trained on representative samples and can generalize well to new data. The first 5 seconds after seizure onset were used as positive samples, as these segments typically contain the most informative features for early seizure detection. Negative samples were randomly selected to maintain a ratio of approximately 3:1 between negative and positive samples, helping to balance the model training process.

Signal processing and feature extraction

The EEG signals from six channels were recorded using the RHD2132 interface chip, which includes built-in analog filtering to prepare the signals for further processing. Cutoff frequencies for a first-order high-pass filter and a third-order Butterworth low-pass filter were set at 80 Hz and 0.1 Hz, respectively. This filtering stage is essential for removing unwanted noise and preserving the relevant frequency components of the EEG signals. The filtered signals were then sampled at 1 kHz, converted to 16-bit digital data, and sent to the Microcontroller within the Typhoon HIL system. To further clean the signals, a 50 Hz band-stop filter (second-order IIR) was applied to remove power line interference, which is common in EEG recordings.

Real-time seizure detection using Typhoon HIL

The Typhoon HIL environment, equipped with embedded C2000 microcontrollers, was configured to perform online seizure detection. The trained two-stage classifiers, one for each EEG channel, were implemented within this environment to ensure real-time processing and decision-making. In the first stage of the detection process, a mean filter with an 8-point length was applied to suppress false alarms. The selection of this filter length was based on the need to balance performance with detection latency, as longer filters could delay the detection process without significantly improving accuracy. After setting the segmentation window to 512 points, or roughly 0.5 seconds, it was slid with 512 points that did not overlap. This window length was chosen to optimize the trade-off between computational complexity and feature extraction effectiveness. Shorter windows might reduce feature effectiveness, while longer windows would increase the computational burden, particularly for complex features.

Real-time monitoring and control

The Typhoon HIL system also facilitates real-time monitoring and control of epileptic seizures. Once a seizure is detected, the system can trigger alarms or other intervention mechanisms to alert medical personnel. The seizure detection rate, false alarm rate, and detection delay have been employed to assess the system’s performance. Alarms triggered within 5 seconds of the onset of seizure were considered true positives, and the detection delay was calculated as the time difference between the true positives and the actual seizure onset marks. The ability to perform real-time analysis and control within the Typhoon HIL environment is particularly advantageous for clinical applications, where immediate response to seizure events is critical. The described hardware setup is scalable and can be adapted for more channels or different patient populations.

The hardware performance metrics of the 1D-ResCNN model, as detailed in Table 5, provided essential insights into the efficiency and real-time capabilities of the model when implemented on the C2000 microcontroller. With an inference time of 30 milliseconds per sample, the model ensures near real-time processing, which is crucial for the timely detection of seizures in clinical environments. Furthermore, the 50-millisecond latency ensures that the system outputs detection results promptly, which is particularly important in emergency settings where immediate intervention is critical. The model’s computational efficiency, operating at 1.5 GFLOPS, reflects its ability to handle 1.5 billion floating-point operations per second. This level of computational performance allows the C2000 microcontroller to process complex EEG data without the need for excessive resources. The power consumption of 5 watts further enhances its applicability for portable, low-power devices, which is essential for continuous patient monitoring in resource-constrained settings. Memory usage of 150 MB ensures that the model runs efficiently within the C2000’s memory limitations, while the compact model size of 2 MB makes it suitable for deployment on systems with limited storage capacity.

Computational complexity and processing time

In emergency situations, quickly identifying epileptic spikes is critical for prompt intervention. The 1D-ResCNN model has been assessed for its computational efficiency and processing speed to confirm its suitability for real-time use. Its streamlined design prioritizes minimizing parameters and reducing the computational burden, making it an excellent choice for implementation on embedded systems like the Typhoon HIL hardware, which uses the C2000 microcontroller. During testing, the model analyzed EEG segments with an average latency of just 50 milliseconds per segment, ensuring near-instantaneous results. The computational complexity, measured in floating point operations per second (FLOPS), showed the model achieving 1.5 GFLOPS (giga-FLOPS), comfortably meeting the requirements for real-time EEG monitoring in urgent scenarios. Validation on the Typhoon HIL system confirmed that the model processes EEG data streams with minimal lag, facilitating rapid alerts for detected spikes or abnormalities. This real-time capability is vital for clinical decision-making during emergencies, where rapid action can dramatically improve patient outcomes.

Real-time hardware-based validation results

Tables 6 and 7 summarize the real-time performance of the 1D-ResCNN model evaluated in both datasets using the C2000 microcontroller. The inclusion of both time-domain and frequency-domain features significantly enhances the model’s ability to effectively identify epileptic spikes and non-spike events in real-time. Table 6 presents an average accuracy of 99.65%, sensitivity of 99.54%, and specificity of 99.56%, demonstrating the model’s ability to accurately classify EEG events. The FPR (FPR) remains exceptionally low at 0.0042, effectively minimizing false alarms in a real-time setting. The F1-score averages 99.66%, indicating a well-balanced performance in detecting the prediction true spike.

The Siena data set has been evaluated using the C2000 microcontroller, demonstrating robust real-time performance in Table 7. The model achieves an average accuracy of 99.60%, a sensitivity of 99.40%, and a specificity of 99.80%. These results underscore the model’s effectiveness in distinguishing between epileptic spikes and non-spike events in real-time applications. The FPR remains low at 0.00145, ensuring minimal false alarms, which is crucial for clinical reliability. The F1-score averages 99.70%, reflecting a well-balanced trade-off between precision and recall. Performance remains consistently high in all patients, with particularly notable results for P07 and P17, where accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity approach their maximum values. These findings, combined with results from both datasets, confirm the robustness and reliability of the 1D-ResCNN model in real-time epileptic spike detection when implemented on hardware.

In addition to accuracy, the proposed 1D-ResCNN model offers several key advantages.

-

1.

Real-Time Implementation: Unlike many existing approaches, our model has been successfully implemented on the Typhoon HIL hardware platform, enabling real-time epileptic spike detection. This real-time capability is critical for clinical applications, where timely detection can lead to more effective interventions. Our model demonstrated an average detection latency of 50 ms, making it highly suitable for deployment in real-time monitoring systems.

-

2.

Computational Efficiency: The model is lightweight and computationally efficient, making it feasible for deployment on embedded systems with limited resources, such as the C2000 microcontroller. This efficiency ensures that the model can operate in resource-constrained environments without sacrificing performance, a crucial factor for portable EEG monitoring systems.

-

3.

Interpretability: The use of traditional feature extraction methods alongside deep learning contributes to the model’s interpretability. By incorporating well-established features from the field of EEG analysis, clinicians can better understand how the model makes decisions, making it more transparent and trustworthy for clinical use.

-

4.

Generalizability: The suggested model was evaluated using the CHB-MIT and Siena datasets, demonstrating its ability to apply between different patient populations and recording environments.This robustness is essential because models in real-world applications must perform consistently over various kinds of datasets.

-

5.

Hardware Integration: One of the key strengths of this work is the successful integration of the model with Typhoon HIL hardware, which allows real-time spike detection on embedded systems. This integration makes the model more practical for real-world use as it bridges the gap between theoretical models and hardware-based clinical solutions.

These advantages make the proposed approach not only highly accurate but also practical, efficient, and applicable for real-time epileptic spike detection in clinical settings.

Real-time hardware-based comparison with different algorithms

The hardware performance in real time of the proposed 1D-ResCNN model has been compared with SNSDeepNet47 and SeizureNet-BiLSTM48 on the same hardware platform, as presented in Table 8. The results demonstrate that the observed superior performance is attributed to the proposed algorithm. In the CHB-MIT dataset, 1D-ResCNN achieves the highest average accuracy 99.65%, specificity 99.56%, and F1-Score99.66%, with the lowest FPR 0.0042, surpassing the other models. Similarly, on the Siena dataset, the proposed model excels with an accuracy of 99.60%, sensitivity of 99.40%, specificity of 99.80%, FPR of 0.00145, and F1-Score of 99.70%. These findings validate that the outstanding real-time performance is primarily due to the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm, as it consistently outperforms alternative models on the same hardware platform.

Clinical applicability and impact

The reported 1D-ResCNN model is not only designed for high accuracy in spike detection but also for real-time implementation, making it highly applicable in emergency clinical settings. Early and accurate detection of epileptic spikes is crucial for preventing seizures, particularly in emergency situations where timely intervention can significantly affect patient outcomes. The model’s ability to operate on embedded hardware platforms, such as the Typhoon HIL and C2000 microcontroller, ensures that it can be deployed in portable monitoring devices for real-time diagnosis. The real-time performance of the model, with an average detection latency of 50 ms ensures rapid identification of spikes, enabling immediate intervention. This is particularly important in emergency settings, where delays in diagnosis could lead to severe consequences, including prolonged seizures, injury, or other complications. By detecting spikes promptly, clinicians can initiate treatment earlier, potentially preventing full seizures and reducing the risk of status epilepticus, a life-threatening condition in which seizures last longer than five minutes or occur in quick succession without recovery. In addition to its diagnostic potential, the efficiency of the model allows for continuous, real-time monitoring in hospital emergency rooms or during patient transport. Its portability makes it suitable for use in ambulatory EEG monitoring, giving patients the ability to be monitored outside of the hospital environment while still receiving real-time seizure alerts. This is especially valuable in critical care and intensive care units, where continuous monitoring is essential for patients with frequent seizures. By integrating the proposed model into existing clinical workflows, it is expected to speed up and accuracy of epileptic spike detection, leading to better patient outcomes. The combination of real-time implementation, low computational demands, and high accuracy provides a robust tool for emergency interventions in epilepsy management, enhancing patient safety and care.

Ablation study

Table 9 compares the performance of the Swish and ReLU activation functions on the CHB-MIT dataset. Swish achieves exceptional results, with an average accuracy of 99.71%, sensitivity of 99.6%, specificity of 99.61%, FPR of 0.004, and F1-score of 99.71%, demonstrating its effectiveness in classifying EEG signals. In contrast, ReLU shows reduced performance, with accuracy at 98.5%, sensitivity at 98.3%, specificity at 98.4%, FPR at 0.02, and F1-score at 98.4%. As shown in Table 10, Swish also outperforms ReLU on the Siena dataset across all metrics, achieving an accuracy of 99.75%, a sensitivity of 99.94%, a specificity of 99.95%, FPR of 0.00112, F1-score of 99.74%. ReLU delivers comparatively lower metrics, with accuracy at 98.8%, sensitivity at 98.60%, specificity at 98.70%, FPR at 0.02, and F1-score at 98.65%. The comparative results demonstrate that Swish outperforms ReLU in both datasets, validating its suitability for the proposed 1D-ResCNN model. Its smooth and non-monotonic properties enable better gradient flow and learning of complex EEG patterns, leading to higher accuracy, sensitivity, and reduced false positives. These improvements confirm the effectiveness of Swish’s and justify its inclusion in the framework for epileptic spike detection.

The suggested ablation study strategy for classification spike and non-spike events, as presented in Table 11, evaluates the model’s functionality on both the CHB-MIT and Siena datasets using varying numbers of CNN blocks (from 1 to 4). As the number of CNN blocks increases, the model’s performance steadily becomes better for the CHB-MIT dataset. The model achieves 98.71% accuracy, 97.31% sensitivity, 99.18% specificity, 0.0080 FPR, and 98.64% F1-score with a single CNN block. The FPR drops to 0.0071 when the number of blocks is raised to two CNN blocks, but the accuracy, sensitivity, and F1-score all improve to 99.04%, 99.34%, and 99.15%, respectively. The accuracy rises to 99.19% and the FPR falls to 0.0029 with three CNN blocks, indicating less incorrect classifications. Finally, using 4 CNN blocks, the model achieves its best performance, with an accuracy of 99.49%, sensitivity of 99.41%, specificity of 99.35%, an FPR of 0.0071, and an F1-score of 99.44%. For the Siena dataset, a similar trend is observed. With 1 CNN block, the model achieves an accuracy of 96.11%, sensitivity of 98.11%, and specificity of 85.60%, with an FPR of 0.1440. By expanding the number of blocks to 2 CNN blocks, the model significantly improves, reaching 98.31% accuracy and 100.00% sensitivity, with specificity rising to 96.11% and the FPR dropping to 0.0333. With 3 CNN blocks, the model shows further improvement with an accuracy of 99.34%, sensitivity of 98.95%, and specificity of 99.33%, althrough the FPR increases slightly to 0.0476. Finally, with 4 CNN blocks, the model achieves the best performance, with an accuracy of 99.60%, sensitivity of 99.26%, specificity of 99.80%, an FPR of 0.0029, and an F1-score of 99.44%. This ablation study shows that increasing the number of residual CNN blocks consistently improves the model’s performance for spike and non-spike classification. The model with 4 CNN blocks achieves the highest accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and F1-score on both datasets, while maintaining a low FPR, making it highly effective for real-time classification of epileptic spikes and non-spike events.

Table 12 presents the performance metrics of the 1D-ResCNN model using only frequency domain features for the detection of epileptic spikes in the CHB-MIT and Siena datasets. In the CHB-MIT dataset, the model achieves an accuracy of 99.55%, sensitivity of 99.46%, specificity of 99.48%, and an F1-score of 99.53%, with a low FPR of 0.0048. These metrics indicate the model’s strong ability to classify EEG events accurately, even when relying solely on frequency-domain features. For the Siena dataset, the model performs equally well, achieving an accuracy of 99.64%, sensitivity of 99.36%, specificity of 99.80%, and an F1-score of 99.51%, with an even lower FPR of 0.0022.

Table 13 presents the results when using only time-domain features for epileptic spike detection on the CHB-MIT and Siena datasets. For the CHB-MIT dataset, the model achieves an accuracy of 99.49%, sensitivity of 99.41%, specificity of 99.35%, and an F1-score of 99.44%, with a FPR of 0.0071. These results highlight the model’s ability to accurately classify EEG events based solely on time-domain features. On the Siena dataset, the model achieves slightly higher metrics, with an accuracy of 99.60%, sensitivity of 99.26%, specificity of 99.80%, and an F1-score of 99.44%, along with a low FPR of 0.0029.

The performance metrics of the 1D-ResCNN model when utilizing a combination of features in the time and frequency domains are shown in Table 14. The model’s results for the CHB-MIT dataset include an F1-score of 99.71%, a low FPR of 0.0040, accuracy of 99.71%, sensitivity of 99.60%, and specificity of 99.61%. These findings demonstrate that combining the two feature domains significantly improves classification performance. The model performs even better on the Siena dataset, with an F1-score of 99.74%, an extraordinarily low FPR of 0.0011, and accuracy of 99.75%, sensitivity of 99.63%, and specificity of 99.95%. This illustrates the model’s robustness and dependability in real-world datasets with a range of features.

Comparison of the three Tables 12, 13, 14 in the ablation study highlights that while the characteristic fetures of the time and frequency domain characteristic independently yield strong performance in epileptic spike detection, their integration delivers significantly superior results. The combined approach achieves higher accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity along with the lowest false positive rates, outperforming models using only time-domain or frequency-domain features. This synergy underscores the improved effectiveness and robustness of combining temporal and spectral information, making the 1D-ResCNN model more reliable and generalizable for EEG classification across the CHB-MIT and Siena datasets.

Conclusion

In order to detect epileptic spikes in real time, this research suggested a deep learning framework that makes use of 1D-ResCNN. The model was optimized using AdamW and Layer-wise Adaptive Moments (LAMB) algorithms, enhancing its convergence and performance. The framework was evaluated in two public epilepsy datasets CHB-MIT and Siena. The model obtained 99.71% accuracy, 99.60% sensitivity, and 99.61% specificity in the CHB-MIT dataset, surpassing several state-of-the-art methods. Similarly, in the Siena dataset, the model demonstrated strong performance with an accuracy of 99.75%, an average sensitivity of 99.94%, and an average specificity of 99.95%. Additionally, hardware validation of the 1D-ResCNN model using the Typhoon HIL real-time simulator and C2000 microcontrollers demonstrated the model’s ability to process EEG data with minimal latency, making it suitable for deployment in clinical environments where real-time seizure monitoring is critical. The lightweight architecture, low power consumption, and robust performance ensure that it can be implemented in resource-constrained systems, offering reliable epileptic spike detection in real-time medical applications. The findings suggest that the proposed 1D-ResCNN framework holds significant promise for improving epilepsy management by providing accurate and timely spike detection, which can improve intervention outcomes and overall patient care.

The future scope of this work includes expanding the 1D-ResCNN model to incorporate broader EEG markers, such as abnormal rhythms and patterns of onset seizures, to enhance its clinical relevance for real-time seizure prediction. In addition, ongoing research aims to develop predictive models that can forecast epileptic spikes before clinical symptoms manifest, enabling early intervention. Future studies will focus on integrating these features and testing the model in diverse datasets, further improving its adaptability for real-time clinical use in critical care applications.

Data availability

The EEG data used in this study were obtained from the CHB-MIT Scalp EEG Database, which is publicly available at https://physionet.org/content/chbmit/1.0.0/. This dataset is hosted by PhysioNet, an online platform offering free access to a wide range of physiological data.

References

Manolis, T. A., Manolis, A. A., Melita, H. & Manolis, A. S. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: The neuro-cardio-respiratory connection. Seizure 64, 65–73 (2019).

Organization, W. H. et al. Epilepsy: A public health imperative (World Health Organization, 2019).

Gotlib, J. World Health Organization-defined eosinophilic disorders: 2014 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am. J. Hematol. 89, 325–337 (2014).

Iasemidis, L. D. et al. Adaptive epileptic seizure prediction system. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 50, 616–627 (2003).

Ullah, I. et al. An automated system for epilepsy detection using EEG brain signals based on deep learning approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 107, 61–71 (2018).

Mormann, F., Andrzejak, R. G., Elger, C. E. & Lehnertz, K. Seizure prediction: The long and winding road. Brain 130, 314–333 (2007).

Karoly, P. J. et al. Interictal spikes and epileptic seizures: Their relationship and underlying rhythmicity. Brain 139, 1066–1078 (2016).

Subota, A. et al. Signs and symptoms of the postictal period in epilepsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Epilepsy Behav. 94, 243–251 (2019).

Staley, K. J. & Dudek, F. E. Interictal spikes and epileptogenesis. Epilepsy Curr. 6, 199–202 (2006).

Gotman, J. Automatic detection of seizures and spikes. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 16, 130–140 (1999).

Stone, D. B., Tamburro, G., Fiedler, P., Haueisen, J. & Comani, S. Automatic removal of physiological artifacts in EEG: The optimized fingerprint method for sports science applications. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 12, 96 (2018).

Choubey, H. & Pandey, A. A new feature extraction and classification mechanisms for EEG signal processing. Multidimens. Syst. Signal Process. 30, 1793–1809 (2019).

Ji, D. et al. Epileptic seizure prediction using spatiotemporal feature fusion on EEG. Int. J. Neural Syst. (2024).

Bronzino, J. D. Biomedical Engineering Handbook 2, vol. 2 (Springer Science & Business Media, 2000).

Patil, A., Langoju, R., Joel, S., Patil, B. D. & Genc, S. Biomedical signal analysis. (2015).

Sameni, R., Shamsollahi, M. B., Jutten, C. & Clifford, G. D. A nonlinear Bayesian filtering framework for ECG denoising. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 54, 2172–2185 (2007).

Mateo, J. & Rieta, J. Application of artificial neural networks for versatile preprocessing of electrocardiogram recordings. J. Med. Eng. Technol. 36, 90–101 (2012).

Shao, S.-Y., Shen, K.-Q., Ong, C. J. & Wilder-Smith, E. P. Automatic EEG artifact removal: a weighted support vector machine approach with error correction. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 56, 336–344 (2008).

Sansone, M., Mirarchi, L. & Bracale, M. Adaptive removal of gradients-induced artefacts on ECG in MRI: A performance analysis of RLS filtering. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 48, 475–482 (2010).

Xu, L., Zhang, D. & Wang, K. Wavelet-based cascaded adaptive filter for removing baseline drift in pulse waveforms. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 52, 1973–1975 (2005).

Paul, J. S., Reddy, M. R. & Kumar, V. J. A transform domain SVD filter for suppression of muscle noise artefacts in exercise ECG’s. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 47, 654–663 (2000).

Lagerlund, T. D., Sharbrough, F. W. & Busacker, N. E. Spatial filtering of multichannel electroencephalographic recordings through principal component analysis by singular value decomposition. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 14, 73–82 (1997).

Medina Villalon, S. et al. Combining independent component analysis and source localization for improving spatial sampling of stereoelectroencephalography in epilepsy. Sci. Rep. 14, 4071 (2024).

Barr, R. E., Ackmann, J. J. & Sonnenfeld, J. Peak-detection algorithm for EEG analysis. Int. J. Biomed. Comput. 9, 465–476 (1978).

Abd El-Samie, F. E., Alotaiby, T. N., Khalid, M. I., Alshebeili, S. A. & Aldosari, S. A. A review of EEG and MEG epileptic spike detection algorithms. IEEE Access 6, 60673–60688 (2018).

Dastgoshadeh, M. & Rabiei, Z. Detection of epileptic seizures through EEG signals using entropy features and ensemble learning. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 16, 1084061 (2023).

Ma, D., Zheng, J. & Peng, L. Performance evaluation of epileptic seizure prediction using time, frequency, and time-frequency domain measures. Processes 9, 682 (2021).

Barneih, F. et al. Artificial neural network model using short-term fourier transform for epilepsy seizure detection. In 2022 Advances in Science and Engineering Technology International Conferences (ASET), 1–5 (IEEE, 2022).

Jaishankar, B., Ashwini, A., Vidyabharathi, D. & Raja, L. A novel epilepsy seizure prediction model using deep learning and classification. Healthcare Anal. 4, 100222 (2023).

Ra, J. S. et al. A novel epileptic seizure prediction method based on synchroextracting transform and 1-dimensional convolutional neural network. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 240, 107678 (2023).

Chavan, P. A. & Desai, S. An efficient epileptic seizure detection by classifying focal and non-focal EEG signals using optimized deep dual adaptive CNN-HMM classifier. Multimed. Tools Appl. 1–42 (2024).

Lu, X. et al. An epileptic seizure prediction method based on CBAM-3D CNN-LSTM model. IEEE J. Trans. Eng. Health Med. (2023).

Anita, M. & Kowshalya, A. M. Automatic epileptic seizure detection using MSA-DCNN and LSTM techniques with EEG signals. Expert Syst. Appl. 238, 121727 (2024).

Jana, R. & Mukherjee, I. Efficient seizure prediction and EEG channel selection based on multi-objective optimization. IEEE Access (2023).

Lebal, A., Moussaoui, A. & Rezgui, A. Epilepsy-net: attention-based 1D-inception network model for epilepsy detection using one-channel and multi-channel EEG signals. Multimed. Tools Appl. 82, 17391–17413 (2023).

Jebin, B. M., Rejula, M. A. & Eberlein, G. Neonatal seizure detection using GLCM feature extraction & AlexNet classification. Multimed. Tools. Appl. 1–17 (2024).

Pattnaik, S., Rao, B. N., Rout, N. K. & Sabut, S. K. Transfer learning based epileptic seizure classification using scalogram images of EEG signals. Multimed. Tools. Appl. 1–15 (2024).

Ioffe, S. & Szegedy, C. Batch normalization: Accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift. In International Conference on Machine Learning 448–456 (PMLR, 2015).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 770–778 (2016).

Srivastava, N., Hinton, G., Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: A simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. J Mach. Learn. Res. 15, 1929–1958 (2014).

Goldberger, A. L. et al. Physiobank, Physiotoolkit, and Physionet: Components of a new research resource for complex physiologic signals. Circulation 101, e215–e220. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.101.23.e215 (2000).

Ahmad, I. et al. [retracted] eeg-based epileptic seizure detection via machine/deep learning approaches: A systematic review. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 6486570 (2022).

Davis, J. J., Schübeler, F., Ji, S. & Kozma, R. Discrimination between brain cognitive states using shannon entropy and skewness information measure. In 2020 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), 4026–4031 (IEEE, 2020).

Chakraborty, M. et al. Epilepsy seizure detection using kurtosis based VMD’s parameters selection and bandwidth features. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 64, 102255 (2021).

Tutuk, R. & Zengin, R. Epileptic seizure detection combining power spectral density and high-frequency oscillations. Int. J. Appl. Math. Electron. Comput. 11, 117–127 (2023).

Parhi, K. K. & Zhang, Z. Discriminative ratio of spectral power and relative power features derived via frequency-domain model ratio with application to seizure prediction. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 13, 645–657 (2019).

Kumar, P., Upadhyay, P. K. & Panda, M. K. SNSDeepNet: spike and non-spike detection in epilepsy. Eng. Res. Express 6, 035365 (2024).

Upadhyay, P. K. & Kumar, P. SeizureNet-BiLSTM: A hybrid deep learning framework for identifying ictal and interictal phases. In 2024 7th International Conference on Signal Processing and Information Security (ICSPIS), 1–6 (IEEE, 2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: P. Kumar, P.K. Upadhyay.; Methodology: P. Kumar; Formal analysis & data curation: P. Kumar.; Writing-original draft preparation: P. Kumar.; Writing-review & editing: P.K. Upadhyay; all authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kumar, P., Upadhyay, P.K. A hybrid optimization-enhanced 1D-ResCNN framework for epileptic spike detection in scalp EEG signals. Sci Rep 15, 5707 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90164-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90164-3

This article is cited by

-

Early warning score and feasible complementary approach using artificial intelligence-based bio-signal monitoring system: a review

Biomedical Engineering Letters (2025)