Abstract

Career women have varied responsibilities in society, and therefore, finding a balance among work, family, and personal life duties is becoming increasingly difficult. The literature explains that there is no one-size-fits-all standard for work-life balance. This study sought to explore ways of coping with family life and schooling among Ghanaian nurses and midwives pursuing graduate programmes without study leave. The paper was carved out of a more extensive study exploring female graduate students’ life experiences, combining work, family, and schooling. The study used an exploratory descriptive qualitative design through a purposive sampling approach to recruit 20 female nurses and midwives pursuing graduate programmes in three public universities in Ghana. The study obtained ethics approval from the Noguchi Memorial Institutes of Medical Research. Participants used social media, people in their social circles and religion to cope. Families, friends, church leaders, managers at work, and coursemates assisted in various ways. The support was in the form of money, help with household chores and childcare, granting off days, assistance with assignments, and counselling. Participants neglected the care of their husbands and children to concentrate on work and schooling. The graduate students watch movies, TikTok videos and listen to various music. Some forced themselves to sleep and as well, walk with loved ones to relief stress. Above all, participants relied on God via prayers and words of inspiration from motivational speakers. The authors believe that establishing and implementing family-friendly human resource policies targeting career women to empower themselves through graduate education will be beneficial.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For most organisations and their employees, finding a balance between work, family, and personal life duties is becoming increasingly difficult1,2,3. According to experts, there is no one-size-fits-all standard for work-life balance4,5. According to Allen et al.6, work-life is the degree to which an individual’s competence and pleasure in work-family roles are compatible with the individual’s life role priorities at any given time. When there is proper functioning at work, home, and personal levels with minimal role conflict, a balance in work, family, and personal life is expected7. Incompatibility between work and nonwork needs leads to conflict, and employees lack work balance8. According to research, employees who believe they do not have time for their personal lives are always tired and preoccupied at work9,10. People experience role conflict between work and family domains because the demands of the roles of work life and family life are inherently incompatible11.

Furthermore, overflowing unpleasant aspects of work into an employee’s personal life can result in job weariness, strained relationships with family and friends, diminished enjoyment, and increased stress12. It is all about balancing work, family, and personal life13, and achieving the balance requires building and sustaining supportive and healthy work environment that allows employees to balance work, family, and personal obligations, potentially increasing loyalty and productivity14.

Working parents have unique challenges because they are responsible for several duties15,16. Individuals who mix jobs and education face a variety of responsibilities in their personal and professional lives, which can interfere with their ability to maintain a healthy lifestyle and frequently result in work-family conflict17. For example, working mothers who belong to this category and seeking university education, in particular, are thought to be unable to maintain a healthy life balance. This is so because university education has higher stress and lower happiness levels18,19. Consequently, working women who study simultaneously are more vulnerable, as they juggle competing and demanding duties from work, education, and home20. However, little study has been done on how working women pursuing post-graduate education manage their well-being while managing work, academics, and parenting21. The scarcity of research on women who study while working makes it challenging to develop research-based human resource policies and practices22. As a result, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 4 and 5, which advocate for women’s empowerment via excellent education, would be jeopardised, particularly for women in paid work who desire to further their education to move up the corporate ladder23. Our research, therefore, adds to the continuing discussion about how SDGs might be used to further women’s empowerment worldwide1.

Many employees face a common dilemma: Balancing all the competing demands of work and nonwork roles while avoiding damaging spillover into their personal lives24. According to Duxbury and Higgins25 and Halinski and Duxbury26, one in every four Canadian employees reports that their work commitments interfere with their capacity to fulfil their domestic responsibilities27. The authors indicate that, women are more likely than men to report high levels of role overload and caregiver strain28. Women dedicate more time each week to nonwork activities such as child and elderly care and are more likely to be in charge of unpaid domestic chores29.

The work-life interface can be generally described as interwoven29,30,31. The situation arises because work activities can interfere with nonwork and personal activities, and so can nonwork life31. When people fail to achieve work-life balance29,30,31, they face many negative repercussions, which can be particularly damaging for women who shoulder significant domestic duties. When people cannot balance their jobs and personal lives, it can lead to less engagement with family members, limiting opportunities to spend meaningful time with them32. Individuals unable to achieve a work-life balance may also suffer from poor job and organisational performance7,32,33. Furthermore, when organisational structures force workers to stay and work long hours to prove their commitment and readiness for professional advancement, such demands can negatively impact individuals’ nonwork lives34.

Problem statement

Work-life balance is an endemic problem for many workers today. Multiple personal activities and leisure time are often scarce4. Changes in workforce composition, including the growth of dual-earner families, more women entering the workforce, and changing gender roles32,35,36, have made balancing work and nonwork life challenging. Research suggests that women, in particular, experience comparatively higher levels of struggle to balance work and life when attempting to navigate paid employment and unpaid socio-cultural responsibilities12,37,38,39. These life-ending problems will require proper and effective human resource policies that will pave the way for a healthier work-life balance to prevent some of these issues40. This empowerment can lead to improvement when working women receive adequate support1,14,29,41. Flexible work arrangements, supervisory and co-worker support, structured work-life schedules, and assistance from family members during the pandemic all have shown effectiveness as support mechanisms for navigating the conflicting demands of work, education, and family life1,29,38,42,43,44,45,46. The study explores how graduate student nurses balance their work life with work-life balance. Through the real-life experiences of the participants and their social support systems employed to manage and take care of their health, this investigation aims to posit meaningful recommendations to strengthen supportive frameworks47.

Methods

Research design

The study used an exploratory, descriptive qualitative design to investigate the phenomenon. The approach was deemed appropriate because an in-depth understanding of coping with family life, work, and school -life among females was required within the Ghanaian context48. In addition, the approach allows for flexibility in exploring a phenomenon of interest.

Study setting

This research was conducted in three3 universities located in Ghana. These settings were purposively selected based on the focus of the study, which was to understand female graduate nursing students’ coping mechanisms in juggling family life, work, and school in Ghana. These universities were the University of Ghana, University of Cape Coast, and the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. These Universities run Master of Philosophy (MPhil) in Nursing, Master of Science (MSc) and Doctor of Philosophy in Nursing programmes for nurses and midwives.

Population, sampling, and sample size

The study population included graduate student nurses from three universities in Ghana (the University of Ghana, the University of Cape Coast, and Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology). These universities were selected because they represent the top universities that provide postgraduate nursing education nationwide. The University of Ghana was especially prominent as it first established postgraduate nursing education in Ghana, which attracted a bigger pool of graduate student nurses than the others. The university was significant because it is an important historical birthplace for higher education in nursing and has a reputation that led to recruiting a larger portion of participants from there. In all, 17 participants were interviewed at this university. Thus, for ease and efficient utilisation of resources, the remaining participants were drawn from the other two universities, constituting two (2) participants from Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology and one (1) participant from the University of Cape Coast. The purposive sampling allowed for a thorough exploration of graduate student nurses’ experiences from diverse academic contexts while capturing a representative sample of the larger population of interest. Until data saturation was decided, recruitment provided a robust and adequate capture of the challenges of the student nurses who partook in the research49.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The study sampled graduate female student nurses with families enrolled in any of the three public universities in the country which run graduate nursing programmes. Graduate female students who were nurses enrolled in other programmes other than nursing or midwifery in the three selected universities were excluded.

Rigour

In ensuring the study’s trustworthiness, the authors established a cordial relationship with the participants preceding data collection. It was also done to put participants at ease so they could speak freely. Interviews were conducted face-to-face or via telephone as practicable. During the interviews, the researchers probed participants’ responses and sought clarifications to reaffirm their narrations50. The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim to increase the accuracy of participants’ narrations, further growing the findings’ dependability51. Participants had enough time during the interview to extensively share their take on the phenomenon52. Seven7 transcripts were sent back to participants who agreed to read their transcripts. The researchers ensured that the data collected were accurate, complete, and well interpreted and that findings denoted exactly what participants communicated during the interviews. The authors kept an audit trail, used verbatim quotations to denote what participants said, and tried to avoid biases and subjectivities in the study.

Ethics considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research (IRB 009/22-23). Research information on this study was communicated and explained to research participants, and informed consent was obtained before data collection. The study followed all methods per the relevant guidelines required to satisfy the demands of the Helsinki Declaration. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any point after notifying the researchers without fear of punitive measures or harm. Anonymity was maintained by assigning participants special codes, and confidentiality was maintained by ensuring all audio tapes, transcribed data, field notes, and documented information participants gave were stored and encrypted. Access to the data is restricted to the research team alone. The researchers anticipated the risk of psychological discomfort associated with situations of ineffective coping and made prior arrangements for a Clinical Psychologist to provide mental health support for the participants. However, no psychological therapy was offered as no one broke down emotionally during the interview.

Data collection

Data was collected through individual in-depth interviews from August to October 2021. To ensure the trustworthiness of the data, the interviews were guided by a set of questions the researchers prepared beforehand. The researchers contacted the class representatives and informed them about the study’s objectives. Their assistance was sought to help recruit participants for the study. Before the data was collected, the researchers first established rapport with participants. Participants who consented to participate in this research were engaged in face-to-face and telephone interviews. Each interview lasted between 30 and 60 min. All the interviews were conducted in English and audio recorded with participants’ permission. During the interviews, participants were asked to share their coping strategies for balancing work and nonwork divide. Some questions asked included: What does work-life balance mean to you? How do you switch off among the three? Please tell me about the changes in your work, education, and family since you started this programme. What currently helps you achieve your work, education, and family balance? Data collection ended at saturation when no new concepts relevant to the study objectives emerged53.

Data analysis

Audio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim54, as the transcriptions began after the first interview and continued concurrently with subsequent data collection55. Data were processed anonymously with ID numbers to ensure the confidentiality of participants. All authors read the transcripts several times to familiarise themselves with the data. All authors then coded the transcripts independently using Reflexive Thematic Analysis56. The researchers analytically explored the data to find meaning-based patterns to provide a coherent interpretation of the data grounded in the study56. The researchers actively interpreted the data through their cultural and social backgrounds as working Ghanaian graduate nursing students with family responsibilities. NVivo computer software version 11 was used to manage the data57. All authors reviewed the coded transcripts separately. Similar codes were grouped to form subthemes, while similar subthemes were grouped to form the main theme. The authors met to review the themes and subthemes that were generated until a consensus was reached on the generated themes and subthemes.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants

A total of 20 female graduate nursing students studying in three public universities in Ghana and pursuing graduate programmes in nursing and midwifery were recruited to participate in the study. Table 1 details participants’ socio-demographic characteristics. All the participants interviewed were working nurses and midwives with other family responsibilities. All the participants were females with senior nursing and midwifery positions.

The main theme and subthemes generated from the data

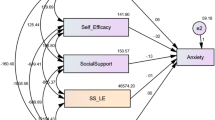

The data generated one major theme, five subthemes, and three sub-subthemes. The central theme, coping strategies, had the following subthemes: social support (with three sub-sub-themes: family support, support from friends and support from significant others); family compromising, engagement in recreational activities, rest and sleep, relaxation, and prayer and inspiration. Figure 1 details the central theme and subthemes generated from the data.

Coping strategies for juggling family, work, and academic life

Graduate students are exposed to various demanding and stressful circumstances requiring coping strategies and preventing burnout. This theme elaborates on the different mechanisms the female graduate students adopted to help them manage the challenges associated with the stressful academic environment, work, and family life. A key mechanism used was social support. The participants’ family members, especially their spouses mothers, siblings and nieces supported them in various ways. Friends and significant others such as church members, work colleagues and managers, nannies, drivers and house helps also provided varied support.

The support received included cooking for them and taking care of their children, assisting them financially, assisting them with their assignments, and explaining complex subjects. They were also assisted in searching for materials online, encouraged, and prayed for to succeed. The participants said they received advice, had flexible work schedules, and had people covering for them at their workplaces. The support offered by nannies, house helps, and drivers was paid for, but all other support was provided for free.

Other coping strategies participants adopted included listening to music, going out with their children, sleeping, watching movies, watching TikTok, and listening to inspirational messages on YouTube. Subsequently, the five sub-themes generated under this theme have been described.

Social support

Most female graduate students concurred that the assistance from various sources helped them get through their academic work. Social support was either paid for or provided for free. This occurred in numerous ways, including from families, friends, and significant others. Some of the participants’ mothers, siblings or nieces lived with them to handle household chores and take care of their children. This subtheme has three sub-subthemes.

Support from family

Family members of participants provided most of the support participants obtained. Close family members, such as mothers, husbands, and siblings, offered much support. Some moved to live with participants to cater for their children and help with household chores.

“I gave birth before coming to school, and luckily, my mum was around, so she is taking care of the child. My mum has been very helpful and a very strong anchor throughout. Sometimes, when I go to work, and my husband is around, he cooks and leave some of the food for me. He does not stress me with issues like ‘I am hungry, get me this or that’; he does it when he has the energy to do something for himself”. (P2).

I get support from my mother and from my husband, so, yes, they help me with the children when they are back from school. Regarding the family, apart from the four kids with a mind of their own, my husband and mother have been very supportive. (P4).

Aside from the nuclear family, other extended families’ support was sought as some people called on their nieces to offer help in their abscence.

“… I asked for assistance from my mother. But my mother fell ill, so I had to rely on a relative, so I had to bring in a niece who had completed senior high school (SHS) and came in while I was away. But all the same, waking up in the morning to see to the kids and other stuff before coming to school was not easy at all”. (P1).

Some had much support from both nuclear and extended families in the form electronicgadgets like tablets and laptops.

“My husband and my siblings are also supporting. I remember complaining about my laptop being heavy and sometimes giving me back pain. So, within 24 h, my sister sent a tablet through a delivery guy to bring it to me. I can transfer some of my things to the tablet to read them. And recently, I was here when my younger brother also brought me a MacBook Pro laptop…for me to use so that I stop using the old laptop, which I complained had been heavy and I have to carry at the back since I’m not driving. So that is the family’s supports”. (P7).

Again, most husbands understood the need for their wives to undertake the programme and offered them emotional support through words of encouragement. Others had their husbands supporting them with the care of their children, cooking, and helping them with their daily activities.

“… it is the support from my husband that has been my backbone, so far, so good from the beginning up to this stage. If I didn’t have such support from my husband, I would have stopped the school a long time ago” (P8) “… and then my husband; he’s been very, very supportive; paying my fees and making sure that I’m always doing my assignment” (P3).

“Yeah, but my husband has been of great support as well; financially and emotionally, he’s been there for me” (P9).

“I’m also getting financial support from my husband, and my husband and I compliment each other. My husband calls in between to check up on me and assist the kids with their homework and other chores. It wasn’t a burden to him [my husband] because he knows it’s for a while, and they will have me back to play my role fully again…. (P11).

Some graduate nurses believe that making the family aware of their plans to pursue higher education gave them family support.

“With my family, I had to involve them and make them understand that I need to pursue my career, so they also supported me by allowing me to bring in an external person to help all of us”. (P13).

“… without the support systems, it would have been challenging, for instance, at home. My husband plays a very supportive role…” (P15).

Support from friends

Participants also mentioned other forms of support from colleagues and friends stepping in to fill the gaps at the workplace and home when they leave for school. Colleagues/friends help their children with their personal upkeep and homework. Again, participants were aided through their programme with the support of their colleagues through group discussions and internet searches.

“I receive encouragement from friends to forge ahead…”(P10).

“I have my friends who call to encourage me; …though not physically, but they will call to check up on you. How are you doing with your work? Finish hard; we are praying for you. So, I think friends are helping.” (P16).

Some friends also provided participants with emotional support, and participants looked at others and got encouragement from their situation.

“I have a colleague who has been a very good friend; she encourages me. On days that I’m so down, she will always encourage me, oh, you can make it; let’s try and focus.” (P18).

Friendship support also had to do with looking for articles, helping them complete an assignment, or looking for a model to inform their study.

“I remember I had to look for a theoretical framework for my study, but I was not getting one. So, a friend of mine looked for one for me. When I do not understand something, we discuss it, and she explains things clearly. She helps me search for articles online. Other friends have also sent me course materials via WhatsApp and email. I had a 48-hour term paper to submit. Not that I couldn’t do it, but I called some friends because of the work’s timing, volume, and gravity. One was from human resource management. I have a Liberian friend who did that, so I immediately called him, and he assisted me. My friends have been supportive (P17).

Those with technological challenges fell on friends to get them directions on searching for materials online. They also reciprocated the gesture and described the support as a give-and-take affair.

“I also have other colleagues sometimes if it is about technology or maybe you are looking for other things on the internet, I ask my friends how we go about this, and sometimes we teach each other because I might know something that you might not know so it’s like give and take.” (P19).

In addition, coursemates of participants encouraged and advised participants to continue with their programme. Graduate students also sought clarification from colleagues on previous classes or lectures, especially the ones where the participants were absent. Other assistance was in the form of covering for other students during group assignments. Downloaded articles and shared with colleagues for study.

“… initially when I came, I didn’t know anybody, but as time passed, I got to know a few friends, and we formed a discussion group. There are times we need to stay on a bit before going home. One thing that stood out as a group was that we were each other’s keeper and supported each other with assignments. We shared information among ourselves, and our colleagues accommodated on campus, especially one of the guys, was helpful. He will search for articles we need to read, download, and share them with us. So, I think the networking I did helped me a lot”. (P12).

“…I have a colleague who is a friend, and she encourages me. On days that I’m so down, she will encourage me, oh, you can make it; let’s try and focus. Also, others have passed through that; I look up to them.” (P10); “When I don’t understand something, I call on a course mates to get some clarification” (P8).

“… in school, we have constructive group discussions; even if one missed a lecture, the group can explain what was taught as though one was present. There are other times that colleagues will also record it for me when I miss a class” (P5).

Support from significant others

The significant others in this study refers to nannies drivers, highed teachers, house helps, church leaders and members, faculty membe to Even though most of the support systems were unpaid, participants also accessed the services of nannies drivers, teachers, and house helps to support their children’s upkeep and the home whenever they could not make time for these core duties. Furthermore, faculty members of participants’ schools supported participants emotionally and psychologically by words of encouragement.

“… at home, I have a nanny to help while I’m away, and by so doing, I can make some time to concentrate on my studies and meet deadlines. I also get someone to do the marketing, which is done monthly”.(P14).

“…at some point, when I took the children to the nearby school at some point, I had to rely on a few friends to pick up my kids from school because my kids were at first not in Accra, so when they came to Accra, they could not manoeuvre their way around, so I had to get some help in that regard” (P1).

“… sometimes I call a driver to pick the children up from school. …the days I close late, the driver brings them. I also engage the services of a carer to take care of them. I have a teacher who teaches them, and she can stay with them until I return. I once told her [the carerer] I had been given an assignment, so I had to finish up before I come, and I had give her instructions and then she handled them till I came back. That has been a good support. (P20).

Also, in the participants’ workplaces, their managers were understanding and though the participants had no study leave, they granted them flexible work schedules, and days they were not available, they instituted mechanisms to cater for their absence.

“At work, my in-charges knew I was in school, so I also received some support from them … (P17).

“Then for my workplace as well, they’ve been very supportive. Nobody will give you that opportunity to go to school. You went away for about three years, you are coming back, and you still want to go to school, and they allow you to go. So, they’ve been supportive, giving me the time to go and then come as and when I get time” (P2).

My immediate boss, whom I report directly to, is quite understanding. She is a mother of 12 and likes education, so she is quite understanding. So, for work, yes, she understands, although it’s quite stressful. But my boss is very understanding”. (P18).

“With work, though I didn’t get study leave, there was some form of arrangement for me, which was a bit flexible. I go in to help when I’m less busy. I work at the nursing administration where there are no weekend duties, but as and when they need my help, I go there occasionally on Fridays to support…” (P5).

Some of them receive encouraging words from their bosses that urge them to move on. For example, this student pursuing a PhD had this to say about her principal.

… my principal will always say that [mentions her actual name], I am looking up to you to finish so that I can also say that I have a staff who is holding a PhD in the School (P6).

According to some participants, what kept them going is the support and encouragement they get from some of their supervisors and other lecturers. Most supervisors allow students to share their frustrations with academic work and inability to meet deadlines. They are assisted with solutions to these challenges.

“… my supervisor is very good. You know, some supervisors give you deadlines, give you pressure, but she, when she doesn’t see me, she knows I’m serious, so when she sees me, she’ll ask how it is going, and say I know because you’ve not come you have one or two, but I know you will go through. Anytime I call her, she is ready to answer me, and it makes me relieved that she won’t give me plenty of articles to read, which frustrates me. I would rather bring out whatever I have; she will discuss it with me. And then, sometimes, if she feels there is a better person to go and see, she will direct me to the person. She’s always encouraging me. My supervisor, I’m very proud of her. So, she is one person who has also been encouraging me to continue” (P13).

“… I think my supervisor too has been of great help to me because when I’m delaying, and I’m not checking up on her through calls, she’ll call and find out what is happening; and because she’s a woman and has been through motherhood as well, I think she understands me. She encourages me to push to do with it” (P18).

The participants also received physical and emotional support from their institutions’ faculty members, where they offering their programmes. The participants described the faculty as understanding, reasonable, and friendly. Some faculty encouraged students to look at the benefits they will get at the end of their programmes despite the stresses associated with it and finish their programmes.

“… the support from school; the lecturers have been very supportive, and I commend them. They are very understanding, they know the stress we are going through, and although the programme is packed, they are very reasonable, especially meeting some assignment deadlines, and for me, that is also a form of support” (P6).

“…what I can say about where I am schooling is that they are friendly, understanding, and make you feel at home. A few months ago, I got sick, and the way and manner the issue was handled makes me feel that I have people I can look out for. It came from the lecturers, HODs, colleagues, mates, and everybody. Emotionally, they will call you and find out how you are faring daily. How am I coping? Am I experiencing any complications from the surgery? Anything they need to know about my life. They called to find out, and it was so refreshing to know that apart from your family, somebody also cares about you”. (P3).

“… and then some of my lecturers, especially those that we have in our pediatric course, as our lecturers, they are always encouraging us. They always tell us that, for now, see it as you are stressing, but at the end of it, you will enjoy” (P14).

Participants’ church leaders also had varied ways of assisting them, including providing internet access and helping with their project work.

“My Head pastor has very good internet in the house, so sometimes she will do video call and tell me she wants to see me because it’s been a while, then I will tell her, oh my work and she will say come to the house I have internet, when you come you can access it so that we can talk over your work. So when I went, I went with my laptop and put in the password. As I was talking and she was also learning, so as we were talking and doing my work, she was even contributing to my work, so for them, that is the small thing they can do to assist”. (P9).

Family compromise

Graduate students renege on their duties towards their families to satisfy other commitments from their jobs and academic life. Some sacrificed their physical, emotional, and even marital roles towards their family, especially their spouses, during schooling. However, video and audio calls reached their families whenever they left for school.

“…I feel my husband is the one who is not getting any attention from me; he is the last person getting my time. Seriously, he has been neglected the most in the house. For my children, over the weekend, I make sure that we are together, but for my husband, I don’t know, but I think that he understands, so once a while I try to pay attention to him” (P20).

“I contact my family virtually; we do video calls, but personally, going there is difficult unless we vacate. Then I can get time for them, so since we reopened school, I have not been able to meet with them, but I communicate with them a lot. Every day, afternoon, and evening, I communicate with them, but to have me personally with them, no… but I wish I could spend time with them as well. I miss them badly (P11).

“…and then, demands from your partner, because there could be times that your partner will need you emotionally and you realise that if you are at Kwahu working, or I’m in Cape Coast, there is no way he can have my attention okay, so you ignore it” (P7).

Some participants believe that people make comments upon realising that they leave their children behind for others to care for them and sometimes this break them down. Some also ignore their children to concentrate on academic activities and deprive them of their love.

“So, my family life, leaving your children; sometimes the one taking care of them, mostly, maybe she goes to town and comes home; she doesn’t come on time. So, when you go home, people see you, and the way they approach you, they ask you: Why have you left your children? They are too small, and you are staying somewhere. It’s like you don’t care. The way they say it, they will make you feel bad as if you are not responsible” (P6).

A participant felt her child cries whenever she was ready to work, making her shout at the child. She also added that she ignores her husband until she ensures she is done with any work she brings home.

“my son, for instance, most of the time I needed to do my work; that was when he wanted to cry. So, you know, at times, I will shout at him to keep quiet, to stop crying. Or maybe he’s crying, calling for my attention, and I’m also writing something significant that if I leave, I will forget the point, so definitely, he has to cry small so that I can finish writing. Then my husband too, if I have an assignment to finish, I have to finish before any other thing can follow” (P 16).

Some participants narrated that their children refuse to eat because of their absence at home and will resort to crying.

“I am mostly away from my family, which affects my daughter whenever I’m in school. She wouldn’t eat and she will be crying, ‘Mummy, why are you not with us? ‘, ‘When are you coming’? I miss you! Those were some of the few moments that I miss my family”. (P11).

For some graduate students, their children now do things they would not have done if their mothers were to be with them in the house. Younger children learn to prepare their food, wash their things, and help with other household chores that their mothers mostly do.

“…I think my children are learning to adapt to my absence. I am their teacher when they come home from school. I assist them to do their homework. I learn with them such that even in my absence, when there is the need for them to learn or have a class test, they open the textbook, tell me the book, tell me the page, and I can help them, and I can question them because I have read it. Now they have learnt to prepare their breakfast and fry their eggs. They can now cook noodles (indomie) with sausage. They are learning things that if mommy were around, they wouldn’t do. While washing their clothing, they must wash panties, soaks, and handkerchiefs. And I taught them how to wash the bathroom. Sometimes, I get home and am exhausted, so we do the bathroom and the gutters behind the house. So, I remember one time when I couldn’t work with them; they washed the bathroom all by themselves. And then they assisted their father to wash the gutter behind the house….” (P2).

Engagement in recreational activities

Some graduate students said they release stress by watching movies, listening to music, and using social media. Others resort to outings with family and friends and spending time with children in schools and playgrounds to relax their minds from the stresses associated with academic work. Some also relax by engaging in other programmes that take them out of their immediate surroundings where they can relax, walk around, and eat what they like.

“… I volunteer for Operation Smile, so now when I go for those workshops, I just use that period to relax. When I go, I sleep in a hotel, so it is not stressful over there; I also eat what I want there, and if I want to walk around, I do that. Operation Smile takes about a week and a half, which is about ten days, and even though the work is tedious, you get to meet many people; it is also a new environment. You have fun, so those are the ones I use as relaxation, until recently when I organised my friends and said no, we cannot go on like this, so once a while we go out and have some fun” (P17).

… sometimes if my husband is around, … during the weekend, we can travel together with the kids and then maybe go to have fun and come back, …and then personally, too, I take them to a playground; they go and play, and then me too I can sit around and then have fun. Because I also handle a school (Montessori) … so sometimes I go around the kids, you know it’s interestingly when you have little kids around” (P3).

While some moved out of their houses to relax elsewhere, others stayed indoors to watch movies, and the movies some participants watched were mostly funny local movies.

“… I watch movies for maybe an hour or two. … I would rather stay indoors, watch movies one or two, and then return to work. So, sometimes, I chat and take some time to talk with friends or my husband. Then I watched movies as well (P8).

“The movie, I like watching the local movie, be it Nigeria or Ghanian, the funny, funny one, I don’t usually watch the Ghallywood, Nollywood is the other local one, not the elite, elite ones. Those are funny, and they act naturally. In Nigeria, they are very good actors, so it makes you feel at home, the comedy, for the music, when it comes to the music, all the … be it hiplife, reggae, gospel, I like the gospel the worship type it is kind of, I mean it is cool. It brings your spirit to another level so you can relax and sleep off”. (P1).

A participant said she watches television and relaxes but can only do that when her baby sleeps.

“But I will mostly relax by watching television and taking time off to release stress. Mostly when my baby is asleep, that’s when I get much of the time, but once he’s awake, all other things cease” (P 14).

Rest, sleep, and relaxation

Both physical and emotional exhaustion associated with academic work usually leads participants to react through various approaches, with rest and sleep being one intervention. Participants indicated that they relax when and wherever they get the chance. While some participants relax at the salon, others pack their cars along the road and nap when driving. Again, participants forced themselves to sleep by turning off their radios and ensuring they were in a quiet room. Some also listen to music and watch funny videos to relieve tension.

“Saturdays, I take time off to go to the salon. I feel more relaxed at the salon because I normally go to meet a queue and take time to relax there. I then come back home to prepare for Sunday. There are times the kids are already asleep before I get home so quickly, I do what I am supposed to do, i.e., pack their bags, their lunch, whatever is needed for the next day, take a nap for an hour, if there are any assignment, I do them”. (P15).

“… hmmm, switching from one to the other hasn’t been easy. There is no exact time that you can relax. I usually try to find strength from within, and sometimes, after being close to work, I listen to music or watch funny videos on my way home. So, this is my way of relaxation because as soon as I get to the housework, there is no devoted time for relaxation”. (P18); “I try to sleep small, and get up and continue” (P 12).

Some graduate students said they intentionally use the scarf to cover their faces and force themselves to sleep, nap, refresh, and return to work.

“Sometimes during exams, you realise that you have not learned so much and that there is no space for what you want to read to go; if you get about one hour of sleep, you will be refreshed and return to continue the studies. If I want to sleep and the sleep is not coming, I must force myself to sleep. I have this scarf. I use it as a face shield because I don’t have a face shield, tie my eyes, tie the knot at the back of my head, and cover myself with a cloth. If it is evening, I turn off the light to get that darkness, and then I sleep. If it is in the hall, I am not alone there, so I can’t just go and put off the light. So, putting on the shield also gives me that darkness to nap or sleep for a while. And once I am up, I get refreshed to continue with whatever I was doing or wanted to do”. (P1).

Some intentionally take public transport to sleep while on board from school to the house. Some resort to watching television, and others force themselves to sleep by using a cloth to cover their eyes.

“…I pick public transport, at least I can relax a little when on board, sometimes I do off in the car, which is very helpful, by the time I get home, I will have had some rest even though it will not be like sleeping on a bed”. (P 7).

“I relax by watching my television, taking time off to release some of the stress. Mostly when my baby is asleep, I get much of the time, but once he’s awake, all other things cease” (P3).

Sometimes, I don’t turn on the radio when I feel tense or have a headache. I make sure the place is quiet enough. I wear my clothes to cover myself, or sometimes I wear a small scarf to tie my eyes. I use it as a face shield, so when the place is already dark, I force myself to sleep by the time I realise I am already asleep. So, if I find it challenging to sleep, these are some of the things I do, so that is my remedy (laughing) (P19).

Prayer and Inspiration

Participants were empowered to go through the programme through prayers and inspiration from their churches and other sources. Listening to inspirational messages from pastors and church members and using social media (YouTube) were some ways participants got inspired.

“Like I said, you can’t do it all by yourself, so I have people at church who help me out with prayers both at home sometimes and at church as well” (P4). “I pray about everything that I do, even here I pray to keep me go through the programme” (P 11).

Partners of religious leaders’ encouragement and inspirational messages on YouTube helped some participants cope.

“I remember my pastor’s wife occasionally will call and ask me how I am doing and tell me we are praying with you, and sometimes before we end the conversation, she will offer a word of prayer”. (P7).

“Just the inspirational messages that I always listen to. They keep me moving. That is what keeps me moving. I am always there. Whenever I am sad, I go to YouTube. I am always there to listen to inspirational speeches. Something to motivate me. When I listen, when I hear those things, it keeps me moving” (P13).

Discussion

This study explored working graduate female students’ experiences of juggling work, family, and school roles because of their enrolment into graduate (Master’s and PhD) degree programmes. The results provided a valuable perspective on how working student mothers in different career stages balance their highly demanding roles as students, mothers, and professionals. Graduate students were exposed to challenging and stressful situations that necessitated coping skills to avoid weariness. The main finding of this study looked at the numerous mechanisms used by female graduate students to cope with the challenges of a stressful academic environment. The participants’ spouses, family members, friends, church elders and members, professional colleagues, and significant others were their sources of support. Cooking for them and caring for their children, paying their school fees, supporting them with their assignments, explaining difficult subjects, assisting them with finding resources, encouraging them, and praying for them were all examples of the support received. This finding aligns with the findings from previous studies1,43,58,59, which discovered that support systems or coping skills hugely facilitate balancing work, school, and family life. The support aims to lighten the burden of the weight of events that one has to deal with; as such, the graduate students in this study got their burdens in all three areas lightened with the support systems they got60.

Another important set of findings is related to the massive social support participants received. This finding corroborates with29. The participants achieved enormous success in their academic pursuits because of the help they received from various sources, as found in earlier research28. Social support was paid for or unpaid for, depending on the source of help; help for participants in this study generally came from family, friends, significant others, or both, thus unpaid. Participants’ mothers and siblings resided with them to help with house chores and childcare. Support mainly came from their family members61.

Physical, mental, and financial help were all free (unpaid). Close family members such as moms, husbands, and siblings rendered most of the help62. The extended family system still works very well in Africa, which might explain why the participants got help for free from their family members. Husbands recognised the need for their wives to participate in the school programme and thus willingly offered to help them go through school. Husbands also helped children with their assignments and contracted people to shop for the house63. Help from husbands additionally came in the form of payment of fees and caring for children while wives were away in school studying, cooking, and feeding children, as well as helping children with activities of daily living64,65,66. Help from husbands in this study was seen as a phenomenal observance and an exciting finding, as power is usually not equally shared between husbands and wives in many homes within the African context. Again, husbands within the African culture often find it challenging to perform roles perceived to be the preserve of wives, so finding husbands perform such roles on behalf of their wives is quite interesting67.

Friends are a great asset as they can complement us in many ways39. Participants harness assistance from colleagues and friends who took up some of their roles at work and home when they left for school. Colleagues and friends assisted participants’ children with personal maintenance and homework. Participants were supported in completing their program with the help of their peers through group discussions and internet searches.

Participants received emotional support from certain friends68 and looked to others for encouragement in their difficulties. Friendship support also included finding papers online, assisting them with assignments, and seeking a model to use in their research69. Participants received emotional support from select friends and sought encouragement from others. Finding papers for them, supporting them with homework, and looking for a model to utilise in their research were all examples of friendship assistance. Participants described the faculty as understanding, moderate, and friendly63. Some friends advised students to focus on the rewards they would receive at the end of their programmes despite the stress they faced.

Furthermore, dealing with academic work was made possible with the help of classmates. Some students were inspired to continue their studies after receiving encouragement and advice from their peers70. Graduate students also sought clarification from their peers on past classes or lectures, particularly those in which they were absent. Other forms of aid included filling in for other students during group assignments. Participants’ church leaders who doubled as friends aided them in various ways, including giving internet access and assisting them with their project work71,72.

Another exciting discovery of this study is the compromises participants made to enable them to go through school73. Graduate students neglect their responsibilities toward their families to meet their other obligations from work and school74. During their schooling, several people relinquished their physical, emotional, and even conjugal roles toward their families, particularly their husbands. When they left for school, though, they used video and voice calls to communicate with their families. Some participants believe that the statements individuals make when they realise they are leaving their children in the hands of strangers can occasionally tear them down. However, some parents neglect their children to focus on academics, depriving them of attention and love. Some graduate students’ children performed activities (such as doing their laundry, mowing grass and cleaning around the home) that they would usually not have done if their mothers were around with them at home.

Recreational activities were beneficial to participants in this study75. Participants got involved in various recreational activities, such as watching movies, listening to music, and using social media as coping mechanisms. Others relaxed their minds by going out with family and friends and spending time with children in schools and playgrounds to escape the demands of academic work76. Others unwind by participating in various activities that take them away from their immediate surroundings, allowing them to relax, wander around, and eat whatever they like47. While some people left their homes to relax in other places, others stayed inside to watch movies, many of which were comedic local films.

Rest, sleep, and relaxation were also great coping strategies for participants in this study77. Due to the stressful nature of academic work, participants mainly used rest and sleep to rejuvenate themselves78. Participants unwind whenever they had the opportunity to do so. Some participants unwound at the salon, while others loaded their cars and drove long distances while napping79. Participants forced themselves to sleep by turning off their radios and ensuring they were calm. Some graduate students notably used a scarf to cover their faces and push themselves to sleep so they could return to work revitalised. Again, some people de-stress by listening to music or watching funny videos80. We had those who purposefully used public transportation to nap while on board the bus from school to the house or home81.

Prayer and inspiration were the bedrock for coping in this study82. Participants felt encouraged and supported by the prayers and inspiration they received from their churches and other sources; they were inspired to keep going by listening to encouraging remarks from pastors, church members, and social media (YouTube). Participants would properly have terminated or stopped their schooling without prayers and inspiration due to the overwhelming stress school work gave them80.

Conclusion

The present study explored the views of graduate female students to understand how they balance their work, studies, and family life, as well as the available support systems they use. The results provided a valuable perspective on how working student mothers in different career stages balance their highly demanding roles as students, mothers, and professionals. The participants’ spouses, family members, friends, church elders and members, professional colleagues, and significant others were their sources of support.

Recommendation

The authors recommend that the Ghana Health Service and Ministry of Health establish and implement family-friendly human resource policies that target working women who want to empower themselves through university education. This will help female nurses and midwives have a stress-free experience in navigating the tightrope of family life, work, and education.

Limitations

The study was restricted to only three public universities in the country without involving other public universities. This is because these universities were the only ones offering graduate nursing education at the time of the study. However, future studies should examine how nurses and midwives who travel out of the country for higher nursing and midwifery education cope with family, work, and schooling.

Data availability

Transcripts from which this manuscript was crafted are available on request from the corresponding authors.

References

Boakye, A. O., Mensah, R. D., Bartrop-Sackey, M., Muah, P., Boakye, A. O. Juggling between work, studies and motherhood: The role of social support systems for the attainment of work-life balance. sajhrm.co.za. 2021.

Journal, G., Bouwmeester, O., Atkinson, R., Noury, L., Ruotsalainen, R. Work-life balance policies in high-performance organisations: A comparative interview study with millennials in Dutch consultancies. journals.sagepub.com. 2021;2021(1), 6–32.

Alby, F., Studies MFH, 2014 undefined. Preserving the respondent’s standpoint in a research interview: Different strategies of ’doing’ the interviewer. Springer. 2013;37(2):239–56.

Kinman, G. & Jones, F. A life beyond work? Job demands, work-life balance, and well-being in UK Academics. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 17(1–2), 41–60 (2008).

Johari, J., Yean Tan, F. & Tjik Zulkarnain, Z. I. Autonomy, workload, work-life balance and job performance among teachers. Int J Educ Manag. 32(1), 107–120 (2018).

Allen, T. D., Herst, D. E., Bruck, C. S. & Sutton, M. Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: a review and agenda for future research. J Occup Health Psychol. 5(2), 278–308 (2000).

Deshmukh, K. Work-life balance study focused on working women. Int J Eng Technol Manag Res. 5(5), 134–145 (2020).

Dousin, O., Collins, N. & Kler, B. K. Work-life balance, employee job performance and satisfaction among doctors and nurses in Malaysia. Int J Hum Resour Stud. 9(4), 306 (2019).

Hameed, A. & Khwaja, M. G. The impact of benevolent human resource management attributions on employees’ general work stress, with the mediating influence of gratitude. J Gen Manag. 27, 03063070221130872 (2022).

Balkin, D. B. & Werner, S. Theorising the relationship between discretionary employee benefits and individual performance. Hum Resour Manag Rev. 33(1), 100901 (2023).

Sirgy, M. J. & Lee, D. J. Work-life balance: an integrative review. Appl Res Qual Life. 13(1), 229–254 (2018).

Cho, Y. et al. Women leaders’ work-life imbalance in South Korean companies: A collaborative qualitative study. Hum Resour Dev Q. 27(4), 461–487 (2016).

Lafferty, A. et al. Colliding worlds: Family carers’ experiences balancing work and care in Ireland during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Soc Care Community. 30(3), 1133–1142 (2022).

Barber, L. K., Conlin, A. L., Santuzzi, A. M. & Larissa Barber, C. K. Workplace telepressure and work-life balance outcomes: The role of work recovery experiences. Wiley Online Libr. 35(3), 350–362 (2019).

Guy, B. & Arthur, B. Academic motherhood during COVID-19: Navigating our dual roles as educators and mothers. Gend Work Organ. 27(5), 887–899 (2020).

Graham, M. et al. Working at home: The impacts of COVID-19 on health, family-work-life conflict, gender, and parental responsibilities. J Occup Environ Med. 63(11), 938 (2021).

Mjoli, T. & Ruzungunde, V. S. An exploration into the role of personality on the experiences of work-family conflict among the mining industry personnel in South Africa. Acta Commer. 20(1), 1–11 (2020).

Nicklin, J. M., Meachon, E. J. & McNall, L. A. Balancing work, school, and personal life among graduate students: a positive psychology approach. Appl Res Qual Life. 14(5), 1265–1286 (2019).

Soysa, C., Mindfulness, C. W. 2015 undefined. Mindfulness, self-compassion, self-efficacy, and gender as predictors of depression, anxiety, stress, and well-being. Springer. 2015;6(2):217–26.

Smithson, J., Gender, E. S., Organization, W. & 2005 undefined. Discourses of work-life balance: negotiating ’genderblind’ terms in organisations. Wiley Online Libr. 2005;12(2).

Sharkey, J., Caska, B. Work-life balance versus work-life merge: A comparative analysis of psychological well-being in today’s workplace. 2019.

Shujat, S. impact of work-life balance on employee job satisfaction in private banking sector of Karachi. IBT J. Bus Stud. 2011;7(2).

Odera, J. Human JMS development goals and, 2020 undefined. SDGs, gender equality and women’s empowerment: what prospects for delivery. library.oapen.org.

Akanji, B., Mordi, C., Simpson, R., Adisa, T. A. & Oruh, E. S. Time biases: exploring the work-life balance of single Nigerian managers and professionals. J Manag Psychol. 35(2), 57–70 (2020).

Duxbury, L., Higgins, C. Something’s got to give: Balancing work, childcare and eldercare. University of Toronto Press; 2017 [cited 2024 Sep 28]. Available from: https://books.google.com/books?

Halinski, M. & Duxbury, L. Workplace flexibility and its relationship with work-interferes-with-family. Pers Rev. 49(1), 149–166 (2020).

Duxbury L. CHC justice and, 2015 undefined. Identifying the antecedents of work-role overload in police organisations. journals.sagepub.com. 2015;42(4):361–81.

Draper-Clarke, L. J. & Edwards, D. J. A. Stress and coping among student teachers at a South African university: An exploratory study. J Psychol Afr. 26(6), 491–499 (2016).

Andrade, C., Continuing MMJ of A and, 2017 undefined. Adding school to work-family balance: The role of support for Portuguese working mothers attending a master’s degree. journals.sagepub.com. 2017;23(2):143–61.

Chummar, S., Singh, P. & Ezzedeen, S. R. Exploring the differential impact of work passion on life satisfaction and job performance via the work-family interface. Pers Rev. 48(5), 1100–1119 (2019).

Martínez-León, I. M., Olmedo-Cifuentes, I. & Sanchez-Vidal, M. E. Relationship between the availability of WLB practices and financial results. Pers Rev. 48(4), 935–956 (2019).

Annor, F. Work-family conflict: A synthesis of the research from cross-national perspective. J Soc Sci. 12(1), 1–13 (2016).

De Villiers, J., Kotze, E. Work-life balance: A study in the petroleum industry. SA J Hum. Resour. Manag. 2003;2(1).

Vasumathi, A., Arun P, of PRIJ, 2021 undefined. An empirical bivariate study on the work-life balance of women labourers with special reference to tannery industry. inderscienceonline.com.

O’Donnell, M., … LRSIJ of, 2019 undefined. An expanded holistic model of healthy workplace practices. emerald.com.

Mos, B., Bandar N Abdullah, … SSJ of C, 2018 undefined. Generation-Y Employees and their perceptions of work-life balance. Publisher.unimas.my.

Chinomona, E, Economics EMIB &, 2015 undefined. Women in action: Challenges facing women entrepreneurs in the Gauteng Province of South Africa. clutejournals.com. 14(6).

Studies KLKJ of F, 2020 undefined. Women’s work-life balance strategies in academia. Taylor Francis. 2020.

Mordi, C., Simpson, R. Time biases: Exploring the work-life balance of single Nigerian managers and professionals. 2019.

Bianchi, S., Family MMJ of M and, 2010 undefined. Work and family research in the first decade of the 21st century. Wiley Online Libr. 2010;72(3):705–25.

Resource LFTIJ of H, 2014 undefined. Supportive work–family environments: implications for work-family conflict and well-being. Taylor Francis. 2013;25(5):653–72.

Sharkey, J. Review BCDB, 2020 undefined. Work-life balance versus work-life merge: A comparative and thematic analysis of workplace well-being. dbsbusinessreview.ie.

Maxwell, G. A., Mcdougall, M. Juggling between work, studies and motherhood: The role of social support systems for the attainment of work-life balance. sajhrm.co.za. 2004;6(3):377–93.

Johari, J., Tan, F. Educational ZZIJ of, 2018 undefined. Autonomy, workload, work-life balance and job performance among teachers. emerald.com. 2018.

Jones, F., Kinman, G. A life beyond work? Job demands, work-life balance, and well-being in UK academics. 2008.

Emslie, C. & Hunt, K. ‘Live to work’ or ‘Work to live’? A qualitative study of gender and work-life balance among men and women in mid-life. Gend Work Organ. 16(1), 151–172 (2009).

Waterhouse, P., Hill, A. Africa AHDS, 2017 undefined. Combining work and child care: The mothers’ experiences in Accra, Ghana. Taylor Francis. 2017;34(6):771–86.

Hunter, D., McCallum, J., Howes, D. Defining exploratory-descriptive qualitative (EDQ) research and considering its application to healthcare. J. Nurs. Health Care. 2019 May [cited 2024 Sep 28];4(1). Available from: http://dl6.globalstf.org/index.php/jnhc/article/view/1975.

Saunders, B. et al. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualisation and operationalisation. Qual Quant. 52(4), 1893–1907 (2018).

Forero, R. et al. Application of four-dimension criteria to assess the rigour of qualitative research in emergency medicine. BMC Health Serv Res. 18(1), 120 (2018).

Lincoln, Y. S. & Guba, E. G. But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Dir Program Eval. 1986(30), 73–84 (1986).

Denzin, N. K. The Landscape of Qualitative Research. SAGE; 2008. 633 p.

Creswell, J. W., Creswell, J. D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Sage Publications; 2017.

Maxwell, J. A. Qualitative research design: An Interactive Approach: An Interactive Approach. Sage; 2013 [cited 2024 Sep 28]. Available from: https://books.google.com/books?

Thorne, S. Data analysis in qualitative research. Evid Based Nurs. 3(3), 68–70 (2000).

Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., Terry, G. Thematic Analysis 48. 2019.

Lester, J. N., Cho, Y. & Lochmiller, C. R. Learning to do qualitative data analysis: A starting point. Hum Resour Dev Rev. 19(1), 94–106 (2020).

Hobfoll, S. E. Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Rev Gen Psychol. 6(4), 307–324 (2002).

Gomez, S., Khan, N., Malik, M. Journal MSOI, 2010 undefined. Empirically testing the relationship of social support, job satisfaction and work-family balance in Pakistani socio-cultural set-up. papers.ssrn.com.

Gold, J., Jia, L., Bentzley, J., … KB… J of G, 2021 undefined. WISE: A support group for graduate and post-graduate women in STEM. Taylor Francis.

Khanna, T., Patel, R., Akhtar, F. & Mehra, S. Relationship between partner support and psychological distress among young women during pregnancy: A mixed-method study from a low- and middle-income country. J Affect Disord Rep. 1(14), 100672 (2023).

Wayne, J. H., Michel, J. S. & Matthews, R. A. Balancing work and family: A theoretical explanation and longitudinal examination of its relation to spillover and role functioning. J Appl Psychol. 107(7), 1094–1114 (2022).

Dericks G, Thompson E, MRA& E, 2019 undefined. Determinants of PhD student satisfaction: The roles of supervisor, department, and peer qualities. Taylor Francis. 2019;44(7):1053–68.

Zhou, X., Zhong, J., Wang, J. & Zhang, L. How servant leadership influence employee spouses’ quality of family life: The social mindfulness lens. Curr Psychol. 43(32), 26326–26339 (2024).

Zhou, J. J., Zhang, Y., Ren, Q. Z., Li, T., Lin, G. D., Liao, M. Y., et al. Mediating effects of meaning in life on the relationship between family care, depression, and quality of life in Chinese older adults. Front Public Health. 2023 Apr 3 [cited 2024 Sep 28];11. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1079593/full

Liu, P., Wang, X., Li, A., Zhou, L. Predicting work-family balance: A new perspective on person-environment fit. Front Psychol. 2019 Aug 6 [cited 2024 Sep 28];10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01804/full

Boakye, A. O., Mensah, R. D., Bartrop-Sackey, M., Muah, P., Boakye, A. O. Striving to obtain a school-work-life balance: The full-time doctoral student. informingscience.com. 2021.

Demessie Bireda, A. Challenges to the doctoral journey: a case of female doctoral students from Ethiopia. Open Prax. 7(4):287–97.

Castro, V., Garcia, E. E., Cavazos Vela, J., Castro, A., Castro, V., Garcia, E. E., et al. The road to doctoral success and beyond. scholarworks.utrgv.edu. 2011.

Gold, J. A. et al. WISE: A support group for graduate and post-graduate women in STEM. Int J Group Psychother. 71(1), 81–115 (2021).

Monda, J. A. O. Finding a work-life balance: A study of the spiritual and social roles of pastors’ wives at the International Church of Christ, Nairobi. ShahidiHub Int J Theol Relig Stud. 3(1), 117–138 (2023).

Abubaker, M., Luobbad, M., Qasem, I. & Adam-Bagley, C. Work–life-balance policies for women and men in an islamic culture: A culture-centred and religious research perspective. Businesses. 2(3), 319–338 (2022).

Garti, A., Tzafrir, S. Work–family triangle synchronisation: Employee, manager, and spouse [internet]. De Gruyter; 2022 [cited 2024 Sep 28]. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110759808/html

Mason, A., Teaching JHI in E and, 2019 undefined. Students supporting students on the PhD journey: An evaluation of a mentoring scheme for international doctoral students. Taylor Francis. 2017;56(1):88–98.

Auger, D. Leisure in everyday life. Loisir Soc. 43(2), 127–128 (2020).

Mansfield, L., Daykin, N. Studies TKL, 2020 undefined. Leisure and well-being. Taylor Francis.

Lamanes, T. & Deacon, L. Supporting social sustainability in resource-based communities through leisure and recreation. Can Geogr. 63(1), 145–158 (2019).

Lamp, A., Cook, M., Smith, R. S., Sleep, G. B. 2019 undefined. Exercise, nutrition, sleep, and waking rest? academic.oup.com. 2019.

Araba, S., Lee, N., Saban, R. BMPIT, 2021 undefined. A Mediation Study on the Role of Coping Skills on the Relationships of Stress and Anxiety to the Quality of Sleep among Nursing Students. web1.aup.edu.ph.

Chirico, F., Sharma, M., Zaffina, S. & Magnavita, N. Spirituality and prayer on teacher stress and Burnout in an Italian Cohort: A pilot, before-after controlled study. Front Psychol. 21, 10 (2020).

McGuire, K. The Effects of Psychological and Physiological Stress and Cognitive Appraisal on Simulation Performance in Undergraduate Baccalaureate Nursing Students. 2019.

Jeynes, W. Education and Urban, 2020 U. A meta-analysis on the relationship between prayer and student outcomes. journals.sagepub.com. 2020;2020(8):1223–37.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the participants of the study for sharing their experiences with them.

Funding

No funding was received for the conduct of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization of the study, LA, CAP and M I Study design: JBPP, M, LA. Data collection: JBPP, C AP, MI and EM. Data analysis: M I, MA, A OY and SSO Manuscript writing: JBPP, M I, and EM. Manuscript Review: all authors read and approved the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study obtained ethical approval from the Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research (IRB 009/22–23). Participants gave verbal and written consent to participate in the study.

Consent for publication

All the participants gave consent for the study’s outcome to be published.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pwavra, J.B.P., Iddrisu, M., Poku, C.A. et al. A qualitative exploration of balancing family, work, and academics among female graduate nursing students in a lower-middle-income country. Sci Rep 15, 8216 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90724-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90724-7