Abstract

Moderate-scale farmland operations are pivotal for boosting agricultural productivity and sustainability. This study uses a moderated mediation model to explore the impact of formal financial credit, social capital, and crop diversity on these operations. Analyzing data from 985 farming households in Shandong Province, we discover that access to formal credit enhances the propensity for larger-scale farming by facilitating land resource inflow, with family farms mediating 38.59% of this effect. However, strong social capital and the cultivation of fruits and vegetables negatively modulate this mediation, indicating intricate dynamics that moderate the benefits of financial support. This research sheds light on the complex mechanisms of rural revitalization, emphasizing the interplay among financial resources, community dynamics, and agricultural choices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Will Rogers said, “Land is the only thing that endures.” As China deepens its economic reforms and opens up to the world, the traditional model of small-scale and fragmented farmland management no longer aligns with the coun-try’s rapid economic growth1. As a result, transferring land management rights, mobilizing rural production resources, and developing large-scale agricultural operations are now essential to China’s rural revitalization strategy. In this context, new agricultural business entities, such as family farms and farmers’ cooperatives, are pivotal for ensuring an orderly transition of farmland. Within this framework, new agricultural enterprises like family farms and farmers’ cooperatives play a key role in ensuring a smooth transition of farmland management2.

However, these new entities continue to encounter significant challenges, such as restricted access to finance and elevated borrowing costs. Research has shown that farmers’ financing options comprise formal credit from financial institutions and informal credit from social networks3. Significantly, credit products from institutions, endorsed by local governments, are vital for supporting agricultural production4,5.

Formal financial credit mainly supports farmers in self-employment, the purchase of production factors and social services, and the enhancement of productive capital6,7. As the transfer of farmland gains importance for agricultural growth, many studies have explored how formal financial credit affects the farmland market8,9. Interest is growing in how the characteristics of farmland management rights can ease farmers’ credit limitations10. Local governments have implemented preferential credit policies to boost entrepreneurship and targeted investments11, thereby enhancing the mobility of agricultural operators via farmland inflows. However, the existing literature does not comprehensively analyze the mechanisms and processes underlying these dynamics, nor does it sufficiently incorporate empirical testing based on survey data.

The level of formal credit support for agricultural operators indirectly indicates government policy backing11. With this support, farmers are more likely to start family farms and expand into large-scale agriculture12. Through scientific and intensive land management and industrial development, operators can enhance the construction and growth of the agricultural industry chain13. However, the literature currently lacks a thorough exploration of the relationship between formal financial credit and the development of family farms.

Recent studies have increasingly examined rural social networks and social capital, and their impact on acquiring formal agricultural credit and the orderly flow of agricultural inputs14,15. Research has shown that social relationships significantly shape land transaction formats and decrease lessors’ willingness and rental prices16. In addition to improving farmland transaction success rates, rural clan networks can significantly lower transaction costs17. Moreover, empirical data indicates that farmers embedded in family-based social networks are more inclined to adopt new fertilizers and seeds18.

Various studies have investigated how farmers’ social networks improve their access to formal credit19. The consensus is that these networks can boost the likelihood and limits of obtaining formal financial credit by reducing transaction costs20,21. The experience and education of strong network ties indirectly enhance the efficiency of entrepreneurial financing22. Social networks influence both external financing and the internal dynamics of information flow and structural transformation22.

As typical social units, rural communities effectively minimize transaction costs, notably in land inflow and rent negotiation, due to their advanced information handling capabilities23. Social network transactions can reduce moral hazards, as mutual trust among members facilitates the seamless execution of land transfer contracts23,24.

This paper suggests a positive correlation between the availability of rural formal financial credit and adequate land inflow for agricultural operators. However, gaps remain in understanding how these factors interrelate, especially the role of family farms in large-scale agriculture. It is necessary to analyze the mechanisms linking family farms, financial credit, and farmland transfer. Additionally, the impact of varied operating conditions and the diverse integration of rural social networks on the relationship between financial credit availability and large-scale land management needs exploration.

The structure of this paper is as follows: It begins by analyzing the link between formal financial credit and farmland inflow using transaction cost and selection behavior theories, proposing research hypotheses thereafter. The subsequent section introduces the data and descriptive statistics. Following sections detail the empirical specifications and present the results and discussions. The paper concludes with a summary of findings and policy implications.

Mechanism analysis and research hypotheses

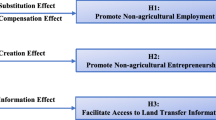

Transaction Cost Theory delineates three primary factors influencing transaction costs: predictability of transaction components, frequency of transactions, and risk management associated with specific assets25. For effective operation of moderately scaled agricultural lands, operators need both efficient resource allocation and significant support from local governmental bodies. External financing serves as a catalyst for agricultural operators, enabling the expansion of production capacities via strategic capital investments26. Enhanced credit access and reduced transaction costs act as incentives for farmers’ active participation in farmland market transactions, which leads to more efficient resource allocation. Drawing on this theoretical framework, the study proposes:

Hypothesis 1

Enhanced access to formal credit significantly promotes farmland inflow, thereby bolstering the scalability of agricultural operations by facilitating more efficient utilization of land resources.

The Theory of Planned Behavior asserts a direct linkage between strategic planning and behavior execution, mediated by the alignment of perceived behavioral control with intentions27. Furthermore, the theory posits that as Perceived Behavioral Control increases, behaviors are more likely to manifest, provided that intentions remain constant28,29. In the agricultural sector, the establishment of family farms is considered crucial for attaining moderate-scale development, particularly in light of substantial policy support from various governmental level30.

Hypothesis 2

Family farms act as intermediaries in facilitating farmers’ access to formal financial credit, thereby boosting farmland inflow and aiding agricultural expansion.

If substantiated, the critical role of family farms as intermediaries in linking formal financial credit with moderate-scale production suggests that external factors impacting these farms indirectly modify their mediation capabilities. The Theory of Planned Behavior maintains that the decision to establish family farms is based on assessing the advantages over fragmented farming31. Operators possessing significant social capital can discern the advantages and drawbacks of family farms and their optimal size through their network ties, leveraging both bonding and bridging forms of social capital, which differently affect their access to resources and information32,33,34,35.

Moreover, the ambition of agricultural operators to upscale their operations via family farms hinges critically on their income generation strategies and their level of integration into local and regional markets, influenced by their social capital.

Therefore, the study proposes those hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3

Variations in social capital and selected crop types modulate the influence of formal financial credit on land management expansion, with family farms serving as pivotal intermediaries.

While social capital is typically viewed as a resource that facilitates access to various forms of support, including credit, in the agricultural sector it can sometimes act as a barrier to formal financial services36,37. This paradox arises because the strong reliance on informal networks within rural communities might limit exposure to and interest in formal financial products. Farmers deeply embedded in traditional social structures may find it difficult to meet the stringent requirements or lack awareness of formal credit opportunities38.

Hypothesis 3.1

Social capital negatively influences farmers’ ability to obtain formal financial credit for land acquisition.

The type of crops a farmer chooses to cultivate can significantly influence their ability to secure formal financial credit38. Lenders often perceive crops such as vegetables and fruits as high-risk due to their perishability and market volatility, which can lead to hesitancy in providing loans for these types of agriculture. Conversely, grain crops are generally seen as lower risk because of their longer shelf life and more stable market demand39. This perception affects the willingness of financial institutions to extend credit40.

Hypothesis 3.2

Choosing vegetable and fruit crops negatively impacts farmers’ access to formal financial credit for land inflow, while grain crops have a positive effect.

Further analysis of the nuances within Hypothesis 3 could offer clarity on how specific types of social capital and crop choices either facilitate or hinder access to credit and land management practices.

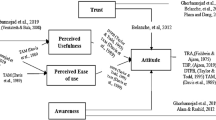

Based on the theoretical discussion, The proposed analytical framework, illustrated in Fig. 1, delineates the intermediary roles played by various factors in linking formal financial credit to farmland inflow. However, empirical testing is necessary to validate these hypotheses and assess the research path’s feasibility.

Data and descriptive statistics

Data

Data were collected from a field survey conducted in January 2022 across nine districts in Yantai, Zibo, and Zaozhuang—cities within Shandong Province—focusing on agricultural socialization services and planting efficiency. Shandong Province is a major agricultural hub in China, leading in both vegetable and fruit production and as a key grain-producing region for wheat and maize. Its distinct regional characteristics reflect broader agricultural patterns in other developing countries. Yantai, an economically developed coastal city in the east, specializes in horticultural crops such as vegetables and fruits. Zibo, centrally located, has an average economic status and produces both grains and horticultural crops, indicative of a transitional economy. Zaozhuang, situated in the west, is less economically developed and focuses mainly on grain production. This regional diversity enables a comprehensive analysis of varied agricultural practices within a single province.

By leveraging the diverse regional and industrial characteristics of Shandong Province, the study enhances the generalizability of its findings and provides valuable insights for agricultural development and land reform in other developing countries. Comparing these results with similar studies from different regions or countries further contextualizes the findings, distinguishing between universal trends and location-specific factors.

Using stratified sampling, 1,350 questionnaires were distributed to local growers, resulting in 985 valid responses and an effective response rate of 72.96%. The questionnaire was specifically designed for this study and does not involve any copyrighted scales. Detailed data are presented in Table 1.

Variable explanation and descriptive statistics

Dependent variable

The dependent variable for this study is the scale of land leased by the interviewed grower households in 2021. Additionally, land inflow for these households in the same year is analyzed as a binary variable to test robustness.

Independent variable

The independent variable is the availability of formal financial credit, measured by whether households have obtained credit from institutions such as commercial banks, credit cooperatives, and rural banks. Research indicates a strong positive correlation between this availability, farmers’ borrowing intentions, actual needs, farmland area, and business goals, influencing both farmers’ decisions and lenders’ practices41. As agricultural industrialization progresses, operational loans have surpassed consumer loans in formal credit loans for farmers, with the proportion of business loans aimed at expanding production scale gradually increasing42.

Mediation variable

Family farm establishment is a mediation variable. It connects large-scale land operations with enhanced credit availability. Family farms are prioritized in modern Chinese agriculture due to their stable financial structure and market recognition, facilitating access to external financing and credit. These entities not only help distribute land resources efficiently but also improve operational scalability and profitability, underpinned by government policies that encourage agricultural consolidation and modernization.

Moderation variables

Farmers with rich social capital can access more information due to their endowment resources, effectively reducing the cost of searching for land resources and information acquisition43,44,45. Additionally, transactions within social network relationships facilitate land transactions due to mutual trust46. This study uses the presence of direct or collateral relatives holding leadership positions in villages, towns, or other government departments to represent social capital47, and uses it as a moderating variable. Furthermore, the main agricultural production item of the farm household, particularly whether it is vegetable and fruit planting, is used as another moderating variable.

Control variables

Control variables include the age and education level of the household head, total household income, and village endowment, as indicated by relevant literature. Additional details on these variables are provided in Table 2.

Empirical specifications

Mediation effect test

Y: The dependent variable representing farmland inflow, measuring the extent to which farmers acquire additional land.

X: The primary independent variable indicating access to formal financial credit, quantified by the availability or amount of formal loans received by farmers.

Controls: A set of control variables such as age, education level, farm size, and other socio-economic factors that might influence farmland inflow.

e1: The error term capturing unobserved factors affecting Y, assumed to be independently and identically distributed.

\(\varvec{F}({\varvec{M}}_{\varvec{i}})\): The logistic function transforming the mediation variable \({\varvec{M}}_{\varvec{i}}\) into a probability, used in logistic regression.

\({\varvec{M}}_{\varvec{i}}\): Mediation variable representing the establishment of family farms by farmer , typically a binary variable (1 if established, 0 otherwise).

\({\varvec{x}}_{\varvec{i}}\): Independent variable for farmer i, corresponding to X but specific to individual observations.

\({\varvec{e}}_{\mathbf{2}}\): Error term capturing unobserved factors affecting \({\varvec{M}}_{\varvec{i}}\), assumed to follow a logistic distribution.

\({\varvec{e}}_{\mathbf{3}}\): Error term capturing unobserved factors affecting Y in the mediation model.

The mediation model is configured with a categorical mediating variable. Logit regression is used instead of linear regression to handle the categorical nature of the mediator48. For models with a continuous dependent variable (Eqs. 1 and 3), linear regression is applied. In Eq. 2, logit regression addresses the scale inconsistency and reduces bias in the estimates of the mediation effect49.

A classical stepwise regression approach is employed to assess the mediation effect50. The process involves two steps:

-

1.

Assessing the impact of formal financial credit availability on the establishment of family farms (Eq. 2). A significant coefficient ‘a’ suggests a relationship but does not confirm a mediation effect, necessitating further analysis.

-

2.

Evaluating the combined influence of credit availability and family farm establishment on farmland inflow (Eq. 3).

Moderated mediation test

The study examines a moderated mediation model where the relationship between formal financial credit availability and land transfer in family farms is influenced by social capital and crop type diversity. This approach uses social capital quantity and the specific agricultural sector (vegetable and fruit versus others) as moderators51,52.

In these equations, m represents the observed mediator variable, indicating whether the farmer has established a family farm (coded as 1 if yes, 0 if no). Social capital and the cultivation of vegetables and fruits are defined as the moderating variable w. The scale of land leasing is defined as the dependent variable Y. The term x*w represents the interaction between the independent variable x and the moderating variable w.

Results and discussion

Empirical results

Table 3 displays the mediation effect regression results for family farms. The logit model reports significant average marginal effect coefficients: c = 0.57, b = 2.59, a = 0.30, and c’=0.35, confirming the significance of the mediation effect. The mediation effect was decomposed using the KHB method, appropriate for the non-linear regression of Model 2. The direct effect of formal financial credit on land inflow is 0.35, with an indirect effect through family farm establishment of 0.22, constituting 38.59% of the total effect, confirming the significant mediation effect. The Bootstrap method confirmed a mediation effect of 0.21 with confidence intervals of LLCI = 0.15 and ULCI = 0.26, not including 0, thus indicating significant and robust mediation and direct effects of family farms.

The average marginal effect of the mediation variable on the independent variable logit regression is reported in Model 4. Model 5 is the linear regression of the dependent variable on the mediator variable and independent variable. The moderation variable in Model 4a and Model 5a is social capital, and in Model 4b and Model 5b is variable of cash crops. All above variables are centralized.

Analysis of the interaction coefficients in Models 4 and 5 reveals a significant negative effect, supporting Hypothesis 3.1: high social capital negatively impacts the use of formal financial credit for setting up family farms and transferring land. At the same time, the focus on marketization in the cultivation of vegetables and fruits also makes the industry characteristics negatively adjust the mediation effect of the availability of formal financial credit on the inflow of farmland through the establishment of family farms.

The bias-corrected Bootstrap analysis reveals significant moderation effects: low social capital (β=+0.051) and high social capital (β=− 0.012) suggest a decreasing negative impact with increased social capital, supporting Hypothesis 3.1. For crop types, the effect is negative for vegetable and fruit (β=-0.003) and positive for non-vegetable and fruit crops (β = 0.014), validating Hypothesis 3.2 on cropping selection heterogeneity. For specific data, see Table 5.

In Table 5, The moderation effect (vegetable and fruit farming) is not significant (β=− 0.003, 95% confidence interval [− 0.009, − 0.001], excluding 0), moderation effect (non-vegetable and fruit farming) is statistical significant (β = 0.014, 95% confidence interval) [0.008, 0.037], excluding 0). This indicates that the moderation effect of cropping selection heterogeneity is established (negative for vegetable and fruit cropping, and positive for non-vegetable and fruit cropping). Hypothesis 3.2 is held.

Robustness test

For the robustness test, the land lease scale of farmers in 2019 was recategorized: no inflow (≤ 0 acres) = 0, and inflow (> 0 acres) = 1. Table 4, Model 6 reports the marginal effects with social capital as the moderator in Model 6a and the vegetable and fruit industry in Model 6b. The results indicate that both social capital and the planting of vegetables and fruits negatively moderated the mediation effect, supporting Hypothesis 3.Taking the regression coefficients of Model 5a and Model 5b as examples, we draw the adjustment effect diagram (see Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2 for details).

Using regression coefficients from Model 5a and Model 5b, adjustment effect diagrams were constructed (refer to Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). The diagrams confirm that increased social capital and the choice of vegetable and fruit crops negatively regulate the effect of formal financial credit on farmland inflow. Conversely, staple crops have a positive regulatory effect, thereby validating Hypothesis 3.2.

Discussion

The mediation and moderated mediation models robustly illustrate the pivotal role of family farms in bridging the relationship between farmers’ access to formal credit and the expansion of farmland management, evidenced by a mediating effect value of 0.21. Intriguingly, both social capital and the selection of specific farming types—namely vegetable and fruit cultivation—exert a negative moderating influence on this mediation. This indicates that elevated levels of social capital and particular crop choices can attenuate the beneficial mediation effect of family farms on land management expansion.

These outcomes resonate with extant literature that underscores the intricate nature of social capital within agricultural development. Kobeissi posits that while social capital can catalyze collective action, it may simultaneously entrench prevailing norms that stifle innovation and limit access to formal financial services53. Complementarily, other studies have identified that in certain contexts, robust bonding social capital can restrict individuals’ access to external resources, including formal credit avenues54,55.

Contrary to research that highlights the positive ramifications of social networks on credit access56,20, our findings reveal a negative moderation effect of social capital. This divergence may stem from the dominant form of social capital among the surveyed farmers. Specifically, bonding social capital, characterized by tight-knit group affiliations, might disincentivize reliance on formal financial institutions, fostering a preference for traditional, informal lending mechanisms57.

Furthermore, the association between crop choice and credit access unveils that cultivating vegetables and fruits adversely affects the availability of formal financial credit. This aligns with Kumar’s observations, which indicate that high-value yet riskier crops encounter more significant financing hurdles due to their vulnerability to market volatility and perishability58. In contrast, grain crops are generally perceived as lower risk by financial institutions, thereby facilitating more straightforward credit access59.

The study’s methodological approach, employing a moderated mediation model, represents a sophisticated analytical strategy that adeptly captures the multifaceted interactions between formal financial credit availability, social capital, and crop type heterogeneity in influencing farmland operations’ scale. This nuanced model not only elucidates the conditions under which family farms mediate credit-land management relationships but also highlights the complex interplay of social and agronomic factors that can either enhance or impede agricultural expansion. Such insights are invaluable for policymakers and financial institutions aiming to refine credit systems and promote sustainable agricultural growth, particularly in regions with analogous socio-economic landscapes. By revealing the conditional dynamics that govern credit utilization through family farms, this research contributes significantly to the broader discourse in agricultural economics and offers pragmatic pathways for fostering resilient and scalable farming practices.

Conclusion and policy implications

This study leverages survey data from farming households in Shandong Province, China, employing a moderated mediation analysis to elucidate the intricate interplay between formal financial credit availability, family farms, social capital, and crop type heterogeneity in shaping moderately large-scale farmland management. The empirical findings reveal three pivotal insights:

-

1.

The availability of formal financial credit positively promotes the willingness of farmers to expand the scale of operation, encouraging operators to expand the scale of planting through land inflow.

-

2.

The establishment of family farms depends on farmers’ ability to obtain formal financial credit. There is a partial mediation effect in the process of supporting land inflow.

-

3.

Social capital and the choice of vegetable and fruit planting have a negative moderation effect in the mediation process of family farms’ financial credit affecting the inflow of agricultural land.

Based on these findings, this study proposes the following policy recommendations:

-

1.

Global Expansion of Formal Financial Credit Access. International development agencies and national governments should endeavor to broaden access to formal financial credit for farmers. This entails designing bespoke financial products tailored to address the unique challenges inherent in rural farming across diverse underdeveloped and developing regions.

-

2.

Enhancement of Targeted Social Services. It is imperative to implement specialized social service programs that bolster agricultural support systems within rural communities. By improving market access, management skills, and infrastructural support, these programs can empower farmers, particularly in areas lacking robust agricultural support frameworks.

-

3.

International Investment in Agricultural Training. Promoting global investment in agricultural education and training initiatives is essential. These programs should integrate traditional agricultural knowledge with modern technological advancements, emphasizing sustainability and efficiency to support family-owned farms in vulnerable regions.

-

4.

Support for Sustainable Grain Production: Policymakers should foster sustainable grain production through supportive policies and innovative farming techniques. Encouraging practices that reduce reliance on government subsidies and enhance self-sufficiency will contribute to resilient agricultural systems across various landscapes.

While the study offers valuable insights, its geographic focus on Shandong Province may constrain the generalizability of the findings. Future research should incorporate multi-region panel data to enhance comparability and external validity, acknowledging the regional diversity emphasized in prior agricultural studies. Additionally, the methodological approach could be fortified by employing structural equation modeling for latent variable analysis, which would provide a more profound understanding of the underlying constructs and causal relationships. Addressing these limitations will not only bolster the robustness of subsequent studies but also refine the policy recommendations to be more universally applicable.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed in this study are the result of research conducted by the Yi-Feng Zhang research team, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Li, X., Guo, H., Jin, S., Ma, W. & Zeng, Y. Do farmers gain internet dividends from E-commerce adoption? Evidence from China. Food Policy. 101, 102024 (2021).

Xu, H. & Ye, J. Soil as a site of struggle: differentiated rifts under different modes of Farming in Intensive Commercial Agriculture in Urbanizing China. J. Peasant Stud. 49, 1207–1228 (2022).

Tian, X., Wu, M., Ma, L. & Wang, N. Rural finance, scale management and rural industrial integration. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2, 349–365 (2020).

Yep, R., Fong, C. L. & Conflicts Rural Finance and capacity of the Chinese state. Public. Adm. Dev. 29, 69–78 (2009).

Zhou, J., Fan, X., Li, C. & Shang, G. Factors influencing the coupling of the development of rural urbanization and rural Finance: Evidence from Rural China. Land 11, 853 (2022).

Kiros, S. & Meshesha, G. B. Factors affecting farmers’ access to formal financial credit in Basona Worana District, North Showa Zone, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia. Cogent Econ. Finance. 10, 2035043 (2022).

Benami, E. & Carter, M. R. Can digital technologies reshape rural microfinance? Implications for savings, credit. Insurance Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy. 43, 1196–1220 (2021).

Asah, F. T., Louw, L. & Williams, J. The availability of credit from the formal financial sector to small and medium enterprises in South Africa. J. Econ. Financ. Sci. 13, 10 (2020).

Dzadze, P., Osei, M. J., Aidoo, R. & Nurah, G. K. Factors determining access to formal credit in Ghana: A case study of smallholder farmers in the Abura-Asebu Kwamankese District of Central Region of Ghana. J. Dev. Agric. Econ. 4, 416–423 (2012).

Domeher, D. & Abdulai, R. Access to credit in the developing world: Does land registration matter? Third World Q. 33, 161–175 (2012).

Li, X. & Huo, X. Impacts of Land Market policies on formal credit accessibility and agricultural net income: Evidence from China’s apple growers. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 173, 121132 (2021).

Li, C., Ma, W., Mishra, A. K. & Gao, L. Access to credit and farmland rental market participation: Evidence from rural China. China Econ. Rev. 63, 101523 (2020).

Bergquist, L. F. & Dinerstein, M. Competition and entry in agricultural markets: Experimental evidence from Kenya. Am. Econ. Rev. 110, 3705–3747 (2020).

Deininger, K. Challenges posed by the new wave of farmland investment. J. Peasant Stud. 38, 217–247 (2011).

Li, Z. Rural Finance, Rural finance, farmland transfer and agricultural production technical efficiency: Evidence from China. In 2010 2nd IEEE International Conference on Information and Financial Engineering, 364–368 (2010).

Robison, L. J., Myers, R. J. & Siles, M. E. Social capital and the terms of trade for farmland Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy. 24, 44–58 (2002).

Zhang, H., Luo, J., Cheng, M. & Duan, P. How does rural household differentiation affect the availability of farmland management right mortgages in China? Emerg. Mark. Financ Trade. 56, 2509–2528 (2020).

Isham, J. The effect of social capital on fertiliser adoption: Evidence from rural Tanzania. J. Afr. Econ. 11, 39–60 (2002).

Wydick, B., Hayes, H. K. & Kempf, S. H. Social networks, neighborhood effects, and credit access: evidence from rural Guatemala. World Dev. 39, 974–982 (2011).

Banerjee, A. et al. Changes in social network structure in response to exposure to formal credit markets. Rev. Econ. Stud. 91, 1331–1372 (2024).

Okten, C. & Osili, U. O. Social networks and credit access in Indonesia. World Dev. 32, 1225–1246 (2004).

Dufhues, T., Buchenrieder, G. & Munkung, N. Social capital and market imperfections: Accessing formal credit in Thailand. Oxf. Dev. Stud. 41, 54–75 (2013).

Yuan, Y. & Xu, L. Are poor able to access the informal credit market? Evidence from rural households in China. China Econ. Rev. 33, 232–246 (2015).

Turvey, C. G. & Kong, R. Informal lending amongst friends and relatives: can microcredit compete in rural China? China Econ. Rev. 21, 544–556 (2010).

Williamson, O. E. The economics of organization: The transaction cost approach. Am. J. Sociol. 87, 548–577 (1981).

Sule, A. & Yusuf, A. External financing and agricultural productivity in Nigeria. J. Econ. Financ. 3, 307–320 (2019).

Conner, M. & Armitage, C. J. Extending the theory of planned behavior: A review and avenues for further research. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 28, 1429–1464 (1998).

Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 50, 179–211 (1991).

Castellacci, F. Co-evolutionary growth: A system dynamics model. Econ. Model. 70, 272–287 (2018).

Yang, M. & Gao, J. The impact of government support on family farm—A chain mediation model: Empirical evidence from China. J. Asian Finance Econ. Bus. 9, 325–332 (2022).

Suess-Reyes, J. & Fuetsch, E. The future of family farming: A literature review on innovative, sustainable and succession-oriented strategies. J. Rural Stud. 47, 117–140 (2016).

Barrett, C. B. et al. Smallholder participation in contract farming: Comparative evidence from five countries. World Dev. 40, 715–730 (2012).

Narayan, D. & Pritchett, L. Cents and sociability: Household Income and Social Capital in Rural Tanzania. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change. 47, 871–897 (1999).

Zhu, Q., Krikke, H. & Caniëls, M. C. Supply Chain Integration: Value Creation through Managing Inter-Organizational Learning. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manage. 38, 211–229 (2018).

Ceci, F., Masciarelli, F. & Poledrini, S. How social capital affects innovation in a cultural network: Exploring the role of bonding and bridging social capital. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 23, 895–918 (2020).

Anderson, C. L., Locker, L., Nugent, R. & Microcredit social capital, and common pool resources. World Dev. 30, 95–105 (2002).

Pretty, J. & Ward, H. Social capital and the environment. World Dev. 29, 209–227 (2001).

Taylor, M., Bhasme, S. M. & Farmers Extension networks and the politics of agricultural knowledge transfer. J. Rural Stud. 64, 1–10 (2018).

Stathers, T., Lamboll, R. & Mvumi, B. M. Postharvest agriculture in changing climates: Its importance to African smallholder farmers. Food Secur. 5, 361–392 (2013).

Katsaiti, M. & Khraiche, M. Does access to credit alter migration intentions? Empir. Econ. 65, 1823–1854 (2023).

Wu, Y., Luo, J., Zhang, X. & Skitmore, M. Urban growth dilemmas and solutions in China: Looking forward to 2030. Habitat Int. 56, 42–51 (2016).

Qian, C. et al. Effect of personality traits on smallholders’ land renting behavior: Theory and evidence from the North China Plain. China Econ. Rev. 62, 101510 (2020).

Alston, J. M. Reflections on agricultural R&D, productivity, and the data constraint: Unfinished business, unsettled issues. Am. J. Agr Econ. 0, 1–22 (2017).

Knack, S. & Keefer, P. Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. Q. J. Econ. 112, 1251–1288 (1997).

Escandon-Barbosa, D., Urbano-Pulido, D. & Hurtado-Ayala, A. Exploring the relationship between formal and informal institutions, social capital, and entrepreneurial activity in developing and developed countries. Sustainability 11, 550 (2019).

Huy, H. T., Lyne, M., Ratna, N. & Nuthall, P. Drivers of transaction costs affecting participation in the rental market for Cropland in Vietnam. Aust J. Agric Resour. Econ. 60, 476–492 (2016).

Li, X., Guo, H., Jin, S., Ma, W.& Zeng, Y. Do farmers gain internet dividends from E-commerce adoption? Evidence from China. Food Policy. 101, 102024 (2021).

Wen, Z. & Ye, B. Analyses of mediating effects: The development of methods and models. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 22, 731 (2014).

MacKinnon, D. P. & Fairchild, A. J. Current directions in mediation analysis. Curr. Dir. Psychol. 18, 16–20 (2009).

Muller, D., Judd, C. M. & Yzerbyt, V. Y. When Moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 89, 852–863 (2005).

Baron, R. M. & Kenny, D. A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51, 1173 (1986).

Breen, R., Karlson, K. B., & Holm, A. Total, direct, and indirect effects in logit and probit models. Sociol. Methods Res. 42, 164–191 (2013).

Kobeissi, N., Hasan, I., Wang, B., Wang, H. & Yin, D. Social capital and regional innovation: Evidence from private firms in the US. Reg. Stud. 57, 57–71 (2023).

Craig, A., Hutton, C., Musa, F. B., Sheffield, J. & Bonding, bridging and linking social capital combinations for food access: A gendered case study exploring temporal differences in Southern Malawi. J. Rural Stud. 101, 103039 (2023).

Yang, Y., Huang, Y., Huang, J. & Nie, F. The role of social capital in the impact of multiple shocks on households’ coping strategies in underdeveloped rural areas. Sci. Rep. 14, 14218 (2024).

Blumenstock, J. E., Chi, G. & Tan, X. Migration and the value of social networks. Rev. Econ. Stud. rdad113 (2023).

Wu, A., Neilson, J. & Connell, J. Remittances and social capital: Livelihood strategies of timorese workers participating in the Australian seasonal worker programme. Third World Q. 44, 96–114 (2023).

Kumar, A. & Agrawal, S. Challenges and opportunities for agri-fresh food supply chain management in India. Comput. Electron. Agric. 212, 108161 (2023).

Jindo, K., Andersson, J. A., Quist-Wessel, F., Onyango, J. & Langeveld, J. W. Gendered investment differences among Smallholder farmers: Evidence from a Microcredit Programme in Western Kenya. Food Secur. 15, 1489–1504 (2023).

Funding

Supported by 2023 Jiangsu Universities' Major Project for Philosophy and Social Sciences Research (2023SJZD064), Project Grantee: Dr. Zhang Yifeng; Supported by 2024 Jiangsu Provincial University Social Science Federation Development Special Project (24GSB-003), Project Grantee: Dr. Zhang Yifeng.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wei Dengfeng developed the primary conceptual framework and drafted the initial manuscript. Dr. Yifeng Zhang was responsible for conducting the empirical analysis and crafting the final version of the manuscript. Both authors collaboratively revised and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, DF., Zhang, YF. Impact of formal credit and social capital on the scalability of agricultural operations. Sci Rep 15, 6603 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90758-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90758-x