Abstract

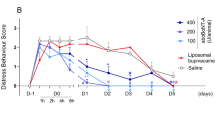

Previously, abobotulinumtoxinA (aboBoNT-A) injected intraoperatively resulted in effective, but delayed post-surgical analgesia in pigs. Here, we explore the efficacy of preemptively administered aboBoNT-A in intact animals on pain and associated behaviors following a full-skin-muscle incision and retraction surgery on the lower back. AboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) or saline, distributed across ten points, were injected around anticipated incision 15, 5, or 1 day before surgery via ID route (part A) or 15 days before surgery via ID, intramuscular (IM) or subcutaneous (SC) routes (part B). We assessed mechanical sensitivity (withdrawal force; WF), distress behavior score (DBS), and latency to approach the investigator before and after surgery for 7 days.AboBoNT-A, injected ID 15 days before surgery, didn’t alter any baseline behaviors, but resulted in 5-fold increases in WF, 75% reduction in DBS and 70% reduction in approach latencies (all p < 0.01). Injections 5 days before surgery led to similar effects, albeit with a fewer animals reaching thresholds, while those made 1 day before surgery were less effective. SC and IM injections were ineffective. Thus, aboBoNT-A administered ID 15 days before surgery represents the most optimal condition for postoperative analgesia. These findings warrant for clinical investigation of preemptively administered aboBoNT-A in postsurgical pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There are over 313 million surgical procedures undertaken annually worldwide. Pain, an unavoidable consequence of surgery, is thought to be severe in 20 to 40% of these patients1. Severe post-surgical pain is linked to patients’ suffering, immobility, delayed recovery, prolonged hospital stay and increased risks of pain chronicity2,3. Opioid drugs are the most commonly used for management of severe post-surgical pain, despite associated acute side-effects, slower healing and risk of addiction4. Thus, there is a need for novel, non-opioid, analgesic drugs that are well-tolerated and provide effective, prolonged relief from pain after surgery.

Botulinum neurotoxins (BoNTs) belong to a diverse group of proteins produced in nature by Gram-positive, anaerobic bacteria of the genus Clostridium5. BoNTs are classified into seven serotypes (A through G) and over 40 subtypes based on distinct amino acid sequence and immunological properties6. Recently several novel serotypes, including BoNT-H and BoNT-X, have been discovered7. Despite their diversity, BoNTs share molecular structure, as all serotypes are produced as an inactive, single-chain polypeptide of 150 kDa, which is subsequently cleaved into a pharmacologically active form consisting of a heavy chain (100 kDa) and a light chain (50 kDa) connected by a disulfide bond6. BoNTs are known for their neurospecific activity, as they cleave soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive-factor attachment receptor (SNARE) proteins. SNARE proteins, including synaptosomal-associated protein 25 (SNAP25), vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP, also known as synaptobrevin) and syntaxins 1 A/1B, are a family of proteins essential for the fusion of synaptic vesicles with the presynaptic plasma membrane8. BoNT-mediated proteolysis of SNARE proteins in motor neurons at the neuromuscular junction results in the interruption of acetylcholine neurotransmission leading to flaccid paralysis observed in botulism6. At the same time, neurospecific activity, limited diffusion from the injected site and remarkably long duration of action, lasting several months, made BoNT an effective and safe drug in aesthetic dermatology and a range of medical conditions characterized by muscle and glandular hyperactivity9.

There is a converging in vitro, in vivo, and clinical evidence that BoNTs can also act along the nociceptive pathway in the peripheral and central nervous systems and alleviate several types of pain10,11,12. For example, in vitro, BoNT-A applied to the cultured neurons, inhibits the release of glutamate, calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and other pain-related neurotransmitters from sensory neurons in the dorsal root ganglia and trigeminal ganglia as well as trigeminal satellite cultured cells13,14,15,16. In vivo, in models of pain in animals, analgesic activity of BoNT is characterized by delayed onset and prolonged duration of action. For example, BoNT-A injected subcutaneously (SC) in the plantar surface of the rat 2 h before formalin injection in the same area, failed to reduce pain-related behaviors (lifting and licking), whereas injections made 5 h to 12 days before formalin administration resulted in significant reduction of these behaviors, indicative of analgesic activity17. Analgesic efficacy of peripherally-administered BoNT appears to be linked to its transport into the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) and the spinal cord10,18,19. BoNT-B injected unilaterally into the hind paw in mice reduced formalin-induced pain-related behaviors, ipsilateral DRG SNARE proteins, formalin-induced neuronal activation in the dorsal horn neurons of the spinal cord and formalin—evoked dorsal horn substance P release18. In the clinic, chronic migraine treatment remains the only pain-related indication approved for the use of BoNT20,21. Furthermore, based on the outcome of multiple clinical trials, level A evidence for analgesic efficacy of BoNT exists in postherpetic neuralgia, posttraumatic neuralgia and trigeminal neuralgia, while level B evidence, suggesting probable efficacy, exists in diabetic neuropathy, plantar fasciitis, piriformis syndrome, chronic low back pain and several other pain conditions22.

Despite approval for migraine, BoNT’s broader development and clinical use as an effective analgesic drug remains slow, largely led by its off-label uses. Paucity of translational studies that can offer guidance to clinicians, is likely to be one of the reasons that hinder the progress of BoNT in the field of pain. There is scarcity of experimental studies that explore systematically the experimental conditions required for optimal analgesic efficacy of BoNT. The experimental variables that need to be investigated systematically in a translational model before being transferable to a clinical trial, include selection of the doses for a given BoNT-A product, sites of injection and their number for each condition, routes of administration, timing of the injection and others.

Recently, we reported that abobotulinumtoxinA (aboBoNT-A), administered intraoperatively (i.e. immediately at the end of surgery) at 100–400 U/animal, distributed across ten injection points (10–40 U/point) around the 7 cm-long surgical incision using ID route delivered a broad analgesic activity in a translational model of post-surgical pain in juvenile pigs23. Specifically, aboBoNT-A reversed mechanical allodynia, reduced pain-related distress and normalized approaching behavior following a full-skin-muscle incision and retraction (SMIR) surgery on the lower back of juvenile pigs. A noticeable feature of analgesic activity of aboBoNT-A in the model was its delayed onset following the injection. Specifically, analgesic activity, largely absent up to 6 h following surgery, emerged 24 to 48 h post-injection as a mild, but statistically significant increase in withdrawal force, while reaching its maximal magnitude across readouts 4–5 days post-injection23. Based on these data we hypothesized that administration of aboBoNT-A around anticipated incision in intact animals preemptively, before surgery, would effectively advance the onset of its analgesic activity and align it with the onset of post-surgical pain on Day 0. To test this hypothesis and to identify the most optimal pretreatment period, aboBoNT-A or saline were injected around anticipated incision in naïve, intact animals either 15, 5, or 1 day before surgery using ID route (phase A). Selection of pretreatment days 15, 5, and 1 for preemptive treatment was directly linked to the outcome of our previous study involving intraoperatively administered aboBoNT-A23. Specifically, we noticed that on Day 5, the last day of the study, the majority of aboBoNT-A-treated animals showed maximal inhibition of post-surgical pain, while a small group continued exhibiting sub-maximal effects of treatment23. Based on these results we hypothesized that preemptive treatment of intact animals 5 days before the surgery, would advance the onset of aboBoNT-A’s analgesic efficacy and ensure the expression of marked analgesic activity for the majority of animals at the onset of post-surgical pain on Day 0. Fifteen day pretreatment time was selected in order to investigate whether markedly longer pretreatment period would deliver maximal analgesic effects in all treated animals. With one day pretreatment time, on the other hand, we tested a hypothesis that this pretreatment period was largely insufficient for the effective analgesic activity of aboBoNT-A immediately after surgery.

In phase B, aboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) was delivered around anticipated incision preemptively, 15 days before surgery using ID, intramuscular (IM) or subcutaneous (SC) routes to identify the most optimal route of administration. Animals were assessed for mechanical sensitivity, pain-related distress, latencies to approach the investigator and open-field activity, as done in our previous study23. The measurements were made at multiple timepoints before and after treatment with aboBoNT-A/saline as well as after surgery for 7 consecutive days.

Results

Part A

Treatment 15 days before surgery

Von Frey test

At baseline, sixteen days before surgery (Day − 16), all intact animals exhibited normal mechanical sensitivity, as they responded to the withdrawal force (WF) of 60 g (Fig. 1A). AboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) or saline, injected on Day − 15 via ID route, had no effect on mechanical sensitivity before surgery when animals were tested on Days − 13, -10, -4 and − 1 (Fig. 1A). One hour following surgery on Day 0, however, saline-treated controls responded to the WF of 2 g, indicative of mechanical hypersensitivity (i.e. allodynia; Fig. 1A). The WF responses of saline-treated controls remained stable thereafter with only slow and minimal recovery to 5 g by Day 7 (Fig. 1A). The WF responses of animals treated preemptively with aboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) on Day − 15 were markedly and significantly higher than those in saline-treated controls for the entire post-operative period (Fig. 1A). Specifically, 1 h following surgery, the WF of aboBoNT-A-treated animals was approximately 10 g, 5-fold higher (p < 0.01) than that in saline-treated controls, while reaching 26 g (p < 0.01) 6 h following surgery (Fig. 1A). The WF responses of aboBoNT-A-treated animals remained between 15 g and 26 g (p < 0.01) on Days 1–4, while increasing beyond 26 g on Days 5–7 (Fig. 1A).

Effects of aboBoNT-A and saline administered 15 days before surgery on postsurgical pain-related behavioral responses in juvenile pigs. Animals received ID administration of aboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) or vehicle (saline) preemptively, 15 days before surgery (Day-15; blue arrows; n=6/group). Assessment of mechanical sensitivity/withdrawal force (WF; g, A, B), DBS (C, D) and latency to approach (sec; E, F) was done at multiple time-points before and after a full-skin-muscle incision and retraction surgery (red arrows). The green dotted line at 26 g on panel A represents the mechanical sensitivity threshold between normal mechanical sensitivity and mechanical hypersensitivity/allodynia. Each point on panels A, C, E represents the observed mean (+ SEM). Panel B shows the proportion of animals with normal mechanical sensitivity (WF ≥ 26 g) vs. hypersensitivity/allodynia (WF < 26 g). Panel D shows the proportion of animals exhibiting moderate to high distress (DBS ≥ 2) vs. those with minimal or no distress (DBS < 2). Panel F shows the proportion of animals that initiated approach in ≤40 s or those that took more than 40 s in the Approaching test. *p<0.01 vs. saline-injected animals. AboBoNT-A, abobotulinumtoxinA; ID, intradermal; DBS, distress behavior score; U, unit; WF, withdrawal force.

The proportion of animals with normal mechanical sensitivity (i.e. WF ≥ 26 g) in each group also shows the analgesic efficacy of preemptively-administered aboBoNT-A (Fig. 1B). Specifically, while none of saline-treated controls reached the threshold for the entire duration of the experiment, the aboBoNT-A-treated group there was an increase in the proportion of animals responding to WF of ≥ 26 g over time, from 1 to 4 animals between 1 and 6 h on Day 0 and from 2 to 6 from Day 1 to Day 5 (Fig. 1B).

DBS test

At baseline, sixteen days before surgery (Day − 16), all intact animals were distress-free (DBS 0; Fig. 1C). Animals remained distress-free after receiving either aboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) or saline, preemptively on Day − 15 via ID route and tested on Days − 13, -4 and − 1 (Fig. 1C). One hour after surgery however, saline treated controls began exhibiting a range of distress behaviors as they guarded the site of the incision and moved away when approached by the investigator (see Materials and methods; Fig. 1C). The DBS of saline-treated animals remained around 2, up to 6 h post-surgery on Day 0, while reaching DBS of 1 on Day 1 and negligible distress levels from Day 2 onwards (Fig. 1C). AboBoNT-A injection 15 days before surgery prevented the onset of distress starting at 1 h time-point (Fig. 1C). Specifically, aboBoNT-A-treated animals exhibited approximately 75% reduction in DBS (p < 0.01), indicative of negligible distress, up to Day 1, while being entirely distress-free on Days 2–7 (Fig. 1C).

The proportion of animals exhibiting low distress (DBS < 2) in each group also reflected marked anti-distress effects of preemptively administered aboBoNT-A 15 days before surgery (Fig. 1D). Specifically, while near all aboBoNT-A-treated animals had DBS below 2 on Day 0 (1, 2, 4, 6 h post-surgery), none of saline-treated controls reached this threshold up to 4 h post-surgery (Fig. 1D). Starting Day 1, low distress was observed in all animals (Fig. 1D).

Approaching test

As expected, at baseline (Day − 16), at the first encounter, intact naïve animals required approximately 120 s to approach the investigator (Fig. 1E). Preemptive administration of aboBoNT-A or saline on Day − 15 had no impact on rapid and similar reductions in latencies to approach in both groups when animals were tested on Days − 13, -10, -4 and − 1 (Fig. 1E). In fact, one day before surgery (Day − 1), animals in both groups required just a few seconds to initiate approach (Fig. 1E). Two hours following surgery, however, latencies to approach in saline-treated controls returned to values exhibited before habituation (i.e. around 120 s; Fig. 1E). Latencies to approach remained long (~ 90 s) up to Day 1 while declining to 30 s on Day 2 and returning to levels seen before surgery starting Day 3 (Fig. 1E). Animals with the history of aboBoNT-A treatment 15 days before surgery exhibited more than 70% reduction (p < 0.01) in latencies to approach 1 h following surgery and complete normalization of approaching behavior afterwords (Fig. 1E).

The proportion of animals exhibiting short latencies to approach (< 40 s) in each group also reflected remarkable normalization of approach behavior in response to preemptively administered aboBoNT-A 15 days before surgery (Fig. 1F). Specifically, among saline-treated animals, none exhibited short latencies 2 and 6 h post-surgery on Day 0 and only 1 did so on Day 1 (Fig. 1F). In contrast, among aboBoNT-A-treated animals, near all exhibited short latencies to approach starting 1 h following surgery (Fig. 1F).

Treatment 5 days before surgery

Von Frey test

At baseline (Day − 6), all intact animals exhibited normal mechanical sensitivity, as all but two animals responded to the WF of 60 g (Fig. 2A). The WF values did not change on Day − 1, four days after animals were treated with either aboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) or saline (Fig. 2A). However, on Day 0, 1 h following surgery, the WF of saline-treated controls was reduced to 2 g indicative of mechanical hypersensitivity (allodynia; Fig. 2A). The WF of saline-treated controls remained at this or lower levels up to Day 3, showing only a slow and minimal recovery to 6 g by Day 7 (Fig. 2A). The WF responses of animals treated preemptively with aboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) on Day − 5 were markedly and significantly higher than those in saline-treated controls for the entire post-operative period (Fig. 2A). Specifically, starting 1 h and up to Day 3 following surgery the WF of aboBoNT-A- treated animals were approximately 15 g, more than 7-fold higher (p < 0.01) than those in saline-treated controls (Fig. 2A). The WF of aboBoNT-A-treated animals reached 26 g by Day 4 and remained at this level for the remaining period (Days 5–7; Fig. 2A).

Effects of aboBoNT-A and saline administered 5 days before surgery on postsurgical pain-related behavioral responses in juvenile pigs. Animals received ID administration of aboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) or vehicle (saline) preemptively, 5 days before surgery (Day -5; blue arrows; n=5/group). Assessment of mechanical sensitivity/withdrawal force (WF; g, A, B), DBS (C, D) and latency to approach (sec; E, F) was done at multiple time-points before and after a full-skin-muscle incision and retraction surgery (red arrows). The green dotted line at 26 g on panel A represents the mechanical sensitivity threshold between normal mechanical sensitivity and mechanical hypersensitivity/allodynia. Each point on panels A, C, E represents the observed mean (+ SEM). Panel B shows the proportion of animals with normal mechanical sensitivity (WF ≥ 26 g) vs. hypersensitivity/allodynia (WF < 26 g). Panel D shows the proportion of animals exhibiting moderate to high distress (DBS ≥ 2) vs. those with minimal or no distress (DBS < 2). Panel F shows the proportion of animals that initiated approach in ≤40 s or those that took more than 40 s in the Approaching test. *p<0.01 vs. saline-injected animals. AboBoNT-A, abobotulinumtoxinA; ID, intradermal; DBS, distress behavior score; U, unit; WF, withdrawal force.

The proportion of animals in each group exhibiting normal mechanical sensitivity (≥ 26 g) was also significantly influenced by treatment (Fig. 2B). Following surgery, none of saline-treated controls reached this threshold for the entire period of testing (Fig. 2B). In contrast, a small proportion (1–2 in 5) of aboBoNT-A-treated animals reached this threshold between Days 2 and 7 (Fig. 2B).

DBS test

At baseline, six days before surgery (Day − 6), all intact animals were distress-free (DBS 0; Fig. 2C). Animals remained without any sign of distress after receiving aboBoNT-A or saline preemptively on Day − 5 and tested on Day − 1 (Fig. 2C). Starting 1 h after surgery, however, saline-treated controls began exhibiting distress behaviors that remained stable up to Day 6 (Fig. 2C). Animals treated with aboBoNT-A did not differ from saline-treated controls 1 h post-surgery, but exhibited a gradual, 50–75% reductions (p < 0.01) in DBS 2 to 6 h post-surgery (Fig. 2C). On Days 1 and 2, DBS of both aboBoNT-A and saline controls was around 2, whereas starting Day 3, unlike saline treated controls, aboBoNT-A treated animals showed near complete absence of distress for the rest of the experiment (Fig. 2C).

The proportion of animals exhibiting low distress (DBS < 2) in each group also reflected anti-distress effects of preemptively administered aboBoNT-A 5 days before surgery (Fig. 2D). Specifically, while none of saline treated controls had low DBS values up to 6 h post-surgery, there was a steady increase in the number of aboBoNT-A-treated animals with low distress from 1 (1 h) to 6 (4 and 6 h) on Day 0 (Fig. 2D). A smaller difference between the two groups remained on Days 1–7, as an overall higher proportion of aboBoNT-A-treated animals showed low distress in comparison to saline-treated controls (Fig. 2D).

Approaching test

At baseline (Day − 6), and on Day − 1, intact animals not yet familiar with the investigator required between 100 and 120 s to initiate approach (Fig. 2E). After surgery, in saline-treated animals the latencies to approach remained abnormally high as they continued to require 100 to 120 s until Day 6 (Fig. 2E). Preemptive treatment with aboBoNT-A on Day − 6 prevented the abnormal pattern of approaching behavior (Fig. 2E). Specifically, aboBoNT-A-treated animals exhibited up to 80% reductions (p < 0.01) in latencies to approach 2 and 6 h following surgery on Day 0 (Fig. 2E). The latencies to approach were approximately 70% lower in animals treated with aboBoNT-A than in saline-treated controls on Days 1 and 2, while reaching 80 to 90% reductions (p < 0.01) on Days 3–6 (Fig. 2E) .

The proportion of animals exhibiting short latencies to approach (< 40 s) in each group also reflected remarkable normalization of approach behavior in response to preemptively administered aboBoNT-A 5 days before surgery (Fig. 2F). Specifically, almost none of saline-treated animals exhibited short latencies to approach up to Day 6 (Fig. 2F). In contrast, 4 out 5 animals treated with aboBoNT-A exhibited short latencies to approach for the most part of the experiment (Fig. 2F).

Treatment 1 day before surgery

Von frey test

At baseline (Day − 2) and on Day − 1, mechanical sensitivity of intact animals was normal (WF 60 g; Fig. 3A). One hour after surgery, however, both saline and aboBoNT-A treated animals responded to the WF of 2 g, indicative of mechanical hypersensitivity (allodynia), which remained stable 2, 4 and 6 h following surgery (Fig. 3A). On Days 1 and 2, aboBoNT-A-treated animals showed 5-fold increases (p < 0.05) in WF in comparison to saline-treated controls (Fig. 3A). The WF values of aboBoNT-A-treated animals continued to increase thereafter as they reached 26 g (p < 0.01) on Day 3 and exceeded those on Days 4–7 (Fig. 3A).

Effects of aboBoNT-A and saline administered 1 day before surgery on postsurgical pain-related behavioral responses in juvenile pigs. Animals received ID administration of aboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) or vehicle (saline) preemptively, 1 day before surgery (Day -1; blue arrows; n=6/group). Assessment of mechanical sensitivity/withdrawal force (WF; g, A, B), DBS (C, D) and latency to approach (sec; E, F) was done at multiple time-points before and after a full-skin-muscle incision and retraction surgery (red arrows). The green dotted line at 26 g on panel A represents the mechanical sensitivity threshold between normal mechanical sensitivity and mechanical hypersensitivity/allodynia. Each point on panels A, C, E represents the observed mean (± SEM). Panel B shows the proportion of animals with normal mechanical sensitivity (WF ≥ 26 g) vs. hypersensitivity/allodynia (WF < 26 g). Panel D shows the proportion of animals exhibiting moderate to high distress (DBS ≥ 2) vs. those with minimal or no distress (DBS < 2). Panel F shows the proportion of animals that initiated approach in ≤40 s or those that took more than 40 s in the Approaching test. *p<0.01 vs. saline-injected animals. AboBoNT-A, abobotulinumtoxinA; ID, intradermal; DBS, distress behavior score; U, unit; WF, withdrawal force.

The proportion of animals with normal mechanical sensitivity (i.e. WF ≥ 26 g) in each group also reflected marked, but delayed analgesic effects of preemptively administered aboBoNT-A on Day − 1 (Fig. 3B). Specifically, as none of saline-treated controls reached the threshold throughout the study, between 2 and 5 aboBoNT-A-treated animals exhibited normal mechanical sensitivity on Days 3 to 7 (Fig. 3B).

DBS test

At baseline (Day − 2) and on Day − 1 all animals were distress-free (Fig. 3C). However, both saline- and aboBoNT-A-treated animals began exhibiting distress behaviors of identical magnitude (DBS 2) when tested 1, 2, 4 and 6 h after surgery (Fig. 3C). The level of post-surgical distress in saline-treated controls remained stable through Day 2, while declining subsequently to milder distress (DBS 1) on Days 4 through 7 (Fig. 3C). While there was a trend of earlier decline in DBS in aboBoNT-A treated animals, no statistical difference between the groups was detected at any of the timepoints in the study (Fig. 3C).

The proportion of animals with DBS < 2 in each group did not differ markedly between saline- and aboBoNT-A-treated animals (Fig. 3D). Specifically, none with either treatment reached this threshold up to 6 h post-surgery, while starting either Day 1 (aboBoNT-A treatment) or Day 3 (saline treatment) near all animals were distress-free (Fig. 3D).

Approaching test

As expected, intact, naïve animals not yet familiar with the investigator were slow to initiate approach when first tested on Day − 1 (Fig. 3E). Two and six hours following surgery (Day 0), and on Day 1 there were virtually no changes in either group, as animals continued exhibiting long latencies to approach (Fig. 3E). Starting Day 2, we observed a gradual decline in the latencies to approach, but the rate of decline was mild and similar in two groups (Fig. 3E).

Similarity between saline- and aboBoNT-A-treated animals in approach behavior was also captured in the proportion of animals exhibiting fast (≤ 40 s) latencies to approach (Fig. 3F). None in either saline- or aboBoNT-A-treated groups reached this threshold up to Day 1, whereas only a few (1–2 out of 6) did so on Days 2–6 (Fig. 3F).

Part B

ID administration

Von Frey test

At baseline, 16 days before surgery (Day − 16), all intact animals exhibited normal mechanical sensitivity, as they responded to the WF of 60 g (Fig. 4A). The mechanical sensitivity remained normal after animals received ID injection of either aboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) or saline on Day − 15 and were tested on Days − 10 and − 4 (Fig. 4A). As expected, a marked reduction in the WF of saline-treated controls occurred after surgery, as they responded to the WF of 2 g or lower at all time-points on Day 0 (i.e. 1, 2, 4, and 6 h following surgery; Fig. 4A). Mechanical hypersensitivity of saline treated animals remained stable on D2 and D3 and was followed by a slow and mild recovery to the WF of approximately 5 g by Day 7 (Fig. 4A). In contrast to saline treated controls, animals treated with aboBoNT-A (200 U/day) preemptively on Day − 15 exhibited markedly and significantly higher WF values for the entire post-operative period (Fig. 4A). Specifically, 1 to 6 h after surgery (Day 0) and on Day 1, the WF of aboBoNT-A-treated animals were 5 to 7-fold higher (p < 0.01) than that in saline-treated controls (Fig. 4A). On Days 2 to 7 the WF of aboBoNT-A-treated group approached or exceeded 26 g (Fig. 4A).

Effects of aboBoNT-A and saline administered 15 days before surgery on postsurgical pain-related behavioral responses in juvenile pigs. Animals received ID administration of aboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) or vehicle (saline) preemptively, 15 days before surgery (Day-15; blue arrows; n=6/group). Assessment of mechanical sensitivity/withdrawal force (WF; g, A, B), DBS (C, D) and latency to approach (sec; E, F) was done at multiple time-points before and after a full-skin-muscle incision and retraction surgery (red arrows). The green dotted line at 26 g on panel A represents the mechanical sensitivity threshold between normal mechanical sensitivity and mechanical hypersensitivity/allodynia. Each point on panels A, C, E represents the observed mean (+ SEM). Panel B shows the proportion of animals with normal mechanical sensitivity (WF ≥ 26 g) vs. hypersensitivity/allodynia (WF < 26 g). Panel D shows the proportion of animals exhibiting moderate to high distress (DBS ≥ 2) vs. those with minimal or no distress (DBS < 2). Panel F shows the proportion of animals that initiated approach in ≤40 s or those that took more than 40 s in the Approaching test. *p<0.01 vs. saline-injected animals. AboBoNT-A, abobotulinumtoxinA; ID, intradermal; DBS, distress behavior score; U, unit; WF, withdrawal force.

The proportion of animals exhibiting normal mechanical sensitivity in each group also shows the analgesic effect of aboBoNT-A treatment (Fig. 4B). Specifically, while none reached the threshold of 26 g among saline-treated controls for the entire duration of the study, a few of the aboBoNT-A-treated animals began exhibiting normal mechanical sensitivity starting Day 1 (Fig. 4B). Starting Day 5 all aboBoNT-A-treated animals exhibited normal mechanical sensitivity (Fig. 4B).

DBS test

At baseline, sixteen days before surgery (Day − 16), all intact animals were distress-free (DBS 0; Fig. 4C). Animals remained distress-free after they were injected with aboBoNT-A or saline and tested on Days − 10 and − 4 (Fig. 4C). One to four hours after surgery, however, saline-pretreated animals exhibited distress behaviors (DBS 2), while animals treated with aboBoNT-A exhibited more than 50% reduction (p < 0.01) in DBS 1 and 2 h following surgery and a similar trend 4 and 6 h following surgery (Fig. 4C). Starting Day 1, as the DBS of saline-treated controls declined to 1, the two groups exhibited similar distress profiles and similar rates of reductions in DBS until Day 7 (Fig. 4C).

The proportion of animals with low distress (DBS < 2) was markedly different in two groups up to 4 h post-surgery (Fig. 4D). During this period all saline-treated animals showed DBS ≥ 2, whereas 4 out of 6 aboBoNT-A-treated animals showed low distress. The difference between the two groups disappeared starting 6 h post-surgery, as we observed gradual increase in low DBS animals in the saline-treated group (Fig. 4D).

Approaching test

As expected, at baseline (Day-16), at the first encounter, intact animals approached the investigator in 120 s (Fig. 4E). Administration of aboBoNT-A or saline on Day − 15 had no impact on rapid and similar reductions in latencies to approach in both groups when animals were tested on Days − 10 and − 4 (Fig. 4E). After surgery, however, there was a dramatic increase in latencies to approach in saline-treated animals, as they returned to pre-habituation levels of responding (120 s) when tested 2 and 6 h post-surgery (Fig. 4E). Latencies to approach of saline-treated controls were intermediate (40 to 60 s) on Days 1–3, while normalizing from Day 4 onwards (Fig. 4E). Preemptive treatment with aboBoNT-A 15 days before surgery via ID route, resulted in more than 80% reduction in latency to approach (p < 0.01) in comparison to saline treatment 2 and 4 h following surgery (Fig. 4E). The approach behavior of aboBoNT-A-treated animals remained normal also for the remaining of the study (Days 1–7; Fig. 4E).

The proportion of animals with short latencies to approach the investigator (≤ 40 s) was markedly different between saline and aboBoNT-A groups up to Day 3 (Fig. 4F). Specifically, among saline-treated controls, none showed short latencies 2 and 6 h post-surgery, while only 2 out of 6 animals did so on Days 1–3 (Fig. 4F). In contrast, among aboBoNT-A-treated animals, between 4 and 6 exhibited short latencies during the same period (Fig. 4F). Starting Day 4, all animals were exhibiting short latencies to approach in both groups (Fig. 4F).

IM administration

Von frey test

At baseline, sixteen days before surgery (Day − 16), all intact animals exhibited normal mechanical sensitivity, as they responded to the WF of 60 g (Fig. 5A). The mechanical sensitivity remained normal after animals received treatment with either aboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) or saline via IM route and tested on Days − 10 and − 4 (Fig. 5A). However, 1 h following surgery on Day 0, saline and aboBoNT-A-treated animals responded to the WF of 2 g or lower, indicative of mechanical hypersensitivity (i.e. allodynia; Fig. 5A). The WF responses remained stable in both groups, exhibiting only mild, slow and similar increases to approximately 5 g by Day 7 (Fig. 5A). Among animals that received preemptive treatment with either aboBoNT-A or saline via IM route, none reached the WF of 26 g after surgery (Fig. 5B).

Effects of aboBoNT-A and saline administered 15 days before surgery on postsurgical pain-related behavioral responses in juvenile pigs. Animals received IM administration of aboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) or vehicle (saline) preemptively, 15 days before surgery (Day-15; blue arrows; n=6/group). Assessment of mechanical sensitivity/withdrawal force (WF; g, A, B), DBS (C, D), and latency to approach (sec; E, F) was done at multiple time-points before and after a full-skin-muscle incision and retraction surgery (red arrows). The green dotted line at 26 g on panel A represents the mechanical sensitivity threshold between normal mechanical sensitivity and mechanical hypersensitivity/allodynia. Each point on panels A, C, E represents the observed mean (+ SEM). Panel B shows the proportion of animals with normal mechanical sensitivity (WF ≥ 26 g) vs. hypersensitivity/allodynia (WF < 26 g). Panel D shows the proportion of animals exhibiting moderate to high distress (DBS ≥ 2) vs. those with minimal or no distress (DBS < 2). Panel F shows the proportion of animals that initiated approach in ≤40 s or those that took more than 40 s in the Approaching test. *p<0.01 vs. saline-injected animals. AboBoNT-A, abobotulinumtoxinA; IM, intramuscular; DBS, distress behavior score; U, unit; WF, withdrawal force.

DBS test

At baseline, sixteen days before surgery (Day − 16) all animals were distress-free (DBS 0; Fig. 5C). Animals remained distress-free after receiving either aboBoNT-A or saline preemptively on Day − 15 via ID route and testing on Days − 10 and − 4 (Fig. 5C). One hour after surgery, however, both groups began exhibiting a range of distress behaviors (DBS 2) that remained stable up to Day 2 (Fig. 5C). Starting Day 3, distress behaviors declined gradually and similarly in both groups (Fig. 5C). The proportion of animals with low distress was also similar in two groups (Fig. 5D). Specifically, while almost none from either groups exhibited DBS of ≤ 2 up to Day 3, near all animals were distress-free starting Day 4 (Fig. 5D).

Approaching test

As expected, at baseline (Day-16), at the first encounter, intact animals approached the investigator in 120 s (Fig. 5E). Preemptive administration of either aboBoNT-A or saline on Day − 15 via IM route had no impact on a rapid and similar decline in latencies to approach when animals were tested on Days − 10 and − 4 (Fig. 5E). Two hours following surgery, however, both groups exhibited rapid and similar increases in latencies to approach to the pre-habituation levels (Fig. 5E). The latency to approach the investigator remained high and similar in both groups up to D3, while declining rapidly and similarly to normal levels between Days 3 and 4 (Fig. 5E). The proportion of animals exhibiting short latencies to approach were also similar in two groups as almost none reached the 40 s threshold in either group until Day 2 (Fig. 5F). Starting Day 3, there were steady and similar increases in the proportion of animals with short latencies to approach in both groups (Fig. 5F).

SC administration

Von frey test

At baseline, sixteen days before surgery (Day − 16) all intact animals exhibited normal mechanical sensitivity (WF 60 g; Fig. 6A). AboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) or saline, injected preemptively on Day − 15 via SC route, had no effect on mechanical sensitivity when animals were tested on Days − 10 and − 4 (Fig. 6A). One hour after surgery, however, both groups responded to the WF of approximately 2 g, indicative of mechanical hypersensitivity (i.e. allodynia; Fig. 6A). These values remained low and similar up to Day 3 in both groups, while showing a mild, slow and similar recovery to 6 g by Day 7 (Fig. 6A). Among aboBoNT-A- or saline-treated animals none responded to the WF 26 g for the entire duration of the study (Fig. 6B).

Effects of aboBoNT-A and saline administered 15 days before surgery on postsurgical pain-related behavioral responses in juvenile pigs. Animals received SC administration of aboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) or vehicle (saline) preemptively, 15 days before surgery (Day-15; blue arrows; n=6/group). Assessment of mechanical sensitivity/withdrawal force (WF; g, A, B), DBS (C, D) and latency to approach (sec; E, F) was done at multiple time-points before and after a full-skin-muscle incision and retraction surgery (red arrows). The green dotted line at 26 g on panel A at represents the mechanical sensitivity threshold between normal mechanical sensitivity and mechanical hypersensitivity/allodynia. Each point on panels A, C, E represents the observed mean (+ SEM). Panel B shows the proportion of animals with normal mechanical sensitivity (WF ≥ 26 g) vs. hypersensitivity/allodynia (WF < 26 g). Panel D shows the proportion of animals exhibiting moderate to high distress (DBS ≥ 2) vs. those with minimal or no distress (DBS < 2). Panel F shows the proportion of animals that initiated approach in ≤40 s or those that took more than 40 s in the Approaching test. *p<0.01 vs. saline-injected animals. AboBoNT-A, abobotulinumtoxinA; SC, subcutaneous; DBS, distress behavior score; U, unit; WF, withdrawal force.

DBS test

At baseline, sixteen days before surgery (Day − 16), all intact animals were distress-free (DBS 0; Fig. 6C). Animals remained distress-free after receiving either aboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) or saline, preemptively on Day − 15 via SC route and tested on Days − 10 and − 4 (Fig. 6C). Following surgery, however, there was a rapid and similar onset of distress behaviors (DBS 2) in both groups 1 h following surgery (Fig. 6C). The DBS remained stable in both groups until Day 2 and gradually declined thereafter (Fig. 6C). The rate of DBS decline was somewhat faster in aboBoNT-A-treated animals than in saline-treated controls on Days 2 and 3, but the difference between the groups did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 6C). Starting Day 4, the DBS values and the rate of decline were virtually identical in two groups (Fig. 6C). There was also no marked difference in the proportion of distress-free animals present in two groups (Fig. 6D). Specifically, as almost none had DBS of < 2 up to Day 3 across both groups, there was a steady increase in the number of distress-free animals thereafter and by Day 6 all animals were distress-free (Fig. 6D).

Approaching test

At baseline (Day − 16), at the first encounter, intact animals approached the investigator in approximately 120 s (Fig. 6E). Preemptive administration of aboBoNT-A or saline on Day − 15 had no impact on rapid and similar reductions in latencies to approach in both groups when animals were tested on Days − 10 and − 4 (Fig. 6E). Following surgery, however, both groups exhibited rapid and similar increases in latencies to approach to their pre-habitation levels (120 s; Fig. 6E). The latencies to approach remained high and similar in both groups up to Day 3, while declining gradually thereafter and reaching expected values of less than 10 s starting Day 5 (Fig. 6E). The proportion of animals exhibiting short latencies to approach (< 40 s) were also similar in two groups (Fig. 6F). Specifically almost none showed short latencies to approach up to Day 3, followed by a steady increase in animals with short latencies, as they reached 100% by Day 5 in both groups (Fig. 6F).

Open field test

Part A AboBoNT-A (200U/animal) or saline, injected preemptively on Day − 15 via ID route had no effect on locomotor activity in the Open Fild test when animals were tested on Days − 10, -4, and − 1 (Fig. S1A). On Day 1, (but not Day 5), locomotor activity of aboBoNT-A-treated animals was higher, as a trend, than that in saline-treated controls (Fig. S1A). Animals treated with either aboBoNT-A or saline on Day − 15 also did not differ in the percentage of time spent in the central compartment of the Open field arena, when assessed before surgery on Days − 10, -4 and − 1 (Fig. S1B). After surgery, however, on Days 1 and 5, aboBoNT-A treated animals spent near 4-fold more time (p < 0.01) in the center of the arena, than saline-treated controls (Fig. S1B).

AboBoNT-A (200U/animal) or saline, injected preemptively on Day − 5 via ID route had no effect on locomotor activity in the Open Fild test when animals were tested on Days − 1, 1, and 5 (Fig. S1C). The two groups also did not differ in the percentage of time spent in the center of the arena assessed on these days (Fig. S1D).

AboBoNT-A (200U/animal) or saline, injected preemptively on Day − 1 via ID route had no effect on locomotor activity in the Open Fild test when animals were tested on Days 1 and 5 (Fig. S1E). The two groups also did not differ in the percentage of time spent in the center of the arena on these days (Fig. S1 F).

Part B AboBoNT-A (200U/animal) or saline, injected preemptively on Day − 15 via ID route had no effect on locomotor activity in the Open Fild test when animals were tested on Days − 13, -10, -4, and − 1 before surgery and Days 0, 1, 5 and 7 following surgery (Fig. S1A). (Fig. S2A). The two groups were also similar in the percentage of time spent in the center of the arena on these days (Fig. S2B).

AboBoNT-A (200U/animal) or saline, injected preemptively on Day − 15 via IM route had no effect on locomotor activity in the Open Fild test when animals were tested on Days − 13, -10, -4, and − 1 before surgery and Days 0, 1, 5 and 7 following surgery (Fig. S2C). The two groups were also similar in the percentage of time spent in the center of the arena on these days (Fig. S2D).

AboBoNT-A (200U/animal) or saline, injected preemptively on Day − 15 via SC route had no effect on locomotor activity in the Open Fild test when animals were tested on Days − 13, -10, -4, and − 1 before surgery and Days 0, 1, 5 and 7 following surgery (Fig. S2E). The two groups were also similar in the percentage of time spent in the center of the arena on these days (Fig. S2F).

Clinical signs and body weight

We did not observe any clinical signs or signs of limb paralysis throughout both parts, A and B, of the study.

Part A The two groups to be injected with either aboBoNT-A or saline were similar in the initial body weight, whereas after treatment aboBoNT-A-treated animals showed a trend of faster weight gain in comparison to saline treated controls (Table S1). The body weight gain was similar in animals that received aboBoNT-A or saline injection on Day − 5 as well as in animals that were treated on Day − 1 (Table S1).

Part B Administration of aboBoNT-A on Day − 15 via either ID, IM or SC routes had no effect on body weight gain (Table S2).

Wound inflammation

Daily clinical evaluation of wounds showed that inflammation-related swelling was absent in all animals in both parts A and B (Data not included). Mild redness was observed in one aboBoNT-A treated animal in part A and in two animals (one from each treatment group) in part B (Data not included).

Discussion

Post-operative pain management aims to minimise patient discomfort, facilitate early mobilisation and functional recovery, and prevent acute pain developing into chronic pain24. Extensive tissue damage in major operations causes immediate changes in the endocrine system and central, peripheral, and sympathetic nervous systems, and stimulate catabolic hormone release including cortisol, glucagon, growth hormone, and catecholamine, resulting in compromised immunity, increased oxygen demand, and higher strain on the cardiovascular system. Surgery causes tissue injury typically resulting in acute pain which should resolve during the healing process. Pain is a multidimensional experience, personalized to each patient and surgical procedure. If severe postoperative pain is managed inadequately under these circumstances, the surgery-induced responses can be exacerbated, posing a serious danger to patients. The perfect analgesic drug does not exist and postoperative pain management involves multimodal analgesia often combined with non-pharmacological therapies such as cognitive behavioural therapy. Multimodal analgesia includes opioids, gabapentinoids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and paracetamol. Available pain-reducing drugs are often associated with poor tolerability, unfavourable side effects and concerns over long-term safety and abuse potential, as well as inconvenience of use, which limit their use25. An effective “priming” procedure before elective surgery, based on acute intradermal injections of aboBoNT-A, offers an opportunity to effectively prevent or minimize post-surgical pain, improve emotional wellbeing and reduce reliance on existing pain medication.

This is a two-part, preclinical proof-of-concept study assessing whether aboBoNT-A administered in intact, naïve, juvenile pigs, preemptively, before surgery can effectively prevent the onset of post-surgical pain, reduce pain-related distress and normalize social behavior. In a framework of testing this hypothesis and with the goal to provide a valuable guidance to future clinical studies, we performed a systematic evaluation of the key experimental variables for optimal analgesic efficacy of aboBoNT-A following surgery. Specifically, aboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) or saline injected via ID route across ten injection points (20 U/point) around the anticipated surgical incision on the lower back of intact animals preemptively 15, 5, or 1 day before surgery to identify the most optimal pre-surgical pretreatment time for post-surgical analgesic efficacy (Part A). In a follow-up, aboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) or saline were administered via ID, IM, or SC routes across ten injection points (20 U/point) around the anticipated surgical incision in intact animals, 15 days before surgery to identify the most optimal route of administration (Part B). The data obtained in this study suggest that preemptive treatment 15 or 5 days (to lesser extent) before surgery using ID route represents the most optimal injection conditions for robust analgesic efficacy of aboBoNT-A in post-surgical pain and associated anxiety/depression-like reactivity. We found only minor differences between the analgesic profiles of aboBoNT-A delivered 15 and 5 days before surgery, whereas injections made 1 day before surgery were markedly less effective. In another important outcome of this study, aboBoNT-A delivered via IM or SC routes fully lacked efficacy in post-surgical pain.

The current model of post-surgical pain in juvenile pigs, a well-validated translational model, is a model of choice for systematic evaluation of locally administered aboBoNT-A’s injection conditions in post-surgical pain. Firstly, pigs are viewed as a good preclinical model for multiple biomedical applications, as their general anatomy, physiology and organ size ratio is similar to those in humans26. Secondly, the pig skin is remarkably similar to human skin in terms of their structure, innervation, immune response and post-incisional healing27,28. The pig skin is well suitable for intradermal injections, that are virtually impossible to administer in rodents. Thirdly, pigs are highly social animals, with a rich behavioral repertoire, well-developed cognitive abilities and affective states29. This permits evaluation of the impact of post-surgical pain on emotional reactivity and social behavior on the one hand and assessment of the effects of pre-surgical affective state on post-surgical pain and pain-induced anxiety/depression on the other30,31. Furthermore, pigs are gyrencephalic mammals similar to humans and most of the brain regions are well comparable in terms of structure, development and vascularization26. Thus, the model offers and opportunity of in-depth exploration of brain mechanisms mediating analgesic as well as anxiolytic/antidepressant effects of aboBoNT-A in post-surgical pain32.

It needs to be noted that despite the fact that, in the current model, the incision is placed on the lower flank of the animal in vicinity to the spine, it was developed as a model relevant to soft tissue surgeries, such as hernia or mastectomy. We intentionally avoided placing the incision on the abdomen in order avoid the risk to infections and poor healing of the wound, which would have been markedly higher if the wound repeatedly touched the ground. Also, positioning the incision on the abdomen, rather than the flank, would made it completely inaccessible for von Frey testing. The model has shown relevance for studies of post-operative analgesia across multiple types of surgeries. For example, the model successfully predicted the enhanced analgesic activity of formulations of bupivacaine plus meloxicam over formulations of bupivacaine alone in a post-surgical pain following bunionectomy surgery33.

As done in our previous study23, we chose SMIR surgery over a full-skin incision surgery, as it better mimics surgeries performed in the clinic. Mechanical hypersensitivity detected in the von Frey test and guarding behavior exhibited after SMIR surgery are considered as surrogates for evoked, movement-related pain and non-evoked, resting pain, respectively in humans34,35 and rodents36. Multiple signs of distress, including reduced social interaction, withdrawal when approached, distress vocalizations, on the other hand, are considered as surrogates for pain-related anxiety or depression seen in human patients and in rodent models of post-surgical pain. Assessment of the approaching responses towards the familiar investigator offers another view of the animals’ affective state. Specifically, with repeated exposure, there is a rapid reduction in latencies to approach the investigator. This process appears to reflects formation of social bond between the animal and the human, which may have a broad positive impact on the animal’s affective state37. Following surgery, there is a transient pain-mediated disruption of the bond, as the latencies to approach change dramatically, returning to the pre-habituation levels in saline injected control animals. These changes in behavior are likely to reflect pain-related anxiety- and depression-like reactivity.

The findings of the study support the hypothesis that preemptive administration of aboBoNT-A before surgery can shorten the time of onset of its analgesic activity and effectively reduce or fully prevent the expression of post-operative pain. ID injections of aboBoNT-A 15 days before surgery delivered the best analgesic outcome across three pretreatment periods. This pretreatment condition was evaluated in two independent cohorts, one in each part of the study, performed several months apart. In both cohorts, the analgesic magnitude of aboBoNT-A was overall similar. Specifically, at the earliest time-point after surgery (1 h), aboBoNT-A treated animals showed 5 to 7-fold higher WF responses in comparison to saline treated controls in both cohorts. This can be interpreted as a marked reduction of mechanical allodynia from severe to mild. The WF values continued to increase in two cohorts over time reaching 26 g and higher WF values, albeit with a slightly different rate. The SMIR-associated DBS, a composite score, which includes behaviors relevant to non-evoked pain and to anxiety or depression-like reactivity, had magnitude of 2 and duration of 24 to 48 h in both cohorts. ID injection of aboBoNT-A injection 15 days before surgery either fully prevented the onset of pain-related distress (part A) or significantly reduced it (part B). The latency to approach, measuring the time required for the animal to initiate approach towards the investigator, offered an opportunity to study the effects of post-surgical pain on social bonding and behavior. The rate of reduction in latencies before surgery, signifying a remarkably rapid process of social bonding between the animals and the human, was similar in two cohorts. While, following surgery, we observed a full disruption of the social bond and abnormal avoidance of the investigator in saline injected controls, it was fully preserved in aboBoNT-A treated animals in both cohorts.

Evaluation of the 5 day pretreatment condition provided additional insights on analgesic efficacy of preemptively administered aboBoNT-A. On the one hand, the overall analgesic profile of aboBoNT-A injected 5 days before surgery was found to be nearly identical to that seen with 15 days pretreatment. Specifically, in both pretreatment conditions, aboBoNT-A effectively reduced mechanical allodynia from 1 h post-surgery until the end of the study on Day 7. On the other hand, fewer animals reached the threshold for normal mechanical sensitivity and low distress in animals pretreated with aboBoNT-A 5 days before surgery than those pretreated 15 days before surgery. The overall similarity in analgesic efficacy of aboBoNT-A observed following these pretreatment periods suggests that the optimal period for maximal efficacy of aboBoNT is somewhat broad acompassing 5 to 15 days. If confirmed in a clinical setting, this could offer a valuable flexibility to patients and anesthesiologists in planning the preemptive BoNT “priming” procedure ahead of surgery. Here, reviewing the profile of animals treated preemptively 5 days before surgery, we confirm that the efficacy aboBoNT-A in reducing post-surgical distress and normalizing social behavior can be as long lasting as the reversal of mechanical allodynia. We can speculate that individual variability in baseline emotional reactivity combined with their pre-surgical experience made the current cohort’s emotional response to be more sensitive to surgery. Based on prolonged post-surgical distress and anxiety or depression-like responses, the cohort can be considered a model of “catastrophizing” phenotype seen in some patients. Additional studies are needed to further explore how the pre-surgical emotional shapes the animals’ pain as well as pain-related distress, anxiety- and depression-like reactivity.

In the current study, we had no concern about the risk of aboBoNT-A-induced paralysis that could impact the interpretation of its analgesic efficacy in this study. Firstly, out of three doses of aboBoNT-A (100, 200, and 400 U/animal) used in the previous study, none of which resulted in any signs of paralysis, we selected the intermediate one, 200 U/animal, for the current study. Secondly, aboBoNT-A-injected animals showed no signs of systemic or local adverse effects, while gaining body weight at or above the levels seen in saline-treated controls. Thirdly, activity in the open field test, which was performed at multiple timepoints, did not suggest any motor impairment due to paralysis.

These results confirm and expand our previous findings that peripherally administered aboBoNT-A in juvenile pigs can reduce not only signs of evoked and non-evoked pain, but also pain-related anxiety/depression-like reactivity and normalize social behavior23. Specifically, aboBoNT-A treatment prevents pain-related deficits in social interaction with the other animals in the pen and prevents pain-related abnormalities in approaching behavior, shown by saline treated controls. Normalization of intra- and interspecies social behaviors can be considered as a surrogate for improved mood and emotional wellbeing in humans. In support of translational validity of these data, there is a growing evidence of an anxiolytic and antidepressant-like activity of BoNT-A in clinical setting. In fact, there have been 10 clinical trials that showed antidepressant effect of onabotulinumtoxinA (onaBoNT-A; Botox) in patients injected into their frown musculature (facial muscles of the glabellar area)38. These effects of onaBoNT-A are long-lasting (up to 24 weeks;39) and appear to be independent from the effects on the improvement in the appearance of the glabellar lines40. Also, onaBoNT-A reduced anxiety as well as depression in patients with hemifacial spasm and patients with benign essential blepharospasm for up to 2 months41,42. Furthermore, onaBoNT-A administered to patients with hyperhidrosis resulted in marked reduction of social phobia, anxiety and depression43. The clinical efficacy of onaBoNT-A in depression and anxiety is well aligned with its anxiolytic and antidepressant-like efficacy in animal models. For example, in a mouse model of trigeminal neuralgia based on chronic constriction injury of the distal infraorbital nerve, unilateral injection of BoNT-A into the whisker pad, reduced bilateral mechanical hypersensitivity, anxiety and depression-like responsiveness44. Also, BoNT-A injected into the cheek, reduced depression-like behavior in a reserpine-induced Parkinson’s disease model in mice45.

In contrast to the effective post-operative analgesia seen with aboBoNT-A injections, in this study, 15 or 5 days before surgery, those made 1 day before surgery were associated with a delayed onset of activity and milder effects. Specifically, aboBoNT-A was inactive in the von Frey test on Day 0, as the effects only emerged on Day 1. AboBoNT-A also had a delayed and mild effect on DBS, while fully failing to normalize approaching latencies. Overall, these data suggest that the analgesic profile of aboBoNT-A injected 1 day before surgery is inferior not only to those seen with 15 or 5 days pretreatment time, but also to the profile obtained in our previous study23 following intraoperative injection of the same dose (200 U/animal), especially in measures of DBS and approaching behavior. We can speculate that the surgical procedure, performed within 24 h following aboBoNT-A injections, disrupted the retrograde transport of the molecule from the site of injection in the dermis to the spinal cord, causing fewer molecules to reach their target in its upper lamina as described in our previous study23 (see below).

An important outcome of this study in pigs is the discovery of complete lack of analgesic activity of aboBoNT-A in post-surgical pain when the injections are made using IM or SC routes. Animals injected with either aboBoNT-A or saline were virtually indistinguishable across all three pain-related behavioral readouts when the injections were made via IM or SC routes. These data suggest that injections of BoNT-A via IM or SC routes for alleviation of post-surgical pain in a clinical setting may need to be avoided.

Consistent with our previous findings, aboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) injected in intact animals around the anticipated incision was well-tolerated, as treated animals showed no clinical signs and were normal in terms of peripheral sensory afferent nerve function, locomotor activity and general behavior, affective state and social behavior. Specifically, aboBoNT-A injected animals were identical to saline injected controls in mechanical sensitivity, locomotor activity and body weight gain. Both aboBoNT-A and saline treated animals remained distress-free and exhibited normal reduction in latencies to approach the investigator, indicative of normal affective state. After surgery, as the level of wound inflammation was low and the level of wound healing was similar, the effects of aboBoNT-A on pain-related behavioral responses described here are not confounded by adverse effects or by differences in wound inflammation, healing process, suggesting that aboBoNT-A has a specific analgesic efficacy.

It is a limitation of the current study that it was performed with only male animals. Evaluation of efficacy of aboBoNT-A in both male and female animals could have revealed potential sex differences in post-surgical pain, pain-related distress and approaching behavior. Another limitation of the study is that it did not include IHC analysis of cleaved SNAP25 and pain-related biomarkers. In our previous study, we observed a clear presence of cleaved SNAP25 in the upper lamina of the lumbar spinal cord in aboBoNT-A injected animals and its absence in saline injected controls23. The question remains whether marked differences in analgesic profiles of aboBoNT-A obtained in ID vs. IM and SC seen across behavioral readouts would also be seen in cleaved SNAP25 in the upper lamina of the lumbar spinal cord. Also, another important question remains whether anxiolytic- or antidepressant-like efficacy of aboBoNT-A in post-surgical pain is driven by direct or indirect activity of aboBoNT-A in the brain of pigs.

In conclusion, in a pig model of post-surgical pain, preemptive administration of aboBoNT-A around anticipated surgical incision in intact animals via ID route 15 days before surgery delivers effective and prolonged post-surgical analgesia, reduces pain-related anxiety or depression and normalizes behavior. The analgesic activity of aboBoNT-A in post-surgical pain requires ID route of administration, as IM and SC injections lack efficacy. These data support further studies using the current model to explore the mechanisms that support analgesic and anxiolytic/antidepressant activity of aboBoNT-A. Standardized structured perioperative multimodal pain management strategies, Enhanced Recovery Pathways (ERPs), that minimize opioid use to promote postoperative recovery have and continue to be developed. These evolving pathways have strong supporting evidence and although “knowledge gaps and controversies remain”, a modality that has the potential to help post-operative analgesia and pain-related anxiety/depression would have a role. Importantly, our study supports subsequent clinical evaluation of preemptive ID aboBoNT-A injection before surgery, as an innovative approach for the effective, multimodal relief of post-surgical pain.

Materials and methods

Animals

Study was carried out on juvenile (8–10 weeks old), male Danish Landrace x Large White cross-bred domestic pigs (Sus scrofa), provided by Lahav Labs (Negev, Israel). Animals were castrated, had their teeth clipped and tails cut few days after birth in alignment with the standard practice in conventional pig breeding facilities. All animals were drug and test naïve and in good health as confirmed by an attending veterinarian. They were housed in smooth-walled pens (140 × 240 cm), three per pen and maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights on from 07:00 to 19:00 h) under a constant temperature (21 ± 2 °C) and humidity (55 ± 5%) throughout the acclimatization and testing periods. Animals were given a unique identification ear mark in the form of a four-digit number and were acclimated to the facility for 5 days before the study. Animals were provided with food (Dry Sows; Ct # 5420; Milobar; Oshrat, Israel) twice daily, water ad libitum and also received enrichment to root and chew on during the study. Animals weighed between 10 and 12 kg at the start of the habituation period.

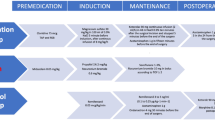

Study design

This was a two-part study. In part A, carried out between November and December 2018, we assessed the efficacy of preoperatively administered aboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) vs. saline in mechanical sensitivity, pain-related distress and approaching behavior and identified the most optimal pretreatment time (Table S3 ). AboBoNT-A or saline were administered either 15, 5, or 1 day before surgery via ID route (Table S3). In part B, carried out between May and June 2019, we identified the most optimal route of administration for the analgesic efficacy of preoperatively administered aboBoNT-A (Table S4). AboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) or saline were administered 15 days before surgery using either ID, intramuscular (IM) or subcutaneous (SC) routes. In each part we used 36 animals, divided into 3 separate cohorts.

Each cohort consisted of 12 animals. In each cohort animals were randomly allocated to aboBoNT-A- and saline-treated groups (n = 6/group). The sample size was decided based on 3Rs, provisional sample size from previous experiments performed with this model23 and a “common sense” approach46 linked to constrains associated with experimentation in large animal species, such as costs per animal and space for animal housing. Initially we used “The resource equation” to confirm that having two groups with 6 animals in each group was associated with E value that was between 10 and 20, recommended for reducing the chance of seeing a Type II error46. As our overall goal was to make results of the study as clinically-relevant as possible, we reduced the significance level (p < 0.01; see Statistical analysis). Further calculations of Cohen’s d values for 90% power assuming a two-sided t-test with 1% significance confirmed the current sample size.

As done in our previous study23, pain-related behavioral assessment involved a standard battery of behavioral tests including von Frey, Distress Behavior Score (DBS) and Approaching tests, performed in the home pen (see ‘Assessments’). We also performed the Open-field test and measured body weight at multiple time-points before and after surgery (Tables S3, S4). Wound inflammation and clinical signs were monitored daily on Days 1–7.

Part A. In Cohort 1, animals were injected with aboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) or saline (n = 6/treatment), ID, 15 days before surgery (Day − 15), after they were assessed for the baseline responsiveness within 24 h before treatment (Table S3). Animals were tested again on Days − 13, -10, -4 and − 1, Day 0 (1, 2, 4 and 6 h following surgery) and on Days 1–7 after surgery (Table S3). In Cohort 2, animals were injected with aboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) or saline (n = 6/treatment), ID, 5 days before surgery (Day − 5), after they were assessed for the baseline responsiveness within 24 h before treatment (Table S3). Animals were tested again on Day − 1, Day 0 (1, 2, 4 and 6 h following surgery) and Days 1–7 after surgery (Table S3). In Cohort 2, two animals (one from each treatment group), developed health complications unrelated to treatment during the study and had to be euthanized using humane methods. Therefore, their data were excluded from the analysis. Thus, there were 5 animals per group in Cohort 2 at the end of the study. In Cohort 3 animals were administered aboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) or saline (n = 6/treatment), ID, the day before surgery (Day − 1), after they were assessed for baseline responsiveness within 24 h before treatment (Table S3). Animals were tested again Day 0 (1, 2, 4 and 6 h following surgery) and on Days 1–7 after surgery (Table S3).

Part B. Here, we simplified the design used with animals treated on Day-15 in Part A. Specifically, animals in Cohort 1 received ID injections of aboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) or saline on Day − 15 and were tested on Days − 10, -4, Day 0 (1, 2, 4, and 6 h following surgery) and post-surgical Days 1–7 (Table S4). Animals in Cohort 2 and Cohort 3 received either intramuscular and subcutaneous injections, of aboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) and saline (n = 6/route/group), respectively, and their assessment was performed exactly as those in Cohort 1 (Table S4).

As done in our previous study23, behavioral tests were performed in the morning, at approximately 8:30 am (at least 1 h after the morning feed). The same investigator, blind to treatment, performed all behavioral testing in each phase. Specifically, the Approaching and the DBS tests, done first and second, respectively, were performed simultaneously in all three animals housed in the pen. The Approaching and the DBS tests were followed by the von Frey test performed individually without any restraint. Familiarity of the animal with the investigator ensured that the animal remained in proximity to the investigator during the test. On certain days the von Frey test was followed by the Open field test (Table S4). Wound inflammation was evaluated daily on Days 1–7. The body weight of animals was measured at regular intervals before and after surgery (Table S4).

All experimental procedures used in the study were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of MD Biosciences (Ness Ziona, Israel). The study registration numbers, IL-1-1-706-2352 and IL-1-1-706-2542, were assigned to Parts A and B, respectively. Studies were performed in full compliance with guidelines of the Israel National Ethics Committee, Committee for Research and Ethical Issues of the International Association for the Study of Pain47, and the US National Research Council Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Drug administration

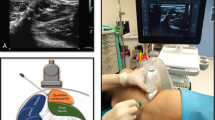

AboBoNT-A (Dysport) was obtained from Ipsen Limited (Wrexham, UK). Each vial containing 500 U of purified C. botulinum type A neurotoxin complex was reconstituted in saline (0.9% sodium chloride) to obtain the final concentration. Animals were anesthetized with a 5% isoflurane/oxygen (2–3 L/min) mixture using an anesthetic facemask (Stephan Akzent Color, Gackenbach, Germany). Before the injection, animals received a tattoo on their lower back, corresponding the length of the prospective incision (7 cm; Fig. 7A). The injector was blind to treatment and treatment allocation was concealed throughout the study. We assigned animals to aboBoNT-A (200 U/animal) or saline treatment following random allocation of holding pens to specific treatment condition. As a result, all three animals housed in a pen received the same treatment. Treatment was administered in 2 mL total volume split into ten injections (20 U in 0.2 mL/site) around the incision (Fig. 7A). Specifically, 4 injections, made approximately 2 cm apart, were administered within 0.5 cm from the tattooed line on each side (medial and lateral), while single injections were aimed at the rostral and caudal ends of the tattooed line (Fig. 7A). We used 30 G needles attached to 1-mL syringes (BD Micro Fine Plus; Becton Dickinson, Plymouth, UK) for all injections of aboBoNT-A or saline. To perform ID injections, needle was positioned at a low angle (< 10°) in relation to the body surface and injected 5 to 15 mm below the surface, also guided by the maintained resistance of the dermis. To perform SC injections, needle was positioned at a wider angle (45–60°) also guided by the lack of resistance of the subcutaneous space. The IM injection were performed at almost 90° with the aid of an M9 premium hand carried ultrasound system and L14-6Ns (linear) probe (Mindray Healthcare; Mahwah, USA), which allowed visualization of the needle entering the muscle.

Location of aboBoNT-A or saline injections and subsequent SMIR surgery in juvenile pigs. Schematic representation of ten aboBoNT-A or saline injection points (blue crosses) distributed around the tattooed line (red line) indicating the placement of the anticipated incision and the point of von Frey filament placement (yellow circle; panel A). Panel B is a photo of the wound after a SMIR surgery on the lower back of a representative animal (B). SMIR, full-skin-muscle incision and retraction.

Surgery

The SMIR surgery was performed as described previously23,48. The surgeon performing the surgery was blind to treatment. In the morning of the day of surgery (Day 0), pigs were anesthetized with a 5% isoflurane/oxygen (2–3 L/min) mixture with the aid of anesthetic facemask (Stephan Akzent Color, Gackenbach, Germany). The anesthesia permitted relatively quick recovery for the assessment of behavioral responsiveness 1 h after the surgery/treatment. An incision was made on the left side of the lower back, approximately 3 cm lateral and parallel to the spine (Fig. 7B). Before administering the incision, the area of the low back was scrubbed with antiseptic liquid (Polydine® solution, Dr. Fischer laboratories, Bnei Brak, Israel) and wiped with 70% ethanol. A 7-cm long, full skin thickness incision was made, including the fascia and the underlying muscle (gluteus medius) which was retracted to perform the incision. A sterile cover, disinfected with an antiseptic liquid (3% synthomycine), was placed around the incisional area. The fascia was sutured with 3 − 0 vicryl thread, while the skin was sutured with 3 − 0 silk thread (Assault UK Ltd., West Yorkshire, UK) using continuous suturing methods (Fig. 7B). Following the incision closure, animals received an intramuscular injection of an antibiotic, 4 mg/kg Marbocyl® (10% w/v; Vetoquinol UK Ltd., Buckingham, UK), into the neck. The animals were then returned to their pens for recovery and observation.

Assessments

Von Frey test

The von Frey test was performed to evaluate mechanical sensitivity before and after surgery as described previously23,48. Animals were not restrained during the test. We used a set of von Frey filaments (Ugo Basile, Gemonio, Italy), ranging from 1 g (diameter 0.229 mm and force 9.804 mN) to 60 g (diameter 0.711 mm and force 588.253 mN; Table S5). The von Frey filament was applied approximately 0.5 cm proximal to the middle of the tattooed/incisional line on the medial side (Fig. 7A). Each filament was applied to the same spot three times with the interval of 5 to 10 s. Withdrawal reaction was considered if the animal moved away its body from the stimulus or twisted its flank with or without tail wiggling. The latter, on its own, was not considered to be a sign of withdrawal reaction. If withdrawal from the filament did occur by the animal, a thinner filament was applied, whereas if withdrawal did not occur, a thicker filament was applied. Animals were excluded from the study if their WF responses at baseline were below 26 g. Only one animal was excluded from the study.

DBS test

The DBS test was performed to monitor a set of behaviors believed to be relevant for non-evoked, resting pain after surgery as described previously23,48. Specifically, we monitored 14 behaviors that are divided into seven categories (Table S6). These behaviors are either exhibited by normal, intact animals (score 0) or are expressed in association with ongoing pain, such as pain after surgery (score 1; Table S6). These behaviors were monitored and recorded as exhibited by the animal without particular order. The total DBS, the sum of the scores in each category, can range from 0 (normal; no distress) to 7 (severely distressed). The DBS test lasted approximately 3 min. As the total DBS for each animal never exceeded 3 (out of maximum 7), indicative of moderate distress at its maximum, a rescue analgesic was considered to be unnecessary.

Approaching test

We performed the Approaching test to measure non-evoked pain-related anxiety- or depression-like reactivity as done previously23. The basis of the Approaching test is a social bond that young pigs establish with their caretaker in the process of their daily interactions49. Juvenile pigs are slow to approach unfamiliar individuals. Repeated exposure to a familiar caretaker, results in remarkably rapid and robust reductions in time the animal requires to initiate approach. Following SMIR, however, seeking social interaction with the familiar caretaker is replaced with pain-triggered behavioral conflict between seeking and avoidance responses causing latencies to approach to increase. We measured the latency (sec) to approach the investigator entering their home-pen using a cut-off time of 120 s.

Open field test

The Open field test was performed as described previously23,50. Briefly, animals were individually led to the waiting area adjacent to the Open-field arena (2.5 × 4.7 × 1.6 m). After 10 s of waiting time, the door was opened and the test started after animal fully entered the arena. Locomotor activity was measured for 5 min with a CCTV camera suspended above the center of the arena. The data were analyzed with AnyMaze software (Stoelting Co, Dublin, Ireland). The total distance travelled (m) and the percentage of time spent in the center of the area were quantified.

Wound inflammation

Wound inflammation was scored based on two categories: redness (0- normal; 1- slight redness at the area of the incision; 2- spread redness) and swelling (0, no swelling; 1, slight swelling; 2, pronounced swelling). The final score for each animal is the sum of the scores in each category (max score = 4). The wound inflammation was scored once daily on Days 1 to 7.

Data analysis

Mechanical sensitivity data (von Frey test) were first transformed to quoted stimulus by a log transformation of the gram units multiplied by 10,000. The analysis includes a full factorial repeated measure mixed linear model. The fixed effects include treatment, time and their interaction while the random effects were estimated for animal nested in treatment and animal crossed with time nested in treatment. Tukey post hoc test was derived to compare any group at any time with any other (including itself over time). Analyses were performed using JMP®, Version 14 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.01.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to being used under license for the current study, but are available from the authors on reasonable request.

References

Gerbershagen, H. J. et al. Pain Intensity on the first day after surgery. Anesthesiology 118, 934–944 (2013).

Apfelbaum, J. L., Chen, C., Mehta, S. S. & Gan, T. J. Postoperative pain experience: results from a national survey suggest postoperative pain continues to be undermanaged. Anesth. Analg. 97, 534–540 (2003).

Lorentzen, V., Hermansen, I. L. & Botti, M. A prospective analysis of pain experience, beliefs and attitudes, and pain management of a cohort of Danish surgical patients. Eur. J. Pain. 16, 278–288 (2012).

Kharasch, E. D. Michael Brunt, L. Perioperative opioids and public health. Anesthesiology 124, 960–965 (2016).

Popoff, M. R. & Bouvet, P. Genetic characteristics of toxigenic Clostridia and toxin gene evolution. Toxicon 75, 63–89 (2013).

Pirazzini, M., Rossetto, O., Eleopra, R. & Montecucco, C. Botulinum neurotoxins: Biology, pharmacology, and toxicology. Pharmacol. Rev. 69, 200–235 (2017).

Tehran, D. A. Novel Botulinum Neurotoxins: Exploring Underneath. 7–9 (2018). https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins10050190

Sudhof, T. C. & Rizo, J. Synaptic vesicle exocytosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol. 3, a005637 (2011).

Lim, E. C. H. & Seet, R. C. S. Use of botulinum toxin in the neurology clinic. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 6, 624–636 (2010).

Matak, I. & Lacković, Z. Botulinum toxin A, brain and pain. Prog Neurobiol. 119–120, 39–59 (2014).

Matak, I., Bölcskei, K., Bach-Rojecky, L. & Helyes, Z. Mechanisms of Botulinum Toxin Type A Action on Pain. Toxins (Basel). 11, 459 (2019).

Kim, D., Lee, S. & Ahnn, J. Botulinum Toxin as a Pain Killer: players and actions in Antinociception. 2435–2453 (2015). https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins7072435

Dolly, J. O. & O’Connell, M. A. Neurotherapeutics to inhibit exocytosis from sensory neurons for the control of chronic pain. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 12, 100–108 (2012).

Durham, P. L., Cady, R., Cady, R. & Blumenfeld, A. J. Regulation of calcitonin gene-related peptide secretion from trigeminal nerve cells by Botulinum Toxin Type A: implications for Migraine Therapy. Headache 44, 35–43 (2004).

da Silva, L. B., Poulsen, J. N., Arendt-Nielsen, L. & Gazerani, P. Botulinum neurotoxin type a modulates vesicular release of glutamate from satellite glial cells. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 19, 1900–1909 (2015).