Abstract

The recent expansion of the interpretative scope of ferromagnetic resonance (FMR) experiments has resulted from recognizing the essential role of the curvature of the magnetic free energy landscape in data interpretation. This study applied that concept to reinterpret low-frequency FMR measurements on a yttrium iron garnet (YIG) thin film grown along the [111] axis of its crystalographic structure, perpendicularly to the film plane. Through machine learning, we have observed that the coefficients (referred earlier to as anisotropy constants and demagnetization constants) in the expansion of the magnetic free energy into a series may depend on resonance frequency. This observation complements the older approach that assumes fixed anisotropy constants. Moreover, it leads to a more precise understanding of the outputs of FMR experiments, which may also have implications for their future interpretations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The ferromagnetic resonance phenomenon is the basis of an experimental technique that measures the precessional motion of the magnetization vector of a ferromagnet in an external static magnetic field. This experimental technique is a powerful tool for analyzing the magnetic properties of ferromagnets and allows the determination of anisotropy constants, see, e.g.,1. Knowledge of these constants, in turn, enables the determination of the sample’s spatial distribution of the magnetic free energy at resonance.

Recent investigations2,3 have shed a new light on the interpretive possibilities of this technique. Rather than simply identifying anisotropy constant values, these studies have presented an analysis of the spatial distribution of the magnetic free energy of the sample at resonance resulting from its curvature and established the criterion of which terms (commonly called anisotropy constants and demagnetization constants) in its series expansion are necessary to interpret the FMR experiment correctly. This approach cross-validates numerical solutions of the Smit-Beljers (S-B) equation4,5,6,7, leading to an optimal characterization of the magnetic energy density dependence on resonance angles from an experimental point of view.

The role of yttrium iron garnet (YIG) in magnonics and spintronics is well-recognized (see, e.g.,8). Its diverse functions in spin manipulation, transport, and detection are driven by its unique magnetic (high Curie temperature and low magnetic damping), optical (transparency in the visible and infrared regions, high Faraday rotation), and transport (high dielectric constant and low microwave loss) properties. These distinctive characteristics make YIG invaluable for developing advanced spintronic devices and technologies. Understanding the spatial distribution of YIG’s magnetic free energy is just essential from the perspective of these applications.

This paper presents the reinterpretation of the results from a low-frequency FMR experiment on a YIG thin film9, using the concepts mentioned earlier and aiming to characterize the spatial distribution of free magnetic energy density properly. In this experiment, the [111] axis of the YIG crystal structure was positioned perpendicularly to the thin film, and only out-of-plane measurements have been reported. Interpreting such an experiment is a complex task because of the significant increase in anisotropy caused by demagnetization, which aligns with the direction of magnetocrystalline anisotropy. However, as we will show, the approach based on curvature analysis within machine learning is also highly effective for this measurement geometry.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In the second section, we revisit two phenomenological models of free magnetic energy for YIG. The third section presents an analysis of these models based on experimental data9 obtained in the [111] geometry. Finally, the article concludes with a summary.

Magnetic free energy

Two models of YIG’s magnetic free energy expansion

The sample is assumed to be a homogeneous, magnetically saturated domain, with magnetization M. The magnetic free energy of its unit volume is composed of Zeeman term \(F_Z\), demagnetization term \(F_D\), and magnetocrystalline anisotropy contributions - cubic \(F_C\) and uniaxial \(F_U\),

Dividing both sides of Eq. (1) by M and thus expressing free energy in terms of fictitious magnetic fields, one obtains

Let us remind the meaning of all the terms entering Eq. (2) shortly. The \(Zeeman \, f\!ield\) is given by

and the unit vectors are defined as usual, i.e.,

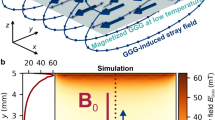

The experimental angles \(\theta _H\) and \(\phi _H\) are measured from the [111] and the [2-1-1] axes to the static magnetic field, respectively, see Fig. 1.

The geometry of the FMR experiment is described in the coordinate system attached to the YIG thin film ([2-1-1] [01-1] [111]), rather than that attached to the crystallographic axes of the YIG ([100][001][001]). The angles \(\theta _H\) and \(\phi _H\) represent the direction of the static magnetic field, while \(\theta\) and \(\phi\) represent the direction of the sample’s saturation magnetization \({\textbf{M}}\).

The \(demagnetizing \,f\!ield\) is given by

\({\alpha , \beta }=x, y, z\) and \(\mathcal {N}_{\alpha \beta }\) stands for the demagnetization tensor. In what follows we will take it into account two forms of the demagnetization tensor,

and

with the condition \(\mathcal {N}_x+\mathcal {N}_y+\mathcal {N}_z=1\). \(H_Z\) and \(H_D\) are determined in the experimental reference frame, that is, related to the axes [2-1-1], [01-1], and [111] as shown in Fig. 1. The FMR measurements9, being a subject of further analysis, were made on a thin epitaxial film of YIG growing along the [111] axis of the YIG crystal structure. The experimental angles \(\theta _H\) and \(\phi _H\) were measured from the [111] and the [2-1-1] axes to the static magnetic field. Calculating all components entering Eq. (1) in the coordinate system shown in Fig. 1 requires transforming \(H_C\) and \(H_U\) to this coordinate system.

The term \(H_C\) in Eq. (2) related to magnetocrystalline cubic anisotropy field and is given in the reference frame related to the crystallographic axes of YIG: [100], [010] and [001] (marked in red in Fig. 2a in the most common form by

(expanded up to second order). \(C_1\) and \(C_2\) are coefficients that will be determined later. Hence, we will refer to the model of taking into account the cubic magnetocrystalline anisotropy in this way as model I.

The cubic magnetocrystalline anisotropy can also be taken into account in an older form10,

This expression, expanded up to first order, has a four-fold symmetry in the (001) plane and two-fold symmetry with respect to the [001] axis, and for \(C_{\parallel } = C_{\perp }\) does show the cubic symmetry in an approximate way only. As previously, numerical values of \(C_{\parallel }\) and \(C_{\perp }\) will be determined later. The model taking into accouny the cubic magnetocrystalline anisotropy in this way will be called the model II.

Finally, the term \(H_U\) in Eq. (2) related to magnetocrystalline uniaxiall field, in the reference frame [100], [010] and [001], takes the form

The prime signs in Eqs. (9), (10) and (11) are intended to remind us that these equations are written not in an experimental frame of reference.

If, in what follows, we refer, for example, to the model IIB, this will mean that for that model \(H_C\) is given by Eq. (10), \(H_D\) — by Eqs. (6) and (8).

Magnetocrystalline and uniaxiall energy in the experimental coordinate system

FMR measurements that will be further analyzed were made for the thin YIG epitaxial film in a plane perpendicular to the [111] axis defined by the YIG crystal structure. The unit vectors in this coordinate system are given by

The unit vectors in the coordinate system related to the YIG crystallographic structure, entering Eq. (5), in Cartesian coordinates, are given by

Consequently, the transformation matrix of basis vectors from the unprimed ([2 -1 -1], [0 -1 1] [1 1 1]) coordinate system ([100], [010], [001]) to the primed ([100], [010], [001]) one has the form

The mutual position of axes in both coordinate systems, i.e., in unprimed (black) and primed (red) is shown in Fig. 2a.

(a) Experimental Cartesian coordinate system (black) and YIG crystallographic coordinate system (red). (b) The term describing the cubic magnetocrystalline anisotropy given by Eq. (9) (for \(C_2=0\)) in both coordinate systems. (c) The term describing the cubic magnetocrystalline anisotropy given by Eq. (10) (for \(C_\parallel = C_\perp\)) in both coordinate systems. (d) The same as (b) seen from above along [111] axis - note the emerging three-fould symmetry in experimental coordinate system.

Therefore, in order to transform \(H_C\) and \(H_U\), given by Eqs. (9), (10), (11), to the experimental coordinate system, primed vectors should be replaced by unprimed ones, in accordance with the Eq. (14). The result of such a transformation for \(H_C^I\) with \(C_2=0\) is shown in Fig. 2b: Fully cubic symmetric \(H_C^I\) in the the [100], [010], [001] axis system (red) is only three-fold symmetric with respect to [111] axis rotation in the experimental coordinate system (black). This symmetry is very clearly visible if we look along the [111] axis, as shown in Figs. 2c and d. As we will see below, the machine learning algorithm will detect this reduction in symmetry, even though the magnetocrystalline energy associated with it is two orders of magnitude lower than the Zeeman and demagnetization energies.

A way to find the parameters on which the free energy depends

Free-energy landscape reconstruction resulting from an FMR experiment, i.e., determining its dependence on \(\theta _H\) and \(\phi _H\) requires identifying unknown parameters in Eq. (2), such as \(C_1\), \(U_1\), \(\mathcal {N}_x\), and others, see Eqs. (6-11). The machine learning (ML) procedure sets the constant Gaussian curvature of the free energy surface, determined by the interplay between the curvatures of the Zeeman term and various fictitious fields, to \(\big ( \frac{\omega }{\gamma } \big )^2\). Subsequently, it selects unknown parameters to which these fields are proportional during training, ensuring that the curvature remains constant for all angles \(\theta _H\) and \(\phi _H\). The following Smit-Beljers (S-B) equation4,5,6,7 connects the Gaussian curvature and the sought coefficients \(C_1\), \(U_1\), \(\mathcal {N}_x\), etc.,

\(\kappa _1\) and \(\kappa _2\) are the principal curvatures of the free energy landscape at a given point and \(\kappa _1\kappa _2\) is the Gaussian curvature at this point.

The magnetic free energy f is reliant on two pairs of angles: \(\theta _H, \phi _H\) and \(\theta , \phi\). The vector \(\textbf{M}\) points towards the lowest energy f, so the following relationships should hold

Furthermore, the second derivatives of f with respect to \(\theta\) and \(\phi\), and thus also \(\kappa _1\) and \(\kappa _2\), should be positive. These conditions enable us to determine \(\theta (\theta _H)\), \(\phi (\phi _H)\), and their inverses, and need to be satisfied in the ML process.

The ML procedure is reminiscent of a reverse process of measurement. It involves altering the anisotropy and demagnetizing fields so that Eq. (15) is satisfied as closely as possible for all measured static resonance fields. The goal is to minimize the deviation from the constant curvature regarding the unknown anisotropy and demagnetizing fields.

Understanding the functional form of free energy is crucial for the machine learning process. It is typically assumed based on the system’s symmetry, which allows us to expand it into basis functions with the same symmetry. However, this expansion is usually limited to low-order terms with systematically decreasing basis functions. In the case under consideration, these functions are, for example, \(n_x^{2}, n_y^{2}, n_z^{2}, n_x^{4}, n_y^{4}, n_z^{4}\), and their products. When examining curvature, it is essential to consider that higher-order basis functions may significantly impact the total curvature of free energy. Refs. 2 and3 provide a detailed description of the procedure.

Analysis of FMR experimental results

The dependencies of the resonance field \(\mathbf {H_r}\) on angles for each model being considered

We will consider three models of the expansion of magnetic free energy: IA, IB, and IIB. Each of these three models represents a different curvature of the free energy surface.

For the models IA and IB, one expands the magnetic free energy of YIG thin film up to the second order for terms with cubic symmetry (i.e., constants \(C_1\) and \(C_2\) are present in Eq. (9) and up to the first order for terms with uniaxial symmetry.

The curvature of free energy spatial distribution, given by Eq. (15), for the model IA, depends thus on four parameters, which we denote collectively by the vector

where, as usuall, \(M_{ef\!f}=2\pi M - U_1\). Similarly, for the model IB

For this model the other two components of the demagnetization tensor, see Eq. (6), are equal: \(\mathcal {N}_x=\mathcal {N}_y=\frac{1}{2}(1-\mathcal {N}_z)\). We also put the constant \(C_2\) equal to 0. For the model IIB the magnetic free energy is described by the following vector:

The angle \(\phi _{H0}\) is present in the Eqs. (17), (18) and (19) because this angle of rotation of the YIG thin film about the [111] axis was not known in the resonance field \(H_r(\theta )\) measurements9.

The numerical values of the components of the \(\textbf{h}_{IA}\) vector were given for the first time in9,

(\(\phi _{H0}\) in radians, the values of fields in kOe). These values were found by fitting the S-B equation written in the plane (01-1), rotated by the angle \(\phi _{H0}\) about the [111] axis, that is, without considering the free energy’s curvature, to all experimental data. The numerical solution of the S-B equation for such a vector \(\textbf{h}_{IA}\), i.e. the dependence of the resonance field \(H_r\) on the angle \(\theta _H\), is shown in comparison to the measured values of \(H_r\), for different frequencies, in Fig. 3. It is clear that for angles \(\theta _H\!>\!0\), the approach leading to the form of \(\textbf{h}_{IA}\) given by Eq. (20) seems to be inappropriate due to some systematic error. This error, visible as a systematic deviation of the calculated curve from measured values for \(\theta _H>0\) in Fig. 3 for all frequencies, indicates that the cubic magnetocrystalline anisotropy with three-fold symmetry about the [111] axis, being the source of this departure, was not taken into account correctly.

Experimental dependence of the resonance field on the polar field angle \(\theta _H\) at frequencies 0.7, 1, 1.6, 2.5, 4, 6, and 8 GHz, represented by squares of different colors. Solid lines of the same colors are the solutions of the S-B equation for the model IA and the vector \(\textbf{h}_{IA}\) found by fitting procedure, as described in9, and given by Eq. (20).

To find out whether not taking into account the curvature of the spatial distribution of free energy is the source of this systematic error we analyzed the same experimental results using models IA, IB and IIB within the method based on machine learning described in2.

We use also the cross-validation leave-one-out technique since the considered dataset are small. This involves dividing the experimental data, consisting of N elements, into two subsets: the training set \(N-1\) elements) and the test set (1 element), in N different ways. We then use the N subsets for training to determine the values of the unknown components of the vector \(\textbf{h}\) by minimizing the error function \(E_{RMS}^{N-1}\), which is the positive square root of the sum of squares of residuals between the model predictions and experimental data. At the same time, we calculate the error function \(E_{RMS}^{1}(\textbf{h})\) for the single left test point. This error function helps us gauge the accuracy of predicting the components of the vector \(\textbf{h}\) for a specific model. Finally, after the N minimizations, we analyze how the averages \(\left<E_{RMS}^{N-1}\right>\) and \(\left<E_{RMS}^{1}\right>\) vary with the model. The smaller the value of \(\left<E_{RMS}^{1}\right>\), the better the model describes the experimental data, indicating a better predictive ability.

First, let us change the curvature of the IA model’s spatial distribution of free energy by adding a term \(U_2 n_z^{4}\) to its expansion. The resulting components of the vector \(\textbf{h}_{IA}\) are given in the Tab. 1, in the line marked “all frequencies, this work” and the numerical solution of the S-B equation for such a vector \(\textbf{h}_{IA}\), i.e., the dependence of the resonance field \(H_r\) on the angle \(\theta _H\), is shown in comparison to the measured values of \(H_r\), in Fig. 4. It is clearly visible that changing the free energy curvature during CV procedures significantly reduced the systematic error observed in Fig. 3, although some error still remains visible in Fig. 4.

Second, to correct this error, we will adjust the curvature of the spatial distribution of demagnetization energy and describe the demagnetization using the ellipsoid defined by Eqs. (6) and (8). This model, known as model IB, will also help us determine the saturation magnetization independently3. Based on this assumption, we obtain the coordinates of the vector \(\textbf{h}_{IB}\) as shown in the first row of Table 2 for the training set of experimental data for all frequencies. Unfortunately, this approach does not resolve the systematic error visible in Fig. 4. Moreover, the plot of \(H_r(\theta )\) is consistent with the one presented in that figure.

Similar findings apply to the IIB model. We have observed that utilizing models which describe the curvature of the magnetic free energy surface differently produces identical results when analyzing a training set containing data for all frequencies. However, the machine learning algorithm yields different coefficients for each model’s magnetic free energy series expansion.

Let us consider a bizarre question: Does the resonance frequency affect the elements of the \(\textbf{h}_{IA}\), \(\textbf{h}_{IB}\), and \(\textbf{h}_{IIB}\) vectors? To answer it, we will perform the ML+CV procedure for the S-B equation separately for each frequency for models IA, IB, and IIB.

Solid lines of different colors represent the solutions of the S-B equation for model IA and the vectors \(\textbf{h}_{IA}\) from subsequent rows of Table 1. These were found by machine learning and cross-validation procedures for each frequency separately, as described in2. Squares of the same colors correspond to the experimental data.

The values of the components of \(\textbf{h}_{IA}\), \(\textbf{h}_{IB}\) and \(\textbf{h}_{IIB}\) vectors obtained for each frequency separately are given in the appropriately marked rows of Tabs. 1, 3 and 3. Functions \(\left<E_{RMS}^{1}({\textbf{h}})\right>\), describing the predictive ability of the models for each frequency separately, are significantly smaller than the corresponding functions calculated for all frequencies. The discrepancy between the experimental data and those predicted by the model for each frequency separately, as shown in Figs. 3 and 4, has disappeared, as shown in Fig. 5.

To better illustrate the reduction in mismatches predicted by the IA model for resonance fields, we present the results for a frequency of 2.5 GHz and anisotropy fields determined by different methods in a single Figure 6. The green curve represents the largest discrepancy and corresponds to the anisotropy fields obtained from the fitting procedure in9. We observe that the gap between the experimental data and IA model predictions decreases when the anisotropy fields are determined using the ML procedure, particularly when the training set includes data from all frequencies, as shown by the blue curve. The smallest discrepancy, which is nearly imperceptible on the scale of the figure, occurs when the training set is limited to data from only one frequency (in this case, 2.5 GHz).

Let us stress that the predicted dependencies \(H_r(\theta _H)\) are indistinguishable on the plot scale for models IA, IB, and IIB. Therefore, we continue to limit ourselves to the IA model if we do not consider demagnetization and IB when we need to find the demagnetization energy. The only exception will be the dependence of the magnetocrystalline anisotropy field on the angle \(\theta _H\), see Fig. 12.

The IA model predictions for the resonance field \(H_r\) as a function of the angle \(\theta _H\) at a frequency of 2.5 GHz after using a learning set that includes data for all frequencies. The experimental results are represented by gray squares. The predictions for anisotropy fields determined in9 are shown as a green line, for while the predictions for the fields listed in the second row of Table 1 are depicted in blue. Additionally, the prediction for same model applied to fields derived from a learning set containing only one frequency 2.5 GHz (the sixth row of the Table 1) is represented by red line. .

When comparing the last columns of Tables 1, 3 and 3, we also observe that models IA, IB, and IIB exhibit similar predictive ability. Thus, there is no requirement to posit that the magnetic free energy of YIG contains magnetocrystalline fields of order higher than two.

We observe that calculating the components of the \(\textbf{h}_{IA}\), \(\textbf{h}_{IB}\), and \(\textbf{h}_{IIB}\) vectors separately for each resonance frequency has a significant impact on the accurate reconstruction of the experimental data. What does it signify, and why is it imperative to comprehend?

To investigate this issue, let us begin by noting that the measured resonance fields \(H_r\) for each frequency are not symmetrical with respect to the angle \(\theta\), meaning that \(H_r(\theta )\ne H_r(-\theta )\). In the free energy expansion (2) in the experimental coordinate system, all terms are symmetric when \(\theta _H\! \rightarrow \! -\theta _H\), except for the term that describes the magnetocrystalline anisotropy, which is visible in Fig. 2d. The lack of this symmetry is due to the appearance of a three-fold symmetry of the magnetocrystalline field, see Eq. (10), in the experimental coordinate system when rotations of the film occur about the [111] axis: the four-fold (cubic) symmetry disappears, and three-fold symmetry emerges.

Numerically calculated equilibrium angle \(\theta\) as a function of field angle \(\theta _H\) for angles \(\phi _{H0}\) and data corresponding to subsequent frequencies from Table 2. The wider blue bar represents the same for data from the row “All frequencies, this work” from this Table. The width of the bar is equal to the error in determining \(\theta\).

Numerically calculated equilibrium angle \(\phi\) as a function of field angle \(\theta _H\) for angles \(\phi _{H0}\) and data corresponding to subsequent frequencies from Table 2. The wide skyblue bar represents the same for data from the row “All frequencies, this work” from this Table. The width of the bar is equal to the error in determining \(\phi\).

To understand this, let us analyze how the equilibrium angles \(\theta\) and \(\phi\) depend on field angles \(\theta _H\) and \(\phi _H\). These angles are found by solving the S-B Eq. (15) numerically, and we will explore how they depend on \(\theta _H\) and \(\phi _H\) for different frequencies. The dependencies \(\theta (\theta _H)\) and \(\phi (\theta _H)\) are illustrated in Figs. 7 and 8. It is worth noting that they are neither symmetric nor antisymmetric. This lack of symmetry in the equilibrium position of the vector \(\textbf{M}\) is due to the presence of the three-fold symmetry of the magnetocrystalline anisotropy. As a result, it leads to a non-symmetrical resonance field \(H_r\) for \(\theta _H\). These observations apply to all three models, but we have presented the graphs for the IB model only.

Let us also note the wide blue bar in Figs. 7 and 8: it represents dependence \(\theta (\theta _H)\) and \(\phi (\theta _H)\) obtained using the ML + CV methods for all frequencies, and its width is equal to the statistical error. We see that \(\theta (\theta _H)\) and \(\phi (\theta _H)\) for small frequencies lie outside the statistical error, so determining these dependencies based on the data for all frequencies is incorrect.

Let us conclude that even slight changes in the curvature of the energy distribution can result in significant alterations in the equilibrium angles. Consequently, this will lead to systematic changes in the predicted resonance field \(H_r(\theta _H)\). These changes have been particularly noticeable in lower frequencies when magnetocrystalline energy became a more substantial part of magnetic free energy.

Magnetic free energy

Having calculated the components of vectors \(\textbf{h}_{IA}\) and \(\textbf{h}_{IB}\), we can determine how the magnetic free energy (in units of saturation magnetization M) for a given resonance frequency depend on the angle \(\theta _H\). All the components of magnetic free energy \(f(\theta _H,\phi _H)\) versus the angle \(\theta _H\) for the model IB, see Eq. (2), are shown in Fig. 9 - for 8 GHz in and Fig. 10 - for 1.6 GHz for the model IB.

Each component of Eq. (2) describe a spatial distribution of magnetic field \(f(\theta _H,\phi _H)\) that varies in space with a specific curvature. The curvature of the Zeeman term depends on the static magnetic field and can be changed during the measurement, while the curvatures associated with the fictitious demagnetizing and cubic anisotropy fields remain constant throughout the measurement.

When performing an FMR experiment, one chooses the Zeman field \((H_r)\) to maintain a constant curvature of the field \(f(\theta _H,\phi _H)\) for a resonant frequency. It follows that the coefficients in the series expansion of \(f(\theta _H,\phi _H)\) may also depend on frequency.

In Figs 9 and 10, the proportions of the individual components of Eq. (2) are shown for the model IB. At 8 GHz, the Zeman term is approximately five times greater than at 1.6 GHz, while the demagnetization term remains the same for both frequencies. Therefore, the relative contribution of the magnetocrystalline term to the total energy increases as the frequency decreases. The same observations apply to the IIB model as well.

Finally, let us focus on a fictitious field corresponding to magnetocrystalline anisotropy. Their dependencies on the angle \(\theta _H\) are depicted in Figs. 11 and 12 for models IA and IIB. The dependencies are much more evident in Figs. 11 and 12 compared to Figs. 9 and 10, where they are nearly invisible. In typical FMR experiments, the magnetocrystalline anisotropy energy is several dozen times smaller than the absolute value of the total free energy. This difference explains why the energy scale in Figs. 11 and 12 is approximately 100 times larger than in Figs. 9 and 10.

Similar to before, the large blue bar represents this dependency, which was determined when the training set included the results of resonance field measurements for all frequencies. The width of the bar equals the statistical error. The colors indicate \(H_c(\theta _H)\) when the training set encompassed the results of measurements for only one frequency. We observe that \(H_c(\theta _H)\) curves for lower frequencies fall outside of the statistical error, indicating that determining these dependencies based on the data for all frequencies is incorrect. This confirms that expanding the free energy in a series with respect to fictitious anisotropy fields should be carried out separately for each frequency.

Summary and conclusions

The paper presents new findings from an analysis of low-frequency FMR experiments using the ML+CV method. We reinterpreted an old FMR experiment9 that focused on measurements of \(H_r\) for YIG thin film in an out-of-plane geometry. We used three different models to describe the spatial distribution of magnetic-free energy. Despite each model depending on different parameters, all three models consistently resulted in the experimentally observed relation \(H_r(\theta )\). It is important to stress that this agreement was found for each resonance frequency separately after applying the ML + CV procedure to each frequency.

This observation led to an important conclusion: Magnetocrystalline cubic anisotropy constants, which are proportional to the magnetocrystalline cubic anisotropy fields, cannot be considered constants. They are parameters in the magnetic free energy expansion only. In addition, through multiple analyses, machine learning algorithms consistently detected frequency-dependent parameters, which led to the proper experimental dependence \(H_r(\theta )\). This significant observation was validated independently for three distinct models, underscoring its relevance in the analysis of resonance experiments.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Farle, M. Ferromagnetic resonance of ultrathin metallic layers. Rep. Progress Phys. 61, 755 (1998).

Tomczak, P. & Puszkarski, H. Ferromagnetic resonance in thin films studied via cross-validation of numerical solutions of the Smit-Beljers equation: Application to (Ga, Mn) As. Phys. Rev. B 98, 144415. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.98.144415 (2018).

Tomczak, P. & Puszkarski, H. Interpretation of ferromagnetic resonance experimental results by cross-validation of solutions of the Smit-Beljers equation. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 507, 166824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmmm.2020.166824 (2020).

Smit, J. & Beljers, H. G. Philips Res. Rep. 10, 113 (1955).

Artman, J. O. Ferromagnetic resonance in metal single crystals. Phys. Rev. 105, 74. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.105.74 (1957).

Baselgia, L. et al. Derivation of the resonance frequency from the free energy of ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 38, 2237. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.38.2237 (1988).

Morrish, A. The Physical Principles of Magnetism ( publisher Wiley-IEEE Press, 2001)

Serga, A. A., Chumak, A. V. & Hillebrands, B. YIG magnonics. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 43, 264002. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/43/26/264002 (2010).

Lee, S. et al. Ferromagnetic resonance of a YIG film in the low frequency regime. J. Appl. Phys. 120, 033905. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4956435 (2016).

Wang, H., Du, C., Hammel, P. C. & Yang, F. Strain-tunable magnetocrystalline anisotropy in epitaxial Y 3 Fe 5 O 12 thin films. Phys. Rev. B 89, 134404. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.89.134404 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Professor Henryk Puszkarski for the critical reading of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Napierała-Batygolska, A., Tomczak, P. Revisiting low-frequency ferromagnetic resonance in yttrium iron garnet thin films. Sci Rep 15, 11277 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91228-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91228-0