Abstract

In a population-based survey, Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection status, associated risk factors and vaccine coverage among the 4006 Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTG) participants of Odisha Tribal Family Health Survey (OTFHS) were assessed using various viral markers. All the HBsAg-positive sera were screened for viral load estimation, envelopment antigen (HBeAg) identification and liver profile parameters. The overall prevalence of HBsAg was 5.73% and the Kutia Khond tribes showed highest prevalence (17.85%; 95% CI:17.41–18.29) of HBsAg. Only 2.7% of children born following the implementation of hepatitis B vaccination were HBsAg positive. Among the children between 0 and 36 months, the vaccination coverage was 91% and mean Anti-HBs titre was 142.56 mIU/ml. Tattooing and piercing were found to be positively associated with high HBsAg positivity. Abnormal liver function (high SGOT and SGPT) occurred more often in HBeAg positive with high viral loads (> 2000 IU/ml). Given the high prevalence of HBV DNA with active viral replication, a strategy for regular monitoring and treatment of these individuals combined with risk factor management and health education in this indigenous population is urgently needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a substantial global health issue, affecting an estimated 254 million people worldwide with chronic infection. The Hepadnavirus targets the liver and poses a serious threat to chronically infected individuals, potentially leading to liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and accounts for of 1.3 million deaths worldwide. Approximately 1.2 million new infections are reported annually among people exposed to either HBV-infected blood or bodily fluids1. HBV is 50–100 times more infectious than HIV. The virus is most commonly transmitted from mother to child during birth and delivery, as well as through contact with blood or other body fluids during sexual contact with an infected partner, unsafe injections or exposure to sharp objects. Children infected before the age of six are more likely to become chronic carriers2.

With a prevalence of 3–4.2% of Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and 40 million HBV carriers, India is classified as an intermediate endemic zone for the Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in the world3. Despite being in the low endemicity region, certain indigenous population have a greater rate of exposure to Hepatitis B infection because of inbreeding depression, inadequate knowledge regarding the spread of the disease, compromised living circumstances, intimate interpersonal contact and specific sociocultural traditions such as tattooing and piercing of various body parts4,5.

The tribal population of Odisha constitutes around 8.6% of the total population of India, with more than 90% lives in rural areas6. Odisha is one of the major diverse states for indigenous populations, with 62 tribal groups and 22.8% of its population belonging to Scheduled Tribes amounting to over 10 million persons7. In India, a particularly vulnerable tribal group (PVTG), previously known as a Primitive tribal group, is a sub-classification within the Scheduled Tribes, representing a section that is more vulnerable than regular Scheduled Tribe. The present study was part of the Odisha Tribal Family Health Survey, which is the first of its kind in the country. It aims to assess the status of HBV infections among the PVTG population, the various risk factors associated with and the hepatitis B vaccination coverage among children (aged 0–5 years).

Methods

Study design and setting

The study was part of a population-based cross-sectional survey with a multistage random sampling design carried out in the state of Odisha, India. There are 30 administrative districts in the state, among which 11 districts (119 sub-district level blocks) are PVTGs-dominated and included in the survey (Fig. 1)6.

Study population

The study population comprised members of the Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group across all age group (0 to 60 years and above) and gender who belonged to one of the notified tribes, were permanent residents of the region and provided written consent were included in the survey. Participants who were ill or unable to provide required information and did not agree to give blood samples were excluded from the study. Survey was carried out for 1 year from June 20226.

Sampling and sample size

The survey employed a multistage sampling design. The primary and secondary sampling units were clusters and households, respectively. The survey population was stratified based on tribes in the first sampling stage6. The sample size was calculated for each tribe separately to enable comparisons. The aggregated sample size calculated for the survey was 40,921, which was collected from 10,230 households spread over 341 clusters across the state. The population of the PVTGs was 4006 and all were included in the study.

Data and sample collection

The participants were informed on the previous day of the actual survey and were made to understand the importance of the study. Information on various socio-demographic, household characteristics, risk factor, vaccine coverage, anthropometric profile were collected using electronic data collection tool in android tablets. The collected data was uploaded online and extracted in excel sheet format. Data was kept securely and safely for its analysis and further course of action. Following data collection, blood samples were collected from the participants for further laboratory analysis. About 5 ml and 2 ml of blood was collected respectively from adults and children by venipuncture by a trained laboratory phlebotomist. Samples were then transferred to the designated laboratory of ICMR-Regional Medical Research Centre, Bhubaneswar for laboratory diagnosis. Anonymity of both sample and data was maintained with minimal access3.

Laboratory investigation

Testing for serological marker

All 4006 serum samples were tested for detection of viral surface markers, including Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg which is a marker of chronic infection) and total antibody to Hepatitis B core antigen (Anti-HBc which is a marker of HBV infection, either cleared or persistent) using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (HBsAg: J.Mitra & Co. Ltd). Antibody to Hepatitis B surface antigen (Anti-HBs which is a marker of protective antibodies) using ARCHITECT i1000SR immunoassay analyzer. All HBsAg positive sera were further tested for the presence of Hepatitis B envelope antigen (HBeAg which is a marker of active viral infection) using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (HBsAg: J.Mitra & Co. Ltd)3.

Molecular testing

HBV DNA (to assess active HBV viral replication) and viral load estimation were performed for all the HBsAg positive serum using Cobas® HBV (Roche Diagnostics India Pvt. Ltd.) with a specificity of 100%3.

Biochemical testing

The positive HBsAg sera were further tested for the different biochemical parameters like SGOT, SGPT, ALP, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, and albumin to check the liver function test using automated biochemistry analyzer EM-360 (ERBA Diagnostics Mannheim GmbH) and reagents provided by Transasia Biochemical Ltd8.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data were calculated as per the frequency and proportion of the variables. Weighted prevalence of Hepatitis B was calculated in accordance with the socio-demographic distribution and risk factors. Univariate and weighted multivariate regression analysis were adjusted for age, gender, wealth index and sample weight of the findings based on seromarker positivity. Statistical analysis was carried out in STATA v16.0.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of ICMR-Regional Medical Research Centre, Bhubaneswar (reference no: ICMR-RMRC/IHEC-2022/115; dated: 02/05/2022) and have followed the National Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical and Health Research Involving Human Participants by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR). The study also followed the ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects of the Declaration of Helsinki adopted by World Medical Association, 1964 which were last revised in October 2013. No documented assent was obtained for children below 7 years of age. For children between 7 and 12 years, verbal/oral assent was obtained in the presence of the parents/legally acceptable authorized representative (LAR) and was recorded. For children between 12 and 18 years, written assent were obtained, which was signed by the parents/LAR.

Results

The mean age of the study participants was 32.3 years ranging between 1 year and 93 years of age. There were 1786 (44.6%) males and 2220 (55.4%) females in the study population. Majority of the participants (69.8%) belonged to the age group of > 20 years followed by 10–19 years (16.5%), and < 10 years (13.7%). All serum samples collected from 4006 PVTG individuals were tested for the serological markers HBsAg, Anti-HBs, and Anti-HBc. Only 11 PVTGs were included in the analysis, as we could collect only 2 samples from the Birhor and Saora tribes. HBsAg was detected in 170 of the 4006 individuals (4.24%; 95% CI: 5.67–5.79) individuals (Table 1). The weighted HBsAg positivity was highest (6.56%; 95% CI: 6.49–6.63) in > 20 years age groups and among males (7.99%: 95% CI: 7.90–8.09) participants of the PVTGs of the state. Highest prevalence (17.85%; 95% CI:17.41–18.29) of HBsAg was observed among the Kutia Khond tribe. The chronic HBV infection was detected as 2.79% (95% CI: 2.22–3.26).

The wealth index has been calculated for the study participants and has been categorized into lower, lower-middle, middle, middle-higher and higher income groups. Among the HBsAg positive participants, 77 (45.29%) belonged to lower and 44 (25.88%) belonged to lower-middle wealth income groups. Around 101 (59.41%) out of 170 HBsAg positive participants were illiterate and 75 (44.11%) were from agricultural background.

The highest HBsAg (32.39%) positivity was observed in the 10–19 age group of Kutia Khond (95% CI: 30.66–34.16). Males from the Kutia Khond (25.28%, 95% CI: 24.53–26.04) and Dongria Khond (12.36%, 95% CI: 12.14–12.58) tribes showed remarkably higher HBsAg positivity compared to females. Other tribes, such as Bondo Poraja, Juang and Paudi Bhuyan also reflected this trend, where males consistently exhibited higher rates of HBsAg positivity compared to females. The HBsAg positivity among the pregnant women was 3.01% (95% CI: 2.67–3.40) and was observed to be quite high among the pregnant women belonging to the Juang Tribe.

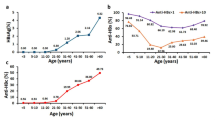

The overall exposure to HBV infection was 42.73% (95% CI: 41.20-44.28), indicating that 1712 individual (out of 4006) were positive for any of the three markers of HBV infection. The highest exposure rate (71.20%, 95% CI: 68.98–73.32) was observed among the adult participants (age 20 and above) who were positive for either HBsAg, or anti-HBs or anti-HBc. Anti-HBc alone positivity was found among 7.34% (95% CI: 6.56–8.20) of individual whereas protective level of Hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs ≥ 10 mIU/ml) was present among 41.14% of individual (95% CI: 39.61–42.68).

All the 170 HBsAg positive individuals were also tested for Hepatitis B envelope antigen (HBeAg) and HBV DNA. HBV DNA was detected among 61 (35.9%) of 170 HBsAg positive samples of which 26 (15.3%) had viral load above 2000 IU/ml. Eleven (6.4%) were HBeAg positive indicating active replication of the virus. All the HBeAg positive participants had HBV DNA viral load above 2000 IU/ml. More than 15% (15.3%) individual were found to carry HBV DNA > 2000 IU/ml with active or inactive HBeAg and a significant number (73.1%) were in the age group of more than 20 years with mean age of 43.3 years (Table 2).

About 2.7% (21 out of 766) of the children born after the introduction of Hep B vaccine (2011-12) were positive for HBsAg. Among these none had protective level of antibody. Out of these 21 participants, 6 participants showed presence of HBV viral load of > 2000 IU/ml and three showed active replication of the virus.

Five individuals were found to be positive with concurrent presence of both HBsAg and Anti-HBs titre of > 10 mIU/ml. Of them only a 27 years female was vaccinated and had Anti-HBs titre 26 mIU/ml with presence of Anti-HBc antibody and HBV DNA.

The vaccination coverage among the children aged 0–36 months was 91% and 67.6% had a protective level of antibody. The mean Anti-HBs titre was 142.56 mIU/ml. About 37.5% of children born after the introduction (2012) of HB vaccine have protective level of Anti-HBs. The Anti-HBs titre was found to decrease with increasing age among children aged 0–60 months (Fig. 2).

Table 2 explains various risk factors and their association with Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positivity in two age groups (10–19 years individual and individual aged 20 years and above) across both genders. Tattooing was found to be associated with increased HBsAg positivity in both age groups, although the strength of association varied. In the age group above 10–19 years, individuals with tattoos showed a positivity rate of 4.76%, with an AOR of 2.46 (Table 3). Among males, piercing was associated with a notably higher HBsAg positivity (11.38%) compared to females (2.82%) with higher risk among male (AOR of 1.25). The AOR of 1.74 and 2.44 among both males and females suggested a higher risk among alcohol consumers, particularly among those aged over 20 years. Hepatitis B vaccination was found to impact significantly HBsAg positivity rates across various age groups. Individuals who have received the vaccine show lower HBsAg positivity compared to those who have not been vaccinated (AOR- 1.23). For the age group of 10–19 years, vaccinated individuals have a positivity rate of 4.47%, compared to 3.46% in the unvaccinated group. In the age group of 10–19 years, the protective effect of vaccination is evident but moderate, with an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) of 0.89 indicating reduced risk. In the older age category (more than 20 years), the difference is more pronounced. Vaccinated individuals have a significantly lower HBsAg positivity rate of 2.55% compared to 3.88% in the unvaccinated group of more than 20 years. This disparity underscores the vaccine’s effectiveness in reducing HBsAg positivity, with an AOR of 1.60 for the unvaccinated group suggesting a notable increase in risk. The practice of contraception was associated with varied HBsAg positivity rates. The adjusted odds ratios (AOR) suggest a highly increased risk for contraception non-users (AOR: 2.29) compared to users. Those who were hospitalized showed a significantly higher positivity rate (6.66% for 10–19 years and 8.46% for over 20 years) compared to non-hospitalized individuals, with AOR values of 3.09. Sharing razors also elevated the risk, with an AOR of 3.59 among those who shared razors.

Among those negative for HBsAg, Anti-HBs, and Anti-HBc (n = 3836), the majority exhibited normal liver function, with 73.80% showing normal SGOT, 99.06% normal SGPT and 88.06% normal ALB levels. In HBeAg positive individuals with high viral loads (> 2000 IU/ml), abnormal liver function was more frequent, with elevated SGOT in 46.67% and SGPT in 13.33% of cases. Those who were HBeAg-negative with low viral loads (< 2000 IU/ml) had mostly normal liver tests, including 97.14% with normal SGPT and 100% with normal ALP and BID levels. Higher viral loads were associated with more significant liver function abnormalities, particularly in SGOT and SGPT levels, suggesting that liver health worsens as viral activity increases in individuals infected with Hepatitis B (Table 2).

Discussion

The present study is a part of Odisha Tribal Family Heath Survey (OTFHS) and for the first time, reports the status of Hepatitis B infection among all the PVTGs residing in eleven districts of Odisha. The overall weighted HBsAg seropositivity in the present study was found to be 5.73% (95% CI:5.67–5.79) and was higher than the findings of National seroprevalence of HBsAg (0.95%) observed by MOHFW in 2021 and also higher than the previously reported rates among the PVTGs of the state9,10,11,12,13. India is ranked in the intermediate group for chronic HBV (CHB) and about 50 million people are carriers of CHB infection in India, with a mortality of 0.115 million due to CHB and its complications14,15.

This study is the first of its kind to assess the HBV infection status, associated risk factors and HB vaccination coverage among the PVTGs residing in the eastern state of Odisha. The study reports for the first time the prevalence of HBsAg among the Dongria Kondh, Chuktia Bhunjia, Bondo Poraja and Didayi tribe residing in southern districts of the state. Similar to our previous report3, Kutia Khond showed the highest prevalence of HBsAg across all age group and gender by using the sample weight. The HBsAg seropositivity was higher among the 10–19 years age group.

Hepatitis B vaccine was introduced in the Universal Immunization Programme during 2011–2012 (phase-II) in seven states of India including Odisha and the coverage in India increased from 62.8% in 2015–2016 to 86% in 202016,17,18. Hepatitis B vaccination has been associated with substantial reductions in the incidence of acute and chronic Hepatitis B infections/carriage, which will ultimately result in significant reductions in the incidence of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma19. In the present study, the vaccination coverage among the children aged 0–36 months was documented as 91% and 67.6% had a protective level of antibody. No significant breakthrough in the treatment of CHB is achieved till date, hence, preventive strategies such as vaccination are extremely important to control the infection and consequent disease burden among the people with chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma. The study documented that about 2.7% of the children born after the introduction of Hep B vaccine (2011-12) were positive for HBsAg and who did not have a protective level of antibody. About 36% of children (0–12 years) born after the introduction of HB vaccine did not have a protective level of anti-HBs, indicating the need to improve the coverage of three dose of HB vaccine in India. The WHO has established goals for elimination of viral Hepatitis as a public health threat by 2030, including elimination of MTCT of HBV, which requires an HBsAg prevalence of no more than 0.1% among children and at least 90% coverage with HepB-BD and HepB320,21. With the National Viral Hepatitis Control Programme (NVHCP) being rolled out in India with a target to increase Hepatitis B birth-dose vaccination to > 90%, the present study urges for a need for more intense coverage of the vaccination and further follow up for Antibody development and persistence among these community17.

Tattooing, alcohol consumption, smoking, HB vaccination, use of contraceptive, history of hospitalization and sharing of razor were found to be significant in multivariate analysis of risk factors for HBV infection. Previously personal hygiene, history of hospitalization, use of contraception, immunization and gender have been reported to be significantly associated with HBV infection22,23,24,25.

The study documented that higher viral loads were associated with more pronounced liver function abnormalities, especially in elevated SGOT and SGPT levels. Previous studies have documented a strong correlation between viral load and liver damage in patients with chronic hepatitis26. It has been established that HBV viral load can remain stable over time until HBeAg sero-conversion or a hepatitis flare occurs27. Therefore, it has been hypothesized that a high HBV viral load could be associated with the development of HBV-related liver disease28.

Among the PVTG participants, 15.3% individual were found to carry HBV DNA viral load of > 2000 IU/ml with active or inactive HBeAg and a significant number (73.1%) were in the age group of more than 20 years with mean age of 43.3 years. Recent studies conducted in large Asian cohorts indicate that HBV-DNA levels strongly predict development of HBV-related cirrhosis and HCC29,30.

This study provides valuable insights into hepatitis B prevalence and risk factors among Odisha’s particularly vulnerable tribal groups (PVTGs), yet it faces several limitations. One major limitation is the study’s sampling constraints as data was collected from only a subset of PVTGs in the region, with notably low representation from the Birhor and Saora tribes, potentially impacting the generalizability of findings across all Odisha tribes. As the study is cross-sectional in nature, it limits the understanding of temporal progression of hepatitis B infection, vaccination efficacy over time and changes in antibody levels in individuals, especially among children born after the vaccine’s introduction. Lastly, the study’s findings may have been influenced by potential recall bias or self-report inaccuracies in areas like vaccination history, hospitalization, or behaviours related to personal hygiene practices.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this is the first study to examine in detail the status of hepatitis B infection, risk factors and vaccine coverage among the Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups residing in the state. The HBsAg prevalence among PVTGs estimated in our study was higher than the national seroprevalence of Hepatitis B. As a significant number of individuals are harboring HBV DNA with active viral replication, an intervention strategy needs to be developed for regular monitoring and treatment of the infected individuals, management of risk factors and promotion health awareness among this population of the country. The findings call for a statewide survey of Hepatitis B infection, associated risk factors, coverage and impact of the Hep B vaccination programme in Odisha after 2010-11 with special reference to these indigenous and tribal population of the state.

Data availability

Raw data will be available on request to the corresponding author.

References

World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, care and treatment for people with chronic hepatitis B infection: WHO. (2024). Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/376353/9789240090903-eng.pdf?sequence=1 [accessed 18 May 2024].

Inoue, T., & Tanaka, Y. [Hepatitis, B. Virus infection: current management and prevention]. Rinsho Byori. 64 (7), 771–779 (2016).

Bhattacharya, H. et al. Hepatitis B virus infection among the tribal and particularly vulnerable tribal population from an Eastern state of India: findings from the serosurvey in seven tribal dominated districts, 2021–2022. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1039696 (2023).

Murhekar, M. V., Murhekar, K. M. & Sehgal, S. C. Epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection among the tribes of Andaman and nicobar Islands, India. Trans. R Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 102 (8), 729–734 (2008).

Bhattacharya, H., Bhattacharya, D., Ghosal, S. R., Roy, S. & Sugunan, A. P. Status of hepatitis B infection - a decade after hepatitis B vaccination of susceptible nicobarese, an Indigenous tribe of Andaman & nicobar (A&N) Islands with high hepatitis B endemicity. Indian J. Med. Res. 141 (5), 653–661. https://doi.org/10.4103/0971-5916.159573 (2015).

Kshatri, J. S. et al. Odisha tribal family health survey: methods, tools, and protocols for a comprehensive health assessment survey. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1157241 (2023).

List of Communities. ST & & Development, S. C. Accessed November 30, Minorities & Backward Classes Welfare Department. (2022). Available at: https://stsc.odisha.gov.in/about-us/list-ofcommunities

Aktug Demir, N. et al. Evaluation of the relation between hepatic fibrosis and basic laboratory parameters in patients with chronic hepatitis B fibrosis and basic laboratory parameters. Hepat. Mon. 14 (4), e16975 (2014).

National Program for Surveillance of Viral Hepatitis. Factsheet on Seroprevalence of Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C. National Centre for Disease Control. (2021). Available from: https://nvhcp.mohfw.gov.in/common_libs/Approved%20factsheet_4_10_2021.pdf [accessed 09 June 2024].

Murhekar, M. V. et al. Hepatitis-B virus infection in India: findings from a nationally representative serosurvey, 2017-18. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 100, 455–460 (2020).

Dwibedi, B. et al. Molecular epidemiology of hepatitis B virus in primitive tribes of Odisha, Eastern India. Pathog Glob Health. 108 (8), 362–368 (2014).

Sahoo, P. K., Nanda, G., Sinha, A. & Pati, S. Sero-prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection among tribal under-five children in aspirational Nabarangpur district of Odisha, India. Clin. Epidemiol. Global Health. 23, 101399 (2023).

Shadaker, S. et al. Hepatitis B prevalence and risk factors in Punjab, India: A Population-Based serosurvey. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 12 (5), 1310–1319 (2022).

Ray, G. Current scenario of hepatitis B and its treatment in India. J. Clin. Transl Hepatol. 5, 277e296. https://doi.org/10.14218/JCTH.2017.00024 (2017).

Kumar, D. et al. Hepatitis B vaccination in Indian children: seroprotection and age-related change in antibody titres. Med. J. Armed Forces India. 77 (2), 200–204 (2021).

Lahariya, C., Subramanya, B. P. & Sosler, S. An assessment of hepatitis B vaccine introduction in India: lessons for roll out and scale up of new vaccines in immunization programs. Indian J. Public. Health. 57, 8–14 (2013).

Government of India: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. National viral hepatitis control program operational guidelines. ; 68. (2018). Available from: https://nvhcp.mohfw.gov.in/common_libs/Operational_Guidelines.pdf [accessed 21 July 2024].

Parija, P. P. Hepatitis B vaccine birth dose in India: time to reconsider. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 16 (1), 158–160 (2020).

World Health Organization (WHO). World Hepatitis Day 2013 - This is hepatitis. Know it. Confront it: WHO. (2013). Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/events/detail/2013/07/28/default-calendar/world-hepatitis-day-2013 [accessed 18 August 2024].

World Health Organization (WHO). Global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis 2016–2021. Geneva: WHO. (2016). Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HIV-2016.06 [accessed 12 September 2024].

World Health Organization (WHO). Global guidance on criteria and processes for validation: elimination of motherto-child transmission of HIV, syphilis and hepatitis B virus. Geneva: WHO. (2021). Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240039360 [accessed 30 September 2024].

Athalye, S. et al. Exploring risk factors and transmission dynamics of hepatitis B infection among Indian families: implications and perspective. J. Infect. Public. Health. 16 (7), 1109–1114 (2023).

Murhekar, M. V., Murhekar, K. M., Arankalle, V. A. & Sehgal, S. C. Epidemiology of hepatitis B infection among the nicobarese–a Mongoloid tribe of the Andaman and nicobar Islands, India. Epidemiol. Infect. 128 (3), 465–471 (2002).

Khetsuriani, N. et al. Toward reaching hepatitis B goals: hepatitis B epidemiology and the impact of two decades of vaccination, Georgia, 2021. Euro. Surveill. 28 (30), 2200837 (2023).

Li, D. et al. The impact of hepatitis B knowledge and stigma on screening in Canadian Chinese persons. Can. J. Gastroenterol. 26 (9), 597–602 (2012).

Biazar, T. et al. Relationship between hepatitis B DNA viral load in the liver and its histology in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Casp. J. Intern. Med. 6 (4), 209–212 (2015).

Wu, C. F. et al. Long-term tracking of hepatitis B viral load and the relationship with risk for hepatocellular carcinoma in men. Carcinogenesis 29, 106–112 (2008).

Harkisoen, S., Arends, J. E., van Erpecum, K. J., van den Hoek, A. & Hoepelman, A. I. Hepatitis B viral load and risk of HBV-related liver disease: from East to West? Ann. Hepatol. 11 (2), 164–171 (2012).

Chen, C. J. et al. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma across a biological gradient of serum hepatitis B virus DNA level. JAMA 295, 65–73 (2006).

Mendy, M. E. et al. Hepatitis B viral load and risk for liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in the Gambia, West Africa. J. Viral Hepat. 17 (2), 115–122 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge all the participants for voluntarily participating in this study and for sharing valuable information and experiences. We are also thankful to the Indian Council of Medical Research, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Govt. of India and SCSRTI Dept. Govt. of Odisha for providing financial support for this study.

Funding

This study is being funded by Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Research and Training Institute, Government of Odisha (Grant no: 1399/R-01/21). The funders have no influence on study methods, analysis, interpretation, or publication of results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SP, DB and JSK: conceived the study; HB, DB and MP: undertook analysis, interpretation of the results and drafted manuscript; AS, AP, UKR, RP and KAK: involved in data acquisition; HB, DB and MP: critical review of manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bhattacharya, H., Pattnaik, M., Swain, A. et al. Assessing Hepatitis B virus infection, risk factors and immunization among particularly vulnerable tribal groups in Eastern India. Sci Rep 15, 8388 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91486-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91486-y