Abstract

The unfolded protein response (UPR) plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis and progression of acute myeloid leukemia (AML). This study aims to investigate the prognostic value of UPR-related genes (URGs) and establish a UPR-related gene signature (URGsig) to enhance prognosis prediction and guide therapeutic decision-making in AML. Gene expression profiles of AML patients were obtained from the GDC and GEO databases. Cox regression and LASSO regression analyses were applied to identify key genes for the construction of URGsig. Comprehensive bioinformatics analyses were conducted to elucidate the biological and clinical implications of URGsig. A nomogram integrating URGs and clinical prognostic features was developed to predict survival probability for AML patients. Additionally, the differential expression of core genes within the URGsig was validated in clinical samples. Notably, two distinct UPR-related subtypes were identified, and they displayed significant heterogeneity in clinical outcomes and tumor microenvironment (TME). The URGsig, comprising six URGs, showed a strong correlation with survival outcomes and exhibited robust predictive capabilities. Importantly, patients categorized into the high-risk subgroup based on URGsig were predicted to show lower chemosensitivity but a better response to immunotherapy. The nomogram performed well in prognosis prediction, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.912 for 5-year overall survival. In summary, our findings highlight the URGsig as a promising prognostic biomarker and provide novel insights into the mechanism by which UPR influences the immune landscape of AML. This paradigm may lay a foundation for the development of personalized treatment strategies for AML patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) represents a highly aggressive hematopoietic malignancy characterized by the uncontrolled expansion of undifferentiated and immature myeloid cells1. Current classification and risk stratification schemes for AML predominantly depend on genetic and clinical parameters2,3. However, a subset of AML patients fails to achieve satisfactory outcomes under existing stratification frameworks, calling for more refined and personalized risk assessment models to optimize therapeutic strategies and clinical managements. Growing evidence has substantiated the predictive value of novel molecular biomarkers in the outcomes of AML patients4,5,6. Thus, there is an urgent necessity for more comprehensive prognostic models that integrate these molecular markers with conventional predictors, aiming to facilitate more accurate prognosis prediction and provide more effective treatment guidance for AML patients.

Cell proliferation and growth are heavily dependent on increased protein synthesis, which often leads to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) overload, the accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins within this cellular compartment, and ultimately ER stress. Under ER stress, protein homeostasis is finely regulated by a mechanism known as the unfolded protein response (UPR), which involves the activation of signaling pathways mediated by three stress sensor proteins, namely PERK, IRE1α, and ATF67. Notably, IRE1α signaling is the most conserved UPR axis in eukaryotic cells. Activated IRE1α catalyzes the unconventional splicing of XBP1 mRNA, generating a potent transcriptional activator that drives the expression of UPR target genes7. Under steady state, IRE1α-XBP1 signaling repress the pro-leukemogenic transcriptome and safeguard against the onset of myeloid leukemogesis in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs)8. Proliferating HSPCs utilize the activated IRE1α-XBP1 signaling pathway to cope with ER stress and sustain their survival9.

Leukemic stem cells emerge from accumulation of genetic alteration in HSPCs and these cells often exploit UPR to fuel leukemogenesis and disease progression. The IRE1α-XBP1 pathway has been demonstrated to be significantly activated in both cell lines and primary patient samples10,11,12. Pharmacological inhibition of XBP1 has been shown to induce AML cell apoptosis and significantly extends disease latency10,11. UPR activation also trigger calreticulin expression, which subsequently suppresses CEBPA, a critical transcription factor governing myeloid differentiation13. Moreover, numerous UPR-regulating molecules have been identified as being associated with treatment response and clinical outcomes in AML, including VCP14, DDIT315, DNAJC1016, and HMGCS117. Beyond its cell-intrinsic effects, the UPR pathway also modulates immune cells function within the tumor microenvironment by impairing antigen-presentation cell function18, activating myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)19, and promoting T cell exhaustion19.

Recently, a growing number of studies have uncovered the prognostic utility of UPR-related gene signature (URGsig) in various solid cancers. These findings underscore the potential clinical applicability of URGsig in AML20,21,22. However, the specific roles of UPR-related genes (URGs) in AML prognosis prediction, immune regulation and drug resistance remain largely elusive. In this study, we identified and validated a robust URGsig that efficiently predicts prognosis in AML patients. The URGsig enabled stratification of patients into two distinct high- and low-risk subgroups, which exhibited significant differences in survival outcomes, tumor immune landscape, immunotherapy responsiveness, and chemotherapy sensitivity profiles. To enhance clinical applicability, we also constructed a prognostic nomogram by integrating the URGsig with established clinical prognostic factors, providing a reliable tool for individualized survival prediction in AML patients.

Methods

Data acquisition and analysis of expression profile of URGs

Gene expression profiles and corresponding clinical data for 151 AML patients in were obtained from the The Cancer Genome Atlas Acute Myeloid Leukemia (TCGA-LAML) cohort through the Genomic Data Commons (GDC) portal website (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). After quality control and data filtering, 132 patients with complete RNA sequencing data and comprehensive clinical annotations were retained as the training cohort for subsequent analyses. Additionally, somatic gene mutation and copy number variation data were retrieved from the same GDC repository to perform comprehensive molecular characterization of the cohort.

Five independent cohorts (GSE9476, GSE71014, GSE12417, GSE37642, GSE66525) were acquired from the Gene Expression Onmibus (GEO) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and one independent cohort (Beat AML 1.0) was obtained from the GDC portal website. For GEO cohorts, we directly downloaded the already standard matrix files. RNA-sequencing profiles of the TCGA-LAML and Beat AML 1.0 were transformed into transcripts per million (TPM) for subsequent log2 transformation. The overall survival (OS) was defined as the duration from initial diagnosis to death from any cause or until the censoring date of the last follow-up. The Table S1 shows sample information for all cohorts.

All the transcriptional profiles analyzed in this study were derived from bone marrow samples. The GSE9476 dataset, comprising 10 normal and 26 AML samples, was utilized to compare URGs expression patterns between healthy individuals and AML patients. The Beat AML dataset was employed to examine differential URGs expression between complete-remission (n = 115) and refractory (n = 47) patient groups. The prognostic performance and generalizability of the URGsig-based prognostic model were validated using three independent AML cohorts (GSE71014, GSE12417, and GSE37642). Additionally, the GSE66525 dataset, containing 11 matched diagnosis-relapse sample pairs, was analyzed to investigate the association between URGs-based risk scores and disease relapse.

Identification of prognostic URGs and URGs-related molecular subtypes

The URGs were accessed from GeneCards website (https://www.genecards.org/) using key words “unfolded protein response”. The genes with relevance scores more than 5 were selected for subsequent analysis. Then, univariate Cox regression analysis was conducted to identify genes associated with prognosis, and genes with p value less than 0.01 were identified as candidate URGs. Finally, consensus clustering was performed to identify UPR-related molecular subtypes using the R package “ConsensusClusterPlus”. In order to obtain reliable and stable clustering results, iteration was set as 1000 times. t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) was also used to validate the classification using R package “Rtsne”.

Construction of a prognostic UPR-related gene signature

The AML samples in TCGA-LAML dataset were chosen as the training cohort. The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) Cox regression analysis was performed to select significantly prognostic URGs using the “glmnet” R package. Then, multivariate Cox regression analysis was carried out to screen independently prognosis-associated genes to further generate the URGsig. Subsequently, each AML patient was assigned the risk score using the expression level and regression coefficient of the finally selected URGsig genes based on the formula:

Depending on the calculated median risk scores, these AML patients were categorized into low- and high-risk subgroups. Scatter plots and risk score distribution plots were generated to describe sample characteristics, and heatmaps were drew to visualize gene expression profiles. The R package “timeROC” was used to plot the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for assessment of the predictive capability of the URGsig.

Subgroup analysis

The patients in TCGA-LAML cohort were grouped according to clinical features, including age (< 60 years and ≥ 60 years), sex (male and female), race (white and other), white blood cell count (< 30 × 109 and ≥ 30 × 109), cytogenetic risk grade (good, intermediate and poor), gene mutation burden (low and high), and FLT3, DNMT3A, NPM1, TP53, IDH1/2 mutation status to further evaluate prognostic differences between high- and low-risk subgroups.

Functional enrichment analyses and genomic alterations analyses

The R package “DESeq2” 23 was used to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between low- and high-risk subgroups, with filtering thresholds as follows: (1) |log2FC|≥ 1; (2) P < 0.05. Then, Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomics (KEGG)24,25,26 enrichment analysis was performed by utilizing the “clusterProfiler” R package27. Also, GSEA analysis was employed to investigate the differentially enriched GO and KEGG pathways between low- and high-risk subgroups27. The differences of somatic mutation between the two subgroups were investigated using “maftools” package28, and the top 20 frequently mutated genes were visualized by the heatmap. For CNV data analysis, the genomic identification (GISTIC) algorithm29 was employed to estimate CNVs at each core gene of URGsig. The protein–protein interaction was evaluated using STRING tools (https://cn.string-db.org/)30.

Immune microenvironment analysis

The CIBERSORT algorithm was conducted to evaluate the proportion of immune cells in AML samples31. The ESTIMATE algorithm was adopted to calculate the immune, stromal and ESTIMATE scores of each AML samples32. The scores of immune related pathways were estimated by principal component analysis (PCA) and showed by the heatmap. All above calculations were performed using the R package “IOBR” 33.

Prediction of chemotherapy sensitivity and immunotherapy response

The Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC, https://www.cancerrxgene.org/) database provides comprehensive information on drug sensitivity in AML cells and matched transcriptional data of molecular markers of drug response. Using the R package “pRRophetic”, we predicted drug sensitivity for each patient cluster based on the expression profiles of drug-response-related markers, with the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) serving as the quantitative measure of therapeutic response34. Lower IC50 values indicate greater drug sensitivity. For immunotherapy response prediction, we implemented Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion (TIDE) tool (http://tide.dfci.harvard.edu/) to estimate the TIDE score of each AML sample35. Moreover, the Submap algorithm (https://cloud.genepattern.org/gp) was employed to predict the response of different risk subgroups to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy with anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA436.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from bone marrow samples using the TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). cDNA was synthesized from the total RNA using BeyoRT™ II First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit. RT-qPCR was conducted using BeyoFast™ SYBR Green One-Step qRT-PCR Kit on the StepOnePlus™ instrument. β-actin was used as experimental reference. Each sample was measured three times. All PCR primers used in this study are listed in Table S2.

Ethical approval

The collection of clinical specimens was approved by the Ethics Committee of Wuhan Children’s Hospital. Informed consents were signed for all patients. All methods were performed according to the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Statistical analysis

Survival curves were depicted using Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank test was used to compare the differences of survival outcomes. The Wilcoxon test was adopted to compare the differences of gene expression levels between the two groups. The relationships between parameters were estimated using Spearman’s correlation test. Chi-square test was used to compare the differences of gene mutation profiles between the two risk subgroups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant unless stated otherwise (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001). All statistical analyses were conducted with the use of R software, version 4.4.

Results

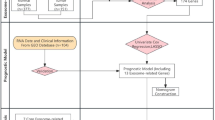

The gene expression and genomic alteration landscape of URGs in AML

This study was conducted according to the systematic workflow as shown in Fig. S1. A total of 163 URGs were obtained from the GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/) website (Table S3). Then, 22 significantly prognostic URGs were identified through univariate Cox regression (P < 0.01) (Table S4). The differential analysis revealed distinct expression patterns: CALR, CREB3, DNAJC10 and VCP were up-regulated in AML samples compared to normal controls, while DNAJB11, ELANE, SOD1 and TRAP1 were down-regulated (Fig. 1A). Additionally, CALR, DNAJC10 and VCP were more highly expressed in complete-remission samples than in refractory cases, whereas DNAJB11, MBTPS1 and SOD1 showed the reverse expression pattern (Fig. 1B). The protein–protein interaction network analysis using STRING identified VCP, SOD1, CALR and DNAJC10 as hub genes among 22 prognostic URGs (Fig. 1C). Gene mutation analysis using R package “maftools” revealed a relatively low mutation frequency of URGs across the cohort (Fig. S2A). Besides, copy number variation analysis using GISTIC algorithm identified recurrent genomic amplification in several URGs, particularly CALR, CHCHD10, ELANE, and SOD1 (Fig. S2B).

Gene expression and protein–protein interaction analysis of selected 22 URGs. (A) Differential expression profiles of URGs between AML samples (n = 26) and healthy donors (n = 10) in GSE9746 cohort. (B) Differential expression profiles of URGs between complete-remission patients (n = 115) and refractory patients (n = 47) in Beat AML cohort. (C) The protein–protein interaction network of these 22 URGs. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Identification of URGs-related molecular subtypes

To identify distinct molecular subtypes associated with URGs expression patterns, we performed consensus clustering analysis on AML patients in the TCGA-LAML cohort. The optimal clustering (k = 2) revealed two robust URGs-related subtypes (Fig. 2A), with clear separation confirmed by t-SNE visualization and differential gene expression patterns illustrated in the heatmap (Fig. 2B, C). Survival analysis demonstrated significantly poorer outcomes in Cluster B compared to Cluster A (Fig. 2D). We subsequently explored TME of two subtypes using ESTIMATEScore, ImmuneScore and StromalScore algorithm. As shown in Fig. 2E, cluster B displayed higher stromal scores, immune scores, and microenvironment scores than cluster A (Fig. 2E), with particular enrichment of B cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, endothelial cells, macrophages and NK cells (Fig. 2F). Further, analysis of immune checkpoint molecules showed elevated expression of PDCD1, CTLA4, and LAG3 in cluster B (Fig. 2G). Notably, the increased immune escape potential observed in Cluster B was also evidenced by lower TIDE scores in Cluster B (Fig. 2H), indicating a good response to immune-check-point targeted therapy for this subtype. These findings collectively imply a strong association between URGs-related molecular subtypes and immunotherapy responsiveness in AML.

Identification of URGs-related molecular subtypes and differential analysis of immune microenvironment between subtypes. (A) Consensus clustering and (B) t-SNE analysis showing that AML patients were classified into two molecular subtypes named cluster A (n = 77) and cluster B (n = 55), respectively. (C) Heatmap showing the differential expression profiles of 22 URGs between the two molecular subtypes. (D) Survival outcomes, (E) TME scores, (F) immune cell infiltrations, (G) expression levels of immune check point genes and (H) TIDE scores were compared between the two molecular subtypes. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

Construction and validation of the UPR-related gene signature in AML

To systematically evaluate the prognostic impact of URGs in AML, we first employed LASSO Cox regression analysis to identify 12 clinically relevant URGs from TCGA-LAML cohort (Fig. 3A, B). Subsequent multivariate Cox regression analysis refined this selection to six statistically significant prognostic genes (DNAJC10, DNAJB11, ANXA11, MBTPS1, SOD1 and VCP), which were used to construct the URGsig (Fig. 3C). Using the median risk score as the cutoff, we stratified patients into high- and low-risk subgroups (Fig. 3D). The high-risk subgroup showed significantly higher mortality rates during follow-up compared to low-risk subgroup (Fig. 3E), with differential expression pattern of key signature genes, particularly downregulation of DNAJB11 and MBTPS1 in high-risk patients (Fig. 3F).

Construction and validation of the URGsig-risk-score model. (A–B) LASSO coefficient profiles and the tuning parameter (λ) were calculated, and the best-fit profile was used to select URGsig. (C) Forest plot showing the hazard ratio of URGsig in TCGA-LAML cohort. (D–E) Survival time distribution and survival status between low- and high-risk subtypes. (F) Heatmap showing the differential expression profiles of URGsig between low- and high-risk subtype. (G–J) Survival analysis between low- and high-risk subtype in (G) TCGA-LAML, (H) GSE71014, (I) GSE12417, and (J) GSE37642 cohort. (K–N) Time-dependent ROC curve analysis of the URGsig based on overall survival in (K) TCGA-LAML, (L) GSE71014, (M) GSE12417, and (N) GSE37642 cohort.

Survival analysis showed that patients in high-risk subgroup had a significantly shorter overall survival compared to those in low-risk subgroup (Fig. 3G). The URGsig displayed robust prognostic performance, with area under the curve (AUC) value of 0.775, 0.804, and 0.828 for 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS prediction, respectively (Fig. 3K). To validate these findings, we assessed the URGsig’s performance in three independent GEO cohorts (GSE71014, GSE12417 and GSE37642), consistently observing strong prognostic predictive ability across all validation sets (Fig. 3H–J, L–N). Furthermore, we compared the performance of URGsig-risk classification with that of ELN-2022 risk stratification system, and found that most of favorable risk and adverse risk patients in ELN system were assigned into low-risk and high-risk subgroups, respectively (Fig. S3).

The relationship of URGsig with clinical characteristics in AML

To investigate the performance of URGsig in different clinical contexts, we conducted stratified analyses in the TCGA-LAML cohort based on various clinicopathological features. The URGsig-risk scores served as a good prognostic risk predictor regardless of age, sex, race, white blood cell count, gene mutation burden, FLT3 status, IDH1/2 status, and NPM1 status (Fig. 4A–D, Fig. S4). Notably, patients in high-risk subgroup had significantly shorter OS in DNMT3A_wt and TP53_wt subgroups (DNMT3A_wt, P < 0.001; TP53_wt, P < 0.001). However, this prognostic stratification was less pronounced in DNMT3A_mut and TP53_mut subgroups (DNMT3A_mut, P = 0.089; TP53_mut, P = 0.157) (Fig. 4B, C).

Stratified survival analysis of URGsig-related subgroups in clinical subtypes. (A–C) Kaplan–Meier survival curve displaying the differences of clinical outcomes between the two URGsig-related molecular subgroups. Samples were stratified by (A) age at diagnosis, (B) DNMT3A status, and (C) TP53 status. (D) Forest plot showing the results of univariate Cox regression that analyze the relationship of URGsig-risk scores with overall survival in different clinical subgroups.

Analysis of biological differences and gene mutation landscapes between URGsig subgroups

To dissect the biological mechanisms underlying prognostic differences between risk subgroups, we performed comprehensive pathway enrichment analyses. The URGsig-related differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were mainly enriched in immune system process, cell adhesion, cell proliferation, cytokine production, leukocyte migration, phagosome, efferocytosis, B cell receptor signaling pathway, and neutrophil extracellular tap formation (Fig. 5A–C). GSEA further revealed significant enrichment of immune-related pathways in low-risk subgroup, particularly in antigen process and presentation, cell killing, phagocytosis, regulation of T cell proliferation (Fig. 5D). Moreover, the high-risk subgroup showed relatively higher mutation frequency of FLT3 (P = 0.007), NPM1(P < 0.001) and DNMT3A (P = 0.007), while exhibiting reduced prevalence of favorable cytogenetic alterations (P = 0.026) (Fig. 5E). Taken together, these results suggest that the URGsig captures distinct immune microenvironment features, with impaired immune surveillance and enhanced immune escape mechanisms potentially contributing to the poor prognosis observed in high-risk subgroup.

Differential analysis of biological and genetic characteristics between low- and high-risk subgroups. (A) Volcano plot showing the differential gene expression profiles between the two subgroups. (B-D) Illustrations of the results of (B) GO, (C) KEGG, and (D) GSEA enrichment analysis. (E) The landscape of gene mutations and cytogenetic alterations in the two subgroups.

The immune landscape heterogeneity between URGsig-based subgroups

Given the established correlation between URG-related molecular subtypes and TME characteristics in AML, we further investigated the immune microenvironment heterogeneity between two risk subgroups in the TCGA-LAML cohort. Significant enrichment in immunosuppressive signature in high-risk subgroup was noted in T cell exhaustion, immune checkpoint blockade resistance, myeloid-derived suppressive cell, and tumor associated macrophage (Fig. 6A). Immune cell infiltration analysis revealed increased presence of monocytes and M2 macrophages in the high-risk subgroup, indicating an immunosuppressive microenvironment conducive to immune evasion (Fig. 6B). Strikingly, we also found significant correlations between URGsig gene expression levels and M2 macrophage infiltrations (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, URGsig-risk scores were significantly associated with the expressions of immune checkpoint genes such as CTLA4, SIRPA, LAG3, and PDCD1 (Fig. 6D). TIDE scores also had a significantly negative correlation with URGsig-risk scores (Fig. 6E). Besides, the higher TME scores, including immune, stromal, and ESTIMATE scores were observed in high-risk subgroups (Fig. 6F–H). These findings collectively suggest that high-risk AML patients subgroup are characterized by a more profoundly immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, potentially contributing to their poorer clinical outcomes.

Differences of TME characteristics between the low- and high-risk subgroup. (A) Heatmap showing the differences of immune-related signature scores between the two subgroups. (B) Comparison of the differences of immune cells infiltrations between the two subgroups. (C) Lollipop plot displaying the correlations between the URGsig-risk scores and M2 macrophage infiltrations. (D) Radar plot displaying the correlations between the expression levels of immune-check-point genes and URGsig-risk scores. (E) Illustration of correlations between TIDE scores and URGsig-risk scores. (F) Illustration of correlations between URGsig-risk scores with immune scores, (G) stromal scores, and (H) ESTIMATE scores. nhigh-risk = 66 and nlow-risk = 66 in TCGA-LAML cohort. *p < 0.05.

The response to chemotherapy and immunotherapy between URGsig-based subgroups

To comprehensively evaluate the therapeutic implications of URGsig, we investigated its association with chemotherapy and immunotherapy response patterns in AML patients. Drug sensitivity analysis revealed significant correlations between URGsig-risk scores and predicted IC50 for 50 therapeutic drugs (Fig. 7A). Specifically, high-risk patients demonstrated reduced sensitivity to several conventional chemotherapeutic agents, including cytarabine and etoposide, as well as targeted therapies such as obatoclax (BCL-2 inhibitor) and lestautinib/midostaurin (tyrosine kinase inhibitors) (Fig. 7B–D). Conversely, high-risk patients showed increased sensitivity to sorafenib (Fig. 7D). Analysis of other targeted therapies revealed that high-risk patients were more responsive to bortezomib (proteasome inhibitor) but less responsive to vorinostat (HDAC inhibitor) compared to low-risk patients (Fig. 7E–F). Additionally, high-risk patients exhibited reduced sensitivity to metformin (Fig. 7G). Moreover, in Beat-AML cohort, we observed that non-responders to standard induction chemotherapy had significantly higher URGsig-risk scores compared to patients having achieved complete remission (Fig. 7H). In GSE66525 cohort, patients at relapse had higher URGsig-risk scores than those at initial diagnosis (Fig. 7I). Furthermore, as Fig. 7J shown, patients in high-risk subgroup were predicted to exhibit higher responsiveness to immunotherapy (Fig. 7J), particularly to anti-CTLA4 treatment (Fig. 7K), potentially attributable to their elevated expression of immune checkpoint molecules. These findings suggest that URGsig may serve as a valuable tool for guiding personalized treatment strategies in AML.

Heterogeneities of drug sensitivity and immunotherapy response in URGsig-based subgroups. (A) Lollipop plot displaying the relationships between the risk scores and drug sensitivity in TCGA-LAML cohort. The color of the lollipop indicates whether the risk scores are related to drug resistance (red) or drug sensitivity (blue). (B–G) Comparisons of predicted IC50 of commonly used drugs between the low-risk (n = 66) and high-risk (n = 66) patients in TCGA-LAML cohort. (H) Comparison of the URGsig-risk scores between complete-remission patients (n = 115) and refractory patients (n = 47) in Beat AML cohort. (I) Comparison of the URGsig-risk scores between newly-diagnosed patients (n = 10) and relapsed patients (n = 10) in GSE66525 cohort. (J) TIDE analysis predicting the difference of response to immunotherapy between the two risk subgroups in TCGA-LAML cohort. (K) Submap analysis predicting the difference of response to anti-PD1 and anti-CTLA4 immunotherapy in the two risk subgroups in TCGA-LAML cohort. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001. nhigh-risk = 66 and nlow-risk = 66 in TCGA-LAML cohort.

Construction of nomogram based on URGsig-risk scores and clinical features

To enhance the practicality of our URGsig model, we developed a comprehensive prognostic nomogram by integrating the URGsig-risk scores with independent clinical prognostic factors identified through multivariate Cox regression analysis, including age, cytogenetic risk grade, FLT3 status, DNMT3A status, and TP53 status (Fig. 8A and Table 1). The nomogram demonstrated strong predictive performance, with higher total points correlating significantly with poorer OS of AML patients (Fig. 8B). Comparative analysis revealed superior discriminative ability of the nomogram over individual predictors, as evidenced by higher AUC values and concordance indices (Fig. 8C–F). The calibration curve visually indicated goodness of fit between the predicted and observed outcomes in nomogram (Fig. 8G). Both DCA and clinical impact curve analysis demonstrated the clinical usefulness and applicability of the nomogram with the best diagnostic value (Fig. 8H-K). The clinical impact curve showed that the nomogram had a good benefit with the wide range and practical ranges of threshold probabilities impacted the patients’ outcomes. When the risk threshold reaches 0.4, the cost benefit ratio reached its peak and the patients obtained best clinical net benefit (Fig. 8K). These analyses collectively establish the nomogram as a valuable tool for risk stratification and treatment planning in AML patients.

Establishment of a novel nomogram incorporating of the URGsig-risk scores. (A) The novel nomogram for each AML patients in TCGA-LAML cohort was constructed based on gene mutation status, cytogenetic risk grade, age, and URGsig-risk scores. *** p < 0.001. (B) Kaplan–Meier curve showing the difference of overall survival between the low- and high-point subgroups. (C–E) Comparisons of time-dependent ROC curve of the nomogram and other risk models. (F) Comparisons of C-index of the nomogram and other risk models. (G) Calibration curve of the nomogram. (H–J) Comparisons of DCA curve between the nomogram and other risk models. (K) Clinical impact curves for the nomogram.

Validation for expression of URGsig-consisting genes in AML clinical samples

To experimentally validate our bioinformatic findings, the expression levels of URGsig core genes (DNAJC10, DNAJB11, ANXA11, MBTPS1, SOD1, and VCP) were examined in bone marrow of AML patients, using immune thrombocytopenia patients as controls (Fig. 9). AML patients showed higher levels of DNAJC10, VCP, ANXA11 than control patients. However, there was no significant differences of the expression of MBTPS1 between AML patients and control patients. Moreover, the mRNA expression of DNAJC10 was higher in relapse patients than initially diagnosed patients, whereas, DNAJB11 showed the opposite expression trend.

Discussion

Current risk assessment strategies for AML patients primarily rely on clinical characteristics, genetic alterations, and minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring3. Treatment of patient with AML is directed by such risk stratification scheme if timely available. Recent advances have highlighted the prognostic significance of molecular markers in understanding tumor progression mechanisms37,38. Among these, URGs have emerged as crucial factors in leukemogenesis and disease progression7. In this study, we have identified distinct URGs-related molecular subtypes and developed a URGsig that effectively predicts clinical outcomes, immunotherapy response, and chemotherapy sensitivity in AML patients.

Our analysis of the TCGA-LAML cohort revealed two distinct molecular clusters based on URGs expression patterns, demonstrating significant survival differences that may be attributed to variations in UPR activation states and immune microenvironment composition. The favorable prognostic significance of UPR activation in AML is well-established, with sustained UPR activation during chemotherapy often leading to AML cell apoptosis12,39. Notably, Cluster A patients exhibited elevated expression of CLAR and improved survival outcomes. CLAR, beyond its role as an endoplasmic chaperon, functions as a nuclear RNA-binding protein that blocks the translation of CEBPA40. CEBPA serve as a crucial factor for survival and differentiation of AML cells15. Conversely, Cluster B patients showed increased expression of DNAJC10, which prevents the PERK-EIF2α-ATF4 branch of UPR and confers resistance to daunorubicin and cytarabine16. The immunosuppressive role of UPR activation is particularly intriguing, with XBP1 upregulation associated with reduced infiltration of T cell infiltration, impaired MHC-I expression, and MDSCs activation19,41,42. However, XBP1 deficiency in T cells enhances anti-tumor immunity, delays tumor progression, and prolongs survival in mouse models43. In our findings, Cluster B demonstrated higher immune checkpoints gene expression (PDCD1, CTLA4 and LAG3) and increased T cell infiltration, the overall immune microenvironment remained suppressive, suggesting potential benefit from immune checkpoint inhibition therapy.

Our URGsig, derived from statistically significant prognostic URGs, demonstrated robust predictive accuracy for AML patient outcomes, with AUC values exceeding 0.7 for prediction of 1, 3, and 5-year OS. The patients in the high URGsig-score subgroup exhibited worse clinical outcomes, consistent with findings from previous studies in solid tumors20,21,22. The prognostic value of URGsig was also validated in multiple independent AML cohorts. Moreover, the performance of our URGsig was comparable to that of the ELN risk-stratification scheme in prognostic prediction3, underscoring its robustness and reproducibility. Furthermore, the development of a comprehensive prognostic nomogram incorporating URGsig and clinical features provides a practical tool for prognosis prediction. Genetic analysis revealed distinct molecular profiles between risk subgroups, with the high-risk subgroup showing increased FLT3 mutations and reduced favorable cytogenetic alterations. Of note, DNMT3A and TP53 mutations significantly impacted outcomes in low-risk patients. DNMT3A and TP53 mutations lead to genome instability and increase the clone heterogeneity of AML cell, which are associated with relapse and poor prognosis44,45,46. These results suggest that it is not sufficient to predict prognosis solely based on single signatures due to the complexity of AML. However, targeted therapies against these specific mutations still have potential to provide some benefits to AML patients regardless of their risk subgroups.

Therapeutic response analysis revealed differential drug sensitivity patterns between risk subgroups. Low-risk patients demonstrated greater sensitivity to conventional chemotherapies, consistent with their heightened UPR activation state12,16. High-risk patients, while generally less responsive to standard therapies, showed particular sensitivity to sorafenib, potentially related to DNAJC10 overexpression16. Similarly, we found the elevated expression of DNAJC10 in high-risk subgroup, highlighting its crucial role in targeted therapy. Additionally, the AML patients in high-risk subgroup were predicted to respond to anti-PD1 and anti-CTLA4 treatment, which may be attributed to higher expression of inhibitory immune check point genes. The predicted responsiveness of high-risk patients to immune checkpoint inhibitors (anti-PD1 and anti-CTLA4) offers promising therapeutic avenues for this challenging subgroup.

Taking together, while our study establishes URGsig as a valuable independent prognostic factor and treatment guidance tool, several limitations warrant consideration. Only through bioinformatics analyses of public data revealed the expression characteristics and prognostic value of URGsig. Additionally, the heterogeneity of clinical and gene expression data obtained from different source may have affected the accuracy of results. Most importantly, the prognostic value of URGsig requires validation through multicenter, large-scale real word cohort studies. Future researches should focus on functional validation of these findings and elucidation of the mechanistic roles of URGsig in AML pathogenesis to fully realize their clinical potential.

Data availability

All data are available from the Genomic Data Commons (GDC) (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) and GEO (https://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) database within the article.

References

Pollyea, D. A. et al. Acute myeloid leukemia, version 3.2023, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. Natl. Comprehensive Cancer Netw. JNCCN 21, 503–513. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2023.0025 (2023).

Röllig, C. et al. Long-term prognosis of acute myeloid leukemia according to the new genetic risk classification of the European LeukemiaNet recommendations: evaluation of the proposed reporting system. J. Clin. Oncol. Offic. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 29, 2758–2765. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2010.32.8500 (2011).

Döhner, H. et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2022 recommendations from an international expert panel on behalf of the ELN. Blood 140, 1345–1377. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2022016867 (2022).

Chen, Z. et al. A novel 4-mRNA signature predicts the overall survival in acute myeloid leukemia. Am. J. Hematol. 96, 1385–1395. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.26309 (2021).

Kong, W. et al. An immunity and pyroptosis gene-pair signature predicts overall survival in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 36, 2384–2395. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-022-01662-6 (2022).

Ragaini, S. et al. An IDO1-related immune gene signature predicts overall survival in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv. 6, 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2021004878 (2022).

Khateb, A. & Ronai, Z. A. Unfolded protein response in leukemia: from basic understanding to therapeutic opportunities. Trends Cancer 6, 960–973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trecan.2020.05.012 (2020).

Barton, B. M. et al. IRE1α-XBP1 safeguards hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells by restricting pro-leukemogenic gene programs. Nat. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-024-02063-w (2025).

Vetrie, D., Helgason, G. V. & Copland, M. The leukaemia stem cell: similarities, differences and clinical prospects in CML and AML. Nat. Rev. Cancer 20, 158–173. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-019-0230-9 (2020).

Sun, H. et al. Inhibition of IRE1α-driven pro-survival pathways is a promising therapeutic application in acute myeloid leukemia. Oncotarget 7, 18736–18749. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.7702 (2016).

Zhou, C. et al. JUN is a key transcriptional regulator of the unfolded protein response in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 31, 1196–1205. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2016.329 (2017).

Schardt, J. A., Weber, D., Eyholzer, M., Mueller, B. U. & Pabst, T. Activation of the unfolded protein response is associated with favorable prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res.: An office. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 15, 3834–3841. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-08-2870 (2009).

Haefliger, S. et al. Protein disulfide isomerase blocks CEBPA translation and is up-regulated during the unfolded protein response in AML. Blood 117, 5931–5940. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2010-08-304485 (2011).

Hoff, F. W. et al. Valosin-containing protein (VCP/p97) is prognostically unfavorable in pediatric AML, and negatively correlates with unfolded protein response proteins IRE1 and GRP78: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Proteomics. Clin. Appl. 17, e2200109. https://doi.org/10.1002/prca.202200109 (2023).

Du, M. et al. C/EBPα-p30 confers AML cell susceptibility to the terminal unfolded protein response and resistance to Venetoclax by activating DDIT3 transcription. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res.: CR 43, 79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-024-02975-3 (2024).

Li, M. et al. DNAJC10 maintains survival and self-renewal of leukemia stem cells through PERK branch of the unfolded protein response. Haematologica 109, 751–764. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2023.282691 (2024).

Zhou, C. et al. HMGCS1 drives drug-resistance in acute myeloid leukemia through endoplasmic reticulum-UPR-mitochondria axis. Biomed. Pharmacother. Biomed. Pharmacotherapie 137, 111378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111378 (2021).

Cubillos-Ruiz, J. R., Bettigole, S. E. & Glimcher, L. H. Tumorigenic and immunosuppressive effects of endoplasmic reticulum stress in cancer. Cell 168, 692–706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.004 (2017).

Yang, Z. et al. Cancer cell-intrinsic XBP1 drives immunosuppressive reprogramming of intratumoral myeloid cells by promoting cholesterol production. Cell Metabolism 34, 2018-2035.e2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2022.10.010 (2022).

Fang, L. et al. Identification of an unfolded protein response-related signature for predicting the prognosis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Front. Oncol. 12, 1060508. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.1060508 (2022).

Zhang, S. et al. A novel mitochondrial unfolded protein response-related risk signature to predict prognosis, immunotherapy and sorafenib sensitivity in hepatocellular carcinoma. Apoptosis : Int J. Program. Cell Death 29, 768–784. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10495-024-01945-6 (2024).

Shi, C. et al. A novel prognostic signature in osteosarcoma characterised from the perspective of unfolded protein response. Clin. Transl. Med. 12, e750. https://doi.org/10.1002/ctm2.750 (2022).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 (2014).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucl. Acids Res. 28, 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci.: Publ. Protein Soc. 28, 1947–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3715 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucl. Acids Res. 53, D672-d677. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2025).

Yu, G., Wang, L. G., Han, Y. & He, Q. Y. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omics: J. Integrative Biol. 16, 284–287. https://doi.org/10.1089/omi.2011.0118 (2012).

Mayakonda, A., Lin, D. C., Assenov, Y., Plass, C. & Koeffler, H. P. Maftools: efficient and comprehensive analysis of somatic variants in cancer. Genome Res. 28, 1747–1756. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.239244.118 (2018).

Mermel, C. H. et al. GISTIC2.0 facilitates sensitive and confident localization of the targets of focal somatic copy-number alteration in human cancers. Genome Biol. 12, R41. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2011-12-4-r41 (2011).

von Mering, C. et al. STRING: known and predicted protein-protein associations, integrated and transferred across organisms. Nucl. Acids Res. 33, D433-437. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gki005 (2005).

Newman, A. M. et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat. Methods 12, 453–457. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3337 (2015).

Yoshihara, K. et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat. Commun. 4, 2612. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3612 (2013).

Zeng, D. et al. IOBR: multi-omics immuno-oncology biological research to decode tumor microenvironment and signatures. Front. Immunol. 12, 687975. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.687975 (2021).

Geeleher, P., Cox, N. & Huang, R. S. pRRophetic: an R package for prediction of clinical chemotherapeutic response from tumor gene expression levels. PloS ONE 9, e107468. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0107468 (2014).

Jiang, P. et al. Signatures of T cell dysfunction and exclusion predict cancer immunotherapy response. Nat. Med. 24, 1550–1558. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0136-1 (2018).

Hoshida, Y., Brunet, J.-P., Tamayo, P., Golub, T. R. & Mesirov, J. P. Subclass mapping: identifying common subtypes in independent disease data sets. PLOS ONE 2, e1195. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0001195 (2007).

Mathioudaki, A. et al. The remission status of AML patients after allo-HCT is associated with a distinct single-cell bone marrow T-cell signature. Blood 143, 1269–1281. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2023021815 (2024).

Huang, B. J. et al. Integrated stem cell signature and cytomolecular risk determination in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Nat. Commun. 13, 5487. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-33244-6 (2022).

Philippe, C. et al. Pivotal role of the endoplasmic reticulum stress-related XBP1s/miR-22/SIRT1 axis in acute myeloid leukemia apoptosis and response to chemotherapy. Leukemia https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-024-02321-8 (2024).

Timchenko, L. T., Iakova, P., Welm, A. L., Cai, Z. J. & Timchenko, N. A. Calreticulin interacts with C/EBPalpha and C/EBPbeta mRNAs and represses translation of C/EBP proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 7242–7257. https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.22.20.7242-7257.2002 (2002).

Song, M. et al. IRE1α-XBP1 controls T cell function in ovarian cancer by regulating mitochondrial activity. Nature 562, 423–428. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0597-x (2018).

de Almeida, S. F., Fleming, J. V., Azevedo, J. E., Carmo-Fonseca, M. & de Sousa, M. Stimulation of an unfolded protein response impairs MHC class I expression. J. Immunol. 178, 3612–3619. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3612 (2007).

Cubillos-Ruiz, J. R., Bettigole, S. E. & Glimcher, L. H. Molecular pathways: immunosuppressive roles of IRE1α-XBP1 signaling in dendritic cells of the tumor microenvironment. Clin. Cancer Res. Offic. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 22, 2121–2126. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-15-1570 (2016).

Huang, Y. H. et al. Systematic profiling of DNMT3A variants reveals protein instability mediated by the DCAF8 E3 ubiquitin ligase adaptor. Cancer Discov. 12, 220–235. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-21-0560 (2022).

Ley, T. J. et al. DNMT3A mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl. J. Med. 363, 2424–2433. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1005143 (2010).

Fleming, S., Tsai, X. C., Morris, R., Hou, H. A. & Wei, A. H. TP53 status and impact on AML prognosis within the ELN 2022 risk classification. Blood 142, 2029–2033. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2023020855 (2023).

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.F. and L.W.: writing-original draft preparation, manuscript, investigation, analysis, and figure preparation. C.Y. and X.H.: conceptualization, methodology and supervision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fei, L., Wenjie, L., Yanan, C. et al. Identification of a novel unfolded protein response related signature for predicting the prognosis of acute myeloid leukemia. Sci Rep 15, 6705 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91524-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91524-9