Abstract

The safe and efficient operation of smart Intelligent vehicles relies heavily on accurate trajectory prediction techniques. Existing methods improve prediction accuracy by introducing scene context information, but lack the causal perspective to explain why scene context improves prediction performance. In addition, current multimodal trajectory prediction methods are mostly target-driven and implicitly fused, relying too much on the density of candidate targets, as well as ignoring the road rule constraints, which leads to a lack of anthropomorphic properties in the model’s prediction results. To this end, this paper proposes a novel multimodal trajectory prediction model, CCTP-Net, which introduces causal interventions in the encoding phase to balance the influence of spatio-temporal features of the learned scene context on the trajectory. A node refinement strategy based on the cognitive properties of human drivers is designed between the feature aggregator and the decoder by selectively traversing the lane graph in order to identify key road node features. The extracted important nodes are finally used for multimodal trajectory decoding after counterfactual reasoning. CCTP-Net experiments on the publicly available dataset nuScenes show that the model has significant advantages in multimodal trajectory prediction in complex scenarios, verifying its effectiveness and reliability. This study provides new theoretical perspectives and technical paths for trajectory prediction of intelligent connected vehicles, which is expected to promote the further development of related technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Trajectory prediction is a critical research topic in the field of Intelligent Connected Vehicles (ICVs), aiming to predict the future motion trajectories by leveraging comprehensive kinematic features of vehicles and beyond-line-of-sight surrounding environment information collected from ICV sensors and roadside infrastructure1. In complex scenarios, accurate and reliable vehicle trajectory prediction is fundamental to enabling key ICV functions such as safety warnings and driver assistance systems.

Current trajectory prediction techniques heavily rely on deep learning, as it can consider various physical factors, interactions between nearby agents, and incorporate scene context to adapt to complex traffic scenarios. High-Definition (HD) maps, for instance, provide rich scene context information. Methods such as VectorNet2 and LaneGNC3 integrate multiple input sources, including trajectory position, vehicle yaw angle, speed, and acceleration, while embedding road structures into fusion networks for enhanced prediction accuracy. Several subsequent studies4,5 have further demonstrated the effectiveness of incorporating scene context.

Although these methods improve short-term prediction performance, they fail to provide a deep understanding of the causal relationships between trajectories, scene context, and hidden features. They do not explain, from a causal perspective, why fusing trajectory information with scene context leads to improved prediction performance. The use of multi-source input features can result in confusion paths when different features propagate through the network, causing the model to incorrectly learn strong, unstable correlations between trajectories and hidden features tied to specific historical data. These learned correlations may no longer hold when the scene context changes. Consequently, the generalization ability and interpretability of current trajectory prediction models on out-of-distribution data need further improvement.

Multimodal prediction presents another challenge in trajectory forecasting. Numerous studies have proposed outputting multiple possible future trajectories for the target vehicle to capture the inherent multimodality of future motion. To ensure that the multimodal trajectories conform to scene constraints, method6 explored a goal-driven strategy to improve trajectory predictions covering all potential future behaviors of the vehicle. This strategy uses a set of dense candidate goals to represent the feasible destinations of the vehicle. However, these methods typically tend to predict the most frequently observed patterns in the training data, failing to make human-like driving decisions as human drivers would. While this strategy reduces trajectory uncertainty during model optimization, its performance is highly dependent on the density of the candidate goals and lacks the ability to generate human-like multimodal predictions. These approaches miss the opportunity to apply insights from cognitive science to produce human-inspired predictions. How to prioritize important candidate targets, similar to human drivers, while reducing the number of candidates and improving prediction accuracy, is a pressing issue that needs to be addressed.

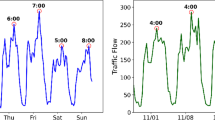

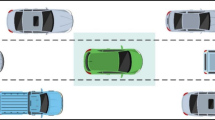

To cope with the above challenges, the CCTP-Net model is proposed in this paper. Firstly, we constructed the trajectory prediction causal model from the causality perspective, as shown in Fig. 1a. \({C}_{t}\) denotes the current road scene information, Temporal denotes the temporal features of the trajectory sequence, Spatial denotes its spatial dimension features, and Spatio-temporal causal features are the hidden features after fusion. In the original model, \({C}_{t}\) and the trajectory are treated as independent; however, they are inherently causally related. This causal relationship arises because vehicles demonstrate distinct trajectories depending on the specific scenarios they encounter. For instance, the length of a roundabout or intersection encountered is significantly affected. We use the front-door path \(Tra{j}_{t}\to \left(S,T\right)\to {F}_{t}\) to eliminate the spurious correlation between \(Tra{j}_{t}\) and \({F}_{t}\) in the back-door path \(Tra{j}_{t}\leftarrow {C}_{t}\to {F}_{t}\), so that the model learns the real causal relationship, which makes the model learn the true causal effect. The use of counterfactual reasoning on Hiden Features prior to decoding allows the model to consider trajectories that could occur in different contexts. We introduce the road scene context information \({C}_{f}\), at future moments, into the hidden features to obtain new spatio-temporal causal features adapted to future scenarios, thus enhancing the model’s understanding of multiple possibilities and uncertainties. Moreover, existing research7,8 has demonstrated that in highly dynamic driving environments, the processing capacity of the human brain is limited, allowing drivers to effectively process information from only a few surrounding vehicles. The driver’s visual area dynamically adjusts with speed: at higher speeds, the visual area narrows to focus attention, and expands at lower speeds to gain broader peripheral awareness, a driving cognitive property illustrated in Fig. 1b. This cognitive property provides important inspiration for trajectory prediction. Therefore, to address the drawbacks of poor anthropomorphism and dense candidate targets in goal-driven multimodal trajectory-based approaches, we incorporate the insights derived from this dynamic driving cognition mechanism into a node refinement strategy for better anthropomorphic multimodal trajectory prediction. The CCTP-Net proposed in this paper is evaluated on a large-scale real-world benchmark, nuScenes9, and extensive ablation experiments are also conducted to validate the validity and reliability of the model. The experiments show that the method based on causal reasoning and driving cognitive properties exhibits excellent accuracy and stability. In summary, the main contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

1.

For vector-based prediction models that fail to explain why incorporating scene context information significantly improves prediction performance, this study establishes a comprehensive causal structure for trajectory prediction from the perspective of causal relationships. By leveraging causal intervention within the causal reasoning framework, it eliminates implicit confounding bias. Furthermore, counterfactual reasoning is employed to account for changes in future scenarios, enabling the model to fairly learn the spatiotemporal features within the scene context. This approach allows the model to automatically uncover stable relationships in the observed data while avoiding spurious correlations influenced solely by individual trajectories.

-

2.

To address the uncertainty in complex scenarios and the multimodality of trajectories, CCTP-Net designs a comprehensive node refinement strategy during the information fusion and decoding prediction stages to integrate effective scene context information. This strategy is based on the strong topological constraints of lane graphs and utilizes the cognitive characteristics of human drivers to guide vehicle movement within the lane graph. Without requiring dense candidate targets, the strategy adaptively adjusts future trajectories, further assisting the model in predicting human-like multimodal trajectories.

-

3.

CCTP-Net is validated on the public nuScenes dataset, and experimental results show that for predicting five trajectories, minADE and MR improved by 2.4% and 3.8%, respectively, compared to the best baseline model, while minFDE improved by 4.3%. Additionally, the visualization results demonstrate stronger robustness and interpretability.

Trajectory prediction related work

Scene representation

In existing trajectory prediction research, Wang et al.10 and Liao et al.11 have utilized map-free trajectory prediction methods that model only the historical observation trajectories of vehicles. While these models feature simple and lightweight architectures, they are clearly constrained in scenarios with straightforward geometric structures, such as highways, where traffic participants exhibit high homogeneity. In complex urban traffic environments, these methods struggle to perform effectively.

Grid-based techniques use bird’s-eye view (BEV) images to map continuous spatial information into discrete pixel grids, covering both static and dynamic entities’ historical data, as well as semantic map details. For instance, CoverNet12 and Context-Aware Timewise13 utilize rasterized scenes as input, extracting map elements such as lane boundaries, crosswalks, and traffic lights from high-definition maps. These elements are rendered into bird’s-eye view images using different colors or masks to allow convolutional neural networks to capture the scene context. However, the rasterization process inevitably leads to the loss of geometric and temporal details.

High-definition (HD) maps serve as a critical component within the autonomous driving technology stack, especially in L3 and above intelligent connected vehicles (ICVs). These pre-collected, highly precise maps are foundational to autonomous driving, providing centimeter-level geometric and semantic information on road boundaries, lane dividers, lane centerlines, crosswalks, traffic signs, and road markings14. In particular, the emergence of online vectorised high-precision map construction work15,16 can make up for the shortcomings of single-vehicle intelligence in perception, data, and computation, which can effectively make up for the lack of vehicle-side sensors and model training, and reduce the rigidity of the demand for high computing power at the vehicle side. They are proven to be an indispensable part of enhancing self-driving car situational awareness and navigation judgement in downstream prediction tasks. In particular, graph-based methods represented by VectorNet2 and LaneGCN3, which have the advantage of explicitly modelling scene entities and their interactions in the driving scenario, significantly improve the performance of trajectory prediction. Transformer and attention mechanisms can also be used for trajectory prediction tasks17,18,19. These approaches integrate the scene context and inter-vehicle interactions to improve the performance of trajectory prediction by using Transformer to model the interactions of agents in vectorised HD maps. Therefore, in this paper, we adopt the same lane diagram modeling method as VectorNet in the dataset preprocessing stage. Meanwhile, for the implicit interactions with heterogeneous traffic participants, we also adopt an approach based on the attention mechanism to capture them.

Causal inference

Causal reasoning is an important area of research in a variety of fields such as statistics, medicine, biology, computer science and economics20. Recently, researchers have started to use causality to study areas related to autonomous driving. Li et al.21 used causality to study the factors involved in decision making for an end-to-end model of autonomous driving. In line with this we found that even models based on composite networks such as Transformer can only represent that there is a direct correlation between the context of the traffic scene and the trajectory data. However, the real world is driven by causality rather than simple correlation, and correlation is not the same as causation. To the best of our knowledge, few researchers have studied trajectory prediction from a causal perspective. Huang et al.22 implemented counterfactual reasoning operations by introducing masks to process the input data and control the probability values of randomly losing nodes or agents during model training to obtain interpretability of behavioural prediction models. This masking approach can only intervene in the data at specific moments and is not based on explicit causal graphs or causal modelling. The results of such inferences may be limited to the correlation level and fail to reveal deeper causal relationships. In the latest research on causal models for trajectory prediction, Liu et al.23 proposed a causal model based on spatio-temporal structure, and they constructed a causal graph on an implicit fusion-based method to analyze the causal relationship between trajectories in the current scene, but the implicit fusion method does not specifically reflect the guiding role of scene information on trajectory prediction, so the extracted spatio-temporal features are semantically deficient. For this reason, this paper constructs a perfect causal structure graph on the graph structure-based trajectory prediction paradigm, and studies the causal relationship between scene context and trajectory data with the help of causal inference methods, so as to better reveal the significance of scene context on trajectory prediction.

Multimodal prediction

Predicting multimodal trajectories is more conducive to coping with uncertain behaviours and scenario constraints of intelligences than single trajectories. To increase modal diversity, Gu et al.24 divided the prediction goal into two phases: goal prediction and motion completion. They first randomly sampled several goal regions from the map and then completed the trajectory prediction conditional on each goal region. Similarly, the goal-driven methods GOHOME25, THOMAS26 relied on predictive heat maps and sampled a large number of target points to achieve goal prediction before generating a complete trajectory. Although the intended relevance of the target points is high, such models still do not take into account the strong constraints imposed by the road structure on the movement, and also generate redundant computations due to the large number of unselected target points. Deo et al.27 exploited the road structure by traversing the full set of destination nodes through a graph to learn a probability distribution for sampling. Varadarajan et al.28 used a set of fixed anchor points corresponding to the pattern of the trajectory distribution to regress the predicted multimodal trajectories. Zhong et al.29 proposed a method that treated the set of historical trajectories at the current location of the intelligent as a priori information to narrow the search space of potential future trajectories. Lu et al.30 used Conditional Variational Autoencoder (CVAE) to resolve trajectory uncertainty by capturing the distribution of endpoints conditional on the invariance principle of the cross-domain invariant features. Hu et al.31 with the work26 divided the vehicle trajectories into transverse and longitudinal routes and also utilized Conditional Variational Autoencoder (CVAE) to capture the trajectory uncertainty. In this paper, it is also argued that this lateral and longitudinal decoupling method can effectively resolve the trajectory uncertainty and thus predict multimodal trajectories.

Scene understanding and decision-making are key breakthroughs in enhancing the trajectory prediction capabilities of autonomous vehicles. We advocate incorporating human driving cognition into the prediction process to improve the model’s capability and interpretability. Liao et al.32 proposed BAT, a model that integrates insights and findings from traffic psychology, human behavior, and decision-making while accounting for uncertainty and variability in predictions. Additionally, Liao et al.7 introduced a teacher-student knowledge distillation framework inspired by human cognitive processes to achieve trajectory prediction. However, such methods have only been validated on datasets like NGSIM and HighD, which have lower information dimensions and cannot fully reflect the complexity of real-world road scenarios, thereby limiting their ability to model complex traffic environments.

In contrast, the core insight of our study is to incorporate the cognitive mechanism of human drivers’ range of vision changing with vehicle speed during driving into a graph-based prediction paradigm. In this mechanism, the driver’s field of view varies adaptively with vehicle speed, which in turn determines the attention paid to the target node. We filter out irrelevant target nodes based on strong lane constraints, thus avoiding the need for full graph traversal and minimizing the interference of unarticulated features in edge regions. By introducing this cognitive mechanism, our model is able to mimic the human reasoning process to a certain extent, which makes the prediction results more anthropomorphic and improves the predictive ability of the model.

Methods

Architecture of CCTP-Net

Figure 2 illustrates the overall architecture of CCTP-Net, the multimodal trajectory prediction model proposed in this paper. First, we introduce a multi-scale encoder to separately extract trajectory features (“Architecture of CCTP-Net” section). Subsequently, causal intervention is applied to enable the model to fairly learn the representation of trajectories in the spatiotemporal feature dimensions. We then use masked attention and Graph Attention Networks (GAT)33 to fuse the encoded features of surrounding traffic participants with vectorized lane encodings (“Scene encoding” section). Next, through our designed node refinement module based on human driver cognitive mechanisms, we adaptively select fine-grained nodes. These nodes undergo counterfactual reasoning, and features are aggregated along the candidate nodes to generate the multimodal decoding global context vector required by the decoder (“Feature aggregation” section).

Scene encoding

Given that the input trajectory in is a complex time series, and similarly the lane graph is an input source with a sequence structure, we design a multi-scale encoder to encode the trajectory data, and also encode the lane graph using a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) to get their feature representations in the time dimension.

Multi-scale trajectory coding

The encoder first processes the raw input features. In order to fully describe the dynamic behaviour of the vehicle, we first perform fusion at the feature level to obtain the input sequence Traj serves as the history trajectory for the model encoder input. The input sequence features include aerial view coordinates, velocity, acceleration, yaw angle, and category at moment t. Feature-level fusion reduces the dependence on a single feature. Thus, the input features are represented as \(\left[{x}_{t}^{i},{y}_{t}^{i},{v}_{t}^{i},{a}_{t}^{i},{\varphi }_{t}^{i}\right]\). The input dimensions of target vehicles and neighbouring participants are \({f}_{t\mathit{arg}et}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{B\times T\times F}\), \({f}_{sur}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{N\times T\times F}\), and T is the history time step. In order to consider the impact of the interaction importance of different types of traffic participants on the task, the dynamic targets in the scene are divided into the target vehicle, the surrounding traffic participants (people, cars, and bicycles), and these heterogeneous agents are coded independently.

In the trajectory prediction task, efficient encoding and prediction are crucial without compromising performance. We select the GRU as the encoder’s key component due to its ability to capture temporal dependencies while ensuring computational efficiency, making it ideal for resource-constrained scenarios. To address irregularities and noise in historical trajectory data, we first apply Gaussian smoothing to the trajectory points. Subsequently, a pooling operation is employed to further smooth the data and reduce noise across both time and feature dimensions, which is then remapped to the original dimensions. Average pooling of historical trajectories is conducted using small time windows to capture short-term dependencies, leading to a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics within the trajectory sequence. While Gaussian smoothing and average pooling reduce noise, they also result in some loss of detailed information. To address this, we remap the original inputs with linear variations, concatenate them, and then adjust the dimensions to meet the requirements of the GRU, creating a new feature representation. Finally, the GRU encodes this new feature sequence to capture temporal dependencies throughout the entire sequence, facilitating multi-scale and sequential feature extraction. The detailed internal structure of this encoder is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Taking the target vehicle history trajectory encoding \({\varepsilon }_{\text{sur}}\) as an example, its formula is expressed as follows. Where the bluepink trapezoid represents the LeakRelu activation function and the linear layer. The Gaussian represents the Gaussian smoothing of only the trajectory points in the input features, which maintains more details of the trajectory by a small smoothing operation and removes a part of the noise at the same time, and the smoothing process is expressed as :

\(AP\) denotes two different average pooling operations for the feature dimension and the time dimension, formulated as:

The symbol [ ] is the Concat function, and the final spliced vector is fed into the GRU to obtain the final target vehicle trajectory encoding \({\varepsilon }_{\text{sur}}\) , which is internally computationally represented as:

Lane graph representation

Roads as one of the three elements of traffic, are indispensable for modelling traffic scenarios. The centerline of each lane provides the direction of traffic flow as well as spatial information. Graph-based modelling approaches have proven effective27. A vector sequence of road centre lines in a high precision map is constructed as a directed lane graph \(\mathcal{G}=\left(\mathcal{V},E\right)\). The node \(\mathcal{V}\) represents the centreline of the lanes in a certain area around the target vehicle, and the longer lane centrelines are divided into multiple lines equal in length, each of which is considered as a node. To refine the features of the nodes, each lane centreline is further divided into N segments, and the feature vector of each segment is specifically denoted as \({N}_{n}^{v}=\left[{x}_{n}^{v},{y}_{n}^{v},{\varphi }_{n}^{v},{\zeta }_{n}^{v}\right]\). \({x}_{n}^{v},{y}_{n}^{v},{\varphi }_{n}^{v}\) denote the position and yaw angle of the nth lane segment in a given node, respectively, and \({\zeta }_{n}^{v}\) serves as a flag bit to mark whether it is on the stop line and the pedestrian crossings. \(E\) is the edge between nodes, including both successor and neighbour. Successor edges point to one or more successor nodes, or multiple nodes with the same successor node. Neighbourhood indicates that adjacent lane nodes are reachable from each other. This captures both the geometric features of the lane centreline and scene information such as traffic flow direction. As lane segments also have a sequential structure, the initial lane nodes are obtained from the input, and a series of nodes represent the lane centreline which is also a sequence of features with a well-defined order, here only the node features are encoded using a GRU, with a hidden unit of 32, and the output node features are encoded as \({\varepsilon }_{node}\), formulated as:

Vehicle behaviors in each predicted scenario (e.g., lane keeping, lane changing, turning.) can be implicitly mapped to this graph. Meanwhile, the relationship of edges plays an important role in enhancing the motion constraints to ensure the consistency and physical accessibility of the model to the real scenario. By using the above approach, this lane graph representation is rich in road semantic information such as lane topology, intersections and traffic flow directions, providing an ideal source of structured information. The method offers guidance for the subsequent exploration of reachable nodes of target vehicles in the graph.

Feature aggregation

Trajectory causal intervention

Before feature aggregation, we want to eliminate pseudo-correlation in the model. As shown in Fig. 1, the input trajectory \(Traj\) and the hidden feature HiddenFeature are pseudo-correlated due to the presence of the scene context \({C}_{t}\), because the scene context \({C}_{t}\) affects both Traj and HiddenFeature, which may result in the HiddenFeature learning the more general features induced by Traj and ignoring the \({C}_{t}\) for trajectories, and thus the model fails to learn the true effect effect: \(Traj\to (Temporal,Spatial)\to HiddenFeature\).This pseudo-correlation is reflected in the transfer of information in the non-causal direction, which is also known as the backdoor path, and is specifically represented as \(Traj\leftarrow {C}_{t}\to Hiden Feature\). In order to adjust the pseudo-correlation interference brought by the backdoor path, it is necessary to use the causal path as the backdoor path, which is the most important factor in the trajectory of the HiddenFeature pseudo-correlation interference, the front-door criterion in the causal inference paradigm needs to be used. The existence of the path due to \({C}_{t}\to Traj\to (Temporal,Spatial)\to HiddenFeature\leftarrow {C}_{t}\) in the figure precisely cuts off the above backdoor path. Similar to previous work3, the spatiotemporal features of the trajectory are decoupled and then represented as comprehensive spatiotemporal features of the trajectory. Temporal and Spatial are used as mediator variables to denote the temporal and spatial features, respectively, that are extracted through a specific network. Through the mediator variables, the model is able to learn the relationship between the input data and the potential state more fairly and robustly.

The feature aggregation method is based on a constructed lane graph. Therefore, dynamic spatio-temporal features need to be embedded into the nodes of the lane graph. In “Scene encoding” section, we obtained the temporal features of the trajectory. To learn the impact of the scene context on the spatial features of the trajectory, it is necessary to use causal intervention to obtain a comprehensive representation of the trajectory features. The causal intervention on the input historical trajectories is denoted as \(do\left(Traj\right)\) following the paradigm of causal inference. The specific \(do\left(Traj\right)\) operation is to use the multiscale encoder to obtain the temporal feature \({\varepsilon }_{agent}\) of Traj and the scene feature \({\varepsilon }_{node}\) of the map encoder, and then cross-source fusion of \({\varepsilon }_{agent}\) and \({\varepsilon }_{node}\) to obtain the new representation \({\varepsilon }_{ST}\) of Traj on the road scene context, as shown in Fig. 4. In this way, the effect of \({C}_{t}\) on HiddenFeature is indirectly reflected through the representation \({\varepsilon }_{ST}\) of \({\varepsilon }_{agent}\) and \({\varepsilon }_{node}\), rather than directly affecting HiddenFeature. This ensures that the feature information is delivered on the correct causal path. With the causal intervention and the front door criterion, the model filters out the pseudo-correlated interference caused by \({C}_{t}\) while retaining the useful scene information, thus ensuring the accuracy of causal inference while extracting useful contextual information from the complex spatio-temporal environment. Through causal intervention, the model learns a more realistic causal relationship: \(Traj\to (Temporal,Spatial)\to HF\).

The causal intervention process of the trajectory is shown in Fig. 4. The deformable cross-attention mechanism34 is able to combine vehicle trajectory information with spatial features of road nodes (e.g., road structure, node locations, stop lines, etc.) to generate a more spatially adaptive representation of trajectory features. We take the feature dimensions after the two cross-attention Concat, map them to the dimensions of the original \({\varepsilon }_{agent}\) and activate them nonlinearly, σ denotes the LeakyRelu nonlinear activation function, which can be expressed as:

Lane graph node feature aggregation

In the encoding phase, trajectory encoding and lane node encoding are processed independently, and the interactions between traffic participants and between traffic participants and roads are not considered for the time being. To enable indirect access to historical kinematic features for lane node traversal in the subsequent strategy section. We used masked attention to incrementally fuse two feature sources from road nodes and historical trajectories respectively. Masked multi-attention still acts as cross-attention, which can focus on agent trajectories associated with road nodes and weight the trajectories according to the attentional weights to update the lane node feature encoding. This process captures the interaction between neighboring agents and the road environment at both dynamic and static levels. To filter irrelevant information, we use mask information to focus only on traffic participants within a distance threshold near the lane node. The meaning of the mask is that each lane node, has a vector to determine which neighbors should be considered. The linear projection node encoding \({\varepsilon }_{node}\) is used as the query Q. Notably, the trajectory feature \({\varepsilon }_{ST}\) after \(do\left(Traj\right)\) is needed here, and the linear projection \({\varepsilon }_{ST}\) obtains the key K and the value V, which is spliced by the output original encoding \({\varepsilon }_{node}\) after the masking attention, and is mapped back to the original dimension through the linear layer.

These steps address the lack of long-range dependencies between neighboring agent trajectories and road node sequences in the encoder, further enhancing the feature representation of lane nodes. By embedding the temporal features and spatial locations of neighboring agents into the lane nodes through masked multi-head attention, the method effectively aggregates both dynamic and static features. This approach mitigates the bias caused by relying solely on either dynamic trajectory features or static road features, ultimately enabling lane nodes to achieve a more refined and detailed representation.

After the lane node feature encoding is enhanced by the above fusion network, GAT is used in order to enable effective message passing between nodes and their neighbours in the lane graph. Features are aggregated from their neighbour nodes to the target node based on their importance. Each layer of GAT utilizes a multi-head attention mechanism, but to maintain consistent input and output dimensions, a single-head implementation is used. The second GAT layer extracts deeper local node features, incorporating residual connections between layers to facilitate aggregation of scene context along all reachable edge directions. This process embeds spatio-temporal features within the lane graph, helping the model capture causal relationships. By interacting with spatio-temporal features across nodes, the model better understands vehicle movement patterns in the road environment, which aids in handling complex causal pathways during trajectory prediction. The output of this process serves as the final lane graph node features.

Driving cognition based node refinement strategy

The traditional approach sends the features after feature aggregation directly to the decoder for decoding to obtain future trajectories. However, we argue that all features after implicit fusion are not required by the decoder. Our approach introduces a strategy block between the feature aggregation phase and the decoder, aiming to identify key contextual elements and aggregate additional information from these critical inputs to further refine the predictions.

Lane graph traversal

The key to designing the strategy is to attempt to filter the most relevant target nodes in order to exclude non-junction point features. This differs from the target point-based driver that directly provides a large number of target points. The core of our designed strategy is to traverse through the lane graph with the purpose of filtering lane nodes. However, there are three problems in traversal. First, the redundant computation caused by the full graph traversal. Second, whether the traversal is reasonable, which requires that each outgoing edge should be consistent with the real traffic scenario. Third, future trajectories of different vehicles can exhibit different kinematic characteristics, requiring the model to capture the multimodality of the trajectories. We refer to the idea of behavioral cloning27 to design a strategy network. The reachable nodes are filtered based on prior knowledge of the spatial location of the road before traversal, and in the traversal the kinematic features of the target vehicle, the local scene around it while it is travelling and the vehicle contextual features are taken into account, and the weight of the next node is dynamically adjusted using the principle that the human driver’s visual attention varies with the speed in order to compute the final node score. The strategy network uses this node information to output the discrete probability of each node, providing more explicit prediction conditions for the decoder.

According to the defined edge types, the target vehicle can move from the initial node along multiple directions such as succeeding edges, neighboring edges, etc. to explore routes in different directions. In order to consider the subjective internal driving needs and objective external constraints of the target vehicle, only nodes with edges from the target vehicle’s distance threshold are included, effectively avoiding indiscriminate treatment of all nodes. In addition, after the nodes in the lane graph are processed by the feature aggregation module, the nodes are coupled with the trajectory features of nearby traffic participants in addition to their own lane features. Therefore, the candidate strategies have the ability to generate multimodal trajectories at the same time. The outgoing edge scores of the nodes are computed as an evaluation mechanism for the candidate strategies in order to accurately quantify the selection of each decision point and clarify its deviation from the true trajectory. The scores are calculated based on the current node and nodes in the presence of successor and neighbouring edges, as well as the trajectory characteristics of the self-vehicle. The calculation of the node’s outgoing edge score relies on the dynamics of the target vehicle’s historical trajectory, and the road characteristics of the source and target nodes, formulated as:

During driving, the prefrontal lobe of the human brain plays a central role in decision making, while the parietal cortex is involved in spatial reasoning, helping drivers to judge position and distance35. However, in complex and highly dynamic environments, information from only a few external vehicles can be processed efficiently due to the limitations of the brain’s working memory36. To simulate this adaptive visual attention of human drivers, a speed-area dynamic adjustment method is introduced in the traversal process. This method differs from models that assume a uniform distribution of attention by adjusting the visual field according to the vehicle speed. Based on the official annotated statistics of the Nuscnes9 dataset and knowing the speed distribution of the dataset, we build a speed-dependent driving field of view range decay function such that the higher the speed, the field of view range weights gradually decay, i.e., the more attention is focused on the front; and widens at lower speeds for a wider peripheral field of view. In practice, the dynamic behavioral of the vehicle and the driving environment may lead to complex non-linear features in the relationship between speed and field of view. The logarithmic function part of the decay function is mainly used to simulate the initial trend of the view angle change with speed. And by introducing the polynomial P(v), this relationship can be described more comprehensively, leading to intuitive and context-sensitive trajectory prediction. The function is defined as follows:

First, the yaw angle \({\theta }_{i}\) of the i-th node with respect to the target vehicle needs to be calculated. speed is the current vehicle speed, and \({\theta \left(Speed\right)}_{max}\) is the maximum yaw angle at the current speed. Calculated using Eq. (9), we use a more moderate logarithmic function with a polynomial, so that the viewing angle decreases gently as the speed increases, but does not decrease too fast. Θ is a constant coefficient, and k is a parameter that adjusts the rate of contraction of the viewing angle. For example, the value of the logarithmic function at low speed is very small, which means that the maximum range of visual field at speed 0 is Θ, so \({\theta \left(Speed\right)}_{max}\) is close to \({\theta }_{0}\), and vice versa, the smaller the range of visual field is. After obtaining \({\theta \left(Speed\right)}_{max}\), we substitute it into the sigmoid function to calculate \(w_{\theta } \left( i \right) \in \left( {0, 0.5} \right)\), which is the visual field weight of the i-th node. The sigmoid function is chosen here to keep the values smooth and stable. Different \({w}_{\theta }\) corresponds to traversal weights for different reachable node directions. Finally, the previous score Score is dot-product with \({w}_{\theta }\) and normalised to probability by softmax function.

To avoid the computational redundancy associated with full graph traversal while maximising the retention of the majority of nodes to maintain multimodality, corresponding nodes with probability values less than \({P}_{TH}\) are no longer visited, as these nodes indicate a significant deviation from the main direction of travel or have a negligible impact on the prediction, and therefore do not substantially change the final route of travel.

This method enhances the model’s understanding of how attention is allocated during driving by dynamically adjusting weights based on vehicle speed. It allows for adaptive exploration of reachable nodes in changing driving environments, capturing crucial perceptual cues necessary for human-like accurate predictions. Consequently, the prediction model is equipped with beyond-line-of-sight, multimodal, and human-like predictive capabilities.

Counterfactual reasoning

The previous model was limited to feature fusion within the historical scene context. However, given the uncertainty of future scenes in trajectory prediction, we aim for the target vehicle to focus more on parts of the future scene that are related to the historical context. Here, the dependent variable \({C}_{t}\) changes to \({C}_{t+n}\), while the variable representing the target vehicle trajectory encoding remains unchanged. This aligns with the basic requirements of counterfactual reasoning techniques, which infer future trajectories in counterfactual scenes based on trajectory encoding in factual scenes. This is made possible by the future candidate nodes obtained through the node refinement strategy and their corresponding node encodings, along with the target vehicle’s motion encoding. After traversing the lane graph via the policy network, all nodes on the lane graph are sampled to obtain potential path nodes. The sampled lane graph nodes correspond to the node encodings described in Counterfactual reasoning section, as we need the encodings at the corresponding nodes to provide detailed semantic features (such as the motion state of vehicles near the node and the node’s own yaw angle). Subsequently, multi-head attention is employed to sample from different perspectives, resulting in more enriched feature information. In this process, 32 parallel attention heads are used, with the target vehicle’s motion encoding being linearly projected to obtain the queries, while node features are linearly projected to compute the keys and values for attention. Each head computes its attention simultaneously, and the results are concatenated. The output of the multi-head attention layer is a context vector \({V}_{C}\), which encodes the path.

The above process is crucial, as it not only serves as counterfactual reasoning but also acts as the final fusion process. After completing all these steps, the model acquires the top-level features of the target vehicle in the environment, which can then be passed to the decoder to output the prediction results.

Multimodal trajectory decoding

After the previous historical trajectory and road node coding, feature fusion and cognitive strategy module based on counterfactual inference, the final hidden feature vector is obtained and its individual target vehicle historical trajectory coding is spliced and mapped into the global context vector \({V}_{C}\) required for decoding. the hidden vector in the model graph is a Gaussian distributed random variable \({Z}_{k}\), the fusion coding \({\varepsilon }_{tar}\) is connected with the context vector \({V}_{C}\), so that the decoder can generate different motion contours. so that the decoder can generate different motion profiles. When designing the decoder network structure, only multimodal trajectories on future time steps are output using MLP in order to balance lightweight and efficiency.

The MLP consists of 2 linear layers stacked with hidden cell sizes 128 and 64 and an output dimension of 24. Candidate targets after node refinement are sampled to increase coverage of potential future locations using counterfactual inference techniques. The output is represented as \({\text{Traj}}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{B\times N\times 24}\), where B is the batch size, N is the number of samples, and 24 is the global coordinates predicted 6 s into the future at a frequency of 2 Hz. A large number of samples will have similar trajectories, and a K-mean algorithm is used to cluster the sampled trajectories to obtain a set of K representative predictions. The final output is represented as \(T\in {\mathbb{R}}^{B\times K\times 12\times 2}\), and the number of sets K can be adjusted by the specific needs of the trajectory decoder.

Loss functions

The output of the model consists of K trajectories. The loss function consists of a classification loss function and a regression loss, both of which are summed by weight.

In order to assign nodes to the target vehicle in a more rational way, the lane node that is closest to the vehicle and within the yaw angle threshold is assigned to the target vehicle. Therefore, the predicted trajectory of the target vehicle determines which edges are visited by the vehicle. Using the labelled values of all edges visited by the real trajectories, the cross-entropy loss is chosen as the loss function of the candidate policy, given by the following Eq. (15). In addition, the trajectory with the smallest average displacement error from the true trajectory among the K trajectories is used as the regression loss \(Los{s}_{reg}\) to ensure the diversity of trajectories. Huber loss is used to reduce the effect of outliers, which combines squared loss with absolute value loss. The formula is expressed as:

Experiments and analyses results

The experiments were conducted on the publicly available nuScenes dataset to train and validate the proposed method. We followed the official nuScenes guidelines to divide the dataset into training, validation, and test sets to ensure fairness in the experiments. The experiments were implemented using Python 3.9 and the PyTorch deep learning framework. The training was carried out on a server equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 3090 (24 GB) GPU. We used the Adam optimizer with a dynamic learning rate adjustment strategy. The initial learning rate was set to 0.001, and it was halved every 20 training epochs to implement gradual learning rate decay.

Evaluation indicators

The experiment uses standard evaluation metrics to measure prediction performance, including minFDEk, minADEk, and Miss Rate (MRk), which represent the final displacement error, average displacement error, and miss rate, respectively. All evaluation metrics are measured in meters, with lower values indicating higher accuracy.

-

1.

minFDEk denotes the L2 distance between the endpoints of the best of the k predicted trajectories and the ground truth.

$$\min FDE_{K} = min_{{{\text{i}} \in \left\{ {1,...,k} \right\}}} \left\| {Y^{GT} - Y^{t} } \right\|$$(17) -

2.

minADEk denotes the average L2 distance between the best of the k predicted trajectories and the ground truth.

$$MinADE_{K} = min_{{{\text{i}} \in \left\{ {1,...,k} \right\}}} \frac{1}{{T_{f} }}\sum\limits_{t = 1}^{{T_{f} }} {\sqrt {(Y^{GT} - Y^{t} )^{2} } }$$(18) -

3.

MRk measures the percentage of samples with a final error greater than 2 m.

Performance comparison and analysis

CCTP-Net is validated on the nuScenes dataset and compared with other methods to demonstrate the improvement in multimodal prediction accuracy of the proposed model. We chose different representative methods for comparative experiments. CoverNet12, Li37, and CASPNetv_238 use rasterized maps as input. The methods SG-Net35 and Trajectron++36 do not utilize map information. LaPred39 employs 1D CNN and LSTM to extract vehicle and road features and uses an attention mechanism for feature fusion. P2T39 applies inverse reinforcement learning on a 2D grid to obtain path and state rewards for generating multimodal trajectories. GoHome25 and THOMAS26 use graphs to represent road structures and vehicle trajectories, outputting the probabilities of future vehicle trajectories through heatmaps. Huang et al.22, PGP27, SocialFormer40, and Hu et al.31 adopt vectorized high-definition maps for prediction. Among them, Huang et al. utilized counterfactual reasoning to enhance model transparency, but the prediction accuracy was unsatisfactory. The results of the experiments are shown in Table 1.

The minADE and MR of two multimodal trajectories for K = 5 and K = 10 were evaluated in the comparison experiments. minADE and MR outperformed the other models. The FDE metric at K = 1 is evaluated, which still outperforms most models and ranks 2nd, indicating that better results can also be achieved in long time domain prediction. This is attributed to the interplay of the model’s multi-scale encoder, causal intervention on trajectories, and the node refinement strategy.

Ablation experiments

To assess the contribution of each component to the model’s performance, we designed and conducted ablation experiments. The goal of these experiments is to analyze the impact of different modules on overall performance by progressively removing or replacing them. Specifically, we conducted experiments on the encoder, multi-feature causality, policy module, and other network components in the model. We explored five different network structures in comparison to our model, using the same evaluation metrics for quantitative comparison, revealing the importance of each module in the model. The specific results are shown in Table 2.

The components in Encoder are replaced with individual GRU and Bi-GRU to obtain models M1 and M2. The experimental results show that the performance of the encoder using MSE is improved regardless of the combination with any other modules. This is due to the fact that MSE can obtain different granularity temporal dependencies from different time scales and provide temporal features for the subsequent feature aggregation stage.

In model M3, the causal intervention module was removed, and the input trajectory sequence was directly fed into the multi-scale encoder, bypassing the process of extracting spatial features from the road scene context. As a result, the model was unable to fairly learn the spatiotemporal representation of the trajectory, which negatively impacted performance. This result underscores the significance of scene context features in predicting complex scenarios and demonstrates the rationale and effectiveness of implementing causal interventions in trajectory prediction to avoid spurious correlations. In addition, we replace GAT with GCN in the Fusion stage to obtain model M4, and the results show that GAT is slightly better than GCN, which we believe is due to the introduction of the attention mechanism in GAT, which is able to dynamically learn the weights of different neighbours based on the specific relationships between nodes (e.g., vehicle positions, speeds, etc.), and adaptively focus on the neighbouring vehicles or road nodes that are more important for the future trajectory of the target vehicle, while ignoring those less relevant nodes while ignoring those less relevant parts.

In order to verify the usefulness of the proposed node refinement strategy for prediction, we replace the driving cognition-based traversal algorithm in the node refinement strategy with the full-graph traversal model M5 to comparatively demonstrate the impact of the node refinement strategy on the final prediction results. The results of the ablation experiments show that the driving cognition-based traversal algorithm significantly outperforms the full graph traversal approach. This is due to the fact that our method somewhat filters out nodes that have a negligible impact on the prediction, providing the decoder with a more accurate and fine-grained feature vector, which improves the prediction accuracy.

Hyperparametric experiments

For the hyperparameters in the experiment, we adjusted the perspective contraction rate parameter K and the threshold for filtering nodes, as shown in Fig. 5a.

We found that K = 2 to be the most stable choice, as it effectively adapted to both low-speed and medium–high-speed driving scenarios. This setting maintained a multimodal distribution of weights while ensuring that the focus remained on the forward area at higher speeds. When K = 1, the perspective contraction was too weak, causing the vehicle to still consider a large number of irrelevant nodes at high speeds. On the other hand, with K = 3, the perspective contracted more quickly, allowing for a certain node weight distribution at low speeds, but as the speed increased, the weights became overly concentrated on the forward nodes. In Fig. 5b, when \({P}_{TH}\)= 0.2 or 0.25, most nodes were retained, even if their final computed weights were relatively low. This setting was suitable for complex road scenarios, especially in low-speed or dense urban traffic environments, ensuring multimodality. However, when \({P}_{TH}\) = 0.3, 0.35, or 0.4, performance gradually declined as the majority of lower-weighted nodes were filtered out, leaving only a few nodes with the highest weights.

The lane graph is an important infrastructure for the model, and the experiments further conducted hyperparametric experiments on the resolution of the lane graph to test the effect of the node refinement strategy on the prediction results under different road resolutions. The experimental results are shown in Fig. 6. The minADE5 and MR5 have the lowest performance when using 20 m resolution. The prediction performance using 10 m and 15 m resolution is comparable. The best minADE5 metrics were obtained with the 10 m resolution, but MR5 was slightly inferior to the resolution at 15 m. The experimental results show that simply increasing the lane graph resolution does not significantly improve the predictive ability of the model. Although higher resolution data theoretically provides more detailed information, it also increases the complexity of the model. This is because the number of nodes constructing the lane graph increases linearly when higher resolution is used, thus expanding the computational requirements of the model parameters.

Computational performance analysis

Due to the adoption of a driver cognition-based node refinement strategy, redundant node calculations are reduced, thereby decreasing model training time and improving prediction inference speed. The proposed model completes training in just 7.6 h on a single NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU. In Table 3, a comparison is made with the target-driven method, DenseTNT24. Experimental results show that under the same conditions, this model requires 128 ms per batch for inference, reducing inference time by approximately 76% compared to DenseTNT. Additionally, inference speed is improved by about 55% compared to the model without using the candidate strategy, CCTP-Net. Compared to previous target-driven methods, CCTP-Net consumes fewer computational resources, thanks to our node feature refinement strategy. This further demonstrates that applying the human driving cognition process of speed-region adaptive changes to trajectory prediction enables the model to focus on the most relevant features when processing large amounts of complex scene context information, thus reducing unnecessary computational burden.

Visualisation and analysis of prediction results

We selected typical road scenarios such as intersections, junctions, and roundabouts from the nuScenes dataset and visualized the predicted outcomes for the target vehicle in these scenarios, as shown in Fig. 7. On the left, we display a bird’s-eye view of the actual driving scene, where the red vehicle represents the target vehicle, and the yellow vehicles represent surrounding obstacle vehicles. On the right, we show the predicted trajectories, where the red lines indicate the predicted trajectories of the target vehicle, and the green solid lines represent the actual trajectories. We set the multimodal trajectory prediction value K = 5, meaning five possible future trajectories were predicted.

Figure 7a shows the intersection scenario. The target vehicle is in the left turn lane of the intersection, and it is obvious that the prediction results give five correct trajectories, and the point with the highest probability is close to the real trajectory point of the target vehicle. Figure 7b shows the fork in the road scene. The yaw angle of the target vehicle has shown a tendency to turn right, and all five trajectories predicted by the model are chosen to turn right. The results show that the predicted trajectories are in line with human drivers’ habits. The model does not give a straight ahead route, which is due to the fact that only points with concentrated relative yaw angles are considered in our strategy, indicating that the predictive model is highly anthropomorphic. Figure 7c shows the slow straight ahead road condition with traffic jam, the model is able to capture the characteristic of slow speed of congested road vehicles and therefore gives a trajectory with relatively slow speed. Figure 7d is the fork in the road scene. The yaw angle of the target vehicle no longer shows a left-turn trend and there is a vehicle ahead, still a left-turn trajectory is predicted without losing the multimodal and is an avoidance of the car in front of it, thanks to the node refinement of the anthropomorphic approach to the learning of real driving behaviour. Figure 7e shows a roundabout scenario, where the target vehicle is travelling in the inner lane of the roundabout, and it can be estimated that the target vehicle is driving along the first exit ahead, or the second exit, where 4 indicate the first exit, and the prediction result is close to the real trajectory. Figure 7f shows a faster scene faster one, where it is clear that the trajectory extends longer and shows the behaviour of overtaking more than one vehicle ahead. Figure 7f is different from the scene in Fig. 7a, in which the target vehicle is travelling straight ahead, the vehicles on the left side of the intersection are stopped at the red light, and pedestrians are passing on the zebra crossing on the right side. The target vehicle quickly passes through the intersection and makes a driving strategy adjustment to change lanes to overtake in response to the vehicle in front of it.

In order to have a more intuitive understanding of the key role of the node refinement strategy in the model, we trained a model that did not use the node refinement strategy. In the same scenario, the left figure is used and the right figure is not used. As shown in Fig. 8a, the strong topological constraints of the lane graph itself are utilized to capture the nodes where road vehicles’ attention is highly focused and combined with the corresponding nodes of the spatio-temporal causal encoding, so as to focus on the node features that are useful for the prediction itself. Comparison results show that Fig. 8b provides distinctly differentiated five trajectories, but in fact, these multimodal trajectories are not very sensible on because the real trajectory is left turn, while the predicted more trajectories deviate severely from the vehicle’s movement trend and future. The phenomenon resonates with the attentional properties of human drivers. To further validate this idea, we randomly visualized 50 traffic scenarios and observed an interesting pattern: during graph traversal, using an overly broad observation range reduced prediction performance. On the other hand, adaptively focusing on road nodes within the vehicle’s field of view, based on its speed, improved performance. This observation highlights a key challenge in current multi-feature fusion methods—how to effectively distinguish the importance of relevant information in a targeted manner.

CCTP-Net demonstrates high compatibility and multimodal alignment with the real future trajectories of vehicles across various complex traffic scenarios, including crossroads, turnoffs, straight roads, and multi-vehicle slow-moving traffic. The model incorporates multiple influencing factors, such as lane structure, inter-vehicle interactions, kinematic features, and driver cognitive characteristics, while emphasizing the significance of scenario context information in trajectory prediction through causal inference. By accounting for the strong constraints imposed by road topology and multimodal behavior, CCTP-Net effectively captures potential variations in vehicle speed, thereby enhancing prediction accuracy. This improvement is critical for decision-making and path planning in the downstream systems of intelligent connected vehicles.

Limitations

During the visualization process, we observed that the model has certain limitations in complex scenarios with low traffic participant volume and slower vehicle speeds. Specifically, as shown in Fig. 9, when vehicles are faced with a high-dynamic scenario involving low-speed tailgating and multiple vehicles intersecting, the predicted trajectories, although not deviating from the actual driving direction, exhibit varied longitudinal speed responses in the multimodal predictions. However, there is a lack of sufficient lateral multimodal transitions. This subtle deviation mainly stems from differences in the cognitive representation of the driver’s lateral decision-making in specific traffic environments. Therefore, there is still significant room for improvement in human cognition models in high-dynamic scenarios, which provides an important direction for future research, such as optimizing the model with richer driving data or incorporating personalized modeling.

Conclusion

This paper proposes an intelligent connected vehicle trajectory prediction model, CCTP-Net, designed to accurately and reasonably predict vehicle trajectories in complex road environments. Based on causal reasoning theory, the model employs causal intervention and counterfactual reasoning to mitigate the impact of spurious correlations caused by specific trajectories. To further enhance prediction performance, a novel node refinement strategy is introduced between feature aggregation and the decoder. This strategy incorporates driver cognition characteristics to traverse and filter nodes in the lane graph, generating refined feature vectors for the decoder.

Experimental results demonstrate that CCTP-Net performs exceptionally well in multimodal trajectory prediction tasks and achieves satisfactory results on the challenging urban road scenario dataset, nuScenes. Notably, the node refinement strategy, which leverages driver cognition characteristics, significantly improves prediction accuracy, offering an effective solution for trajectory prediction in complex traffic environments. While this study primarily focuses on trajectory prediction for intelligent connected vehicles (ICVs), we believe that similar approaches have the potential to advance research on causal relationships and multi-feature fusion in other autonomous driving tasks, paving the way for broader applications.

Despite its significant contributions, this study has certain limitations that require further exploration. For instance, the current model is designed to predict the trajectory of a single target vehicle, lacking the capability to jointly predict the trajectories of all vehicles in a traffic scene. This restricts its applicability in more complex scenarios. Future research will focus on the following directions: (1) Expanding the model’s predictive capabilities to simultaneously forecast the trajectories of multiple targets in a single traffic scene while effectively capturing dynamic interactions among multiple agents. (2) Further exploring the application of causal reasoning in other autonomous driving tasks, such as multimodal data fusion and decision-making optimization. Through these improvements, we aim to provide more comprehensive and efficient solutions for trajectory prediction in complex traffic scenarios.

Data availability

Data related to this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Huang, Y. et al. A survey on trajectory-prediction methods for autonomous driving. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 7(3), 652–674. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIV.2022.3167103 (2022).

Gao, J. et al. VectorNet: Encoding HD maps and agent dynamics from vectorized representation. In 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 11525–11533. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.01154 (2020).

Liang, M. et al. Learning lane graph representations for motion forecasting. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference (ECCV) 541–556. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58536-5_32 (2020).

Feng, C. et al. MacFormer: Map-agent coupled transformer for real-time and robust trajectory prediction. IEEE Rob. Autom. Lett. 8(10), 6795–6802. https://doi.org/10.1109/LRA.2023.3311351 (2023).

Mo, X., Liu, H., Huang, Z., Li, X. & Lv, C. Map-adaptive multimodal trajectory prediction using hierarchical graph neural networks. IEEE Rob. Autom. Lett. 8(6), 3685–3692. https://doi.org/10.1109/LRA.2023.3270739 (2023).

Zhao, H. et al. TNT: Target-driven trajectory prediction. In Conference on Robot Learning 895–904. (2021)

Liao, H. et al. A cognitive-based trajectory prediction approach for autonomous driving. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 9(4), 4632–4643. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIV.2024.3376074 (2024).

Tucker, A. & Marsh, K. L. Speeding through the pandemic: Perceptual and psychological factors associated with speeding during the COVID-19 stay-at-home period. Accid. Anal. Prev. 159, 106225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2021.106225 (2021).

Caesar, H. et al. Nuscenes: A multimodal dataset for autonomous driving. In 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 11621–11631. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.01164 (2020).

Wang, Z., Zhang, J., Chen, J. & Zhang, H. Spatio-temporal context graph transformer design for map-free multi-agent trajectory prediction. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 9(1), 1369–1381. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIV.2023.3329885 (2023).

Liao, H. et al. MFTraj: Map-free, behavior-driven trajectory prediction for autonomous driving. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.01266 (2024).

Phan-Minh, T., Grigore, E. C., Boulton, F. A., Beijbom, O., & Wolff, E. M. CoverNet: Multimodal behavior prediction using trajectory sets. In 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 14074–14083. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.01408 (2020).

Xu, P., Hayet, J. B. & Karamouzas, I. Context-aware timewise VAES for real-time vehicle trajectory prediction. IEEE Rob. Autom. Lett. 8, 5440–5447. https://doi.org/10.1109/LRA.2023.3295990 (2023).

Gu, X., Song, G., Gilitschenski, I., Pavone, M., & Ivanovic, B. Accelerating online mapping and behavior prediction via direct BEV feature attention. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.06683v1 (2024).

Yuan, T., Liu, Y., Wang, Y., Wang, Y., & Zhao, H. StreamMapNet: Streaming mapping network for vectorized online HD map construction. In 2024 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV) 7356–7365. https://doi.org/10.1109/WACV57701.2024.00719 (2024).

Ding, W., Qiao, L., Qiu, X., & Zhang, C. PivotNet: Vectorized pivot learning for end-to-end HD map construction. In 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) 3672–3682. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV51070.2023.00340 (2023).

Li, S., Li, J., Meng, Q., Guo, H. & Cao, D. Multi-interaction trajectory prediction method with serial attention patterns for intelligent vehicles. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 73(6), 7517–7531. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2024.3349601 (2024).

Liu, M. et al. LAformer: Trajectory prediction for autonomous driving with lane-aware scene constraints. In 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW) 2039–2049. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPRW63382.2024.00209 (2024).

Ngiam, J. et al. Scene transformer: A unified architecture for predicting multiple agent trajectories. https://arxiv.org/abs/2106.08417 (2021).

Yao, L. et al. A survey on causal inference. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data 15(5), 1–46. https://doi.org/10.1145/3444944 (2021).

Li, J., Li, H., Liu, J., Zou, Z., Ye, X., Wang, F. et al. Exploring the causality of end-to-end autonomous driving. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.06546v2 (2024).

Huang, Y., Wang, F., & Zhu, T. Prediction of traffic participant behavior in driving environment based on counterfactual inference. In International Conference on Autonomous Unmanned Systems 499–510. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-97-1087-4_47 (2023).

Liu, J. et al. Reliable trajectory prediction in scene fusion based on spatio-temporal structure causal model. Inf. Fusion. 107, 102309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2024.102309 (2024).

Gu, J., Sun, C., & Zhao, H. DenseTNT: End-to-end trajectory prediction from dense goal sets. In 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) 15303–15312. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.01502 (2021).

Gilles, T., Sabatini, S., Tsishkou, D., Stanciulescu, B., & Moutarde, F. Gohome: Graph-oriented heatmap output for future motion estimation. In 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA) 9107–9114. https://doi.org/10.1109/icra46639.2022.9812253 (2022).

Gilles, T., Sabatini, S., Tsishkou, D., Stanciulescu, B., & Moutarde, F. Thomas: Trajectory heatmap output with learned multi-agent sampling. https://arxiv.org/abs/2110.06607 (2021).

Deo, N., Wolff, E., & Beijbom, O. Multimodal trajectory prediction conditioned on lane-graph traversals. In Conference on Robot Learning 203–212 (2022).

Varadarajan, B. et al. Multipath++: Efficient information fusion and trajectory aggregation for behavior prediction. In 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA) 7814–7821. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICRA46639.2022.9812107 (2022).

Zhong, Y., Ni, Z., Chen, S., & Neumann, U. Aware of the history: Trajectory forecasting with the local behavior data. In European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV) 393–409 (2022).

Lu, Y., Yang, F. & Li, X. Vehicle trajectory prediction model for unseen domain based on the invariance principle. In 2024 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV) 788–794 (2024).

Hu, H. et al. A hybrid data-driven and mechanism-based method for vehicle trajectory prediction. Control Theory Technol. 21(3), 301–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11768-023-00170-x (2023).

Liao. H. et al. BAT: Behavior-aware human-like trajectory prediction for autonomous driving. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 10332–10340. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v38i9.28900 (2024).

Veličković, P., Cucurull, G., Casanova, A., Romero, A., Liò, P., & Bengio, Y. Graph attention networks. In International Conference on Learning Representations. https://openreview.net/forum?id=rJXMpikCZ (2018).

Lin, Z. et al. RCBEVDet: Radar-camera fusion in Bird’s eye view for 3D object detection. In 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 14928–14937. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR52733.2024.01414 (2024).

Miyamoto, K. et al. Identification and disruption of a neural mechanism for accumulating prospective metacognitive information prior to decision-making. Neuron 109(8), 1396–1408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2021.02.024 (2021).

Loke, S. W. Cooperative automated vehicles: A review of opportunities and challenges in socially intelligent vehicles beyond networking. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh 4(4), 509–518. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIV.2023.3275164 (2019).

Li, L. et al. Real-time heterogeneous road-agents trajectory prediction using hierarchical convolutional networks and multi-task learning. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 9(2), 4055–4069. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIV.2023.3275164 (2023).

Schäfer, M., Zhao, K., Bühren, M., & Kummert, A. Context-aware scene prediction network (CASPNet). In 2022 IEEE 25th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC) 3970–3977. https://doi.org/10.1109/ITSC55140.2022.9921850 (2022).

Kim, B. et al. LaPred: Lane-aware prediction of multi-modal future trajectories of dynamic agents. In 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 14636–14645. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR46437.2021.01440 (2021).

Wang, Z., Sun, Z., Luettin, J., & Halilaj, L. Social former: Social interaction modeling with edge-enhanced heterogeneous graph transformers for trajectory prediction. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.03809 (2024).

Wang, C., Wang, Y., Xu, M. & Crandall, D. J. Stepwise goal-driven networks for trajectory prediction. IEEE Rob. Autom. Lett. 7(2), 2716–2723. https://doi.org/10.1109/LRA.2022.3145090 (2022).

Deo, N., & Trivedi, M. M. Convolutional social pooling for vehicle trajectory prediction. In 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW) 1468–1476. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPRW.2018.00196 (2018).

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing, China (cstc2021ycjh-bgzxm0088), the Science and Technology Research Project of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission, China (KJZD-M202303401), and the Program for Innovation Research Groups at Institutions of Higher Education in Chongqing (CXQT21032). Additionally, we acknowledge the support from the Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (Grant No. KJZD-M202203401, KJQN202403401). Their contributions have been invaluable in facilitating this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhiyong Yang and Jun Yang (Co-first authors): Contributed equally to the research conception, framework design, integration of causal reasoning and driving cognition into the trajectory prediction model, and led the experimental design and implementation. Yu Zhou: Conducted data analysis, evaluated model performance, proposed improvements, and assisted in interpreting results. Qinxin Xu: Set up the experimental environment, processed data, provided technical support, and optimized the model. Minghui Ou: Assisted with the literature review, organized related work, contributed to writing, and revised the manuscript for completeness and coherence.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Z., Yang, J., Zhou, Y. et al. Multimodal trajectory prediction for intelligent connected vehicles in complex road scenarios based on causal reasoning and driving cognition characteristics. Sci Rep 15, 7259 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91818-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91818-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

ChatMPC: a language-driven model predictive control framework for adaptive and personalized autonomous driving

Autonomous Intelligent Systems (2025)