Abstract

This paper studied the relationship and mechanisms of parent–child relationship, interpersonal relationship on campus, academic self-efficacy and academic burnout among adolescents. A study of 913 Chinese junior high school students from Fujian province (47.20% males, mean age = 13.99 years, SD = 0.81) was conducted using the Junior Middle School Students’ Learning Weariness Scale, the Chinese version of parent–child affinity scale, the Loso Wellbeing Questionnaire, and the Academic Self-efficacy Questionnaire. (1) Academic burnout was negatively and significantly correlated with parent–child relationship (r = − 0.13, p < 0.01), interpersonal relationship on campus (r = − 0.11, p < 0.01), and academic self-efficacy (r = − 0.13, p < 0.01). Parent–child relationship was positively and significantly correlated with interpersonal relationship on campus (r = 0.23, p < 0.01) and academic self-efficacy (r = 0.38, p < 0.01). Interpersonal relationship and academic self-efficacy were positively and significantly correlated (r = 0.29, p < 0.01). (2) Parent–child relationship can significantly and negatively predicte academic burnout (β = − 0.082, p < 0.05). (3) Parent–child relationship affected academic burnout of adolescents via three significant indirect effects: the single mediating effect of interpersonal relationship on campus (effect = − 0.011) and academic self-efficacy (effect = − 0.019), and the chain mediating effect of interpersonal relationship on campus and academic self-efficacy (effect = − 0.003). Stronger parent–child relationship predicts lower levels of academic burnout. Moreover, parent–child relationship can indirectly affect academic burnout not only through the single mediating effect of interpersonal relationship on campus and academic self-efficacy but also through the chain mediating effect of interpersonal relationship on campus and academic self-efficacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the phenomena of academic burnout has become more and more prevalent among Chinese students. They are often stressed by heavy academic workload, high academic expectation from parents, dissatisfaction with their grades1, fierce academic competition2,3, and so on, which may lead to their study-weariness/academic tiresome. Academic tiresome is a continuous and dynamically developing spectrum involving cognition, emotion and behavior4,5. In Western cultures, academic tiresome is often expressed as “academic burnout”. Dimensions of academic burnout is highly similar to academic tiresome, and the measurements of academic burnout is almost identical to academic tiresome6. Academic burnout is a negative, learning-related, and persistent psychological state that mostly occurs among students7. Students who suffer from academic burnout typically display emotional exhaustion, decline in grades, lack of motivation to study, and refusal to go to school8,9. Previous research has shown that 46% of Chinese students lacked motivation of learning, 33% of Chinese students hated learning, and only 21% of Chinese students showed positive attitudes towards learning10. Among adolescent learners, the issue of academic burnout is even more widespread. According to the Annual Report on the Care of the Next Generation in China (2020), more than 70% of adolescent students suffered from academic burnout11. Another recent research among Chinese students had similar results, specifically, 63.6% of them experienced mediate levels of academic burnout and 10.7% of them experienced high levels of academic burnout8. Academic burnout not only causes psychological distress of students but also brings a series of potential negative consequences, such as poor academic performance, truancy, drop out of school, and even mental disorders12. Thus, in order to intervene such negative psychological state and improve adolescent students’ well-beings and learning motivation, it’s critical to investigate the protective factors against academic burnout and understand how they may reduce levels of academic burnout.

Bronfenbrenner proposed the biological ecosystem theory in 1979. He argued that human development is shaped by the individual’s interactions with complex multilevel dynamic socioecological systems, including microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem and chronosystem. Microsystem refers to the direct environment of individual activities and interactions, which is constantly changing and developing, and is the innermost layer of the environmental system. For most infants, the microsystem is limited to the family. In this perspective, the parent–child relationship in the family is seen as a key factor in the microsystem, with far-reaching implications for children’s mental health and development13. Attachment theory also indicates that the quality of an individual’s early parent–child relationship can lay the foundation for the healthy development of emotional regulation and social functions. Secure attachment relationships enable individuals to obtain psychological support and emotional security in unfamiliar or challenging situations, thereby enhancing self-confidence and problem-solving abilities14. Some studies have shown that good parent–child attachment can reduce adolescents’ problem behaviors and promote their social competence15. As infants continue to grow, their scope of activities expands constantly, and kindergartens, schools and peer relationships are gradually incorporated into their microsystems. For adolescents, school is the microsystem that has the greatest influence on them apart from the family16. The teacher–student relationship also provides positive feedback and learning guidance to support students in coping with academic challenges. This external assistance in task completion is an important way to enhance the sense of control and reduce the feeling of helplessness17. Research has shown that supportive behaviors of teachers (such as providing learning guidance and positive feedback) can enhance students’ interest in the classroom and their pursuit of social responsibility goals18. Existing literature also suggests that academic burnout can be affected by various external and internal factors, including family support, school support, self-efficacy, needs and motivations19,20. Subsequent researches have further examined specific external and internal factors, such as parent–child relationship, interpersonal relationship on campus and academic self-efficacy.

Parent–child relationship and academic burnout

The family can be a factor of positive or, conversely, negative influence on the upbringing of the child21. Parent–child relationship is a bidirectional and co-constructed relationship between parent and child, and it’s crucial to child’s physical, emotional, and social development22. When adolescents maintain good relationship with their parents, they typically have higher levels of resilience23, meaning that they can better handle adversity. For instance, substantial studies have found the association between parent–child relationship and academic burnout. Results of He’s survey study24 showed that parent–child conflict can positively predict academic burnout, implying that lacking a harmonious relationship with parents may lead to a higher level of academic burnout. Similarly, in a South Korean sample, adolescents reporting the optimal bonding parental style had lower levels of academic burnout25. The above findings have highlighted the role of parent–child relationship in academic burnout.

Mediating effect of interpersonal relationship on campus

While some researchers studied the factors in students’ family environment, other researchers focused on the factors in students’ school environment and investigated their interpersonal relationship on campus. Interpersonal relationship on campus primary includes teacher and peer relationships26. Ma et al.27 conducted a survey study among 2620 junior high school students and revealed the significant negative predictive effect of school interpersonal relationship on academic burnout. Maintaining good interpersonal relationship at school is important to adolescents’ campus life, implying that they can gain more social supports from teachers and peers. A meta-analysis of 19 studies showed that social supports from teachers and peers had a significant negative relationship with student burnout. On the other hand, interpersonal isolation at school, is significantly linked to hidden dropout12. The association between interpersonal relationship on campus and academic burnout is evident. As mentioned before, parents are key to the development of child’s social competency. Empirical research showed that perceived parent–child relationship involved parental admiration had a strong and positive association with peer acceptance of adolescents across cultures28. Therefore, a high-quality parent–child relationship may help adolescents improve their interpersonal relationship at school, and subsequently relief the negative effect of academic burnout. Interpersonal relationship on campus of adolescents may act as a mediating factor in the relationship between parent–child relationship and academic burnout.

Chain mediating effect of interpersonal relationship on campus and academic self-efficacy

Internal factors of students related to academic burnout have also been examined, for example, academic self-efficacy. Academic self-efficacy is defined as the perceived capabilities to learn or perform actions in academic settings29. The Self-Determination Theory proposed by Deci and Ryan identifies three basic types of motivation: intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and the state of no motivation. Self-efficacy effectively avoids the emergence of the state of no motivation by enhancing intrinsic motivation and viewing learning tasks as a means for personal growth. That is, people with high self-efficacy are more inclined to participate in learning due to the tasks themselves rather than external pressure, thereby reducing the probability of developing a dislike for learning30,31,32. Empirical research also supports that high levels of academic self-efficacy are beneficial to students, such that higher academic self-efficacy significantly predicting better academic performance of adolescents33. Moreover, high levels of academic self-efficacy are correlated with lower levels of academic burnout34. Academic self-efficacy may be influenced by parent–child relationship. In a study of academic performance, it was found that parent–child relationships were significantly and positively correlated with self-efficacy among Asian Americans35. Thus, a high-quality parent–child relationship may also help adolescents establish their academic self-efficacy, and consequently ease the negative impact of academic burnout. It was expected that academic self-efficacy of adolescents may mediate the effect of parent–child relationship on academic burnout. Moreover, academic self-efficacy is also affected by students’ interpersonal relationship at school. Positive teacher relationship improves students’ academic self-efficacy through increasing their learning motivation36,37. Positive peer relationship also facilitates students to form positive academic self-concept38. Based on the above researches, we hypothesize that the interpersonal relationships on campus and academic self-efficacy have a chain mediating effect between the parent–child relationship and academic burnout.

In summary, this study aims to explore the relationship and mechanism between parent–child relationship, interpersonal relationship on campus, academic self-efficacy and academic burnout among adolescents, hoping to provide new ideas and theoretical basis for improving academic burnout among adolescents.

Methods

Participants

The whole-group sampling method was adopted, and participants were recruited through contacting four junior high schools in Fujian Province, China. Participation of the study was voluntary and the questionnaires were anonymous. Only gender and age information were requested. Between February 1st and April 30th in 2024, paper questionnaires were distributed. A total of 1014 questionnaires were distributed and all were recovered. Among them, 201 questionnaires were excluded from the analysis due to their low response rate of the survey or consistent responses, and the valid rate was 90.04%. The final sample consisted 913 junior high school students (431 males, 482 females) aged 13 to 15 (13.99 ± 0.81). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University (Approval No.: MRCTA, ECFAH of FMU [2023]410). All participants and their parents signed written informed consents prior to the study.

Measures

Academic burnout

The Junior Middle School Students’ Learning Weariness Scale5 was used to measure adolescents’ academic burnout. The questionnaire includes three dimensions, including academic burnout cognition (seven items), academic burnout emotion (six items), and academic burnout behavior (four items). Participants were asked to rate each item with options ranging from 1 (not true at all) to 5 (extremely true). The higher summed scores across 17 items indicated a higher level of academic burnout. The analysis demonstrated sufficient internal reliability of the scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.70).

Parent–child relationship

The Chinese version of Parent-Child Affinity Scale39 derived from the Family Adaptation and Cohesion Evaluation Scale II (FACES II) was adopted to measure adolescents’ relationship with their parents. This scale consisted of 20 items, including 10 items describing the relationship between father and child, and 10 items describing the relationship between mother and child. Each item followed by five responses ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). Scores on 20 items were summed, and the higher total scores illustrated a higher quality of parent–child relationship. Current analysis suggested good internal reliability of the scale, with Cronbach’s α of 0.72.

Interpersonal relationship on campus

The measurement of interpersonal relationship on campus was adapted from the Loso Wellbeing Questionnaire26,40. There were two dimensions of this scale, social integration in the class (10 items, e.g., ‘I quite easily make friends at school’) and relationship with teachers (10 items, e.g., ‘I feel at ease with most of the teachers’). Each item had four responses, ranging from 1 (not true at all) to 4 (extremely true). A higher total score suggested a higher quality of interpersonal relationship. The Cronbach’s α of the scale was 0.70.

Academic self-efficacy

This variable was measured using the Academic Self-Efficacy Questionnaire from Liang41. This scale consisted of two dimensions, which were learning ability efficacy (11 items) and learning behavioral efficacy (11 items). Learning ability efficacy refers to the individual’s judgment and confidence on whether he has the ability to successfully complete his studies, get good grades and avoid academic failure, and learning behavioral efficacy refers to the individual’s judgment and confidence in their ability to employ specific learning strategies to reach their learning objectives. Responses were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not true at all) to 5 (extremely true). The higher total score, the greater sense of self-efficacy. The scale demonstrated high internal reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.84.

Data analysis

The analysis was conducted based on the empirical data provided by participants. SPSS version 27 was used for preliminary data processing, descriptive statistics, and the reliability and correlation analyses among the variables. Harman’s one-way test was performed to test the potential common method bias. If the percentage of variance explained for the first common factor is less than 40%, it can be considered that there is no significant common method bias in the present study42. In order to test the chain mediation effect, Model 6 in SPSS macro program process v3.3 developed by Hayes and Scharkow43 was used. Bootstrap method (5000 replicate samples with confidence interval set to 95%) was used to test the significance of the mediation effect.

Results

Common method bias test

As the current study adopted self-reported data from participants, there might be common method bias. The Harman’s one-way test was used to spot the possible common method bias. Results showed that there were 22 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1. The first principal component explained 16.49% of the total variance, which was below the critical value of 40%. This suggested that the common method bias had insignificant influence on the results of this study.

Correlation analysis

Pearson correlation was used to analyze the correlations of the major study variables. The results illustrated in Table 1 showed that academic burnout was negatively correlated with parent–child relationship (r = − 0.13, p < 0.01), interpersonal relationship on campus (r = − 0.11, p < 0.01) and academic self-efficacy (r = − 0.13, p < 0.01) respectively. Parent–child relationship was positively correlated with interpersonal relationship on campus (r = 0.23, p < 0.01) and academic self-efficacy (r = 0.38, p < 0.01). And interpersonal relationship on campus was positively correlated with academic self-efficacy (r = 0.29, p < 0.01). The age and gender have no correlation with the study variables (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 ).

Mediation effect test

The regression analysis results of the relationship between parent–child relationship and academic burnout are presented in Table 2. Parent–child relationship had a significant positive predictive effect on interpersonal relationship on campus (β = 0.233, p < 0.001). When parent–child relationship and interpersonal relationship on campus were included in the equation to predict academic self-efficacy, both variables positively predicted academic self-efficacy (β = 0.328, p < 0.001; β = 0.216, p < 0.001). When parent–child relationship, interpersonal relationship on campus and academic self-efficacy were included in the equation to predict academic burnout, both parent–child relationship and academic self-efficacy negatively predicted academic burnout (β = − 0.082, p < 0.05; β = − 0.077, p < 0.05), whereas interpersonal relationship on campus did not significantly predict academic burnout.

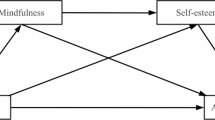

Table 3 shows the mediating effect value of interpersonal relationship on campus and academic self-efficacy between parent–child relationship and academic burnout. Figure 1 is a chain mediation model which shows the effects of parent–child relationship, interpersonal relationship on campus, and academic self-efficacy on academic burnout. Table 3 and Fig. 1 illustrated that interpersonal relationship on campus and academic self-efficacy played a significant mediating role between parent–child relationship and academic burnout, and the total standardized mediating effect value was − 0.0334. The mediating effect was composed of three indirect effects, including indirect effect 1: parent–child relationship → interpersonal relationship on campus → academic burnout (β = − 0.011, 95% CI − 0.0244, − 0.0002); indirect effect 2: parent–child relationship → academic self-efficacy → academic burnout (β = − 0.019, 95% CI − 0.0386, − 0.0014); and indirect effect 3: parent–child relationship → interpersonal relationship on campus → academic self-efficacy → academic burnout (β = − 0.003, 95% CI − 0.0067, − 0.0002). The ratios of the three indirect effects to the total effect were 11.69%, 20.04%, and 3.13% for indirect effect 1, 2, and 3. Moreover, the 95% confidence interval of the above indirect effect does not contain the zero value, meaning that all three indirect effects are significant.

Discussion

Results of the present study demonstrate that the single mediating effect of interpersonal relationship on campus and academic self-efficacy, and the chain mediating effect of interpersonal relationship on campus and academic self-efficacy help to explain the relationship between parent–child relationship and academic burnout among Chinese adolescent. First of all, it was found that parent–child relationship could significantly and negatively predicted the academic burnout of Chinese adolescents, such that when the parent–child relationship was stronger, the academic burnout level was lower. This finding is consistent with previous research evidence36, and illustrates that parent–child relationship is an important protective factor against academic burnout in the Chinese context. Previously, a study suggested that a good parent–child relationship help to promote adolescents’ resilience23, meaning that individuals with a good relationship with parents can better adjust themselves when facing challenges in life or at schools. Overall, there is no doubt that strong, healthy parent–child bonds help adolescents reduce levels of study-weariness.

Even though prior studies determined that parent–child relationship plays an import role in reducing levels of academic burnout, its underlying mechanism is not clear. Thus, this study tested the mediating effects of two relevant factors, which were interpersonal relationship on campus and academic self-efficacy. In line with our hypothesis, the significant mediating effect of interpersonal relationships on campus on the relationship between parent–child relationship and academic burnout was found. When students enter the stage of adolescence, they tend to seek support from peers to fulfill their needs of relatedness, and this has proven to be important to their life satisfaction and psychological well-beings26,44. Besides peer relationships, relationships with teachers also plays an important role in adolescents’ academic life. Students benefit from positive teacher relationships by not only gaining more academic support45 but also enhancing their sense of school connectedness46. School connectedness refers to the emotional connection between an individual and the people in the school environment, reflecting students’ sense of belonging and identity to the school and their perception of being cared for, recognized and supported47. Having good interpersonal relationships on campus plays an important role in adolescents’ school connectedness. Interpersonal relationship at school is affected by family related factors, in particular, adolescents’ relationship with their parents. High levels of closeness with parents were related to better interpersonal character of children which, in turn, is associated with peer acceptance48. It is clear that interpersonal relationship on campus is able to act as the mediator in the relationship between parent–child relationship and academic burnout. The single mediating effect of interpersonal relationship in this study is relatable to Chen’s prior finding36, where school connectedness mediated the effect of parent–child relationship on academic burnout.

The mediating effect of academic self-efficacy on the relationship between parent–child relationship and academic burnout was significant in this study, accounting for the highest ratio of the total indirect effect (20.04%). This result shows that highlights the importance of academic self-efficacy for adolescents who experience academic burnout. Compared to the single mediating effect of interpersonal relationship on campus, the single mediating effect is stronger. Besides, the results of regression analysis showed that interpersonal relationship on campus did not significantly predict academic burnout. These results may be due to that academic pressure was considered to be a major source of stress for students in Asian countries19, where may be a more competitive academic environment49. And when adolescent students are pressured by the heavy academic workload and the difficulty of curricula at middle school, they may allocate less time and effort in making connections with others on campus. As adolescents pay a lot of attention to their academic performance, having the self-concept and belief that they are competent to deal with academic tasks is more closely associated with academic burnout. In addition, the influence of interpersonal relationships on campus on academic burnout may depend on other factors, such as personality traits, stress levels, or cultural norms. For example, introverted students may be less affected by interpersonal relationships on campus. This might explain why, in this study, interpersonal relationships on campus failed to significantly predict academic burnout.

A significant chain mediating effect of interpersonal relationship on campus and academic self-efficacy was found, however, it accounted for the lowest ratio of the total indirect effect (3.13%). Although both interpersonal relationship on campus and academic self-efficacy were recognized as mediators in the relationship between parent–child relationship and academic burnout, and the correlation between interpersonal relationship on campus and academic self-efficacy was found in current and prior study26, we should put in mind that academic burnout is a complex spectrum involving cognition, emotion and behavior that may influenced by many other internal and external factors. In order to better examine the mechanism underlying the relationship between parent–child relationship and academic burnout, future study should consider control potential influential variables such as culture and value of family, parenting styles, social economic status, as well as personality and interpersonal character of adolescents.

Implications

This study reveals that parent–child relationship, interpersonal relationship on campus and academic self-efficacy are not only important protective factors for academic burnout, but also act on academic burnout through a single mediating effect and a chain mediating effect. This finding further enriches the theoretical framework for the influencing factors of academic burnout, especially its applicability in the context of Chinese culture, and provides theoretical support for cross-cultural research. Meanwhile, it reveals the core role of parent–child relationship, which provides a theoretical basis for subsequent research and emphasizes the core position of families in adolescent psychology. The bioecological systems theory emphasizes that individuals are affected by multi-level dynamic social ecosystems. This study also verified the effect of key factors (parent–child relationships and interpersonal relationship on campus) in microsystems (family and school) on academic burnout in adolescents through empirical data, supporting the applicability of this theory in explaining adolescent mental health and academic behavior.

In terms of practice, it helps to put forward intervention strategies against academic burnout. Firstly, priority should be given to parent–child relationship intervention. Parent classes can be implemented, teaching them communicating skills and other parenting knowledge. Secondly, school activities can be planned to facilitate positive interactions between teachers, peers and students such that they will have more chances to further develop friendly interpersonal relationships. Thirdly, schools should reduce academic competitions among students, foster goal settings, provide frequent, detailed and positive feedback, and maintain a cooperative learning atmosphere to promote students’ academic self-efficacy.

Limitations

This study has made a contribution to understanding the mechanism of how parent–child relationship affects academic burnout among adolescents. However, our data was based on a sample from Southeast China, so the results probably could not be directly generalized to populations in other regions or countries. In addition, the study was cross-sectional, and it’s possible that these effects could change over time. We have also noticed that the internal reliability of scales measuring academic burnout, parent–child relationship and interpersonal relationship on campus was 0.70 to 0.72. Such internal reliability is considered acceptable in general, and considering these scales have been shown to have good internal consistency in previous studies and have been widely used5,26,39,50,51,52. Therefore, these scales were still used in this study. Last but not the least, the above results cannot help us draw causal conclusions.

Conclusion

Parent–child relationship, interpersonal relationship on campus and academic self-efficacy are protective factors against academic burnout. Stronger parent–child relationship predicts lower levels of adolescents’ academic burnout. Moreover, parent–child relationship can indirectly affect academic burnout not only through the single mediating effect of interpersonal relationship on campus and academic self-efficacy but also through the chain mediating effect of interpersonal relationship on campus and academic self-efficacy. These findings help to understand the mechanism of parent–child relationship affecting academic burnout more comprehensively, and provide a theoretical basis for optimizing intervention programs for academic burnout.

Data availability

The data used and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Sun, J., Dunne, M. & Hou, X. Academic stress among adolescents in China. Australas. Epidemiol. 19, 9–12 (2012).

Yang, J. & Zhao, X. Parenting styles and children’s academic performance: Evidence from middle schools in China. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 113, 105017 (2020).

Lin, C. Psychology of Secondary School Students (China Light Industry Press, 2013).

Luo, H., Xu, Y., Xue, B. & Hu, Z. The concept analysis of teenagers’ weariness of study. Health Res. 41, 365–368 (2021).

Zhao, Y. Establishment and application of junior middle school students’ learning weariness scale. J. Shanghai Educ. Res. 10, 27–30 (2019).

Yavuz, G. & Dogan, N. Maslach burnout inventory-student survey (MBI-SS): A validity study. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 116, 2453–2457 (2014).

Zhang, Y., Gan, Y. & Cham, H. Perfectionism, academic burnout and engagement among Chinese college students: A structural equation modeling analysis. Pers. Individ. Differ. 43, 1529–1540 (2007).

Huang, J. et al. A survey on the degree and reasons of adolescents’ study-weariness. Theory Pract. Psychol. Couns. 5, 351–363 (2023).

Lin, S. & Huang, Y. Life stress and academic burnout. Act. Learn. High. Educ 15, 77–90 (2014).

Zheng, Y. Analysis of reasons and intervention measures of middle school students’ weariness of learning. J. Campus Life Ment. Health 11, 197–198 (2013).

Chen, G. et al. Annual Report on the Care of the Next Generation in China (Social Sciences Academic Press, Berlin, 2020).

Bilige, S. & Gan, Y. Hidden school dropout among adolescents in rural China: Individual, parental, peer, and school correlates. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 29, 213–225 (2020).

Bin-Bin, C., Yan, W., Ji, L. & Lian, T. And baby makes four: Biological and psychological changes and influential factors of firstborn’s adjustment to transition to siblinghood. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 24, 863–873 (2016).

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E. & Wall, S. N. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation Vol. 23 (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1978).

Yanhui, W. et al. Parent-child attachment and prosocial behavior among junior high school students: Moderated mediation effect. Acta Psychol. Sin. 49, 663–679 (2017).

Mulisa, F. Application of bioecological systems theory to higher education: Best evidence review. J. Pedag. Sociol. Psychol. 1, 104–115 (2019).

Wentzel, K. R. Social relationships and motivation in middle school: The role of parents, teachers, and peers. J. Educ. Psychol. 90, 202–202 (1998).

Wentzel, K. R. Are effective teachers like good parents? Teaching styles and student adjustment in early adolescence. Child Dev. 73, 287–301 (2002).

Lin, F. & Yang, K. The external and internal factors of academic burnout. Adv. Soc. Sci. Educ. Hum. Res. 615, 1815–1821 (2021).

Luo, Y., Zhao, M. & Wang, Z. Effect of perceived teacher’s autonomy support on junior middle school students’ academic burnout: The mediating role of basic psychological needs and autonomous motivation. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 30, 312–321 (2014).

Usmanovna, A. N. The role of partents in the upbringing of children. ACADEMICIA Int. Multidiscip. Res. J. 11, 1995–1999 (2021).

Li, J., Qian, K. & Liu, X. The impact and mechanisms of parent-child relationship quality and its changes on adolescent depression: A four-wave longitudinal study. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 17, e12606 (2024).

Tian, L., Liu, L. & Shan, N. Parent–child relationships and resilience among Chinese adolescents: The mediating role of self-esteem. Front. Psychol. 9, 1030 (2018).

He, H. The Research on the Relationship Among Parent–Child Conflict, Learning Burnout and Problem Behavior in Primary School Students (Hunan University of Science and Technology, 2017).

Shin, H., Lee, J., Kim, B. & Lee, S. M. Students’ perceptions of parental bonding styles and their academic burnout. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 13, 509–517 (2012).

Zhou, X., Liu, Y., Chen, X. & Wang, Y. The Impact of parental educational involvement on middle school students’ life satisfaction: The chain mediating effects of school relationships and academic self-efficacy. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 39, 691–701 (2023).

Ma, B., Dai, W. & Li, C. Migrant adolescents’ interpersonal relationship and subjective well-being: The mediating effect of academic burnout and academic engagement. Chin. J. Spec. Educ. 12, 63–71 (2019).

Tamm, A., Kasearu, K., Tulviste, T. & Trommsdorff, G. Links between adolescents’ relationships with peers, parents, and their values in three cultural contexts. J. Early Adolesc. 38, 451–474 (2018).

Schunk, D. & DiBenedetto, M. In pp. 268–282 (Routledge, 2022).

Deci, E. L. R. R. The support of autonomy and the control of behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 53, 1024–1037 (1987).

Demir Kaya, M. & Kaya, F. School burnout in adolescents: what are the roles of emotional autonomy and setting life goals?. Asia Pac. J. Couns. Psychother. 15, 4–15 (2024).

Odacı, H., Kaya, F. & Aydın, F. Does educational stress mediate the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and academic life satisfaction in teenagers during the COVID-19 pandemic?. Psychol. Sch. 60, 1514–1531 (2023).

Akomolafe, M. J., Ogunmakin, A. O. & Fasooto, G. M. The role of academic self-efficacy, academic motivation and academic self-concept in predicting secondary school students’ academic performance. J. Educ. Soc. Res. 3, 335–342 (2013).

Gao, X. Academic stress and academic burnout in adolescents: A moderated mediating model. Front. Psychol. 14, 1133706 (2023).

Yuan, S., Weiser, D. A. & Fischer, J. L. Self-efficacy, parent–child relationships, and academic performance: a comparison of European American and Asian American college students. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 19, 261–280 (2016).

Chen, P., Bao, C. & Gao, Q. Proactive personality and academic engagement: The mediating effects of teacher–student relationships and academic self-efficacy. Front. Psychol. 12, 652994–652994 (2021).

Liu, R. et al. Teacher support and math engagement: Roles of academic self-efficacy and positive emotions. Educ. Psychol. (Dorchester-on-Thames) 38, 3–16 (2018).

Marsh, H. W., Nagengast, B., Morin, A. J. S. & Parada, R. H. Construct validity of the multidimensional structure of bullying and victimization: An application of exploratory structural equation modeling. J. Educ. Psychol. 103, 701–732 (2011).

Zhang, W., Wang, M. & Fuligni, A. Expectations for autonomy, beliefs about parental authority, and parent-adolescent conflict and cohesion. Acta Psychol. Sin. 38, 868–876 (2006).

Van Damme, J. et al. A new study on educational effectiveness in secondary schools in Flanders: An introduction. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 13, 383–397 (2002).

Liang, Y. S. Study on Achievement Goals (Central China Normal University, 2000).

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. & Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903 (2003).

Hayes, A. F. & Scharkow, M. The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: does method really matter?. Psychol. Sci. 24, 1918–1927 (2013).

Alivernini, F. et al. Relationships between sociocultural factors (gender, immigrant and socioeconomic background), peer relatedness and positive affect in adolescents. J. Adolesc. (Lond. Engl.) 76, 99–108 (2019).

Kim, D. H. & Kim, J. H. Social relations and school life satisfaction in South Korea. Soc. Indic. Res. 112, 105–127 (2013).

Joyce, H. D. Does school connectedness mediate the relationship between teacher support and depressive symptoms?. Child. Sch. 41, 7–16 (2019).

Welty, C. W. et al. School connectedness and suicide among high school youth: A systematic review. J. Sch. Health 94, 469–480 (2024).

Liu, L. et al. Linking parent–child relationship to peer relationship based on the parent-peer relationship spillover theory: Evidence from China. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 116, 105200 (2020).

Gu, X. & Mao, E. Z. The impacts of academic stress on college students’ problematic smartphone use and Internet gaming disorder under the background of Neijuan: Hierarchical regressions with mediational analysis on escape and coping motives. Front. Psychiatry. 13, 1032700 (2023).

Tuerdi, H. A Study on the Influence of Stroke and School Belongingness on Junior High School Students’ Learning Weariness (East China Normal University, 2023).

Lei, A., You, H., Luo, B. & Ren, J. The associations between infertility-related stress, family adaptability and family cohesion in infertile couples. Sci. Rep. 11, 24220 (2021).

Ding, Z. et al. Latent profile analysis of family adaptation in breast cancer patients-cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 14, 21357 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants for completing the questionnaires.

Funding

This study was supported by Youth Project of the Fujian Provincial Social Science Foundation (No. FJ2022C102), Joint Funds for the Innovation of Science and Technology of Fujian Province (No. 2023Y9035), Special Health Fund of Fujian Provincial Department of Finance (BPB-2023LZY-2).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.S. and H.G. were responsible for study design, designing questionnaire, data collection and analysis, writing original draft. Z.Z. and Z.L. did study design, supervision, paper editing, supervision. W.J. and X.C. did investigation, data collection, data entry. F.W. did data entry. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University (Approval No.: MRCTA, ECFAH of FMU [2023]410) and was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All participants and their parents signed written informed consents prior to the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, J., Guo, H., Jiang, W. et al. A chain mediation model of parent child relationship and academic burnout of adolescents. Sci Rep 15, 7379 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92214-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92214-2