Abstract

The interface between self-compacting concrete (SCC) and rock has significant effects on the strength, damage, and crack growth of rock-filled concrete (RFC). In this paper, the strength, failure characteristics, and damage mechanism of SCC-rock composite specimens with different interface inclination angles under uniaxial compression are studied by physical tests and numerical simulations. The 3D finite element solver is developed by using CPU-GPU heterogeneous computing, which greatly improves computing efficiency and can be applied to large-scale mesh model calculation with tens of millions of degrees of freedom. The GPU-accelerated solver and the Realistic Failure Process Analysis (RFPA) theory are utilized to simulate the uniaxial compression of 3D mesoscopic stochastic mechanical models of three-phase SCC-rock composite specimens at different interface inclination angles. The results show that the compressive strength, peak strain, and accumulated acoustic emission (AE) energy of the composites decrease first and then increase with the increase of interface inclination angle, and the composites with different interface inclination angles show different failure characteristics. The progressive failure process of the composite specimen and its mechanical behavior are reproduced by numerical simulation. The research results provide an important reference for RFC engineering design and research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rock-filled concrete (RFC) technology is a method for constructing large-volume concrete dams1. A complete RFC structure is formed by pouring self-compacting concrete (SCC) into large rocks that have been piled up2,3. In RFC engineering construction, the SCC-rock composite model is a common structure, such as arch dam foundation4,5, wear-resistant layer6, and interlayer construction7,8. In addition, SCC and large rocks are easy to form different interface inclination angles. Affected by external load, construction technology, and interlayer processing, it often leads to various interface quality problems, such as poor bonding performance between SCC and rock, weak interlayer, and water seepage between layers. The interface inclination angle plays an important role in the mechanical behavior of SCC-rock composite9. Therefore, it is essential to study the mechanical properties and failure mechanism of SCC-rock composite with different interface inclination angles to evaluate the safety and stability of the RFC structure.

Currently, researchers have conducted extensive studies on the mechanical properties of concrete-rock composite specimens through physical experiments and numerical simulations10,11,12,13,14. Mouzannar et al.10 performed shear tests on concrete-rock specimens and found that the bond strength between concrete and rock, as well as the surface morphology of the rock and normal load, significantly influence the peak shear strength of the interface. Selcuk et al.11 studied the influence of interface inclination Angle on the strength and failure mechanism of rock-concrete specimens under different loading conditions. Yao et al.12 analyzed crack propagation processes at concrete-rock interface under varying strain rates using a fictitious crack model and criteria based on initial fracture toughness for crack extension. Guo et al.13 conducted uniaxial and triaxial compression tests on composite materials to establish a mechanical equivalent model for rock-concrete composites that considers interface roughness, deriving failure criteria for shear strength in this context. Guo et al.14employed acoustic emission (AE) and digital image correlation techniques to study fracture behavior in defect-containing rock-concrete composite specimens and explored how defect geometrical distribution impacts energy evolution. Although some scholars15argue that the bond strength of the interface has minimal impact on mechanical behavior during compression, it has a significant influence on the strength behavior of the interface in tension. However, the shear stress existing at the interface can easily lead to shear failure along the interface. In addition, unique casting processes combined with high fluidity of SCC may result in differences in mechanical performance and microstructure between SCC interfaces compared to ordinary concrete16. By using backscatter electron and nanoindentation techniques, Xie et al.9 discovered that RFC interfaces exhibit lower porosity and higher density than conventional counterparts. Tang et al.17 conducted direct tensile tests on SCC-rock specimens which revealed that the peak tensile strength of the interfaces is approximately 46% of SCC, and stress-strain curves display distinct brittle characteristics. Chen et al.18 performed direct shear tests and AE testing on SCC-rock specimens. They found an increase in both peak shear strength and stiffness with rising interface roughness and an increase in sheer crack quantity during failure stages. However, the current experimental studies primarily focus on the micro-characteristics of the interface between SCC and rock and the influence of interface roughness on the fracture mechanism, but few studies have focused on the influence of interface inclination angle on the strength and failure mechanism of composite specimens.

Due to the influence of factors such as specimen preparation, test process, and condition, experimental research to explore the failure mechanism of materials is complicated and expensive, and often difficult to replicate. These limitations greatly limit the applicability of physical tests. It is of great significance to study the failure mechanism of concrete and rock by numerical simulation19. Wang et al.20 used discrete element method to study the progressive failure process of concrete-rock bi-material discs under dynamic tensile load. Chen et al.21 combined a cohesive material model to study the crack tensile behavior of concrete-rock and put forward a mechanical model of the interfacial tensile behavior of concrete-rock. Dong et al.22used digital image processing technology and the Realistic Failure Process Analysis (RFPA) to reconstruct two-dimensional concrete-granite composite specimens and studied the mechanical properties and failure characteristics of specimens under compressive load. However, the concrete crack propagation should be 3D to accurately reflect the properties of the mortar matrix and aggregate. The establishment of 3D numerical models considering concrete mesoscopic structures usually includes millions of elements and involves tens of millions of degrees of Freedom (DOF), which poses a great challenge to the computational performance of central processing unit (CPU). The emergence of graphics processing unit (GPU) makes it possible for personal computers to achieve high-performance computing and plays an important role in various numerical computing methods23,24,25. Therefore, it is necessary to use GPU to improve the solving efficiency of 3D finite element method (FEM) and apply it to the 3D numerical model considering the meso-structure of materials.

To address the aforementioned issues, a 3D FEM solver was developed by utilizing CPU-GPU heterogeneous computing. Then, a numerical model of three-phase SCC-rock composite specimens is established and the feasibility and rationality of the numerical model are validated through physical experiments. This study systematically investigated the influences of interface inclination angle on the compressive strength, energy dissipation, and failure mechanism of SCC-rock composite specimens.

Numerical methods and GPU-accelerated computation

Probability distribution characteristics of quasi-brittle material properties

Rock and concrete are heterogeneous quasi-brittle materials, and their macroscopic cracking in the compression process is caused by the initiation, development, and expansion of a large number of micro-cracks and trans-scale nonlinear propagation26. The failure mechanism of the macroscopic mechanical behavior of materials can be explained from the mesoscopic scale. Based on the concept of representative volume element (RVE) at a mesoscopic scale27,28, Li and Tang29simulated the trans-scale progressive failure process of rock. As the smallest element for mesoscopic damage analysis, RVE represents the minimum volume that reflects statistical averages of material properties. Weibull probability function with a threshold can be used to describe the spatial distribution of certain mechanical properties of RVE30. Its basic equation is:

Where: J represents the mechanical properties of the mesoscopic element (such as elastic modulus or strength). J0 is the scale parameter related to the mean value of mechanical properties. m is the homogeneity index that determines the shape of the distribution function, which mainly controls the distribution of the material properties and reflects the homogenization of the material. The larger the value of m, the smaller the dispersion of the mechanical properties of the element (Fig. 1). The Weibull distribution function reflects the random distribution characteristics of the mechanical properties of material mesoscopic structures. Due to the randomness of non-uniformity, the macroscopic mechanical behavior of concrete will vary within a certain range. Even with the same parameters, the results of each numerical simulation, such as strength, number, and location of macroscopic cracks, are different. This helps to explain the characteristics of the strength randomness and failure mode diversity of concrete specimens in experiments and is of great significance for understanding the macroscopic brittle fracture behavior of concrete. Obviously, the division of model elements needs to meet a certain scale to accurately reflect the material heterogeneity. Especially in 3D FEM analysis of large-scale numerical models, breaking through the limitation of the computational efficiency has become a research hotspot31,32.

Energy dissipation and mesoscopic element constitutive relation

In the process of failure, rock and concrete usually release energy in various forms such as sound, force, light, and heat, and this process is irreversible. The energy dissipation will lead to material damage, while structural damage is caused by the release of elastic energy stored in the material33,34,35. Xie et al.36 proposed the strain energy of an element under 3D stress state:

Where, \(\bar {E}\)is the current elastic modulus of the element. \(\bar {\nu }\)is the Poisson ratio of the element. \({\sigma _i}(i=1,2,3)\)are the first, second, and third principal stresses of the element, respectively. For anisotropic elements, the formula is extended to:

Where, \({E_1}\) is the elastic modulus of the anisotropic element along the direction of principal stress. When the state of the element changes at step k, the element produces a stress drop, and the energy dissipation at the current step is:

Where, \({U_k}\) and \({U_{k - 1}}\) are the element strain energy at step k and step k−1, respectively. In the numerical simulation, the strain energy of the element is released in the form of AE. It not only reflects the local damage degree of the element but also reveals the law of energy transfer and distribution in the whole material system. Detailed information about the damage evolution of concrete and rock can be obtained by analyzing AE37.

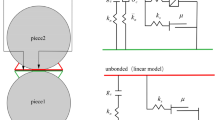

Tang30proposed the RFPA method based on damage mechanics and statistical mechanics models. The quasi-brittle materials such as rock and concrete are regarded as heterogeneous materials, whose mesoscopic elements obey the elastic-brittle relationship and mechanical properties obey the Weibull distribution. In this way, the macro nonlinear progressive failure process of quasi-brittle materials can be characterized38. Liang et al.39 extended the method to the study of 3D rock failure process. Li et al.40 applied it to the analysis and study of rock fluid-structure coupling problems. Yang et al.41improved the element damage path based on Tang30and extended it to multi-path damage analysis. At present, the RFPA method has been widely used to study the mechanical behavior and damage characteristics of quasi-brittle materials34,42,43,44. In the RFPA theory, the damage-energy dissipation constitutive relation of an element in a one-dimensional state is shown in Fig. 2, and the maximum tensile stress criterion and Mohr-Coulomb criterion are adopted as the criterion for determining element damage38. The element can be divided into the following five states: tensile separation, tensile damage, elasticity, compression damage, and compression contact45. In the process of changing from the elastic stage to the tensile or compression damage stage, the element will release high energy levels. In addition, low energy levels are released during the phase of compression damage and tension damage. This kind of energy release behavior is closely related to the initiation and propagation of microcracks in the material, which can provide an important theoretical basis for studying the mechanism of the interface on the mechanical properties of quasi-brittle materials.

GPU-accelerated 3D FEM solver

The macroscopic mechanical behavior of rock and concrete is significantly affected by the meso-structure. The numerical results of Li et al.29 show that when a small mesh size is adopted, the crack trajectory of the specimen during failure is smoother and closer to reality. Considering the distribution and composition of the meso-structure, it is necessary to construct a large-scale mesh model, which usually involves tens of millions of DOF. To overcome the challenge of high-performance computing requirements, many researchers have explored various parallelization techniques. Li et al.32 developed a CPU parallel FEM solver for simulating the trans-scale failure process of rock. Feng et al.42 established a cloud computing analysis system and simulated the fine failure process of real concrete. In practice, CPU has fewer cores and is better at complex logic and decision-making tasks. In addition to the CPU-based parallelization scheme, the GPU-accelerated computation scheme is gradually applied in FEM analysis.

The FEM programs considering element damage mainly include the model building module, FEM calculation module, damage analysis module, and post-processing results output module (Fig. 3). Among them, the FEM calculation module is the most time-consuming part. sparse matrix-vectormultiplication (SpMV) is an important operation in the FEM solution, which significantly affects the computational efficiency of iterative methods. The self-developed FEM solver based on CPU-GPU heterogeneous computing can take full advantage of these two components. The CPU is responsible for processing logically complex serial programs, and the GPU focuses on parallel computing programs. In GPU, each thread is assigned a unique thread ID and executes kernel functions, and writing and calling kernel functions for parallel computation is key in the program. To take full advantage of GPU performance, the vector kernel function46 is used to perform SpMV operations. Unlike the traditional scalar kernel function, which assigns a thread to each row of the matrix, the vector kernel function performs parallel reduction on each thread group and sums up the results of each thread. This method accesses indexes and data sequentially, which makes memory access in thread groups continuous. It overcomes the limitation of discontinuous access in the scalar kernel method and significantly improves the efficiency of SpMV computation.

To test GPU-accelerated computing performance, a series of numerical models of cube rock with the same side length (150 mm) but different numbers of elements are constructed. The failure process of these models under uniaxial compression is simulated by a personal computer. The homogeneity coefficient m of rock is 3, the expected value of element compressive strength is 50 MPa, and the expected value of elastic modulus is 20 GPa. The models of each mesh size were modeled using the same element mechanics parameters and simulated 5 times, and the average single step time was calculated. The computer configuration included an AMD Ryzen 9 7950X CPU, an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU, and 128 GB of RAM. For numerical models with different DOF, the single-step computing time of different calculation strategies is significantly different (Fig. 4). The single-step computation time in the FEM solution can be significantly reduced by using GPU acceleration. Even as the model is increased to 15 million DOF, the single-step computation time with GPU acceleration is kept under 15 s. The acceleration ratio is the ratio of the corresponding time for the same task to run in serial processing and parallel processing. It is an important indicator to measure the acceleration performance, and the higher the acceleration ratio, the better the acceleration effect. Under the condition of DOF < 1 million, there is little difference in the acceleration ratio between GPU acceleration and CPU parallelization processing. This is mainly because the GPU can efficiently solve, the transfer of data from the CPU to the GPU takes a lot of time, which reduces the efficiency of the GPU. When DOF > 1 million, the advantage of GPU acceleration is obvious, and the maximum acceleration ratio can reach 38.9. Even if the DOF reaches 15 million, the GPU acceleration ratio is still above 30. This shows that GPU has great advantages in processing large-scale mesh models and provides strong support for efficient solution of complex models.

The numerical model of SCC-rock composite

Physical test

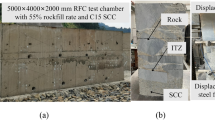

The SCC raw materials used were as follows: P. O42.5 ordinary Portland cement, fly ash, the natural medium sand with a fineness modulus of 2.5–3.1, gravel aggregates of 5–10 mm in size, local tap water, and polycarboxylate superplasticizer admixture with a water reduction rate of 27%. The mixed proportion of SCC is shown in Table 1. A slump expansion test was carried out to test the self-compaction of SCC. The results showed that the slump expansion of SCC was in the range of 680 ~ 710 mm, which met the filing requirements. The compressive strength of the SCC standard cube specimen was 16.05 MPa. To avoid the influence of different properties of rock material, high strength non-shrinkage grouting material was used as the rock aggregate of RFC, and its specific gravity is 2460 kg/m3. The compressive strength of the grouting material standard cubic specimen was 50.37 MPa, which met the rock strength requirements of actual RFC engineering.

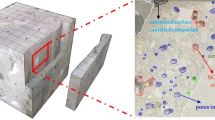

The interface between SCC and rock is a weak area with relatively low bonding strength and easy cracking. Compared with self-compacting mortar, the interface often exhibits lower strength, elastic modulus, and higher permeability. Figure 5 shows the scanning electron microscope (SEM) photos of the interface of self-compacting mortar and SCC-rock. It can be seen that the structure of self-compacting mortar is relatively dense. However, near the interface between SCC and rock, micro-cracks and unreacted fly ash particles can be clearly seen, and their micro-structure is relatively loose.

This paper prepared three types of specimens: rock, SCC, and SCC-rock composite specimens, each of which was a cube with a side length of 150 mm. The casting procedure for the SCC-rock composite specimens was as follows: first, the evenly mixed grouting material was poured into the cubic mold to a height of 75 mm and cured under standard conditions for 28 d. After curing, the stirred SCC was poured into the mold to flush with the mold mouth. The specimens were demolded 48 h after completion of pouring, and subsequent tests were performed after curing for 28 days under standard conditions (Fig. 6a, b). Uniaxial compression tests were carried out using the rock and concrete mechanics test system RMT-301 (Fig. 6c). In uniaxial compression testing, the ends of the cube specimen were in direct contact with the steel loading platens. The vertical displacement gauge on the vertical hydraulic cylinder of RMT-301 was used to measure vertical displacement and plot the stress-strain curve of the specimen under uniaxial compression. The test process was controlled by displacement, and the loading rate was set at 0.01 mm/s.

Numerical simulation of SCC

At the meso-structural level, SCC is mainly composed of coarse aggregate, self-compacting mortar, and the interface transition zone (ITZ) between the two. In this paper, a SCC model containing spherical coarse aggregate is constructed by C# language. The construction process is as follows (Fig. 7):

(1) Determine the size of the SCC specimen, the particle size range, and the content of coarse aggregate.

(2) Spherical coarse aggregates of different diameters are randomly generated in the space, and the interference judgment of spherical aggregates is carried out to ensure that the coarse aggregates are non-intrusive and within the specified range.

(3) According to the diameter of the spherical coarse aggregate generated into the model in turn. Establish a background mesh of n × n × n within the delivery area, and then use background grid method to establish an SCC mesh model containing coarse aggregates and self-compacting mortar.

(4) To generate the ITZ that wraps around coarse aggregate, the outermost layer of coarse aggregate is extended outward by one element as the ITZ element. Therefore, a three phase SCC mesh model containing self-compacting mortar, coarse aggregate, and ITZ can be established.

(5) Import the SCC mesh model into the developed FEM solver. The Weibull distribution function is used to set different mechanical performance parameters to self-compacting mortar, coarse aggregate and ITZ elements.

According to the choice of raw materials, the spherical coarse aggregate size of SCC is set to 5–10 mm and randomly generated in the cube according to continuous gradation. In addition, large-scale mesh models need to be generated to reflect the coarse aggregate content and shape inside the SCC.

Element mesoscopic mechanical parameter calibration

The SCC-rock composite should have the same geometric and mechanical properties as the physical specimen. The macroscopic mechanical parameters of 150 mm standard cube rock and SCC specimens were determined by a uniaxial compression test. It is worth noting that the parameters entered in the program correspond to the mechanical parameters of the mesoscopic element, not the macroscopic mechanical parameters of the numerical specimen. Therefore, it is necessary to calibrate the mechanical parameters of the element to make the macroscopic mechanical parameters of the numerical specimen consistent with the physical specimen, to ensure the accuracy and effectiveness of the numerical model.

In the RFPA theory, the micromechanical parameters of each component of rocks and SCC specimens can be determined through the macroscopic and mesoscopic transformation Eqs47,48 of materials:

Where \({f_{cs}}\) and \({E_{cs}}\) represent the macroscopic compressive strength and elastic modulus of the specimen, respectively. \({f_{cso}}\) and \({E_{cso}}\) are the compressive strength and elastic modulus of the mesoscopic element, respectively. For the same material, after setting the heterogeneity index m, the mesoscopic element mechanical parameters can be roughly calculated based on the results of physical experiments. Due to factors such as the size effect of the specimens, the ratio of compressive to tensile strength, and the residual strength coefficient of the element, multiple calibrations are still needed to obtain the most realistic microscopic mechanical parameters of the element. In concrete, the strength and elastic modulus of aggregate are high, and the material is relatively homogeneity22. Therefore, the homogeneity index of rock and coarse aggregate is set to 3 and 4, respectively. Due to the inclusion of fine aggregate in the matrix, the homogeneity of self-compacting mortar is lower43. Therefore, the homogeneity index of self-compacting mortar is set to 1.5. ITZ typically has higher porosity, lower strength, and elastic modulus than mortar. As the weakest area in concrete, ITZ significantly affects the propagation of cracks and has a significant impact on the mechanical behavior of concrete. Therefore, the homogeneity coefficient of ITZ is set to 1.4, and both the elastic modulus and compressive strength are lower than those of mortar. After determining the homogeneity index m, the parameters are repeatedly calibrated and adjusted by comparing with the results of physical experiments. Finally, the mechanical parameters of the element of each material in the composite specimens are obtained (Table 2). Among them, the compressive strength and elastic modulus of the elements follow the Weibull distribution and use the same heterogeneity index.

Uniaxial compression simulations were carried out on rock and SCC specimens according to the parameters in Table 2, and compared with the physical test results (Fig. 8). The numerically simulated crack propagation patterns of rock and SCC specimens are consistent with the physical tests (Fig. 8a, b). In numerical simulation, the bottom of the specimen is fixed, a vertical load of 0.002 mm/step is applied to the top, and lateral displacement is allowed to occur to simulate actual uniaxial compression loading conditions. The black areas represent element damage due to tensile separation. The final failure mode of rock specimen is mainly tensile failure. With the increase of strain, the stress of the specimen decreases rapidly to the residual strength after reaching the peak strength, showing typical brittle failure characteristics. Because of the influence of the internal structure and loading conditions49 of the specimen, the surface of SCC is mainly composed of longitudinal cracks, accompanied by a small amount of shear cracks. As a weak area in SCC, the internal damage of SCC is mainly the ITZ around the coarse aggregate. Cracks initiate, form, and propagate in the ITZ region, ultimately leading to macroscopic damage of SCC. Significant nonlinear characteristics can be observed in SCC specimens near the peak stress, which are almost absent in rock specimen (Fig. 8c). In addition, influenced by the closure of internal microcracks and the influence of measuring instruments, there is a significant initial nonlinear stage in the stress-strain curves of rocks and SCC specimens in physical experiments. Due to the lack of a microcrack closure stage in rock and SCC specimens in numerical simulations, the peak strain obtained from numerical simulations is lower than that obtained from physical experiments.

Figure 9 shows the average compressive strength and elastic modulus obtained from numerical simulations and physical tests of rock and SCC standard cubic specimens, together with the corresponding coefficient of variation for each test type. Among them, 5 specimens were tested for each material to ensure data reliability. The failure mode, peak strength, and elastic modulus of the physical test and numerical simulation are very close. These results show that the mesoscopic parameters in Table 2 are reasonable and the subsequent numerical simulation results are reliable.

Numerical model establishment and verification

In this study, the interface inclination angles of 0°, 15°, 30°, 45°, 60°, 75°, and 90° were considered (Fig. 10a). The model consists of two parts, left and right or upper and lower, representing SCC and rock respectively. ITZ with the same material parameters is set between mortar and coarse aggregate, mortar and rock. The composite consists of four materials: rock, self-compacting mortar, coarse aggregate, and ITZ. In fact, the casting direction50 of concrete also has a significant impact on the compressive strength of the composite. This paper simplifies the model elements, assuming them as isotropic elements and considering the heterogeneity of the material.

The specimen was fixed at the bottom and a vertical load of 0.002 mm/ step was applied to the top to simulate uniaxial compression loading conditions (Fig. 10b). The model is a cube with a side length of 150 mm, and the elements are divided into x ×y ×z = 150 × 150 × 150, with a total of 3.375 million elements. In the program, information such as AE event, AE energy, and AE location can be simulated and recorded, and the number of damaged elements and energy released can be calculated.

Figure 11 shows the comparison of the results of physical tests and numerical simulations for the composite specimens with interface inclination θ = 0° and 90°. When θ = 0°, the SCC and the rock jointly bear the load. Even if SCC failure occurs, the rock with higher strength can continue to bear part of the load. After reaching the first stress peak, the stress still increases slowly with the increase of strain, indicating that the specimen still has a certain bearing capacity. When the second stress peak is reached, the rock macroscopic failure occurs, and the composite specimen completely loses its bearing capacity. The final failure pattern shows that the ITZ is easily affected by horizontal tensile stress, resulting in longitudinal cracks. When θ = 90°, macroscopic cracks mainly appear in the SCC region with low strength. With the increase of load, the cracks gradually extend to the rock, showing a “Y-shaped” failure mode. Because the failure of SCC is considered as composite specimen failure, the peak strength of θ = 90° specimen is lower than that of θ = 0° specimen. The stress-strain curves of physical test and simulation are consistent, so the numerical model established in this paper is reliable.

Results and analysis

Strength characteristic

To analyze the strength characteristic of SCC-rock composite specimens, the relationship curves of compressive strength, peak strain to the interface inclination angle θ are obtained by uniaxial compression numerical simulation (Fig. 12). The compressive strength and peak strain of the composite decreased first and then increased with the increase of θ. This indicates that compressive strength and peak strain are highly sensitive to interface inclination angle. In the range of 0° to 45°, the composites are significantly affected by the interface effect. The peak strength of the composite with θ = 0° is the highest, and its value is 20.93 MPa. Compared with the complete SCC specimen, the strength was increased by 30.6%. The peak strength of the θ = 45° composite is the lowest and slightly lower than that of the SCC specimen. When θ > 60°, the influence of interface inclination angle on compressive strength decreases. Although the peak strength is increased compared to θ = 45°, the change is not large.

Failure process evolution

Figure 13 shows the stress-strain curve, AE energy variation, and the evolution of the maximum principal stress field of the composites under uniaxial compression tests with interface inclination angle θ = 0° and 15°. When θ = 0° (Fig. 13a), the SCC and rock bear the load together and distribute the load evenly, so that the specimen has a high bearing capacity and produces two stress peaks. At the initial loading stage (point I), a remarkable stress concentration occurs at ITZ in SCC. Due to the relatively low strength of ITZ, the longitudinal tensile cracks are first initiated and propagated in the ITZ region. When the first stress peak (point II) is reached through the process of energy accumulation, the SCC gradually loses its bearing capacity due to failure, and the external load is borne by the rocks with higher strength. During the two stress peaks, the macroscopic cracks inside the SCC region expand and extend, accompanied by the continuous release of low energy levels. At the second stress peak (point III), the rock bears most of the load and begins to shear failure, and obvious longitudinal tensile cracks have formed in the SCC region. After that, the stress of the composite rapidly drops to the residual strength (point IV), and the rock releases high energy levels and form macroscopic shear cracks. The final results show that the failure of the composite specimen is caused by the joint failure of SCC, rock, and ITZ.

When θ = 15° (Fig. 13b), the composite specimen still produces two stress peaks, but the first stress peak is the peak strength of the composite. Although SCC and rock share the load, the change of θ causes the proportion of SCC to rock at the top of the composite to change. When the first stress peak is reached (point II), there is an obvious stress concentration near the interface at the top of the specimen. At the same time, it can be observed that a small number of macroscopic cracks are generated in the SCC region near the interface at the top of the specimen due to stress concentration. This indicates that with the increase of θ, the proportion of rock at the top decreases, resulting in stress concentration at the top of the composite. As a result, the macroscopic crack formation is earlier and the compressive strength of the composite is reduced. Eventually, both the θ = 15° and θ = 0° composite fail due to macroscopic fractures in the SCC, interface, and rock region.

As the interface inclination angle increases (θ = 30°, 45°), the compressive strength and peak strain of the composite specimens gradually decrease (Fig. 14). When θ = 30° (Fig. 14a), the accumulated AE energy decreased and changed from a single peak to multiple peaks, mainly concentrated in the post-peak stage. Additionally, the macroscopic cracks in the SCC region change from longitudinal tensile cracks to inclined shear cracks along the interface. When θ = 45° (Fig. 14b), macroscopic shear cracks are more likely to appear in the SCC region, and only a few cracks extend to the rock region. This indicates that damage is more likely to occur in the SCC region with the increase of the interface inclination angle, and the phenomenon of stress concentration at the top is more likely to cause macroscopic cracks along the interface. Finally, the macroscopic cracks almost permeate the whole interface, and the compressive strength of the composite specimen decreases.

The compressive strength of the composite specimens with interface inclination angle θ = 60° and 75° is increased compared with θ = 45° (Fig. 15a, b), and the final failure pattern also changes. The damage and failure mainly occur in the SCC region, and almost no macroscopic cracks are formed in the rock region, and the specimens show more AE precursors before reaching the stress peak. This indicates that when θ is greater than 45°, the influence of the θ decreases, and the damage of the composite mainly depends on the SCC with lower strength. Therefore, with the increase of θ, the compressive strength and accumulated AE energy of the composite had little difference.

The composite with θ = 90° eventually exhibits a “Y-shaped” failure pattern (Fig. 15c). Due to the stiffness difference between the SCC and the rock, the materials near the interface are bound to each other. The lower rock limits the lateral deformation of the upper SCC, and the lateral constraint stress enhances the strength of the SCC near the interface. In contrast, the rock near the interface is subjected to horizontal tensile stress which reduces its strength. In addition, since the rock strength is much higher than the SCC strength, even if the rock strength near the interface is reduced, it is still greater than the strength of the SCC. Therefore, under longitudinal loading, macroscopic cracks first germinate and form in the SCC region far from the interface, then extend to the SCC near the interface, and finally to the rock region near the interface.

Under uniaxial compression conditions, different crack propagation modes can be observed for the composite specimens with different interface inclination angles. The first is that cracks only appear in the SCC region, and the failure of composite is caused by SCC failure, while the integrity of the rock region is high. This occurs mainly at θ = 60° and 75°. The second is that the fractures first form in the SCC region with low strength, and then gradually extend and expand to the rock region, and finally the SCC and rock jointly fail. This occurs mainly at θ = 90°. The third mode mainly occurs at θ ≤ 45°, and the failure of the composite specimen is caused by the joint failure of SCC, rock, and the interface. These three failure modes reflect the significant influence of the interface inclination angle on the failure characteristics of the composite specimen, and the interface effect plays a key role in the failure process of the composite.

Damage mechanism

AE is a transient elastic wave caused by the rapid release of energy in the local part of the material, which reflects the characteristics of crack initiation, formation, and propagation during the loading process. AE characteristics are crucial to understanding the mechanism of material deformation and failure51. Figure 16 shows the AE events and AE energy of composite specimens with different interface inclination angles during uniaxial compression. The red and blue spheres represent AE due to tensile stress and compressive stress, respectively. The larger the radius of the sphere, the higher the energy released when the element is damaged. It can be found that a large number of red spheres appear in all specimens and are first generated in the SCC. This shows that in the mesoscopic view, the failure of the material is mainly tensile failure and SCC is damaged first. The AE behavior of composites can be divided into four typical stages. (a) a small amount of AE energy release stage. At this stage, most of the energy absorbed by the material is stored in the form of elastic strain energy, and a small amount is released in the form of AE due to the initiation of cracks. Therefore, the AE events increase linearly with the increase of strain, but only a small amount of AE energy is released. (b) AE energy release jump stage. As the deformation of the specimen increases, the AE energy increases and jumps rapidly, and the initial cracks gradually develop and extend. (c) AE energy sudden jump phase. At this stage, AE energy jumps rapidly to maximum due to the unstable expansion of cracks. For composite specimens with different interface inclination angles, the number of AE energy peaks is also different, and the AE energy peaks often occur at the moment of stress drop, indicating the formation of macroscopic cracks and the failure of specimens. (d) Post-peak AE energy stage. The bearing capacity of the specimen has been lost, and only a few AE events and AE energy are generated.

The AE event peak value of the composite with interface θ = 0° is 3097, and its AE distribution range and AE energy are significantly larger than other specimens. It can be seen that the total energy dissipation of θ = 0° is the largest, and the internal damage is also the most serious. The distribution number of spheres with θ = 45° is significantly lower than that of the composite specimens with other interface inclination angles, and the spheres are generated along the interface between SCC and rock, indicating the internal damage degree is minimal. When θ > 45°, the AE events and AE energy variation processes have little difference, and AE is almost distributed in the SCC region. At this time, the higher interface inclination angle has a weak influence on the damage of the composite, and the damage development is determined by the lower strength SCC. This means that the variation of the interface inclination angle changes the damage distribution inside the composite. The different failure modes correspond to different energy dissipation situations, and energy dissipation analysis can better describe the deformation and failure process of materials, which is consistent with the research conclusion of Xie et al.36.

As θ increases, the accumulated AE energy of the composites firstly decreases and then increases (Fig. 17a), showing the same variation trend as the compressive strength. The correlation between the AE energy and the compressive strength can be obtained through the linear fitting function (Fig. 17b). The correlation coefficient R2 between the compressive strength and accumulated AE energy is 0.90, indicating a strong linear relationship between the two. This shows that the energy dissipation is closely related to the strength characteristics of the composite specimens under uniaxial compression. Energy dissipation will cause internal damage and change the failure mode. When the accumulation of energy dissipation reaches the threshold, the composite will eventually fail.

Conclude

In this study, a 3D FEM solver is developed based on CPU-GPU heterogeneous computing, and a numerical model of SCC-rock composite specimens containing coarse aggregate and ITZ is established. Through physical tests and numerical simulation, the uniaxial compression behavior and failure characteristics of the composite with different interface inclination angles are studied. The contributions and conclusions can be drawn as follows:

(1) The interface inclination angle has a significant influence on the uniaxial compressive strength and deformation of SCC-rock composite specimens. The compressive strength and peak strain decrease first and then increase with the interface inclination angle. The compressive strength with the interface inclination angle of 0° is the highest. When the interface inclination angle is 45°, the compressive strength is the lowest and slightly lower than that of the SCC specimen. When the interface inclination angle is greater than 45°, the compressive strength of the specimen increases gradually, but the difference is small.

(2) The crack propagation is significantly affected by the interface inclination angle. When the interface inclination angle is 0°−45°, the SCC, the interface and the rock region are all damaged. When the interface inclination angle is 60°−75°, only the SCC region is damaged. When the interface inclination angle is 90°, the cracks mainly occur in the SCC region and then extend to the rock region.

(3) The interface inclination angle changes the AE energy characteristics of the composite. With the increase of the interface inclination angle, the accumulated AE energy decreases first and then increases. The composite with the interface inclination angle of 0° has the highest accumulated AE energy and the highest internal damage degree. The accumulated AE energy is the smallest when the interface inclination angle is 45°, and it is mainly distributed along the interface. When the interface inclination angle is greater than 45°, the internal damage of the composite is mainly concentrated in the SCC region.

(4) The self-developed 3D FEM solver using GPU acceleration greatly improves the computational efficiency, which is suitable for large-scale mesh models. Uniaxial compression tests are carried out on rock with millions of DOF, and the maximum speedup is 38.9.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Jin, F., An, X., Shi, J. & Zhang, C. Study on rock-filled concrete dam. J. J. Hydraulic Eng. 36, 1347–1352. https://doi.org/10.3321/j.issn:0559-9350.2005.11.013 (2005).

Xie, Y., Corr, D. J., Chaouche, M., Jin, F. & Shah, S. P. Experimental study of filling capacity of self-compacting concrete and its influence on the properties of rock-filled concrete. J. Cem. Concrete Res. 56, 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2013.11.010 (2014).

Mostafa, M., Jin, F. & Xu, Y. Analyzing the filling performance parameters of self-compacted mortar in rock filled concrete. J. Constr. Building Mater. 433, 136581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.136581 (2024).

Jin, F., Zhang, G., Lou, S., He, H. & Zhang, Q. Analysis and research on arch-beam load sharing method of integrally pouring rock-filled concrete arch dam. J. J. Hydraulic Eng. 51 (10), 1307–1314. https://doi.org/10.13243/j.cnki.slxb.20200301 (2020).

Jin, F., Zhang, G. & Zhang, Q. Temperature analysis for Lyutang RFC arch dam in construction period. J. J. Hydraulic Eng. 51 (06), 749–775. https://doi.org/10.13243/j.cnki.slxb.20200237 (2020).

Luo, T., Li, J., Zhang, T. & Jin, F. Crack propagation behavior of self-compacting concrete interface based on DIC method. J. J. Water Resour. Water Eng. 35 (1), 143–153. https://doi.org/10.11705/j.issn.1672-643X.2024.01.17 (2024).

Zhou, H., An, X., Ren, M., Li, P. & Wang, C. Effect of rock shear keys on the shear performance of cold joints in rock-filled concrete structures: experimental and numerical investigation. J. Constr. Building Mater. 336, 127315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.127315 (2022).

Zhang, M., Tang, X., Li, Y., Liu, N. & Yang, T. Shear tests and meso-scale simulation of cold joint structures in rock-filled concrete: considering the mutual contact effects between component materials. J. Constr. Building Mater. 451, 138768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.138768 (2024).

Xie, Y., Corr, D. J., Jin, F., Zhou, H. & Shah, S. P. Experimental study of the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) of model rock-filled concrete (RFC). J. Cem. Concrete Compos. 55, 223–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2014.09.002 (2015).

Mouzannar, H., Bost, M., Leroux, M. & Virely, D. Experimental study of the shear strength of bonded concrete–rock interfaces: surface morphology and scale effect. J. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 50, 2601–2625. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-017-1259-2 (2017).

Selcuk, L. & Asma, D. Experimental investigation of the rock–concrete Bi materials influence of inclined interface on strength and failure behavior. J. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 123, 104119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2019.104119 (2019).

Yao, J., Geng, Y., Yuan, W. & Dong, W. Experimental and numerical investigations on rate-dependent fracture behavior of concrete-rock interface. J. Theoretical Appl. Fract. Mech. 133, 104646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tafmec.2024.104646 (2024).

Guo, Z., Gao, J. & You, J. Research on compression failure criteria and characteristics of rock-concrete assemblies with rough interfaces. J. Eng. Fract. Mech. 311, 110544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2024.110544 (2024).

Guo, T., Zhang, Q., Liu, K., Chang, X. & Zou, L. Co-effects of parallel flaws and interface characteristics on the fracture behavior of rock-concrete composite specimens. J. J. Building Eng. 97, 110920. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2024.110920 (2024).

Saiang, D., Malmgren, L. & Nordlund, E. Laboratory tests on shotcrete-rock joints in direct shear, tension and compression. J. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 38, 275–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-005-0055-6 (2005).

Jin, F., Huang, D., Lino, M. & Zhou, H. A. Review of Rock-Filled concrete dams and prospects for Next-Generation concrete dam construction technology. J. Eng. 32, 99–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2023.09.020 (2023).

Tang, X., Shi, J., Zhang, Z. & Zhang, C. Meso-scale simulation and experimental study on self-compacted rock-fill concrete. J. J. Hydraulic Eng. 40 (07), 844–849857. https://doi.org/10.3321/j.issn:0559-9350.2009.07.011 (2009).

Chen, Y. et al. Effects of roughness on shear properties and acoustic emission characteristics of bonded Rock-Concrete interfaces. J. Constr. Building Mater. 398, 132405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132405 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. A benchmark study of different numerical methods for predicting rock failure. J. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 166, 105381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2023.105381 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. Discrete element modeling of rock-concrete bi-material discs under dynamic tensile loading. J. Constr. Building Mater. 327, 126962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126962 (2022).

Chen, J., Zhu, Z., Zhou, L., Ma, L. & Wang, H. Failure mechanism analysis and tensile constitutive model of basalt fiber concrete-rock interface based on fiber surface modification. J. Compos. Struct. 338, 118110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2024.118110 (2024).

Dong, Z. et al. Mechanical properties and failure mechanism of concrete-granite composite specimens under compression load. J. Constr. Building Mater. 435, 136768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.136768 (2024).

Liu, G., Xu, W. & Govender, N. Wilke. D. N. Simulation of rock fracture process based on GPU-accelerated discrete element method. J. Powder Technol. 377, 640–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2020.09.009 (2021).

Yang, P., Zang, M., Zeng, H. & Guo, X. The interactions between an off-road tire and granular terrain: GPU-based DEM-FEM simulation and experimental validation. J. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 179, 105634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2020.105634 (2020).

Zhou, Q., Xu, W., Feng, Z. A. & Coupled FEM-MPM GPU-based algorithm and applications in geomechanics. J. Computers Geotechnics. 151, 104982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2022.104982 (2022).

Xu, X., Ma, S., Xia, M., Ke, F. & Bai, Y. Synchronous multi-scale observations on rock damage and rupture. J. Theoretical Appl. Fract. Mech. 44 (2), 146–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tafmec.2005.06.003 (2005).

Esmaieli, K., Hadjigeorgiou, J. & Grenon, M. Estimating geometrical and mechanical REV based on synthetic rock mass models at Brunswick mine. J. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 47 (6), 915–926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2010.05.010 (2010).

Zhang, W., Chen, J., Yuan, X., Xu, P. & Zhang, C. Analysis of RVE size based on three-dimensional fracture numerical network modelling and stochastic mathematics. J. Q. J. Eng. Geol. Hydrogeol. 46 (1), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1144/qjegh2011-045 (2013).

Li, G. & Tang, C. A. A statistical meso-damage mechanical method for modeling trans-scale progressive failure process of rock. J. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 74, 133–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2014.12.006 (2015).

Tang, C. A. Numerical simulation of progressive rock failure and associated seismicity. J. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 34 (2), 249–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0148-9062(96)00039-3 (1997).

Zehner, B., Hellwig, O., Linke, M., Gorz, I. & Buske, S. Rasterizing geological models for parallel finite difference simulation using seismic simulation as an example. J. Computers Geosci. 86, 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cageo.2015.10.008 (2016).

Li, G., Tang, C. A. & Liang, Z. Z. Development of a parallel FE simulator for modeling the whole trans-scale failure process of rock from meso-to engineering-scale. J. Computers Geosci. 98, 73–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cageo.2016.08.014 (2017).

Xie, H., Peng, R. & Ju, Y. Energy dissipation of rock deformation and fracture. J. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 23 (21), 3565–3570. https://doi.org/10.3321/j.issn:1000-6915.2004.21.001 (2004).

Zhang, K., He, R., Jiang, Z., Li, N. & Zhang, K. Fracture behavior of a brittle material with a hidden spherical hole: physical experiments and numerical simulations. J. Eng. Fract. Mech. 307, 110279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2024.110279 (2024).

Ma, B. et al. Experimental investigation into influence of surrounding rock on strainburst: insight from failure process and energy partition. J. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 175, 105685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2024.105685 (2024).

Xie, H., Li, L., Peng, R. & Ju, Y. Energy analysis and criteria for structural failure of rocks. J. J. Rock. Mech. Geotech. Eng. 1 (1), 11–20. https://doi.org/10.3724/sp.j.1235.2009.00011 (2009).

Carpinteri, A., Lacidogna, G., Corrado, M. & Di, E. Cracking and crackling in concrete-like materials: A dynamic energy balance. J. Eng. Fract. Mech. 155, 130–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2016.01.013 (2016).

Tang, C. A. & Tang, S. Applications of rock failure process analysis (RFPA) method. J. J. Rock. Mech. Geotech. Eng. 3 (4), 352–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-35525-8_17 (2011).

Liang, Z. Z., Tang, C. A., Li, H. X. & Zhang, Y. B. Numerical simulation of 3-d failure process in heterogeneous rocks. J. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 41, 323–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2003.12.139 (2004).

Li, G., Tang, C. A., Li, L. & Li, H. An unconditionally stable explicit and precise multiple timescale finite element modeling scheme for the fully coupled hydro-mechanical analysis of saturated poroelastic media. J. Computers Geotechnics. 71, 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2015.09.003 (2016).

Yang, T., Liu, H. Y. & Tang, C. A. Scale effect in macroscopic permeability of jointed rock mass using a coupled stress–damage–flow method. J. Eng. Geol. 228, 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2017.07.009 (2017).

Feng, X., Gong, B., Tang, C. & Zhao, T. Study on the non-linear deformation and failure characteristics of EPS concrete based on CT-scanned structure modelling and cloud computing. J. Eng. Fract. Mech. 261, 108214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2021.108214 (2022).

Yu, Q., Liu, H., Yang, T. & Liu, H. 3D numerical study on fracture process of concrete with different ITZ properties using X-ray computerized tomography. J. Int. J. Solids Struct. 147, 204–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2018.05.026 (2018).

Lang, Y., Liang, Z. & Dong, Z. Three-dimensional finite element simulation and reconstruction of jointed rock models using CT scanning and photogrammetry. J. J. Rock. Mech. Geotech. Eng. 16 (4), 1348–1361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2023.08.008 (2024).

Nishimatsu, Y., Okubo, S. & Fukui, K. Modified stress severity and safety factor. J. J. MMIJ. 110 (4), 343–346. https://doi.org/10.2473/shigentosozai.110.343 (1994).

Bell, N. & Garland, M. Efficient sparse matrix-vector multiplication on CUDA. Nvidia Technical Report NVR-2008-004, Nvidia Corporation. (2008).

Tang, C. & Zhu, W. Damage and Fracture of Concrete-Numerical Test (Science press at Peking, 2003).

Yu, L. et al. Study on compressive size effect of rock-filled concrete considering initial pores. J. Struct. 71, 108030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2024.108030 (2025).

Bandeira, M., Torre, K., Kosteski, L., Marangon, E. & Riera, J. Influence of contact friction in compression tests of concrete samples. J. Constr. Building Mater. 317, 125811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125811 (2022).

Kosteski, L., Marangon, E., Riera, J. D., Santos, F. & Bandeira, M. Assessment of concrete anisotropy in relation to the direction of casting. J. Revista Sul-Americana De Engenharia Estrutural. 15 (2). https://doi.org/10.5335/rsaee.v15i2.7852 (2018).

Li, A. et al. Influence of heterogeneity on mechanical and acoustic emission behaviours of stratified rock specimens. J. Eur. J. Environ. Civil Eng. 22 (sup1), s381–s414. https://doi.org/10.1080/19648189.2017.1373709 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [No.52069004]; Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Projects [QKHJC-ZK[2021]YB293]; Research Fund for Talent Introduction of Guizhou University [(2019) No.57].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: G.W and T.Y. Manuscript writing and preparation: G.W and Y.L. Data collection and analysis: G.W., T.R., and L.Y. Revised the manuscript text Q.C., M.S., and G, S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, G., Yu, L., Yang, T. et al. Research on damage characterization of SCC and rock composite specimens based on CPU and GPU heterogeneous code acceleration. Sci Rep 15, 7641 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92443-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92443-5