Abstract

The increase in the chemsex phenomenon among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) is alarming, as it is associated with risky sexual behaviors, including condomless sex and multiple sex partners. Despite increasing concerns, there is nonexistent research on chemsex among GBMSM in Nepal. Therefore, our study aimed to identify the prevalence and factors associated with engagement in chemsex among GBMSM in Nepal. A cross-sectional online survey of 842 Nepali GBMSM was conducted between March and May 2024. Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with chemsex engagement within the past 12 months. Among 842 participants (mean age 27.6 ± 7.1 years), 24.7% reported ever engaging in chemsex, and 19.1% did so in the past 12 months. GBMSM who had completed high school were less likely to have engaged in chemsex in the past 12 months (aOR: 0.5; 95% CI: 0.3–0.8). However, GBMSM who reported having multiple sex partners (aOR: 9.6; 95% CI: 1.3–71.4), being involved in party/group sex in the past 12 months (aOR: 2.5; 95% CI: 1.5–3.9), and with depressive symptoms (aOR: 2.0; 95% CI: 1.3–3.0) were more likely to have engaged in chemsex in the past 12 months. An integrated approach is urgently needed, encompassing awareness raising, safe drug use support, sexual health services, and mental health care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chemsex, also known as sexualized drug use, Chem Fun (CF), or party and play (PnP), is commonly regarded as sex or sexual activities carried out under the influence of chemical drugs1,2. It mostly encompasses the use of psychoactive substances, such as crystal methamphetamine, mephedrone, gamma-hydroxybutyrate, or gamma-butyrolactone (GHB/GBL) before and during sexual activities or sex3,4,5. These drugs are presumed to prolong sexual motivation, pleasure, and activity, to increase sexual self-confidence, as well as to enhance the perceived quality of sex in other ways6,7,8.

In recent years, an escalating magnitude of chemsex practice has been observed, especially among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM)4,6,9. A systematic review estimated that the prevalence of chemsex involving non-injecting drug use ranges from 3 to 29% among GBMSM, while chemsex with injecting drug use ranges from 1 to 50%, based on studies predominantly from the United States and Western Europe10. In the Asian context, a meta-analysis found a pooled prevalence of chemsex among GBMSM to be 19% (95% confidence interval [CI] 15%-23%)4. Peak divergence of the information that chemsex facilitates feelings of sexual arousal and triggers feelings of euphoria throughout and after sexual engagement might have reinforced the GBMSM community for chemsex practice2,6. Such emerging practice of chemsex is certain to pose an alarming public health threat to the GBMSM community globally4,11.

Existing research on chemsex indicates its association with high-risk sexual behavior and various biopsychosocial risks, such as cravings and withdrawal symptoms, overdose, dehydration, and heart failure1,2,4,10,12,13,14,15. Likewise, it is seen as linked with various sexually transmitted infections/diseases, including HIV, as well as engagement in multiple partners sex, group sex, and party sex1,9,10,13. While it is not possible to depict the causation, studies have notably pointed out that men engaged in chemsex with men are more likely to report engaging in HIV transmission risk behaviors than men who do not16. On the other hand, chemsex is consistently linked with an increased likelihood of experiencing depressive symptoms17. Interestingly, in a recent study, chemsex has been identified as a coping mechanism for the stressors such as homophobia, stigma, discrimination, rejection, and isolation that MSM encounter18.

Unfortunately, the majority of research on chemsex stems largely from the global North4,5,8,9,10. There is a notable absence of empirical evidence concerning the prevalence and underlying drivers of chemsex in culturally sensitive countries like Nepal, where the GBMSM population continues to face marginalization, stigma, and limited access to healthcare19,20,21. Despite some incremental advancements, discussions around sexual behaviors remain largely taboo, contributing to chemsex being a severely underexplored issue among GBMSM. This underscores a significant research gap in the field, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) like Nepal. This study aimed to bridge the research gap by assessing the prevalence of chemsex and associated factors among GBMSM in Nepal.

Results

Participant’s characteristics

Table 1 describes participant characteristics. The mean (± SD) age of the participants was 27.6 (± 7.1) years. The majority of the participants were 25 and above (63.3%). Most of the participants identified as Janajati (41.5%), Brahmin/Chhetri (29.8%), and Madhesi (18.2%) ethnicities. Over half of the participants were single (63.2%), and less than high school/PCL graduates (54.1%). Among the study participants, 22.3% experienced depressive symptoms, and nearly one-third did not seek mental health care even when they needed it (34.9%). Most of the participants reported that they tested for HIV at some point in their lifetime (81.7%), with 12.3% of those testing HIV positive.

In terms of sexual behaviors, over two-thirds of the participants reported having anal sex in the last 12 months (72.6%), and of those, more than half (356/611; 58.3%) reported to have engaged in condomless sex and had multiple sex partners (556/611; 91.0%). Furthermore, nearly one-third of the participants (29.5%) reported to have engaged in transactional sex in the last 12 months.

Chemsex practices and associated factors

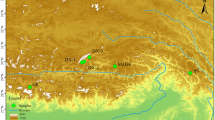

Overall, 24.7% of participants reported ever engaging in chemsex, with 19.1% involved in the past 12 months as shown in Table 1. Recent chemsex involvement was highest in Sudhurpaschim (29.4%), followed by Koshi (26.9%) and Madhesh (25.0%) provinces as shown in Fig. 1.

GBMSM who were high school graduates were less likely to have engaged in chemsex in the past 12 months (aOR: 0.5; 95% CI: 0.3–0.8). However, GBMSM who reported having multiple sex partners (aOR: 9.6; 95% CI: 1.3–71.4), being involved in party/group sex in the past 12 months (aOR: 2.5; 95% CI: 1.5–3.9), and with depressive symptoms (aOR: 2.0; 95% CI: 1.3–3.0) were more likely to have engaged in chemsex in the past 12 months as shown in Table 2.

Discussion

There is currently no research on chemsex practices documented in Nepal, where drug use and same-sex behavior are highly stigmatized and discriminated against. This first-of-its-kind study provides important insights into chemsex practices and has implications for future interventions among marginalized communities. The prevalence of chemsex practices among GBMSM in Nepal was found to be similar to that in high-income countries like Portugal22, Netherlands8, and Norway23 or higher than in some Asian countries such as Malaysia24, China25, and Hongkong26. This variation might be due to the recent emergence of the chemsex phenomenon in Nepal, in contrast to its longer recognition in other regions. Importantly, recent law enforcement reports indicate that synthetic drugs are being trafficked across the land border from neighboring countries, underscoring the risk of rising chemsex practices in Nepal27,28. This critical issue is largely being overlooked due to the country’s limited resources for tackling all aspects of drug use and trafficking. Therefore, findings from this study provide an important insight into the scope and dynamics of chemsex practices, thus indicating the need to develop targeted interventions to address this emerging phenomenon among Nepali GBMSM.

Our study found that people with higher education were less likely to engage in chemsex. Similar findings have been reported in other GBMSM studies29. Individuals with higher education have better access to information and resources, making them more aware of the consequences of chemsex practices and, therefore, less likely to engage in them29. Additionally, educated individuals generally have access to quality healthcare, enhanced health knowledge, and better employment opportunities30. This leads to a broader set of social and psychological resources that promote healthy behaviors, thereby reducing the likelihood of engaging in harmful practices like chemsex. In countries like Nepal, school-based interventions like Good Behavior Game are required, which is a classroom-based behavior management strategy and has been found to positively influence drug abuse31,32. Good behavior games were shown to be cost-beneficial and found to reduce drug abuse by 37% in the age group 19–21 years old33, which could be an effective measure to reduce chemsex practice.

Our findings unveiled that a considerable proportion of chemsex-involved GBMSM in our sample faced several vulnerabilities to HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), such as condomless sex, multiple sex partners, and group/party sex. Worsening the concern of sexual risk is the increased odds of having engaged in multiple sex partners and group/party sex among GBMSM who engage in chemsex, which is consistent with existing literature1,24. Drugs used for chemsex can increase sexual disinhibition and affect sexual decision-making, leading to risky sexual behaviors1,23,34,35. These behaviors are significant risk factors for HIV and other STIs13,23,35,36. Considering this potentially devastating syndemic, with the emerging phenomenon of chemsex in Nepal and its association with risk-taking behaviors, addressing chemsex as a critical public health priority is imperative.

Notably, an important contribution of our study is the observed association between engagement in chemsex and mental health among GBMSM. Specifically, GBMSM who experienced depressive symptoms had higher odds of being involved in chemsex practices, which is in line with prior findings18,34,37. The relationship between chemsex and mental health outcomes is complex, with ambiguous directionality between these factors. For example, individuals with depression may turn to chemsex as a maladaptive coping mechanism to overcome psychological distress, internalized homonegativity, or social isolation18. The substances commonly used in chemsex, such as methamphetamine, GHB/GBL, and ketamine, can produce feelings of euphoria, increased sexual arousal, and temporary relief from emotional distress. These effects might be particularly appealing to those suffering from depressive symptoms38, offering a temporary escape from their negative emotions and enhancing their social and sexual experiences. On the other hand, chronic involvement in chemsex activities can also contribute to the onset of depressive symptoms1,12,29,39,40,41,42.

Overall, these findings can inform the development and implementation of tailored interventions like leveraging digital health technologies and peer-led approaches to address risks associated with engagement in chemsex among GBMSM. Existing research has shown that chemsex-involved GBMSM face stigma and discrimination, even in healthcare settings35,43. In recent years, the use of geosocial networking apps (e.g., Grindr, Hornet) has significantly been associated with increased sexualized drugs44. This might be because these applications make chemsex more acceptable and easier to access. For marginalized groups like GBMSM, they provide a sense of connection and encourage unhealthy ways of coping, as chemsex is sometimes used to feel close to others and have longer sexual experiences. Given the high prevalence of smartphone ownership and preference for digital health interventions in Nepali GBMSM45, using such technology can provide a private, anonymous, and easily accessible platform to offer supportive care and useful information on chemsex practices46. These technologies might help users in timely referral and linkage with trained LGBT-friendly providers or sexual health clinics, addressing syndemic health challenges such as sexuality, mental health, and chemsex-related stigma in clinical settings that serve GBMSM, which are culturally competent, sensitive, and stigma-free. Furthermore, peer support is also protective for health who can be educated about the breadth of chemsex experiences, and support beyond medicalized model of care. Harm reduction services delivered by peers are perceived as more influential47. Therefore, peer-led and digital health service delivery models may be an effective harm reduction strategy for GBMSM engaged in chemsex.

The strength of this study is that it includes a large sample of GBMSM, which is the first of its kind in Nepal. Despite its strength, there are some limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, results are based on self-reported data, which might have introduced recall and social desirability biases. Second, associations between chemsex, sexual risk behavior, and mental health problems have been demonstrated; these results cannot be interpreted as causal relationships. Third, we failed to ask the name of the drugs and generalized all at once; it could be insightful to look at the distribution of chemsex drugs. Fourth, this research lacks data concerning when or why these drugs are being used. Fifth, since it was an online survey and participants were recruited from convenience sampling, there was a high nonresponse rate, and this study was not able to include the representatives based on ethnicities, provinces, and ages even if we did our study with a large population. Finally, the study was done only with the participants who have access to smartphones or computers since it is an online survey which might have resulted in selection bias. Therefore, participants who did not have access to mobile phones were excluded. This might have resulted in different findings. Furthermore, longitudinal studies using ecological momentary assessment could be performed to confirm our results and the results of other similar studies.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the prevalence and factors associated with chemsex practices among GBMSM in Nepal, a group that already faces substantial societal marginalization. The findings indicated an emerging phenomenon of chemsex practices, with high prevalence, among GBMSM in Nepal. The engagement in chemsex practices was associated with increased sexual risk-taking behaviors, including multiple sex partners and party or group sex, and mental health issues. Therefore, there is an urgent need for an integrated approach encompassing awareness raising, drug use support, sexual health services, and mental health care. This approach should prioritize harm reduction strategies specifically tailored for GBMSM engaged in chemsex practices.

Methods

Study design and participants

A nationwide cross-sectional online survey was conducted between March and May 2024 to assess the chemsex practices among Nepali GBMSM. The eligibility criteria of the study included: (1) being 18 years or older, (2) being a cisgender male who has sex with men, and (3) being able to read and understand Nepali or English.

Study procedures

GBMSM were recruited through convenience sampling via social networking websites such as Facebook and Instagram. We posted recruitment flyers on the social media pages of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and community-based organizations (CBOs) such as the Blue Diamond Society (BDS), a non-governmental (NGO) community-based organization working for the rights of Nepal’s marginalized gay, transgender, and other sexual minority communities. Interested individuals who clicked on the flyer were directed to an eligibility self-screening tool and a brief online consent form hosted by Qualtrics. Each eligible participant completed an online consent form by acknowledging that they understood the purpose, risks, and benefits of the study prior to completing the survey. The survey took approximately 15 min to complete, and participants received compensation of NRS 400 (~ USD 3).

We followed established protocols for identifying and eliminating potential duplicate cases48. Specifically, possible duplicates were identified based on commonalities in age, sexual orientation, and ethnicity. All the cases with similar characteristics were examined manually by focusing on responses to other questions, such as educational level, relationship status, device and browser information, and completion duration.

During the two-month recruitment period, 1256 responses were received. Of those, 1,177 met the inclusion criteria and consented to participate in the survey. Of the 1,177 who started the survey, 335 were excluded (incomplete responses: 331; outside of Nepal: (4), thus leaving the final analytic sample at 842.

Ethical considerations

The Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC) approved the study protocol and consent form (30/2024). Research was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration, and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines.

Measures

The primary outcome variable for this study is recent engagement in chemsex, which is defined as the use of any psychoactive substance like crystal methamphetamine, mephedrone, GHB/GBL before or during sexual activity in the last 12 months.

We included participants’ demographic characteristics, psychosocial factors, and recent sexual and health-related behaviors as independent variables.

Demographic characteristics

The participants’ demographic characteristics include age (< 25 years and ≥ 25 years), current residing province, educational level (less than high school/ Proficiency Certificate Level (PCL) and high school/PCL or above), ethnicity (Dalit, Janajati, Madhesi, Brahmin/Chhetri, others), sexual orientation (gay, bisexual, and other MSM), and relationship status (single and with partner).

Psychosocial factors

We assessed the participant’s experience of depressive symptoms in the past two weeks using the nine-item Patients Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). This scale scores between 0 to 27, and participants who scored greater than 9 were considered to have depressive symptoms49. Additionally, we assessed the utilization of mental health services by asking if they have seen a mental health care provider in the last 12 months (Yes, No, but I needed to, and No, because I did not need to). The social support level was assessed using the three-item Oslo Social Support Scale (OSS-3). The OSS score (range: 3–14) was categorized as poor (3–8), moderate (9–11), and strong (12–14)50.

Sexual and health-related behaviors

We assessed participants’ recent engagement in various sexual and HIV-related behaviors. Participants were asked about their sexual behaviors within the 12 months, such as engagement in anal sex with another man, condomless sex, multiple sex partners, and transactional sex (received money or goods like food, cigarettes, and drugs in return for sex in the last 12 months). Additionally, we assessed various health-related variables, including HIV testing practices, HIV status, and smoking status.

Smartphone use and internet access

We evaluated participants’ access to a smartphone (Yes, No) and their daily internet usage (Yes, No).

Data analysis

Data from Qualtrics were automatically recorded in CSV format. All the collected information was systematically compiled, coded, checked, and edited on the same day of the data collection. Analysis was done using STATA version 18.0 (Stata Corp, Texas, USA).

Descriptive analysis was performed by calculating frequencies for categorical variables. The Chi-square test was performed to determine the association between dependent and independent categorical variables. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine potential factors associated with the variable of interest, and an adjusted odds ratio at 95% confidence intervals was calculated. Variables that showed significance at a 10% level in the bivariate analysis were included in multivariable logistic regression. The regression model allowed for the adjustment of the multiple variables, thus controlling the potential confounding variables. The variance inflation factor was calculated before fitting into the model.

Data availability

The data used during this study will be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Pufall, E. L. et al. Sexualized drug use (‘chemsex’) and high-risk sexual behaviours in HIV-positive men who have sex with men. HIV Med. 19, 261–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/hiv.12574 (2018).

Kong, T. S. K. & Laidler, K. J. The paradox for chem-fun and gay men: a neoliberal analysis of drugs and HIV/AIDS policies in Hong Kong. J. Psychoactive Drugs 52, 77–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2019.1568648 (2020).

Barbier, J. Chemsex. Insistance 13, 189–204. https://doi.org/10.3917/insi.013.0189 (2018).

Wang, H., Jonas, K. J. & Guadamuz, T. E. Chemsex and chemsex associated substance use among men who have sex with men in Asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 243, 109741–109741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109741 (2023).

Malandain, L. et al. Chemical sex (chemsex) in a population of French university students. Dial. Clin. Neurosci. 23, 39–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/19585969.2022.2042163 (2021).

Giorgetti, R. et al. When “Chems” meet sex: a rising phenomenon called “ChemSex”. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 15, 762–770. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159X15666161117151148 (2017).

Glyde, T. Chemsex exposed. Lancet (Br. Ed.) 386, 2243–2244. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01111-3 (2015).

Drückler, S., van Rooijen, M. S. & de Vries, H. J. C. Chemsex among men who have sex with men: a sexualized drug use survey among clients of the sexually transmitted infection outpatient clinic and users of a gay dating app in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Sex. Transm. Dis. 45, 325–331. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000753 (2018).

del Pozo-Herce, P. et al. Descriptive study on substance uses and risk of sexually transmitted infections in the practice of Chemsex in Spain. Front. Public Health 12, 1391390–1391390. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1391390 (2024).

Maxwell, S., Shahmanesh, M. & Gafos, M. Chemsex behaviours among men who have sex with men: a systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Drug Policy 63, 74–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.11.014 (2019).

von Hammerstein, C. & Billieux, J. Sharpen the focus on chemsex. Addict. Behav. 149, 107910–107910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2023.107910 (2024).

Hegazi, A. et al. Chemsex and the city: sexualised substance use in gay bisexual and other men who have sex with men attending sexual health clinics. Int. J. STD AIDS 28, 362–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956462416651229 (2017).

Daskalopoulou, M. et al. Condomless sex in HIV-diagnosed men who have sex with men in the UK: prevalence, correlates, and implications for HIV transmission (2017). https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2016-053029.

D’Silva, A. Beware the possible dangers of chemsex—is illicit drug-related sudden cardiac death underestimated?. JAMA Cardiol. 7, 1080–1081. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2022.2207 (2022).

Lim, S. H., Akbar, M., Wickersham, J. A., Kamarulzaman, A. & Altice, F. L. The management of methamphetamine use in sexual settings among men who have sex with men in Malaysia. Int. J. Drug Policy 55, 256–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.02.019 (2018).

Digiusto, E. & Rawstorne, P. Is it really crystal clear that using methamphetamine (or other recreational drugs) causes people to engage in unsafe sex?. Sexual Health 10, 133–137. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH12053 (2013).

Íncera-Fernández, D., Román, F. J. & Gámez-Guadix, M. Risky sexual practices, sexually transmitted infections, motivations, and mental health among heterosexual women and men who practice sexualized drug use in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 6387. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116387 (2022).

Moreno-Gámez, L., Hernández-Huerta, D. & Lahera, G. Chemsex and psychosis: a systematic review. Behav. Sci. 12, 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12120516 (2022).

Lund, E. M. & Burgess, C. M. Sexual and gender minority health care disparities. Primary Care 48, 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pop.2021.02.007 (2021).

Oestreich, J. E. Sexual orientation and gender identity in Nepal: rights promotion through UN development assistance. J. Human Rights 17, 265–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/14754835.2017.1357028 (2018).

Sanders, S. & Dickson, S. India, Nepal, and Pakistan: a unique South Asian constitutional discourse on sexual orientation and gender identity. In Social Difference and Constitutionalism in Pan-Asia (ed. Williams, S. H.) 316–348 (Cambridge University Press, 2012). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139567312.017.

Chone, J. S. et al. Factors associated with chemsex in portugal during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rev. Latino-americana Enfermagem 29, e3474–e3474. https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.4975.3474 (2021).

Amundsen, E., Haugstvedt, Å., Skogen, V. & Berg, R. C. Health characteristics associated with chemsex among men who have sex with men: results from a cross-sectional clinic survey in Norway. PloS one 17, e0275618. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275618 (2022).

Maviglia, F. et al. Engagement in chemsex among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Malaysia: prevalence and associated factors from an online national survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20, 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010294 (2022).

Mao, X. et al. Use of multiple recreational drugs is associated with new HIV infections among men who have sex with men in China: a multicenter cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 21, 354–354. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10223-y (2021).

Wong, N. S., Kwan, T. H., Lee, K. C. K., Lau, J. Y. C. & Lee, S. S. Delineation of chemsex patterns of men who have sex with men in association with their sexual networks and linkage to HIV prevention. Int. J. Drug Policy 75, 102591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.10.015 (2020).

Singh, K. M. Nepal introduces tough drug laws. Far Eastern Econ. Rev. 134, 10 (1986).

Prasad, P. et al. Adherence of drug promotional literatures distributed by pharmaceutical companies to world health organization ethical criteria for medicinal drug promotion. J. Nepal Health Res. Council 17, 345–350. https://doi.org/10.33314/jnhrc.v17i3.1840 (2019).

Sewell, J. et al. Changes in chemsex and sexual behaviour over time, among a cohort of MSM in London and Brighton: findings from the AURAH2 study. Int. J. Drug Policy 68, 54–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.03.021 (2019).

Zajacova, A. & Lawrence, E. M. The relationship between education and health: reducing disparities through a contextual approach. Annu. Rev. Public Health 39, 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044628 (2018).

Bowman-Perrott, L., Burke, M. D., Zaini, S., Zhang, N. & Vannest, K. Promoting positive behavior using the good behavior game: a meta-analysis of single-case research. J. Positive Behavior Intervent. 18, 180–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300715592355 (2016).

Kellam, S. G. et al. The good behavior game and the future of prevention and treatment. Addict. Sci. Clin. Pract. 6, 73–84 (2011).

Kendler, K. S. et al. Academic achievement and drug abuse risk assessed using instrumental variable analysis and co-relative designs. JAMA Psychiatry 75, 1182–1188. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2337 (2018).

Strasser, M., Halms, T., Rüther, T., Hasan, A. & Gertzen, M. Lethal lust: suicidal behavior and chemsex—a narrative review of the literature. Brain Sci. 13, 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13020174 (2023).

Strong, C. et al. HIV, chemsex, and the need for harm-reduction interventions to support gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. Lancet HIV 9, e717–e725. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(22)00124-2 (2022).

Glynn, R. W. et al. Chemsex, risk behaviours and sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men in Dublin, Ireland. Int. J. Drug Policy 52, 9–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.10.008 (2018).

Hibbert, M. P., Brett, C. E., Porcellato, L. A. & Hope, V. D. Psychosocial and sexual characteristics associated with sexualised drug use and chemsex among men who have sex with men (MSM) in the UK. Sex. Trans. Infect. 95, 342–350. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2018-053933 (2019).

Weiss, R. D., Griffin, M. L. & Mirin, S. M. Drug abuse as self-medication for depression: an empirical study. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 18, 121–129. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952999208992825 (1992).

Lee, M. et al. O11 Chemsex and the city: sexualised substance use in gay bisexual and other men who have sex with men. Sex. Trans. Infect. 91, A4–A4. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2015-052126.11 (2015).

Kurtz, S. P. Post-circuit blues: motivations and consequences of crystal meth use among gay men in Miami. AIDS Behavior 9, 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-005-1682-3 (2005).

McCarty-Caplan, D., Jantz, I. & Swartz, J. MSM and drug use: a latent class analysis of drug use and related sexual risk behaviors. AIDS Behavior 18, 1339–1351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0622-x (2014).

Dearing, N. & Flew, S. P211 Msm the cost of having a good time? A survey about sex, drugs and losing control. Sex. Transm. Infect. 91, A86–A86. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2015-052126.255 (2015).

Hung, Y. R. et al. Utilization of mental health services in relation to the intention to reduce chemsex behavior among clients from an integrated sexual health services center in Taiwan. Harm Reduct. J. 20, 52–52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-023-00777-y (2023).

Gibson, L. P., Kramer, E. B. & Bryan, A. D. Geosocial networking app use associated with sexual risk behavior and pre-exposure prophylaxis use among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men: cross-sectional web-based survey. JMIR Form. Res. 6, e35548–e35548. https://doi.org/10.2196/35548 (2022).

Gautam, K. et al. High interest in the use of mHealth platform for HIV prevention among men who have sex with men in Nepal. J. Commun. Health https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-024-01324-x (2024).

Choi, E. P. H. et al. Web-based harm reduction intervention for chemsex in men who have sex with men: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 9, e42902–e42902. https://doi.org/10.2196/42902 (2023).

Katz, S. J., Cohen, E. & Hatsukami, D. Testing the influence of harm reduction messages on health risk attitudes, injunctive norms and perceived behavioral control. Harm Reduct. J. 20, 1–113. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-023-00846-2 (2023).

Teitcher, J. E. et al. Detecting, preventing, and responding to “fraudsters” in internet research: ethics and tradeoffs. J. Law Med. Ethics 43, 116–133. https://doi.org/10.1111/jlme.12200 (2015).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. W. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gener. Internal Med. 16, 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x (2001).

Kocalevent, R.-D. et al. Social support in the general population: standardization of the Oslo social support scale (OSSS-3). BMC Psychol. 6, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-018-0249-9 (2018).

Funding

We acknowledge financial support in part from a career development award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K01 DA051346) to Dr. Roman Shrestha. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, manuscript preparation, or the decision to publish.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RS, KP and KG conceptualized and conducted the research. KP and RS performed the statistical analysis. KP prepared the first draft of the manuscript by taking the subsequent help of RS, AP, PB, and KG. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and provided insightful input. RS supervised the study. All authors read, reviewed, and agreed to the last version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Paudel, K., Gautam, K., Pandey, A. et al. Prevalence of chemsex and associated factors among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in Nepal: findings from an online national survey. Sci Rep 15, 23087 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92449-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92449-z