Abstract

To evaluate the pathological and clinical course differences between bucillamine‑induced membranous nephropathy (BCL-MN) and primary membranous nephropathy (p-MN). This retrospective cohort study included 29 BCL-MN patients and 98 p-MN patients at two hospitals from 2000 to 2019. We compared the kidney biopsy findings and clinical course between the BCL-MN and p-MN groups, focusing on pathological differences, proteinuria relapse rates, and 30% or greater decrease in the eGFR. While kidney function and proteinuria levels were similar, histopathological differences were observed. BCL-MN group showed less spike formation in LM and more stage I cases. IgG1 was predominant in BCL-MN group, contrasting with IgG4 in p-MN group. BCL-MN group had significantly higher prevalence of segmental subepithelial deposits (66.7% vs. 24.7%, p < 0.001) and para-mesangial deposits (61.5% vs. 18.1%, p < 0.001). Notably, foot process effacement in areas without dense deposits was more common in BCL-MN (96.3% vs. 4.6%, p < 0.001). Clinically, the majority of patients in the BCL-MN group experienced proteinuria resolution after 1 year of drug discontinuation alone, and there was no progression of renal function decline. BCL-MN differs from p-MN both histologically and clinically, which may be related to the mechanism induced by BCL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Membranous nephropathy (MN) is characterized by granular deposition of IgG in the glomerular basement membrane (GBM). IgG subclass evaluation helps differentiate primary from secondary MN (s-MN), with IgG4 predominance being a feature of primary MN1. Beck et al. identified the M-type phospholipase A2 receptor (PLA2R) as a podocyte antigen marker for primary MN (p-MN)2. Moroni et al. reported that secondary MN is caused by infections, drugs, and malignancies, with predominant IgG1, IgG2, and IgG3 staining rather than IgG4 staining. Drug-induced MN is often reversible upon discontinuation of the offending agent, with complete recovery of renal function in many cases3, and gold and D-penicillamine, which are used for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) treatment, are known to cause drug-related s-MN4. Nagahama et al. first reported that bucillamine (BCL), which is widely used in Japan for RA, also causes s-MN5. They noted IgG1 predominance, low spike formation frequency, localized IgG staining via immunofluorescence (IF), and early stage MN with segmentally distributed subepithelial dense deposits via electron microscopy (EM). Regarding the clinical course characteristics of BCL-MN, Hoshino et al. reported that discontinuing BCL is the most effective intervention, whereas prednisolone or other immunosuppressants may not be effective6. Although the frequency of BCL-MN is reportedly high in Japan, detailed information on its pathological evaluation and long-term prognosis compared with those of primary MN is lacking7,8.

In the present study, we compared the pathological features and clinical outcomes of 29 patients with BCL-MM and 98 patients with p-MN via kidney biopsies from two institutions to elucidate their distinctive characteristics.

Methods

Study design and population

A retrospective cohort study was conducted to compare the pathological and clinical characteristics of patients with BCL-MN and p-MN. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, Toranomon Hospital reviewed waived the need of obtaining informed consent. The study included patients diagnosed with MN on initial kidney biopsy at Toranomon Hospital (Tokyo, Japan) or Toranomon Hospital Kajigaya (Kanagawa, Japan) between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2020. We limited our study to patients diagnosed with MN on initial kidney biopsy. Primary MN was confirmed through biopsy findings and the exclusion of secondary causes4. The diagnosis of BCL- MN was established based on kidney biopsy findings, coupled with the characteristic clinical course in a patient diagnosed with RA, including the onset of proteinuria following BCL therapy5,6. RA diagnosis followed the American College of Rheumatology’s 1987 revised criteria9. All the BCL-MN patients were RA patients, whereas the p-MN group had no RA patients. The key diagnostic indicators for BCL-MN include proteinuria onset following BCL treatment and its resolution upon discontinuation6. The exclusion criteria included cases lacking data on age, sex, or IF studies; those with concomitant glomerulonephritis; and those with s-MN except for BCL-MN. The majority of the study population, which mainly lived in the Tokyo metropolitan area, was under the care of each hospital or its satellite clinics every 1–3 months.

Data collection and variables

Clinical data, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), the urine protein-to-creatinine ratio (UPCR), and RA duration (for BCL-MN), were collected from medical records at the time of kidney biopsy. The nephrotic range of proteinuria was defined as ≥ 3.5 g/gCre. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated via a Japanese-specific formula10. Hypertension was defined by antihypertensive medication use. The use of medications, including renin‒angiotensin system (RAS) blockers, glucocorticoids, methotrexate, and biologics, was noted for BCL-MN patients.

Kidney biopsy samples were subjected to standard analysis via light microscopy (LM), IF, and EM11. IgG deposition patterns were classified as “diffuse” or “focal”. IgG1/IgG4 predominance was categorized as “IgG1 > IgG4”, “IgG1 = IgG4”, or “IgG1 < IgG4”. Multiple pathologists, at least two experts, independently evaluated each sample.

The proportion of globally sclerosed glomeruli and the occurrence of segmental glomerulosclerosis were assessed. Additionally, we assessed biopsies for the occurrence of segmental glomerulosclerosis. The severity of arteriosclerosis was graded as 0 or 1 (Grade 0: intimal thickening < thickness of media; Grade 1: intimal thickening ≥ media thickness)12. Tubulointerstitial damage (IF/TA) was graded as follows: Grade 0 (< 10%), Grade 1 (10–25%), Grade 2 (26–50%) or Grade 3 (> 50%)13.

GBM alterations were classified into stages I-IV according to the Ehrenreich and Churg criteria14 or on the basis of previous reports of patients without EM15. The immunofluorescence intensity in the glomerular capillary tufts and mesangial areas was graded as follows: –, ±, 1+, 2+.

Treatment analysis categorized patients on the basis of postbiopsy medication changes. The “no medication” group had no new or increased treatments. The “GC” group received new or increased glucocorticoids. The “CI” group was given calcineurin inhibitors. This classification allows the assessment of different treatment approaches following kidney biopsy.

For prognostic analysis, UPCR was categorized into four grades: <0.3, 0.3–<1.0, 1.0–<3.5, and ≥ 3.5 g/gCr. Relapse was defined as initiating or increasing the use of glucocorticoids or immunosuppressants due to increased proteinuria. The kidney endpoint was established as a ≥ 30% decrease in kidney function. These criteria allowed for a comprehensive evaluation of disease progression and treatment outcomes.

The outcomes

Primary outcome: pathological differences between p-MN and BCL-MN.

Secondary outcomes: Relapse-free and kidney endpoint-free survival rates.

Data analysis

All patients were categorized into p-MN and BCL-MN groups. Baseline clinical and pathological characteristics were summarized using median values with interquartile ranges for continuous variables, whereas categorical variables are presented as percentages. For statistical comparisons, Wilcoxon, Kruskal‒Wallis, and Fisher’s exact tests were used. The MN stage distribution was analyzed via ordinal logistic regression. Both crude and adjusted analyses were conducted, with the latter controlling for time from presentation to biopsy and UPCR. Clinical course differences were evaluated by comparing 24-month relapse rates and kidney endpoints. Kaplan‒Meier analysis generated survival curves, whereas Cox proportional hazards models estimated HRs and 95% CIs, adjusting for sex and proteinuria factors previously associated with relapse risk in p-MN, which may influence the relapse rate16,17. Additionally, given the reported associations of sex, age ≥ 60 years, serum albumin < 2.5 g/dL, and IFTA with renal prognosis in p-MN17, these variables were included as covariates in multivariate analyses of kidney endpoints.

All analyses were performed using STATA software version 16.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Stone, TX, USA).

Results

Study flowchart and selection of the study population

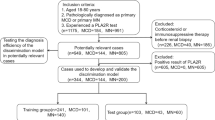

Of the 189 initial patients, 62 were excluded: 11 for lack of IF, 18 for coexisting glomerulonephritis, and 39 for s-MN other than BCL-MN. The final analysis included 127 cases: 98 p-MN and 29 BCL-MN. Figure 1 illustrates the study flow and population selection process.

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the patients. The median time from presentation to biopsy was 200 days for p-MN patients and 126 days for BCL-MN patients, with no significant difference between the groups. BCL-MN had more females and greater glucocorticoid use, whereas p-MN had more hypertension and ACE/ARB use. The UPCR rate and frequency of nephrotic-range proteinuria were not significantly different between the p-MN and BCL-MN groups. Serum PLA2R antibodies were tested in 38 patients (38.8%) in the p-MN group, with 11 positive results (29.7%). In the BCL-MN group, 6 patients (20.7%) were tested, all of whom yielded negative results.

LM findings

LM revealed significant differences in stage distribution between p-MN and BCL-MN patients (Table 2A), and BCL-MN patients were predominantly in stage I (72.4%). Ordinal logistic regression indicated that BCL-MN had significantly lower odds of being in higher stage categories compared with p-MN (OR = 0.14; 95% CI: 0.05–0.37; p < 0.001). This association remained significant after adjusting for time from disease onset to kidney biopsy and the urine protein-to-creatinine ratio (adjusted OR = 0.11; 95% CI: 0.04–0.27; p < 0.001) (Table 2B). These findings suggest distinct pathological progression patterns between p-MN and BCL-MN, with BCL-MN being more likely to be at earlier stages. The median percentages of global sclerotic glomeruli were similar in the p-MN (9.2%) and BCL-MN (6.5%) groups. The frequency of mild to moderate mesangial proliferation was comparable (10% vs. 14%). Most patients in both groups presented with no or mild interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (IFTA), with no significant difference in atherosclerotic lesions. However, focal segmental sclerosis lesions were significantly more prevalent in the p-MN group (p = 0.022). Figure 2A shows a kidney biopsy sample with PAM staining from a patient diagnosed with BCL-MN. This image reveals no spike formation in the GBM. In contrast, Fig. 2F depicts a kidney biopsy sample from a patient diagnosed with p-MN, showing spike formation in the GBM.

Kidney biopsy specimens from patients diagnosed with both BCL-MN and p-MN. BCL-MN. (A) LM shows intact glomeruli, and there is no spike formation in the GBM. (B) IF, IgG shows granular stain along the GBM, but the distribution of deposition (arrow) was segmental. (C) IgG1 shows positive staining. (D) IgG4 shows negative staining. (E) EM image showing segmental deposition of the subepithelial EDD (large arrow). Foot process effacement (red arrow) is observed in areas both with subepithelial EDD (small arrow) and without or with a small amount of subepithelial EDD. Primary-MN. (F) LM shows spike formation in the GBM. (G) IF revealed diffuse granular deposition of IgG (arrow) in the GBM. (H) IgG1 negative staining in the glomeruli. (I) IgG4-positive staining along the GBM (arrow). (J) EM image showing a diffusely distributed EDD (arrow) in the subepithelial region of the GBM.

Data are expressed as the median (25–75th percentiles) or number of patients (percentage).

MN: Membranous Nephropathy, IFTA: Interstitial Fibrosis and Tubular Atrophy, UPCR: Urinary Protein-to-Creatinine Ratio,

IF findings

In one BCL-induced MN patient, glomerular IgG deposition was negative, but spike lesions and subepithelial deposits were confirmed by light and electron microscopy. All other MN patients presented with glomerular IgG deposition. Table 3A shows the IF findings. The BCL-MN group presented a greater prevalence of segmental IgG deposition (43% vs. 1%, p < 0.001; Table 3A) and a greater prevalence of “IgG1 > IgG4” subclass predominance (52% vs. 26%, p = 0.027; Table 3B). No significant differences in IgA, IgM, C3, C4, or C1q deposition levels were observed between the p-MN and BCL-MN groups. Figure 2B and C, and 1D show kidney biopsy samples from a patient diagnosed with BCL-MN, as examined by IF. These images demonstrate a segmental distribution of IgG along the GBM, positive staining for IgG1, and negative staining for IgG4. In contrast, Fig. 2G and H, and 2I present kidney biopsy samples from a patient diagnosed with p-MN. These images show a diffuse distribution of IgG along the GBM, negative staining for IgG1, and positive staining for IgG4.

EM findings

Electron microscopy was performed on 74 out of 98 cases (75%) in the p-MN group and 27 out of 29 cases (93%) in the BCL-MN group. Table 3C compares the EM features between the groups. BCL-MN presented a significantly greater prevalence of segmental subepithelial deposits (66.7% vs. 24.7%, p < 0.001) and subendothelial dense deposits (61.5% vs. 18.1%, p < 0.001). Notably, foot process effacement in areas without dense deposits was markedly more common in the BCL-MN (96.3% vs. 4.6%, p < 0.001). Conversely, p-MN presented a greater prevalence of intramembranous deposits (54.7% vs. 3.7%, p < 0.001) and lucent areas (44.0% vs. 7.4%, p = 0.001) compared with BCL-MN. Figure 2E shows an EM image of a BCL-MN kidney biopsy sample, which revealed dense segmental subepithelial deposits. In contrast, Fig. 2J presents a p-MN kidney biopsy with diffusely distributed dense deposits. These images illustrate the distinct ultrastructural features of BCL-MN and p-MN.

Treatment and outcomes

Table 4A shows that fewer BCL-MN patients than p-MN patients received additional glucocorticoid treatment (6.9% vs. 25.5%, p = 0.03). However, one year postbiopsy, a significantly greater proportion of BCL-MN patients achieved a UPCR of < 0.3 g/gCre (63.2% vs. 35.6%, p = 0.038), as shown in Table 4B.

Prognostic analysis

Relapse-free survival rate and kidney endpoint-free survival

K‒M survival curves revealed significant differences in relapse-free survival rates between the BCL-MN and p-MN groups. The 24-month relapse-free survival rate was greater in the BCL-MN group (55.3% vs. 40.5%, p = 0.02) (Fig. 3A). However, the difference in kidney endpoint-free survival rates at 24 months was not statistically significant (BCL-MN: 73.5% vs. p-MN: 70.1%, p = 0.34) (Fig. 3B).

Table 5A shows the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for relapse in BCL-MN patients compared with p-MN patients. The unadjusted HR was 0.09 (95% CI: 0.01–0.69), indicating a significantly lower relapse risk in patients with BCL-MN. After adjusting for known risk factors, the HR remained significant at 0.08 (95% CI: 0.01–0.60). Table 5B shows the HRs and 95% CIs for the associations between BCL-MN and kidney endpoints. Table 5B shows the HRs for the kidney endpoints. The unadjusted HR for BCL-MN was 0.50 (95% CI: 0.17–1.45), which was not statistically significant. After adjustment, it remained nonsignificant at 0.55 (95% CI: 0.18–1.66). The only significant risk factor for kidney endpoints was serum albumin < 2.5 g/dL (HR: 2.69; 95% CI: 1.25–5.78; p = 0.01).

Discussion

This study revealed pathological and clinical course differences between BCL-MN and p-MN patients and compared their clinical outcomes directly. These findings provide new insights into the distinctions and prognoses of these conditions.

Moroni et al. suggested that s-MN represents an early stage of MN, as proteinuria emerges during the progression of the underlying disease, enabling early detection of kidney involvement4.

Nagahama et al. analyzed BCL-MN in six RA patients and revealed early-stage lesions with minimal spike formation, segmental subepithelial dense deposits, segmental IgG deposition, and IgG subclass staining beyond IgG4. These characteristics, which are atypical in p-MN, are considered indicative of s-MN5. Additionally, Kaga et al. compared 12 p-MN cases with 6 BCL-MN cases via immunofluorescence. They reported IgG4 deposition in p-MN, whereas both IgG4 and IgG1 deposition was detected in BCL-MN18. Despite these insights, few large-scale studies have examined the pathological distinctions between BCL-MN and p-MN. This gap in research highlights the need for more comprehensive investigations to better understand these conditions.

In this study, LM revealed no significant differences in mesangial proliferation between p-MN and BCL-MN. However, BCL-MN showed fewer focal segmental glomerulosclerosis lesions and spikes, with a higher frequency of early-stage cases, independent of disease duration and proteinuria levels. This greater prevalence of early-stage cases in patients with BCL-MN persisted even after adjusting for disease duration and proteinuria levels, suggesting a potentially distinct pathophysiology compared with that in patients with p-MN. IF studies demonstrated mild IgG deposition with frequent segmental capillary loop distribution in BCL-MN. Additionally, BCL-MN exhibited a predominant “IgG1 > IgG4” pattern compared to p-MN, suggesting distinct pathophysiological mechanisms between drug-induced and primary forms of MN.

p-MN is characterized by IgG4 dominance and PLA2R antibodies, while s-MN associated with autoimmune diseases and hepatitis typically shows IgG1-dominant deposits, as demonstrated in 60% of s-MN cases19. Although this report does not include BCL-MN cases, Our findings may suggest that BCL-MN shares pathogenic features with s-MN associated with autoimmune diseases and infections, rather than p-MN. Notably, in the present study, no PLA2R antibody-positive cases were observed in the BCL-MN group.

We noted that, compared p-MN, BCL-MN showed segmental distribution of deposits. While foot process effacement in p-MN occurs near diffuse subepithelial deposits, BCL-MN demonstrated extensive effacement even in areas with minimal or no deposits. Based on mouse model evidence showing BCL’s direct effect on podocyte foot processes20, these findings suggest that BCL may induce both immune complex formation and direct podocytopathy in humans.

Numerous target antigens for MN, such as PLA2R, THSD7A, and NELL-1, have become relatively accessible in pathological diagnostics21. Recently, Miyazaki et al. reported that among four cases of NELL-1-positive membranous nephropathy associated with RA, three cases were induced by BCL therapy22. Although NELL-1 staining was not performed in our study, our findings were consistent with their report in that two out of three BCL-MN cases showed segmental distribution of deposits, and proteinuria decreased after BCL discontinuation in two cases. NELL-1 staining in BCL-MN cases remains a future research priority.

We performed a comprehensive investigation using widely available, routinely measured, clinically applicable methods to differentiate between biopsy-confirmed BCL-MN and p-MN. Our findings demonstrated that BCL-MN exhibits distinct pathological characteristics, including segmental IgG deposition, IgG1 subclass predominance, and early MN stage even after adjusting for the time of onset. While recently identified target antigens show promise as diagnostic markers, they are not yet readily accessible for routine clinical use.

Regarding the clinical course of BCL-MN, Hoshino et al.6 and Obayashi et al.23 analyzed 17 and 10 biopsy-proven BCL-MN cases, respectively, and both studies reported that all patients achieved proteinuria remission without renal function loss after BCL discontinuation. They concluded that stopping BCL was the most crucial intervention, suggesting the limited efficacy of immunosuppressants in managing this condition. Our study directly compared the BCL-MN and p-MN groups, revealing a significantly greater prevalence of patients without medication in the BCL-MN group. Additionally, the frequency of patients with a UPCR < 0.3 g/gCre one year post-kidney biopsy was significantly greater in the BCL-MN group. These results support Hoshino et al.‘s findings and further elucidate the distinct clinical course of BCL-MN compared with p-MN.

Our study showed higher relapse-free survival compared to the p-MN group, Consistent with previous studies6 indicating that BCL discontinuation is the primary effective treatment. Although one patient experienced relapse after BCL discontinuation, the absence of kidney biopsy made it difficult to distinguish between BCL-MN recurrence and coexisting nephritis. The kidney endpoint-free survival rate was not significantly different between the BCL-MN and p-MN groups. Serum Alb levels below 2.5 g/dL at biopsy emerged as the sole significant risk factor for the kidney endpoint. While previous studies on p-MN prognosis identified age ≥ 60 years, serum Alb concentration, and IFTA as risk factors24, our research revealed that only the serum Alb level was significantly different. Notably, despite 63.2% of BCL-MN cases achieving complete remission within one year, kidney endpoint-free survival remained comparable between groups. This observation may be attributed to RA itself being a significant risk factor for CKD development25, with methotrexate therapy potentially contributing to kidney function deterioration26.

While BCL is commonly used as a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug in RA treatment, comprehensive studies comparing BCL-MN with p-MN have been limited. Our study addresses this knowledge gap by analyzing a substantial cohort of BCL-MN cases, enabling a thorough comparison of pathological features, treatment outcomes, and clinical courses between BCL-MN and p-MN groups. Through extended follow-up periods and adequate sample sizes, we provide the first detailed evaluation of relapse rates and kidney prognosis in BCL-MN patients. This comprehensive analysis reveals the distinct characteristics of BCL-MN versus p-MN, providing the first detailed evaluation of relapse rates and kidney prognosis in BCL-MN patients.

Despite representing the largest comparative analysis of BCL-MN to date, our study has several limitations. The relatively small sample size and retrospective design limit the generalizability of our findings. Many cases were excluded due to incomplete historical medical records and insufficient IF studies. Additionally, serum anti-PLA2R antibody testing was performed in only 38.8% of p-MN and 20.7% of BCL-MN patients, potentially affecting our assessment of relapse rates given its known role as a risk factor for disease recurrence. Nevertheless, our findings demonstrate distinct histopathological features and clinical courses between BCL-MN and p-MN, providing valuable insights that warrant validation through larger prospective studies.

Conclusions

This review affirmed its distinct characteristics, namely, segmental IgG deposition, IgG1 predominance, early MN stage, and a secondary MN course with proteinuria resolution upon drug discontinuation. Compared with p-MN patients, BCL-MN patients, despite more often remaining untreated, achieved higher rates of complete remission and lower relapse rates. Importantly, long-term kidney outcomes were comparable between the BCL-MN and p-MN groups. These findings underscore the unique features of BCL-MN in both histopathology and the clinical course. However, further research is necessary to validate these observations and elucidate the underlying mechanisms responsible for the differences in outcomes between BCL-MN and p-MN.

Data availability

Data are available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- BCL-MN:

-

Bucillamine‑induced membranous nephropathy

- p-MN:

-

Primary membranous nephropathy

- MN:

-

Membranous nephropathy

- PLA2R:

-

M-type phospholipase A2 receptor

- RA:

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

- BCL:

-

Bucillamine

- IF:

-

Immunofluorescence

- EM:

-

Electron microscopy

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- UPCR:

-

Urine protein-to-creatinine ratio

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- RAS:

-

Renin‒angiotensin system

- LM:

-

Light microscopy

- IFTA:

-

Interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DMARDs:

-

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

References

Arghiani, M. et al. A cohort study of membranous nephropathy, primary or secondary. BMC Nephrol. 22 (1), 138. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-021-02338-6 (2021).

Beck, L. H. Jr. et al. M-type phospholipase A2 receptor as target antigen in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. N Engl. J. Med. 361 (1), 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0810457 (2009).

Radford, M. G. Jr. et al. Reversible membranous nephropathy associated with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Jama 276 (6), 466–469 (1996). (In eng).

Moroni, G. & Ponticelli, C. Secondary membranous nephropathy. A narrative review. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 7, 611317. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2020.611317 (2020).

Nagahama, K. et al. Bucillamine induces membranous glomerulonephritis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 39 (4), 706–712. https://doi.org/10.1053/ajkd.2002.31987 (2002).

Hoshino, J. et al. Outcome and treatment of bucillamine-induced nephropathy. Nephron Clin. Pract. 104 (1), c15–c19. https://doi.org/10.1159/000093254 (2006).

Yokoyama, H. et al. Drug-induced kidney disease: a study of the Japan renal biopsy registry from 2007 to 2015. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 20 (5), 720–730. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-015-1201-4 (2016).

Sawamura, M. et al. Use of biologic agents and methotrexate improves renal manifestation and outcome in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a retrospective analysis. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 26 (4), 341–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-021-02160-2 (2022).

Arnett, F. C. et al. The American rheumatism association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 31 (3), 315–324. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.1780310302 (1988). (In eng).

Imai, E. et al. Estimation of glomerular filtration rate by the MDRD study equation modified for Japanese patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 11 (1), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-006-0453-4 (2007).

Ubara, Y. et al. Kidney biopsy guidebook 2020 in Japan. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 25 (4), 325–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-020-01986-6 (2021).

Kuno, H. et al. Fractional excretion of total protein predicts renal prognosis in Japanese patients with primary membranous nephropathy. Clin. Kidney J. 17 (5), sfae071. https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfae071 (2024).

Sethi, S. et al. A proposal for standardized grading of chronic changes in native kidney biopsy specimens. Kidney Int. 91 (4), 787–789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2017.01.002 (2017).

Graham, A. R. & Nagle, R. B. Quantitative electron microscopic study of membranous glomerulopathy. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 80 (6), 816–821. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/80.6.816 (1983). (In eng).

Fogo, A. B., Lusco, M. A., Najafian, B. & Alpers, C. E. AJKD atlas of renal pathology: membranous nephropathy. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 66 (3), e15–e17. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.07.006 (2015).

Caro, J. et al. Predictors of response and relapse in patients with idiopathic membranous nephropathy treated with tacrolimus. Nephrol. Dial Transpl. 30 (3), 467–474. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfu306 (2015).

Kanigicherla, D. A. et al. Long-term outcomes of persistent disease and relapse in primary membranous nephropathy. Nephrol. Dial Transpl. 31 (12), 2108–2114. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfv435 (2016).

Kaga, H. et al. Comparative proteomic analysis of glomerular proteins in primary and bucillamine-induced membranous nephropathy. Clin. Proteom. 19 (1), 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12014-022-09365-x (2022).

Huang, C. C. et al. IgG subclass staining in renal biopsies with membranous glomerulonephritis indicates subclass switch during disease progression. Mod. Pathol. 26 (6), 799–805. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2012.237 (2013).

Fujiwara, Y. et al. Proximal tubules and podocytes are toxicity targets of bucillamine in a mouse model of drug-induced kidney injury. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 670 (1), 208–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.08.051 (2011). (In eng).

Sethi, S. et al. Mayo clinic consensus report on membranous nephropathy: proposal for a novel classification. Kidney Int. 104 (6), 1092–1102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2023.06.032 (2023).

Miyazaki, R. et al. Neural epidermal growth Factor-Like 1-Positive membranous nephropathy with rheumatoid arthritis. Kidney Int. Rep. 8 (4), 921–924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2022.12.026 (2023).

Obayashi, M. et al. Clinical course of bucillamine-induced nephropathy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 7 (4), 275–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-003-0252-0 (2003).

Zhang, B. O. et al. Analysis of the prognostic risk factors of idiopathic membranous nephropathy using a new surrogate end-point. Biomedical Rep. 4 (2), 147–152. https://doi.org/10.3892/br.2015.555 (2016).

Hickson, L. J., Crowson, C. S., Gabriel, S. E., McCarthy, J. T. & Matteson, E. L. Development of reduced kidney function in rheumatoid arthritis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 63 (2), 206–213. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.08.010 (2014). (In eng).

Hayashi, K. et al. Risk of higher dose methotrexate for renal impairment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 18715. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75655-9 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by a grant for medical research from the Okinaka Memorial Institute for Medical Research, Tokyo, Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: Naoki Sawa, Yoshifumi Ubara, and Kenichi Ohashi.Data acquisition and analysis: Naoki Sawa, Kei Kono, Masayuki Yamanouchi.Manuscript drafting: Naoki Sawa, Yoshifumi Ubara, and Kenichi Ohashi. All authors have read and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This investigation adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. The ethics committee of Toranomon Hospital reviewed and approved the study (permission number: 2603-B).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sawa, N., Ubara, Y., Yamanouchi, M. et al. Bucillamine-induced membranous nephropathy versus primary membranous nephropathy: comparing pathological features and kidney prognosis. Sci Rep 15, 7869 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92465-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92465-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Bucillamine

Reactions Weekly (2025)