Abstract

Understanding the carbon sequestration potential of undisturbed and rehabilitated mangrove ecosystems is crucial for mitigating the effects of climate change. In this study, the above-ground biomass (AGB) and structural complexity of natural, rehabilitated and regenerated mangrove forest stands were investigated. Using 32 years of Landsat time series-based normalized difference infrared index data and transect field inventory methods, we examined species and structural diversity as well as AGB distribution across 24 plots spanning a gradient from sea to land. A common allometric model and linear regression analysis were used to evaluate the influence of species diversity, structural complexity, and tree density on AGB. The results revealed that natural mangrove stands exhibited higher AGB, structural complexity, and species diversity than the rehabilitated and regenerated stands. The Shannon diversity index had a negligible effect on AGB, whereas structural complexity significantly influenced AGB in natural stands. This may be attributed to the predominance of rehabilitated monoculture and less diverse scrub mangroves in natural stands. Total AGB ranged from 45.05 to 536.48 tons/ha in natural stands and from 61.57 to 98.99 tons/ha in rehabilitated stands. Our findings illustrate the challenges (e.g., high-density plantation practices, lack of species diversity, and unsuitable site conditions for planted species) associated with current rehabilitation efforts and provide insights for optimizing future rehabilitation strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mangrove ecosystems are among the most efficient biomes for carbon sequestration and storage1. They are critical for carbon sequestration and play a significant role in climate change mitigation2,3, These ecosystems provide significant ecological functions and ecosystem services, including regulating plant productivity, water filtration, breeding ground for marine habitats, fuelwood and charcoal, timber, crab and fish, and coastal protection4,5. However, mangroves face significant pressure from both anthropogenic and natural stressors6,7. Over the past 30 years, shrimp and fish farming have contributed substantially to the deforestation of mangrove forests8. Despite these challenges, mangrove ecosystems remain valuable carbon sinks, helping reduce greenhouse gas emissions2,9,10. Increasing awareness of the importance of mangrove ecosystems has spurred conservation, restoration, and rehabilitation efforts in several countries in Asia, including Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Malaysia11,12,13.

The rehabilitation and restoration of mangrove forests can often achieve multiple objectives, including conservation, coastal protection, carbon sequestration, wood production, or the mixed use of mangroves to produce high sustainable yields14. Despite these efforts, several mangrove rehabilitation projects have struggled to restore ecosystems sustainably in Southeast Asia. This is primarily due to two factors: (1) reliance on monoculture plantations, typically using Rhizophoraceae spp., and (2) inadequate site assessments coupled with insufficient consideration of local ecological principles and environmental conditions15,16. Since 2000, significant mangrove losses due to aquaculture, agriculture, and urban development. However, restoration efforts have gradually reduced the annual loss rate of mangroves from 0.12 to 0.07%17.

The spatial extent of mangrove biomass storage is influenced by mangrove species and their structural diversity4. Species diversity and structural complexity in rehabilitated mangrove forests can vary significantly from those in natural mangrove forests13,18,19,20. The structural complexity of some forest stands may also depend on the local environmental conditions, such as surface elevation, tidal inundation and edaphic parameters4,15,21,22. Furthermore, mangrove ecosystems comprise multiple tree species, with varying stem densities and different growth forms along the sea to land gradient, which makes it challenging to accurately estimate their AGB23,24. Understanding the spatiotemporal patterns (e.g., sea-to-land distribution) of stand structure, species composition, and AGB in natural vs. rehabilitated mangroves is crucial for assessing the carbon sequestration potential and success of ongoing conservation efforts.

Over the last few decades, AGB of mangrove forests has been evaluated under various initiatives including blue carbon projects and the United Nations Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD +) program in the tropics (https://bluecarbonprojects.org/). AGB in mangrove forests can be estimated using two primary methods: field sampling and inventory (destructive and/or non-destructive) and remote sensing-based approaches25,26,27,28,29,30. Field-based forest inventories are labor-intensive and therefore typically involve sampling methods, such as transects, quadrats, or stratified random sampling designs4,23,31. These sampling approaches can account for species distributed from sea to inland areas as well as their structural distributions15,21,32. However, they overlook the impact of environmental and anthropogenic settings, as well as the temporal dynamics of rehabilitated mangroves16.

Field inventory techniques are commonly used to assess the composition, structure, and species diversity of the mangrove ecosystems. Given the resource-intensive nature of destructive sampling, allometric equations are used for estimating the AGB in mangrove forests which facilitate the accurate monitoring of diverse mangrove species and under varying environmental conditions25. Several studies have utilized allometric methods and related parameters to estimate mangrove AGB by correlating it with diameter at breast height (DBH), tree height, tree species density, crown volume, and wood density27,33,34. However, allometric models have limitations owing to the limited number of sampled trees, which may not fully capture forest heterogeneity or adequately address geographical variability35,36. This variability can impede the generalization of estimates across different species, or even the same species in various locations or management practices (e.g., natural versus rehabilitated Rhizophoraceae spp.). Additionally, mangrove ecosystems are affected by natural disturbances such as lightning strikes, storms, and erosion as well as anthropogenic impacts such as deforestation and shrimp farming, which can alter ecosystem dynamics over time. Rehabilitated mangroves often lack the species and structural diversity compared to natural forests, which can affect AGB estimates. This is often due to the monoculture plantation or conservation developing purpose37,32,38. The success of rehabilitation efforts and AGB of such stands are usually assessed by estimating mangrove survival and restored areas, whereas the tree species diversity, structure diversity, and their long-term temporal changes of vegetation, which serve as proxies for functional forests, are rarely considered16,39.

This study addresses these gaps by investigating AGB variations between natural, rehabilitated and regenerated mangrove forests in Trat province, Thailand. It examines species distribution, structural diversity, and their long-term temporal dynamics along sea-to-land gradients to evaluate the carbon sequestration potential of these stands. By integrating 32 years of satellite data with field-based measurements, the study also provides insights into the historical state of natural, rehabilitated and regenerated mangroves. The outcome of this research will contribute to understanding how rehabilitation efforts influence the ecological functions and carbon sequestration capacity of mangrove forests. Such insights are critical for assessing the effectiveness of restoration initiatives and improving conservation practices.

Study area and datasets

Study site

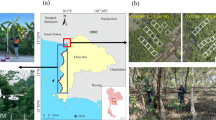

The study site is located in Trat Province, Thailand, along the northeastern coast of the Gulf of Thailand (Fig. 1). Mangrove forests in Trat Province cover approximately 108 km2 and thrive in a tropical monsoon climate, with temperatures ranging from 25 to 30 °C and more than 3000 mm of annual rainfall40,41. The specific inventory site is located between 12° 12′ 7.92′′ N, 102° 36′ 12.71′′ E and 12° 13′ 22.08′′ N, 102° 36′ 54.00′′ E. The surface elevation at the transect site ranges from 0.37 m to 1.1 m above mean sea level. These coordinates represent the starting and ending points of the transect line where comprehensive field data were collected.

Study site location in Trat Province, eastern Thailand, and the sea-to-land distribution of the transect line plots (modified from13). The green, pink and cyan squares indicate the locations of the 10 × 10 m transect plots of natural, rehabilitated and regenerated stands along the transect line. (Map generated using QGIS 3.40.1 (https://qgis.org/).

This research site comprises a vast expanse of mangrove forest located close to the mainland, which has undergone degradation due to shrimp farming and agricultural practices42. The widespread degradation has led to a reduction in natural ecosystem services, such as crab production43. Rehabilitation efforts have been underway in most of these degraded areas since 1994. In this area, rehabilitation projects have implemented monoculture plantations consisting of Rhizophoraceae spp., which are easy to nurse and handle13. This area includes three types of mangrove stands, classified based on their ecological and management characteristics. Natural mangroves are intact forests that have developed without direct human intervention, representing diverse and undisturbed ecosystems. Rehabilitated mangroves are areas restored through human interventions, such as conservation planting projects, and typically involve monoculture plantations. Regenerated mangroves are those that have naturally recolonized previously disturbed sites through ecological succession, without significant human intervention.

The transect location was selected for this study because: (1) it encompasses a large area of rehabilitated mangroves adjacent to a naturally diverse forest (age > 100 years)44, and (2) it includes most of the natural tree species found in eastern Thailand13,23. The study area is home to 13 species of mangroves, including Avicennia alba (Aa), Bruguiera cylindrica (Bc), Bruguiera gymnorhiza (Bg), Bruguiera sexangula (Bs), Ceriops tagal (Ct), Excoecaria agallocha (Ea), Intsia bijuga (Ib), Lumnitzera littorea (Ll), Lumnitzera racemosa (Lr), Rhizophora apiculata (Ra), Rhizophora mucronata (Rm), Xylocarpus granatum (Xg), and Xylocarpus moluccensis (Xm)45.

Landsat imagery and normalized difference infrared index

This study utilized top-of-the-atmosphere data from the Tier 1 collection of Landsat satellite imagery, which were obtained via Google Earth Engine. Specifically, we employed imagery from Landsat TM-5 (1987–2001 and 2003–2011), ETM + (2002–2013), and OLI-8 (2013–2019), covering the period from January 1, 1987, to December 31, 2019. The Tier 1 collection, ideal for time-series analyses, provides Level 1 Precision Terrain processed data, ensuring consistency across different Landsat sensors. We processed the red, green, blue, near-infrared (NIR), shortwave infrared (SWIR)-1, and SWIR-2 bands.

Annual cloud-free composites were generated by removing clouds, cloud shadows, and missing data pixels. This process utilized a filtering algorithm developed previously46, which was later adapted for mangrove forests13,41. The adapted algorithm was based on predefined, knowledge-based rules that reflect the typical spectral signatures of mangroves at certain spatial scales. All Landsat images were normalized using the dark object subtraction (DOS) method47. The DOS process involved applying a linear shift adjustment to each spectral band of the image based on the median value of the mangrove forest13.

In this study, we used the Landsat-based normalized difference infrared index (NDII) to determine the timing and magnitude of disturbances and recovery. The NDII was calculated using Eq. (1):

where NIR is the reflectance in the near-infrared wavelength channel (0.70–0.90 µm), and SWIR is the reflectance in the shortwave-infrared wavelength channel (1.55–1.75 µm;48). The NDII-based time series was used to assess the status of the rehabilitated, regenerated and adjacent natural plots over time (see "Forest stand type, historical state and age of mangrove stands" section).

Field data collection

Mangrove species assemblages typically occupy distinct portions of the intertidal and elevation gradient, ranging from the coastline to the landward side. Studies have highlighted the influence of surface elevation on edaphic parameters associated with species distribution along intertidal zones4,15,16. Based on this, we identified mangrove species and examined variations in their structural features across the sea-to-land gradient using a stratified fixed-area and distance-sampling approach. Forest extent and change information were sourced from Pimple et al.41. Additionally, Sentinel-1 Synthetic Aperture Radar and Sentinel-2 Multispectral Instrument imagery were used to assess the spatial heterogeneity of the different mangrove species23. Plantation area records for Trat Province were obtained from the Office of Mangrove Conservation (Department of Marine and Coastal Resources) and local communities.

A transect spanning 2.67 km was established from the shoreline to the inland forest boundary (Fig. 1). A total of 24 plots, each measuring 10 m × 10 m and separated by 100 m, were established. Of these, 15 were in natural undisturbed stands, 8 were in rehabilitated stands, and 1 was in a regenerated area (Fig. 1). For each plot, tree species names, DBH and tree height were recorded for all trees. Tree heights were measured using a LaserTech TruPulse 200L clinometer. For Rhizophoraceae spp., trunk diameter was measured 30 cm above the highest root27. Field inventory data were collected in December 2018. Dead trees were excluded from measurements, and the next living tree was measured instead.

Methodology

Field data collection

The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normality of structural parameters, including DBH and tree height, and basal area across the different forest plots. As only one data plot was available for the regenerated forest stand, which is insufficient for robust statistical analysis, it was excluded from the analysis, leaving the comparison limited to the natural and rehabilitated forest stands. However, we do report the estimated AGB of this plot. Additionally, the Wilcoxon test was used to compare the DBH, height, and basal area between the natural and rehabilitated stands. Statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.2.2.49

The structural complexity of each plot was quantified using a complexity index, as described previously50,51, and was calculated using Eq. (2):

where, CI is the complexity index, and \(\overline{\mathbf{H} }\) is the mean height.

Species diversity was analyzed using the Shannon or Shannon–Wiener index52, which was calculated using the Vegan package in R53. This commonly used diversity index compares the diversity and variance across different ecological niches, including mangrove ecosystems. It was calculated using Eq. (3):

where H is the Shannon–Weaver diversity index, Pi is the proportion of the individuals of species i to the total number of individuals in the sample, and ln denotes the natural logarithm.

Forest stand type, historical state and age of mangrove stands

The automatic regrowth monitoring algorithm (ARMA), as described by Pimple et al.13, was used in this study to assess the historical status, rehabilitation year, and age of trees within the plots. ARMA uses the Landsat satellite-based NDII to evaluate the timing and magnitude of disturbances, as well as the recovery of the sampled plots. This algorithm enables differentiation between forest rehabilitation and natural regeneration. The ARMA was applied to individual plots to examine historical trends in forest stands, providing valuable insights into the temporal changes and the effectiveness of rehabilitation efforts.

Allometric models for AGB

AGB was estimated by using allometric models and data obtained from sample plots. Owing to the lack of species-specific models for mangrove species found in eastern Thailand and restrictions on destructive sampling imposed by the Thai government, we used a previously developed destructive sampling model from the same study site27 AGB was calculated using Eq. (4):

where \(\normalsize \mathbf{A}\mathbf{G}\mathbf{B}\) (kg/0.01 ha) represents ABG of the plot, \({{\varvec{\rho}}}_{{\varvec{i}}}\)(g/m3) is the species-specific wood density and \({{\varvec{D}}{\varvec{B}}{\varvec{H}}}_{{\varvec{i}}}\) (cm) the diameter at breast height of tree i, and P is the set of trees within the plot. Note: The wood density units in some literatures are presented as ton/m3 or megagram/m3 (Table 1); however, the conversion factor is straightforward. Given that 1 ton/m3 is equivalent to 1,000,000 g/m3 and 1 m3 is 1,000,000 cm3, the conversion from ton/m3 to g/cm3 is direct (e.g., 0.506 ton/m3 = 0.506 g/cm3).

Statistical analyses

In all 23 plots, we analyzed the relationship between AGB and predictor variables including H, CI, and tree density (count). These predictors were used to categorize the stands as natural or rehabilitated mangroves. Equation (5) denotes the model specifications:

where AGB is the square root of AGB; β0 is the intercept; β1, β2, β3, β4, β5, and β6 are the coefficients for each term in the model; H represents the Shannon diversity index; CI represents the complexity index; count represents the tree density; H × type, CI × type, and count × type represent the interaction terms between each predictor and the type variable (i.e., natural and rehabilitated mangrove stands) and ε is the residual error.

To assess whether the categorical variable ‘type’ significantly improved the model, we compared the comprehensive model with a null model that did not include the forest stand type. To evaluate the effects of the predictors on the square root of AGB across the different mangrove stand types, we fitted separate linear models for each type of forest stand. Additionally, to determine the significance of H, CI, tree density (count), and the categorical variable in explaining variance in AGB, we performed analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests on a linear model that included all predictors without interactions. All statistical analyses and visualizations were performed using R (version 4.2.2).

Results

Structural compositions of the mangrove stands

The tree species and structural parameters are presented in Table 2. A total of 13 tree species were recorded across the transect, including the natural (Plots 1–15), rehabilitated (Plots 16–23), and regenerated (Plot 24) mangrove plots (Fig. 1). Significant differences in DBH were observed among species. For instance, the natural species Aa, Bg, Ea, Ll, Ra, Xg, and Xm exhibited larger DBH compared with Ct, Ib, Lr, and the rehabilitated species Rhizophora apiculata (Rar) and Rhizophora mucronata (Rmr).

Significant differences were observed in DBH, basal area, and height across the transect line (Shapiro–Wilk test) (p < 0.05). Additionally, the Whitney U test ( also called Wilcoxon test) revealed that DBH and basal area were significantly higher in the natural stands (Plots 1–15) than in the rehabilitated mangroves (Plots 16–24; Mann–Whitney U test :U = 105 and U = 99, and p < 0.05). However, the height of the rehabilitated mangroves (age > 28 years) did not differ significantly from that of the natural mangroves (Mann–Whitney U test:U = 81 and p > 0.05).

The structural complexity of the forest is shown in Fig. 2. The rehabilitated mangrove stands were structurally less complex than the natural forest stands, as indicated by the CI. Specifically, the CI and mean stand diameter (MSD) ranged from 3.46 to 70.63 and 2.41 to 15.38 cm, respectively, for natural stands, while the corresponding ranges for rehabilitated stands were 6.72–25.17 and 6.57–9.71 cm, respectively. Low CI and MSD values were observed in some natural stands (Plots 9–10, 13, and 15), likely due to the presence of scrub mangroves and the ecotone between the natural and rehabilitated mangroves23. In comparison to the rehabilitated mangrove stands, the naturally regenerated plot (Plot 24) was more diverse and structurally complex (CI = 34.9).

Species and structural diversity of each plot along the transect line. (a) Plots 1–15 are natural stands; (b) Plots 16–23 are rehabilitated stands; (c) Plot 24 is a regenerated stand. The grey color bar indicates the complexity index (CI). The multicolor bar indicates the species according to their basal area; Avicennia alba (Aa), Bruguiera cylindrica (Bc), Bruguiera gymnorhiza (Bg), Bruguiera sexangula (Bs), Ceriops tagal (Ct), Excoecaria agallocha (Ea), Intsia bijuga (Ib), Lumnitzera littorea (Ll), Lumnitzera racemosa (Lr), Rhizophora apiculata (Ra), Rhizophora mucronata (Rm), Xylocarpus granatum (Xg), and Xylocarpus moluccensis (Xm), Rhizophora apiculata rehabilitated (Rar) and Rhizophora mucronata rehabilitated (Rmr).

The ARMA-based analysis (Table 3) revealed that the natural mangrove transect plots (P1–15) exhibited no signs of disturbance during the monitoring period. Conversely, the rehabilitated mangrove stands (P16–23) required a stability period of 7–13 years post-plantation and were aged between 25 and 30 years13. Only one plot of regenerated mangroves (P24) was identified in this study, with a stability period of 13 years and an age exceeding 33 years.

The Shannon diversity index (Table 3) revealed that the natural forest plots exhibited higher diversity, with values ranging from 0.27 to 1.39 (Plots 1–15). In contrast, the rehabilitated stands (Plots 16–23) exhibited lower diversity values, with indices ranging from 0 to 0.48. Zero or very low values in the rehabilitated plots indicated the prevalence of monoculture tree species. The regenerated stands (Plot 24) displayed a diversity index of 1.42, suggesting greater tree species diversity than in the rehabilitated mangrove stands.

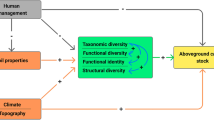

Influence of ecological and structural variables

To understand the factors influencing AGB across different forest stands, we modeled the square root of AGB using three predictors: the H, CI, and tree density (count), incorporating interactions between the predictors and the rehabilitation stand type. The analysis employed a linear regression model, excluding the regenerated plot (Plot 24). The full model, which included all predictors (H, CI, and count), explained a significant proportion of the variance in AGB (Adjusted R-squared = 0.84, p < 0.001). Table 4 presents the coefficients and their significance levels.

H did not significantly affect the forest stand types (p = 0.55), indicating that species diversity does not influence AGB across natural and rehabilitated stands. This lack of significance may be attributed to the presence of scrub mangroves in natural stands and monoculture trees within the rehabilitated mangrove plots, which results in low or negligible species diversity. Hence, the observed variation of these plots compared to that of more diverse natural plots is minimal, which only explains a limited amount of the variance in AGB (Fig. 3 and Table 4).

In contrast, CI had a significant positive effect on AGB in natural mangrove stands (p < 0.001), indicating that higher structural complexity was associated with greater AGB. Tree density, on the other hand, had a significant negative effect on AGB (p < 0.001), suggesting that higher tree density was linked to lower AGB.

AGB was significantly higher in natural mangrove stands than in rehabilitated mangrove stands. Both forest types exhibited a positive relationship between the CI and AGB, with a stronger effect observed in natural forest stands. Tree density had a significantly positive effect on AGB in rehabilitated stands, but a significantly negative effect in natural stands. This suggests that higher tree densities are associated with lower AGB.

The ANOVA results indicated a highly significant effect of mangrove stand type on AGB (p < 0.001). Higher species diversity was associated with variation in biomass, suggesting that highly diverse mangrove forest stands may support higher AGB (p = 0.01). The rehabilitated mangrove stands, which were predominantly monoculture, exhibited different characteristics. CI had a highly significant impact on AGB (p < 0.0001), indicating that a more complex forest structure was associated with higher AGB. Tree density also had a significant effect on AGB (p = 0.003), with higher tree densities correlating with lower AGB.

Mangrove stand AGB

The total AGB, estimated using the model27, ranged from 45.05 to 536.48 tons/ha across the three stands (Fig. 4). Specifically, AGB ranges for natural and rehabilitated stands were 45.05–536.48 tons/ha and 61.57–98.99 tons/ha, respectively, whereas the AGB for the regenerated plot was 14.05 tons/ha. AGB generally increased with stand type, with average values of 236.58 ± 148.66 tons/ha, 78.96 ± 11.83 tons/ha, and 14.05 tons/ha for natural, rehabilitated, and regenerated plots, respectively. Notably, the AGB of natural plots 9 to 13, and 15 was lower than that of other seaward stands, which may be attributed to the presence of scrub mangroves in these natural stands.

Discussion

We assessed the historical development and status of AGB in adjacent natural, rehabilitated, and regenerated mangroves in Trat Province of Thailand, with a focus on estimating AGB and understanding the impact of various variables on its accumulation. Our findings highlight several key aspects of mangrove forest dynamics over a 32-year period, including species diversity, structural complexity, and the overall effects of rehabilitation practices on AGB accumulation.

Our results revealed significant differences in tree species and structural parameters between the natural and rehabilitated mangrove stands, as well as in their temporal dynamics. Natural mangrove stands exhibited larger DBH, greater basal area, and lower tree density than the rehabilitated stands. Tree species diversity and structural complexity in the seaward plots were notably higher than those in the landward plots, including the rehabilitated plots. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies, suggesting that natural forest stands possess greater diversity, complexity, and larger trees18,57,58. CI and MSD revealed that rehabilitated stands were structurally less complex than natural stands, which aligns with the previous observation that rehabilitated stands exhibit thinner canopy layers compared to natural stands23. This structural simplification can be attributed to the fact that rehabilitation efforts are often initiated after severe habitat degradation, such as high-density plantations, water and soil contamination, or hydrological disturbances, such disturbances often occur in areas that have been abandoned by shrimp farms or agricultural activities15,18. The rehabilitation practices in the region, which typically involve planting seedlings at a spacing of ≤ 1.5 × 1.5 m2, may contribute to these structural limitations59. Furthermore, high-density monocultures of Rhizophoraceae spp. often result in reduced structural diversity and growth18. Conversely, the regenerated stands were more diverse and structurally complex than the rehabilitated stands. The presence of larger DBH species such as Bruguiera spp. and Excoecaria agallocha likely contributed to the high CI values.

Our analysis of AGB indicated that natural mangrove stands, even without the influence of specific variables, support greater vegetation biomass than rehabilitated stands. This difference reflects the potentially higher structural and functional capacity of natural mangroves to sustain biomass, which may be attributed to the more mature forest development and ecological stability in these stands60. Different species exhibit unique adaptations and growth patterns that contribute to the higher overall biomass production within natural mangrove ecosystems.

CI had a significant positive effect on AGB in natural stands, highlighting the importance of structural complexity in AGB accumulation. However, the effect of tree species diversity on AGB in natural forests was not significant despite the high species diversity and AGB observed in certain plots (plots 1–8; Fig. 2;4). The natural stands also included scrub mangroves and ecotones between the rehabilitated and adjacent natural stands. Scrub mangroves often exhibit lower structural and species diversity than the more robust natural stands61. These characteristics may influence the diversity index. The disparity in diversity within scrub stands can be attributed to various factors, including environmental conditions and soil stressors such as low nutrient availability and high salinity62,63. In addition, the lack of correlation could be due to low species diversity in rehabilitated stands, where monocultures dominate, thus minimizing the potential impact of diversity on AGB estimates. Interestingly, over the 32 years included in the study, higher tree density was associated with lower AGB in the rehabilitated stands. This could be due to high-density plantations that yield in lower structure development.

The structural complexity and AGB not only support the ecological resilience of mangrove forests but also enhance their capacity to sustain species biodiversity, maximize carbon sequestration potential, and provide a range of essential ecosystem services. Mangrove rehabilitation projects undertaken without careful assessment of site conditions and suitability can negatively impact the overall success, structural complexity, species diversity and AGB production. Our results suggest that while rehabilitation projects can increase mangrove cover and AGB accumulation, achieving species and structural diversity in natural mangrove stands remains a considerable challenge. These findings are consistent with those of studies that have reported lower levels of structural diversity and AGB accumulation18,58,64. Furthermore, rehabilitated mangroves provide lower-level biogeochemical functions and ecosystem services58. Interestingly, the regenerated stands located on the landward side exhibit slightly higher structural complexity and AGB than other stands. This observed difference is likely attributed to the role of propagule dispersal facilitated by artificial drainage canals that are connected to natural canals23. These canals provide a conduit for the transport of propagules from adjacent natural stands during high tides, enabling the natural regeneration of mangrove species in the regenerated areas65,66. Planting combination of different mangrove species at low densities is preferable to facilitate the natural recruitment of other species67.

Variations in AGB storage are influenced by geophysical factors (elevation, tidal inundation), climate, and edaphic properties, which collectively shape species diversity, structure, and function along the sea-to-land gradient32,68. While most AGB estimates focus on well-developed forests, scrub forests are often overlooked69. Additionally, in mangrove ecosystems, diversity can occur in single species, groups, or randomly, which contrasts with the uniformity of monoculture plantations. Projects for rehabilitating mangrove forests are considered a strategic approach to mitigating carbon emissions considering the high carbon sequestration potential (“blue carbon”) of mangrove ecosystems70. The integration of blue carbon mitigation at the national level is aligned with the Paris Agreement and associated nationally determined contributions of countries like Thailand71. However, persistent limitations in the available data at both national and international levels contribute to considerable variability in AGB estimates and the measured success of rehabilitation projects. Our results revealed AGB and structural diversity along the sea-to-land gradient. The AGB in natural scrub mangroves is comparable to that of 28-year-old rehabilitated stands but is lower than that in other adjacent natural stands. This finding underscores the importance of environmental and anthropogenic factors in influencing AGB and structural complexity. Understanding the temporal dynamics of rehabilitated stands allowed us to assess the success of rehabilitated mangroves over a 28-year period in terms of species composition, structural complexity, and AGB storage capacity. The inclusion of temporal dynamics provided a comprehensive perspective on secondary succession, indicating the absence of significant disturbances in natural, rehabilitated, and regenerated stands over the study period. Blue carbon projects and initiatives are often hindered by the lack of baseline data25. The proposed approach addresses this gap, potentially reducing uncertainties in blue carbon estimations at the ecosystem level and supporting national mitigation goals.

Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive assessment of the dynamics, structural complexity, and AGB of mangrove forests in Thailand, emphasizing the differences between natural, rehabilitated, and regenerated stands. Our findings revealed that natural mangrove forests exhibit higher AGB, and structural complexity compared to rehabilitated and regenerated stands. The Shannon diversity index did not significantly influence AGB in either forest type, which may be explained by the relatively lower diversity observed in rehabilitated mangroves. In natural mangrove stands, structural complexity positively influenced AGB, underscoring the critical role of maintaining structural diversity. Conversely, rehabilitated areas with higher tree densities were associated with reduced AGB over a 32-year period, suggesting that overly dense plantations may inhibit optimal biomass accumulation.

These findings underscore the importance of balancing tree density, ecological complexity, and species diversity to enhance carbon sequestration and support ecosystem health in mangrove restoration efforts. They also highlight the value of combining transect-based field surveys, which capture species and environmental variability across sea-to-land gradients, with remote sensing-based time-series analyses, which provide insights into historical dynamics and long-term changes in natural, rehabilitated and regenerated stands. This integrative approach improves our ability to evaluate the spatiotemporal scale of rehabilitation projects and their success in fostering carbon sequestration and ecosystem function.

Future mangrove rehabilitation efforts should prioritize strategies that enhance both species and structural diversity to improve ecosystem effectiveness and resilience. Our study demonstrates that similar methodologies can be applied to assess the outcomes of large-scale mangrove rehabilitation projects and to monitor their contributions to carbon storage and other ecosystem services over time.

Data availability

The data collection of this research was funded by the Southeast Asia-Europe Joint Funding Scheme for Research and Innovation (SEA-EU-NET), 2018–2022 as a part of a project entitled, “Monitoring and optimizing the design quality of mangrove restoration towards a sustainable coastal ecosystem management in Thailand and Mekong Delta of Vietnam” [Project code:- Thailand (NSTDA): P-18–51184, France (ANR): N0 ANR- 17-ASIE-0003-01, Germany (BMBF): 01DQ18004]. Data is provided within the manuscript https://www.data-in-brief.com/article/S2352-3409(20)30394-2/pdf.

References

Alongi, D. M. Carbon sequestration in mangrove forests. Carbon Manag. 3, 313–322. https://doi.org/10.4155/cmt.12.20 (2012).

Donato, D. C. et al. Mangroves among the most carbon-rich forests in the tropics. Nat. Geosci. 4, 293–297. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1123 (2011).

Elwin, A., Bukoski, J. J., Jintana, V., Robinson, E. J. Z. & Clark, J. M. Preservation and recovery of mangrove ecosystem carbon stocks in abandoned shrimp ponds. Sci. Rep. 9, 18275. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54893-6 (2019).

Bai, J. et al. Mangrove diversity enhances plant biomass production and carbon storage in Hainan island, China. Funct. Ecol. 35, 774–786. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.13753 (2021).

Huxham, M. et al. Mangroves and people: Local ecosystem services in a changing climate. In Mangrove Ecosystems: A Global Biogeographic Perspective (eds Rivera-Monroy, V. H. et al.) 245–274 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-62206-4_8.

Duke, N. C. et al. A world without mangroves?. Science 317, 41–42. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.317.5834.41b (2007).

Polidoro, B. A. et al. The loss of species: Mangrove extinction risk and geographic areas of global concern. PLoS One 5, e10095. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0010095 (2010).

Alongi, D. M. The impact of climate change on mangrove forests. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 1, 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-015-0002-x (2015).

Alongi, D. M. Mangrove forests: Resilience, protection from tsunamis, and responses to global climate change. Estuarine Coast Shelf Sci. 76, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2007.08.024 (2008).

Richards, D. R. & Friess, D. A. Rates and drivers of mangrove deforestation in Southeast Asia, 2000–2012. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 344–349. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1510272113 (2016).

Alexandris, N., Chatenoux, B., Lopez Torres, L., Peduzzi, P. Monitoring mangroves restoration from space. (UNEP/GRID- Geneva, 2013).

Gerona-Daga, M. E. B. & Salmo, S. G. A systematic review of mangrove restoration studies in Southeast Asia: Challenges and opportunities for the United Nation’s decade on ecosystem restoration. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 987737. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.987737 (2022).

Pimple, U. et al. A history of the rehabilitation of mangroves and an assessment of their diversity and structure using Landsat annual composites (1987–2019) and transect plot inventories. For. Ecol. Manag. 462, 118007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118007 (2020).

Andradi-Brown, D. A., Howe, C., Mace, G. M. & Knight, A. T. Do mangrove forest restoration or rehabilitation activities return biodiversity to pre-impact levels?. Environ. Evid. 2, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/2047-2382-2-20 (2013).

Ellison, A. M. Mangrove restoration: Do we know enough?. Restor. Ecol. 8, 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1526-100X.2000.80033.x (2000).

Pimple, U. et al. Enhancing monitoring of mangrove spatiotemporal tree diversity and distribution patterns. Land Degrad. Dev. 34, 1265–1282. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.4537 (2022).

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The world’s mangroves 2000–2020. (FAO, Rome, 2023). https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/7f15adf1-2756-4e86-a6dd-77d0fc26d97c/content.

Asaeda, T. et al. Mangrove plantation over a limestone reef—good for the ecology? Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 173, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2016.02.017 (2016).

Azman, M. S. et al. Stand structure, biomass and dynamics of naturally regenerated and restored mangroves in Malaysia. For. Ecol. Manag. 482, 118852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118852 (2021).

Ren, H. et al. Restoration of mangrove plantations and colonisation by native species in Leizhou bay, South China. Ecol. Res. 23, 401–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11284-007-0393-9 (2008).

Krauss, K. W. & Osland, M. J. Tropical cyclones and the organization of mangrove forests: A review. Ann. Bot. 125, 213–234. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcz161 (2019).

Ma, W., Wang, W., Tang, C., Chen, G. & Wang, M. Zonation of mangrove flora and fauna in a subtropical estuarine wetland based on surface elevation. Ecol. Evol. 10, 7404–7418. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.6467 (2020).

Pimple, U. et al. Assessing mangrove species diversity, zonation and functional indicators in response to natural, regenerated, and rehabilitated succession. J. Environ. Manag. 318, 115507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115507 (2022).

Soares, M. L. G. & Schaeffer-Novelli, Y. Above-ground biomass of mangrove species. I. Analysis of models. Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 65, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2005.05.001 (2005).

Farzanmanesh, R., Khoshelham, K. & Thomas, S. Technological opportunities for measuring and monitoring blue carbon initiatives in mangrove ecosystems. Remote Sens. Appl. 24, 100612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsase.2021.100612 (2021).

Kauffman, J. B. et al. Total ecosystem carbon stocks of mangroves across broad global environmental and physical gradients. Ecol. Monogr. 90, e01405. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecm.1405 (2020).

Komiyama, A., Poungparn, S. & Kato, S. Common allometric equations for estimating the tree weight of mangroves. J. Trop. Ecol. 21, 471–477. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266467405002476 (2005).

Lucas, R. et al. Spatial ecology of mangrove forests: A remote sensing perspective. In Mangrove Ecosystems: A Global Biogeographic Perspective (eds Rivera-Monroy, Victor H. et al.) 87–112 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-62206-4_4.

Pham, T. D., Yokoya, N., Bui, D. T., Yoshino, K. & Friess, D. A. Remote sensing approaches for monitoring mangrove species, structure, and biomass: Opportunities and challenges. Remote Sens. (Basel) 11, 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11030230 (2019).

Wang, L., Jia, M., Yin, D. & Tian, J. A review of remote sensing for mangrove forests: 1956–2018. Remote Sens. Environ. 231, 111223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2019.111223 (2019).

Huang, Z. et al. Estimating mangrove above-ground biomass at Maowei Sea, Beibu Gulf of China using machine learning algorithm with Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data. Geocarto Int. 37, 15778–15805. https://doi.org/10.1080/10106049.2022.2102226 (2022).

Ellison, A. M., Mukherjee, B. B. & Karim, A. Testing patterns of zonation in mangroves: Scale dependence and environmental correlates in the Sundarbans of Bangladesh. J. Ecol. 88, 813–824. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2745.2000.00500.x (2000).

Chave, J. et al. Tree allometry and improved estimation of carbon stocks and balance in tropical forests. Oecologia 145, 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-005-0100-x (2005).

Komiyama, A., Ong, J. E. & Poungparn, S. Allometry, biomass, and productivity of mangrove forests: A review. Aquat. Bot. 89, 128–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquabot.2007.12.006 (2008).

Cairns, M. A., Olmsted, I., Granados, J. & Argaez, J. Composition and aboveground tree biomass of a dry semi-evergreen forest on Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. For. Ecol. Manag. 186, 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1127(03)00229-9 (2003).

Weiskittel, A. R. et al. A call to improve methods for estimating tree biomass for regional and national assessments. J. For. 113, 414–424. https://doi.org/10.5849/jof.14-091 (2015).

Field, C. D. Mangrove rehabilitation: Choice and necessity. Hydrobiologia 413, 47–52. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1003863415354 (1999).

Naohiro, M., Putth, S. & Keiyo, M. Mangrove rehabilitation on highly eroded coastal shorelines at Samut Sakhon, Thailand. Int. J. Ecol. 2012, 171876 (2012).

Djamaluddin, R. et al. Point of (no) return? Vegetation structure and diversity of restored mangroves in Sulawesi, Indonesia, 14–16 years on. Restor. Ecol. 31, e13963. https://doi.org/10.1111/rec.13963 (2023).

Chalermchatwilai, B., Poungparn, S. & Patanaponpaiboon, P. Distribution of fine-root necromass in a secondary mangrove forest in Trat Province, eastern Thailand. ScienceAsia 37, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.2306/scienceasia1513-1874.2011.37.001 (2011).

Pimple, U. et al. Google Earth Engine based three decadal Landsat imagery analysis for mapping of mangrove forests and its surroundings in the Trat Province of Thailand. J. Comput. Commun. 6, 247–264. https://doi.org/10.4236/jcc.2018.61025 (2018).

Department of Marine and Coastal Resources (DMCR). 2014. Mangrove forest conservation in Thailand: A review of progress and challenges. (in Thai).

Department of Marine and Coastal Resources (DMCR). 2019. The State of Marine and Coastal Resources and Coastal Erosion. Bangkok, Thailand: Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment; 2019. (in Thai).

Department of Marine and Coastal Resources (DMCR). 2018. Status of mangrove resources in Trat Province. (in Thai).

Pimple, U. Dataset on plot inventories of species diversity and structural parameters of natural and rehabilitated mangrove forest in the Trat Province of Thailand. Data Brief 30, 105500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2020.105500 (2020).

Simonetti, D., Simonetti, E., Szantoi, Z., Lupi, A. & Eva, H. D. First results from the phenology-based synthesis classifier using Landsat 8 imagery. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 12, 1496–1500. https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2015.2409982 (2015).

Bodart, C. et al. Pre-processing of a sample of multi-scene and multi-date Landsat imagery used to monitor forest cover changes over the tropics. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 66, 555–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2011.03.003 (2011).

Jackson, T. J. et al. Vegetation water content mapping using Landsat data derived normalized difference water index for corn and soybeans. Remote Sens. Environ. 92, 475–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2003.10.021 (2004).

R Core Team. (2023). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from https://www.R-project.org/

Araújo, R. J. & Shideler, G. S. An R package for computation of mangrove forest structural parameters using plot and plotless methods. Madera Bosques https://doi.org/10.21829/myb.2019.2511696 (2019).

Holdridge, L.R. Life zone ecology. (Tropical Science Center, San Jose, Costa Rica, 1967).

Spellerberg, I. F. & Fedor, P. J. A tribute to Claude Shannon (1916–2001) and a plea for more rigorous use of species richness, species diversity and the “Shannon-Wiener” Index. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 12, 177–179. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1466-822X.2003.00015.x (2003).

Oksanen, J., Blanchet, F. G., Friendly, M., Kindt, R., Legendre, P., McGlinn, D., Minchin, P. R., O’Hara, R. B., Simpson, G. L., Solymos, P., Stevens, M. H. H., Szoecs, E., & Wagner, H. vegan: Community Ecology Package (Version 2.6-4). Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (2023).

Saenger, P. Mangrove ecology, silviculture, and conservation (Springer, Dordrecht, 2002).

Jachowski, N. R. A. et al. Mangrove biomass estimation in Southwest Thailand using machine learning. Appl. Geogr. 45, 311–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2013.09.024 (2013).

Sosef, M. S. M. 1993. Intsia bijuga (Colebr.) O. Kuntze. In Plant Resources of South-East Asia No. 5(1): Timber trees; Major commercial timbers (eds Soerianegara, I., & Lemmens, R. H. M. J.) xx–xx. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Retrieved from https://prosea.prota4u.org/

Cameron, C., Hutley, L. B., Friess, D. A. & Brown, B. Community structure dynamics and carbon stock change of rehabilitated mangrove forests in Sulawesi. Indonesia. Ecol. Appl. 29, e01810. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.1810 (2019).

Su, J., Friess, D. A. & Gasparatos, A. A meta-analysis of the ecological and economic outcomes of mangrove restoration. Nat. Commun. 12, 5050. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-25349-1 (2021).

Macintosh, D. J. & Ashton, E. C. A review of mangrove biodiversity conservation and management, Centre for Tropical Ecosystems Research (University of Aarhus, Denmark, 2002).

Bosire, J. O. et al. Functionality of restored mangroves: A review. Aquat. Bot. 89, 251–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquabot.2008.03.010 (2008).

Estrada, G. C. D., Soares, M. L. G., Chaves, F. O. & Cavalcanti, V. F. Analysis of the structural variability of mangrove forests through the physiographic types approach. Aquat. Bot. 111, 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquabot.2013.06.003 (2013).

Aljahdali, M. O., Alhassan, A. B. & Zhang, Z. Environmental factors causing stress in Avicennia marina mangrove in Rabigh lagoon along the Red Sea: Based on a multi-approach study. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 646993. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.646993 (2021).

Feller, I. C. Effects of nutrient enrichment on growth and herbivory of dwarf red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle). Ecol. Monogr. 65, 477–505. https://doi.org/10.2307/2963499 (1995).

Barnuevo, A., Asaeda, T., Sanjaya, K., Kanesaka, Y. & Fortes, M. Drawbacks of mangrove rehabilitation schemes: Lessons learned from the large-scale mangrove plantations. Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 198, 432–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2017.02.015 (2017).

Di Nitto, D. et al. Mangroves facing climate change: Landward migration potential in response to projected scenarios of sea level rise. Biogeosciences 11, 857–871. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-11-857-2014 (2014).

Triest, L. et al. Channel network structure determines genetic connectivity of landward–seaward Avicennia marina populations in a tropical bay. Ecol. Evol. 10, 12059–12075. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.6829 (2020).

Macintosh, D. J. & Ashton, E. C. Growth and carbon stocks in four mangrove species planted on a former charcoal concession site in Ranong, Thailand. Carbon Footprints 2, 14. https://doi.org/10.20517/cf.2023.26 (2023).

Twilley, R. R., Castañeda-Moya, E., Rivera-Monroy, V. H. & Rovai, A. Productivity and carbon dynamics in mangrove wetlands. In Mangrove Ecosystems: A Global Biogeographic Perspective (eds Rivera-Monroy, V. H. et al.) 113–162 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-62206-4_5.

Virgulino-Júnior, P. C. C., Carneiro, D. N., Nascimento, W. R., Cougo, M. F. & Fernandes, M. E. B. Biomass and carbon estimation for scrub mangrove forests and examination of their allometric associated uncertainties. PLoS One 15, e0230008. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230008 (2020).

López-Portillo, J. et al. Mangrove forest restoration and rehabilitation. In Mangrove Ecosystems: A Global Biogeographic Perspective: Structure, Function, and Services (eds Rivera-Monroy, V. H. et al.) 301–345 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-62206-4_10.

Taillardat, P., Friess, D. A. & Lupascu, M. Mangrove blue carbon strategies for climate change mitigation are most effective at the national scale. Biol. Lett. 14, 20180251. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2018.0251 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the Department of Marine and Coastal Resources Trat office staff Mr. Tamanai Pravinvongvuthi, Mr. Anuchit Jaikuea, Mr. Ruchakorn Tanasomboonpan, and Mr. Thanakrit Bunkoed—for their unwavering support and active participation during the all-species diversity field surveys of the project. Additionally, we would like to thank Mr. Kumron Leadprathomc of the Royal Forest Department for his support and participation during these critical surveys. We extend our thanks to Dr. Robert Schlicht from Technische Universität Dresden for his invaluable statistical advice.

Funding

This research was supported by Srinakharinwirot university, Thailand as a part of a project entitled, “Above ground biomass estimation for different species of plantation mangrove using Remote Sensing and Machine Learning”. Grant number: SWU 610/2564. This research was carried out under the MOPGA 2022 visiting fellowship program for young researcher candidate for the project entitled “Mangrove Forest Carbon Sequestration Potential to enhance the national climate change mitigation strategies in Thailand” (Reference: mopga-postdoc-2022—0475689180). The data collection of this research was funded by the Southeast Asia-Europe Joint Funding Scheme for Research and Innovation (SEA-EU-NET), 2018–2022 as a part of a project entitled, “Monitoring and optimizing the design quality of mangrove restoration towards a sustainable coastal ecosystem management in Thailand and Mekong Delta of Vietnam” [Project code:- Thailand (NSTDA): P-18-51184, France (ANR): N0 ANR- 17-ASIE-0003-01, Germany (BMBF): 01DQ18004].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.S.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Original draft preparations, Project administration. U.P.: Methodology, Data collection, Fromal, Analysis, planning and Investigation, Project administration. V.G.: Data collection, Commentary, Project administration. C.P.: Methodology, Commentary.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sitthi, A., Pimple, U., Piponiot, C. et al. Assessing the effectiveness of mangrove rehabilitation using above-ground biomass and structural diversity. Sci Rep 15, 7839 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92514-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92514-7