Abstract

Tongue squamous cell carcinoma (TSCC) remains an unsolved medical problem due to its poor local recurrence rate and prognosis. The purpose of this study was to investigate the expression characteristics of RAC-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1(RAC1) in TSCCS and its role in tumor invasion and metastasis. In this study, immunohistochemical staining was used to detect RAC1 expression in 150 tongue cancer specimens. The correlation between RAC1 and clinical-pathological characteristics is analyzed, along with the association between protein levels and disease-specific survival, metastasis-free survival, and local recurrence-free survival. In vitro experiments, RAC1 was knocked down by short hairpin RNA transfection to reveal the role of RAC1 in the invasion and metastasis of TSCC. The regulatory effects of RAC1 on CAL27 cell migration and invasion were evaluated by scratch and invasion methods. The influence of RAC1 expression on tumor growth was scrutinized using a subcutaneous transplant model in nude mice. RAC1 is overexpressed in TSCC and positively correlates with tumor invasion and metastasis. Moreover, elevated RAC1 expression is associated with poorer differentiation. Survival analysis further indicates that high expression of RAC1 is linked to increased recurrence and metastasis rates, as well as poorer prognosis. Additionally, both in vivo and in vitro studies demonstrate that RAC1 may impact tumor progression by modulating the epithelial–mesenchymal transition process through the RAC1/PAK1/LIMK1 signaling pathways. RAC1 overexpression is closely related to the progression of TSCC, and may provide a new prognostic indicator and therapeutic target for tongue cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tongue squamous cell carcinoma (TSCC) is one of the most common head and neck malignancies, with more than 830,000 new cases and approximately 430,000 deaths each year1. As the site of tongue squamous cell carcinoma is located at the beginning of respiratory tract and digestive tract, the growth and invasion of tumor cause great damage to patients’ breathing, swallowing, chewing, vocalization and other basic physiological functions, and greatly threaten the life of patients2. Most patients with tongue squamous cell carcinoma are in an advanced stage at the time of diagnosis and usually require a combination of sequential treatments including surgery, radiation, chemotherapy and immunotherapy. In recent years, targeted therapy based on drugs targeting specific molecular targets has received widespread attention, and novel targeted therapy strategies are developing rapidly to treat and improve patient survival. Therefore, the search for new therapeutic targets and prognosis guidance has become a hot topic at home and abroad.

Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1(RAC1) is a small guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) protein from the Rho family, which participates in regulating cytoskeletal dynamics3. Several studies have reported that RAC1 is overexpressed in a variety of carcinomas, such as lung cancers, bladder/urinary tract cancers and melanoma4,5,6. Lin et al. found that high RAC1 expression was negatively correlated with survival in HER2-enriched basal breast invasive carcinoma7. RAC1 has been suggested to affect the migration and invasion of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) through the EGFR/Vav2/RAC1 axis8. Manabu Yamazaki et al. also demonstrated that oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) relies on RAC1 to phagocytose apoptotic cancer cells and promote tumor cell metastasis9. However, most studies remain at the level of basic research and lack clinical data, especially for TSCC patients in China. In addition, studies have also confirmed that a variety of inhibitors including EHT 1864, ZINC 69391, NSC 23766 and its derivatives can inhibit the activity of RAC1 by interfering with the binding of RAC1 and GEFs10,11,12, so as to effectively block the invasion and metastasis of various cancer cells. The above evidence suggested that RAC1 can be considered as a potential target for TSCC therapy.

The purpose of this study was to clarify the possibility of RAC1 as a potential therapeutic target for primary TSCC. This study includes two contents: First, the mechanism of RAC1 in invasion and metastasis of TSCC. Second, the correlation between RAC1 and prognosis of TSCC.

Materials and methods

Patient population and clinical samples

The sample of this study was collected from 150 patients who received radical surgery for tongue squamous cell carcinoma in the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University from 2013 to 2023. All primary lesions were histologically confirmed as tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Exclusion criteria were :(1) patients with distant metastasis; (2) Patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy. Clinical parameters of patients with TSCC were extracted and included age, sex, smoking history, TNM stage, histological differentiation and survival data (Table 1). Data from the study were updated through July 30, 2023 through follow-up visits and telephone calls. Median follow-up time was 56 months (range 2–129). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University (QYFYWZLL 28181). All research was conducted in accordance with the guidelines established by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University. Informed consent was obtained from all patients included in the study. Research involving human participants was carried out in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Histopathological examination

Human tongue cancer tissue sections were deparaffinized using xylene and subsequently rehydrated with ethanol. The sections were incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 10 min. Heat-induced antigen retrieval was performed in 0.01 M sodium citrate buffer (pH 6) at 94 °C for 30 min. The sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with a rabbit anti-human RAC1 antibody (1:400; Abcam, USA). Subsequently, they were incubated at room temperature for 30 min with an HRP-labeled secondary antibody (1:400). Prepared DAB chromogenic solution was applied to the surface, and imaging was performed using the NovoLink polymer detection system (Leica Microsystems, Germany). Finally, the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin for 30 s. The results of the immunohistochemistry were evaluated based on the percentage of positively stained cells and the intensity of the staining.

Cell culture

The TSCC cell line CAL27, obtained from Advanced Research Center of Central South University (HuNan, China), was cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute # 1640 (RPMI) medium (Hyclone, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO, USA), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 U/ml streptomycin (GIBCO, USA). All cells were cultured in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in an incubator at 37℃.

ShRAC1 synthesis and transfection

RAC1-specific shRNA sequences were designed based on the RAC1 gene template. The sequences for the shRNAs were as follows: shRNA 1: 5′-GGAACAGCTCATCCTTATG-3′; shRNA 2: 5′-CGACTTAAGCCGAGTAAAT-3′; shRNA 3: 5′-GACTTCTGAACGCCTTCTA-3′. Control groups were transfected with either a transfection reagent (blank control, BC). CAL27 cells (5 × 10⁶) were seeded in 6-well plates with 2 mL of medium without antibiotics (streptomycin). Upon reaching approximately 50% confluency, the cells were transfected with 2 μg of recombinant plasmid using P3000 Reagent and Lipofectamine™ 3000, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The plasmid vectors used in this experiment were based on the pLenti6.3/V5-DEST lentiviral backbone (Genechem, China). Lentiviral plasmids expressing the RAC1 shRNAs and NC were packaged in 293 T cells using Lipofectamine™ 3000 reagent (Invitrogen, USA), along with helper plasmids for viral production. The virus-containing supernatant was collected 48 h post-transfection, concentrated, and used to infect CAL27 cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 30, in the presence of 5 μg/mL polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). The negative control group consisted of CAL27 cells transfected with an empty vector lentivirus. After 48 h of infection, stable knockdown was confirmed by PCR and Western blot analysis.

Cell migration and invasion analysis

Cell migration was assessed using a wound-healing motility assay. Transfected cell lines were seeded into 24-well plates and grown to confluence. After creating an artificial wound with a pipette tip, the cells were rinsed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Images were immediately captured (time 0 h), and the remaining cells were incubated for 48 h in RPMI medium with 1% FBS. Closure of the scratched areas was evaluated using bright-field microscopy at 48 h. Cell invasion assays were conducted using Transwell chambers (Corning, USA). Transfected cells were serum-starved for 24 h and seeded into the upper chamber with serum-free media, while medium containing 20% FBS was added to the lower chamber. After 24 h of incubation, the migrated cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with 0.1% crystal violet solution. Five random fields from the lower side of the filter membrane, where migrated cells were located, were selected under the microscope, and images were captured for cell counting.

Western blot analysis

Cells were harvested after treatment for 48 h. After treatment, the cells were harvested and homogenized in lysis buffer (Sigma, USA). Protein concentrations were measured using a commercially available BCA Protein Assay Kit (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA). After quantification, protein samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane, which was then incubated with specific antibodies (Affinity Biosciences, China): RAC1 (1:800), PAK1(1:1000), LIMK1(1:1000), Phospho-PAK1 (1:1000), Phospho-LIMK1 (1:1000), GAPDH (1:5000). The secondary antibody (1:5000) was added and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Following this, the BeyoECL Plus kit (Beyotime, China) was applied, and Signals from immunoreactive bands were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham, United Kingdom). Immunoblot signals were quantified using FIJI (Fiji Is Just ImageJ) software (http://imagej.net/Fiji).

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the cells in each group 48 h after transfection using a RNAprep pure Tissue Kit (TIANGEN, China), and was reverse transcribed to complementary DNA using a Fast Quant RT Kit (TIANGEN, China). Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was performed in a 20 μL reaction system, where cDNA was mixed with forward and reverse primers and SuperRealPreMix Plus (RiboBio, China), then subjected to detection. GAPDH (Shanghai Sangon Biological Engineering Technology & Services Co., Ltd, China) was used as an internal standard gene. Primers were synthesized by Takara Bio., Inc (Shiga, Japan). The levels of RAC1 and control GAPDH mRNA transcripts were determined using reverse transcriptase-PCR using a thermal cycler (Stratagene, USA). Each PCR was performed in duplicate with initial denaturation at 95℃ for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95℃ for 5 s, annealing, and extension at 60℃ for 31 s. The cycle threshold (CT) for each reaction was recorded. The following primer sets were used: RAC1, forward (F), 5′-CTCCTGCTGATTTCACTTTGG-3′, reverse (R), 5′-CCACGACAAAGTTGTGGTTCA-3′. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Animal model

20 male BALB/c nude mice (5 weeks old) were purchased from the Pengyue Company (Jinan, China). The animal experiments protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University and all experiments in this study were performed in accordance with the animal experiment guide established by the affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University. All animal experiments complied with the ARRIVE guidelines. RAC1-silcencing CAL27 cells were subcutaneously injected into the upper right flank of nude mice to establish the tumor xenograft model. The size of the subcutaneous ectopic neoplasms was monitored every 7 days. After 35 days, the tumor size exceeded 650 mm3, mice euthanasia was performed by isoflurane overdose. and the tumors were surgically excised. The tumor volumes were calculated using the formula V = (W × L × H)/2, and the weights of the excised tumors were recorded.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Corporation, USA). Results are expressed as mean ± SD, and statistical significance was determined using analysis of variance analysis and the Student–Newman–Keuls q test (SNK-q test); Kaplan–Meier method and the Multivariate analyses were conducted to identify significant independent factors for the prognosis. differences with P < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

RAC1 was highly expressed in TSCC tissues

RAC1 expression in tumor and paracancer tissues was compared by immunohistochemistry (IHC). RAC1 was expressed in both nucleus and cytoplasm. RAC1 expression in TSCC was significantly higher than that in normal tissues and adjacent to cancer. Statistical analysis indicated a correlation between RAC1 expression and the histological grade of TSCC, with RAC1 showing a positive correlation with TSCC histological differentiation (Fig. 1). In addition, we found a similar trend in RAC1 mRNA expression in TSCCS with different degrees of differentiation (Fig. 1).

RAC1 was positively correlated with TSCC metastasis

Migration and invasion experiments revealed that CAL27 cells with higher RAC1 levels exhibited stronger aggressive growth abilities. Transfection of CAL27 cells with shRAC1 resulted in a significant reduction in the migration and invasion abilities in the experimental group compared to the control group (Figs. 2, 3).

Effect of RAC1 knockdown on CAL27 cells wound healing ability. The wound areas were generated by scratching with 10 μl pipette tips. The wound healing of CAL27 cells was observed and photographed at 0 h and 48 h using an optical microscope. BC blank control group, NC negative control group. ***p < 0.001.

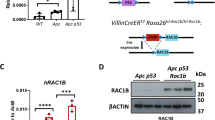

RAC1 silencing inhibits the activation of PAK1/LIMK1 signaling pathway

The activation of PAK1/LIMK1 signaling following RAC1 silencing was investigated in our study. Following the knockdown of RAC1, mRNA expression exhibited a significant decrease. Subsequent analysis of protein changes revealed a significant reduction in the protein levels of RAC1, PAK1, and LIMK1, concomitant with a notable reduction in the phosphorylation levels of PAK1 and LIMK1 (Fig. 4). These findings indicate that silencing RAC1 may impede the activation of PAK1/LIMK1 signaling (Fig. 5).

Effect of RAC1 knockdown on epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) proteins in CAL27 cells. (a) Immunoblotting analysis was conducted for PAK1 and LIMK1 proteins in CAL27 cells transfected with either control or shRAC1. The quantification of immunoblotting results for the specified proteins was performed using ImageJ and normalized against GAPDH. (b) The mRNA expression of RAC1 in CAL27 cells transfected with RAC1 shRNA. BC blank control group, NC negative control group. ****p < 0.0001.

Disease-specific survival probabilities (DSS), local relapse-free survival probabilities (LRFS), and metastasis-free survival probabilities (MFS) for TSCC patients based on RAC1 protein expression. (a) High RAC1 expression group had a shorter DSS. (b) High RAC1 expression group had a shorter LRFS. (c) High RAC1 expression group had a shorter MFS. ***p < 0.001.

RAC1-silenced CAL27 cells showed a slower growth and less invasion in the mouse model of TSCC

We investigated the impact of RAC1 on in vivo tumor growth by utilizing CAL27 cells transfected with shRAC1. These transfected cells were subcutaneously inoculated into nude mice, and the progression of tumor growth was monitored on a weekly basis. Following a 5-week duration, the tumors were harvested, and the mice were sacrificed. Tumors in the shRAC1 group showed a slower growth, with smaller tumor volumes and lower tumor weights (Fig. 6).

Silencing of RAC1 inhibits tumor growth in vivo. (a, b) Mice in each group were inoculated with shRAC1-transfected cells or negative control cells, respectively. After 35 days of inoculation, the mice were euthanized, and tumors were obtained. (c) The volumes of tumor bodies were measured weekly. (d) The changes in tumor weight in each group. (e) IHC assays showed the expression of RAC1, PAK1and LIMK1 in tumor tissues from the indicated groups. BC blank control group, NC negative control group. ***p < 0.001.

RAC1 overexpression was negatively associated with prognosis

According to Kaplan–Meier analysis, the TSCC patients were divided into high-RAC1 expression group (n = 84) and low-RAC1 expression group (n = 66). The disease-specific survival (DSS) of patients with high RAC1 expression was significantly shorter than those with low RAC1 expression (P = 0.0004). Similarly, local relapse-free survival (LRFS) and metastasis-free survival (MFS) were significantly shorter in patients with high RAC1 expression than in patients with low RAC1 expression. Therefore, high RAC1 expression in TSCC is significantly associated with reduced postoperative specific survival of patients (Fig. 5).

RAC1 can be used as a significant predictor of survival in patients with TSCC

Univariate survival analysis showed that RAC1 was a potential predictor of DSS, MFS, and LRFS in patients with TSCC (Tables 2, 3, 4). By multivariate comparison, we further determined that RAC1 was a significant prognostic factor for DSS (P = 0.015) and LRFS (P = 0.021), but not MFS (Table 4).

Discussion

High RAC1 expression is closely associated with malignant biological behavior of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). However, the data available is draw mainly from Caucasian studies, while data from studies of Asian populations are limited. Only 11 RAC1-positive HNCSS samples from Asians were found through the TCGA database search. Studies on RAC1 expression in Chinese patients are even rarer. Based on this, we conducted a retrospective single-center study of 150 patients with surgically resected TSCCs. Studies have confirmed that RAC1 plays an important role in the progression of TSCC, and its overexpression is significantly associated with poor prognosis of the disease.

RAC1 overexpression can promote the progression of tumor development in many organs, including breast, lung, colorectal, and prostate13,14. Several studies have shown that RAC1 overexpression levels are associated with progression, metastasis, and radiotherapy resistance in non-small cell lung cancer5,15. M. Liu et al. reported that RAC1 played an important role in cell adhesion and migration in HNSCCs16, which may promote tumor progression. Compared with other malignant tumors, TSCCs have the characteristics of vigorous early proliferation, high incidence of local invasion and recurrence, and high incidence of lymph node metastasis. This study revealed that RAC1 was highly expressed in tongue cancer tissues, and its expression level was positively correlated with the stage and metastasis of tongue cancer. Meanwhile, histological grade is another important index to judge the malignant degree of tumor. It has been found that RAC1 may regulate the cell transcription program through epigenetic regulation to regulate the differentiation state of tumor cells and promote the occurrence and development of tumor5. The association of RAC1 with histological grades of breast and gastric cancer has been demonstrated17. Our findings further support the notion that the RAC1 positive rate was significantly higher in the low/medium differentiation group than in the high differentiation group, indicating its crucial role in the process of cancer differentiation. However, Eric A. Dik et al. reported that low differentiation was not associated with lymph node metastasis or survival in early lesions18. Additionally, there are contrary opinions, suggesting that the histological grade of the tumor should be considered as an important prognostic factor, with the degree of differentiation significantly affecting lymph node metastasis, interstitial invasion, and nerve invasion19. Our findings did not verify this further. Therefore, the effect of tumor grade on prognosis remains to be studied.

Current research has found that smoking is one of the most common and important risk factors for OSCC20. Previous studies have reported that smoking can activate RAC1 signal through up-regulation of CBX3 and promote the progression of lung adenocarcinoma20. However, our study did not find a correlation between RAC1 expression and smoking. Therefore, we speculate that RAC1 may act as an independent prognostic factor of TSCC and be involved in tumor regulation through other signaling pathways. However, our study did not find a correlation between RAC1 expression and smoking. Therefore, we speculate that RAC1 may act as a potential predictor of TSCC prognosis and be involved in tumor regulation through other signaling pathways.

It has been confirmed that RhoGDI2 can inhibit epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) cascade through RAC1/PAK1/LIMK1 pathway, thereby down-regulating cancer cell migration and invasion21,22. A similar effect was also found in this study when shRNA was used to silence RAC1 in CAL27 cells. Moreover, both in vivo and in vitro, we observed a reduction in PAK1 expression corresponding to the decreased RAC1 expression, and LIMK1 protein levels were also diminished. These findings suggest that RAC1 plays a critical role in regulating the activation of the RAC1/PAK1/LIMK1 signaling pathway. Notably, following RAC1 knockdown, the expression levels of both LIMK1 and its phosphorylated form were significantly reduced compared to the BC and NC groups. However, in all sample groups, the level of phosphorylated LIMK1 was found to be higher than that of total LIMK1. This discrepancy may be attributed to the specific state of the samples. Although LIMK1 undergoes various phosphorylation modifications, including autophosphorylation23, the relationship between LIMK1 and its phosphorylated forms requires further experimental investigation to be fully elucidated.

Conclusion

In this study, we found that RAC1 overexpression in TSCC can promote the progression of tumor metastasis and invasion. We also found that RAC1 is closely associated with poor prognosis of the disease, suggesting that RAC1 plays an important role in the occurrence of tongue cancer. In conclusion, RAC1 may promote the occurrence and development of TSCC by regulating the RAC1/PAK1/LIMK1 signaling pathway, and can be regarded as a potential therapeutic target for TSCC.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

References

Miranda-Filho, A. & Bray, F. Global patterns and trends in cancers of the lip, tongue and mouth. Oral Oncol. 102, 66 (2020).

Depeyre, A. et al. Impairments in food oral processing in patients treated for tongue cancer. Dysphagia 35(3), 494–502 (2020).

Liang, J. et al. RAC1, a potential target for tumor therapy. Front. Oncol. 11, 66 (2021).

Butera, A. et al. The ZNF750-RAC1 axis as potential prognostic factor for breast cancer. Cell Death Discov. 6(1), 66 (2020).

Lionarons, D. A. et al. RAC1P29S induces a mesenchymal phenotypic switch via serum response factor to promote melanoma development and therapy resistance. Cancer Cell 36(1), 68 (2019).

Sauzeau, V., Beignet, J. & Bailly, C. RAC1 as a target to treat dysfunctions and cancer of the bladder. Biomedicines 10(6), 66 (2022).

Lin, Y. et al. Identification of potential key genes for HER-2 positive breast cancer based on bioinformatics analysis. Medicine 99(1), 66 (2020).

Patel, V. et al. Persistent activation of RAC1 in squamous carcinomas of the head and neck: Evidence for an EGFR/Vav2 signaling axis involved in cell invasion. Carcinogenesis 28(6), 1145–1152 (2007).

Yamazaki, M. et al. RAC1-dependent phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by oral squamous cell carcinoma cells: A possible driving force for tumor progression. Exp. Cell Res. 392(1), 66 (2020).

Cabrera, M. et al. Pharmacological RAC1 inhibitors with selective apoptotic activity in human acute leukemic cell lines. Oncotarget 8(58), 98509–98523 (2017).

Onesto, C., et al. Characterization of EHT 1864, a novel small molecule inhibitor of Rac family small GTPases, In Small Gtpases in Disease, Pt B (editors W.E. Balch, C.J. Der, A. Hall) 111 (2008).

Pickering, K. A. et al. A RAC-GEF network critical for early intestinal tumourigenesis. Nat. Commun. 12(1), 66 (2021).

Xia, L. et al. Diallyl disulfide inhibits colon cancer metastasis by suppressing RAC1-mediated epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Oncotargets Therapy 12, 5713–5728 (2019).

Zhou, Y. et al. RAC1 overexpression is correlated with epithelial mesenchymal transition and predicts poor prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Cancer 7(14), 2100–2109 (2016).

Skvortsov, S. et al. RAC1 as a potential therapeutic target for chemo-radioresistant head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC). Brit. J. Cancer 110(11), 2677–2687 (2014).

Liu, M. et al. RAP1-RAC1 signaling has an important role in adhesion and migration in HNSCC. J. Dent. Res. 99(8), 959–968 (2020).

Eiden, C. & Ungefroren, H. The ratio of RAC1B to RAC1 expression in breast cancer cell lines as a determinant of epithelial/mesenchymal differentiation and migratory potential. Cells 10(2), 66 (2021).

Dik, E. A. et al. Resection of early oral squamous cell carcinoma with positive or close margins: Relevance of adjuvant treatment in relation to local recurrence Margins of 3 mm as safe as 5 mm. Oral Oncol. 50(6), 611–615 (2014).

Cariatia, P. et al. Impact of histological tumor grade on the behavior and prognosis of squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 123(6), E808–E813 (2022).

Ford, P. J. & Rich, A. M. Tobacco use and oral health. Addiction 116(12), 3531–3540 (2021).

Zeng, Y. et al. Knockdown of RhoGDI2 represses human gastric cancer cell proliferation, invasion and drug resistance via the RAC1/Pak1/LIMK1 pathway. Cancer Lett. 492, 136–146 (2020).

Yamazaki, M. et al. Rac1 activation in oral squamous cell carcinoma as a predictive factor associated with lymph node metastasis. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 28(9), 1129–1138 (2023).

Arber, S. et al. Regulation of actin dynamics through phosphorylation of cofilin by LIM-kinase. Nature 393(6687), 805–809 (1998).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number 81502340).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Zongxuan He, Hongyu Han, Wei Shang and Lin Wang. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Zongxuan He and Kai Song. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University (approval numbers QYFY-WZLL-28181). The Ethical approval for animal survival was provided by the Qingdao University Laboratory Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee (No.20230529C576J701118002).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, Z., Song, K., Han, H. et al. RAC1 promotes the occurrence and development of tongue squamous cell carcinoma by regulating RAC1/PAK1/LIMK1 signaling pathway. Sci Rep 15, 8831 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92538-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92538-z