Abstract

Interoception, the ability to perceive internal bodily signals, involves various mental processes. This study investigated moments when individuals experienced a change in their interoceptive state. Interoception affects the subjective feelings of emotions. However, whether changes in interoceptive processing occur when visceral changes are perceived as interoceptive sensations remains unclear. This study examined the psychophysiological markers of perceptual changes in the interoceptive state using heartbeat evoked potentials (HEP). Emotional photos were viewed by participants who were asked whether they experienced changes in their interoceptive state. The results showed that the HEP amplitude increased when participants had subjective awareness of changes in their interoceptive state. Notably, the HEP amplitude did not correlate with individual differences in interoceptive accuracy measured by the heartbeat counting task. When individuals perceive changes in their interoceptive state, this perception is reflected in the HEP amplitude. Multiple aspects of interoception are related to the emotional recognition and conscious attention to changing bodily states.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Interoception, the ability to sense internal bodily signals, is an essential aspect of psychology1. Afferent signals from the body are related to various psychological phenomena, including pain perception2, empathy3, decision-making4,5, attentional processing4, orientation of thought5,6, memories of episodes and events7, and many other mental processes8,9,10. Interoception is also related to psychiatric traits, including anxiety11, depression12, and alexithymia13. The most well-known psychological phenomenon in which interoception plays a significant role is the subjective feeling of emotion1,14,15,16,17,18. The theory that emotions are related to the internal body state was proposed more than 100 years ago by William James19 and remains respected today. The importance of interoception in emotions has been highlighted through the recognition of emotions and the level of arousal in emotional experience20. Recent studies have identified three individual interoceptive differences: interoceptive accuracy, sensibility, and awareness21. Interoceptive accuracy refers to the extent to which individuals can accurately perceive interoceptive signals, measured as an objective indicator. Interoceptive sensibility is the tendency to focus internally on one’s interoceptive state, while interoceptive awareness is a metacognitive aspect of interoception.

Interoception, measured using a heartbeat counting task, is categorized as interoceptive accuracy and has been widely used in experimental studies. One aspect of interoceptive research concerns how information from interoception is transmitted and processed in the brain and how it should be measured. Typical interoceptive accuracy measurements are often performed in the resting state, without meaningful changes in autonomic reactivity. However, there is no evidence that the processing of an interoceptive signal with and without distinct autonomic reactivity is the same22,23.

Interoceptive accuracy in the resting state is affected by knowledge and perception24. Furthermore, even without distinct changes, the autonomic state changes continuously. This study focused on the psychophysiological activity that occurs when people feel changes in their interoceptive states. While perception of the interoceptive state occurs without consciousness, it can be raised consciously. The perception of changes in the interoceptive state in an emotional situation may differ from the perception of those changes in a non-emotional situation.

To consider interoceptive processing without requiring subjective responses, it is essential to elucidate the moment at which people experience changes in their interoceptive states. Heartbeat evoked potentials (HEP) effectively investigate objective and implicit interoception in emotional situations. HEP is an electroencephalographic measure that calculates the grand average of electroencephalograph data, typically from the R-peaks of the electrocardiograph25. Although the exact phenomena reflected by HEP are still debated, reviews have suggested that HEP is related to afferent signals from the cardiovascular system26,27,28,29. HEP amplitude is associated with a focus on the internal body30,31,32 and somatosensory perception33,34, in addition to individual differences in interoceptive accuracy35, major depressive disorder36, and borderline personality disorders37. HEP amplitude is also related to various emotional and cognitive processes, such as empathy3, attractiveness and interests38, pain perception39, metacognition40, and self-consciousness41. HEP also helps identify the state of the body, from rapid eye movement sleep42,43 to post-comatose states44. Dipole localization further suggests that the anterior cingulate cortex, right insula, prefrontal cortex, and left secondary somatosensory cortex are sources of HEP45. Studies have also suggested that HEP is involved in emotional recognition, in which positive stimuli have larger amplitudes than negative stimuli46. Situations in which the HEP is measured are not limited to the resting state but extend to tasks ranging from simple activities to those that elicit emotions. These results indicate that interoceptive signals from the cardiovascular system are associated with various states and that HEP reflects the interoceptive processing of the cardiovascular system. Therefore, HEP can be used as an indicator of how interoceptive signals processing changes when alterations occur in an interoceptive state. Prior studies have indicated that HEP amplitude is enhanced when participants focus on the internal body30,31,47. We hypothesized that HEP amplitude would differ according to the subjective awareness of interoceptive state changes, suggesting that subjective recognition of interoception is represented in the brain process.

In this study, we aimed to investigate how the perception of interoceptive state changes occurs during an emotional situation and whether it changes in accordance with the HEP, a physiological measure of interoception. When the participants viewed the emotional pictures, they were asked whether they felt changes in their internal body states, including heart rate, respiration, gustatory responses, and other autonomic responses. HEP was also measured to investigate these relationships, as it reflects subjective attention to the internal body27. HEP was recorded while the participants viewed emotional pictures. We hypothesized that a greater HEP amplitude would be observed when the participants experienced changes in their interoceptive states. To determine whether this awareness of interoceptive state changes was associated with the subjective index of interoception, we compared the HEP amplitude and individual differences in interoceptive accuracy using the heartbeat counting task score. In prior studies on emotions, although poor perceivers felt some emotional strength, they experienced relatively less than good perceivers14,17. Our study was limited to situations in which individuals experienced physical changes in the body, irrespective of the accuracy and frequency of cardiac interoception. In this case, the difference in HEP was predicted to reflect the perception of internal body changes within individuals.

Results

Correlation between heartbeat counting task and emotional task scores

First, we asked participants to report whether they felt changes in their interoceptive state when they saw emotional pictures and whether these changes were related to interoceptive accuracy. The average percentage of pictures in which participants perceived interoceptive state changes was 30.95% (SD = 15.05). The average score for the heartbeat counting task was 0.66 (SD = 0.23), and the median score was 0.69.

We further examined whether there was a correlation between the heartbeat counting task scores and the ratio of trials that made participants feel bodily changes; however, we found no significant correlation (r (32) = 0.11, p = 0.56; Fig. 1). To determine whether changes in heart rate were related to the HEP, we conducted an ANOVA of the four heartbeats following image presentation to determine whether there was a difference in heart rate changes between the trials in which the participants did or did not perceive a change in their interoceptive state. There was a significant interaction between whether the participants felt a change in their interoceptive state and the course of their heartbeat, with participants demonstrating an increased heart rate when they felt a change in their interoceptive state during the third and fourth heartbeats after the image presentation. Additionally, the heart rate decreased during the second and third heartbeats when participants felt a change in their interoceptive state (F(3, 93) = 2.83, p = 0.04, pη2 = 0.08, Fig. 2).

Correlations between interoceptive accuracy measured by the heartbeat counting task and interoception of changes in the body during an emotional state. The heartbeat counting task measures interoceptive accuracy in a silent state. Therefore, interoception in the emotional state may differ from that in the heartbeat counting task. We calculated the correlation between the heartbeat counting task and the percentage of participants who experienced a change in their interoceptive states. There was no significant difference between the two scores, suggesting that interoception in an emotional state may reflect different aspects of interoception measured in the resting state.

Comparison of heart rates when participants felt changes in their interoceptive state while viewing emotional pictures. This graph shows participants’ heart rate following pictures presentation during the emotional task. When the participants felt a change in their interoceptive state, their heart rate decreased during the second and third heartbeats after picture presentation. Notably, there was a difference in heart rate when participants did and did not feel a change in their interoceptive state during the third and fourth heartbeats.

HEP results

The HEP results were compared when the participants felt and did not feel changes in their interoceptive states when looking at emotional pictures. The average number of epochs in which the participants felt a change in their interoceptive state was 355.03 (SD = 190.86). In contrast, the average number of epochs in which the participants did not feel a change in their interoceptive state was 778.88 (SD = 210.5). Three participants whose number of epochs in which they experienced an interoceptive state was less than 100 were excluded. We conducted a cluster-based permutation test to compare the HEP results when participants experienced and did not experience changes in their interoceptive states while looking at emotional pictures. We analyzed all electrodes and found significant differences in the HEP between 428–484 ms and 492–544 ms for several left-frontal electrodes (E8–E14 in the EGI number). The average waveforms of the seven electrodes are shown in Fig. 3a, and the mean amplitudes over a significant time range are shown in Fig. 3b. Topographic maps were created for these periods, and negative potentials were observed in this area (Fig. 3c). These results suggest that the HEP negatively increased when participants experienced a change in their interoceptive state.

Waveform and mean amplitude of the HEP when participants felt changes in their interoceptive state while viewing emotional pictures. (a) Amplitude of the average HEP measured at the left frontal electrodes when participants experienced changes in their interoceptive state while looking at emotion-inducing pictures. The orange area indicates the latency with a significant HEP difference between when participants did and did not feel a change in their interoceptive state. (b) The mean HEP amplitude in the left frontal channels is in the 428–544 ms range (orange area of (a)). Greater negative amplitudes were observed when participants felt changes in their interoceptive state. (c) Topography map of where there was a significant HEP difference between when participants did and did not feel a change in their interoceptive state (428–544 ms, orange areas).

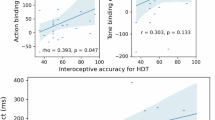

To examine whether the HEP amplitude during interoceptive state changes was related to interoceptive accuracy, we conducted a correlation analysis by calculating the mean amplitude of the HEP in the left-frontal electrodes (428–544 ms). Overall, there were no significant correlations between the mean amplitude of the HEP and the heartbeat counting task score when the participants felt changes in their interoceptive state (r (28) = − 0.26, p = 0.17), while participants did not perceive any changes in their interoceptive state (r (28) = − 0.13, p = 0.49), and the difference of HEP between the trials that participants did and did not feel the change in their interoceptive state (r (28) = − 0.20, p = 0.20; Fig. 4).

Correlations between the heartbeat counting task score and the mean amplitude difference in HEP. To examine whether interoceptive accuracy was related to the amplitude of HEP during the emotional task, we conducted a correlation analysis between the heartbeat counting task scores and the difference in mean HEP amplitudes in the 428–544 ms range in the left frontal electrodes, when participants did or did not experience changes in their interoceptive state while viewing the emotional pictures. There was no significant correlation between these two scores.

Discussion

This study aimed to examine how the perception of changes in the interoceptive state occurs and whether it is associated with HEP. Therefore, we measured HEP while the participants viewed emotion-inducing pictures and asked whether they felt changes in their interoceptive states. We found that the mean HEP amplitude increased when participants experienced a change in their interoceptive state.

Our results indicate that when people perceive changes in their interoceptive state, this perception increases HEP amplitudes. Previous studies have suggested that HEP amplitudes increase during explicit attention to the body, such as in the heartbeat counting task, compared to when focusing on the external environment30 or watching one’s body on a computer monitor48. Another study suggested that focusing on another person’s face increases the HEP amplitude3. Our results are consistent with those of previous studies, suggesting that HEP amplitude increases when participants focus on their bodies during a task30,47. Because the emotional task presented images that induced emotion, the changes in the interoceptive state drew attention to the internal body, resulting in a larger HEP. We found that the heart rate decreased when the participants felt a change in their interoceptive state. A previous study on attention and cardiac activity claimed that attention to the environment, including emotional stimuli, leads to cardiac slowing49. When salient emotional stimulus induces an emotional response, attention is considered to be directed toward that exteroceptive and the associated interoceptive state. In this case, decreasing heart rate will reflect responses to both the emotional stimulus and interoceptive state, and HEP will thus reflect the detection of interoceptive changes during the emotional recognition process. These results suggest that the interaction of exteroception and interoception influences emotional recognition and autonomic changes.

A noteworthy feature of our results is the difference in the HEP of the left electrode. Because interoception has a strong relationship with the right anterior insula16, right electrodes are often chosen as a region of interest. Conversely, the left anterior insula involves emotion and integrating cognitive aspects50. Furthermore, our study showed that the HEP reflects subjective awareness of changes in the interoceptive state in emotional situations when attention is directed toward the internal body state. This tendency can be observed in emotional situations, indicating that perceptions of the interoceptive state occur when individuals are in an emotional situation. Although many studies have examined afferent signals and emotional representations, whether the perception of changes in interoceptive state occurs when emotional stimuli are presented has not yet been adequately discussed. Thus, our study suggests that reference to the internal body state and actual perception occur interactively with subjective feelings of emotion.

The present study did not find a correlation between heartbeat counting score and HEP amplitude during the emotional task. Similarly, there was no correlation between the heartbeat counting score and the number of pictures in which the participants felt a change in their interoceptive state. These results support our hypothesis that interoceptive processing differs when there are changes in participants’ bodily state. The heartbeat counting task is a measure of interoception without distinct autonomic reactivity, whereas the emotional task in this study measures interoception with changes in participants’ internal body state. Therefore, these results suggest that interoception has multiple dimensions, one of which is the perception of the resting state or change in the interoceptive state.

This study has several limitations. First, we did not inquire about subjective valence or arousal during the experiment. This is an important experimental limitation because it is possible that asking about changes in the internal body state would affect the evaluation of valence and arousal in the pictures. It is also possible that the evaluation of the picture affected the interoceptive sensation; in this case, the participants may have decided that they perceived somatic changes because the picture caused high arousal. In addition, this study could not discriminate the actual interoceptive sensation from knowledge of interoception. Because the participants focused on their internal bodies to detect changes in their internal body state, it is most likely that this sensation occurred through an afferent signal. However, some individuals know how often their bodies autonomously respond to emotional stimuli51. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that top-down knowledge affects interoceptive sensations. In future studies, it will be important to specify the modality of interoception experienced by participants during the experiment. A previous study suggested that the respiratory cycle phase is related to the amplitude of the HEP52. Because cardiac activity may intricately interact with other interoceptive modalities, we did not limit changes in cardiac state. Instead, we asked the participants about a wide range of interoceptive sensations. Although HEPs are thought to reflect afferent signals from the cardiovascular system, the body changes experienced by the participants may not stem from the cardiovascular system. Therefore, HEP may reflect signals from such a state or reflect the general state of interoception. If it is possible to determine the relationship between the modalities of interoception and source of HEP34,53,54 by measuring the psychophysiological signals of other modalities, such as respiration, it will also be possible to identify the influence of interoception on emotion recognition in more detail.

In conclusion, our study indicates that HEP reflects the perception of changes in the interoceptive state in an emotional situation. The results of the present study suggest that interoceptive processing in the resting and emotional states differs. Therefore, it will be essential to elucidate interoceptive processing in active state to clarify the role of interoceptive processing in emotional recognition. Future studies should seek to identify the components of interoception that HEP reflects to clarify the role of interoception in emotions.

Methods

Participants

This study was approved by the Keio University Research Ethics Committee (No. 15012–2), and all experiments were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. We performed a priori power analysis for the sample size estimation for t-tests based on our study design using GPower 3.155, assuming that the study had a medium effect size (0.5) based on Cohen’s criteria56. For an alpha of 0.05 and power of 0.80, a sample size of at least 34 was considered necessary. A total of 35 graduate and undergraduate students from Keio University participated in the experiment. One participant was excluded for not completing the task, and another was excluded due to poor ECG readings. The mean age of the participants was 20.79 years (standard deviation [SD] = 1.58). Of the 33 participants, 10 were men and 23 were female. Before the experiment, all participants provided written informed consent.

Stimulus

Pictures were used to induce emotions during the emotional tasks. We used 155 images from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS)57 and 85 from the Open Affective Standardized Image Set (OASIS)58. The file names of the images used are listed in the Supplementary Material.

Experimental procedures

Participants performed two main tasks: a heartbeat counting task and an emotional task. The heartbeat counting task is widely used to measure interoceptive accuracy59. The participants were asked to silently count their heartbeats during the task, during which they were asked not to touch their neck, wrist, or other body parts that might have facilitated their perception of their heartbeats. All participants performed six trials, each with a duration of 25 s, 35 s, or 45 s. The start and end of each trial were recorded on a computer. After each trial, the participants reported the number of heartbeats they counted during the trial. Participants were instructed not to guess or estimate the number of heartbeats even if they could not perceive their heartbeat60.

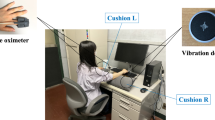

In the emotional task, the participants were asked whether they felt a change in their interoceptive state while watching emotional pictures (Fig. 5). When participants started the trial, a fixation cross appeared for 500 ms (fixation). The emotional picture appeared for 2000 ms (emotional stimulus), followed by a blank screen for 2000 ms (post-emotional phase). The participants were asked whether they felt changes in their interoceptive state while looking at the pictures (response phase, Fig. 4). Participants responded “yes” if they perceived an interoceptive state change, including changes in their heartbeat, rhythm of respiration, shrinking of the stomach, becoming pale, or other changes in their bodies. Participants responded “no” if they did not experience any changes in their interoceptive state. After responding, a 2000 ms inter-trial interval was provided before the starting screen appeared. However, the participants were instructed to start the next trial when they felt their bodies were in a normal state. Participants viewed all 240 pictures. HEP was recorded during the emotional phases.

Overview of the emotional task procedure. An emotional task was conducted to measure the HEP when participants experienced changes in their interoceptive state. In the emotional phase, images that induced emotion were presented for 2000 ms. Then, after the 2000 ms interstimulus interval (post-emotional phase), participants were asked whether they felt a change in their interoceptive state, including changes in their heartbeat, rhythm of respiration, shrinking of the stomach, becoming pale, or other changes in their bodies that could not be explained. The participants were instructed to start the next trial when they felt that their bodies were in a normal state. HEP was recorded during the emotional and post-emotional phases.

EEG and ECG recording

Electroencephalography (EEG) and ECG were performed during the tasks. EEG activity was continuously recorded using a 64-channel active electrode system (HydroCel GSN, EGI) at a sampling rate of 500 Hz. The electrode configuration used was a GSN64 v1.0. The Cz electrode served as a reference for recording. We did not use eye movement electrodes or conduct online filtering while recording the EEG data. The ECG was recorded using a polygraph input box (EGI) at a sampling rate of 500 Hz using lead II. The Ag/AgCl electrodes were attached to the participants’ right and left legs.

During the experiment, the participants sat on a chair in a soundproof room, wore an EEG cap, and attached an ECG electrode. A monitor (REV A03, DELL) was placed in front of the participant (approximately 60 cm away), on which the stimuli were presented. The visual angle of the stimuli was approximately 26°. The stimuli were presented via a presentation (Neurobehavioral Systems) on a computer (Optiplex 7040, DELL).

EEG preprocessing

Offline EEG data were processed using EEGLAB (EEGLAB ver. 2023, University of San Diego, San Diego, CA)61. Continuous EEG data were down-sampled to 250 Hz and re-referenced to a common average reference. Data were band-pass filtered between 0.1 and 30 Hz. Cardiac field artifact (CFA) rejection is a known problem when measuring HEP because it is locked by an R-wave, a solid electrical activity62,63. To remove CFAs and other significant artifacts (e.g., blink artifacts), we used independent component analysis to separate the artifact components from the EEG components and ICLabel64 to classify the artifacts. IClabel is a plugin that automatically determines whether an IC is most likely a component or artifact and can establish reliable criteria for IC classification, which previously relied on the researcher’s judgement. The ICA was excluded if it was determined to be muscle, eye, line, or channel noise, with a probability of more than 80% on ICLabel, or cardiac artifacts, with a probability of more than 60%. Noisy EEG channels were interpolated. The average number of interpolated channels used in this study was 2.11 (SD = 1.65, maximum = 7). The ECG was analyzed using an EDF browser to detect the R-peaks. A 1-Hz high-pass filter was applied to the ECG data, and HEPs were extracted from the R-peaks in the time range of − 200 to 600 ms.

Statistical analyses

To measure individual interoceptive accuracy scores, we conducted a heartbeat counting task using the formula outlined in a previous study17. Scores closer to 1 indicated that the participants had accurate interoception.

In the emotional task, we calculated the perception of changes in the interoceptive state by calculating the percentage of stimuli among the 240 pictures in which participants felt changes in their interoceptive state. Correlation between the scores on heartbeat counting and emotional tasks was then evaluated.

For HEP analysis, we conducted a non-parametric cluster-based permutation test65. The permutation test creates a randomly assigned distribution of time and distance and compares the created distribution with the actual data. This analysis, which considers the temporal adjacency and distance of the electrode, provides an efficient method for examining the HEP without a priori selection of spatial and temporal locations41,65. The analysis was conducted using the Fieldtrip-lite66 toolbox (v20240111) in EEGLAB. The adjacent electrode that showed significant differences in the same time range was considered a priority cluster. Two-tailed permutations were performed 4000 times.

Data availability

Data is available at OSF (https://osf.io/j9cyt/?view_only=05c5d7f79d344b86a2891072e26a4cbc).

References

Critchley, H. D., Wiens, S., Rotshtein, P., Öhman, A. & Dolan, R. J. Neural systems supporting interoceptive awareness. Nat. Neurosci. 7, 189–195 (2004).

Di Lernia, D., Serino, S. & Riva, G. Pain in the body. Altered interoception in chronic pain conditions: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 71, 328–341 (2016).

Fukushima, H., Terasawa, Y. & Umeda, S. Association between interoception and empathy: Evidence from heartbeat-evoked brain potential. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 79, 259–265 (2011).

Matthias, E., Schandry, R., Duschek, S. & Pollatos, O. On the relationship between interoceptive awareness and the attentional processing of visual stimuli. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 72, 154–159 (2009).

Ito, Y., Shibata, M., Tanaka, Y., Terasawa, Y. & Umeda, S. Affective and temporal orientation of thoughts: Electrophysiological evidence. Brain Res. 1719, 148–156 (2019).

Sakuragi, M., Shinagawa, K., Terasawa, Y. & Umeda, S. Effect of subconscious changes in bodily response on thought shifting in people with accurate interoception. Sci. Rep. 13, 16651 (2023).

Terasawa, Y. & Umeda, S. The impact of interoception on memory. In Memory in a Social Context (eds Tsukiura, T. & Umeda, S.) 165–178 (Springer, 2017).

Craig, A. D. How do you feel—now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 59–70 (2009).

Khalsa, S. S. et al. Interoception and mental health: A roadmap. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 3, 501–513 (2018).

Brewer, R., Murphy, J. & Bird, G. Atypical interoception as a common risk factor for psychopathology: A review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 130, 470–508 (2021).

Domschke, K., Stevens, S., Pfleiderer, B. & Gerlach, A. L. Interoceptive sensitivity in anxiety and anxiety disorders: An overview and integration of neurobiological findings. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 30, 1–11 (2010).

Paulus, M. P. & Stein, M. B. Interoception in anxiety and depression. Brain Struct. Funct. 214, 451–463 (2010).

Kano, M. & Fukudo, S. The alexithymic brain: The neural pathways linking alexithymia to physical disorders. Biopsychosoc. Med. 7, 1 (2013).

Dunn, B. D. et al. Listening to your heart: How interoception shapes emotion experience and intuitive decision making. Psychol. Sci. 21, 1835–1844 (2010).

Seth, A. K. & Friston, K. J. Active interoceptive inference and the emotional brain. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 371, 20160007 (2016).

Terasawa, Y., Fukushima, H. & Umeda, S. How does interoceptive awareness interact with the subjective experience of emotion? An fMRI study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 34, 598–612 (2013).

Terasawa, Y., Moriguchi, Y., Tochizawa, S. & Umeda, S. Interoceptive sensitivity predicts sensitivity to the emotions of others. Cogn. Emot. 28, 1435–1448 (2014).

Wiens, S., Mezzacappa, E. S. & Katkin, E. S. Heartbeat detection and the experience of emotions. Cogn. Emot. 14, 417–427 (2000).

James, W. What is emotion? 1884. In Readings in the History of Psychology. (ed. Dennis, W.) 290–303 (Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1948). https://doi.org/10.1037/11304-033.

Pollatos, O., Traut-Mattausch, E., Schroeder, H. & Schandry, R. Interoceptive awareness mediates the relationship between anxiety and the intensity of unpleasant feelings. J. Anxiety Disord. 21, 931–943 (2007).

Garfinkel, S. N., Seth, A. K., Barrett, A. B., Suzuki, K. & Critchley, H. D. Knowing your own heart: Distinguishing interoceptive accuracy from interoceptive awareness. Biol. Psychol. 104, 65–74 (2015).

Zamariola, G., Frost, N., Van Oost, A., Corneille, O. & Luminet, O. Relationship between interoception and emotion regulation: New evidence from mixed methods. J. Affect. Disord. 246, 480–485 (2019).

Corneille, O., Desmedt, O., Zamariola, G., Luminet, O. & Maurage, P. A heartfelt response to Zimprich et al. (2020), and Ainley et al. (2020) ’s commentaries: Acknowledging issues with the HCT would benefit interoception research. Biol. Psychol. 152, 107869 (2020).

Desmedt, O., Luminet, O. & Corneille, O. The heartbeat counting task largely involves non-interoceptive processes: Evidence from both the original and an adapted counting task. Biol. Psychol. 138, 185–188 (2018).

Weitkunat, R. & Schandry, R. Motivation and heartbeat evoked potentials. J. Psychophysiol. 4, 33–40 (1990).

Engelen, T., Solcà, M. & Tallon-Baudry, C. Interoceptive rhythms in the brain. Nat. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-023-01425-1 (2023).

Park, H.-D. & Blanke, O. Heartbeat-evoked cortical responses: Underlying mechanisms, functional roles, and methodological considerations. NeuroImage 197, 502–511 (2019).

Coll, M.-P., Hobson, H., Bird, G. & Murphy, J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the relationship between the heartbeat-evoked potential and interoception. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 122, 190–200 (2021).

Tanaka, Y., Ito, Y., Terasawa, Y. & Umeda, S. Modulation of heartbeat-evoked potential and cardiac cycle effect by auditory stimuli. Biol. Psychol. 182, 108637 (2023).

Montoya, P., Schandry, R. & Müller, A. Heartbeat evoked potentials (HEP): Topography and influence of cardiac awareness and focus of attention. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. Potentials Sect. 88, 163–172 (1993).

Petzschner, F. H. et al. Focus of attention modulates the heartbeat evoked potential. NeuroImage 186, 595–606 (2019).

Schandry, R. & Montoya, P. Event-related brain potentials and the processing of cardiac activity. Biol. Psychol. 42, 75–85 (1996).

Al, E. et al. Heart–brain interactions shape somatosensory perception and evoked potentials. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117, 10575–10584 (2020).

Al, E., Iliopoulos, F., Nikulin, V. V. & Villringer, A. Heartbeat and somatosensory perception. NeuroImage 238, 118247 (2021).

Pollatos, O. & Schandry, R. Accuracy of heartbeat perception is reflected in the amplitude of the heartbeat-evoked brain potential. Psychophysiology 41, 476–482 (2004).

Terhaar, J., Viola, F. C., Bär, K.-J. & Debener, S. Heartbeat evoked potentials mirror altered body perception in depressed patients. Clin. Neurophysiol. 123, 1950–1957 (2012).

Müller, L. E. et al. Cortical representation of afferent bodily signals in borderline personality disorder: Neural correlates and relationship to emotional dysregulation. JAMA Psychiatry 72, 1077–1086 (2015).

Fuseda, K. & Katayama, J. A new technique to measure the level of interest using heartbeat-evoked brain potential. J. Psychophysiol. 35, 15–22 (2021).

Shao, S., Shen, K., Wilder-Smith, E. P. V. & Li, X. Effect of pain perception on the heartbeat evoked potential. Clin. Neurophysiol. 122, 1838–1845 (2011).

Kamp, S.-M., Schulz, A., Forester, G. & Domes, G. Older adults show a higher heartbeat-evoked potential than young adults and a negative association with everyday metacognition. Brain Res. 1752, 147238 (2021).

Park, H.-D. et al. Transient modulations of neural responses to heartbeats covary with bodily self-consciousness. J. Neurosci. 36, 8453–8460 (2016).

Billeci, L. et al. Heartbeat-evoked cortical potential during sleep and interoceptive sensitivity: A matter of hypnotizability. Brain Sci. 11, 1089 (2021).

Simor, P., Bogdány, T., Bódizs, R. & Perakakis, P. Cortical monitoring of cardiac activity during rapid eye movement sleep: The heartbeat evoked potential in phasic and tonic rapid-eye-movement microstates. Sleep 44, zsab100 (2021).

Candia-Rivera, D., Catrambone, V., Thayer, J. F., Gentili, C. & Valenza, G. Cardiac sympathetic-vagal activity initiates a functional brain–body response to emotional arousal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119, e2119599119 (2022).

Pollatos, O., Kirsch, W. & Schandry, R. Brain structures involved in interoceptive awareness and cardioafferent signal processing: A dipole source localization study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 26, 54–64 (2005).

Couto, B. et al. Heart evoked potential triggers brain responses to natural affective scenes: A preliminary study. Auton. Neurosci. 193, 132–137 (2015).

Schandry, R., Sparrer, B. & Weitkunat, R. From the heart to the brain: A study of heartbeat contingent scalp potentials. Int. J. Neurosci. 30, 261–275 (1986).

Park, H.-D. et al. Neural sources and underlying mechanisms of neural responses to heartbeats, and their role in bodily self-consciousness: An intracranial EEG study. Cereb. Cortex 28, 2351–2364 (2018).

Libby, W. L. Jr., Lacey, B. C. & Lacey, J. I. Pupillary and cardiac activity during visual attention. Psychophysiology 10(3), 270–294 (1973).

Li, W. et al. Differential involvement of frontoparietal network and insula cortex in emotion regulation. Neuropsychologia 161, 107991 (2021).

Ring, C., Brener, J., Knapp, K. & Mailloux, J. Effects of heartbeat feedback on beliefs about heart rate and heartbeat counting: A cautionary tale about interoceptive awareness. Biol. Psychol. 104, 193–198 (2015).

Salamone, P. C. et al. Interoception Primes emotional processing: Multimodal evidence from neurodegeneration. J. Neurosci. 41, 4276–4292 (2021).

Zaccaro, A., Perrucci, M. G., Parrotta, E., Costantini, M. & Ferri, F. Brain-heart interactions are modulated across the respiratory cycle via interoceptive attention. NeuroImage 262, 119548 (2022).

Fittipaldi, S. et al. A multidimensional and multi-feature framework for cardiac interoception. NeuroImage 212, 116677 (2020).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G. & Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 175–191 (2007).

Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (Academic Press, 2013).

Lang, P. J., Bradley, M. M. & Cuthbert, B. N. International Affective Picture System (IAPS): Affective Ratings of Pictures and Instruction Manual (NIMH, Center for the Study of Emotion & Attention Gainesville, 2005).

Kurdi, B., Lozano, S. & Banaji, M. R. Introducing the open affective standardized image set (OASIS). Behav. Res. Methods 49, 457–470. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-016-0715-3 (2017).

Schandry, R. Heart beat perception and emotional experience. Psychophysiology 18, 483–488 (1981).

Desmedt, O. et al. Contribution of time estimation and knowledge to heartbeat counting task performance under original and adapted instructions. Biol. Psychol. 154, 107904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2020.107904 (2020).

Delorme, A. & Makeig, S. EEGLAB: An open-source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics. J. Neurosci. Methods 134, 9–21 (2004).

Pérez, J. J., Guijarro, E. & Barcia, J. A. Suppression of the cardiac electric field artifact from the heart action evoked potential. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 43, 572–581 (2005).

Arnau, S., Sharifian, F., Wascher, E. & Larra, M. F. Removing the cardiac field artifact from the EEG using neural network regression. Psychophysiology https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.14323 (2023).

Pion-Tonachini, L., Kreutz-Delgado, K. & Makeig, S. ICLabel: An automated electroencephalographic independent component classifier, dataset, and website. NeuroImage 198, 181–197 (2019).

Maris, E. & Oostenveld, R. Nonparametric statistical testing of EEG-and MEG-data. J. Neurosci. Methods 164(1), 177–190 (2007).

Oostenveld, R., Fries, P., Maris, E. & Schoffelen, J. M. FieldTrip: Open-source software for advanced analysis of MEG, EEG, and invasive electrophysiological data. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2011, 1–9 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Funding

This study was supported by the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (JP20H00108), Challenging Research (JP19K21819 and JP22K18264), and Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (JP18H05525).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Ta., Y.Te., and S.U. designed the study. Y.Ta., M.S. and Y.I. conducted the experiments. Y.Ta. programmed the computer tasks, and analyzed the data. All authors interpreted the results. Y.Ta. drafted the manuscript, while all other authors provided critical revisions. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Keio University Research Ethics Committee (No. 15012-2).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tanaka, Y., Ito, Y., Shibata, M. et al. Heartbeat evoked potentials reflect interoceptive awareness during an emotional situation. Sci Rep 15, 8072 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92854-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92854-4