Abstract

Quality of life is a critical outcome in oncology, influencing treatment adherence and patient satisfaction. Haematology patients face psychological challenges, including emotional distress, depression and PTSD, which can affect their quality of life. Resilience and social support are protective factors that help patients cope with these challenges. This study aimed to assess the psychological adjustment of haematology patients by examining psychological outcomes (PTSD and depression), psychological resources (resilience and perceived social support), and quality of life. It also examined correlations between demographic variables, psychological outcomes and resources to identify predictors of quality of life and whether resilience mediates these effects. A sample of 110 haematology patients from three hospital centers in central/southern Italy participated. Data were collected using self-report questionnaires measuring PTSD, depression, resilience, social support and quality of life. Correlational analyses and hierarchical multiple regression were used to explore the relationships between variables, followed by a mediation analysis to examine the role of resilience. Results indicated that QOL was negatively associated with gender, age, PTSD and depression, but positively associated with resilience. Regression analyses showed that quality of life was significantly predicted by resilience, age, depressive symptoms and gender. The mediation model showed that resilience partially mediated the effects of age, gender and depression on QoL. These findings highlight the protective role of resilience in improving quality of life in haematology patients. Despite limitations related to sample size and the use of self-report questionnaires, this study provides valuable insights into the psychological adjustment of haematology patients and highlights the importance of considering psychological resources in oncology care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quality of life (QOL), as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), refers to an individual’s perception of his or her living conditions in relation to the context, culture and value system in which he or she lives, and how these elements relate to personal goals, expectations and concerns1. Quality of life is a broad and multidimensional concept that encompasses a person’s physical condition, psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, environment and spirituality2. It is possible to highlight a significant link between QOL and subjective well-being in that the aspects that are most likely to increase an individual’s level of QOL focus mainly on those aspects that make life particularly pleasant, happy and worth living, such as meaningful work, self-fulfillment or a good standard of living3, above those elements that guarantee mere subsistence, survival and longevity.

The concept of QOL is closely linked to that of health: ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ (WHO, 1948).

In recent decades, studies on QOL in a health context have increased considerably in different contexts, such as health, organizational or educational contexts. In health context, it is possible to speak of Health Related Quality of Life (HR-QOL), which can encompass a wide range of aspects: from general health, physical symptoms, emotional well-being, cognitive functioning to existential and spiritual aspects4.

In the health context, this growing scientific interest has been driven by a progressive evolution of the medical approach, which over time has broadened its focus to include not only quantitative aspects (years of survival, number of relapses, cure rates, etc.), but also the improvements that treatments can bring to the perception of QOL, recognizing the latter as one of the main factors determining the demand for treatment, adherence to treatment regimens and individual satisfaction with treatments5. Quality of life thus becomes a goal of medical interventions in general and rehabilitation programs in particular6.

The most used method of assessing QOL in healthcare is closely linked to the clinical assessment of the patient and their health status, relating physical and mental well-being, disability and work capacity to QOL. However, this does not consider that QOL is not directly related to an individual’s functional status: in fact, patients with the same clinical condition may perceive their QOL very differently, and the impact of care may vary subjectively from one patient to another6. For this reason, a way of assessing QOL that focuses on an individual’s subjective perception of their life has recently been introduced7,8,9. This second approach approaches the concept of person-centered care rather than disease-centered care and allows for a better understanding of the individual patient, including their perceptions, intelligence, philosophy and emotional state4,10.

For this modality to work, it is important that health professionals actively listen to patients’ experiences, seek to understand their perspectives, and check that patients’ self-assessments of their own health and life satisfaction do not differ from doctors’ opinions11.

Olsen et al.12 investigated how QoL varies with gender and age in Europe. No overall gender difference in QoL was found in Northern Europe, but women had slightly lower QoL than men in the other European regions, with the gender difference being most pronounced in Southern Europe. Women’s lower QoL was mainly due to lower control and autonomy. Women had more depressive symptoms than men in all age groups in the four European regions. The higher odds of depressive symptoms were mainly due to higher odds of ‘tearfulness’, ‘depression’ and ‘sleep problems’. In addition, gender differences in QoL increase with age. This may be due to stressors that are more likely to occur in old age, such as widowhood/living alone, poor health, financial pressures and caring, where sex differences often exist to the detriment of women13. The widening gender gap in QoL with age may also be consistent with a survival effect, where healthier men survive into old age14.

In the oncological context, physicians are beginning to recognise QOL as a critical aspect not only of tumor response, survival, time to progression and treatment toxicity, but also in guiding patients in treatment decisions themselves15,16.

Despite the high level of patient interest in their treatment process and the increasing need for honest and considerate discussions about treatment choices and how they perceive life after diagnosis, there is still a reluctance to use QOL measurement tools in clinical practice, often perceived as too complicated, time-consuming or expensive17.

Several studies have shown how the type of treatment chosen and the location of the tumor can alter a patient’s quality of life18,19. However, as the number of people recovering from cancer increases, quality of life also becomes a crucial aspect of understanding the survivorship experience and the ongoing, often prolonged, impact of both the disease and its associated therapies. Indeed, the impact of cancer on a survivor’s life does not end with the completion of primary treatment but can affect all aspects of life from 2 to 26 years after diagnosis20,21, particularly physical health (ability to work and perform normal daily activities such as eating out, washing or dressing) and mental health22.

The course of illness causes the person to experience a series of transformations that require the use of one’s adaptive resources. The way in which the illness affects the patient, both physically and psychologically, is summarized in the concept of emotional distress. This condition involves severe emotional distress of a psychological, social and spiritual nature that can occur during or after treatment and can be chronic and long-term23,24,25. Examples of long-term effects include neuropathy with relative weakness, numbness or pain; fatigue; cognitive or sexual difficulties; high anxiety or depression26. Regardless of when they occur, the long-term and late effects of cancer can have a significant impact on patients’ daily activities and therefore their quality of life27.

Effects that directly affect the psychological sphere of patients include depressive episodes that can emerge and persist during treatment, placing an additional burden on disease management. This complicated picture makes disease control more difficult, compromises treatment adherence, prolongs hospital stays and may negatively affect survival28,29,30,31,32,33. Risk factors for depression in cancer patients include biological aspects such as cancer type, stage, and treatment-related factors; individual factors such as personal family and psychiatric history and personality traits; and social and interpersonal factors such as stressful life events, loneliness, social isolation, low socioeconomic status, and lack of social support34. Patients often tend to hide their feelings to protect themselves from states of distress that are too difficult for them and their loved ones to cope with. Anxiety and fear are common, often accompanied by feelings of anger, bitterness and despair. Symptoms associated with mood disorders and depressive states, such as sadness, emptiness and hopelessness, may be manifested by loss of interest in usual activities and significant people, reduced ability to think or concentrate, feelings of inadequacy, self-evaluation and guilt, and thoughts of death. These experiences are often expressed in behavior and demands that may appear contradictory and inconsistent. Since controlling such emotions requires a great deal of psychological energy, it is not uncommon for patients to find themselves lacking the necessary resources to cope with work and daily activities35,36. In this delicate phase, the factors that can trigger a crisis include the perception of vulnerability and threat to one’s existence, combined with the fear of having to leave loved ones prematurely without having completed some basic life tasks37.

One of the most common problems in cancer patients is Cancer-Related Fatigue (CRF), which is closely related to depression and quality of life. It is the most persistent symptom over time and the one with the greatest impact on daily life, perceived as worse than pain, nausea and depressive states. This condition has a negative impact on both the physical and psychological state of the patient, and its negative effects also extend to the social and economic sphere, significantly affecting the quality of life of the cancer patient and those around them. At the same time, patients perceive a lack of recognition of their condition by those around them and a lack of understanding of their difficulties, which can lead to feelings of detachment and inadequacy in family and social relationships38.

As the number of cancer survivors increases, the long-term psychological effects of diagnosis and treatment are more pronounced than in the past. In response, in 1994 the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) expanded the criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) to include the diagnosis of a life-threatening illness as a traumatic event. Cancer, which is characterized by multiple and chronic stressors, is a significant threat, but in the fifth edition of the DSM (DSM-5) it is no longer considered a traumatic event warranting a diagnosis of PTSD unless the discovery of the disease is sudden and catastrophic. Despite this change in classification, the DSM-IV definition led to nearly two decades of research on PTSD in cancer patients from 1994 to 2013, and some researchers continue to use the DSM-IV criteria to study cancer populations39.

Current research focuses on the personal strategies and resources that individuals use to cope with difficult and stressful situations such as illness, bereavement or major life changes. These elements, known as ‘protective factors’, help individuals to cope as well as possible with the difficulties associated with illness.

One of these protective factors is resilience, which is the combination of elements that help the individual to regain functioning after a damaging event or significant adversity40. Rutter41 suggested that resilience is the result of protective processes that, while not eliminating risk or adversity, enable the individual to cope with it more effectively. In this view, illness can be seen as a potential catalyst for positive change, rather than simply leading to negative psychosocial outcomes.

Related to resilience is the concept of Post Traumatic Growth (PTG), defined as the positive psychological change that occurs as a result of coping with extremely challenging or traumatic life events42,43. A traumatic event creates an imbalance that activates a range of adaptive strategies, including the conscious processing of the experience, which in some cases allows a positive view of self, others and the world to develop. The main signs of this growth include increased personal resilience, improved ability to relate to others, openness to new opportunities, a deeper spiritual connection and a renewed appreciation of life44.

Home environment and the quality of social relationships also play a crucial role in adaptation to illness, influencing how individuals perceive and cope with life events. This area includes concepts such as the exchange of supportive interactions, perceptions of support received, social integration and loneliness (understood as the discrepancy between desired and actual social relationships). Support from interpersonal relationships is crucial in counteracting the effects of stress, promoting physical and psychological well-being, and increasing self-esteem through the perception of a secure base both externally and internally45,46.

In the oncology setting, social and family support is not limited to the provision of resources and services to the patient, but also includes the communication of care, love, appreciation and acceptance. This support makes the patient feel part of a community and mutual exchange, and acts as a buffer in crisis situations47.

Objectives and hypotheses

The aims of the present study, within this research framework, were to:

-

(a)

Assess the psychological adjustment of hematology patients using the following variables: psychological outcomes (PTSD and depression), psychological resources (resilience and perceived social support) and quality of life;

-

(b)

To assess correlations between age variables (age, gender), psychological outcomes (depression symptoms; PTSD symptoms); psychological resources (perceived social support and resilience) and perceived quality of life in hematology patients;

-

(c)

To assess which variable among: age variables (age, gender), psychological consequences (symptoms of depression; symptoms of PTSD), and psychological resources (perceived social support and resilience) predicts quality of life in hematology patients;

-

(d)

To assess whether resilience mediates the effect of the predictors on perceived quality of life.

We hypothesized that:

(H1) Hematology patients will have high levels of PTSD symptoms and depression, low levels of resilience and social support, and low levels of quality of life.

(H2) Older patients and women will have lower levels of quality of life.

(H3) Patients with higher levels of depressive symptoms and PTSD have lower levels of QoL.

(H4) Patients with higher levels of social support and resilience have higher QoL.

(H5) Quality of life is predicted by both demographic variables, clinical symptoms and patient resources.

(H5) Resilience mediates the effect of demographic and clinical variables on QoL.

Method

Participants

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients with hematological malignancies; (2) The diagnosis of cancer recived at least three months before the study; (3) life expectancy over 6 months; (4) Age over 18 years; (5) Primary school or above education level, able to correctly communicate and answer the questions included in the tests. The following exclusion criteria were applied: (1) Presence of psychiatric diseases; (2) Patients with cognitive or physical difficulties that prevented independent completion of the questionnaires (3) patients admitted for non-haematological conditions or with severe comorbidities unrelated to haematological cancer.

Of the 207 patients approached from three hospital centers in central/southern Italy, 82 declined to participate. 15 patients dropped out during the study. A total of 110 patients responded and provided written informed consent filled the questionnaires.

Participants had a mean age of 66.60 years (SD = 15.74), ranging from 22 to 98 years; they were predominantly male (59.1%), Italian (78%), married (70%), with children (77.27%), with a low to medium level of education (40.91% high school diploma), and employed (73.64%).

64.6% (n = 71) of the patients were admitted to medical wards, while the remaining 35.4% (n = 39) were treated in day hospitals. 70.9% received chemotherapy, while the remaining 29.1% received supportive therapies (hemotransfusion, nutritional therapies, etc.) (Table 1).

Instruments

Demographic characteristics: We recorded participants’ age, ethnic background, level of education, number of children, marital/relationship status, kind of treatment and therapies received.

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II)48 Italian validation by Ghisi et al.49: Depressive symptoms were assessed using the BDI-II, a 21-item tool that covers the cognitive, affective, motivational and behavioral components of depression. Each item is rated on a four-point scale from 0 (never) to 3 (always). The total score (maximum 63 points) is the sum of the scores for the individual items. Based on the Italian validation study, a cut-off score of ≥ 12 was used to establish whether depression was present. Scores from 13 to 19 indicate mild depression; from 20 to 28, moderate depression; and from 29 to 63, severe depression. Cronbach’s α coefficient has ranged from 0.80 to 0.87 in normative or clinical samples48. In this study, the α coefficient was 0.87.

Los Angeles Symptom Checklist (LASC)50 The LASC is a 43-item self-report instrument. It provides a measure of global distress due to trauma exposure, severity of overall PTSD symptomology, and severity of individual PTSD symptoms (re-experiencing, avoidance/numbing, and hyperarousal). Previous studies found high internal consistency with α coefficients ranging from 0.88 to 0.9550. In the present study, the α coefficient was 0.89.

Resilience Scale for Adult51 Was administered to assess resilience. It is a 33-item self-report scale for measuring protective resilience factors among adults. It applies a seven-point semantic differential scale in which each item has a positive and a negative attribute at each end of the scale continuum. To reduce acquiescence biases half of the items are reversely scored. Higher scores indicate higher levels of protective resilience factors. In the final version, it presents six factors associated with individual-familiar and social dimensions (Perception of self; Planned future; Social competence; Structured style; Family cohesion; Social resources). The RSA has proven to be a reliable scale, with good internal consistency demonstrated by Cronbach’s alpha values which in the various studies vary from 0.79 to 0.88. In our study coefficients were 0.82.

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), Italian validation by Prezza and Principato52,53 The MSPSS is a self-report instrument; it includes 12 items that converge in three dimensions: family, friends, and significant others. Each item is rated on a seven-point Likert-type response format (1 = very strongly disagree; 7 = very strongly agree). A total score is calculated by summing up all the answers. The possible score range is between 12 and 84, the higher the score the higher the perceived social support. The possible score range for the subscales/dimensions is between 4 and 28. Any mean scale score ranging from 1 to 2.9 could be considered low support; a score of 3–5 could be considered moderate support; a score from 5.1 to 7 could be considered high support. Cronbach’s coefficients range from 0.85 to 0.9152. In this research coefficients were 0.89.

EQ-5D54 is a standardized self-report questionnaire that measures health-related quality of life (HRQL). The descriptive system comprises five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. Each dimension has 5 levels: no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems and extreme problems. The patient is asked to indicate his/her health state by ticking the box next to the most appropriate statement in each of the five dimensions. This decision results in a 1-digit number that expresses the level selected for that dimension. The digits for the five dimensions can be combined into a 5-digit number that describes the patient’s health state. The EQ VAS records the patient’s self-rated health on a vertical visual analogue scale where the endpoints are labeled ‘The best health you can imagine’ and ‘The worst health you can imagine’. The VAS can be used as a quantitative measure of health outcome that reflects the patient’s own judgment. Another method of assessing quality of life used in the present study is the application of an algorithm that allows the calculation of a synthetic score (EQ-5D index) of perceived health status. The implementation of this algorithm involves assigning a specific weight to each dimension of health status, which is calculated for a general population using cost-utility analysis techniques. The EQ-5D Index score is calculated by subtracting the relevant coefficients and constants per level of severity from 1000: the closer the score is to 1000, the better the perceived health status. (Table 2).

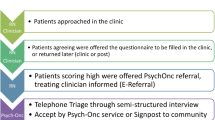

Procedure

Patients were recruited from three hospital facilities, from long stay wards and day hospital wards. This study was carried out in keeping with the Ethics Code of Italian Psychologists and approved by the Ethics Committee of eCampus University. Informed written consent was obtained from participants. The data were handled in keeping with General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), RegulationUE2016/679. All participants received an envelope including the information about the aims of the study, consent forms, a socio-demographic questionnaire, and all the other study questionnaires. Long-term hospitalized patients completed the questionnaires independently and individually in hospital, while day hospital patients filled them at home. Data were collected from January 2023 to February 2024.

Statistical analysis

The descriptive analysis entailed computing participants’ baseline scores for PTSD, depression, resilience, social support and quality of life. To investigate the association between demographics (age, gender), psychological impairments (PTSD and depression symptoms), psychological resources (social support and resilience) and quality of life correlational analysis were performed between all the variables studied. Finally, to examine the last hypothesis, hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted, following the mediational model by55. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 21.

Results

Objective 1: Psychological adaptation of hematology patients

In terms of psychological outcomes, descriptive analyses (Table 3) show average levels of PTSD among study participants50 and predominantly mild to moderate levels of depression symptoms48. In terms of resources, participants show moderate levels of perceived social support and resilience. Finally, they report low to moderate levels of quality of life.

Objective 2: Correlations between age variables, psychological outcomes, resources and quality of life

Correlational analyses show a negative relationship between QoL and gender, age, PTSD and depression. Specifically, it is female patients with higher age and higher levels of PTSD and depression symptoms who report lower levels of quality of life. In contrast, quality of life is positively correlated with resilience levels. No significant correlations between QoL and social support were found (Table 4).

Objective 3: Variables that predict quality of life

The hierarchical multiple regression analysis show that quality of life is firstly predicted by the level of resilience (β = − 0.446; t = 6.540, p = 0.001), secondly by age (β = − 0.326; t = − 4.646, p = 0.001), depressive symptoms (β = − 0.271; t = − 3.452, p = 0.001) and finally by gender (β = − 0.134; t = − 2.136, p = 0.03) (Table 5).

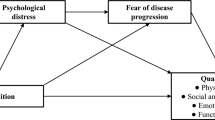

Objective 4: Mediating effect of resilience

Based on the results of the hierarchical multiple regression analyses, a mediation model55 was run, with age, gender and depression symptoms as predictors and level of resilience as a mediator.

The first model shows that age predicts QoL, with older patients perceiving a lower level of QoL. However, resilience partially mediates the effect of age.

Similarly, the second model shows that gender predicts QoL, with women reporting lower levels. However, resilience again acts as a protective factor, partially mediating the effect of gender on QoL.

Finally, the third model shows that depression predicts QoL, with resilience levels partially mediating.

Discussion

Contemporary oncology focuses not only on drug treatment, but also on a broader understanding of the experiences of patients and their families, prioritizing resource allocation, planning and delivery of holistic care that has a significant impact on quality of life. Many studies have highlighted how a patient’s mental state changes with time, disease progression and treatment, and how a positive attitude plays an important role in the recovery process, highlighting the importance of psychological variables in facilitating or, conversely, hindering the care process56,57.

In particular, the measurement of quality of life in cancer patients has been the subject of interest in many studies58,59,60. For example, Montazieri et al.60 conducted a study of 129 lung cancer patients and highlighted that patients’ overall quality of life prior to starting cancer treatment was an important predictor of survival. The study of more than 400 cancer patients by Li et al.61 came to the same conclusion, finding that health-related quality of life was a strong and independent predictor of overall survival.

By specifically analyzing studies involving hematology patients62,63, it becomes clear how certain characteristics of hematological malignancies, such as acute onset, rapid progression, easy recurrence, complex treatment methods and high treatment costs, can seriously affect the physical health, but also the mental health and quality of life of patients. Based on these considerations, our research aimed to assess the psychological adjustment of hematology patients, focusing on the psychological consequences of the disease in terms of depression and PTSD, psychological resources such as resilience and perceived social support, and their impact on perceived quality of life.

In addition, the aim was to assess which variables among demographics, clinical outcomes and psychological resources predict patients’ quality of life and whether resilience plays a protective role.

About the first objective, our data confirm that hematological patients, like patients with other types of cancer, manifest significant levels of depression and PTSD, moderate levels of perceived resilience and social support, and a medium–low quality of life, in line with previous research57,64,65.

Specifically, although not all cancers pose the same level of risk to life, the initial cancer diagnosis is interpreted as a life-threatening experience and may increase the risk of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression.

For example, Amir and Ramati64 found significantly higher rates of PTSD in female breast cancer survivors compared with controls. Lewandowska et al.57 conducted a large survey of 800 patients diagnosed with different types of cancer and found that 50 per cent of them showed symptoms of depression and 48 per cent showed fear and anxiety about the future. Similar findings were reported by Dehkordi et al.66 who showed that the most common problems among cancer patients treated with chemotherapy were fear of the future (29%), thinking about the disease and its consequences (26.5%) and depression (17.5%). Similarly, Nayak et al.67 surveyed more than 700 cancer patients and found that 54.4% of participants reported depression and the majority (98.3%) said they did not feel comfortable participating in social life.

Our data confirms a close relationship between quality of life, age variables, psychological outcomes and resources, in line with previous studies. In particular, we found that female gender, older age and high levels of depression are risk factors that negatively impact patients’ quality of life.

Similarly, Geffen et al.68 conducted a study of 44 patients with Hodgkin’s disease and found that 32% of survivors had partial or complete PTSD and that the diagnosis of PTSD correlated with significantly lower quality of life than patients without PTSD. Similarly, in a large sample of 289 cancer patients, Gold et al.65 found that 45% of the sample had a clinical score of PTSD, which was associated with higher mood disorder scores and lower quality of life scores.

Our results also suggest gender and age differences in QOL perceptions: in particular, female and older patients report lower QOL, confirming what previous research has documented.

For example, Modlinska et al.69 showed that the anxious response to cancer significantly affects QoL in terminally ill patients under the age of 65, with more negative outcomes in older patients due to the greater impact of the disease on daily life and reduced autonomy.

In terms of gender, studies by Grassi et al.46 had already found greater levels of psychological distress in female cancer patients than in men, associated with a higher incidence of depression, hopelessness and anxiety, which in turn negatively affect perceptions of quality of life. It is hypothesized that for women, the emotional burden is compounded by the sense of responsibility they feel for the impact of treatment and hospitalization on the management of their children and family.

Now that the negative impact of cancer has been widely documented, it is also interesting to analyze the psychological resources that may play a protective role in counteracting the impact of psychological distress on quality of life in cancer patients, as shown in previous studies.

In our study, quality of life appears to be correlated with levels of resilience, but not with perceived social support. In addition, the mediation model highlights a mediating role of resilience in counteracting the negative effects of age, gender and depression on QoL (Fig. 1).

Previously, Ristevska-Dimitrovska et al.70 conducted a study with 218 consecutive breast cancer patients and found that overall quality of life was positively correlated with resilience levels. Specifically, all functional quality of life scales (physical, role, emotional, cognitive and social functioning) correlated positively to resilience, while symptom severity correlated negatively. The study also found that patients with higher levels of resilience had fewer symptoms of depression, confirming that resilience is a protective factor against depression and distress. Less resilient breast cancer patients reported poorer body image, were more pessimistic about their future prospects, and suffered more severe side effects from the treatments and therapies they received.

Wu et al.71 also tested a mediation model on a sample of 40 adolescent cancer patients and found that distress symptoms had a negative impact on quality of life, but that resilience levels played a role in buffering the negative impact of symptoms.

Focusing on hematology patients, other research had already highlighted63 how hematological malignancies such as leukemia, lymphoma and myeloma usually involve complex and long-term treatment processes that pose considerable psychological and emotional challenges for patients and their families. Therefore, psychological resilience plays a crucial role in the study of patients with hematological malignancies, affecting not only their mental health but also treatment outcomes and quality of life. For example, Tian and Wang63 recently conducted a study of 100 patients with hematological malignancies to assess the relationship between patient characteristics (age, gender, education level), fear of progression, resilience and sleep quality, a key aspect in patients’ lives as it is closely related to mood and depression levels. The results suggest that fear of progression has a negative impact on sleep quality, but resilience plays a mediating role in mitigating its effects.

Contrary to expectations, we did not find a protective effect of social support on quality of life. However, this finding is consistent with previous studies that have found conflicting evidence in this regard.

For example, Lewandowska et al.57 found a high percentage of patients who reported that the disease had brought them closer to family and friends. The authors therefore suggested that an extremely important aspect of cancer patients’ quality of life was the impact of the disease on their marital, family and social relationships and the support they received.

Their study found that for 37% of respondents, relationships with family and friends had not been altered by the disease and remained satisfactory, while for 28% of patients, relationships with partners had actually improved.

Similarly, Gangane et al.72 conducted a study of 208 female patients with infiltrating breast cancer and found that partner absence was negatively correlated with quality of life, mental health and social relationships.

In a study of cancer patients, Rodriguez et al.73 found that social support, resilience and optimism were positively correlated with quality of life. Support from friends was the variable that most improved patients’ overall health, while support from partners was the variable that best improved patients’ coping with the disease. Similarly, emotional support from a partner, together with support from family, were the variables that most helped to reduce patients’ symptoms. The research showed that both resilience and optimism improved overall health and functioning and reduced symptoms. Like our study, Rodriguez et al.73 also found gender differences, with women having a lower quality of life than men, particularly in the way they coped with cancer.

However, findings on the role of social support are inconsistent: for example, Jacob et al.74 found that unmarried patients reported higher social/family well-being than married patients, and married women reported lower social/family well-being than unmarried women.

In conclusion, this work has highlighted the importance of quality of life in hematology patients and the mediating role of resilience in counteracting the effects of variables such as age, gender and depression.

However, there are some limitations to this study: the sample size was relatively small, which may affect the generalizability of the results. Future studies with larger and more diverse samples may provide more robust results. Secondly, self-report questionnaires were used to measure the variables studied, which limits the measures to patients’ perceptions of their level of depression, PTSD, resilience or quality of life. This approach introduces the possibility of response bias, and the lack of objective measures limits the accuracy of the assessments. The inclusion of clinical interviews or other objective methods in future research may provide a more comprehensive understanding of these psychological variables.

The cross-sectional design of this study provides a snapshot of the relationships between psychological outcomes, resources and quality of life. However, it does not allow for the exploration of causal relationships or how these variables interact over time. Longitudinal studies could provide deeper insights into the dynamic processes involved.

A further limitation consists in not having taken into consideration aspects of the illness, as the stage, the time since diagnosis and the severity of cancer that could impact on quality of life of the patient. This limit is mitigated by the fact that there was a certain homogeneity in the sample due to the inclusion criteria which required a diagnosis for at least three months and a life expectancy of at least six months, but a specific analysis of the role played by the duration and severity of illness could lead to more effective results.

Finally, resilience and quality of life are complex, multifaceted constructs that may not be adequately captured by quantitative questionnaires alone. The inclusion of qualitative interviews in future studies could enrich the findings by capturing patients’ personal experiences and coping strategies.

Despite these limitations, the study provides useful guidance for clinical practice, suggesting that clinicians pay attention not only to the physical condition but also to the psychological state of patients and help them to develop an optimistic and self-reinforcing attitude and reduce negative psychological problems. In addition, he suggests implementing personalized intervention plans tailored to the specific needs of patients to improve psychological resilience more effectively.

Conclusion

The present study highlights the significant impact of haematological cancer on patients’ mental health and quality of life. The results show that depression, PTSD and low resilience are prevalent in these patients, particularly in older individuals and women. Resilience emerged as an important protective factor, mediating the negative effects of age, gender and depression on quality of life. Although social support did not have a significant effect, these findings highlight the importance of psychological resilience in improving patient outcomes.

The importance of this study highlights the need for healthcare professionals to consider not only physical treatment, but also the psychological well-being of hematologists. Future research should explore more comprehensive and individualized interventions aimed at strengthening resilience. In addition, the use of more qualitative assessments could provide a deeper understanding of the complex factors that influence patients’ quality of life. Such findings can guide the development of tailored psychological support programs that improve overall patient care.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors (write to: Cristina Liviana Caldiroli, e-mail: cristina.caldiroli@unimib.it), without undue reservation.

References

WHOQOL Group. What quality of life? The WHOQOL group. World Health Forum 17, 354–356 (1996).

WHOQOL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol. Med. 28(3), 551–558. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291798006667 (1998).

Frisch, M. B. Quality of life therapy and assessment in health care. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 5(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.1998.tb00132.x (1998).

Movsas, B. Quality of life in oncology trials: A clinical guide. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 13(3), 235–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-4296(03)00029-8 (2003).

Leplège, A. & Hunt, S. The problem of quality of life in medicine. JAMA 278(1), 47–50. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1997.03550010061041 (1997).

Balestroni, G. & Bertolotti, G. L. EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D): Uno strumento per la misura della qualità della vita. Monaldi Arch. Chest Dis. 78(3), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.4081/monaldi.2012.121 (2012).

Coons, S. J., Rao, S., Keininger, D. L. & Hays, R. D. A comparative review of generic quality-of-life instruments. Pharmacoeconomics 17, 13–35. https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200017010-00002 (2000).

Labbrozzi D. Misure di salute e di vita: introduzione ai metodi ed agli strumenti per la valutazione dello stato di salute e della qualità della vita nella ricerca e nella pratica clinica. Il Pensiero Scientifico (1995).

Majani, G. Introduzione alla Psicologia della Salute 103–114 (Edizioni Erickson, 1999).

Detmar, S. B., Aaronson, N. K., Wever, L. D., Muller, M. & Schornagel, J. How are you feeling? Who wants to know? Patients’ and oncologists’ preferences for discussing health-related quality-of-life issues. J. Clin. Oncol. 18(18), 3295–3301. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2000.18.18.3295 (2000).

Slevin, M. L. et al. Attitudes to chemotherapy: Comparing views of patients with cancer with those of doctors, nurses, and general public. BMJ 300(6737), 1458–1460. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.300.6737.1458 (1990).

Olsen, C. D. H., Möller, S. & Juel, A. L. Sex differences in quality of life and depressive symptoms among middle-aged and elderly Europeans: Results from the SHARE survey. Aging Ment. Health. 27(1), 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.2013434 (2023).

Girgus, J. S., Yang, K. & Ferri, C. V. The gender difference in depression: Are elderly women at greater risk for depression than elderly men? Geriatrics 2(4), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics2040035 (2017).

Austad, S. N. & Fischer, K. E. Sex differences in lifespan. Cell Metab. 23(6), 1022–1033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.019 (2016).

Ganz, P. A., Bernhard, J. & Hurny, C. Quality of life and psychosocial oncology research in Europe: State of the art. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 9, 1–22 (1991).

Osoba, D. The quality of life committee of the clinical trials group of the National Cancer Institute of Canada: Organization and functions. Qual. Life Res. 1, 211–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00635620 (1992).

Epstein, R. M. et al. Effect of a patient-centered communication intervention on oncologist-patient communication, quality of life, and health care utilization in advanced cancer: The VOICE randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 3(1), 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4373 (2017).

Korfage, I. J. et al. Five-year follow-up of health-related quality of life after primary treatment of localized prostate cancer. Int. J. Cancer 116(2), 291–296. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.21043 (2005).

Mandelblatt, J. S. et al. Predictors of long-term outcomes in older breast cancer survivors: Perceptions versus patterns of care. J. Clin. Oncol. 21(5), 855–863. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2003.05.007 (2003).

Harrington, C. B., Hansen, J. A., Moskowitz, M., Todd, B. L. & Feuerstein, M. It’s not over when it’s over: Long-term symptoms in cancer survivors—A systematic review. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 40(2), 163–181. https://doi.org/10.2190/PM.40.2.c (2010).

Firkins, J., Hansen, L., Driessnack, M. & Dieckmann, N. Quality of life in “chronic” cancer survivors: A meta-analysis. J. Cancer Surviv. 14, 504–517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00869-9 (2020).

Lee, S. J. et al. Routine screening for psychosocial distress following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 35(1), 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1704709 (2005).

Menoni, E. & Ridolfi, A. Distress, coping and quality of life in patients who underwent a bone marrow transplantation. Riv. Psicol. Clin. 2, 205 (2008).

Schulz-Kindermann, F., Hennings, U., Ramm, G., Zander, A. R. & Hasenbring, M. The role of biomedical and psychosocial factors for the prediction of pain and distress in patients undergoing high-dose therapy and BMT/PBSCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 29(4), 341–351. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1703385 (2002).

Stein, K. D., Syrjala, K. L. & Andrykowski, M. A. Physical and psychological long-term and late effects of cancer. Cancer 112(S11), 2577–2592. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23448 (2008).

Mokhatri-Hesari, P. & Montazeri, A. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: Review of reviews from 2008 to 2018. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 18, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01591-x (2020).

Ahmed, E. Antidepressants in patients with advanced cancer: When they’re warranted and how to choose therapy. Oncology 33(2), 62 (2019).

Koenig, H. G., Cohen, H. J., Blazer, D. G., Meador, K. G. & Westlund, R. A brief depression scale for use in the medically ill. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 22(2), 183–195. https://doi.org/10.2190/M1F5-F40P-C4KD-YPA3 (1992).

McDermott, C. L., Bansal, A., Ramsey, S. D., Lyman, G. H. & Sullivan, S. D. Depression and health care utilization at end of life among older adults with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 56(5), 699–708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.08.004 (2018).

Spiegel, D., Kraemer, H., Bloom, J. & Gottheil, E. Effect of psychosocial treatment on survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Lancet 334(8668), 888–891. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(89)91551-1 (1989).

Spiegel, D. et al. Effects of supportive-expressive group therapy on survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer: A randomized prospective trial. Cancer 110(5), 1130–1138. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.22890 (2007).

Walker, J. et al. Prevalence of depression in adults with cancer: A systematic review. Ann. Oncol. 24(4), 895–900. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mds575 (2013).

Caruso, R. et al. Depressive spectrum disorders in cancer: Prevalence, risk factors and screening for depression: A critical review. Acta Oncol. 56(2), 146–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2016.1266090 (2017).

Crotti, N., Di Leo, S., & Viterbori, P. (eds.) Dalla paura al cambiamento. In: Cancro: percorsi di cura 41–55 (1998).

Morasso, G., & Di Leo, S. La psico-oncologia: Un panorama generale. Nuove prospettive in Psico-oncologia 46 (2002).

Bellani, M. et al. Psiconcologia—Il Trattato Italiano (Masson Editore, 2002).

Alexander, S., Minton, O. & Stone, P. C. Evaluation of screening instruments for cancer-related fatigue syndrome in breast cancer survivors. J. Clin. Oncol. 27(8), 1197–1201. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.19.1668 (2009).

Marziliano, A., Tuman, M. & Moyer, A. The relationship between post-traumatic stress and post-traumatic growth in cancer patients and survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psycho-Oncology 29(4), 604–616. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5314 (2020).

Castiglioni, M. et al. The up-side of the COVID-19 pandemic: Are core belief violation and meaning making associated with post-traumatic growth? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20(11), 5991. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115991 (2023).

Rutter, M. Implications of resilience concepts for scientific understanding. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1094(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1376.002 (2006).

Calhoun, L. G. & Tedeschi, R. G. Facilitating Posttraumatic Growth: A Clinician’s Guide (Routledge, 1999).

Tedeschi, R. G. & Calhoun, L. G. Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol. Inq. 15(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01 (2004).

Castiglioni, M., Caldiroli, C. L., Manzoni, G. M. & Procaccia, R. Does resilience mediate the association between mental health symptoms and linguistic markers of trauma processing? Analyzing the narratives of women survivors of intimate partner violence. Front. Psychol. 14, 1211022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1211022 (2023).

Aspinwall, L. G. The psychology of future-oriented thinking: From achievement to proactive coping, adaptation, and aging. Motiv. Emot. 29, 203–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-006-9013-1 (2005).

Costantino, M. A. & Camuffo, M. Trasformazioni del concetto di resilienza e ricadute nella pratica. Ric. Prat. (Istituto Mario Negri) 25, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1707/423.5029 (2009).

Grassi, L. et al. Screening for distress in cancer patients—A multi-center, nationwide study in Italy. Cancer 119, 1714–1721. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.27902 (2013).

Grassi, L. et al. Educational intervention in cancer outpatient clinics on routine screening for emotional distress: An observational study. Psycho-Oncology 20(6), 669–674 (2011).

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A. & Brown, G. Beck depression inventory-II. Psychol. Assess. 1, 210 (1996).

Ghisi, M., & Sanavio, E. Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition. Adattamento Italiano: Manuale. Firenze: O-S Organizzazioni Speciali (2006).

King, L. A., King, D. W., Leskin, G. A. & Foy, D. W. The Los Angeles symptom checklist: A self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder. Assessment 2(1), 1–17 (1995).

Friborg, O., Hjemdal, O., Rosenvinge, J. H. & Martinussen, M. A new rating scale for adult resilience: What are the central protective resources behind healthy adjustment? Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 12(2), 65–76 (2003).

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G. & Farley, G. K. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J. Pers. Assess. 52(1), 30–41 (1988).

Prezza, M. & Principato, M. C. La rete sociale e il sostegno sociale. In Conoscere la Comunità (eds Prezza, M. & Santinello, M.) (Il Mulino, 2002).

Brooks, R. et al. EQ-5D in selected countries around the world. In The Measurement and Valuation of Health Status Using EQ-5D: A European Perspective: Evidence from the EuroQol BIOMED Research Programme 207–227 (Springer, 2003).

Baron, R. M. & Kenny, D. A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51(6), 1173 (1986).

Ho, P. J., Gernaat, A. M., Hartman, M. & Verkooijen, H. M. Health-related quality of life in Asian patients with breast cancer: A systematic review. BMJ Open 8(4), e020512. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020512 (2018).

Lewandowska, A. et al. Quality of life of cancer patients treated with chemotherapy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 6938. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17196938 (2020).

Annunziata, M. A. et al. Long-term quality of life profile in oncology: A comparison between cancer survivors and the general population. Support Care Cancer 26, 651–656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3880-8 (2018).

Pekała, M. & Kozaka, J. Quality of life of lung cancer patients. Psychoonkologia 20, 90–97. https://doi.org/10.5114/pson.2016.62058 (2016).

Montazeri, A., Milroy, R., Hole, D., McEwen, J. & Gillis, C. R. Quality of life in lung cancer patients: As an important prognostic factor. Lung Cancer 31, 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-5002(00)00179-3 (2001).

Li, T. C. et al. Quality of life predicts survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Public Health 12, 790. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-790 (2012).

Herrero-Sánchez, M. D., García-Iñigo, C., Nuño-Beato-Redondo, B. S., Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C. & Alburquerque-Sendín, F. Association between ongoing pain intensity, health-related quality of life, disability and quality of sleep in elderly people with total knee arthroplasty. Cien Saude Colet. 19, 1881–1888. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232014196.04632013 (2014).

Tian, Y. & Wang, Y. L. Resilience provides mediating effect of resilience between fear of progression and sleep quality in patients with hematological malignancies. World J Psychiatry 14(4), 541–552. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i4.541 (2024).

Amir, M. & Ramati, A. Post-traumatic symptoms, emotional distress and quality of life in long-term survivors of breast cancer: A preliminary research. J. Anxiety Disord. 16, 195–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00095-6 (2002).

Gold, J. I. et al. The relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder, mood states, functional status, and quality of life in oncology outpatients. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 44(4), 520–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.10.014 (2012).

Dehkordi, A., Heydarnejad, M. S. & Fatehi, D. Quality of life in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Oman Med. J. 24, 204–207. https://doi.org/10.5001/omj.2009.40 (2009).

Nayak, M. G. et al. Quality of life among cancer patients. Indian J. Palliat. Care 23, 445–450. https://doi.org/10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_82_17 (2017).

Geffen, D. B., Blaustein, A., Amir, M. C. & Cohen, Y. Post-traumatic stress disorder and quality of life in long-term survivors of Hodgkin’s disease and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in Israel. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 44, 1925–1929. https://doi.org/10.1080/1042819031000123573 (2003).

Modlińska, A. et al. Influence of the molecular structure of thermotropic liquid crystals on their ability to form monolayers at interface. Liq. Cryst. 36(2), 197–208 (2009).

Ristevska-Dimitrovska, G., Filov, I., Rajchanovska, D., Stefanovski, P. & Dejanova, B. Resilience and quality of life in breast cancer patients. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 3(4), 727–731. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2015.128 (2015).

Wu, W. W. et al. The mediating role of resilience on quality of life and cancer symptom distress in adolescent patients with cancer. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 32(5), 304–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043454214563758 (2015).

Gangane, N., Khairkar, P., Hurtig, A. K. & San, S. M. Quality of life determinants in breast cancer patients in central rural India. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 18, 3325–3332. https://doi.org/10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.12.3325 (2017).

Rodriguez-Gonzalez, A. et al. Fatigue, emotional distress, and illness uncertainty in patients with metastatic cancer: Results from the prospective NEOETIC_SEOM study. Curr. Oncol. 29(12), 9722–9732 (2022).

Jacob, J. et al. Health-related quality of life and its socio-economic and cultural predictors among advanced cancer patients: Evidence from the APPROACH cross-sectional survey in Hyderabad-India. BMC Palliat. Care. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-019-0465-y (2019).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.P. and C.L.C. contributed to the conception of the research; R.P., C.L.C., M.C. worked on the design of the work; R.P., C.L.C., M.C., S.S. worked on the acquisition and analysis of the data; R.P., C.L.C., S.S., M.T. contributed to the interpretation of the data; R.P, C.P., C.L.C., S.S. drafted the first version of the work; R.P., C.L.C., S.S., M.C., M.T., D.D. contributed to the final version of the work; R.P., C.L.C., S.S., M.C., M.T., D.D. substantially revised the final article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Ethics Committee of eCampus University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Caldiroli, C.L., Sarandacchi, S., Tomasuolo, M. et al. Resilience as a mediator of quality of life in cancer patients in healthcare services. Sci Rep 15, 8599 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93008-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93008-2