Abstract

Thrombocytopenia is a common hematologic concern in neonates and can lead to severe complications, including significant bleeding particularly intracranial hemorrhage. This risk is especially critical in preterm infants or those with other coexisting conditions. While neonatal thrombocytopenia has been studied in some countries, there is limited data and understanding about its prevalence, and associated factors in resource-limited countries especially in Ethiopia. So this study aimed to assess the prevalence and factors associated with thrombocytopenia among neonates admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit of Northwest Amhara Region Comprehensive Specialized Hospitals in Northwest Ethiopia, 2022. Institution-based cross-sectional study design was conducted from October 05 to November 03, 2022, and a systematic random sampling technique was used to select 423 study participants. Data were collected by interviewing mothers and reviewing neonates’ medical records. Data were entered into Epi-Data version 4.6.0 and exported to STATA version 14 for analysis. Both bivariable and multivariable logistic regression models were used for analysis. P-value of less than 0.05 and odds ratio with 95% CI was used to declare the presence of association. A total of 415 neonate-mother pairs were involved with a response rate of 98.1%. The prevalence of thrombocytopenia among neonates admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit Is found to be 26.02%; [95% CI (22.01–30.48%)]. In the multivariable analysis severe pre-eclampsia (AOR = 2.84 95% CI 1.29–6.27), prolonged rupture of membrane (AOR = 2.85 95% CI 1.21–6.72), neonatal sepsis (AOR = 6.50 95% CI 3.58–11.79), perinatal asphyxia (AOR = 4.15 95% CI 1.97–8.76), and necrotizing enterocolitis (AOR = 3.71 95% CI 1.68–8.19) were significant factors to thrombocytopenia. To decrease the occurrence of neonatal thrombocytopenia better to give special attention and priority to neonates diagnosed with sepsis, perinatal asphyxia, necrotizing enterocolitis, and mothers who had prolonged rupture of membrane or severe pre-eclampsia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Neonatal thrombocytopenia (NT) is defined as a platelet count below the lower limit of the normal range, although clinically dangerous bleeding is not seen until counts drop well below 50, 000 per microliter1,2. It is classified into two based on the onset of time to early-onset thrombocytopenia (occurs within 72 h after birth) and late-onset thrombocytopenia (occurs after 72 h of birth)3,4,5.

Studies showed that the prevalence of NT was 14% in the Balkans6, and 24–68.4% in Pakistan7,8. In Africa, the magnitude of NT ranged from 12.4 to 53%7,9,10,11 whereas, in Ethiopia, its prevalence in preterm neonates with early onset sepsis was 48.5%12. It is among the most common hematological problems observed in neonates admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), particularly affecting sick newborns and preterm infants during the neonatal period1,13.

Studies conducted in South Asia showed that 12.6-14.5% of neonates died from thrombocytopenia and 9-28.2% developed intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH)6,14,15,16. Several studies show that IVH is the most serious complication and is more common in infants with NT (10–20%), especially for extremely low birth weight neonates or preterm neonates2,3,17. Neonates with thrombocytopenia are also more likely to experience various types of abnormal bleeding, such as gastrointestinal, pulmonary, and cutaneous bleeding2,17. Despite the government’s priority issue of reducing neonatal mortality, it has increased from 29 to 33 per 1000 live births from 2016 to 201918,19. Meanwhile, NT is recognized as one of the significant contributors to neonatal morbidity and mortality. A systematic review and meta-analysis studies revealed that thrombocytopenia is one of the causes of failure of ductus arteriosus to spontaneously close in preterm newborns, which resulted in neonatal morbidity and mortality20,21.

The development of thrombocytopenia in the intensive care unit typically signifies the complication of the co-morbidities process and needs prolonged hospitalization for recuperation. In addition, it requests high cost that leads to economic burdens on the family, society, and health care systems. To alleviate the problem and increase the survival of neonates, the world health organization (WHO) recommends the ministry of health to expand the quality of services for neonates by strengthening newborn care and maternal obstetric health programs9,22,23.

Various studies suggest that small for gestational age (SGA), pregnancy-induced hypertension, prematurity, perinatal asphyxia (PNA), sepsis, polycythemia, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), and placental insufficiency were factors significantly associated with early-onset thrombocytopenia whereas late-onset thrombocytopenia is typically greater and frequently secondary to neonatal sepsis or necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC)2,4,24,25.

Despite NT being so common, little attention is given to the assumption that it has resolved spontaneously even though having significant health problems. However, if it is not identified early and treated effectively, it might cause fatal consequences or internal bleeding5,26,27. Despite this, there is limited information that shows the prevalence and factors significant with NT in Ethiopia. Therefore, determining the prevalence and its associated factors can be used as a piece of evidence for the concerned stakeholders to address the problem and the potential factors for neonatal thrombocytopenia.

Methods and materials

Study design, period, and area

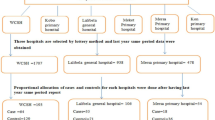

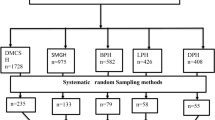

A multicenter institution-based cross-sectional study design was conducted from October 05 to November 03, 2022, in Northwest Amhara regional State comprehensive specialized hospitals. The study was conducted in five Comprehensive Specialized Hospitals (University of Gondar, Felege-Hiwot, Tibebe Ghion, Debre Tabor, and Debre-Markos). Those hospitals have special units; like NICU, and the major services in NICU include general neonatal care services, routine prescription of complete blood count, blood exchange transfusion, phototherapy, and ventilation support. The average annual admission of neonates was 4,560 (2,562 inborn) at University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, 1,836 (1,003 inborn) at Felege Hiwot Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, 1,920 (1,085 inborn) at Tibebe Ghion Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, 1,560 (847 inborn) at Debre Tabor Comprehensive Specialized Hospital and 1,692 (953 inborn) at Debre Markos Comprehensive Specialized Hospital.

Population

The source populations were all mothers with their neonates that were admitted to the NICU of Northwest Amhara region comprehensive specialized hospitals, and the study populations were all neonate-mother pairs in the study area during the study period. Neonates who had no platelet count as part of their lab investigation and mothers who were critically ill or treated in other wards/ intensive care units were excluded.

Sample size determination, sampling procedure, and study variables

The sample size was calculated using the single population proportion formula by considering an assumption Zα/2 = 1.96, proportion was considered to be 50%, and d = the margin error between the sample and the population, which is 5%.

By adding a 10% non-response rate the final sample size became 423. The study was conducted in the Northwest Amhara region’s five comprehensive specialized hospitals. The average baseline data at one-year admission data were taken from each hospital to consider the available data. Then allocation of the sample size to each hospital was made based on the average number of neonate admission per month. The overall sample was taken proportionally from each hospital and a systematic random sampling technique (sampling interval ≈ 3) was used to select the sample participants. The first participant was selected randomly by manually lottery method at the beginning of the data collection time.

Variables of the study

Dependent variable

Neonatal thrombocytopenia (Yes/No).

Independent variables

Socio-demographic characteristics of the mother and the neonate

Maternal age, residence, educational status, marital status, occupational status, and sex of the baby.

Maternal obstetric-related variables

Parity, antenatal care (ANC) follow-up, place of delivery, mode of delivery, hepatitis B virus infection, SPE, eclampsia, GDM, antepartum hemorrhage (APH), premature rupture of membranes (ROM) and prolonged ROM.

Neonatal-related variables

Gestational age, birth weight, number of index pregnancy, weight for gestational age and prolonged not feeding orally (NPO).

Neonatal clinical co-morbidity variables

Sepsis, NEC, PNA, jaundice, neonatal surgical management, polycythemia, meconium aspiration syndrome (MAS), respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), and anemia.

Operational definition

Thrombocytopenia: A platelet count of less than 150,000 per microliter of blood regardless of the gestational age28.

Prolonged NPO: A neonate who is NPO for greater than 24 h29.

Prolonged ROM: Rupture of membrane more than 18 h30.

Low birth weight: An infant born weighing a birth of less than 2500 g31.

Prematurity: A neonate is born before 37 weeks of pregnancy have been completed32.

Premature ROM: a rupture of membranes before labor starts30.

Neonatal surgical management: Neonates who had surgical management for tracheoesophageal fistula or gastroschisis or omphalocele or anorectal malformations33.

Data collection tool, procedure and quality control

The data collection tool was adapted by reviewing related kinds of literature and adopted from validated standards like the Ethiopian demographic health survey checklists. It was prepared in English and translated into the Amharic language, then retranslated to English by language experts and health professionals to check for consistency and flow, while for clinical variables (chart review checklists) English version was developed. Before starting data collection, the tool was evaluated and commented on by a research expert for its validity. After verbal and written informed consent was obtained from the mothers, data were collected by interviewing mothers and reviewing neonates’ medical records. Three supervisors: Sr. Tigst Asres (BSc neonatal nurse), Mr. Awugichew Esubalew (BSc neonatal nurse) and Mrs. Rahel Asres (MSc pediatrics nurse) and data collectors: Mr. Molla Asfaw (BSc neonatal nurse), Asnakew Tigabu (BSc neonatal nurse), and Mr. Misganew Tesfaye (BSc neonatal nurse) were involved in the data collection process. A 5% pretest was conducted at the Woldiya Comprehensive Specialized Hospital before the actual data collection for the validity of the instrument or questionnaire.

Data processing and analysis

Data were checked, coded, and entered into Epi-Data version 4.2.0 and exported to STATA version 14 for analysis. The outcome variable was dichotomized and coded as 0 and 1, representing those who are not thrombocytopenic and thrombocytopenic respectively. Pearson rank chi-square assumption fulfillment was checked for categorical variables. A bivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to find the association of each independent variable with the outcome variables. All variables with a significant association in the bivariable logistic regression analysis (p < 0.2) were entered into the final multivariable logistic regression analysis to control confounders and identify the independent effects of different factors on the occurrence of thrombocytopenia. Adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated, and a p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The goodness of model fitness was tested by the Hosmer and Lemeshow test and the model were adequate. The variance inflation factor was used to test multicollinearity (VIF = 1.41).

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval (Ref. No. 035/2022) was obtained from the ethical review committee of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Gondar for the Amhara Public Health Institute. A formal letter of permission was obtained from the Amhara Public Health Institute for each hospital. Finally, written consent was obtained from the mothers after a thorough explanation of purposes, benefits, information confidentiality, and the voluntary nature of participation. All methods were performed in accordance with the declarations of Helsinki and relevant guidelines and regulations. The names and/or identification numbers of the study participants were not recorded on the data collection tool. All information was kept completely private and utilized exclusively for the objectives of this study.

Result

Socio-demographic and behavioral characteristics

A total of 415 neonate-mother pairs were included in the study with a response rate of 98.1%. The mean age of the mothers was 26.8 (± 5.1 SD) years ranging from 18 to 40 years, and most (86.5%) mothers belonged to the age groups of 20–35 years. Regarding the occupational status of the mothers, nearly 44% of mothers were housewives, and more than half of neonates (57.1%) were females (Table 1).

Maternal obstetric history

Most (98.6%) mothers attended ANC follow-up for the index pregnancy, and out of those, 55.3% had four and above visits. Most (91.8%) mothers delivered at health institutions, and more than half (58.3%) of mothers gave birth via spontaneous vaginal delivery (SVD) (Table 2).

Maternal obstetric complications

This study finding revealed that 12.1% of mothers had experienced SPE. In addition, 13.0% of mothers had premature ROM and 9.4% of mothers had prolonged ROM (Table 3).

Neonatal-related factors

Out of the total newborn babies, more than two-thirds (68.7%) of neonates were born at term, and 67.2% of neonates had a birth weight of 2500 g and above. The mean age and weight of neonates at the time of birth were 37.6 (± 2.6 SD) weeks and 2717.6 (± 841.8 SD) grams, respectively (Table 4).

Neonatal clinical co-morbidities

Neonatal clinical co-morbidities during admission were reviewed from the medical record of the neonates. Out of 415 reviewed charts, neonates admitted to NICU regarding co-morbidities more than one-third of the neonates (36.9%) had sepsis, 22.4% had jaundice, and 20% had MAS (Table 5).

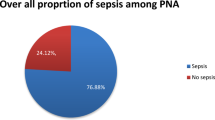

Prevalence of neonatal thrombocytopenia

The prevalence of thrombocytopenia among neonates admitted to the NICU of Northwest Amhara region comprehensive specialized hospitals was found to be 26.02% with 95% CI (22.01, 30.48%).

Factors associated with neonatal thrombocytopenia

From the multivariable logistic regression analysis SPE, prolonged ROM, neonatal sepsis, PNA, and NEC were statistically significant with neonatal thrombocytopenia.

Neonates born from SPE mothers were 2.8 times more likely to have thrombocytopenia as compared to neonates born from normotensive mothers [(AOR: 2.84, 95% CI (1.29 6.27)]. Similarly, neonates born from a mother who had prolonged ROM were approximately 3 times more likely to develop thrombocytopenia than those delivered from a mother who had not prolonged ROM diagnosed [(AOR: 2.85, 95% CI (1.21 6.72]. The odds of thrombocytopenia were 6.5 times higher among neonates who had sepsis as compared to their counterparts [AOR: 6.50; 95%CI (3.58, 11.79)]. The neonates with PNA were approximately 4.2 times more likely to have thrombocytopenia, as compared to those neonates who had not PNA diagnosed [AOR: 4.15; 95%CI (1.97 8.76)]. In the same way, the odds of thrombocytopenia were 3.7 times more in neonates who had NEC than those neonates who had no NEC diagnosed [AOR: 3.71, 95% CI (1.68 8.19)]. (Table 6)

Discussion

In this study, the prevalence of neonatal thrombocytopenia was 26.02% [95% CI (22.01%, 30.48%)], which was in line with previous studies conducted in Pakistan (24%)8, India (25.45% and 29%)2,4, and Iran (28.5%)34.

However, this result was higher than the findings from Tunisia (12.4%)35, South Africa (15.6%)11, and Nepal (18%)5. The discrepancy might be due to the difference in the study settings like the quality of NICU, which meant infection prevention practice differences in hospitals. In Ethiopia hospitals, the infection prevention practice was 52.2%36 whereas in Nepal was 76.2%37. Additionally, the possible justification might be being a single-centric study while the current study is multi-institutional-based.

On the other hand, this study also had a lower prevalence than other studies carried out in Ethiopia (48.5%)38, Egypt (38.18%)39, Nigeria (53%)40, India (36.1%)41, and Pakistan (68.24%)42. This variation might be due to the study population differences between the previous Ethiopia study, which focused only on preterm neonates with sepsis38, the Indian study, which focused solely on neonates born from pregnancy-induced hypertension41, and the Pakistan study, which focused exclusively on neonatal sepsis42 whereas all neonates, regardless of gestational age, were used in the current study. Another possible justification may be the sample size they used is much lower than the current study39,40.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that SPE, prolonged ROM, neonatal sepsis, PNA, and NEC were factors significantly associated with NT.

The present study identified that the odds of having thrombocytopenia among neonates who were delivered to SPE mothers were 2.8 times higher compared with those neonates who were delivered from normotensive mothers. This finding was supported by studies from Egypt39, Nepal5, Iran34, India43, and South Asia8. This might be because preeclampsia is a multi-system disorder associated with adaptive changes in the fetal circulation and causes a marked imbalance in the haemostatic system of the mother and the neonate end up with thrombocytopenia. Since SPE causes placental insufficiency results in a direct depressant effect on fetal megakaryocytopoiesis, which is the cellular developmental process before the release of platelets into the circulation. On the other hand, it also causes maternal low platelet which gives rise to antibodies against her platelets resulting in passive transmission of those antibodies from mother to fetus through the placenta and attacking the fetus platelet end up with thrombocytopenia25,44. Additionally, chronic exposure to increased levels of erythropoietin in the fetus due to fetal hypoxia secondary to preeclampsia may also lead to thrombocytopenia by suppressing the megakaryocytic cell line which may lead to decreased platelet production45.

The odds of thrombocytopenia were approximately 3 times higher among neonates who were born to mothers diagnosed with prolonged ROM compared with those neonates born to mothers who had no prolonged ROM. This finding was supported by finding in the United Kingdom46. It might be because a woman with prolonged rupture of membranes is at risk of intra-amniotic infection (perinatal infection), which is considered one of the most conditions for early-onset neonatal thrombocytopenia25. The activation of reticuloendothelial cells and subsequent platelet removal are caused by injury to endothelial cells, which is the most likely cause of platelet count reduction47 .

According to the current study, neonates with sepsis were 6.5 times more likely to be thrombocytopenic as compared to neonates without sepsis, which was in line with studies in Ethiopia38,48, Egypt39,49, Nigeria40, Tunisia50, Nepal5, South Asia15, and UK27. Due to the fact that sepsis increases the risk of thrombocytopenia by destruction and the consumption of platelet results in thrombocytopenia. Since thrombocytopenia is a common and multifactorial phenomenon occurring during sepsis3,25. The other possible reason is that bacteria may cause endothelial damage leading to platelet adhesion and aggregation or may bind directly to platelets leading to aggregation and accelerated clearance from circulation and it is also a highly specific marker of fungal sepsis42,51. In addition, the possible justification may be that sepsis-induced thrombocytopenia is caused by a decrease in platelet synthesis in the bone marrow52.

Those neonates who had PNA had approximately 4.2 times higher odds for thrombocytopenia when compared with neonates without PNA. This is consistent with other studies carried out in Nigeria40, Nepal5, Iran34, India43, South Asia15, and Europe13. It might be because PNA decreases platelet production and it is considered one of the most common causes of early-onset thrombocytopenia. Moreover, PNA is also associated with disseminated intravascular coagulation, which may cause platelet activation and consumption25,53. Additionally, neonates who suffer from issues like perinatal asphyxia can become seriously sick and develop thrombocytopenia as a result of platelet consumption from a complication54.

Neonates who had NEC had 3.7 times higher odds for thrombocytopenia than neonates without NEC diagnosed. This is supported by studies carried out in the USA55, and Europe13. Fifty to ninety-five% of all neonates with NEC develop thrombocytopenia within 24–72 h and the primary mechanism for thrombocytopenia is widely believed to be increased platelet destruction in the endothelium of vessels that supply blood to areas of the bowel in the early stages of necrosis56,57. In addition, the possible justification may be because of the following two reasons: the first one is due to stimulation of endothelial cells and macrophages to release inflammatory cytokines, which, along with thromboplastin released from gangrenous bowel, can increase platelet activation and aggregation in the microvasculature56 and the second one is elevated thrombopoietic response is due to increased levels of platelet factor 4, which is released from activated platelets and is a potent inhibitor of megakaryocytopoiesis58.

This study has some limitations that should be considered. The cross-sectional nature of the study did not tell the temporal relationship among variables. Data lacks maternal medication and TORCH infection history that may affect NT, because of not recorded in the neonatal medical chart.

Conclusions

The main obstetric complications of mothers of neonatal admission in the study area were premature ROM followed by SPE, and the majority of neonates were born at term. The prevalence of neonatal thrombocytopenia among neonates admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit was found to be high. SPE, prolonged ROM, neonatal sepsis, PNA, and NEC were factors significantly associated with the prevalence of neonatal thrombocytopenia. To minimize the burden of neonatal thrombocytopenia, particular interest should be given to neonates diagnosed with sepsis, PNA, NEC, and mothers who had prolonged ROM or SPE. Future researchers will better do longitudinal research that can identify the temporal relationship to make the inference.

List of Tables.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available due to confidentiality issues. But data will be available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- AGA:

-

Appropriate for gestational age

- ANC:

-

Antenatal care

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odd ratio

- APH:

-

Antepartum hemorrhage

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COR:

-

Crude odd ratio

- GDM:

-

Gestational diabetes mellitus

- HBsAg:

-

Hepatitis B virus surface antigen

- ICH:

-

Intracranial hemorrhage

- IVH:

-

Intraventricular hemorrhage

- LBW:

-

Low birth weight

- LGA:

-

Large for gestational age

- MAS:

-

Meconium aspiration syndrome

- NEC:

-

Necrotizing enterocolitis

- NICU:

-

Neonatal intensive care unit

- NPO:

-

Not per oral

- NT:

-

Neonatal thrombocytopenia

- PNA:

-

Perinatal asphyxia

- RDS:

-

Respiratory distress syndrome

- ROM:

-

Rupture of membrane

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SGA:

-

Small for gestational age

- SPE:

-

Severe preeclampsia

- SVD:

-

Spontaneous vaginal delivery

References

Roganović, J. et al. Neonatal thrombocytopenia: A common clinical problem. Paediatr. Today 11 (2), 115–125 (2015).

Ragavendran, N. et al. A Study on Risk Factors, Immediate Outcome and Short Term (3 Months) Followup of Neonate With Thrombocytopenia (Tirunelveli Medical College, Tirunelveli, 2020).

Ree, I. et al. Thrombocytopenia in neonatal sepsis: Incidence, severity and risk factors. PloS One 12 (10), e0185581 (2017).

Kumar Ray, R., Panda, S., Patnaik, R. & Sarangi, G. A study of neonatal thrombocytopenia in a tertiary care hospital: A prospective study. J. Neonatol. 32 (1), 6–11 (2018).

Bagale B. Neonatal thrombocytopenia: Its associated risk factors and outcome in NICU in a tertiary hospital in Nepal. J. Coll. Med. Sciences-Nepal. 14 (2), 65–68 (2018).

Kasap, T. et al. Neonatal thrombocytopenia and the role of the platelet mass index in platelet transfusion in the neonatal intensive care unit. Balkan Med. J. 37 (3), 150–156 (2020).

Kausar, M., Salahuddin, I. & Naveed, A. Examine the frequency of thrombocytopenia in newborns with neonatal Sepsis. Age (Days) 12, 4–8 (2020).

Ullah, S., Shah, S. H. & Khan, W. Prevalence of thrombocytopenia in neonates admitted at Rehman medical Institute Peshawar. J. Wazir Muhammad Inst. Paramedical Technol. 1 (2), 22–25 (2021).

Daşdemir, G. İ. & Çelikhisar, H. Thrombocytopenia and its effect on mortality and morbidity in the intensive care unit. (2021).

Jeremiah, Z. A., Oburu, J. E. & Ruggeri, M. Pattern and prevalence of neonatal thrombocytopenia in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Pathol. Lab. Med. Int. 2 (1), 27–31 (2010).

Onwugbolu, A. U. Prevalence of thrombocytopaenia in neonates admitted in neonatal high care unit of Pelonomi Tertiary Hospital Bloemfontein between January 2017 and June 2017 (University of the Free State, 2019).

Kebede, Z. T. et al. Hematologic profiles of Ethiopian preterm infants with clinical diagnoses of Early-Onset sepsis, perinatal asphyxia, and respiratory distress syndrome. Global Pediatr. Health 7, (2020).

Gunnink, S. et al. Neonatal thrombocytopenia: Etiology, management and outcome. Expert Rev. Hematol. 7 (3), 387–395 (2014).

Sahoo Pea. Causes, severity and outcome of neonatal thrombocytopenia in Hi-Tech medical college and hospital, Bhubaneswar 7 (Issue 7), (2022).

Sharma, A. & Thapar, K. A prospective observational study of thrombocytopenia in high risk neonates in a tertiary care teaching hospital. Sri Lanka J. Child. Health 44 (4), (2015).

Yulandari, I. R. L., Kadim, M., Amalia, P., Wulandari, H. & Handryastuti, S. The relationship between thrombocytopenia and intraventricular hemorrhage in neonates with gestational age < 35 weeks. Indonesian J. Pediatr. Perinat. Med. 56, (2016).

Yurdakök, M. et al. Immune thrombocytopenia in the newborn. J. Pediatr. Neonatal Individualized Med. (JPNIM). 6 (1), e060119–e (2017).

CSA I. Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2016: Key indicators report. Central statistics agency (CSA)[Ethiopia] and ICF Addis Ababa, and Rockville: CSA and ICF (2016).

Sahile, A., Bekele, D. & Ayele, H. Determining factors of Neonatal Mortality in Ethiopia: Investigation from the 2019 Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey (2022).

González-Luis, G. et al. Platelet counts and patent ductus arteriosus in preterm infants: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Pead. 8, 613766 (2021).

Sallmon, H. et al. Current controversy on platelets and patent ductus arteriosus closure in preterm infants. Front. Pead. 9, 612242 (2021).

Organization & (WHO). New born mortality 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/levels-and-trends-in-child-mortality-report- (2021).

Zulic, E. & Hadzic, D. Thrombocytopenia as one of the reasons of prolonged stay in the neonatal intensive care unit. Sanamed 14 (3), 241–246 (2019).

Ree, I. M. & Lopriore, E. Updates in neonatal hematology: Causes, risk factors, and management of anemia and thrombocytopenia. Hematol./Oncol. Clin. 33 (3), 521–532 (2019).

ROBERT. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 21th edition (2020).

Stanworth, S. J. Thrombocytopenia, bleeding, and use of platelet transfusions in sick neonates. Hematol. 2010 Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program Book 2012 (1), 512-6 (2012).

Carr, R. et al. Neonatal thrombocytopenia and platelet transfusion-a UK perspective. Neonatology 107 (1), 1–7 (2015).

Donato, H. Neonatal thrombocytopenia: A review. I. Definitions, differential diagnosis, causes, immune thrombocytopenia. Arch. Argentinos De Pediatria. 119 (3), e202–e14 (2021).

Mitterer, W. et al. Effects of an exclusive human-milk diet in preterm neonates on early vascular aging risk factors (NEOVASC): Study protocol for a multicentric, prospective, randomized, controlled, open, and parallel group clinical trial. Trials 22 (1), 509 (2021).

Attali, E. et al. Prolonged exposure to meconium in cases of spontaneous premature rupture of membranes at term and pregnancy outcome. J. maternal-fetal Neonatal Medicine: Official J. Eur. Association Perinat. Med. Federation Asia Ocean. Perinat. Soc. Int. Soc. Perinat. Obstet. 35 (25), 6681–6686 (2022).

Martín-Calvo, N., Goni, L., Tur, J. A. & Martínez, J. A. Low birth weight and small for gestational age are associated with complications of childhood and adolescence obesity: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev.: Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 23 (Suppl 1), e13380 (2022).

Kayton, A., Timoney, P., Vargo, L. & Perez, J. A. A review of oxygen physiology and appropriate management of oxygen levels in premature neonates. Adv. Neonatal Care 18 (2), 98–104 (2018).

Hasan, M. S., Islam, N. & Mitul, A. R. Neonatal surgical morbidity and mortality at a single tertiary center in a low-and middle-income country: A retrospective study of clinical outcomes. Front. Surg. 9, 817528 (2022).

Eslami, Z. et al. Thrombocytopenia and associated factors in neonates admitted to NICU during years 2010_2011. Iran. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 3 (1), 205 (2013).

Christensen, R. et al. Thrombocytopenia among extremely low birth weight neonates: Data from a multihospital healthcare system. J. Perinatol. 26 (6), 348–353 (2006).

Sahiledengle, B., Tekalegn, Y. & Woldeyohannes, D. The critical role of infection prevention overlooked in Ethiopia, only one-half of health-care workers had safe practice: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 16 (1), e0245469 (2021).

Houssein, N., Othman, K., Mohammed, F., Saleh, A. & Sunaallah, H. Knowledge and practices of infection prevention and control towards COVID-19 among healthcare workers in Benghazi medical centre, Libya. Khalij-Libya J. Dent. Med. Res. 5 (1), 30–42 (2021).

Tigabu Kebede, Z. et al. Hematologic profiles of Ethiopian preterm infants with clinical diagnoses of early-onset sepsis, perinatal asphyxia, and respiratory distress syndrome. Glob Pediatr. Health. 7, 2333794X20960264 (2020).

Elemam, H. H. 20 Prevalence and clinical presentation of neonatal thrombocytopenia in neonatal intensive care unit, Suez Canal university hospital. BMJ Paediatrics Open. 5 (Suppl 1), A8–A (2021).

Zaccheaus, A. & Jeremiah, J. E. O. Pattern and prevalence of neonatal thrombocytopenia in Port Harcourt (Pathology and Laboratory Medicine International, Nigeria, 2010).

Ramesh Bhat, Y. & Cherian, C. S. Neonatal thrombocytopenia associated with maternal pregnancy induced hypertension. Indian J. Pediatr. 75 (6), 571–573 (2008).

Muzammil Kausar, I. S. & Atia Naveed. Examine the frequency of thrombocytopenia in newborns with neonatal Sepsis. PJMHS 14. (2019).

Tirupathi, K., Swarnkar, K. & Vagha, J. Study of risk factors of neonatal thrombocytopenia. Int. J. Contemp. Pediatr. 4 (1), 191 (2016).

Kumar, S. & Haricharan, K. Neonatal thrombocytopenia associated with gestational hypertension, preeclampsia and eclampsia: A case-control study. Int. J. Contemp. Pediatr. 3 (1), 16–21 (2016).

Kalagiri, R. R. et al. Neonatal thrombocytopenia as a consequence of maternal preeclampsia. AJP Rep. 6 (1), e42–e47 (2016).

Eichenwald, E. C., Hansen, A. R., Stark, A. R. & Martin, C. Cloherty and Stark’s manual of neonatal care (2017).

Al-Lawama, M. et al. Prolonged rupture of membranes, neonatal outcomes and management guidelines. J. Clin. Med. Res. 11 (5), 360 (2019).

Gebreselassie, H. A. et al. Incidence and risk factors of thrombocytopenia in neonates admitted with surgical disorders to neonatal intensive care unit of Tikur Anbessa specialized hospital: A 1-year observational prospective cohort study from a low-income country. J. Blood Med. 12, 691 (2021).

Saber, A. M., Aziz, S. P., Almasry, A. Z. E. & Mahmoud, R. A. Risk factors for severity of thrombocytopenia in full term infants: A single center study. Ital. J. Pediatr. 47 (1), 7 (2021).

Ayadi, I. D., Hamida, E. B., Youssef, A., Sdiri, Y. & Marrakchi, Z. Prevalence and outcomes of thrombocytopenia in a neonatal intensive care unit prévalence et pronostic de La thrombopénie Dans Une unité de réanimation néonatale. Tunis. Med. 94(4). (2016).

Bhat, R., Kousika, P., Lewis, L. & Purkayastha, J. Prevalence and severity of thrombocytopenia in blood culture proven neonatal sepsis: a prospective study. Arch. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. 6(2). (2018).

Al Saleh, K. & AlQahtani, R. M. Platelet count patterns and patient outcomes in sepsis at a tertiary care center: Beyond the APACHE score. Medicine 100 (18), e25013 (2021).

Christensen, R. D. et al. Thrombocytopenia in small-for-gestational-age infants. Pediatrics 136 (2), e361–e370 (2015).

Roberts, I. A. G. & Chakravorty, S. 44: Thrombocytopenia in the newborn. in (ed Michelson, A. D.) Platelets (Fourth Edition) 813–831 (Academic, 2019).

Bonifacio, L., Petrova, A., Nanjundaswamy, S. & Mehta, R. Thrombocytopenia related neonatal outcome in preterms. Indian J. Pediatr. 74 (3), 269–274 (2007).

Maheshwari, A. Role of platelets in neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Pediatr. Res. 89 (5), 1087–1093 (2021).

Song, R., Subbarao, G. C. & Maheshwari, A. Haematological abnormalities in neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. J. Maternal-Fetal Neonatal Med. 25 (sup4), 14–17 (2012).

Brown, R. E. et al. Effects of sepsis on neonatal thrombopoiesis. Pediatr. Res. 64 (4), 399–404 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express deeper gratitude and special thanks to our language expert and research expert, Dr. Tadesse Weldegebreal Baymot (MSc, PhD, Department of English language and literature, College of Social Sciences and Humanities, University of Gondar) and Mr. Ayenew Molla Lakew (Assistant Professor, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Institute of Public Health, University of Gondar) for timely language translation and evaluation of the data collection tool, respectively.

Funding

The University of Gondar has funded to conduct this work, but there is no fund for publication process.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ATA: conceptualized the study and was involved in design, analysis, interpretation, report and manuscript writing. GDG: involved in analysis, interpretation, report, and manuscript writing. CWK: involved in analysis, interpretation, report, and manuscript writing. MMK: involved in analysis, interpretation, report, and manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abate, A.T., Gedefaw, G.D., Kassahun, C.W. et al. Prevalence and associated factors of thrombocytopenia among neonates in Northwest Amhara region comprehensive specialized hospitals, Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Sci Rep 15, 12610 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93042-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93042-0