Abstract

A coherence algorithm is used to detect and classify electrical faults in the stator windings of the induction machine in this paper. The approach can definitely define turn-to-turn and internal shunt faults that occur on the three-phase machine windings. It can also distinguish between the diverse types of the internal shunt faults. The approach requires the acquisition of three-phase voltage measurements at the midpoints and complete terminals of the stator windings of the induction machine. The function of the numerical differential voltage relay can be performed using cross-coherence and auto-coherence coefficients quantified for the voltage measurements to determine and categorize the various faults. A modified configuration for the three-phase stator windings of an induction motor is used to test the technique; in which, each stator winding of the equipment is re-wounded to obtain 20 taps per phase. This configuration aims to construct voltage transformers at the midpoints and complete terminals for the machine stator windings, and to facilitate making comprehensive tests to ensure the effectiveness of the coherence technique. The testing results demonstrate the effectiveness and efficiency of the advanced protection. The experimental findings indicate that the protection’s dependability and security percentages are greater than 98.0%, and the protection’s reliability and accuracy rates are nearly 97.0%. The coherence measure has the ability to discover winding faults, particularly those occurring from turn to turn, differentiate between fault locations, and categorize shunt faults located within the machine protection zone. Additionally, the proposed approach has a high-speed response that is adjustable, and new tripping curves are created.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electrical machines remain an integral part of power grids. Because of their multiple applications, the machines may be susceptible to a variety of faults that need to be diagnosed and repaired1. It is imperative to create and develop protection and measurement techniques that facilitate the fast identification and precise evaluation of diverse machine problems within the industry. The establishment of practical and microprocessor-driven systems/processes for fault evaluation and the development of extensive methods permit users to adopt the most appropriate approach for fault diagnosis and analysis2. Most faults are dedicated to the stator windings of the AC machines. Winding faults are common due to high temperatures, short-circuit currents, mechanical stresses, magnetic forces and insulation breakdown3,4. In general, fault diagnosis methods for the machine stator windings use magnetic flux, voltage, current, reactive power, or a combination of them. Despite being more serious than the turn-to‐turn winding faults, the line‐to‐line and line‐to‐ground faults can be identified easier by protective relays within a fraction of a second5. It is difficult to detect the turn-to‐turn fault at the initial stage because it does not remarkably affect the two terminal winding currents. Thus, it is imperative to monitor inter-turn faults in order to diagnose their onset and avert any machine failure. The insulation breakdown is not serious at the first stage, however, if it is not identified early, it may result in a dangerous fault6. Actually, a high‐induced current, which originates due to the inter-turn fault in the winding, circulates in the shorted turns and may lead to winding deterioration and machine malfunction7. Early fault detection can reduce a machine’s degradation, which can be maintained by rewinding its defective winding and putting it back into service8. Numerous researches were presented to diagnose the faults in AC machine stator windings.

In9, a slope of a Lissajous curve was measured to ascertain the inter-turn faults in turbo‐generators. In10,11, the magnetic flux sensors were used to figure out Turn-to-Turn Fault (TTF) in induction machine stator windings. These sensors possess the capability to measure the air-gap and stray magnetic fields with significant sensitivity. In12, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and current signature analysis were used to diagnose machine faults. The CNNs algorithm was used to find different faults in machine windings, which automatically removed relevant features from the current measurements. In13, a combination of machine learning and wavelet transform was used to figure out and diagnose faults. The technique of wavelet transform was harnessed for features extraction from machine output, while the technique of machine learning was exploited for faults classification, which increased the accuracy of the protection. In14, a fault diagnosis was accomplished using a combination of transfer learning and few-shot learning to protect asynchronous machines. In15, the effectiveness and robustness of the approach were increased by integrating the outputs of multiple deep learning (DL) models for machine faults diagnosis. In16, the precision of faults detection and classification was enhanced by the integration of machine learning with wavelet packet decomposition by extracting detailed frequency information. In17, edge computing was applied to identify faults online for induction machines. Low-latency fault detection was achieved by applying machine learning models to edge devices. In18, a Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)-based algorithm was integrated with Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs)-based algorithm to diagnose machine faults. The integrated model effectively captured both spatial and temporal features from machine measurements.

Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors (PMSMs) are extremely popular in industrial applications because of their high-efficiency and large power rating19. The machine windings may be damaged if turn-to-turn faults are not promptly detected and segregated19. As a consequence, it is indispensable to detect online turn-to-turn faults in order to protect the machine windings. Numerous researches were published to diagnose and analyze the turn-to-turn faults situated on the windings of the electrical AC machine. In20, current waves were analyzed using a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to figure out the turn-to-turn faults. The number of short-turns and the fault location could be determined by using a low-voltage supply of PMSM excitation at the motor standstill state, along with the resistance and inductance obtained from the current data21. In22, online fault detectors used the square of the negative-sequence components of the machine measurements. With regard to great security requirements, a Dual-Redundancy Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor (DRPMSM) can continue to function when a fault takes place on one of the dual windings per phase. Turn-to-turn faults within the DRPMSM were detected using the direct axis voltage measurements and imaginary power23,24. However, the method of assessment is complicated under diverse operating loads, and discrete values with a fixed sampling rate lacked the capability of fault diagnosis as the fault indicator oscillates uncommonly at a low machine rotation. In25, only inter-turn faults situated within the machine windings were detected by the auto-correlation technique. In25, the method was unable to distinguish between the faults inside and outside the machine protection zone and could not classify the different faults. Recently, numerous advanced techniques were employed for diagnosis and analysis of turn-to-turn faults, including but not limited to Improved Vague Support Vector Machine (IVSVM)26, Bayesian networks27, Support Vector Machines (SVM)28, and Parzen window29. In30, a hybrid CNN-LSTM model was applied to detect machines faults. The fault detection performance was enhanced by using the CNN-based algorithm that used to extract features from the analog measurements and the LSTM-based algorithm that used to capture temporal dependencies. In31, an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) was successfully applied to diagnose winding faults. In32, an infrared thermography device was used to identify temperatures and hotspots in diverse locations of the windings. Thermography was used in induction motors for monitoring fault condition. The high cost of the infrared apparatus is the primary demerits of the thermal monitoring method.

Stator winding voltages or currents are the most common measurement for machine fault diagnosis, since they are acquired using instrument transformers or probes33. The current/voltage-based methods do not require extra sensors, and they are more reliable than the magnetic flux‐based methods33. For an AC machine winding with multiple branches, comparing the different branch currents serves as a differential TTF protection33. In this approach, the currents in various branches of a stator winding are compared. In a healthy situation, the differential current is nearly zero, while, it increases and circulates between the shorted turns when a winding TTF occurs33.

Traditional differential voltage/current protections were based on voltage/current phasors34. A critical problem with differential current relays of the longitudinal type arises when turn-to-turn faults happen in the same winding, which leads to a reduced turns due to the short-circuit event35. The reduced number of turns involved in the fault decreases the circulating short-circuit currents, which can blind the conventional differential protection. The machine windings protection against earth leakage faults is performed with the restricted earth fault protection, which has a greater sensitiveness than the differential current protection36,37. However, the restricted earth fault relay can be used to protect the machine against only grounding and asymmetric faults, which resembles a backup protection for the primary differential protection, and more specified specifications for instrument transformers should be taken into account36,37. Another method that is applicable to identify the TTF in machine windings is based on the residual voltage38. In order to measure the neutral voltage, an extra open delta voltage transformer is created. In the healthy machine, the sum of the three phase voltages of the open delta voltage transformer is about zero. Whereas, the residual voltage is no longer zero in the case of TTF. In this approach, the sum of the third harmonics is non‐zero, which must be eliminated to avoid undesirable machine tripping38. The additional VT is not financially feasible and may cause some installation problems in some cases. To obviate the utilization of additional VT, a zero‐sequence voltage (ZSV) can be calculated in lieu of measuring it38. In38, a protection scheme was used to compute the zero‐sequence voltage (ZSV) instead of measuring it. Because of the inherent asymmetry of the AC machine, the ZSV is not always zero even in the healthy setting. Thus, a threshold should be taken into account. When the ZSV is greater than the threshold value, a turn-to-turn fault was observed on the winding.

In39,40, the two methods aim to detect the faults and measure the asymmetry of the electrical signals taken at the machine load terminals. In39, the method was dependent on the alienation estimator for voltage and current waves. In40, the coherence coefficients were calculated for the machine waveforms. Therefore, the alienation-based algorithm39 takes longer to detect faults than the coherence-based algorithm40. In39,40, the approaches failed to (1) detect inter-turn faults, (2) distinguish between faults inside and outside the machine protection area, (3) classify the ten shunt faults that are located within the machine protection region, and (4) select the faulty phase(s) of the three-phase machine windings. To address these issues, a smart differential voltage protection based on the coherence coefficients estimated for only voltage signals is proposed. Recently, the coherence algorithm was previously used to establish an automatic power factor corrector (APFC)41, a synchronization system42, a busbar protection scheme43, and a detection and measurement tool for imbalance and disturbance of three-phase generator voltages and currents44. Hence, cross-coherence and auto-coherence coefficients for the voltage waves can be used to diagnose faults on the stator windings of the three-phase machines. The proposal requires the three-phase voltage measurements at the midpoint and full terminal of each phase stator winding of the machine. The methodology is empirically validated on a three-phase AC machine. To accomplish extensive experimental tests on various turns and windings of the AC machine, the windings have been re-winded to get 20 taps for each phase. Furthermore, this configuration allows for different turn-to-turn, external, and internal faults with respect to the machine protection zone to be implemented.

The present manuscript mainly consists of the following: the fundamentals of the differential voltage protection based on the coherence technique are amply illustrated in Section “Coherence-based differential voltage protection”. A practical system for examining the protection algorithm is described in Section “Experimental system”. The practical results will be documented and analyzed in Section “Testing results analysis”. In Section “Protection characteristics”, the algorithm’s characteristics are assessed, its merits are discussed, and it is compared to other recent methods. The algorithm’s assumptions are introduced in Section “Algorithm assumptions”, and the main contributions are listed in Section “Contributions”. Finally, the main conclusions are drawn in Section “Conclusions”.

Proposal characteristics

The test results affirm that a coherence-based differential voltage protection has the following merits:

-

(1)

A novel coherence-based technique of differential voltage relay for AC machine windings is presented,

-

(2)

The windings of a variety of equipment, such as power transformers and AC machines, can be protected by a modified wiring circuit for the differential voltage protection,

-

(3)

The coherence indicators can be used to pinpoint the moment of fault presence,

-

(4)

Continuous monitoring of coherence trajectories can be accomplished,

-

(5)

The methodology can find turn-to-turn and shunt faults,

-

(6)

The algorithm can be integrated with other digital systems to enhance protection redundancy and reliability for protecting the windings of large-scale equipment,

-

(7)

A new configuration for tripping curves dependent on both cross-coherence and auto-coherence indicators is developed for the protection method to distinguish between turn-to-turn, external, and internal faults,

-

(8)

The technique can be used to classify shunt faults inside the protection zone of the machine using cross-coherence indicators,

-

(9)

The algorithm can quantify the tripping time in the incidence of turn-to-turn faults,

-

(10)

The ratios of asymmetry and disturbance for the three-phase voltages can be evaluated by utilizing the cross-coherence and auto-coherence indicators, respectively,

-

(11)

The advanced approach achieves high rates of speed, security, dependability, reliability, and accuracy,

-

(12)

It is possible to protect single-phase or three-phase machine windings with the coherence algorithm,

-

(13)

The algorithm sends a tripping permission when turn-to-turn or internal shunt faults occur, while it is restricted in the cases of external faults or normal operations,

-

(14)

The protection requirements rely on numerical values of coherence settings and the size of the data window. The coherence settings can be used to set tripping and blocking zones within the proposed characteristic curves of the relay, and the data window is useful for controlling the computation time of the coherence algorithm. Consequently, the approach can modify protection attributes,

-

(15)

Arithmetic calculations are not used to determine coherence settings, and.

-

(16)

The parameters of electrical machines and power system components are not required for the algorithm to work.

Generalized comparison

Table 1 compares the developed method with some existing methods used to diagnose different faults situated on the stator windings of the AC machines.

Coherence-based differential voltage protection

The main parameters of a power quality are the frequency, RMS value, phase difference, symmetry, and wave appearance. A fault in the electrical machine windings can cause a change in at least one of these parameters. The coherence technique is an appropriate tool to define a fault emergence and measure the correlation between any two data sets of one or two variable(s)39,40. The coherence algorithm can perform the roles of fault detection and unbalance assessment between two data sets using the same arithmetic operation at the same time. In consequence, it can be harnessed to create an effective and reliable scheme for windings protection for multiple electrical machines, such as synchronous generators and motors, induction generators and motors, and power transformers40,41. The auto-coherence indicator and cross-coherence indicator are two distinct types of coherence indicators that can be used in this work42,43,44. The proposed method aims to obtain three-phase voltages, which are measured at the midpoints and full ends for the windings of the AC machine. For each phase winding, the VTR1 of the voltage transformer (VTX1) at the full end is double the VTR2 of the voltage transformer (VTX2) at the midpoint. The auto-coherence and cross-coherence indicators computed for the voltages can be used to detect and discriminate faults in the proposal of differential voltage protection. The cross-coherence indicator represents the main protection algorithm, while the auto-coherence indicator is considered the backup protection algorithm. The cross-coherence indicator, which is estimated between each two voltage signals of the same phase winding of the machine, can be used to identify and classify internal shunt faults in the differential voltage protection. Hence, the cross-coherence indicator resembles a conventional differential voltage relay, where it can compare the similarity between the two voltages, and it can function for every distinct phase. Whereas, the auto-coherence indicator can be used to determine faults in general, including winding-to-winding, winding-to-neutral, and turn-to-turn faults. The subsequent section will delineate the mathematical equations applicable to both types of coherence.

Coherence indicators

Cross-coherence indicator

The cross-coherence indicator can be exploited to quantify the correlation, as a function of frequency, between two different variables. Its amount extends from 0.0 to + 1.0, which is similar to the value per unit41,42. The cross-coherence indicator is computed (between each two conforming data sets) for the two voltages (v1x(n) and v2x(n)) measured for the ‘X’ phase of the induction machine stator windings41,42. The arithmetic operation is done continuously. The quantity of measurements per the data set corresponds to the quantity of measurements per a single cycle (Ns = Nc) of the fundamental power frequency for the machine voltage signals. For the three-phase induction motor stator windings, three cross-coherence indicators, namely Cv12a, Cv12b, and Cv12c, can be obtained43,44. The mathematical formula for the cross-coherence indicator (Cv12x(k)) computed between the two voltages (v1x(n) and v2x(n)) taken at the midpoint and complete terminal of the phase stator winding ‘X’ can be expressed as follows40:

where \(V_{1x1} (k) = \sum\limits_{n = 0}^{N - 1} {\left[ {v_{1x} (n) \cdot \cos \left( {\frac{2\pi kn}{N}} \right)} \right]}\), \(V_{1x2} (k) = \sum\limits_{n = 0}^{N - 1} {\left[ {v_{1x} (n) \cdot \sin \left( {\frac{2\pi kn}{N}} \right)} \right]}\), \(V_{2x1} (k) = \sum\limits_{n = 0}^{N - 1} {\left[ {v_{2x} (n) \cdot \cos \left( {\frac{2\pi kn}{N}} \right)} \right]}\), \(V_{2x2} (k) = \sum\limits_{n = 0}^{N - 1} {v_{2x} (n) \cdot \sin \left( {\frac{2\pi kn}{N}} \right)}\)where V1x1(k): The cosine term of the DFT for the voltage signal v1x(n), V1x2(k): The sine term of the DFT for the voltage signal v1x(n), V2x1(k): The cosine term of the DFT for the voltage signal v2x(n),and V2x2(k): The sine term of the DFT for the voltage signal v2x(n),

Auto-coherence indicator

The auto-coherence indicator can be used to figure out the interrelationship, as a function of frequency, between each couple of successive data groups of the same variable. The two data sets are separated by one cycle. Its value can be between 0.0 and + 1.039,40. The auto-coherence indicator can be computed for each voltage wave measured at the midpoint and complete terminal of each stator winding. This estimation process is performed between each two successive data groups that differ in time by a cycle of the nominal power frequency42,43. In this study, the presetting data window can be set to a sub-cycle, but it will be taken as a single cycle. This is related to the protection requirements and the prevailing conditions in a power grid. Six voltage signals are acquired from the three-phase windings of the induction machine, leading to six auto-coherence indicators (Cv1a, Cv1b, Cv1c, Cv2a, Cv2b, and Cv2c) can be estimated39,40. The mathematical equation for the auto-coherence indicator (Cv1x(k)) can be formulated for the full voltage (v1x(n)) of the phase ‘X’ stator winding of the induction motor as follows40:

where V3x1(k): The cosine term of the DFT for the voltage wave v1x(n-Nc), and V3x2(k): The sine term of the DFT for the voltage wave v1x(n-Nc).

Moreover, the mathematical equation for the auto-coherence (Cv2x(k)) can be computed for the midpoint voltage (v2x(n)) of the phase ‘X’ stator winding of the induction motor, as given below40.

where V4x1(k): The cosine term of the DFT for the voltage wave v2x(n-Nc), and V4x2(k): The sine term of the DFT for the voltage wave v2x(n-Nc).

The subscript X is the designated phase A, B, or C.

Faults detection and localization

Table 2 includes the operation conditions of the coherence technique and its behavior. The machine condition is what determines the protection action.

Tripping curve based on coherence

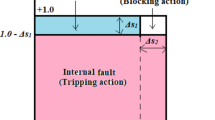

The computational technique works separately for each phase of the IM stator winding. The tripping curve, which is derived from the single-phase coherence factors (Cv12x, Cv1x, and Cv2x), is depicted in Fig. 1. It has a square form, and it can be partitioned into three areas that are defined below:

-

(1)

The normal operation/external fault area: The blocking order is issued to prevent isolating the induction machine circuit breakers,

-

(2)

The turn-to-turn fault/external fault area: The tripping permission is sent to separate the induction machine circuit breakers when the turn-to-turn faults occur; whereas, the blocking order is issued in the state of external faults, and

-

(3)

The internal shunt fault area: The tripping permission is sent to disconnect the induction machine circuit breakers to protect it from the internal faults.

Table 3 includes the operating time of the algorithm for different machine conditions. The table demonstrates that the operating time is infinite in normal operating conditions and instantaneous when internal faults occur. To ensure the turn-to-turn fault occurrence, the actual tripping time of the protection algorithm should initiate after the starting time of the motor.

To estimate the tripping time (Tvop) in the incidence of turn-to-turn fault, the following expression can be applied. The formula requires the coefficient (Kvx) computed using the peaks’ ratio of the two voltage signals (v1x and v2x) for phase X, the pickup ratio (Kvpu), and the time multiplier (Ks).

where Tvop: The quantified tripping time of the algorithm (s), Ks: The time multiplier (in this algorithm, Ks is selected 0.1), Kvpu: The predetermined pickup ratio of the relay (in this algorithm, Kvpu is selected 0.95), Kvx: The coefficient computed using the peaks’ ratio of the two voltage signals (v1x and v2x) for phase X, v1xpeak: The measured peak value of the voltage signal v1x (n), and v2xpeak: The measured peak value of the voltage signal v2x (n).

Protection strategy

The method mechanism for identifying and distinguishing turn-to-turn, external and internal faults is illustrated in Fig. 2. The protection procedure can be executed for each phase as given below.

-

(1)

Take the voltage measurements (v1x and v2x) at the midpoints and supply terminals for the stator windings of the induction machine,

-

(2)

Convert the voltage waves into discrete values using a Data Acquisition Card (DAC),

-

(3)

Select the sampling size for a single cycle (Nc), and the sampling size for the data set (Ns),

-

(4)

Specify the coherence presetting divergences (Δx1, and Δx2). Where,

-

Δx1 is the presetting divergence of the cross-coherence indicator (Cv12x), and.

-

Δx2 is the presetting divergence of the auto-coherence indicators (Cv1x and Cv2x),

-

-

(5)

Quantify the phase coherence indicators (Cv12x, Cv1x, and Cv2x) for the voltage signals, and the coefficient (Kvx),

-

(6)

Execute the operation conditions of the coherence methodology for each phase (as presented in Table 2 and the flow chart in Fig. 2),

-

(7)

Compute the tripping time (Tvop) in the incidence of turn-to-turn fault,

-

(8)

Classify the shunt faults existing within the machine protection zone (as shown in Fig. 3a,b),

-

(9)

Carry out the following protection actions:

-

(a)

Inactive action Block the machine breakers in the state of healthy phase X,

-

(b)

Inactive action Block the machine breakers in the state of external faults for the phase X,

-

(c)

Active action Trip the machine breakers in the state of internal shunt faults for the phase X, and.

-

(d)

Active action Trip the machine breakers in the state of turn-to-turn faults for the phase X.

-

(a)

-

(10)

Originate a tripping permission for the AC machine breakers when the machine is prone to internal shunt faults or turn-to-turn faults, and

-

(11)

To differentiate between ground and non-ground faults, calculate the neutral voltage (v1n and v2n) and apply the following condition: If v1n = v1a + v1b + v1c = 0.0, or v2n = v2a + v2b + v2c = 0.0, the fault is then free from the ground. Otherwise, the fault is through the ground.

Algorithm speed

The computation time and fault detection speed depend on the size of the selected data set applied to estimate the coherence coefficients. The computation time can be modified depending on the data set. It can be equal to or less than one cycle of the nominal power frequency. Its quantity is affected by the protection requirements and the operating conditions of the machine. Furthermore, the response speed of the digital protection has an immediately interrelated and interdependent relationship with the following items:

-

(1)

Its microprocessor speed,

-

(2)

The load of computer programming, and

-

(3)

The sophistication level of the computer programming.

Coherence settings criteria

In this work, the coherence presetting values have been investigated on a new setup for an induction motor with tapping three-phase windings. Practically, the coherence threshold values have been modified and verified by seeing the relay response signal and annunciator flag, which provides information on the state of the electrical model to indicate that the protection system is active or non-active. LABVIEW program has been used to adjust the numerical values of the coherence settings, and bypass acceptable imbalances and normal operations. The settings can be easily modified with other experimental models, depending on how much unbalance of the three-phase voltages is acceptable. This is a considerable benefit that can boost the reliability of the suggested technique.

Moreover, the coherence settings possess the capability to regulate the requirements of the protection properties, comprising sensitivity, security, dependability, and speed. Using a feasible data sets and coherence presetting values can actually mitigate the impacts of instrumentation errors, transient faults, and light harmonics. Consequently, the protection response is conditioned on the actual values of the coherence indicators and the coherence pickup values of the protection system.

Protection algorithm sensitivity

The sensitivity of the coherence algorithm is closely associated with the actual coherence indicators (Cv12x, Cv1x and Cv2x) and the coherence threshold value (Cvpu), as shown in Eqs. (6–8).

Additionally, the sensitivity of the second algorithm depends on the pickup ratio (Kvpu), and the coefficient (Kvx) by comparing the peaks’ ratio of the two voltage signals (v1x and v2x) for phase X, as illustrated in Eq. (9).

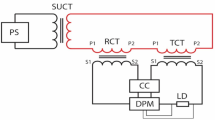

Experimental system

The experimental system includes a three-phase power supply with a line voltage rating of 380.0 V, a three-phase supply miniature circuit breaker (CB) with a current rating of 63.0 A, and an induction motor (IM) with a power rating of 2.90 kW. For each stator winding of the AC machine, a voltage transformer (VTX2) with a turns’ ratio of 220/6 is installed at the midpoint of the winding, and a second voltage transformer (VTX1) with a turns’ ratio of 220/3 is built at the complete terminal of the winding. The three-phase stator windings of the machine have been re-wounded, where 20 taps per each phase winding have been created. This taps configuration aims to construct voltage transformers at the midpoints and complete terminals of the machine stator windings, and to facilitate testing comprehensive experiments to verify the effectiveness of the coherence technique. Diverse scenarios of shunt and series faults on the motor windings will be examined and analyzed, including winding-to-winding, winding-to-neutral, and turn-to-turn faults. A plot of the three-phase induction machine with 20 taps per phase winding is depicted in Fig. 4a. The wiring connection diagram of the induction motor, comprising of 20 taps per phase stator winding, two voltage transducers per each phase, a conversion tool for analog-to-digital signals, and a LABVIEW program accessible on a personal laptop, is shown in Fig. 4b. The parameters’ specifications for the experimental system elements are enumerated in Appendix 1. This project has been undertaken in the electrical power laboratory at Misr University for Science and Technology (MUST) in Egypt.

Testing results analysis

In this article, the analog-to-digital converter and the LABVIEW package are utilized to test the differential voltage protection under numerous kinds of external, internal and turn-to-turn faults. The USB-6009 analog-to-digital converter, manufactured by National Instruments, is used to convert AC voltage signals into discrete values. The converter will be set to run in differential mode with a sampling frequency of 2.5 kHz. Two voltage transducers are used for each phase to measure the voltage waveforms, which resemble the analog input to the converter, and the LABVIEW platform is used as a monitor screen for the machine status. This implies that six voltage transducers are set up for the three-phase machine stator windings. The voltage waveforms taken from the two voltage transducers are used to obtain the three coherence indicators (Cv12x, Cv1x, and Cv2x) for each phase winding ‘X’. Appendix 2 contains input data for the developed technique. In this section, the results for phase winding ‘A’ of the motor will be presented. Table 4 contains the output findings for different scenarios of faults. The table also displays the types of protection response.

Case 1: normal operation (phase A)

Figure 5a–d illustrate the experimental results for case 1. This instance is healthy phase A. The two voltages (v1a and v2a) of the phase A stator winding are presented in Fig. 5a. The cross-coherence indicator (Cv12a) calculated between the two phase A voltages is depicted in Fig. 5b. Figure 5c shows the blocking signal, which signifies a zero value during the full display time. Figure 5d describes the auto-coherence indicators (Cv1a and Cv2a) quantified for the two voltages of the phase A. As depicted in Fig. 5, the obtained findings indicate that the equipment state is normal. It is observed that the two voltage waves (v1a and v2a) are identical, and there is no voltage difference between them. The values of the coherence indicators (Cv12a, Cv1a and Cv2a) are roughly unity. This results in the differential voltage protection based on the coherence indicators being constrained in this test. Consequently, the tripping time of the protection algorithm is infinite.

The experiments on internal shunt faults, spanning from case number 2 to case number 9), will be discussed below.

Case 2: internal shunt fault (A11–B11)

Figure 6a–d manifest the experimental results for case 2. Case 2 involves an internal shunt fault (A11–B11). Figure 6a exhibits the two voltages (v1a and v2a) of the phase A stator winding for the machine. Figure 6b exhibits the cross-coherence indicator (Cv12a) quantified between the two voltages of phase A. Figure 6c depicts the protection tripping signal, and Fig. 6d displays the auto-coherence indicators (Cv1a and Cv2a) computed for the two voltages of phase A. The results of the shunt internal fault (A11–B11) for the machine windings are illustrated in Fig. 6. The two voltages (v1a and v2a) are dissimilar in the presence of the internal shunt fault, where there is a difference between the voltages. In this test, the quantities of the coherence indicators (Cv12a, Cv1a and Cv2a) are nearly + 0.30, + 0.95 and + 0.95, respectively, during the internal fault occurrence. As a result, the developed approach based on the coherence statistic is active because of the presence of internal fault (which happens between the two phases A and B windings at tap 11). It is clear that the cross-coherence amplitude (Cv12a) is close to + 0.30, which assures the internal fault event. In experiment 2, the protection tripping time is instantaneous.

Case 3: internal shunt fault (A11–C11)

Figure 7a–d show the experimental results for case 3. Case 3 is an internal shunt fault (A11–C11). Figure 7a exhibits the two voltages (v1a and v2a) of the phase A for the machine, Fig. 7b presents the cross-coherence indicator (Cv12a). Figure 7c depicts the protection tripping signal, and Fig. 7d introduces the auto-coherence indicators (Cv1a and Cv2a) estimated for the two voltages of phase A. The results of the machine stator windings during the internal fault (A11–C11) are shown in Fig. 7. The two voltages (v1a and v2a) differ in the presence of the internal fault, resulting in a differential voltage in the relay. In this case, the amounts of the coherence indicators (Cv12a, Cv1a and Cv2a) are roughly + 0.30, + 0.95 and + 0.95, respectively, during the fault time. Thus, the present approach is active due to the occurrence of internal fault (which occurs between the two phases A and C windings at tap 11). It is evident that the cross-coherence amplitude (Cv12a) is close to + 0.30, indicating the internal fault situation. In test 3, the protection tripping time is instantaneous.

Case 4: internal shunt fault (A12–B12)

Figure 8a–d demonstrate the experimental results for case 4. Case 4 is an internal shunt fault (A12–B12). Figure 8a exhibits the two voltages (v1a and v2a) for the equipment. The cross-coherence indicator (Cv12a) is presented in Fig. 8b. The relay tripping signal is depicted in Fig. 8c, and the auto-coherence indicators (Cv1a and Cv2a) are introduced in Fig. 8d. The results of the machine stator windings during the internal fault (A12–B12) are shown in Fig. 8. The two voltages (v1a and v2a) are different during the period of internal fault, creating a differential voltage in the protective relay. In this case, the values of the coherence indicators (Cv12a, Cv1a and Cv2a) are approximately + 0.25, + 0.97 and + 0.30, respectively, during the fault span. This causes the present approach to be active during the extent of internal fault. It is obvious that the cross-coherence amplitude (Cv12a) is close to + 0.25, which confirms the internal fault incidence. Consequently, the protection sends a tripping permission, and its operating time is instantaneous.

Case 5: internal shunt fault (A12–C12)

Figure 9a–d show the experimental results for case 5. Case 5 is an internal shunt fault (A12–C12). Figure 9a exhibits the two voltages (v1a and v2a) for the phase A stator winding of the machine. Figure 9b presents the cross-coherence indicator (Cv12a). Figure 9c depicts the protection tripping signal, and Fig. 9d introduces the auto-coherence indicators (Cv1a and Cv2a). The results of the phase A stator winding during the internal fault (A12–C12) are shown in Fig. 9. The two voltages (v1a and v2a) originate a differential voltage during the internal fault period. In this experiment, the values of the coherence indicators (Cv12a, Cv1a and Cv2a) are about + 0.22, + 0.97 and + 0.97, respectively, when the internal fault occur. Thus, the present technique is active because of the occurrence of internal fault. It is apparent that the cross-coherence quantity (Cv12a) is close to + 0.22, which affirms the internal fault condition. Therefore, the relay operating time is instantaneous in case 5.

Case 6: internal shunt fault (A13–B13)

Figure 10a–d illustrate the practical results for case 6. Case 6 is an internal shunt fault (A13–B13). Figure 10a demonstrates the two voltages (v1a and v2a). Figure 10b displays the cross-coherence indicator (Cv12a). Figure 10c offers the protection tripping signal, and Fig. 10d presents the auto-coherence indicators (Cv1a and Cv2a). The results of the phase A stator winding of the machine during the internal fault (A13–B13) are introduced in Fig. 10. The two voltages (v1a and v2a) create a differential voltage in the relay due to the internal fault existence. In this incidence, the values of the coherence indicators (Cv12a, Cv1a and Cv2a) are approximately + 0.20, + 0.97 and + 0.30, respectively, during the internal fault time. Thereby, the occurrence of the internal fault causes the algorithm to become active. It is seen that the value of cross-coherence (Cv12a) is nearly + 0.20, which signifies the internal fault situation. As a result, the protection algorithm issues a tripping action to the machine, and its operating time is instantaneous in test 6.

Case 7: internal shunt fault (A13–C13)

Figure 11a–d illustrate the practical results for case 7. Case 7 is an internal shunt fault (A13–C13). Figure 11a presents the two voltages (v1a and v2a) of the phase A stator winding for the machine. Figure 11b depicts the cross-coherence indicator (Cv12a). Figure 11c exhibits the relay tripping signal, and Fig. 11d shows the auto-coherence indicators (Cv1a and Cv2a). The results of the phase A stator winding for the machine during the shunt internal fault (A13–C13) are illustrated in Fig. 11. The dissimilarity of the two voltages (v1a and v2a) causes a differential voltage during the extent of internal fault. In this experiment, the quantities of the coherence indicators (Cv12a, Cv1a and Cv2a) are roughly + 0.20, + 0.97 and + 0.97, respectively, during the fault span. Therefore, the presence of internal fault activates the algorithm. It is observed that the cross-coherence quantity (Cv12a) is nearly + 0.20, which confirms the internal fault incidence. In consequence, the relay operating time is instantaneous in test 7.

Case 8: internal shunt fault (A14–B14)

Figures 12a–d present the practical results for case 8. Case 8 is an internal shunt fault (A14–B14). Figure 12a manifests the two voltages (v1a and v2a) of the phase A stator winding for the machine. Figure 12b shows the cross-coherence indicator (Cv12a). Figure 12c introduces the protection tripping signal, and Fig. 12d depicts the auto-coherence indicators (Cv1a and Cv2a). The results of the phase A stator winding for the machine during the internal fault (A14–B14) are presented in Fig. 12. During the period of internal fault, the difference between the two voltages (v1a and v2a) originates a differential voltage in the relay. In this case, the values of the coherence indicators (Cv12a, Cv1a and Cv2a) are approximately + 0.18, + 0.97 and + 0.23, respectively, during the fault time. Therefore, the event of internal fault activates the proposed algorithm based on the coherence statistic. It is obvious that the cross-coherence coefficient (Cv12a) is nearly + 0.18, which assures the existence of the internal fault. Consequently, the protection tripping time is instantaneous in test 8.

Case 9: internal shunt fault (A15–C15)

Figure 13a–d introduce the obtained results for case 9. Case 9 is an internal shunt fault (A15–C15). Figure 13a illustrates the two voltages (v1a and v2a) of the phase A stator winding for the machine. Figure 13b depicts the cross-coherence estimator (Cv12a). Figure 13c illustrates the protection operating announcement, and Fig. 13d presents the auto-coherence estimators (Cv1a and Cv2a). The outcomes of the phase A stator winding for the machine during the internal fault time (A15–C15) are shown in Fig. 13. During the time of fault, the difference between the two voltages (v1a and v2a) causes a differential voltage in the protective relay. In this experiment, the quantities of the coherence estimators (Cv12a, Cv1a and Cv2a) are roughly + 0.10, + 0.98 and + 0.15, respectively, during the fault time. Thus, the incidence of internal fault activates the developed approach based on the coherence technique. It is evident that the cross-coherence estimator (Cv12a) is about + 0.10, which confirms the presence of the internal fault. In consequence, the protection tripping time is instantaneous in test 9.

The experiments on turn-to-turn faults (spanning from case number 10 to case number 13) will be presented below. Quantitative findings for the incidences of turn-to-turn fault are contained in Table 5.

Case 10: turn-to-turn fault (A1–A3)

Figure 14a–d illustrate the experimental results for case 10. Case 10 is a turn-to-turn fault (A1–A3). Figure 14a displays the two voltages (v1a and v2a) of the phase A stator winding for the machine. Figure 14b depicts the cross-coherence estimator (Cv12a). Figure 14c illustrates the protection tripping signal, and Fig. 14d presents the auto-coherence estimators (Cv1a and Cv2a). The results of the phase A stator winding for the machine during the fault period of the turn-to-turn (A1–A3) are depicted in Fig. 14. During the fault period, there is a small difference between the two voltages (v1a and v2a), which causes a differential voltage in the protection. In this experiment, the values of the coherence estimators (Cv12a, Cv1a and Cv2a) are approximately unity, and the factor Kva≈ 0.906 that is less than Kvpu = 0.95 during the fault span. These findings affirm the incidence of turn-to-turn fault. Therefore, the fault activates the proposed technique. As a result, the protection tripping time is Tvop≈ 2.060 s, as given in Table 5.

Case 11: turn-to-turn fault (A1–A4)

Figure 15a–d show the practical results for case 11. Case 11 is a turn-to-turn fault (A1–A4). Figure 15a plots the two voltages (v1a and v2a) of the phase A winding for the machine. Figure 15b presents the cross-coherence coefficient (Cv12a). Figure 15c manifests the algorithm tripping signal, and Fig. 15d depicts the auto-coherence coefficients (Cv1a and Cv2a). The outcomes of the phase A stator winding for the machine during the turn-to-turn fault are illustrated in Fig. 15. During the fault time, there is a noticeable difference between the two voltages (v1a and v2a), which originates a differential voltage in the relay. In this test, the values of the coherence coefficients (Cv12a, Cv1a and Cv2a) are close to one per unit, and the factor Kva≈ 0.826 that is lower than Kvpu during the fault interval. These findings assure the event of turn-to-turn fault. As a result, the fault operates the proposed algorithm. Therefore, the protection operating time is Tvop≈ 0.666 s, as included in Table 5.

Case 12: turn-to-turn fault (A1–A5)

Figure 16a–d show the experimental results for case 12. Case 12 is a turn-to-turn fault (A1–A5). Figure 16a displays the two voltages (v1a and v2a) of the phase A stator winding for the machine. Figure 16b depicts the cross-coherence estimator (Cv12a). Figure 16c illustrates the protection tripping signal, and Fig. 16d presents the auto-coherence estimators (Cv1a and Cv2a). The results of the phase A stator winding for the machine during the fault period of the turn-to-turn (A1–A5) are depicted in Fig. 16. During the fault period, there is a small difference between the two voltages (v1a and v2a), which causes a differential voltage in the protection. In this experiment, the values of the coherence estimators (Cv12a, Cv1a and Cv2a) are approximately + 0.85, + 1.0, + 0.80, respectively, and the factor Kva≈ 0.667 that is less than Kvpu = 0.95 during the fault span. These findings affirm the incidence of turn-to-turn fault. Therefore, the fault activates the proposed technique. As a result, the protection tripping time is Tvop≈ 0.236 s, as given in Table 5.

Case 13: turn-to-turn fault (A1–A7)

Figure 17a–d illustrate the experimental results for case 13. Case 13 is a turn-to-turn fault (A1–A7). Figure 17a plots the two voltages (v1a and v2a) of the phase A winding for the machine. Figure 17b presents the cross-coherence coefficient (Cv12a). Figure 17c manifests the algorithm tripping signal, and Fig. 17d depicts the auto-coherence coefficients (Cv1a and Cv2a). The outcomes of the phase A stator winding for the machine during the turn-to-turn fault are illustrated in Fig. 17. During the fault time, there is a noticeable difference between the two voltages (v1a and v2a), which originates a differential voltage in the relay. In this test, the values of the coherence estimators (Cv12a, Cv1a and Cv2a) are nearly + 0.90, + 1.0, + 0.95, respectively, and the factor Kva≈ 0.533 that is lower than Kvpu during the fault interval. These findings assure the event of turn-to-turn fault. As a result, the fault operates the proposed algorithm. Therefore, the protection operating time is Tvop≈ 0.128 s, as included in Table 5.

The experimental tests on external shunt faults, ranging from case number 14 to case number 16), will be illustrated as follows:

Case 14: external shunt fault (A5–B5)

Figure 18a–d illustrate the practical findings for case 14. Case 14 is an external shunt fault (A5–B5). Figure 18a introduces the two voltages (v1a and v2a) of the phase A stator winding for the AC machine. Figure 18b presents the cross-coherence indicator (Cv12a). Figure 18c declares the blocking signal, which its value is zero during the full display time, and Fig. 18d offers the two auto-coherence indicators (Cv1a and Cv2a). As depicted in Fig. 18, the experimental results illustrate that the state of phase A stator winding is healthy. The reason is that the two voltages signals (v1a and v2a) are nearly corresponding, and there is no difference between the two voltages. In this test, the quantified results are similar to that recorded in test 1. The values of the coherence indicators (Cv12a, Cv1a and Cv2a) are nearly 0.95. Consequently, the proposed differential voltage protection based on the coherence technique is inactive due to the external fault. As a result, the relay tripping time is infinity in this experiment.

Case 15: external shunt fault (A6–B6)

Figure 19a–d illustrate the experimental results for case 15. Case 15 is an external shunt fault (A6–B6). Figure 19a offers the two voltages (v1a and v2a) of the phase A stator winding for the induction machine. Figure 19b illustrates the cross-coherence indicator (Cv12a). Figure 19c declares the blocking signal, which its value is zero during the full display time, Fig. 19d introduces the two auto-coherence indicators (Cv1a and Cv2a). As shown in Fig. 19, the experimental results affirm that the state of phase A stator winding is normal and healthy. The cause is that the two voltages signals (v1a and v2a) are roughly identical, and there is a small difference between the two voltages. In this experiment, the obtained results are similar to that recorded in experiment 1. The values of the cross-coherence indicator (Cv12a) are about 0.96, and the values of the auto-coherence indicators (Cv1a and Cv2a) are about one. As a result, the differential voltage protection based on the coherence algorithm is blocking; leading to the protection tripping time is infinity.

Case 16: external shunt fault (A7–B7)

Figure 20a–d present the experimental results for case 16. Case 16 is an external shunt fault (A7–B7). Figure 20a depicts the two voltages (v1a and v2a) of the phase A stator winding for the machine. Figure 20b introduces the cross-coherence indicator (Cv12a). Figure 20c shows the blocking signal, which its value is zero during the full display time, Fig. 20d illustrates the two auto-coherence indicators (Cv1a and Cv2a). As shown in Fig. 20, the experimental results affirm that the state of phase A stator winding is normal and healthy. This is because the two voltages signals (v1a and v2a) are roughly identical, and there is a small difference between the two voltages. In this test, the results are similar to that recorded in test 1. The values of the cross-coherence indicator (Cv12a) are about 0.92, and the values of the auto-coherence indicators (Cv1a and Cv2a) are about one. As a result, the differential voltage protection based on the coherence algorithm is restraining; resulting in the protection operating time is infinity.

The obtained results manifest that the coherence-based differential voltage protection for the induction machine stator windings is able to:

-

(1)

Discriminate between the healthy and faulty states (healthy state is presented in case number 1, and faulty states are illustrated in cases 2–9),

-

(2)

Distinguish between the states of internal and external faults with regard to the protection zone of the machine (internal faults are depicted in cases 2–9, and external faults are shown in cases 14–16),

-

(3)

Detect the turn-to-turn faults, and estimate the tripping times in these faults (as shown in cases 10–13),

-

(4)

Develop a novel tripping-characteristic curve based on the coherence indicators calculated for machine voltage waves (as presented in Fig. 1), which is created to differentiate between turn-to-turn, external and internal shunt faults,

-

(5)

Assess the unbalance degree using the cross-coherence indicators estimated between each two phases of the three-phase voltages, and

-

(6)

Classify the shunt faults located inside the machine protection region (as illustrated in Fig. 3a,b),

For the sixteen case studies, a comparison of power quality parameters of the two measured voltages (v1a and v2a) is presented in Table 6.

Protection characteristics

Protection properties assessment

The characteristics of the present method have been assessed over a period of four months. During this span, the total number of trips in this project was 970.0, out of which 11.0 were incorrect. The total number of instances where the protection method failed to trip was 19.0. The protection was restrained 90 times without any problems when the system was operating normally. In Table 7, the quantitative findings regarding the algorithm’s properties under the influence of diverse fault types and voltage transformer errors are presented39,40.

Algorithm merits

The benefits of the coherence indicators are summarized below.

-

(1)

The data window area can be utilized to control both the protection speed and the fault detection time. The smaller the data window, the lower the protection accuracy and the faster the protection speed,

-

(2)

The association and synchrony degrees of the three-phase voltage signals can be identified and evaluated simultaneously using the coherence measure. Therefore, it is convenient to measure the severity of the unbalanced voltages,

-

(3)

A tripping curve is designed based on the coherence indicators for the voltage signals. This curve can be harnessed to trip the machine circuit breakers when the incidences of the fault or imbalance occur to avoid the system harm; while, it prevents the protection operation in the situations of voltage balance and normal operation for the machine,

-

(4)

The protection can readily set the convenient coherence threshold values to differentiate between the faulty and healthy states, as well as distinguish between the internal and external shunt faults,

-

(5)

A balance between the protection speed and accuracy can be considered because high-speed protection systems tend to be less accurate,

-

(6)

The cross-coherence indicators combine the influences of zero and negative sequence components to determine and measure the voltage asymmetry. Thereby, the coherence is considered a suitable instrument to assess the di-symmetry coefficients,

-

(7)

The protection sensitivity can be set using the data window distance and the coherence setting divergences,

-

(8)

In practice, the coherence threshold values can be adjusted by observing the alarm flag and protection response signal during normal operation, as well as the acceptable unbalance of the machine waveforms on the LABVIEW platform. As the coherence settings are closer to + 1.0, as the relay accuracy is lower,

-

(9)

To increase the computational efficiency, the measurement errors should be avoided using the following:

-

(a)

A suitable data set should be chosen to eliminate the voltage measurement errors and acceptable ripples,

-

(b)

Differential mode should be selected for the analog-to-digital converter,

-

(c)

It is important to found a proper grounding in the experimental system,

-

(d)

Anti-aliasing criterion should be used in digital signals processing,

-

(e)

The voltage transformers should be from the same manufacturer, and have the same accuracy class and VTR.

-

(a)

-

(10)

To investigate the algorithm reliability in larger-scale machines, several factors should be followed:

-

(a)

The algorithm uses two voltage waves (as analog inputs) for each phase to monitor changes in these voltages at once,

-

(b)

The experimental system should be tested under extensive and diverse fault conditions, such as turn-to-turn and shunt faults,

-

(c)

A new configuration of tripping characteristic has been set up, which can be harnessed to make the algorithm active when a fault or imbalance event happens to prevent any machine damage. Whereas, the algorithm is inactive when the machine is normal and its output voltages are balanced,

-

(d)

Accurate design, proper components, and correct installation and testing are necessary for the whole protection system to guarantee its reliability. This involves the reliability of diverse elements, such as analog input circuits, digital relays, and the digital output circuits.

-

(e)

Duplicating the algorithms or two analog input signals to the protection system can attain the protection reliability,

-

(f)

To verify the efficient and effective protection algorithm, a variety of tests should be conducted, including but not limited to:

-

(I)

Simulation testing The machine behaviors under diverse fault scenarios have been simulated utilizing the ATP program, and the MATLAB program has been exploited to process the protection algorithm. The simulation testing can verify the coherence settings and logic of the algorithm. However, the simulation examination faces certain obstacles, like the model accuracy, the difficulty of simulated complex faults, and the running time required for the simulation.

-

(II)

Primary injection testing The protection algorithm has been verified through primary injection testing, which has been conducted by injecting voltage signals into the protection system and measuring the protection response. This test necessitates eventually a personal computer, an analog-to-digital converter, and LABVIEW software. The primary injection testing can confirm the functionality, sensitivity, and accuracy of the protection system under actual situations, as well as its performance. Nonetheless, the primary injection testing faces several obstacles, such as the safety of the participants and the availability of large-scale machines.

-

(I)

-

(a)

-

(11)

The coherence settings can be exploited to control the restraining and operating regions contained within the tripping characteristic curve of the protection. The subsequent points demonstrate their impact on the protection characteristics:

-

(a)

An increase in both the data set area and the blocking region located within the tripping characteristics can boost the protection security,

-

(b)

Reducing both the data set area and the blocking region located within the tripping characteristics can increase the protection sensitivity.

-

(c)

The application of the data set principle to measure the coherence indicators filters the input waves and delays the protection operation. This verifies that the protection is stable, leading the system to continue to be stable under the following conditions: VT measurement errors, acceptable harmonics, and transient faults,

-

(d)

The algorithm is highly reliable because of its immunity to various fault types, fault onset times, fault time intervals, and fault locations. It can also identify the vast majority of fault types,

-

(e)

The technique satisfies the protection’s reliability and stability. The protection’s reliability is mainly measured by the absence of failures in the relay operation, while the protection’s stability is determined by the protection’s efficiency for recognizing system operating conditions,

-

(f)

A compromise in the protection settings is essential to coordinate between dependability and stability, accuracy and speed, and sensitivity and security. Therefore, the values of the coherence settings selected are 0.05, and the data set area is taken as a single cycle in the proposal.

-

(a)

Comparative assessment of the suggested scheme

Table 8 presents a crucial comparison between the suggested coherence-based differential voltage protection and other recent approaches in terms of performance metrics (such as main concept, functional role, configuration of tripping curve, protection accuracy, computation time, protection settings, and asymmetry ratios).

Algorithm assumptions

To stratify this approach in large-scale or more complicated systems, several assumptions must be considered, as listed below.

-

(1)

Certain common requirements should be satisfied for the voltage transformers and their measurements, as follows:

-

(a)

Voltage transformers are the same transformer type used in three-phase circuits,

-

(b)

Voltage transformers have the same accuracy class,

-

(c)

Voltage transformers have the same ratio of turns, and are the same size, and.

-

(d)

Voltage measurements should be perfectly synchronized.

-

(a)

-

(2)

The coherence-based protection algorithm requires the following:

-

(a)

A large sample quantity can yield statistically significant findings, even if the coefficient of coherence is small. Thus, a significant sample size should be considered, and.

-

(b)

The coherence estimator lacks sensitivity to the transformation and scale, so the algorithm has not responded to several fault cases.

-

(a)

-

(3)

To relieve the incidence of unsound tripping of the algorithm, arising from power quality troubles, certain provisions should be taken, including the following:

-

(a)

The data set and coherence settings should be reasonable,

-

(b)

The analog-to-digital converter should be set to work in differential mode,

-

(c)

It is imperative to establish a proper grounding system within the practical system,

-

(d)

Proper instrument transformers with the same type, rating, accuracy class, and ratio of turns should be considered,

-

(e)

Digital sensors, meters, and LABVIEW software, should be used to take measurements of electrical signals and record continuously the parameters of the power quality,

-

(f)

The antialiasing principle and the Nyquist sampling theorem should be applied.

-

(a)

Contributions

A list of contributions from the authors is presented below.

-

(1)

A new coherence-based method of differential voltage protection for induction machine stator windings is proposed. Only three-phase voltages are acquired at the two terminals of the stator windings of the AC machines to process the differential protection,

-

(2)

A new connection circuit for the differential voltage relay has been established between the mid and full points of each winding, which can be used to protect the entire windings of power transformers, synchronous machines, and induction machines. This design can protect single-phase and three-phase machines, as well as the equipment with single or dual windings per phase,

-

(3)

To discriminate between the instances of turn-to-turn faults, and external and internal faults, a novel design of quadratic operating characteristic curves based on the coherence instrument is presented.

-

(4)

The shunt faults existing within the AC machine protection zone can be immediately identified and classified using the cross-coherence indicators. Furthermore, a novel mathematical model can be used to quantify the relay operating time in the instance of turn-to-turn faults, and.

-

(5)

The intensity degree of imbalance and fault for the three-phase voltages can be specified and evaluated utilizing the cross-coherence and auto-coherence indicators, respectively.

Conclusions

A coherence-based differential voltage protection for the machine stator windings protection has been proposed. To process the proposed algorithm, three-phase voltages have been measured at the midpoint and complete end of each stator winding of the machine. The voltage waveforms have been measured with the DAC, and the algorithm has been run in LABVIEW software. The methodology has been tested on a three-phase induction machine that contains 20 taps for each phase stator winding. This configuration is designed to install voltage transducers at the center points and the full terminals of the three-phase stator windings, and to facilitate thorough examinations to assess the algorithm’s effectiveness and efficiency. Various fault incidences have been investigated, such as winding-to-neutral, winding-to-winding, and turn-to-turn faults. The testing results have shown that the algorithm security and dependability rates are greater than 98%, and the algorithm reliability and accuracy rates are about 97.0%. Actually, the differential voltage protection has the capability to detect a fault occurrence, define turn-to-turn faults, and distinguish shunt faults inside and outside the machine zone. It can also classify ten types of shunt faults in the machine protection zone. The quantitative findings have demonstrated that the response time for detecting the internal shunt fault has been achieved within 20 ms, indicating an immediate response for the relay. Whereas, in the event of the turn-to-turn fault, the operating time has been contingent upon its severity level, which has been estimated using a novel mathematical expression. Besides, a new form of relay operating curves, based on the coherence indicators, has been founded to contrast turn-to-turn faults, external and internal faults. Moreover, the approach can assess the ferocity grade of the three-phase voltages imbalance and troubles, and it can protect single-phase and three-phase windings of various AC machines, as well as power transformers. It can be applied to protect the AC machines with single or dual windings per phase as well. Furthermore, the protection sensitivity, security, dependability, and fault detection time can be controlled by modifying coherence settings and data window size.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Yang, Y., Chen, Y. & Hao, W. Online detection of inter-turn short-circuit fault in dual-redundancy permanent magnet synchronous motor. IET Electr. Power Appl. 15, 104–113 (2021).

Abdallah, H. & Benatman, K. Stator winding inter-turn short-circuit detection in induction motors by parameter identification. IET Electr. Power Appl. 11(2), 272–288 (2017).

Wang, B., Shen, C., Kexing, Xu. & Zheng, T. ‘Turn-to-turn short circuit of motor stator fault diagnosis in continuous state based on deep auto-encoder’. IET Electric Power Appl. 13(10), 1598–1606 (2019).

Faiz, J., Nejadi-Koti, H. & Valipour, Z. Comprehensive review on inter-turn fault indexes in permanent magnet motors. IET Electr. Power Appl. 11(1), 142–156 (2017).

Mostafaei, M. & Faiz, J. An overview of various faults detection methods in synchronous generators. IET Electr. Power Appl. 15, 391–404 (2021).

Afshar, M., Abdi, S., Oraee, A., Ebrahimi, M. & McMahon, R. Eccentricity fault detection in brushless doubly fed induction machines. IET Electr. Power Appl. 15, 916–930 (2021).

Deekshit Kompella, K. C., Rongala, N. S., Rayapudi, S. R. & Mannam, V. G. R. Robustification of fault detection algorithm in a three-phase induction motor using MCSA for various single and multiple faults. IET Electr. Power Appl. 15, 593–615 (2021).

Otero, M., de la Barrera, P. M., Bossio, G. R. & Leidhold, R. ‘Stator inter-turn faults diagnosis in induction motors using zero-sequence signal injection’. IET Electric Power Appl. 14(14), 2731–2738 (2020).

Faiz, J. et al. Diagnosis of inter-turn fault in stator winding of turbo generator. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 29(12), e12132 (2019).

Dehghan, H., Haghjoo, F. & Cruz, S. M. A flux-based differential technique for turn-to-turn fault detection and defective region identification in line-connected and inverter-fed induction motors. IEEE Trans. Energy Conv. 33(4), 1876–1885 (2018).

Mirzaeva, G. & Saad, K. I. Advanced diagnosis of stator turn-to-turn faults and static eccentricity in induction motors based on internal flux measurement. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 54(4), 3961–3970 (2018).

Pinto, P. S., Dinis, H. S., Cardoso, A. J. M. & Vasconcelos, H. C. Fault detection in induction motors using convolutional neural networks and motor current signature analysis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 17(3), 1885–1894 (2021).

Xu, Y., Zhang, S. & Gao, W. A Hybrid approach for fault diagnosis of induction motors using machine learning and wavelet transform. IEEE Access 9, 37179–37188 (2021).

Liu, X., Li, Z. & Huang, J. Transfer learning with few-shot learning for induction motor fault diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 18(2), 1090–1099 (2022).

Yang, B., Sun, Y. & Wang, H. Ensemble deep learning models for fault diagnosis of induction motors. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 57(6), 6635–6644 (2021).

Jiang, H., Li, C. & Wang, Y. Wavelet packet decomposition and machine learning for fault diagnosis of induction motors. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 68(9), 7856–7865 (2021).

Lin, Y., Yang, S. & Chen, G. Edge computing for real-time fault diagnosis of induction motors. IEEE Access 10, 20135–20145 (2022).

Zhao, J., Sun, Y. & Li, Z. Hybrid CNN-RNN model for fault diagnosis of induction motors. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 68(11), 11234–11244 (2021).

Feng, G., Lai, C. & Kar, N. C. An analytical solution to optimal stator current design for PMSM torque ripple minimization with minimal machine losses. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 64(10), 7655–7665 (2017).

Park, J. K. & Hur, J. Detection of inter-turn and dynamic eccentricity faults using stator current frequency pattern IPM-type BLDC motors. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 63(3), 1771–1780 (2016).

Qi, Y., Bostanci, E. & Akin, B. Severity estimation of inter-turn short circuit fault for PMSM. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 66(9), 7260–7269 (2019).

Du, B. et al. Inter-turn fault diagnosis strategy for interior permanent-magnet synchronous motor of electric vehicles based on digital signal processor. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 63(3), 1694–1706 (2016).

Chen, Y., Chen, Y. & Shen, Y. On-line detection of coil inter-turn short circuit faults in dual-redundancy permanent magnet synchronous motors. Energies 11(3), 662 (2018).

Chen, Y. et al. Online diagnosis of inter-turn short circuit for dual-redundancy permanent magnet synchronous motor based on reactive power difference. Energies 12(3), 510 (2019).

Ghanbari, T. Autocorrelation function-based technique for stator turn-fault detection of induction motor. IET Sci. Meas. Technol. 10(2), 100–110 (2016).

Zhang, H., Sun, J., Hou, K., Li, Q. & Liu, H. Improved information entropy weighted vague support vector machine method for transformer fault diagnosis. High Voltage 7, 510–522 (2022).

Peng, S., Sujie, G. & Xiuli, W. Real-time condition Assessment of power transformers based on time-effect score function and Bayesian probability. High Volt Eng. 44(04), 35–43 (2018).

Huang, X. B. et al. Transformer fault prediction based on time series and support vector machine. High Volt. Eng. 46(7), 2530–2538 (2020).

Islam, M., Lee, G. & Hettiwatte, S. N. Application of Parzen window estimation for incipient fault diagnosis in power transformers. High Volt. Eng. 3(4), 303–309 (2018).

Tian, Y., Zhang, D., Li, X. & Zhang, X. Intelligent fault detection for induction motors using a CNN-LSTM model. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Measurement 71, 1–10 (2022).

Tun, P. P., et al. Brushless synchronous generator turn‐to‐turn short circuit fault detection using multilayer neural network. In Asian Conference on Energy, Power and Transportation Electrification (ACEPT), pp. 1–8 (2018).

López-Pérez, D. & Antonino-Daviu, J. Application of infrared their mography to failure detection in industrial induction motors: Case stories. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 53(3), 1901–1908 (2017).

Reimert, D. Protective Relaying for Power Generation Systems (Taylor & Francis Group, 2017).

Ghanbari, T., Samet, H. & Ghafourifard, J. New approach to improve sensitivity of differential and restricted earth fault protections for industrial transformers. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 10(6), 1486–1494 (2016).

Shah, A. M., Bhalja, B. R. & Patel, R. M. New protection scheme for power transformer based on superimposed differential current. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 12(14), 3587–3595 (2018).

Davarpanah, M., Sanaye-Pasand, M. & Iravan, R. Performance enhancement of the transformer restricted earth fault relay. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 28(1), 467–474 (2013).

Esponda Hernandez, H., Vázquez Martínez, E. & Andrade Soto, M. A. Differential protection in power transformers using the statistical second central moment. J. Eng. 2018(15), 1330–1334 (2018).

Platero, C. A. et al. Scheme for synchronous machine stator turn-to-turn protection. IET Electr. Power Appl. 14(4), 716–722 (2019).

Mahmoud, R. A. & Elwakil, E. S. Experimental investigations using quadratic-tripping characteristics based on alienation/coherence coefficients of voltage and current signals for synchronous generators protection. IET Gener. Transmiss. Distrib. 15(21), 2978–3000 (2021).

Mahmoud, R. A. Experimental performance verification of an intelligent detection and assessment scheme for disturbances and imbalances of three-phase synchronous machine output using coherence estimators. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76343-8 (2024).

Mahmoud, R. A. & Emam, A. Coherence-based automatic power factor correction (APFC) algorithm for power grids. IET J. Eng. 2022(5), 512–527 (2022).

Mahmoud, R. A. Smart automatic synchronization system based on coherence algorithm for power grids. IET J. Eng. 2023(1), e12214 (2023).

Mahmoud, R. A. Integrated busbar protection scheme utilizing a numerical technique based on coherence method. IET J. Eng. 2022(1), 94–119 (2022).

Mahmoud, R. A. Coherence-based integrated detection and assessment algorithm for voltages and currents unbalance/disturbance in three-phase synchronous generators: A validation of simulation results. IET J. Eng. 2023(5), e12272 (2023).

Dekhandji, F. Z., Refoufi, L. & Bentarzi, H. Quantitative assessment of three phase supply voltage unbalance effects on induction motors. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 8(S1), 393–406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13198-015-0401-3 (2017).

Milanović, J. V., Abdelrahman, S. & Liao, H. Compound index for power quality evaluation and benchmarking. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 12(19), 4269–4275 (2018).

Chiccoa, G. et al. Assessment of unbalance and distortion components in three-phase systems with harmonics and interharmonics. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 147, 201–212 (2017).

Acknowledgements

Assoc. Professor/ Ragab Abd Allah Was Born in Giza, Egypt, In 1976. He Received the B.Sc. Degree in Electrical Machine & Power Engineering from Cairo University, Faculty of Engineering, Egypt, In 2001; and The M.Sc. and Ph.D. Degrees in Electrical Machine & Power from Helwan University, Faculty of Engineering, Department of Electrical Machines& Power Engineering, Cairo, Egypt, In 2007 And 2012, Respectively. I Addition to That I Possess Associate Professor Certificate. M.Sc. Thesis Under the Following Title: ‘‘ A Digital Busbar Protection Scheme Avoiding Current Transformer Saturation Effects’’; And Ph. D. Thesis Under the Following Title: ‘‘Multifunction Digital Relay for Large Synchronous Generators Protection’’. Assoc. Professor/ Ragab Abd Allah Is a Chairman of Electrical Power and Control Department in Pyramids Higher Institute for Engineering and Technology-Electrical Power and Control Department- 6th of October City-Giza-Egypt. He Is a Live Member of the Quality Committee of Electrical Power Engineering Department in the Institute. His Current Research Interests Include Power System Protection and Automation, Power System Operation and Control, Renewable Energy, Smart Grids (SG), And Power Quality. This project has been undertaken in the electrical power laboratory at Misr University for Science and Technology (MUST) in Egypt. I would like to thank the students of the Bachelor of Electrical Power and Machines Engineering graduation project, which I supervised, for designing and building the practical model on which the proposed method was tested.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R. A. Mahmoud: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Data curation, Writing-Original draft preparation, Visualization, Investigation, Supervision, Validation, Writing-Reviewing and Editing,

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahmoud, R.A. Experimental evaluation of differential voltage protection scheme based on a coherence function applied to AC machine stator windings. Sci Rep 15, 12399 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93210-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93210-2