Abstract

A heart murmur is an atypical sound produced by blood flow through the heart. It can indicate a serious heart condition, so detecting heart murmurs is critical for identifying and managing cardiovascular diseases. However, current methods for identifying murmurous heart sounds do not fully utilize the valuable insights that can be gained by exploring different properties of heart sound signals. To address this issue, this study proposes a new discriminatory set of multiscale features based on the scaling and complexity properties of heart sounds, as characterized in the wavelet domain. Scaling properties are characterized by examining fractal behaviors, while complexity is explored by calculating wavelet entropy. We evaluated the diagnostic performance of these proposed features for detecting murmurs using a set of classifiers. When applied to a publicly available heart sound dataset, our proposed wavelet-based multiscale features achieved 76.61% accuracy using support vector machine classifier, demonstrating competitive performance with existing deep learning methods while requiring significantly fewer features. This suggests that scaling nature and complexity properties in heart sounds could be potential biomarkers for improving the accuracy of murmur detection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is one of the leading causes of death on the globe, accounting for 16% of total deaths from all causes1. Cardiac auscultation, listening to the heart with a stethoscope, is a popular cost-effective screening method that helps in identifying murmurous heart sounds potentially indicative of CVDs2. A heart murmur is an extra swooshing sound that is produced by turbulent blood flow through the heart and is discernible from heartbeat sounds. When listening to the heart, healthcare professionals consider several factors, such as volume, location, pitch, timing of the murmur, and sound changes to tell if a murmur is harmful and a sign of cardiac health problems. Thus, cardiac auscultation can filter out patients without heart disease or defects by identifying the presence of heart murmurs3.

Identifying and interpreting cardiac murmurs by auscultation can be challenging even for expert cardiologists. To overcome these challenges, efforts have been made over the past few years to improve heart murmur detection through more objective methods. Deep learning (DL)-based artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms have been popular for heart murmur studies4,5,6,7,8,9,10. This is due to their ability to perform well with numerous features and to overcome the challenges of feature selection while achieving an accuracy that is similar to that of expert cardiologists11,12. However, concerns have been raised regarding DL model complexity, interpretability, and black-box characteristics, which hinder understanding of how they work. This in turn may pose challenges, particularly for healthcare professionals for making timely interventions13.

Models based on multi-domain features, such as time, frequency, and time-frequency domains, have also been proposed for effective murmured detection. In this regard, wavelet transforms-based methods have been frequently proposed in particular14,15. That is because, unlike Fourier transforms, wavelets shift the time-domain data to a space localized in both time and frequency, thus enabling the analysis of cardiac signals at different times and scales (i.e., resolutions) and unveiling their hidden patterns. For instance, according to16, the discrete wavelet transform (DWT) is better at filtering heart murmur sounds without affecting different sound patterns that occur in heart sounds. The study in17 also reports that wavelet-based techniques can achieve better performance in phonocardiogram analysis, compared to time-domain techniques.

It has been demonstrated that integrating multi-domain features into DL models can minimize the impact of challenges associated with DL models while improving murmur detection capabilities9,18. Incorporating wavelets-based methods with DL has also been a popular approach. The role of WT in these methods can primarily be seen either in the form of data pre-processing or feature engineering. For instance, in a more recent study19, used wavelet scattering transforms and 1-D convolution NNs (CNNs) to detect heart murmurs from phonocardiogram recordings. The wavelet scattering transforms are used here for performing several pre-processing steps, such as denoising, segmentation, re-labeling of noise-only segments, data normalization, and time-frequency analysis of the phonocardiogram segments. On the other hand, authors in20 adopted features acquired from DWT in DL, achieving strong model performance. Since the use of features extracted using WT does not always help achieve greater performance, some studies attempt to jointly use multi-domain features, such as time and time-frequency for detecting murmur14,15. However, the existing studies overlook the true potential of only wavelet-based multiscale features such as scaling behavior, long memory, and fractality, in identifying murmurous heart signals although these features have shown promising performance in various disease diagnosis applications21,22. In summary, to the best of our knowledge, no attempts have been made to explore the true potential of wavelet transforms in analyzing heart sound signals for murmur detection in particular. This gap therefore motivated to explore the possibility of detecting murmurous heart sounds exclusively through wavelet analysis.

The main contribution of this study is therefore to propose a set of novel features based solely on wavelet transforms for detecting heart murmurs. More specifically, these features are primarily based on two multi-scale properties: the scaling nature and complexity of heart sound signals characterized in the wavelet domain. Scaling nature is characterized by the presence of stochastic similarity at different scales, which can be either monofractal or multifractal. Monofractal processes can be characterized using a single irregularity index (i.e. Hurst exponent), but more complex natural processes require a distribution of irregularity indices. Therefore, this study assesses scaling nature, considering both monofractal and multifractal properties in heart sound signals. The complexity of heart sound signals is assessed by computing the entropy across different scales.

First, the analysis of monofractal properties of heart sounds usually involves assessing the scaling behavior of signals at different resolutions in the wavelet domain by using wavelet spectra. This approach characterizes the level-wise decay in scale-specific average energies of the wavelet coefficients obtained from the wavelet decomposition. The term “energy” used here is an engineering term for the magnitude of squared wavelet coefficients. The rate of this energy decay along increasing scales (i.e., decreasing resolutions) is used as a discriminatory feature to quantify the degree of self-similarity ( or irregularity) in heart sound. Additionally, the normalized level-wise energies are used to compute wavelet entropy, which characterizes complexity (or energy disbalance) in the signal. In this study, we use a rolling window-based approach to quantify self-similarity and entropy, which allows for exploring localized irregularity and complexity in heart sound. This approach enables the analysis of variability in irregularity and complexity across each signals and is more effective than relying on a single irregularity index and entropy.

Second, to assess multifractality in heart sound signals, a multifractal spectrum is computed in the wavelet domain and then its properties are explored. The multifractal spectrum is a function that describes the distribution of fractal dimensions across different scales of the system. To construct the spectrum, local irregularity index is calculated at each point in the signal, and the distribution of these irregularity indexes across scales is measured. The multifractal spectrum can provide valuable insights into the complex behavior of the signal, enabling the extraction of additional features to characterize hidden signal dynamics that are not possible with the spectra computed for monofractal processes. The degree of deviation from monofractality can be determined by exploring features such as broadness, left slope, and left tangent, which will be described in the sequel.

Finally, we evaluate the potential of these multiscale features for detecting murmurs in the heart using different classifiers, including Logistic Regression (LR), K-nearest neighbor (KNN), support vector machine (SVM), and neural network (NN), by reporting their sensitivity, specificity, and classification accuracy.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section “Motivation study” gives an overview of the motivating study and datasets used for the analysis. The techniques used in this study, fundamentals of wavelet transform, and assessment of monofractal and multifractal properties by using wavelet transforms, are presented in “Methodology”. Sections “Data analysis” and “Results” provide data analysis procedures and results, respectively. Section “Discussion” which discusses the results is followed by some concluding remarks in “Conclusions”.

Motivation study

(a) Locations of the heart sound recordings: Pulmonary Valve (PV), Tricuspid Valve (TV), Aortic Valve (AV), and Mitral Valve (MV); 1 = right second intercostal space; 2 = left second intercostal space; 3 = mid-left sternal border (tricuspid); 4 = fifth intercostal space, midclavicular line (the image is taken from23) and (b) a sample heart sound recording at Mitral Valve (MV) point.

Dataset

This study analyzes CirCor DigiScope dataset from Physionet 202224. The dataset was gathered in two cardiac screening campaigns on participants from rural and urban areas in Northeast Brazil. A total of 5282 heart sound recordings were collected from the main four auscultation locations of 1568 patients, 70% of which are publicly released. Out of the total 1568 patients, 1144 (73%) were normal subjects and 305 (19.5%) were with heart murmurs. The four auscultation locations are Pulmonary Valve (PV), Tricuspid Valve (TV), Aortic Valve (AV), and Mitral Valve (MV) (see Fig. 1). The “Caravan of the Heart” campaign, the data collector, gathered heart sounds with DigiScope collector technology and saved as phonocardiogram (PCG) signals. These signals have a duration between 4.8 to 80.4 seconds with a mean of 22.9 and a standard deviation of 7.4 in units of a second. The sound signals were sampled at 4 kHz with 16-bit resolution and normalized to the range between − 1 and 1.

The dataset was manually annotated by an expert annotator. Signals of 119 (7.6%) patients were inconclusive for murmur detection due to poor audio quality. The patients were aged between 0.1 and 356.1 months with a mean of 73.4 and a standard deviation of 50.3 in units of a month. Additionally, socio-demographic and clinical variables, such as age, gender, weight, and height along with murmur location, pregnancy status, and type of murmur (systolic or diastolic) of each patient were also compiled into a spreadsheet, where all entries were examined for data quality assessment.

Related works

In addition to the CirCor DigiScope dataset, there are several publicly available heart sound datasets for the detection of different cardiovascular diseases, including murmurs, as described in23. Two of the datasets that have been used heavily for heart murmur detection are PASCAL CHSC 2011 and PhysioNet2016. These datasets, including those that are not publicly available, have led to the development of several computer-aided approaches for detecting heart murmurs. These approaches commonly based on DL methods or feature extraction methods, or their combined versions.

Deep learning (DL) algorithms are a popular choice as they have demonstrated precision comparable to experienced cardiologists in heart sound classification11,25. For example, in a study using the CirCor DigiScope dataset9, patient recordings were segmented into log-mel spectrograms, which were classified using the Dual Bayesian ResNet (DBRes) model. Integrating DBRes with demographic data and signal features via XGBoost improved accuracy from 0.762 to 0.820. Detecting murmurs in children is particularly challenging due to the prevalence of benign murmurs, but a NN-based method25 achieved 100% sensitivity and specificity in pediatric murmur detection. Similarly, transfer learning with ResNet50 yielded 87.65% accuracy for heart murmur detection7, and another NN method using energy spectrum analysis reached 83% sensitivity and 90% specificity26. In addition, DL models like CNNs and RNNs have shown promise for murmur detection, with sensitivity and specificity rates of 76.3% and 91.4%, respectively27.

Feature extraction methods have also been proposed for murmur detection, including Fourier and wavelet transforms. A method using short-time Fourier transform for heart sound segmentation achieved 93% sensitivity28. Another study18 employed power spectrum estimation, wavelet transform, and Mel frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs) to extract characteristics of PCG signals, then used classifiers like SVM and KNN for classification. A wavelet-based method that measures signal simplicity and adaptively thresholds to discriminate between normal heart sounds and murmurs reached 89.10% sensitivity and 95.50% specificity12. Additionally, wavelet-based feature extraction combined with NN and SVM classifiers demonstrated 89% sensitivity, 85% specificity, and 87% accuracy in distinguishing murmurs in children29.

Overall, the published literature demonstrates the potential of DL and feature extraction methods to serve as accurate and reliable diagnostic tools for heart murmur screening, reducing the reliance on more expensive and invasive diagnostic techniques. However, a systematic review, particularly focused on DL-based attempts, emphasizes the need for robust models and sufficient data to overcome existing limitations such as insufficient data, inefficient training, and model availability, in heart sound classification30. Also, improvements are still needed to address challenges in feature extraction methods, such as signal segmentation accuracy, feature selection, and interpretations.

This study also aims to develop a more interpretable feature set based on scaling features and simple models, enabling effective murmur detection, and overcoming challenges of the existing models. Hence, the present study shares similarities with existing research in feature extraction from the time and time-frequency domains, as well as in classification methods. However, the key distinction lies in the proposed method’s emphasis on features extracted from the time-frequency (multiscale or wavelet) domain, specifically focusing on the scaling properties of heart sound signals. While deep learning (DL)-based models, such as those in9,26, also utilize time and time-frequency domain features and demonstrate high performance, they face challenges, particularly the need for a large number of features (i.e., higher model complexity) and limited interpretability of the features used in DL models.

In addition, considering the studies that have proposed wavelet-based feature extraction methods12,29, the key difference in this study is that the extracted features are based exclusively on the scaling nature of heart sounds. Some studies, for instance in9,18, have considered scaling properties using wavelet and Fourier transform techniques, but they primarily focus on monofractal properties, which are limited in capturing heart sound dynamics. In contrast, this study incorporates both monofractal and multifractal properties to better differentiate between normal and murmurous heart sounds.

Methodology

This section introduces the techniques used to extract multiscale features by assessing scaling properties of heart sound signals in the wavelet domain. First, we provide a brief overview of wavelet transforms. Then, we describe how the scaling properties are assessed by using the monofractal and multifractal spectra. Supplementary information (SI - S1–S4) provides technical details about these techniques.

Discrete wavelet transform

Wavelet transforms (WTs) are widely used tools in signal processing. When applied to a signal, they decompose the signal into a set of localized contributions in both the time and frequency domains, producing a hierarchical representation. This representation allows for simultaneous analysis at different resolutions or scales, making it possible to explore signal properties that may not be apparent in the domain of original data (acquisition domain).

The discrete wavelet transform (DWT), a popular version of WTs, has emerged as an important tool for analyzing complex data signals in application domains where discrete data are analyzed. DWTs are linear transforms that can be represented by orthogonal matrices. That is, DWT decomposes a signal \(Y\) of size \(N \times 1\) into wavelet coefficients using an orthogonal matrix \(W\), such that \(d = WY\). The matrix \(W\) is determined by the chosen wavelet basis, such as Haar, Daubechies, or Symmlet. To facilitate efficient computation, \(N\) is typically set as a power of two, i.e., \(N = 2^J\), where \(J\) is a positive integer. The computational cost of performing the DWT in matrix form increases with increasing signal length.

A fast algorithm based on filtering proposed by Mallat is used for computational efficiency31. The DWT with this algorithm is obtained by performing a series of successive convolutions that involve a wavelet-specific low-pass filter and its mirror counterpart, high-pass filter. These repeated convolutions using the two filters accompanied with the operation of decimation (keeping every second coefficient of the convolution) generate a multiresolution representation of a signal, consisting of a smooth approximation and a hierarchy of detail coefficients at different resolutions (or scale indexes) and different locations within the same resolution. Mathematically, \(c_{J_0}\) represents the smooth trend, and \(\begin{array}{c} d \\ \sim \end{array}_j\) are detail coefficients at different resolutions. The decomposition continues until a chosen level \(J_0\), where \(1 \le J_0 \le J-1\). Finally, the transformed signal is structured as \(d = (c_{J_0}, \begin{array}{c} d \\ \sim \end{array}_{J_0}, \dots , \begin{array}{c} d \\ \sim \end{array}_{J-2}, \begin{array}{c} d \\ \sim \end{array}_{J-1})\). Technical details for computing these coefficients can be found under S1 in SI and detailed information can be in32.

These coefficients describe the signal at different resolutions (scales) and locations, and are used to characterize multi-scale features in the signal.

Extraction of multiscale features

Fractality is an intriguing property observed in processes that exhibit self-similar behavior, which is defined by the presence of stochastic similarity at different scales. Natural processes typically exhibit fractality in one of two forms: monofractal or multifractal. A growing body of research demonstrates that wavelets-based methods are particularly effective for analyzing fractality33.

Monofractality-based features (slope)

Monofractality is the property of a signal where the scaling properties remain regular across the scales. This is often observed in signals that have a simple and regular structure, and in such cases, the scaling properties are uniform across all scales, and the system exhibits a single fractal dimension. In general, analysis of monofractality is useful in the study of complex systems because it provides a reference point for comparison with multifractal systems.

Wavelet transform-based methods have been proven to be suitable for modeling monofractal processes. More specifically, wavelet spectrum is usually used to characterize scaling behavior of the signal. The wavelet spectrum is formed by taking the log average of squared detail wavelet coefficients, which are also referred to as log energies, at different scales. Mathematically, given the wavelet detail coefficients at level \(j\), denoted as \(\begin{array}{c} d \\ \sim \end{array}_j = \{d_{1}, d_{2}, \dots , d_{n}\}\), the wavelet spectrum of \(Y\) is computed as \(S(j) = \log _2\left( \overline{\begin{array}{c} d \\ \sim \end{array}_j^2}\right)\) for \(J_0 \le j \le J-1\), where \(\overline{\begin{array}{c} d \\ \sim \end{array}_j^2} = \frac{1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^n d_i^2\) represents the average of squared wavelet coefficients (also known as wavelet energy) at level \(j\). Here, \(J = \log _2(N)\) and \(J_0\) (\(1 \le J_0 \le J-1\)) is the coarsest level used to define the wavelet spectrum.

Signals which possess scaling behavior (or self-similarity) exhibit a particular behavior in their wavelet spectra such that the log energies decay linearly as resolution decreases or scale increases (see Fig. 2a). The rate of this energy decay (slope), which is usually estimated by regressing the log energies (S) on the scale indices (\(j\)), characterizes the degree of regularity. This is usually expressed by the Hurst exponent, H such that \(H = (slope +1)/2\), but this study uses the slope. Larger slopes (\(> -2\)) indicate a higher degree of persistence, and smaller slopes (\(< -2\)) indicate a higher degree of anti-persistency and intermittency. The standard Brownian motion has a log spectrum with a slope of -233. Technical details on monofractality and computing the standard wavelet spectra can be found in S2 and S3 in SI.

(a) A sample monofractal wavelet spectra. Slope of the wavelet spectra is estimated by fitting a straight line (green dashed) on the log energy of the wavelet coefficients (black) within the scale index ranging from 1 to 10 (red line). The coordinate of the point at the level j is \(\log _2 \bar{d_j^2}\), where \(d_j\) is the wavelet coefficients at the scale index j (see S1 in SI for more details on wavelet coefficients \(d_j\)) and (b) multifractal spectrum and its geometric descriptors; x-axis represents the irregularity index (H), \(\alpha (q)\) and y-axis represents values proportional to the relative frequency of H, \(f(\alpha (q))\).

Wavelet entropy

Wavelet entropy (WE) is commonly utilized as a natural indicator of the compressibility or complexity of signals. The complexity of a signal, which is generated by a random process, can vary depending on the underlying mechanism of randomness. For instance, if the signal is generated through a Gaussian iid process, it possesses the maximum entropy among all random generation mechanisms with a fixed mean and finite variance, indicating that the signal is not easily compressible. Furthermore, a standard Gaussian signal in the time domain corresponds to a standard Gaussian signal in the wavelet domain, where all level-wise wavelet entropies are theoretically identical. However, when a signal’s generating mechanism deviates from a Gaussian distribution, the level-wise entropies in its wavelet representation can provide valuable information. In extreme cases, an ordered signal, such as a sinusoidal signal, exhibits a narrow peak in the wavelet domain, resulting in low entropy. Overall, wavelet entropy quantifies the complexity of the signal, with lower values indicating greater disbalance in signal energy and low complexity. For more in-depth information regarding the wavelet entropy of signals, please refer to34.

In the present study, the normalized Shannon entropy of detail wavelet coefficients is used to compute the WE as \(WE = -\sum _{i} p_i \log p_i\), where \(p_i = \frac{d^2_i}{\sum _{j = 1}^n d^2_j}\). Here, \(d_i\) represents the wavelet coefficients at the \(J_0\)th multiresolution level, and \(n\) is the number of wavelet coefficients in that level.

Multifractality-based features

Unlike monofractal signals, multifractality of a signal means that its structure has different scaling properties at different scales. The multifractal spectrum is frequently employed as a powerful tool for examining multifractal properties. It represents the relative degree of richness of various irregularity indices. More precisely, the multifractal spectrum is constructed by calculating the local singularity strength or the Hurst exponent at each point in the signal, and then measuring the distribution of these values across different scales.

A practical approach to compute multifractal spectrum makes use of the theory of large deviations, where f would be interpreted as the rate function in a Large Deviation Principle( f measures how frequently (in k) the observed \((-1/j)\log _2|d_{j,k}|\) deviate from the expected value for \(\alpha\) in scales defined by j), where \(\alpha (t) = \lim _{k2^j \rightarrow t} \left( -\frac{1}{j} \log _2|d_{j,k}|\right)\), \(d_{k,j}\) is the normalized wavelet coefficient corresponding to the basis that is \(L_1\) normalized, that is \(\phi _{jk}(t) = 2^j\phi (2^jt - k)\) and \(\psi _{jk}(t) = 2^j\psi (2^jt - k)\) at scale j and location k.

Rather than treating multifractal spectra as functions, they can be effectively characterized using meaningful descriptors (see Fig. 2b):

-

Spectral Mode: Represents the most frequent scaling index in the spectrum. For monofractal signals, the spectral mode coincides with the Hurst exponent (\(H\)).

-

Broadness: Also known as bandwidth, broadness quantifies the range of scaling exponents and is computed as \(B = |\alpha _1 - \alpha _2|\), where \(\alpha _1\) and \(\alpha _2\) are the scaling indices satisfying \(f(\alpha _1) = f(\alpha _2) = a\). The parameter \(a\) is typically set to \(-0.2\). A larger broadness indicates a wider range of scaling exponents, signifying a greater deviation from monofractality.

-

Left Tangent (Right) Tangent, Slope, and Point: The left and right tangent-based descriptors represent the slopes of the tangents to the multifractal spectrum at specific points: \(\text {Left Tangent (LT)} = \frac{df}{d\alpha } \Big |_{\alpha _1}\) and \(\text {Right Tangent (RT)} = \frac{df}{d\alpha } \Big |_{\alpha _2}\). The LT is evaluated at \((\alpha _1, f(\alpha _1))\), while the RT is evaluated at \((\alpha _2, f(\alpha _2))\). These measures indicate deviation from monofractality, where a lower left tangent slope suggests increased multifractality. In contrast, a purely monofractal process theoretically exhibits an infinite left tangent33.

Technical details on computing multifractal spectrum in the wavelet domain can be found in S5 in SI. In addition, readers can find additional information on the definition of multifractal spectra using discrete wavelet transforms in33

Overall, analyzing the multifractal spectrum provides valuable insights into the complex behaviors of signals. It allows us to characterize the self-similarity and irregularity of signals and provides information about their inhomogeneity. Additionally, the multifractal spectrum enables the computation of descriptors related to the multi-scaled nature of signals that are not possible with monofractal behaviors. These descriptors can help explain differences between heart sound signals obtained from subjects with murmurs and those from healthy subjects.

Data analysis

According to the literature on heart murmur analysis, the specific location of a murmur does not significantly affect its detection. Therefore, we focused our analysis only on heart sound signals with murmurs present or absent at four different locations. Figure 3 provides an overview of the steps followed in the data analysis and details about each step are described below. Also, in the spirit of reproducible research, the software used for feature extraction is posted on Github page.

Step 1: feature extraction

-

Monofractal Features (slope): To ensure consistency in heart sound signal analysis, we standardized signal lengths by segmenting each recording into sub-signals of dyadic size 1024 (equivalent to 256 ms at a 4 kHz sampling rate). This approach is particularly suited for discrete wavelet transform (DWT), as it facilitates optimal multi-scale decomposition. Also, the length of 1024 is a compromise in which the scaling features are relatively constant within the segment, yet the number of dyadic scales needed for stable estimation of scaling features is sufficient. This segmentation strategy ensures a balance between computational efficiency and robustness, retaining key signal features without excessive fragmentation or redundancy. First, the DWT was performed in each sub-signal using the Daubechies 6 wavelet and then the wavelet spectrum was computed. The minimal phase Daubechies 6 wavelet was used because it balances the locality of representation and the smoothness of decomposing scaling function. Second, the spectral slope of each sub-signal was computed using wavelet energies at scale indexes from 6 to 9 because of the stability of linear relationship between wavelet energies and scale indexes in this range (see Fig. 4). The average slope over sub-signals was computed as the final feature per signal.

-

Wavelet Entropy: As with the slope computing procedure, the wavelet entropy for each sub-signal was computed using wavelet energies at the scales which were not involved in computing slope ( that is scales from 1 to 5). To calculate Shannon’s entropy, normalized wavelet energies were computed for each sub-signal, and then the coefficient of variation of the wavelet entropy was computed as the final feature for each signal.

-

Multifractal Features: Multifractal analysis was employed on the entire heart murmur signals using the same Daubechies 6 wavelet filter. The following properties were examined: spectral mode, left slope, right slope, left tangent, right tangent, left tangent point, right tangent point and broadness.

Finally, a total of ten multiscale descriptors were extracted to perform classification. They include slope, entropy, spectral mode, left slope, right slope, left tangent, right tangent, left tangent point, right tangent point and broadness.

Step 2: statistical analysis

In this study, the Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to determine whether the features extracted from the heart sound signals differed significantly between the normal and murmurous groups and whether these differences could be used to classify heart sound signals as either having murmur present or murmur absent. This test computes the sum of the ranks of the observations in one of the groups and compares it to the sum of the ranks of the observations in the other group. The test statistic is the smaller of these two sums, and its significance is determined by comparing it to the distribution of the test statistic under the null hypothesis that the two groups have the same distribution.

Step 3: classification models

First, we calculated an importance score for each feature in detecting murmur in order to further clarify the role that these features play in murmur detection. Using the Minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance (MRMR) algorithm, multiscale features were ranked based on their importance for classification. MRMR aims to select features that are highly relevant to the target class while minimizing redundancy between them. By balancing relevance (the correlation between a feature and the target variable) and redundancy (the overlap of information among features), MRMR identifies an optimal subset of features.

Second, the experiment involved the evaluation of four commonly used classification algorithms: logistic regression (LR), support vector machine (SVM), k-nearest neighbors (KNN), and neural network (NN). The classifier configurations are summarized in Table 1.

More information about these model specifications can be found on the on Github page.

Step 4: performance evaluation

Classification models were trained on 80% of the rows from each feature matrix, with the remaining rows used for testing. Additionally, the training dataset was further subdivided as 80% for training and the rest for validation. The imbalance in the number of murmurous and normal individuals could increase a bias in the performance evaluation. To minimize the impact of data imbalance and ensure a fair assessment, two performance evaluation methods were employed as follows:

-

Balanced Class Classification: An equal number of samples were selected from normal and murmurous groups prior to splitting the data for training, validation, and testing. That is, 616 subjects were randomly selected from the 2547 heart murmur absent cases to match the number of cases. The process of data selection, splitting, and model performance evaluation was repeated 100 times for each classifier, and the reported performance measures were averaged over these repetitions.

-

Weighted Class Classification: The classifiers, LR, SVM, and NN were trained with adjusted weights. Using a grid search hyperparameter optimization method, optimal class weights for each classifier were determined by taking the class weights that generated the maximum Area-Under-Curve (AUC) of the model for validation data.

Hyperparameter optimization

Grid search cross-validation technique was used to optimize hyperparameters of the classification models. This technique involves defining a grid of hyperparameter values and then training and evaluating a model for each combination of hyperparameters. Cross-validation is used to evaluate the performance of each model by splitting the data into training and validation sets multiple times and calculating the average validation score. In this study, 5-fold cross-validations were employed and the selection of optimal hyperparameters is based on the highest score in Area-Under-Curve (AUC) of Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve. Grid search cross-validation helps to ensure that the selected hyperparameters generalize well to unseen data and can improve the performance of a model. Table 1 summarizes classifier configurations.

The classifier performance was evaluated using sensitivity, specificity, AUC, and overall correct classification rate (accuracy).

Results

This section presents discriminatory behavior of the proposed features and then their potential in detecting murmurs of the heart sounds.

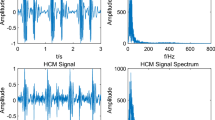

Self-similar nature in heart sound

To gain a basic understanding of the self-similar nature of heart sound signals, we selected a sample of normal and murmurous heart sound signals and analyzed their monofractal and multifractal spectra. The results are shown in Fig. 4, which displays the differences between the fractal properties of the two types of signals. The monofractal spectra show that the spectral slope for the signal with a murmur present is − 1.53, while it is − 1.72 for the signal without a murmur. These values were computed using wavelet energies from scale 9 to 14. That is, the murmurous heart sound indicates a higher degree of irregularity compared to the normal heart sound. Similarly, the multifractal spectra reveal eight different properties: spectral modes (0.51, 0.41), left slopes (0.83, 0.71), right slopes (− 0.70, − 0.59), broadness (0.52, 0.62), left tangents (1.4, 1.3), right tangents (1.00, − 0.80), left tangent points (− 0.75, − 0.69), and right tangent points (− 0.26, − 0.07). These values indicate different levels of differences in multiscale properties between the normal and murmurous heart sound signals.

Discriminatory level of the multiscale features

Figure 5 shows the distribution of individual features associated with murmurs present and absent. The results of the statistical analysis using the Wilcoxon rank sum test indicate that the medians of most features show a significant difference between the normal and murmurous groups (with a p-value \(< 0.05\)), except for the Right Tangent and Broadness in the multifractal spectra-based features. Overall, all the feature distributions exhibit varying levels of discriminatory behaviors between normal and murmurous heart sounds.

An overview of monofractal and multifractal properties of normal and murmurous heart sound. The first row shows a sample heart sound signal with and without a murmur. The slopes of the monofractal wavelet spectrum (second row) are − 1.53 and − 1.72, respectively, when murmurs are present and absent. Third row shows multifractal spectra and their properties are displayed as spectral modes (0.51, 0.41), left slopes (0.83, 0.71), right slopes (− 0.70, − 0.59), broadness (0.52, 0.62), left tangents (1.4, 1.3) and right tangents (1.00, − 0.80), left tangent points (− 0.75, − 0.69), and right tangent points (− 0.26, − 0.07).

It is important to note that the statistical significance of the differences in feature medians between cases and controls does not necessarily guarantee that these features will perform well in classifying heart murmur signals. The statistical analysis serves as a preliminary step to identify potentially informative features, which can then be used to train and test machine learning models. Thus, this analysis is exploratory, designed to identify candidate features for the task of classification.

Moreover, as illustrated in Fig. 6, the slope has the highest importance score, followed by spectral mode, right slope, and entropy. The remaining six features have importance scores below 0.005, with broadness being the least significant.

Murmur detection performance

Table 2 summarizes the classification performance obtained from the balanced class classification procedure. Based on grid search, the LR classifier was trained with saga solver, an L1 penalty term, and an inverse regularization strength of \(1 \times 10^{5}\). For the KNN classifier, we used 35 nearest neighbors and Minkowski distance metric. The SVM classifier was based on the linear kernel with a kernel scale of 0.01 and a box constraint of 10.0. The NN model used the ADAM optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001 and a learning rate decay of \(1 \times 10^{-6}\), and binary cross as the cost function. Overall, the NN classifier achieved the highest performance with a classification accuracy of \(65.70 \pm 3.99\), sensitivity of \(61.61 \pm\)11.15, specificity of \(70.17 \pm 15.33\), and an AUC of \(0.712 \pm 0.053\). This was followed by LR, SVM, and KNN classifiers.

The performance summarized in Table 3 is obtained from the weighted classifiers implemented using LR, SVM, and NN. The KNN model is not included as it is not able to train with adjusted class weights. By utilizing the grid search with the hyperparameters and the class weights, the optimal settings for each of these classifiers were determined. The LR classifier used the saga solver with L1 penalty term, an inverse regularization strength of 0.1, and the class weights of 1 for murmur absence and 4.5 for murmur presence. The SVM classifier used the RBF kernel with a kernel scale of 0.1, a box constraint of 100.0, and class weights of 1 for murmur absence and 4 for murmur presence. These best class weights were found using grid search with 5-fold cross-validation for LR and SVM models. For the NN model, the model parameters were as same as the NN model used in the repeated classifier method except for the class weights. Unlike SVM and LR, we explored ROC curve to find the optimal class weights for the NN model. After splitting training data into training and validation datasets, we trained a separate NN model on each of the eight different class weight values and computed the Youden index from sensitivity and 1-specificity obtained from each NN model. The class weights associated with the Youden index are the optimal class weights. As a result, the class weights used for the NN model were 0.62 for murmur absence and 2.54 for murmur presence. The SVM classifier achieved the highest performance with a classification accuracy of 76.61%, sensitivity of 82.12%, specificity of 54.02%, and an AUC of 0.741. This was followed by the NN and LR classifiers.

All in all, classification models with adjusted class weights perform better than the models without class weights.

Discussion

The main focus of this study is to propose a new set of multiscale features based on scaling and complexity properties of heart sounds in the wavelet domain and evaluate their effectiveness in detecting heart murmurs. A comparison of the proposed approach with previously proposed methods is also presented, demonstrating the possibility that it has the potential to enhance murmur detection.

This study employs wavelet analysis to extract scaling nature-based features from heart sound signals in the time-frequency domain, offering a fresh perspective compared to traditional time-domain analysis methods. The proposed methodology demonstrates that the multiscale features extracted contribute to enhanced detection of heart murmurs compared to existing methods that primarily involve the segmentation of S1 and S2 sounds. This is because the use of multiscale features allows for capturing unique and hidden dynamics in heart sound signals that cannot be revealed through conventional feature engineering methods typically used in statistical analyses. Additionally, discrete wavelet transforms effectively filter heart murmurs while preserving S1 and S2 sound patterns16. As a result, the feature distributions shown in Fig. 5 indicate that normal and murmurous heart sounds differ in terms of their discriminatory levels of multiscale properties.

The varying discriminatory levels of the extracted features provide important physiological insights into the characteristics of murmurous and normal heart sounds. Wavelet entropy, which measures signal complexity, is lower in murmurous sounds due to their structured turbulence caused by abnormal blood flow. Slope, an indicator of long-range dependence and smoothness, is more negative in cases, reflecting the greater persistence of murmurous signals. Multifractal descriptors, such as spectral mode, broadness, and left slope, capture signal irregularities associated with pathological murmurs. A higher spectral mode in murmurous sounds suggests smoother, more repetitive signal segments, while broadness indicates deviation from monofractality, implying that normal heart sounds exhibit more complex dynamics. Similarly, a higher right slope in murmurous sounds suggests increased multifractality, highlighting structural variations caused by abnormal hemodynamic forces. Our observations are consistent with previous studies on multifractality in cardiovascular disease analysis35,36,37. These findings emphasize the clinical utility of these features in distinguishing normal and pathological heart sounds, providing valuable insights for automated murmur detection and risk assessment.

As a result of the multiscale analysis of heart signals, we are enabled to obtain information about heart sounds that are not readily observable in the time domain, resulting in a number of advantages. A key advantage of this approach is that it uses fewer features than existing DL methods for the same dataset while still achieving performance similar to that of existing methods. Table 4 compares the feature extraction domain, feature extraction method, number of features, and performance of our proposed method with previous studies that used the same CirCor dataset. It can be seen that existing studies have used characteristics of heart sounds in the time, frequency, and time-frequency domains to build machine learning models. When comparing the model complexity in terms of the number of features, the classifiers proposed in this study are relatively much simpler while still achieving comparable (or even better) performance. Another advantage of the methodology is that it requires only minimal pre-processing, unlike existing techniques that heavily rely on pre-processing heart sounds, thus limiting their generalizability and reproducibility.

This study underscores the importance of analyzing self-similar properties in heart sound signals within the frequency domain to extract features that reveal hidden dynamics. However, it is important to note that the proposed approach can still be improved in performance. This is because, as shown in Table 4, the deep learning (DL) models proposed in8,10,19,42 outperform the approach presented here. Several reasons might be at play, and three of the most likely ones are briefly outlined along with strategies for improving performance beyond DL models. First, the multiscale descriptors alone cannot achieve state-of-the-art performance as they cannot extract all discriminatory information from heart sounds and hence additional features are necessary. As described in43, diagnostic performance can be improved by integrating features extracted from independent domains. Thus, the proposed wavelet-domain features with descriptors from other domains, such as time-domain features. Second, while a linear decay in wavelet energies is typically expected across increasing scales when assessing monofractal properties, the wavelet spectra in Fig. 4 show a linear decay only at higher scales. This may be influenced by noise or outliers in signals. Consequently, the wavelet energies at these scales were used to compute the slope, ignoring wavelet energies at lower scales. Utilizing advanced measures, such as distance variance43 and pairwise wavelet energies22, can enhance performance by minimizing such issues and enabling more precise computation of multiscale descriptors. Third, this study assumes a stationary scaling nature when computing the proposed features. However, accounting for the time-variant nature of scaling could lead to more accurate characterization and improved murmur detection. While this study does not explore such refinements, as the primary goal is to highlight the potential of multiscale features in murmur detection, these approaches can be considered for future work.

In addition, the proposed methodology also presents certain challenges that may need to be addressed in future studies. For example, as shown in Fig. 4, the scale index range used to calculate slope values was restricted from 9 to 14, which may not be suitable for all signals and could result in slope values outside the theoretically expected range of -3 to -1 (as illustrated in Fig. 5). Similarly, selecting an appropriate range of moment q that is suitable for all signals when calculating multifractal spectra also presented challenges. The range \(q = [3, 12]\) was applicable to over 90% of signals, but for some signals, it resulted in numerical instability. As a result, a shorter range of 3 to 10 was used for which the range \(q = [3, 12]\) did not work. Consequently, the generalizability of the proposed procedure is limited so further investigation is needed to identify more generalizable values for these parameters. Additionally, the study used the discrete wavelet transform (DWT), which requires the signal length to be a power of two. Therefore, the maximum possible signal length that satisfies this condition was selected, resulting in some information loss. This can be overcome by replacing DWT with non-decimated wavelet transform as it allows performing wavelet transform on a signal of any length. Furthermore, the original dataset includes additional features such as age, gender, height and weight and it would be interesting to investigate how the proposed multiscale features are related to these features and their impact on the presence of murmurs.

When developing classification models, one of the main challenges of this study is the imbalanced data, with 2547 normal heart sound signals compared to only 616 signals with a murmur. This imbalance can lead to classifiers becoming biased towards the majority class, in this case, the normal heart sound signals. Although classification with adjusted class weights is an option and performs well as shown in this study, adjusting the cost function by heavily weighting the minority class can result in a significant trade-off between sensitivity and specificity. Overall, the weighting method can lead to an increase in false positives, which limits the practical usefulness of the proposed neural network model. Therefore, to improve the practical usefulness of the model, it would be more beneficial to focus on specific cardiac diseases rather than a general abnormality in heart sounds.

Conclusions

This study introduces a new set of multiscale features based on scaling properties and entropy of heart sound signals. Scaling properties in heart sound signals are assessed by considering monofractal and multifractal behaviors in the wavelet domain. The potential of accurately detecting murmur of these features is assessed by developing a neural network-based classifier and standard classifiers. The application of proposed features on heart sound signals showed the ability to detect murmurous heat sound with an accuracy of over 76.61%. Compared to existing methods, the proposed approach is simpler but achieves comparable results. Therefore, the multiscale features could serve as potential biomarkers for automated heart murmur detection. Although the performance of this approach is less competitive compared to some state-of-the-art deep learning models, the improved interpretability, lower model complexity, and less reduced computational cost are key advantages.

The study underscores the significance of using the scaling properties of heart sounds, offering new insights and opportunities for advancing heart murmur detection methods. In particular, the scaling modalities in data mining are independent of currently used modalities and combining them has a potential for future improvement. For instance, given that some existing approaches rely solely on time-domain features, it would be valuable to evaluate murmur detection performance by integrating both time-domain and wavelet-domain features. The combination of features from independent domains typically enhances learning performance43.

However, the scaling descriptors proposed in this study assume that scaling properties remain constant over time. More precise computations could be achieved by accounting for the time-variant behavior of these properties, potentially leading to improved performance. Additionally, exploring advanced measures to better characterize scaling properties, such as those proposed by22, represents a promising direction for developing more effective murmur detection techniques.

Data availability

The dataset during the current study is available at https://physionet.org/content/challenge-2022/1.0.0/.

References

WHO. WHO reveals leading causes of death and disability worldwide: 2000–2019 (2020).

Tsao, C. W. et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2022 update: a report from the american heart association. Circulation 145, e153–e639 (2022).

Peters, D. H. et al. Poverty and access to health care in developing countries. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1136, 161–171 (2008).

Chorba, J. S. et al. Deep learning algorithm for automated cardiac murmur detection via a digital stethoscope platform. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 10, 019905 (2021).

Noman, F., Ting, C.-M., Salleh, S.-H. & Ombao, H. Short-segment heart sound classification using an ensemble of deep convolutional neural networks. In ICASSP 2019-2019 IEEE international conference on acoustics, speech and signal processing (ICASSP), 1318–1322 (IEEE, 2019).

Lee, J. et al. Deep learning based heart murmur detection using frequency-time domain features of heartbeat sounds. In 2022 Computing in Cardiology (CinC) 498, 1–4 (2022).

Almanifi, O. R. A., Ab Nasir, A. F., Mohd Razman, M. A., Musa, R. M. & P.P. Abdul Majeed, A. Heartbeat murmurs detection in phonocardiogram recordings via transfer learning. Alex. Eng. J. 61, 10995–11002 (2022).

McDonald, A., Gales, M. J. & Agarwal, A. Detection of heart murmurs in phonocardiograms with parallel hidden semi-markov models. In 2022 Computing in Cardiology (CinC) 498, 1–4 (2022).

Walker, B. et al. Dual bayesian resnet: A deep learning approach to heart murmur detection. Comput. Cardiol. (2022).

Lu, H. et al. A lightweight robust approach for automatic heart murmurs and clinical outcomes classification from phonocardiogram recordings. In 2022 Computing in Cardiology (CinC) 498, 1–4 (2022).

Lim, G. B. Ai used to detect cardiac murmurs. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 18, 460–460 (2021).

Nivitha Varghees, V. & Ramachandran, K. I. Effective heart sound segmentation and murmur classification using empirical wavelet transform and instantaneous phase for electronic stethoscope. IEEE Sens. J. 17, 3861–3872 (2017).

Min, S., Lee, B. & Yoon, S. Deep learning in bioinformatics. Brief. Bioinform. 18, 851–869 (2016).

Zheng, Y., Guo, X., Wang, Y., Qin, J. & Lv, F. A multi-scale and multi-domain heart sound feature-based machine learning model for acc/aha heart failure stage classification. Physiol. Meas. 43, 065002 (2022).

Jayalakshmy, S., Lakshmipriya, B., Vinothini, C. & Revathi, R. Wavelet packet descriptors for physiological signal classification. In 2021 IEEE Madras Section Conference (MASCON), 1–6 (2021).

Cherif, L. H., Debbal, S. & Bereksi-Reguig, F. Choice of the wavelet analyzing in the phonocardiogram signal analysis using the discrete and the packet wavelet transform. Expert Syst. Appl. 37, 913–918 (2010).

Ismail, S., Siddiqi, I. & Akram, U. Localization and classification of heart beats in phonocardiography signals-a comprehensive review. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process. 1–27 (2018).

Summerton, S. et al. Two-stage classification for detecting murmurs from phonocardiograms using deep and expert features. In Computing in Cardiology 2022: 49th Computing in Cardiology Conference (2022).

Patwa, A., Rahman, M. M. U. & Al-Naffouri, T. Y. Heart murmur and abnormal pcg detection via wavelet scattering transform & a 1d-cnn (2023). arxiv: 2303.11423.

Yaseen, S. G.-Y. & Kwon, S. Classification of heart sound signal using multiple features. Appl. Sci. 8 (2018).

Vimalajeewa, D., McDonald, E., Tung, M. & Vidakovic, B. Parkinson’s disease diagnosis with gait characteristics extracted using wavelet transforms (2022).

Vimalajeewa, D., Hinton, R. J., Ruggeri, F. & Vidakovic, B. An advanced self-similarity measure: Average of level-pairwise hurst exponent estimates (ALPHEE). TecharXiv (2024).

Oliveira, J. et al. The circor digiscope dataset: From murmur detection to murmur classification. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 26, 2524–2535 (2022).

Reyna, M. A. et al. Heart murmur detection from phonocardiogram recordings: The george b. moody physionet challenge 2022. medRxiv (2022).

DeGroff, C. G. et al. Artificial neural network-based method of screening heart murmurs in children. Circulation 103, 2711–2716 (2001).

Bhatikar, S. R., DeGroff, C. G. & Mahajan, R. L. A classifier based on the artificial neural network approach for cardiologic auscultation in pediatrics. Artif. Intell. Med. 33, 251–260 (2005).

Chorba, J. S. et al. Deep learning algorithm for automated cardiac murmur detection via a digital stethoscope platform. J. Am. Heart Assoc. (2021).

Wei, W., Zhan, G., Wang, X., Zhang, P. & Yan, Y. A novel method for automatic heart murmur diagnosis using phonocardiogram (2019).

Chen, Y., Wang, S., Shen, C.-H. & Choy, F. K. Intelligent identification of childhood musical murmurs. J. Healthcare Eng. 3, 125–139 (2012).

Chen, W. et al. 1. deep learning methods for heart sounds classification: A systematic review. Entropy (2021).

Mallat, S. A theory for multiresolution signal decomposition: the wavelet representation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 11, 674–693 (1989).

Vidakovic, B. Statistical modeling by wavelets (John Wiley & Sons, 2009).

Goncalves, P., Riedi, R. & Baraniuk, R. A simple statistical analysis of wavelet-based multifractal spectrum estimation. In Conference Record of Thirty-Second Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems and Computers (Cat. No.98CH36284), vol. 1, 287–291 vol.1 (1998).

Rosso, O. A. et al. Wavelet entropy: a new tool for analysis of short duration brain electrical signals. J. Neurosci. Methods 105, 65–75 (2001).

Ivanov, P. C. et al. Multifractality in human heartbeat dynamics. Nature 399, 461–465 (1999).

Rufiner, H. L., Castiglioni, P., Lazzeroni, D., Coruzzi, P. & Faini, A. Multifractal-multiscale analysis of cardiovascular signals: A dfa-based characterization of blood pressure and heart-rate complexity by gender. Complexity 2018, 4801924 (2018).

Li, J. et al. The effect of circadian rhythm on the correlation and multifractality of heart rate signals during exercise. Phys. A 509, 1207–1213 (2018).

Jalali, K., Saket, M. A. & Noorzadeh, S. Heart murmur detection and clinical outcome prediction using multilayer perceptron classifier. In 2022 Computing in Cardiology (CinC) 498, 1–4 (2022).

Monteiro, S., Fred, A. & da Silva, H. P. Detection of heart sound murmurs and clinical outcome with bidirectional long short-term memory networks. In 2022 Computing in Cardiology (CinC) 498, 1–4 (2022).

Ballas, A., Papapanagiotou, V., Delopoulos, A. & Diou, C. Listen2yourheart: A self-supervised approach for detecting murmur in heart-beat sounds (2022). arxiv: 2208.14845.

Fuadah, Y. N., Pramudito, M. A. & Lim, K. M. An optimal approach for heart sound classification using grid search in hyperparameter optimization of machine learning. Bioengineering 10 (2023).

Panah, D. S., Hines, A. & McKeever, S. Exploring wav2vec 2.0 model for heart murmur detection. In 2023 31st European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO), 1010–1014 (2023).

Vimalajeewa, D., Bruce, S. A. & Vidakovic, B. Early detection of ovarian cancer by wavelet analysis of protein mass spectra. Stat. Med. (2023).

Acknowledgements

The research of C.L and B.V. was supported by Herman Otto Hartley endowed chair funds at Texas A&M University. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Portions of this research were conducted with the advanced computing resources provided by Texas A&M High-Performance Research Computing. The authors also thank the editor and two anonymous referees for insightful comments that improved the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.V., C. L., and B. V. contributed equally to this work. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All authors have given their consent for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vimalajeewa, D., Lee, C. & Vidakovic, B. Multiscale analysis of heart sound signals in the wavelet domain for heart murmur detection. Sci Rep 15, 10315 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93989-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93989-0