Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of e-cigarette usage and its correlation with mental health disorders among undergraduate medical and health sciences students. A descriptive cross-sectional correlational study was conducted among 320 undergraduate students from four colleges (MBBS, BDS, B Pharm, BSN) at RAK Medical and Health Sciences University in the UAE. Stratified random sampling was used, and data was collected through face-to-face interviews using validated mental health assessment tools. Approximately one-third (35%) reported using vape, with a statistically significant relationship found between vaping and the socio-demographic characteristics of the students, such as sex and college type (P ≤ 0.05). Moreover, there was a significant correlation between vaping and depression, anxiety, Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome, and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. However, there were no significant correlations found between vaping and self-esteem or eating disorders. Vaping is prevalent among undergraduate medical and health sciences students and is linked to compromised mental health. These findings underscore the need for targeted mental health campaigns and e-cigarette screening programs. Further longitudinal studies are necessary to explore causal relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The use of e-cigarettes has emerged as a global public health concern, particularly among young adults. Traditional tobacco smoking has long been associated with adverse health outcomes, and while its prevalence has declined, e-cigarette usage has surged. E-cigarettes, battery-operated devices that deliver nicotine via inhalable aerosols, are marketed as a safer alternative to traditional cigarettes. However, concerns have been raised regarding their long-term health effects, potential role in nicotine addiction, and implications for mental health1,2,3. These concerns extend to the potential impact on the healthcare system, as the long-term health effects of e-cigarettes could lead to increased healthcare costs and a higher burden on healthcare providers.

The popularity of e-cigarettes is significantly influenced by aggressive marketing, appealing flavors, and most notably, social media exposure. Research indicates that social media platforms play a crucial role in normalizing vaping. They feature influencers promoting e-cigarettes, targeted advertising, and user-generated content that all frame vaping as socially desirable and risk-free. Platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube have a profound influence on how young people perceive vaping. The constant exposure to influencers, ads, and user-generated content makes vaping seem cool, trendy, and customary. For many teens and young adults, this constant exposure makes vaping seem like just another part of life, something everyone is doing. Research suggests that social media platforms play a pivotal role in normalizing and promoting vaping behaviors, particularly among young adults4,5.

In university settings, students often experiment with substances as part of socialization, stress relief, or curiosity. The prevalence of e-cigarette use among college students varies widely, ranging from 17.7 to 40%, with nearly 60% having been exposed to vaping at least once6,7,8. Studies across regions report varied prevalence rates influenced by cultural norms, tobacco control policies, and marketing exposure9,10,11. For instance, research indicates that vaping rates are higher in countries with lenient regulations and aggressive e-cigarette marketing campaigns12,13,14. However, the distinction between experimental use and regular vaping remains unclear in much of the literature. It’s important to note that e-cigarette use can also have a significant impact on academic performance, as it may lead to increased absenteeism, decreased concentration, and poor decision-making, further highlighting the need for effective tobacco control policies in educational institutions.

Mental health concerns, such as anxiety and depression, have been linked to substance use, including traditional tobacco smoking. Recent evidence suggests a comparable relationship between e-cigarette use and mental health disorders, including depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)9,10,11. While traditional cigarettes have long been linked to mental health issues, e-cigarettes bring new challenges due to their changing formulas and the way they are used. Studies show that nicotine and other chemicals in e-cigarettes may affect brain function, leading to mood swings, anxiety, and depressive symptoms. Several studies highlight nicotine’s impact on neurotransmitter systems, which may contribute to increased psychiatric symptoms among users12,13,14. However, the need for further research on the mental health implications of e-cigarette use is urgent. The self-medication hypothesis suggests that individuals with pre-existing mental health conditions may use e-cigarettes to alleviate symptoms, thereby reinforcing nicotine dependence15. Possible mechanisms include nicotine-induced neurobiological changes, self-medication for underlying mental health conditions, and the exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms due to nicotine dependence12. Studies suggest that nicotine affects neurotransmitter systems, altering dopamine release and contributing to mood disorders13,14,15. Additionally, vaping may serve as a coping mechanism for individuals with pre-existing psychiatric conditions, further reinforcing nicotine addiction16,17,18.

This study aims to fill a gap in existing research by specifically examining vaping behaviors among undergraduate medical and health sciences students. Unlike previous studies that focus on the general youth population, this research provides insights into a unique demographic because, despite their access to health education and awareness of the risks associated with e-cigarette use, they still engage in vaping. By understanding the relationship between vaping and mental health in this context, we can inform targeted intervention strategies.

Methods

Design and settings

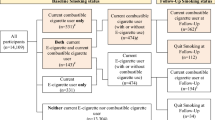

A descriptive cross-sectional correlational study at RAK Medical and Health Science University in UAE, which serves as a culturally diverse student body involving undergraduate health sciences students from four colleges (MBBS, BDS, B Pharm, and BSN). The sample size was calculated based on the total number of students from the four colleges (N = 1151), using the Rao soft program (Sample Size Calculator by Roa soft, Inc, 2014)19, with an accepted margin of error of 5% and a confidence level of 95% the response distribution is 50%, confidence level at 95%. The sample size is n = 320.

The study used stratified random sampling technique using this formula: (sample size/population size) x stratum size) as follows; 131 students from MBBS, 74 students from BDS, 34 students from B Pharm and 81 students from BSN.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Undergraduate students from all four colleges (MBBS, BDS, B Pharm, BSN) aged 18 or older who provided informed consent were included. The study excluded students undergoing active treatment for mental health disorders, ensuring that the sample included students from all medical and health sciences disciplines while acknowledging potential selection bias.

Data collection

Participants were recruited via email invitations and classroom announcements. Informed consent was obtained before face-to-face interviews, ensuring confidentiality. Data was collected via face-to-face interviews, which lasted about 20 min for everyone sharing the survey. Moreover, the responses were recorded anonymously to maintain participant privacy. Ethical approval was granted by the RAK Medical and Health Sciences University Research Ethics Committee, ensuring adherence to ethical guidelines for human research. The data collection tools are validated instruments selected for their reliability and appropriateness for university students and their wide usage among young adults to assess mental health conditions accurately. Moreover, it consisted of seven semi-structured tools as follows:

Tool I

Socio-Demographic Characteristics: This includes questions on gender, age, nationality, GPA, year in the University, and history of vaping.

Tool II

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) is a self-administered tool used to diagnose common mental disorders based on the PRIME-MD diagnostic instrument. It is a depression assessment tool that assigns scores ranging from “0” (indicating no presence) to “3” (indicating near-daily presence) for each of the nine criteria outlined in the DSM-IV. This tool is widely acknowledged for its exceptional reliability, as seen by Cronbach’s alpha values, which typically fall between 0.86 and 0.89, demonstrating robust internal consistency. Moreover, it was tested for validity, making it a reliable tool for assessing depression in diverse populations20.

Tool III

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7) questionnaire consists of 7 questions. A score of 10 or more indicates the presence of clinically severe anxiety. The measure commences with assessing an individual’s lifetime exposure to stressful experiences. The assessment evaluates the prevalence of the four prevalent anxiety disorders, namely Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Panic Disorder, Social Phobia, and posttraumatic stress disorder (Spitzer et al., 1999)21. The GAD-7 has shown strong internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values of approximately 0.92, suggesting it consistently evaluates anxiety symptoms. The validity of this scale has been well established, demonstrating high agreement with other measures of anxiety21.

Tool V

The Primary Care Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Screen (PC-PTSD), developed by Prins et al. (2003)22, is a four-item measure that reflects the primary Care PTSD Screen (PC-PTSD) (four questions with a score of ≥ 3 indicating probable posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Grant et al. (2019) used this tool among the students7.

Tool VI

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, developed by Rosenberg in 1965, is a self-reported measure that evaluates overall self-esteem. The assessment consists of ten items scored on a 4-point Likert scale to measure present self-esteem. There is a positive correlation between the score achieved in the RSE and the levels of self-esteem. In other words, as the score in the RSE increases, the levels of self-esteem also increase. Cronbach’s alpha value measured the reliability of this tool between 0.77 and 0.88, which indicates an accurate measurement of self-esteem. The RSES has undergone thorough validation across several cultural and demographic groups, demonstrating robust construct validity (Rosenberg et al., 1965)23.

Tool VII

The Adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Self-Report Scale (ASRS-v1.1) Part A is a 6-question screening tool for ADHD developed by Kessler et al. in 2005. It is used to determine whether an individual is experiencing the symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). α Values were between 0.88 and 0.89, demonstrating reliability in assessing ADHD symptoms (Kessler et al., 2005)24.

Tool VIII

This tool was adapted from the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q), a widely used instrument for assessing disordered eating behaviors. It included questions on weight control behaviors such as restrictive dieting, binge eating, and compensatory behaviors like vomiting or excessive exercise25. The assessment of the tool’s validity and reliability yielded a coefficient of α = 0.75.

All the instruments were examined for cultural adaptation relevant to a diverse population (Arabic and English-speaking), given the cultural diversity in the UAE. Feasibility was tested on 10% of the sample in a pilot study. A pilot analysis determined their feasibility and applicability, and experts in each language validated all translations to ensure consistency with all other versions of the tools.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used for demographic characteristics. The chi-square test analyzed categorical data, while t-tests and ANOVA compared mean differences. Logistic regression was conducted to assess predictors of vaping, with odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) reported.

Results

Demographic and vaping prevalence

The study included 320 participants (74.2% male, 25.8% female), with 35% reporting e-cigarette use. Significant differences were observed between vaping behavior and gender, as well as college type (P ≤ 0.05) (Tables 1 and 2).

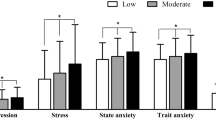

Vaping and mental health

Significant correlations were found between vaping and depression (r = -0.149, P = 0.008, weak correlation), PTSD (r = -0.203, P = 0.000, moderate correlation), and ADHD (r = -0.076, P = 0.005, weak correlation). These correlations suggest that while vaping is associated with these mental health conditions, the strength of these relationships varies.

The moderate correlation with PTSD indicates a more substantial link compared to the weaker associations found with depression and ADHD, highlighting the need for further research into causality and underlying mechanisms. No significant associations were found with self-esteem (P = 0.824) or eating disorders (P = 0.368) (Tables 2 and 3).

Logistic regression analysis

Vaping was significantly associated with male gender (OR = 3.35, 95% CI: 1.59–7.04, P = 0.001), indicating that males were over three times more likely to vape than females. PTSD (OR = 1.012, 95% CI: 1.001–1.023, P = 0.039) and ADHD (OR = 1.008, 95% CI: 1.000-1.016, P = 0.038) showed significant associations, suggesting that individuals with these conditions had slightly higher odds of vaping. These findings emphasize the need for targeted mental health interventions to address potential vaping-related coping behaviors. (Table 4).

Discussion

This study confirms that vaping is prevalent among medical and health sciences students and is associated with adverse mental health outcomes. The relationship between vaping and depression, anxiety, PTSD, and ADHD aligns with prior research suggesting that nicotine dependence may exacerbate psychiatric symptoms. The relationship between vaping and depression, anxiety, PTSD, and ADHD aligns with prior research suggesting that nicotine dependence may exacerbate psychiatric symptoms12,13,14. However, due to the cross-sectional nature of this study, it is not possible to determine whether vaping contributes to mental health conditions or if individuals with these conditions are more likely to vape26. Future longitudinal studies are needed to explore causality.

The prevalence of vaping in this study (35%) is higher than that reported in studies from Pakistan (6%)27 but similar to the findings from Saudi Arabia (31%)28. These differences may reflect variations in cultural norms, tobacco control policies, and product availability across regions. Further research is needed to explore these contextual factors. Social media trends have played a significant role in promoting the use of E-Cigarettes, with influences targeting youngsters and promoting the idea that it is both safe and socially acceptable. This has led to a higher risk of use among adolescents with impulsive personality traits, who are not only using vape at a younger age but also using them more frequently, exacerbating the issue29.

In addition, a significant association between vaping usage and demographic factors like gender and college type was found. This aligns with prior research indicating higher e-cigarette use among males compared to females30. The variation across college types could relate to differing norms, peer influences, or other unmeasured factors specific to each academic program.

Nicotine, a psychoactive substance, influences receptors distributed widely in the brain. Preclinical data have uncovered potential long-term effects of adolescent nicotine consumption on brain structure and function31. Regular nicotine use can lead to increased anxiety and depression. Many individuals turn to be vaping to cope with stress or focus issues, but over time, this reliance can worsen mental health symptoms. Understanding whether chronic nicotine consumption, from conventional smoking or vaping, has any untoward or beneficial effects on brain development and mental health in humans is a significant area of research.

Analyses revealed significant relationships between vaping and increased symptoms of depression (higher PHQ-9 scores), anxiety (higher GAD-7 scores), PTSD (higher PC-PTSD-5 scores), and ADHD (higher ADHD scores). Published data provides strong proof that the prevalence of depression is higher among adolescent users of E-Cigarettes compared to non-users32,33. This correlation implies that using electronic cigarettes exclusively is linked to adverse psychological effects while using them by individuals who currently or have previously smoked conventional cigarettes can worsen existing symptoms of mental diseases to a greater extent.

Vaping showed negative correlations with measures of depression, anxiety, PTSD, and ADHD, suggesting that increased vaping was linked to poorer mental health in these dimensions. The strength of these correlations varied from mild to moderate. Overall, the findings indicate that vaping is prevalent among this university population and is associated with markers of compromised mental health, notably internalizing problems like depression and anxiety.

Vape smokers were more likely to experience higher total ADHD scores compared to non-smokers. This corroborates existing evidence that ADHD predicts the commencement of tobacco and nicotine product consumption in adolescents and young adults34. Students with ADHD may use vaping as a form of self-medication or be more susceptible to developing nicotine dependence. Regarding PTSD, the correlational analysis revealed a negative relationship, suggesting increased vaping may exacerbate PTSD. This aligns with research indicating that both combustible and e-cigarette use is linked to PTSD35. However, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences.

Furthermore, our study found no significant association between vaping and eating disorders among certain college types. This contrasts with the findings of Ganson et al. (2021), which indicate that college students who vape or use e-cigarettes are at a higher risk of developing an eating disorder. Notably, our results indicated no significant associations between vaping and self-esteem (RSES) or disordered eating behaviors35. While some studies have linked smoking and vaping to lower self-esteem35. This may be due to cultural differences, variations in measurement tools, or self-reporting biases. Possible explanations include cultural differences, measurement variations, or underreporting due to social desirability bias.

This study adopted correlational analysis models between vaping and various mental health parameters. There was a correlation significance between vaping and mental health indicators like depression, anxiety, and PTSD. This reinforces prior longitudinal evidence that these internalizing problems may increase susceptibility to initiating and continuing vaping36. Conversely, vaping could exacerbate these conditions, highlighting the need to limit youth access and appeal of e-cigarette products. The correlation coefficients were relatively modest, suggesting small-to-medium effect sizes. This aligns with evidence indicating small-to-moderate relationships between smoking and internalizing disorders like depression and anxiety37. Stronger associations may emerge in clinical samples with more severe psychopathology.

The results of univariate and multivariate regression analysis found a significant relation between usage of vape and age, college type, PHQ-9, GAD-7, P.C.–PTSD5, Rosenberg Self-Esteem, Adult ADHD Self-Report, and vomiting. The findings of this study underscore the pivotal role of healthcare experts in intervening and evaluating the use of e-cigarettes to offer smoking cessation programs for students. Utilizing social media for outreach campaigns can be a powerful method to disseminate awareness. Primary care providers should take the lead in conducting screenings to assess the prevalence of vaping among young individuals. It is essential for healthcare experts to advocate for the cessation of vaping among young individuals to prevent the potential development of nicotine dependence as a coping mechanism.

Relevance to clinical practice

This study’s findings reveal that awareness campaigns within universities can educate students on the potential risks associated with vaping and mental health. Universities should implement mental health screenings that include e-cigarette use assessments. Counseling programs targeting vaping cessation may be beneficial, and stricter public health policies should regulate the marketing of flavored vaping products, particularly on social media, to prevent youth initiation. Additionally, policymakers should consider implementing campus-wide restrictions on e-cigarette sales and usage, along with awareness campaigns to educate students on the mental health risks associated with vaping. Healthcare professionals should be trained to discuss vaping-related risks during routine health check-ups, ensuring students receive accurate information and support if they wish to quit.

Limitation and future research

The findings relied on self-report questionnaires, which can be susceptible to recall biases and socially desirable responses. Additionally, confounding factors such as socioeconomic status were not fully controlled. To get a clearer and more accurate picture, future longitudinal studies incorporating biochemical testing (e.g., checking for nicotine in the body) are recommended.

Conclusion

The results of this study revealed that vaping was prevalent among undergraduate medical and health sciences students in the UAE and was associated with increased symptoms of depression, anxiety, Post Traumatic Stress Dis, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. These findings underscore the need for targeted interventions, including mental health campaigns and e-cigarette screening programs, to address this emerging public health concern. Further research, particularly longitudinal studies, is needed to explore the causal pathways between vaping and mental health.

Ethical considerations

The researchers conducted this study per the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. After obtaining ethical approval from the Research and Ethics Committee (RAKMHSU-REC-055-2022/23-UG-N). The researchers comprehensively explained the study’s objectives and specifics using an online survey. Participants were then requested to give their voluntary assent by signing the informed consent form. The research was conducted anonymously and saved on a computer that required a password for access, ensuring the utmost security of the data and the confidentiality of the participants.

Data availability

Data will be shared by the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- E-cigarette:

-

Electronic cigarette

- PHQ-9:

-

The patient health questionnaire

- DSM-IV:

-

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders

- GAD-7:

-

The generalized anxiety disorder 7

- ADHD:

-

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- RSES:

-

Rosenberg self-esteem scale

- PC-PTSD:

-

The primary care post traumatic stress disorder screen

References

U.S. Department of health and human services. E-cigarette Use among Youth and Young Adults. A Report of the Surgeon General (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for disease control and prevention, national center for chronic disease prevention and health promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2016).

Pisinger, C. & Døssing, M. A systematic review of health effects of electronic cigarettes. Prev. Med. 69, 248–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.10.009 (2014).

Willett, J. G. et al. Recognition, use, and perceptions of JUUL among youth and young adults. Tob. Control. 28 (1), 115–116 (2019).

Mantey, D. S., Cooper, M. R., Clendennen, S. L., Pasch, K. E. & Perry, C. L. E-cigarette marketing exposure is associated with e-cigarette use among U.S. Youth. J. Adolesc. Health. 58 (6), 686–690 (2016).

Lanza, H. I. & Teeter, H. Electronic nicotine delivery systems (E-cigarette/Vape) use and co-occurring health-risk behaviors among an ethnically diverse sample of young adults. Substit. Misuse. 53 (1), 154–161 (2018).

Delnevo, C. D. et al. Patterns of electronic cigarette use among adults in the united States. Nicotine Tob. Res. 18, 715–719 (2016).

Grant, J. E., Lust, K., Fridberg, D. J., King, A. C. & Chamberlain, S. R. E-cigarette use (vaping) is associated with illicit drug use, mental health problems, and impulsivity in university students. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry. 31 (1), 27 (2019).

Copeland, A. L., Peltier, M. R. & Waldo, K. Perceived risk and benefits of e-cigarette use among college students. Addict. Behav. 71, 31–37 (2017).

Wallace, L. N. & Roache, M. J. Vaping in context: links among E-cigarette use, social status, and peer influence for college students. J. Drug Educ. 48 (102), 36–53 (2018).

Schoenborn, C. & Gindi, R. Cigarette smoking status among current adult E-cigarette users, by age group—National health interview survey, united States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 65 (42), 1177 (2016).

Coleman, B. N. et al. Association between electronic cigarette use and openness to cigarette smoking among U.S. Young adults. Nicotine Tob. Res. 17 (2), 212–218 (2015).

Smith, R. F. et al. Adolescent nicotine induces persisting changes in the development of neural connectivity. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 55 432 – 43, Association between initial use of e-cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(8):788 – 97. (2015).

Achenbach, T. M., Ivanova, M. Y., Rescorla, L. A., Turner, L. V. & Althoff, R. R. Internalizing/externalizing problems: review and recommendations for clinical and research applications. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 55 (8), 647–665 (2016).

Goldenson, N. I., Khoddam, R., Stone, M. D. & Leventhal, A. M. Associations of ADHD symptoms with smoking and alternative tobacco product use initiation during adolescence. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 43 (6), 613–624 (2018).

Green, V. R. et al. Mental health problems and onset of tobacco use among 12- to 24-year-olds in the PATH study. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 57 (12), 944–954 (2018).

Bandiera, F. C., Loukas, A., Li, X., Wilkinson, A. V. & Perry, C. L. Depressive symptoms predict current e-cigarette use among college students in Texas. Nicotine Tob. Res. 19 (9), 1102–1106 (2017).

Lechner, W. V., Janssen, T., Kahler, C. W., Audrain-McGovern, J. & Leventhal, A. M. Bi-directional associations of electronic and combustible cigarette use onset patterns with depressive symptoms in adolescents. Prev. Med. 96, 73–78 (2017).

Pham, T. et al. Electronic cigarette use and mental health: A Canadian population-based study. J. Affect. Disord 260, 646–652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.09.026 (2020).

Raosoft, I. Sample size calculator. Available from: http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html [Accessed October 2024].

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 16 (9), 606–613 (2001).

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. & Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 166 (10), 1092–1097 (2006).

Prins, A. et al. The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Prim. Care Psychiatry. 9 (1), 9–14 (2003).

Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent self-image (Princeton University Press, 1965).

Kessler, R. C. et al. The world health organization adult ADHD Self-Report scale (ASRS) is a short screening scale for the general population. Psychol. Med. 35 (2), 245–256 (2005).

Fairburn, C. G. & Beglin, S. J. Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? Int. J. Eat. Disord. 16 (4), 363–370. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(199412)16:4 (1994).

Becker, T. D. & Rice, T. R. Youth vaping: A review and update on global epidemiology, physical and behavioral health risks, and clinical considerations. Eur. J. Pediatr. ;1–10. (2022).

Alshanberi, A. M. et al. The prevalence of E-cigarette uses among medical students at Umm Al-Qura university; a cross-sectional study 2020. J. Fam Med. Prim. Care. 10 (9), 3429–3435 (2021).

Iqbal, N. et al. Electronic cigarettes use and perception amongst medical students: a cross-sectional survey from Sindh, Pakistan. BMC Res. Notes. 11, 1–6 (2018).

Bold, K. W. et al. Early age of e-cigarette use onset mediates the association between impulsivity and e-cigarette use frequency in youth. Drug Alcohol Depend. 181, 146–151 (2017).

Yimsaard, P. et al. Gender differences in reasons for using electronic cigarettes and product characteristics: findings from the 2018 ITC four-country smoking and vaping survey. Nicotine Tob. Res. 23 (4), 678–686 (2021).

Yuan, M., Cross, S. J., Loughlin, S. E. & Leslie, F. M. Nicotine and the adolescent brain. J. Physiol. 593 (16), 3397–3412. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP270492 (2015).

Jee, Y-J. Comparison of emotional and psychological indicators according to the presence or absence of the use of electronic cigarettes among Korean youth smokers. Int. Infor Inst. Tokyo. 19 (10A), 4525 (2016).

Liebrenz, M. et al. Adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and nicotine use: a qualitative study of patient perceptions. BMC Psychiatry. 14, 1–11 (2014).

Pericot-Valverde, I., Elliott, R. J., Miller, M. E., Tidey, J. W. & Gaalema, D. E. Posttraumatic stress disorder and tobacco use: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addict. Behav. 84, 238–247 (2018).

Ganson, K. T. & Nagata, J. M. Associations between vaping and eating disorder diagnosis and risk among college students. Eat. Behav. 43, 101566 (2021).

Pérez, A., Bluestein, M. A., Kuk, A. E., Chen, B. & Harrell, M. B. Internalizing and externalizing problems on the age of e-cigarette initiation in youth: findings from the population assessment of tobacco and health (PATH), 2013–2017. Prev. Med. 161, 107111 (2022).

Szoko, N., Ragavan, M. I., Khetarpal, S. K., Chu, K. H. & Culyba, A. J. Protective factors against vaping and other tobacco use. Pediatrics ;148(2). (2021).

Funding

The authors affirm that they received no funding, grants, or other support while preparing this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.M. Conceptualization and methodology writing. A.H. and A.Y. collected the data, A.A data analysis, GH.SH drafted the initial manuscript, F.M. and GH.SH wrote/edit the final version of this article. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ibrahim, F.M., Shahrour, G., Hashim, A. et al. E-cigarette usage and mental health among undergraduate medical and health sciences students. Sci Rep 15, 13169 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94545-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94545-6