Abstract

The tripartite model of emotion regulation (Three Circle Model), comprising threat, drive, and soothing systems, underpins Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT). These systems are implicated in experiences of emotion, motivation, and physiological activation and this model is used within CFT frameworks to assess emotion regulation functioning and assist with case formulation. Despite its importance to CFT, each system is typically gauged using proxy self-report measures of emotion, lacking direct measurement of system interactivity. In this study, we developed and psychometrically tested a novel digital measure of the tripartite model with 311 young adults (aged 18–24, M = 19.6; 223 female, 85 male, 3 non-binary). Here we report that evaluation indicated the measure had good construct validity with other validated self-report measures of emotion, emotion regulation, and mental health. Test-retest reliability of the scale was then established in a second sample with 90 participants (aged 18–24, M = 23.2; 43 female, 46 male, 1 non-binary). These findings support the use of this measure as a brief, dynamic scale that captures central CFT theory and can be easily used with clients or in research contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Numerous meta-analyses indicate support for Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT) as a therapeutic model for the treatment of mental health disorders, as well as for promotion of wellbeing1,2,3. CFT has been applied and evaluated in the context of a variety of clinical disorders and populations, some highly treatment-resistant; these include young offenders with conduct disorders and high levels of callous unemotional traits4,5, clients with eating disorders6and personality disorders7, veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder8, and those with bipolar disorders9. CFT has also been evaluated with non-clinical groups, with research finding the approach significantly reduces stress for those in the community10, reduces self-criticism for parents11, and positively impacts emotional and psychological well-being, significantly increasing flourishing for members of the public12.

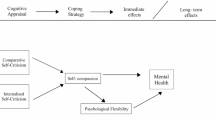

Central to CFT is its underlying theoretical model for emotion regulation, referred to as the tripartite model of emotion regulation or Three Circle Model13. According to this evolutionary informed model, Gilbert and Simos14 posit that humans have three central life tasks which are associated with three domains of emotions that evolved primarily to detect and respond to: (1) threats (the threat system – the red circle), (2) opportunities for resources (the drive system – the blue circle), and (3) opportunities to rest and digest (the soothing system – the green circle). The Three Circle Model is depicted in Fig. 1, which illustrates the motivation, associated emotions, and physiological activity involved in each system.

The Tripartite Model of Emotion Regulation: The Three Circles. Note.From “Essentials of Compassion Focused Therapy: A Practice Manual for Clinicians” by N. Petrocchi, J. Kirby, & B. Baldi, 2024, Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge15. Copyright 2024 by Routledge. Adapted from P. Gilbert (2010). Reprinted with permission.

The threat system (or red circle) is triggered by perceived danger (physical or social) and incentivises humans to avoid harm through employment of protection and defensive behaviours, including fight (e.g., confrontation) and flight (e.g., avoidance). Threat-based emotions that activate these behaviours include fear, anxiety, anger, and disgust12. Physiologically, this system predominantly stimulates sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activity (e.g., increased heart rate), increasing arousal and energy to enable protective behaviours and action16. It has been theorised that, in some instances, the dorsal vagal parasympathetic nervous system can be activated when defence requires immobility17. Although this system is critical for protection, the overactivity or dominance of the threat system in relation to other two systems over time can result in significant prolonged negative affect and can act as a transdiagnostic vulnerability factor for many mental health difficulties13,18.

The drive system (or blue circle), sometimes referred to as the resource-focused system, is a high-arousal positive affect regulation system serving the function of activating humans to seek out and acquire resources to fulfil basic biological needs (e.g., food, shelter, reproduction, social standing). When activated, this system results in a range of positive emotions, such as excitement, happiness, and joy, and is physiologically associated with increased SNS activity19(e.g., increased heart rate). Excess activity or stimulation of this system in proportion to other systems may result in elevated goal-directed activity (e.g., hypomania/mania symptoms)13. Additionally, Gilbert13and others20,21 postulate that this system can also be over-relied upon to downregulate threat system activity, often resulting in over-compensatory behaviour, maladaptive perfectionism, and burn-out.

The soothing system (or green circle) is also a positive affect regulation system; however, it is characterised by lower arousal13. The soothing system supports recovery, and relates to emotions such as contentment, calm, peace, and safeness. This system is physiologically different to the drive and threat systems as it is associated with parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) activity, which is often measured using heart rate variability (HRV). This system is associated with higher levels of compassion and resting HRV22. The soothing system helps to regulate the emotional and behavioural activity of the other two systems (drive and threat) through the activation of the parasympathetic system, demonstrated by increased HRV15,23.

Each system can be activated via external and internal stimuli; for example, the threat system will be activated if the subject detects physical danger (e.g., smoke, snake), the drive system by the prospect of an award or promotion, and the soothing system through caring touch, proximity to caregivers, and vocal tones24,25. Equally, internal stimuli, such as what one imagines and thinks about, can also activate these systems, which implicates cognitive processes such as rumination and worry, resulting in increased threat and heightened SNS activity21. In contrast, self-compassionate thinking and imagery can stimulate the soothing system, resulting in increased parasympathetic activity, as well as feelings of contentment and safeness12.

Evidence supporting these three affect regulation systems has relied predominantly on studies measuring their correlates in physiological activity19,12,26, as well as self-report measures27,20,28. For example, research has found that self-compassion can trigger a physiological pattern where there is reduced heart rate and skin conductance (sympathetic indicators), as well as increased parasympathetic activity as measured by HRV; in contrast, rumination can produce the opposite pattern29. Sousa et al.12found in another study that reading vignettes of people in threat, drive, and soothing states also led the participant to experience the expected physiological patterns of decreased HRV in the threat and drive scenarios, and increased HRV in the soothing scenario. In terms of self-report measures, the tripartite model is typically assessed using proxy measures such as the PANAS30(Positive and Negative Affect Schedule) with researchers finding compassion focused interventions increase positive affect and reduce negative affect, reflecting a changing of activation in the tripartite model28,31.

Although these current approaches provide important insights into the tripartite model, gathering physiological data can be effortful and costly23, and may not distinguish between drive and threat activation. Further, while extant self-report affect scales load onto the tripartite model’s three systems, they do not explicitly or directly factor the motivational components of the systems into the formulation of their subscales. The Three Circles Model presupposes motivational aspects by explicitly categorising emotions by their motivational counterparts, and through explicit task instructions. Critically, extant affect measures do not integrate the relational nature of these systems during measurement. The visual heuristic nature of the Three Circles implicitly requires respondents to indicate the relative activation of each system, providing immediate visual feedback, whereas traditional Likert scale questionnaires often treat such systems independently.

The insights provided by the Three Circle Model pertain less to how these systems operate in isolation, but rather how they operate relative to each other21. A common practice employed in CFT is directing clients to draw these systems as circles, with the size of the circle reflecting the dominance of the system (or how much time they feel that system is in control)32,33. Therapists use this assessment information for several purposes: (1) to gauge current emotion regulation dominance, (2) to inform case formulation, and (3) to progress change over time through the course of therapy. Drawing one’s “Three Circles” has high clinical utility, as it is quick, engaging, and does not require a high level of literacy. Moreover, it provides individuals with an easy and de-shaming medium in which to convey emotional experience. Despite clinicians relying on the Three Circles as both psychoeducation and measurement throughout the course of CFT intervention and treatment, there is no standardized measure that directly assesses it34.

To overcome this limitation in measurement and improve the precision in how CFT is assessed in terms of mechanisms, we developed a new digital measure of these systems (which can be freely accessed here: https://threecircles.app/demo). The Three Circles Digital Scale provides clients the opportunity to visualise these systems, as well as re-size them in relation to how they are experiencing them. The individual system scores are formulated based on rated size in comparison to the other systems; this enables researchers, clinicians, and respondents to assess not only each system in isolation, but critically, in relation to each other. Current physiological and self-report scales do not permit this. Furthermore, an instructional video is included with this measure to articulate the relation of emotions to motivations and ensure participants rate their emotions factoring the physiological/motivational component into the experience as opposed to just rating based on positive/negative valence. This measure is comparable to and influenced by other previously validated visual analogue scales, such as those used to assess stress, pain, and overall wellbeing35,36. Having a highly sensitive, digital, visual analogue measure such as this can increase the accuracy and speed with which emotion regulation systems are measured, and can be used to predict the likelihood of psychological distress and difficulties in emotion regulation.

The aim of this study is to psychometrically validate a novel digital visual analogue measure of affect regulation which underpins CFT. We asked participants to complete self-report questionnaires measuring current (Subcomponents of Affect Scale37- SAS) and retrospective (Tripartite PANAS12) affective states (clustered into threat, drive, and soothing emotions), psychological distress (Depression Anxiety Stress Scale38- DASS), and difficulties in emotion regulation (Difficulties with Emotion Regulation Scale39 – DERS-18). The rationale for the inclusion of both current state and retrospective report ratings was to assess the Three Circles in both capturing information about current, transient emotional states via associations with conventional state measures of emotion, as well as self-reported evaluation of recent emotional states via associations with retrospective measures. Participants were asked to resize each circle to reflect their perceived threat, drive, and soothing system activity currently, and over the past week. As the fundamental premise of this measure is that the relative (rather than absolute) size of each circle is indicative of one’s experience, the primary outcome measure was the relative size of each circle expressed as a percentage of total circle area (or circle dominance). Additionally, we measured the imbalance of the Three Circles by calculating the standard deviation of the area across the Three Circles.

We predicted that for both current and retrospective emotions, the relative size of each circle would be positively associated with their respective emotions as measured by the SAS and PANAS, demonstrating convergent validity. Given differences in both valance and arousal, we predicted threat (red circle) size would be negatively associated with self-reported ratings of soothing emotions, and soothing (green circle) size would be negatively associated with threat emotions, further demonstrating convergent validity.

We also predicted that drive and soothing systems (which have different physiological underpinnings, but are similar in terms of affect being positive), would have little to no association, demonstrating divergent validity. Specifically, we predicted that when we examined the correlations between drive circle activity and threat and soothing emotions based on self-report scales (SAS and PANAS), we would find little to no significant association.

We further predicted that higher threat dominance would predict greater difficulties in emotion regulation, as well as clinical distress, as reflected in higher stress, anxiety, and depression scores, and that higher soothing dominance would protect against emotional regulation difficulties and distress, as reflected in lower respective scale scores. This would demonstrate criterion validity of our novel measure with established benchmarks of clinical distress and difficulties with emotion regulation.

Finally, we expected that overall imbalance between the systems (greater standard deviation across circle areas) would be predictive of psychological distress and difficulties in emotion regulation, given the assertions inherent to compassion focused therapy pertaining to systems downregulating each other to prevent a less environmentally appropriate dominance of any one system13.

Results

We examined Bonferroni-corrected pairwise correlations between variables to establish whether the Three Circles measures of circle dominance and circle imbalance could predict scores on measures of affect, difficulties with emotion regulation, and psychological distress. We then examined data regarding the ease-of-use and accessibility of the Three Circles measure through descriptive statistics (available in Table 1).

Current emotion

Bonferroni-corrected bivariate correlations between ratings of current emotional states (state affect scores on the soothing, drive, and threat subscales) and the relative size of each circle (circle dominance) displayed significant, positive associations in line with the hypothesised relationships, demonstrating convergent validity with established measures of intra-system emotion. The relative size of the threat (r(309) = 0.35, p < .001; 95% CI [0.25, 0.44], drive (r(309) = 0.19, p < .001; 95% CI [0.09, 0.30]), and soothing (r(309) = 0.35, p < .001; 95% CI [0.24, 0.44]) circles were significantly and positively associated with their respective state affect subscale scores, reflecting congruence between the two measures of current affective state.

Further significant negative associations between relative circle size and emotional states per ratings on SAS subscale scores were identified, further demonstrating convergent validity. The relative size of the soothing (r(309) = − 0.34, p < .001; 95% CI [ −0.44, −0.24]) and threat (r(309) = − 0.36, p < .001; 95% CI [−0.45, −0.26]) circles were significantly and negatively associated with each other’s respective ratings via the SAS, exhibiting the Three Circles’ ability to differentiate between opposite emotion systems. This was further displayed by threat circle dominance being significantly and negatively associated with ratings of drive on the SAS (though to a lesser degree than its relation to ratings of soothing emotion on the SAS) (r(309) = − 0.20, p < .001; 95% CI [−0.31, −0.09]).

Non-significant correlations between unrelated systems, such as between drive circle size and ratings of threat (r(309) = 0.02, p = .787; 95% CI [−0.10, 0.13]), soothing circle size and ratings of drive (r(309) = 0.05, p = .407; 95% CI [−0.06, 0.16]), and drive circle size and ratings of soothing emotion (r(309) = 0.01, p = .831; 95% CI [−0.12, 0.10]) displayed the ability of the Three Circles to discriminate between emotion systems and its divergent validity (demonstrated through lack of significant association with established measures of unrelated emotion systems). This is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Retrospective emotion

Bonferroni-corrected bivariate correlations between ratings of retrospective emotional states (PANAS scores on the soothing, drive, and threat subscales) and the relative size of each circle displayed significant, positive associations in line with the hypothesised relationships, as shown in Fig. 2, demonstrating convergent validity through positive associations with established measures of emotion within each system. The relative size of the threat (r(309) = 0.42, p < .001; 95% CI [0.32, 0.51]), drive (r(309) = 0.20, p < .001; 95% CI [0.09, 0.30]), and soothing (r(309) = 0.22, p < .001; 95% CI [0.11, 0.32]) systems were significantly and positively associated with their respective PANAS subscale scores, reflecting congruence between the two measures of retrospective affective state.

Additionally, there were significant negative associations found between individual circle ratings and emotional states per ratings on the PANAS, further demonstrating convergent validity. Specifically. the relative size of the soothing (r(309) = − 0.28, p < .001; 95% CI [−0.38, −0.17]) and threat (r(309) = − 0.27, p < .001; −0.37, −0.16]) circles were significantly and negatively associated with each other’s respective ratings via the PANAS, exhibiting the Three Circles’ ability to differentiate between opposite systems.

Divergent validity was exhibited by the lack of association between retrospective drive circle ratings and retrospective ratings of soothing emotion on the adapted PANAS when accounting for the Bonferroni corrected p value of 0.017 (r(309) = 0.11, p = .047; 95% CI [0.00, 0.22]), demonstrating the Three Circles’ ability to differentiate between unrelated constructs despite being similar in emotional valence.

Contrary to predictions, we found the drive (r(309) = − 0.24, p < .001; 95% CI [−0.34, −0.13]) and threat (r(309) = − 0.31, p < .001; 95% CI [−0.41, −0,21]) circles were significantly and negatively associated with each other’s respective ratings via the PANAS, and that the size of the soothing circle was positively associated with ratings of drive via the PANAS (r(309) = 0.19, p < .001; 95% CI [0.08, 0.30]). In these instances the valence is possibly explaining these correlations (drive emotions are opposite valence to threat and the same valence as soothing emotions).

Clinical measures

Bonferroni-corrected bivariate correlations examining how ratings of psychological distress (depression, anxiety, stress) and difficulties in emotion regulation were associated with retrospective threat circle dominance supported hypotheses that criterion validity would be established through positive associations with established benchmarks of clinical constructs. (see Fig. 3). Depression (r(309) = 0.39, p < .001; 95% CI [0.29, 0.48]), anxiety (r(309) = 0.39, p < .001;95% CI [0.29, 0.48]), stress (r(309) = 0.44, p > .001; 95% CI [0.35, 0.53]), and difficulties with emotion regulation (r(309) = 0.37, p < .001; 95% CI [0.27, 0.46]) were all associated with relative threat circle size, reflecting the dominance of threat-based emotion associated with these constructs and the threat system’s criterion validity (established through positive associations with established criterion variables). Similarly, retrospective soothing circle dominance was negatively associated with depression (r(309) = − 0.23, p < .001; 95% CI [−0.34, − 0.013]), anxiety (r(309) = − 0.25, p < .001; 95% CI [−0.35, −0.14]), stress (r(309) = − 0.37, p > .001; 95% CI [−0.46, −0.27]), and difficulties with emotion regulation (r(309) = − 0.24, p < .001; 95% CI [−0.34, −0.13]), exhibiting the mitigating effects of the soothing system upon psychopathology. The impeded drive activity inherent to depression was reflected in retrospective drive circle dominance negatively correlating with ratings of depression (r(309) = − 0.25, p < .001; 95% CI [−0.35, −0.14]).

Contrary to predictions, we found no evidence for imbalance (retrospective rating) being associated with depression (r(309) = − 0.02, p = .706; 95% CI [−0.13, 0.09]), anxiety (r(309) = 0.04, p = .524; 95% CI [−0.08, 0.15]), stress (r(309) = − 0.04, p = .458; 95% CI [−0.15, 0.07]), or difficulties with emotion regulation (r(309) < 0.01, p = .997; 95% CI [−0.11, 0.11]) and thus the criterion validity of the imbalance variable was not established. Also contrary to predictions, we found negative associations between retrospective drive circle activity and ratings of anxiety (r(309) = − 0.23, p > .001; 95% CI [−0.33, −0.12]), stress (r(309) = − 0.17, p = .002; 95% CI [−0.28, −0.06]), and difficulties with emotion regulation (r(309) = − 0.22, p < .001; 95% CI [−0.32, −0.11]).

We then ran additional exploratory analyses using current Three Circles measures instead of retrospective ratings to examine the relationship with psychological distress and difficulties with emotion regulation. Depression (r(309) = 0.34, p < .001; 95% CI [0.23, 0.43] ), anxiety (r(309) = 0.39, p < .001; 95% CI [0.29, 0.48]), stress (r(309) = 0.37, p < .001; 95% CI [0.27, 0.46]), and difficulties with emotion regulation (r(309) = 0.29, p < .001; 95% CI [0.18, 0.39]) were all associated with current threat circle dominance. Furthermore, current soothing circle dominance was negatively associated with depression (r(309) = − 0.21, p < .001; 95% CI [−0.32, −0.10]), anxiety (r(309) = − 0.34, p < .001; 95% CI [−0.44, −0.24]), stress (r(309) = − 0.39, p < .001; 95% CI [−0.48, −0.29]) and difficulties with emotion regulation (r(309) = − 0.22, p < .001; 95% CI [−0.33, −0.11]). We found that impeded drive inherent to depression was again reflected in findings, with current drive circle activity significantly, negatively associated with depression (r(309) = − 0.15, p = .011; 95% CI [−0.25, −0.03]). However, we found no relationship concerning current imbalance between the circles and ratings of depression utilising the Bonferroni corrected p value of 0.013 (r(309) = − 0.12, p = .041; 95% CI [−0.22, −0.01), anxiety (r(309) = − 0.09, p = .136; 95% CI [−0.19, 0.03]), stress (r(309) = − 0.08, p = .143; 95% CI [−0.19, 0.03]) or difficulties with emotion regulation (r(309) = − 0.12, p = .028; 95% CI [−0.23, −0.01]).

Study 2

Having established convergent and divergent validity, as well as the criterion validity of threat dominance with established measures of clinical distress, we recruited 90 participants via the online platform Prolific (aged 18–24, M = 23.2, SD = 1.57) to complete a test-retest version of the study (43 female, 46 male, 1 otherwise specified). Methodology of this study was the same as in Study 1, except participants completed the study twice, with a week-long break between data collection. We examined correlations between test and retest ratings of individual circle dominance for current and retrospective ratings of the Three Circles.

We found significant positive associations between test and retest ratings of current emotion via Three Circles dominance, as shown in Table 2. This was also the case for retrospective ratings of emotion via the Three Circles, with the exception of the drive circle.

This is consistent with the findings in Study 1 regarding retrospective ratings of the drive circle, which implied that participants appeared to be less reliable in retrospective ratings of activated positive emotion. We found test-retest correlation averages of 0.43 for current ratings of the Three Circles, and 0.33 for retrospective ratings; correlations between 0.40 and 0.75 are defined as good40. Despite the likelihood of emotions fluctuating over the break period, these results provide evidence for test-retest reliability of real-time ratings of emotion via the Three Circles.

Discussion

We assessed whether a digital adaptation of a common therapeutic tool – sizing circles to reflect subjectively experienced activation of the three affective motivational systems of Gilbert’s Tripartite Model – would hold reliable and valid psychometric properties as a novel measure of emotion. Using only a brief introductory explanation of the Tripartite Model relating emotions and motivations in colloquial terms, participants were asked to resize circles representing threat, drive, and soothing systems to reflect their current and recent affective experiences. As a heuristic means of categorizing the most pertinent experienced affective states of respondents visually and relatively, we predicted that the relative size of each circle (as a proportion of total circle area, or circle dominance) reflecting the activity of individual systems would be positively associated with scores on traditional Likert-scale measures of affect gauging categorical affective states aligned with the function of each system, reflecting convergent validity through positive correlations with established measures of congruent emotion. We also predicted negative relationships between individual circle dominance and emotion ratings of opposite systems via self-report scales, which would further contribute to convergent validity of the measure. Additionally, we predicted little to no relationship between individual circle dominance and emotion ratings of incongruent systems via self-report scales, reflecting divergent validity of the measure.

Based on the results, our predictions were almost all supported. When asking participants to size each circle based on their current emotional state, the relative size of each circle (circle dominance) was positively and significantly correlated with ratings of current emotion on the respective matching subscales of the SAS, demonstrating convergent validity. In addition, threat circle dominance was negatively associated with ratings of soothing-related emotions on the SAS, and similarly, soothing circle dominance was negatively associated with ratings of threat-related emotions on the SAS, reflecting the relational nature of the scale (one system serving to downregulate the other) and demonstrating convergent validity. This was expected as threat and soothing emotions differ in both the valence and arousal. Of note, threat circle dominance was negatively associated with ratings of drive-related emotions on the SAS, while drive circle dominance did not display a similar relationship with threat-related emotions. The lack of results for drive circle dominance with threat-related emotions indicates some divergent validity, as the drive system does not work in opposition to the threat system in the same way as the soothing system does (different physiological underpinnings)41. This is further established by soothing and drive ratings not correlating with each other (despite being of the same valence).

These patterns of results were largely repeated for the retrospective PANAS scores, with threat and soothing dominance scores associated significantly and as predicted. Further, we also found that drive circle dominance was positively related to retrospective ratings of soothing emotions on the PANAS, and threat circle dominance was negatively related to retrospective ratings of drive-based emotion on the PANAS. Although not predicted, these patterns are in line with the proposition that drive and soothing are positively valanced, and threat and drive have opposing valence.

While the pattern of results slightly differed between the retrospective and current appraisals for the drive system, it is important to recognise the affective adjectives used for the SAS and the PANAS also differ. This was most prominent for the drive system where the SAS included items such as “full of pep” and “lively” where the PANAS items were “excitement” and “pleasure”. The SAS items appear focused on heightened arousal of drive-related emotions, which might explain the divergence from the soothing system. In contrast, PANAS items are more focused on positive valence, which may explain the association with soothing-related emotions which share a similar positive valence. These slight differences between current and retrospective assessments reinforce the specificity inherent in adjective-based self-report psychometric scales, while the Three Circles represents a robust approach to capturing salient emotions experienced by respondents.

When we examined associations between retrospective Three Circles measures and ratings of psychological distress and difficulties with emotion regulation, we found that imbalance was not predictive of either of these outcome variables and thus not an effective metric of the relational nature of the systems, but that the outcome variables were reliably positively correlated with negative emotion (threat), and negatively correlated with positive emotion (drive and soothing). Therefore, we found that dominance was an effective metric of the relational nature of the systems and that the relationship between the threat and soothing systems specifically was indicative of psychological distress and difficulties with emotion regulation, demonstrating criterion validity. When interpreting these results, a non-static optimum balance between the circles makes more theoretical sense than the assumption that there is a perfect baseline level of balance between the circles. Gilbert13 postulated that affiliative (soothing) emotions are the most effective at downregulating threat-based emotions, which are characteristic of psychological distress and difficulties with emotion regulation, with the emotion systems serving to incentivise behaviour within environmental context. Long-term balance between the systems would not be predictive of psychological distress or difficulties with emotion regulation because the systems should be continually compensating for environmental context, and the drive system is often ineffective at downregulating threat. However, participant competency at downregulating threat-based emotions by activating the soothing system would be predictive of the likelihood of experiencing difficulties.

When examining real-time Three Circles scores with psychological distress and difficulties with emotion regulation we found similar patterns, however, not for the drive system. Drive system dominance was negatively associated with depression on the DASS, but not for anxiety, stress or with difficulties in emotion regulation. This is theoretically intuitive; major depressive disorder is characterised by impeded motivation and lack of positive emotions (anhedonia).

We also established test-retest reliability of the Three Circles, with satisfactory correlations between ratings from the first testing and ratings from the second time participants completed the survey; this was also the case for retrospective ratings, aside from the drive circle, which did not correlate. This may further explain the unexpected cross-correlations obtained in the first study, with participants appearing to be less adept at retrospectively differentiating between types of positive emotion.

The findings from this study indicate that the Three Circles Digital Scale is a reliable and valid measure of Gilbert’s Tripartite Model of emotion regulation systems, which forms the theoretical basis of CFT. The visual, relational nature of this measure has the particular advantage of inherently measuring the relative subjective representation of each system. By avoiding the use of individual adjectives, specific descriptive sentences, or other language-based items as is typical in extant psychometric scales, we argue that the Three Circle measure represents subjective reports of current or recent states that are not biased by weighting of irrelevant item descriptors, focusing on the most salient states represented by each system. The concurrent and intuitive response modality is ideal for longitudinal, repeated measurement, and may be especially advantageous for methodology such as experience sampling, organisational/occupational settings, or in younger populations where time and language restrictions pose significant barriers to data collection.

The Three Circles Digital Scale has immediate application and appeal for CFT therapists to not only use as a key form of assessment with clients, but also to inform case formulations. Specifically, the nature of the visual measure enables reflective questions regarding what led to the size of the circles being large or small. In addition, the size of the circle can also indicate whether a client feels they have knowledge and skill acquisition on how to grow that system (e.g., whether the client has skills to develop and grow their drive or soothing systems). Moreover, as suggested by Petrocchi et al.33, the CFT therapist can guide clients to do ‘Three Circle Check-Ins’ pre and post CFT exercises; before and after a compassion meditation or breathing exercise, for example. In this way, the Three Circles measure acts as an immediate visual analogue scale, providing feedback on client experience. Indeed, in almost all therapeutic models (e.g., Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy) emotion regulation is central42, and thus the Three Circles could be applied in almost all therapy modalities as way to assess for emotion, emotion regulation, and clinical distress. The Three Circles also allows for direct measurement of the theory underpinning CFT, and thus can be used in CFT evaluations to determine whether shift in system dominance is the key mechanism leading to the changes in self-criticism, shame, self-compassion or clinical outcomes such as depression, anxiety and stress.

A major positive implication of the Three Circle measure is that it provides a shared language of emotional experience that can be used between the therapist and client, which is de-shaming. Many individuals who seek therapy have difficulties with emotional language and describing their emotional states. Moreover, clients can feel ashamed of being angry, anxious, or fearful. Thus, the Three Circle language of red, blue, and green circles can be an intuitively accessible and de-shaming way for clients and therapists to explore their emotional experience. Further, in conjunction with therapeutic skill building, pairing verbal emotional terms with the visual of the Three Circles may support a greater understanding of the variations within emotional experiences, which could in turn support a more nuanced retrospective differentiation and recall of positive emotional experiences. Extending on this, given the Three Circles measure is effectively a digital and interactive one-item scale, it may also be more appropriate for populations with low emotional or verbal literacy, younger populations, and populations with reduced capacity for attention or increased test-fatigue. However, these areas require further research.

The Three Circles Digital Scale demonstrates potential to extend beyond the traditional therapeutic environment and offer support across a wide range of settings, from education with students and teachers34,43, to health with doctors and nurses, disability and support services, nursing homes, or any setting where emotional experience is important, such as in organisational settings with leaders, or in sporting contexts with athletes and coaches44. The shared emotional language fostered from the Three Circles can extend across ecological contexts, raising awareness of the ongoing modulation of systems in relation to the circumstances individuals find themselves in. With ongoing high-level demand for emotional and mental health support, difficulties accessing mental health professionals when needed45,46and the increased uptake in digital mental health supports in recent years47,48, the Three Circles Digital scale represents a low-cost, brief, novel and accessible option to drive emotion awareness, compassion, and screen for emotion regulation and clinical distress.

Despite the positive implications of this research, there are some notable limitations. First, the sample we recruited was from a WEIRD background; thus, examining it with other culturally and linguistically diverse populations and socio-economic statuses would be helpful in further validating its use with other diverse samples. The sample were also all psychology students, and as such may have had primed knowledge and interest in this space, thus future research with populations not from an allied health background or with no prior knowledge could be useful. Extending on this, our recruited sample were not a clinical population; future research could examine the use of the Three Circles scale with clinical disorders (such as mood or anxiety disorders) to determine its use in these different clinical populations. Furthermore, we did not include colourblind participants in this study due to the chromatic nature of the Three Circles (red, blue and green circles). Future research could modify the Three Circles such that they are colourless but include the label as text within each circle – threat, drive and soothing. An alternative solution could also be to use non-chromatic pattern differentiation between circles (e.g., patterns or shading). We recommend testing these approaches to determine if the scale operates in the same way with these variations for those who are colourblind. Although the instructional video explains how emotions and motivations are related, the task instructions do not explicitly ask to indicate motivational strength, and therefore the theoretical model and educational component only indirectly measure motivations. We also found the imbalance variable not to be predictive of psychological distress and difficulties with emotion regulation and thus not to represent clinically significant patterns of distress. Consequently, we advise against use of the imbalance variable until further research investigates the relationship between the threat and soothing systems and if an alternative calculation of the variable might be predictive of clinical distress, given the consistency with which we found that a dominant threat system and subordinate soothing system was predictive of psychological distress and difficulties with emotion regulation.

A further potential limitation on the interpretation of our findings is due to the large proportion of missing data. Technical difficulties in our initial data collection platform led to failures in linking participant data. This may have impacted sensitivity, as we could not analyse the data of the participants to whom this applied. Critically, this data was not missing systematically, and so is unlikely to have biased the study in any way. Despite the impacted sensitivity, we still obtained significant results supporting the use of this measure. The final dataset was not missing data to an extent to impact the pattern of results in any way, and the cause of the missing data was identified and found not to be dependent on study variables or extraneous variables other than the redirect issue (see Figures S2 to S5 of Supplementary Materials for further details).

The theoretical underpinnings of the tripartite model connects the threat and drive systems with sympathetic nervous system activity, and the soothing system with parasympathetic nervous system activity; however, we did not include measures of physiology. Future research should examine physiology using heart rate variability to determine if circle dominance in the scale reflects physiology, which would further support the theory underpinning the model. Future research is also warranted to further delineate patterns of circle dominance. We found unexpected relationships, such as negative correlations between drive and threat system measures, limiting our findings regarding divergent validity. While we speculate that this may have occurred due to the opposite valence associated with drive (positive) and threat (negative) system emotions used in our self-report scales, it nevertheless represents a potential limitation of the discriminability of the Three Circles measure. Further testing of divergent validity is recommended, potentially using measures focused less on emotional valence and with greater focus on motivational aspects of the three systems. Alternatively, physiological measures of autonomic activity such as heart rate variability may prove valuable in discriminating between different circle dominant states49. Finally, we did not include measures of self-compassion, self-criticism or shame, which are central targets in CFT. Future research should examine how the Three Circles Digital Scale correlates with these key constructs; high soothing dominance should correlate with higher self-compassion, and higher threat dominance should associate with higher levels of self-criticism and shame.

The Tripartite Model of Affect Regulation is central in CFT, and we demonstrated the psychometric validity of a new digital measure of the Three Circles. The results from this study indicated the Three Circles scores, as reflected in system dominance, particularly of the threat and soothing systems, predicted emotion, emotion regulation and psychological distress. The measure can be used both in terms of ‘real-time’ and in retrospective ‘the last week’ time references, and offers enormous clinical utility for therapists and clients, particularly when using CFT or when emotion regulation is central to client wellbeing. Overall, the results of this study indicate that the Three Circles is a reliable, valid, and accessible measure of the emotional systems central in CFT. Moreover, this new digital measure is more engaging, appealing, and less burdensome than traditional self-report scales, and thus has high appeal for a range of populations where test-fatigue, emotional and linguistic literacy, and attentional drop-off are experienced.

Methods

Study 1

Participants

We recruited 449 participants to take part in the study. After removing incomplete responses, our final sample consisted of 311 (aged 18–24, M = 19.6, SD = 1.76; 223 female, 85 male, 3 non-binary/unspecified) undergraduate students from the University of Queensland’s human research participation scheme, composed of students enrolled in first-year psychology courses who choose to participate in research for course credit. Participants were advised to only partake in the study if they were aged 18–24 due to the focus on application of the new measure to a young demographic; an additional exclusion criterion advising participants to only complete the study if they could differentiate colour was also specified, due to the colour-coding of circles in the new measure. No further exclusion criteria were specified, as theory indicated that the new measure should be widely appropriate, and no other factors appeared to negatively influence suitability for specific populations. Further demographic information is available in Table S1 of Supplementary Materials; demographical information for Study II is available in Table S3 of Supplementary Materials.

The target sample size was set at 300 participants as this is sufficient in most cases to accurately observe relationships for validation50. We also ran a priori power analyses for bivariate correlations to confirm this was sufficient, factoring in Bonferroni corrections necessary to run correlations on multiple criterion variables while avoiding artificially inflating the possibility of a Type I Error. The analyses between each circle and the three criterion variables inherent to the conventional emotion scales (threat, drive, and soothing) necessitated a Bonferroni correction of 0.017 (0.05/3 = 0.0167), with the analyses upon the distress measures (depression, anxiety, stress, and difficulties with emotion regulation) requiring a Bonferroni correction of 0.013 (0.05/4 = 0.0125). A total sample size of 118 was required to detect a medium effect at 80% power with an α of 0.013, (our most conservative Bonferroni correction).

Procedure

Participants provided consent and completed the questionnaire online via an advertised URL link. Participants first provided brief demographic information followed by responses to the Subcomponents of Affect Scale (SAS), which asks about emotions experienced that day, and then the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS), which asks to participants to rate how they had been feeling over the past week. Following this, they completed the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS) and Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS), which once again asked about experiences specifically over the past week. The SAS and PANAS were utilised to examine convergent validity of the Three Circles via significant correlations between equivalent or opposite emotion systems, and divergent validity through lack of association between non-related emotion systems. The DASS and DERS were utilised to establish the criterion validity of the threat dominance variable and overall imbalance variable through positive associations with these established measures of clinical distress. Several additional measures not relevant to this study were also completed at this timepoint.

Following these scales, participants were asked to read written information pertaining to the nature of the tripartite model of emotion and motivation, before watching an educational video on this model. They were then redirected to the Three Circles Digital Measure, where they were asked to resize the Three Circles to reflect firstly how they were feeling “right now” and then a second time to reflect how they felt “over the past week”. Further information is available in the Supplementary Methods section of Supplementary Materials.

Measures

Demographics

Participants were asked to report their gender (female, male, unspecified), age, education level, ethnicity, and Socio Economic Status (SES). A summary of demographic details is available in Table 2 of Supplementary Materials; demographical information for Study II is available in Table S3 of Supplementary Material.

Current affect

The Subcomponents of Affect Scale37 (SAS) is an 18-item measure of emotion where participants are asked to rate the accuracy with which certain adjectives describe how they are feeling “right now” from 0 (not at all accurate) to 4 (extremely accurate). The SAS is composed of six subscales, first divided based on positive and negative valence, and then further subdivided within each valence with two subscales for high arousal and one for low arousal emotions. In this study we utilised the subscales most aligned with the three emotion systems under investigation – the vigour subscale was used as the equivalent of the drive system; the calm subscale was used for soothing system; and the combined negative subscales were used for the threat system. Items for the threat scale included sad, unhappy, depressed, on edge, tense, nervous, hostile, angry, and resentful. Items for the drive scale were full of pep, lively, and energetic. Items for the soothing subscale were calm, at ease, and relaxed.

Jenkins et al.37 found some unequal factor loadings between items and item covariance, so they utilised McDonald’s ω to assess internal consistency as it is more robust under these conditions than Cronbach’s α. They found 7-day average ωs of 0.84 for the threat subscale, 0.93 for drive, and 0.85 for soothing; in this study, we found McDonald’s ωs of 0.93 for threat, 0.94 for drive, and 0.94 for soothing and Cronbach’s α values of 0.93 for threat, 0.94 for drive, and 0.94 for soothing for the main sample. For the test-retest study, we found McDonald’s ωs of 0.93 for threat, 0.95 for drive, and 0.93 for soothing for the first trial and 0.94 for threat, 0.95 for drive, and 0.96 for soothing for the second trial. We found Cronbach’s α values of 0.93 for threat, 0.95 for drive, and 0.93 for soothing in the first trial, and 0.94 for threat, 0.95 for drive, and 0.96 for soothing in the second trial. Average McDonald’s ωs across the study were 0.93 for threat, 0.95 for drive and 0.94 for soothing; average Cronbach’s α values were 0.93 for threat, 0.95 for drive, and 0.94 for soothing.

Theory regarding the subdivision of affect based on the tripartite model may explain inconsistencies in Jenkins et al.’s factor loadings and item covariance37; they experienced poorer fit with the wellbeing subscale, which may be due to this subscale not specifically reflecting activity of either of the two systems responsible for positive emotion postulated by the tripartite model. Due to the omission of this subscale, these inconsistencies were not deemed to be an issue for the use of the SAS in this study. The convergent validity of this scale with other established measures has been established through use in clinical studies37,20,51.

Retrospective affect

The original Positive and Negative Affect Schedule30 (PANAS) is a 20-item measure to establish retrospective experiences of positive and negative affect over the previous two weeks. There are two 10-item scales, each corresponding to positive or negative emotions. We used an adapted 16-item version of this scale proposed by Sousa et al.12which recategorized items into positive activated (drive) and positive safe/content (soothing) subscales, and incorporated items from the Activation and Safe/Content Affect Scales52. Participants rated the extent to which they felt a certain emotion over the past week (e.g. anger) on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = “not intensely at all”, 6 = “extremely intensely”). Items for the threat subscale included anger, shame, sadness, fear, and anxiety. Items for the drive subscale were excitement, energy, pleasure, vitality, and enthusiasm. Items for the soothing subscale were safeness, happiness, tranquillity, calmness, satisfaction, and contentment.

Sousa et al.12 found their adapted scale demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency, with Cronbach’s α of 0.83 for the threat subscale, 0.84 for the drive subscale, and 0.85 for the soothing subscale. For the main study, our Cronbach’s α estimates were 0.81 for the threat subscale, 0.92 for the drive subscale, and 0.86 for the soothing subscale and our McDonald’s ω estimates were 0.81 for the threat subscale, 0.92 for the drive subscale, and 0.87 for the soothing subscale. For the test-retest study, we found Cronbach’s α values of 0.88 for threat, 0.92 for drive, and 0.86 for soothing for the first trial and 0.88 for threat, 0.92 for drive, and 0.89 for the second trial. We obtained McDonald’s ω estimates of 0.88 for threat, 0.93 for drive, and 0.88 for soothing in the first trial, and 0.88 for threat, 0.93 for drive, and 0.90 for soothing in the second trial. Average Cronbach’s α values across the study were 0.86 for threat, 0.92 for drive, and 0.87 for soothing; average McDonald’s ω estimates were 0.86 for threat, 0.93 for drive, and 0.88 for soothing. The validity of the original PANAS, the Activation and Safe/Content Affect Scales, and adapted version used by Sousa et al.12has been established through use with clinical populations and relations with other established measures12,30,50.

Psychological distress

The DASS-21 is a condensed version of the original 42-item Depression Anxiety Stress Scale, used to measure psychological distress38,53. It consists of three subscales structured to reflect the underlying factors of depression, anxiety and stress, with seven items in each. Participants rated the extent to which they agreed with the items over the previous week on a Likert scale from 0 to 3, with 0 indicating the item did not apply to them at all, and 3 indicating that the item applied to them “very much of the time, or most of the time”. An example of an item from the depression subscale is “I found it difficult to work up the initiative to do things”. An example from the anxiety subscale is “I experienced trembling in the hands”. An example from the stress subscale is “I found it hard to wind down”.

Norton54 found it was a reliable measure of psychological distress across different racial groups, with overall Cronbach’s αs of 0.82 for depression, 0.78 for anxiety, and 0.87 for stress. Our Cronbach’s αs were 0.91 for depression, 0.87 for anxiety, and 0.84 for stress in the main study; we obtained McDonald’s ωs of 0.90 for depression, 0.87 for anxiety, and 0.84 for stress. For the test-retest study, we obtained Cronbach’s αs of 0.96 for depression, 0.88 for anxiety, and 0.91 for stress in the first trial and 0.95 for depression, 0.89 for anxiety, and 0.92 for stress in the second trial. We obtained McDonald’s ωs of 0.96 for threat, 0.89 for drive, and 0.91 for stress in the first trial and 0.95 for depression, 0.90 for anxiety, and 0.92 for stress in the second trial. Average Cronbach’s α values across the study were 0.94 for depression, 0.88 for anxiety, and 0.89 for stress; average McDonald’s ωs were 0.94 for depression, 0.89 for anxiety, and 0.89 for stress.

Lovibond and Lovibond38 found greater separation in factor loadings between constructs in comparison to previously established measures of depression and anxiety, and Antony et al.52 found that the scales were able to effectively differentiate between patients based on symptoms of mental disorders, demonstrating construct validity.

Difficulties with emotion regulation

The DERS-1843is a short-form of the original 41-item Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale proposed by Gratz and Roemer55to assess levels of emotion dysregulation. Participants rated the frequency with which they had a certain emotional experience over the past week on a 5-point Likert scale, with a rating of 1 reflecting that the statement was almost never applicable (0–10%), and a rating of 5 reflecting that the statement was always applicable (91–100%). The scale is composed of six subscales, but can be treated as a general measure of difficulties in emotion regulation without analysing subcomponents. Gratz and Roemer55found satisfactory internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and construct validity of their original measure with a Cronbach’s α of 0.93 for the overall scale; our Cronbach’s α estimate was 0.90, with a McDonald’s ω of 0.91 for the main study. For the test-retest study, we obtained a Cronbach’s α of 0.93 for the first trial and 0.94 for the second study; we obtained McDonald’s ω estimates of 0.93 for the first trial and 0.94 for the second trial. The average Cronbach’s α estimate across the study was 0.93; the average McDonald’s ω estimate was 0.93. Victor and Klonsky39 obtained an internal consistency estimate of 0.91 for the DERS-18, and found the scale could predict clinically significant behavioural outcomes (e.g., self-harming behaviour), demonstrating criterion validity.

Three circles digital scale

The theoretical model underpinning the Three Circles described previously is central in Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT). When using CFT with clients, therapists will provide psychoeducation on the Three Circles and then invite the client to draw their own three circles. Therapists instruct the client to draw the three circles either as a state-based measurement (e.g. “What are your three circles now?”) or as a retrospective measurement (e.g. “How have your three circles been over the last week?”). Clients are asked to draw the circles so that the size that reflects how dominant that circle is/was for them during the specified period32,33. The circles are colour coded, with the threat circle being red, the drive circle blue, and the soothing circle green. The information obtained through asking the client to complete the Three Circles then guides both assessment and case formulation in CFT.

The Three Circles Digital Scale is a novel, digitised, algorithmic measure based on this circle drawing practice and other visual analogue scales35,36. This measure serves to establish dominance of the three systems, as each system is assessed not individually, but relative to each other. It is postulated that imbalance between these systems leads to greater psychological distress, whereas balance between the systems reflects optimal emotion regulation. For example, in Supplementary Fig. 1 of Supplementary Materials, Panel A shows the client has a large red circle, with small blue and green circles, indicating the client has experienced greater levels of threat with little drive and soothing activity, whereas in Panel B, the client exhibits large levels of threat and drive activity, with an underactive soothing system, indicating the client regulates threat emotions primarily through the drive system.

The area measurement of each circle was calculated via the conventional formula (\(\:A=\pi\:{r}^{2}\)), with A representing the circle’s area and r indicating the individual circle’s radius. Individual circle dominance was then calculated using the formula D = A/(ΣC), with D constituting a respective circle’s proportion of all circle areas, A representing the individual circle’s area, and ΣC referring to the sum of all circles’ area. An individual circle’s dominance score was interpreted as representing the percentage of the overall Three Circles area that this circle contributed to; for example, if the threat circle’s dominance score was 0.33, this was interpreted as the threat circle comprising 33% of overall Three Circles area.

Dominance scores can theoretically range between 0 and 1, with a score of 0 indicating no activity of that system and a score of 1 indicating the system is extremely active. Each system has a dominance score, as they are calculated in relation to each other. The average dominance scores per system (along with confidence intervals) are included in Table 2, and within our sample, participants provided dominance ratings that ranged from 0 to 1. Overall system imbalance scores were constructed by calculating the standard deviation across the area scores of all three circles according to the formula:

Where \(\:{x}_{i}\) corresponds to the area of circle i, \(\:\stackrel{-}{x}\) is the average of all circle areas, and n = 3 (for three circles). A score of 0 indicates perfect balance between the circles, and higher scores reflect greater imbalance. The range of possible system imbalance scores starts at 0, representing complete balance between the systems (dominance ratings of 0.33 rated for each system equally). Higher imbalance scores indicate less balance between the systems, with a certain system or systems primarily representing the emotional experience compared to another or others. In this study, we obtained imbalance scores ranging from 0 (perfectly balanced) to 5.85 (the most extreme imbalance reported).

We predicted The Three Circles to be a more efficient and less time-consuming measure compared to traditional Likert-scales, with the potential to mitigate issues with language comprehension, alexithymia or the inability to identify particular emotions, to encapsulate the relative nature of the emotion systems.

Data cleaning and analytic strategy

The overall analytic strategy consisted of examining Bonferroni-corrected pairwise correlations between dominance and balance scores on the Three Circles measure with conventional ratings of affect, psychological distress, and difficulties in emotion regulation. The rationale for this was that dominance scores correlating with conventional measures of emotion would establish construct validity of the Three Circles at measuring emotion, and imbalance ratings correlating with measures of psychological distress and difficulties with emotion regulation would establish criterion validity with metrics of emotional imbalance/difficulties.

Chi square tests of independence were initially run to establish that participants were not missing data systematically based on categorical demographic variables. A chi square test of independence established that participants were not more likely to be missing data based on gender, X22 (2, N = 449) = 0.66, p = .718. They were also not more likely to be missing data based on ethnicity, X22 (4, N = 449) = 1.60, p = .808. Spearman’s rank correlations were utilised to examine whether data were missing systematically based on ordinal variables; participants were not more likely to be missing data based on age or education, but lower SES participants were more likely to be missing data. This can be viewed in Supplementary Table 2 of Supplementary Materials.

Consequently, we ran another Spearman rank correlation to establish whether participants were more likely to have refrained from completing the Three Circles due to SES; this analysis established that SES did not predict whether a participant completed the Three Circles, rs(447) = 0.02, p = .745. As such, we could infer that SES did not appear to be a factor in the suitability of our measure, and low SES participants were not more likely to have dropped out entirely, or because of the measure. Further details including multiple imputation sensitivity analysis are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Study 2

Methodology of this study was the same as in Study 1, except participants completed the study twice, with a week-long break between data collection. We examined correlations between test and retest ratings of individual circle dominance for current and retrospective ratings of the Three Circles.

Data availability

The dataset generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available on the Open Science Framework at the following link: https://osf.io/b8zdv.

References

Millard, L. A., Wan, M. W., Smith, D. M. & Wittkowski, A. The effectiveness of compassion focused therapy with clinical populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 326, 168–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.01.010 (2023).

Petrocchi, N. et al. The Impact of compassion-focused Therapy on Positive and Negative Mental Health Outcomes: Results of a Series of Meta-analyses (Science and Practice. Advance online publication, https://doi.org/10.1037/cps0000193 (2023).

Vidal, J. & Soldevilla, J. M. Effect of compassion-focused therapy on self‐criticism and self‐soothing: A meta‐analysis. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 62 (1), 70–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12394 (2022).

Ribeiro da Silva, D., Rijo, D., Castilho, P. & Gilbert, P. The efficacy of a compassion-focused therapy–based intervention in reducing psychopathic traits and disruptive behavior: A clinical case study with a juvenile detainee. Clin. Case Stud. 18 (5), 323–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534650119849491 (2019).

Ribeiro da Silva, D. et al. The efficacy of the PSYCHOPATHY.COMP program in reducing psychopathic traits: A controlled trial with male detained youth. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 89 (6), 499–513. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000659 (2021).

Vrabel, K. R. et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy versus compassion focused therapy for adult patients with eating disorders with and without childhood trauma: A randomized controlled trial in an intensive treatment setting. Behav. Res. Ther. 174, 104480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2024.104480 (2024).

Lucre, K., Ashworth, F., Copello, A., Jones, C. & Gilbert, P. Compassion focused group psychotherapy for attachment and relational trauma: engaging people with a diagnosis of personality disorder. Psychol. Psychotherapy: Theory Res. Pract. Advance online publication, https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12518 (2024).

Romaniuk, M. et al. Compassionate Mind training for ex-service personnel with PTSD and their partners. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 30 (3), 643–658. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2825 (2023).

Gilbert, P. et al. Compassion focused group therapy for people with a diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder: A feasibility study. Front. Psychol. 13, 841932. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.841932 (2022).

Irons, C. & Heriot-Maitland, C. Compassionate Mind training: an 8‐week group for the general public. Psychol. Psychotherapy: Theory Res. Pract. 94 (3), 443–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12320 (2020).

Kirby, J. N., Hoang, A. & Ramos, N. A brief compassion focused therapy intervention can help self-critical parents and their children: A randomised controlled trial. Psychol. Psychotherapy: Theory Res. Pract. 96 (3), 608–626. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12459 (2023).

Sousa, R., Petrocchi, N., Gilbert, P. & Rijo, D. HRV patterns associated with different affect regulation systems: sex differences in adolescents. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 170 (1), 156–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2021.10.009 (2021).

Gilbert, P. The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 53 (1), 6–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12043 (2014).

Gilbert, P. & Simos, G. Compassion Focused Therapy: Clinical Practice and Applications (Routledge, 2022).

Petrocchi, N. & Cheli, S. The social brain and heart rate variability: implications for psychotherapy. Psychol. Psychotherapy: Theory Res. Pract. 92 (2), 208–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12224 (2019).

Fredrickson, B. L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 56 (3), 218 (2001).

Porges, S. W. The polyvagal perspective. Biol. Psychol. 74 (2), 116–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.06.009 (2007).

Scheid, D. & Singh, F. Can compassion focused therapy enhance dual recovery for veterans? Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 42 (3), 329. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000346 (2019).

Depue, R. A. & Morrone-Strupinsky, J. V. A neurobehavioral model of affiliative bonding: implications for conceptualizing a human trait of affiliation. Behav. Brain Sci. 28 (1), 313–395. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0140525x05000063 (2005).

Kelly, A. C., Zuroff, D. C., Leybman, M. J. & Gilbert, P. Social safeness, received social support, and maladjustment: testing a tripartite model of affect regulation. Cogn. Therapy Res. 36 (6), 815–826. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-011-9432-5 (2012).

Kirby, J. N. & Petrocchi, N. Compassion focused therapy – What it is, what it targets, and the evidence. In: Finlay-Jones, A., Bluth, K., Neff, K. (eds) Handbook of Self-Compassion. Mindfulness in Behavioral Health. Cham, Switzerland; Springer, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-22348-8_23 (2023).

Di Bello, M. et al. The compassionate vagus: A meta-analysis on the connection between compassion and heart rate variability. Neurosci. Biobehavioral Reviews. 116, 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.06.016 (2020).

Sherwell, C. S. & Kirby, J. N. Compassion focused therapy and heart rate variability. In: Integrating Psychotherapy and Psychophysiology. Edited by: Patrick R. Steffen and Donald Moss. Oxfordshire, UK; Oxford University Press, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198888727.003.0018

Matos, M. & Steindl, S. R. You are already all you need to be: A case illustration of compassion-focused therapy for shame and perfectionism. J. Clin. Psychol. 76 (11), 2079–2096. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23055 (2020).

Matos, M., Petrocchi, N., Irons, C. & Steindl, S. R. Never underestimate fears, blocks, and resistances: the interplay between experiential practices, self-conscious emotions, and the therapeutic relationship in compassion focused therapy. J. Clin. Psychol. 79 (7), 1670–1685. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23474 (2022).

Sousa, R., Petrocchi, N., Gilbert, P. & Rijo, D. Unveiling the heart of young offenders: testing the tripartite model of affect regulation in community and forensic male adolescents. J. Criminal Justice. 82 (1), 101970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2022.101970 (2022).

Gilbert, P. et al. An exploration of different types of positive affect in students and patients with bipolar disorders. Clin. Neuropsychiatry: J. Treat. Evaluation. 6 (4), 135–143 (2009).

Matos, M., Duarte, J., Duarte, C., Gilbert, P. & Pinto-Gouveia, J. How one experiences and embodies compassionate Mind training influences its effectiveness. Mindfulness 9 (4), 1224–1235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0864-1 (2017).

Kirschner, H. et al. Soothing your heart and feeling connected: A new experimental paradigm to study the benefits of self-compassion. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 7 (3), 545–565. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702618812438 (2019).

Watson, D., Clark, L. & Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 54 (6), 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063 (1988).

Sommers-Spijkerman, M. P., Trompetter, H. R., Schreurs, K. M. & Bohlmeijer, E. T. Compassion-focused therapy as guided self-help for enhancing public mental health: A randomized controlled trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 86 (2), 101–115. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000268 (2018).

Cowles, M., Randle-Phillips, C. & Medley, A. Compassion-focused therapy for trauma in people with intellectual disabilities: A conceptual review. J. Intellect. Disabil. 24 (2), 212–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629518773843 (2020).

Petrocchi, N., Kirby, J. & Baldi, B. Essentials of Compassion Focused Therapy: A Practice Manual for Clinicians (UK; Routledge, 2024). Oxfordshire.

Kirby, J. N., Sherwell, C., Lynn, S. & Moloney-Gibb, D. Compassion as a framework for creating individual and group-level wellbeing in the classroom: new directions. J. Psychologists Counsellors Schools. 33 (1), 2–12. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2023.5 (2023).

Lesage, F. X., Berjot, S. & Deschamps, F. Clinical stress assessment using a visual analogue scale. Occup. Med. 62 (8), 600–605. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqs140 (2012).

Pincus, T. et al. Visual analog scales in formats other than a 10 centimeter horizontal line to assess pain and other clinical data. J. Rhuematol. 35 (8), 1550–1558 (2008).

Jenkins, B. N. et al. The subcomponents of affect scale (SAS): validating a widely used affect scale. Psychol. Health. 38 (8), 1032–1055. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2021.2000612 (2021).

Lovibond, P. F. & Lovibond, S. H. The structure of negative emotional States: comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the Beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 33 (3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u (1995).

Victor, S. E. & Klonsky, E. D. Validation of a brief version of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale (DERS-18) in five samples. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 38 (4), 582–589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-016-9547-9 (2016).

Fleiss, J. L. The Design and Analysis of Clinical Experiments (Wiley, 1986).

Gilbert, P. et al. Feeling safe and content: A specific affect regulation system? Relationship to depression, anxiety, stress, and self-criticism. J. Posit. Psychol. 3 (3), 182–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760801999461 (2008).

Kirby, J. N. (ed Gilbert, P.) Commentary regarding Wilson et al. (2018) effectiveness of ‘self-compassion’ related therapies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. All is not as it seems. Mindfulness 10 1006–1016 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-1088-8 (2019).

Pekrun, R. The control-value theory of achievement emotions: assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educational Psychol. Rev. 18, 315–341 (2006).

Walton, C. C. et al. Self-compassionate motivation and athlete well-being: the critical role of distress tolerance. J. Clin. Sport Psychol. 18 (1), 131–149. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.2022-0009 (2022).

Moroz, N., Moroz, I. & D’Angelo, M. S. Mental health services in Canada: barriers and cost-effective solutions to increase access. Healthc. Manage. Forum. 33 (6), 282–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/0840470420933911 (2020).

World Health Organization (WHO) World mental health report: Transforming mental health for all. Geneva, Spain; World Health Organization. ISBN: 978-92-4-004933-8. (2022).

Lattie, E. G., Stiles-Shields, C. & Graham, A. K. An overview of and recommendations for more accessible digital mental health services. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 1, 87–100. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-021-00003-1 (2022).

Muñoz, R. F. Harnessing psychology and technology to contribute to making health care a universal human right. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 29 (1), 4–14 (2022).

Sherwell, C. S. et al. Examining the impact of a brief compassion focused intervention on everyday experiences of compassion in autistic adults through psychophysiology and experience sampling. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-024-09681-y

Worthington, R. L. & Whittaker, T. A. Scale development research. Couns. Psychol. 34 (6), 806–838. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006288127 (2006).

Venkatesh, H., Osorno, A. M., Boehm, J. K. & Jenkins, B. N. Resilience factors during the coronavirus pandemic: testing the main effect and stress buffering models of optimism and positive affect with mental and physical health. J. Health Psychol. 28 (5), 405–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591053221120340 (2022).

Antony, M. M., Bieling, P. J., Cox, B. J., Enns, M. W. & Swinson, R. P. Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the depression anxiety stress scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychol. Assess. 10 (2), 176–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.10.2.176 (1998).

Lovibond, S. H. & Lovibond, P. F. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (Psychology Foundation of Australia, 1996).

Norton, P. J. Depression anxiety and stress scales (DASS-21): psychometric analysis across four Racial groups. Anxiety Stress Coping. 20 (3), 253–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800701309279 (2007).

Gratz, K. L. & Roemer, L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 26 (1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:joba.0000007455.08539.94 (2004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.M.G., C.S., S.L., J.D., and J.N.K. all designed the study and conceptualisation; D.M.G. completed data collection; D.M.G. and C.S. performed data analyses; D.M.G., C.S., J.D., S.L., and J.N.K. all drafted the manuscript and contributed. All authors approved the final version of the paper for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by the University of Queensland’s Institutional Human Research Ethics Committee (HE000177) and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all participants provided written informed consent.

Accession codes

The dataset generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available on the Open Science Framework at the following link: https://osf.io/b8zdv. Custom computer code was not utilised to generate results; standard Jamovi functions were utilised, and thus custom code is not available. All psychometrics used were unaltered from original scales, aside from the specified time period alterations to accommodate the “today” and “over the past week” time periods. The video shown to participants is available at https://youtu.be/CUBloap2ixI. A demo of the Three Circles app is available at https://threecircles.app/demo.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moloney-Gibb, D., Sherwell, C.S., Lynn, S. et al. Testing a digital and interactive scale (the three circles) to assess emotion regulation. Sci Rep 15, 16351 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94706-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94706-7