Abstract

Among the many methods and techniques for optimizing the soil-cultivating unit parameters, the method of Lagrange multipliers occupies a special place. In this article, the Lagrange method is used to develop analytical dependencies that make it possible to determine the optimal values of the operating width and operating speed of tillage (ploughing and cultivating) units at a set value of tractor engine power and the linear nature of the dependence of its slipping on traction force. As a result, it was found that the decreasing intensity in the ploughing unit operating width (\(\:B\)) with an increase in the plough’s specific resistance coefficient (\(\:{K}_{s}\)) is practically independent of the ploughing depth (\(\:h\)). When changing the value of this parameter in the range of 0.22–0.30 m, increasing the value of the \(\:{K}_{s}\) coefficient from 50 to 65 kN m− 2 requires reducing the value of parameter \(\:B\) by 23%. The maximum performance of the tractor with the plough occurs at the minimum possible values of the \(\:{K}_{s}\), \(\:h\) and \(\:V\) parameters. This result is achieved by increasing the ploughing unit operating width. At the same time, the maximum performance of the tractor with the cultivator is achieved at the maximum possible values of the \(\:{K}_{s}\) (3.6 kN m− 1) and \(\:V\) (3.0 m s− 1) parameters and amounts to 8.6 ha h− 1. Compared to the option for the minimum values of the \(\:{K}_{s}\) (3.0 kN m− 1) and \(\:V\) (2.0 m s− 1) parameters, this is 28.4% more.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Machine-tractor units (MTU) are the technical base for the practical implementation of agricultural cultivation technology. Among their characteristics, one of the most important is performance (\(\:W\)). Essentially, this indicator is a function of such MTU parameters as its operating width (\(\:B\)) and the operating movement velocity (\(\:V\)), that is, \(\:W=f(B;V)\).

It should be noted that this function does not have an optimum. Moreover, there is an opposite relationship between \(\:B\) and \(\:V\) parameters. Its essence is that with the same power load of the tractor engine, an increase in the unit movement velocity is possible with a certain reduction in its operating width and vice versa. All this creates difficulties in determining such values of \(\:B\) and \(\:V\) parameters that ensure the fulfilment of the condition \(\:W=f(B;V)\to\:\text{m}\text{a}\text{x}\). The machine-tractor unit performance decreases with non-optimal values of the V and B parameters. And this causes the following negative consequences. First of all, this is due to the specific fuel consumption (\(\:{G}_{s}\), kg h−1), which is determined from the equation: \(\:{G}_{s}={G}_{t}/W\), where \(\:{G}_{t}\) is the MTU fuel consumption for 1 h of its operation, kg h− 1. From this, we see that the lower the W value, the undesirable greater the \(\:{G}_{s}\) indicator value is. Secondly, with a small value of W, the duration of agricultural technological operations increases. When sowing agricultural crops, this is associated with a decrease in their yield. Thirdly, low MTU productivity due to the incorrect choice of the V and B parameters values leads to an undesirable increase in operating costs.

To the above, we add that the unit’s movement velocity and operating width determine the required tractor engine power (\(\:{N}_{e}\)). But the function \(\:{N}_{e}=f\left(B;V\right)\) also does not have an extremum, while the value of the parameter \(\:{N}_{e}\) is always limited. As a result, the task arises of increasing the machine-tractor unit performance (\(\:W\)) with limited values of both the tractor engine power (\(\:{N}_{e}\)) and the \(\:B\) and \(\:V\) parameters. In other words, it is necessary to search for the conditional optimum of the function \(\:W\) under certain restrictions.

At the moment, many solutions to such problems have been developed. For example, the study1 used statistical models to predict the probability of the cultivators working parts’ failure-free operation. Their operating time (in hours) and power load coefficients were selected as optimization criteria.

The Pontryagin minimization principle was used to optimize the fuel energy consumption of a tractor as part of a ploughing unit2. In this case, the control variable was the engine power, which determines the MTU performance. Applying this optimization method provided no less than 9% fuel energy savings for ploughing MTU.

Optimization of the sowing unit parameters was carried out by3. The following optimization criteria were adopted: (1) energy costs, taking into account the expected losses of agricultural crop yield; (2) minimum CO2 emissions into the atmosphere; (3) minimum fuel consumption by the unit per 1 ha; (4) maximum performance of the seeding MTU; (5) maximum traction efficiency of the tractor. In the research process, the weight of the tractor, the unit’s operating speed, the seeder’s working width and its coefficient of specific resistance were optimized. A similar optimization problem was solved concerning a ploughing unit4.

Many studies are devoted to optimizing the parameters of soil-cultivating units using the theory of planning a full factorial experiment. In this case, machines with passive5 and active working parts6 were considered. The optimization criteria were the specified soil density level and the tillage machine’s minimum traction resistance.

In addition to statistical, simulation and other models, economic and statistical models are used to optimize the parameters of tillage units7. The optimization parameter is the operating performance (\(\:W\)) of these MTUs. However, the increase in parameter W is carried out by improving the organization of sowing crops. For this, the authors use a particular coefficient that reflects the degree to which the unit uses its working time.

In the study8, the minimum energy cost was the target function for optimizing the unit’s parameters for sowing row crops. Notably, the optimal values of the unit’s operating width and operating speed are selected classically ‒ using the tractor’s traction characteristics.

Rarely used in soil cultivation, but a rather complex method of smoothed particle hydrodynamics (known as the SPH method) was used to optimize the parameters of a unit operating in a semi-fluid soil environment9. Studies devoted to the parameters optimization of dynamic systems using a particle swarm are of particular interest10. A rather original problem of minimizing/maximizing the costs of opportunistic maintenance of a dynamic system to optimize its operational reliability is solved in11.

Recently, attempts have been made to optimize the parameters of tillage units using the theory of artificial neural networks12,13. Despite some effectiveness, this method has a significant drawback. Like the method of planning a full factorial experiment, it is based on the principles of a “black box”. This approach to solving the problem does not allow us to reveal its internal nature due to the lack of an appropriate mathematical description.

One example of the classic use of developed theoretical dependencies to optimize the parameters of a ploughing unit is the research conducted by14. In this work, the author solved the issue of increasing the MTU performance by using the world-famous formula for plough traction resistance developed by V.P. Goryachkin. As a result of research, it has been established that an increase in the \(\:W\) parameter at constant engine power (\(\:{N}_{e}\)) is advisable due to an increase not in the ploughing unit movement velocity (\(\:V\)) but in its operating width (\(\:B\)).

The above-listed scientific works have the following main shortcomings. First, almost all of them do not allow for effective solutions to optimization problems that require direct connection with several constraints (especially nonlinear ones) in the form of equalities. This is important, especially when separate considerations of such constraints do not solve the problem. Secondly, the optimization methods listed above are not flexible enough to solve minimization and maximization problems. Thirdly, many optimization methods do not have a clear enough mathematical basis that allows one to obtain a solution using the first partial derivative, which is the basis for proving the existence of an optimum.

It should be noted that the Lagrange multiplier method is free from almost all of these shortcomings in optimizing the parameters of soil-cultivating units15,16,17. It can be applied to a wide range of optimization problems, including problems with equalities and/or inequalities in constraints. Lagrange multipliers help transform an optimization problem’s conditions into constraints, simplifying finding an extremum. Since this method leads to solving equations consisting of equations for partial derivatives concerning variables and equations for Lagrange multipliers, it is simpler than working with the original system of conditions. Moreover, the Lagrange multiplier method works well for problems that may be irregular. They have discontinuous gradients or other features that can cause difficulties for other optimization methods. Finally, this method considers several constraints, making it suitable for solving complex problems with multiple conditions.

An example of a relatively effective application of the Lagrange method is studies devoted to solving the problem of optimizing tractor transmission parameters18,19,20,21. However, the techniques used in these works are not suitable for solving the problem of optimizing the design parameters of a soil-cultivating unit in general and a ploughing unit in particular.

In the work22, the Lagrange method was used to determine the optimal values of the sowing unit movement velocity and operating width at a constant value of the tractor engine power. The disadvantages of the results presented in this article include the following. Firstly, the analytical dependencies do not allow the optimal values of the \(\:V\) and \(\:B\) parameters for a ploughing unit to be chosen. Secondly, the process of tractor slipping is described by a nonlinear relationship. And this, in our opinion23, is an inadequate result. Thirdly, the article’s materials are limited only to analytical dependencies. There is absolutely no practical use of them. This does not allow us to evaluate the obtained patterns quantitatively or even qualitatively within the Lagrange method framework.

In connection with the above, this article aims to use the Lagrange method to develop analytical dependencies that make it possible to determine the optimal values of the tilling units operating width and operating velocity at a set value of tractor engine power and the linear nature of the dependence of its slipping on traction force. This formulation of the problem is new. First of all, it concerns the adoption of a limitation in the form of a linear dependence of the tractor wheels slippage on the traction force developed by it. Such a limitation is directly related to the established level of the tractor engine power. The developed method for determining the optimal parameters of soil-cultivating units will fill the gap that was admitted in previous studies related to the use of the Lagrange method.

Theoretical premises

The ploughs’ specific resistance coefficient is measured in kN m− 2 for ploughing units. For other soil-cultivating machine-tractor units, the value of the specific resistance coefficient of their working devices has the dimension kN m− 1. Considering this, we take two machine-tractor units as objects of research: (1) ploughing and (2) unit for continuous soil cultivation.

First of all, let’s look at the ploughing unit. The Lagrange function (\(\:F\)) for our problem looks like this

where \(\:\lambda\:\) ‒ Lagrange multiplier.

The performance of a ploughing MTU can be defined as follows:

The coefficient 0.36 in formula (2) indicates that the plough operating width (\(\:B\)) is in m, and the ploughing unit’s movement velocity (\(\:V\)) is in m s− 1.

The tractor engine power value is determined from the well-known equation:

here \(\:{K}_{s}\) ‒ plough’s specific resistance coefficient (kN m− 2); \(\:h\) ‒ ploughing depth (m); \(\:f\) ‒ rolling resistance coefficient; \(\:G\) ‒ tractor’s operating weight (kN); \(\:{\eta\:}_{t}\) ‒ tractor transmission efficiency; \(\:\delta\:\) ‒ tractor’s slipping.

Our research has established23,24 that the maximum permissible tractor slip should not exceed 15%. The dependence of this indicator on traction force is linear:

where \(\:a,\:b\) ‒ approximation coefficients.

Taking into account dependence (4), Eq. (3) takes the form:

A necessary condition for the existence of the Lagrange function extreme value is the equality to zero of its partial derivatives concerning the controlled parameters (that is, \(\:B\) and \(\:V\)):

From the system of Eq. (6), it follows that the problem consists of solving the next two equations:

Having eliminated the Lagrange multiplier λ from the system of Eq. (7), we obtain the following:

Further research is to find the partial derivatives included in Eq. (8). They look like this:

In Eqs. (9)-(12) the following notations are used:

Substituting partial derivatives from (9)-(12) into (8), after transformations we finally obtain:

where

Cubic Eq. (13) is an analytical relationship that allows you to determine the optimal value of the plough operating width (\(\:B\)). Next, given the ploughing unit’s movement velocity value (\(\:V\)), from Eq. (5), you can determine the required value of the tractor engine power (\(\:{N}_{e}\)). The resulting values of the \(\:B\), \(\:V,\) and \(\:{N}_{e}\) parameters will ensure that the ploughing unit obtains maximum performance (\(\:W\)).

It should be noted that if, for a plough, the coefficient of specific traction resistance \(\:{K}_{s}\) has the dimension kN m− 2, then for other tillage machines it is measured in kN m− 1. In this case, the equation for determining the tractor engine power will be different:

Following this, the coefficients of Eq. (13) will also be different:

Otherwise, the algorithm for determining the \(\:B\), \(\:V,\) and \(\:{N}_{e}\) parameters are the same as for the ploughing unit.

Materials and methods

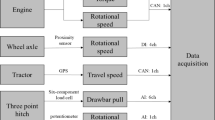

Experimental units

Two machine-tractor units were taken as physical research objects: ploughing and cultivating. The first consists of the KhTZ-17,021 tractor (Ukraine) and the five-furrow-mounted plough PLN-5-35 (Fig. 1).

The cultivator unit consisted of the same tractor and the KRN-8.4 cultivator, designed for soil cultivation to a depth of 0.08–0.12 m (Fig. 2).

Brief technical characteristics of both units are given in Table 1.

Test conditions

To theoretically analyze dependence (13), you need to know the values of its parameters. This applies to the tractor slip approximation coefficients \(\:a\) and \(\:b\), as well as the specific resistance coefficients of the plough and cultivator (\(\:{K}_{s}\)).

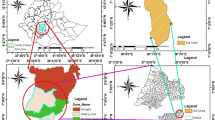

Experimental determination of these parameters values was carried out in the conditions of the south of Ukraine (46◦50′56″ north latitude, 35◦21′55″ east longitude, altitude: 37 m). The ploughing unit was studied in the summer on the stubble of winter wheat, and the cultivator unit ‒ the following spring on the background processing ploughed in the fall. Before conducting the research, soil density and moisture were determined. For a ploughing unit, these parameters were determined in a layer of 0–30 cm and for a cultivator MTU ‒ in a layer of 0–12 cm. Instruments and methods of their use for determining soil density and moisture are described in detail in the article25.

Methodology for determining approximation coefficients a and B

To find the approximation coefficients a and b, the ploughing unit was used (Fig. 1). It is convenient to present Eq. (4) in the following form:

where \(\:{P}_{d}\) ‒ plough’s traction resistance (kN); \(\:\phi\:\) ‒ tractor’s net traction coefficient.

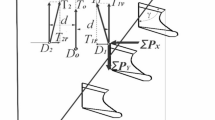

During field tests, the traction resistance of the plough (\(\:{P}_{d}\)) was changed by varying the ploughing depth from 0.14 to 0.30 m with an interval of 0.04 m. This parameter was measured with a unique device (Fig. 3). The method of its use is described in the article26.

The plough operating width after each pass of the ploughing unit was determined as follows. Fifty pegs were installed perpendicular to the furrow wall of the previous MTU pass at a distance \(\:L\) with a step of 1 m (Fig. 4). After passing the ploughing unit using a Dnipro-M Multi Fix (Ukraine) tape measure, the \(\:{h}_{i}\) distance from each peg to the newly formed furrow was measured with an error of ± 0.5 cm.

As a result, the mean value of the MTU operating width was calculated using the formula:

The plough had a unique movable frame to measure its traction resistance. A sensor with four foil strain gauge resistors with a nominal value of 200 Ohms each, assembled into a measuring bridge, was installed on this frame (Fig. 5). In each experiment, the electrical signal from the sensor was fed to one of the analogue inputs of the Arduino Uno (Italy) for at least 60 s. It was recorded onto a microCD with an interval of 0.1 s using an HW-125 (Chine) adapter.

The data obtained this way was used to calculate the mean value of the plough traction resistance (\(\:{P}_{d}\)). By dividing the resulting \(\:{P}_{d}\) value by the tractor’s operating weight (\(\:G\)), the required value of the tractor’s net traction coefficient (\(\:\phi\:\)) was obtained. The parameter \(\:G\) value was determined by weighing the KhTZ-17,021 tractor five times on an OKS-10t-XZC2 (Ukraine) crane scale with a measurement error of ± 5 kg.

Tractor wheel slip was calculated using the formula27:

where \(\:{n}_{x},{V}_{x}\) ‒ wheels revolutions (s− 1) and moving velocity (m s− 1) of the tractor without net traction;\(\:\:{n}_{p},{V}_{p}\) – revolutions of the tractor wheels and the velocity of its movement under net traction.

They were equipped with special devices to determine the tractor wheels’ revolutions. Each device had 2 Y213 (Chine) normally open sealed contacts and 2 magnets (Fig. 6).

The response time of these hermetic contacts is 0.45 ms. Electrical signals from the hermetic contacts were sent to another analogue input of the Arduino Uno. After appropriate digital processing, they were recorded on microSD as wheel velocity values.

During the field research, the ploughing unit movement velocity was measured simultaneously by recording the plough’s traction resistance and the tractor wheels’ revolutions on Arduino Uno. To carry out these measurements, a field with winter wheat stubble was divided into sites, each 250 m long. On the first 25 m, the MTU was accelerated. Over the next 200 m, the \(\:{P}_{d}\) and \(\:{n}_{p}\left({n}_{x}\right)\) parameters were recorded. At the same time, the time (\(\:t\), s) for the unit to pass the test site was recorded. For this purpose, we used an XL-009 (Chine) electronic stopwatch with a measurement accuracy of 0.01 s. The unit movement velocity (m s− 1) was calculated using the formula \(\:{V}_{p}\left({V}_{x}\right)=200/t\).

After MTU was stopped, the ploughing depth (h) and the plough operating width (B) were measured. The method for determining these parameters is described above. All described measurements were carried out in two replicates.

After calculating the tractor’s net traction and slipping coefficient values, a graphical dependence \(\:\delta\:=f\left(\phi\:\right)\:\)was built in Microsoft Excel. As a result of approximating it with a straight line, the values of the \(\:a\) and \(\:b\) coefficients were obtained, which were subsequently used for theoretical studies. The confidence interval for the dependence \(\:\delta\:=f\left(\phi\:\right)\:\)was calculated with a confidence probability of 95% using the Data Analysis Toolpak in Excel package.

Methodology for determining the values of the coefficient \(\:{K}_{s}\)

The plough resistivity coefficient (kN m− 2) was calculated using the formula:

The values of ploughing depth (\(\:h\)) and the PLN-5-35 plough operating width (\(\:B\)), as well as its resulting traction resistance (\(\:{P}_{d}\)), were determined according to the method described above. The values of the coefficient \(\:{K}_{s}\) obtained as a result of calculations were used for theoretical studies of the Eq. (13).

To calculate the specific resistance coefficient (kN m− 1) of the KRN-8.4 cultivator (Fig. 2), we used the following equation:

The traction resistance of this machine was determined using the same strain sensor (Fig. 5) used in the study of the ploughing unit.

The depth of tillage with the KRN-8.4 cultivator carried out in the spring on the field after ploughing the winter wheat stubble was kept approximately constant at 0.10 m. The cultivator unit movement velocity was at the level recommended for use in the conditions of southern Ukraine ‒ 2.3–2.5 m s− 1.

The operating width of the KRN-8.4 cultivator was measured according to the method described in the previous section. The determination of this parameter (as well as traction resistance) was repeated five times.

Results and discussion

Ploughing machine-tractor unit

The ploughing unit was researched on a field whose humidity in the 0–30 cm layer was 15.8%, and the bulk density was 1.29 g cm− 3. The results of field studies show (Table 2) that when the ploughing depth changed within 0.14–0.30 m, the mean value of the PLN-5-35 plough traction resistance was changed from 14.7 to 32.8 kN.

The wheel slip of the KhTZ-17,021 tractor did not exceed 15%. As a result, the tractor’s net traction coefficient took values from 0.18 to 0.40. Presentation of the dependence \(\:\delta\:=f\left(\phi\:\right)\) in graphical form showed that it is satisfactorily approximated with a straight line \(\:\delta\:=0.04+0.27\cdot\:\phi\:\) (Fig. 7).

Two facts evidence this. The first is a reasonably high value of the determination coefficient (\(\:{R}^{2}=0.987\)). The second evidentiary fact is that the outspread of tractor slip values relative to the direct approximation does not exceed the boundaries of the confidence range constructed for a statistical significance level of 0.05. From the equation of the linear dependence of the tractor slipping on its net traction coefficient, the approximation coefficient values are equal: \(\:a\) = 0.04 and \(\:b\) = 0.27.

The plough’s specific resistance coefficient values were determined using the data in Table 2 and formula (16). Calculations established that the parameter \(\:{K}_{s}\) value varied from 58.6 to 61.7 kN m− 2 (Table 2). A similar range of changes in this parameter (46–66 kN m− 2) was obtained in studies4.

To conduct theoretical studies, we have adopted the following range of parameter changes ‒ \(\:{K}_{s}\) = 50–65 kN m−2. Calculations show that the greater the value of this parameter, the smaller the plough design operating width should be (Fig. 8).

on the value of its specific resistance coefficient.

In this case, the following regularity takes place: the intensity of this process (that is, a decrease in \(\:B\) parameter with an increase in \(\:{K}_{s}\) parameter) does not depend on the ploughing depth. For any value of ploughing depth considered in the study from 0.22 to 0.30 m, an increase in the plough’s specific traction resistance from 50 to 65 kN m− 2 requires a reduction in the plough operating width by 23%.

Almost the same pattern appears in another process. It is associated with a change in the plough operating width when the ploughing depth changes. As follows from the analysis of the calculated data, an increase in the value of \(\:h\) parameter from 0.22 to 0.30 m causes a decrease in the value of \(\:B\) parameter by 26.6% (Fig. 9). And this level practically does not depend on the value of the plough specific traction resistance coefficient, which varies in the range of 50–65 kN m− 2.

Taking into account the variability of the \(\:{K}_{s}\), \(\:h\) and \(\:V\) values, we will consider three options for their combinations: option A ‒ the minimum values of these parameters; option B ‒ mean values; option C ‒ maximum values. Next, for each of these options, using formulas (2), (4), (5) and (13), we calculate the plough operating width (\(\:B\)), the tractor engine power (\(\:{N}_{e}\)) and the slipping of its wheels (\(\:\delta\:\)), the productivity of the ploughing unit (\(\:W\)).

Analysis of the results obtained shows that with minimum values of the \(\:{K}_{s}\), \(\:h\) and \(\:V\) parameters, the ploughing unit consisting of the KhTZ-17,021 tractor and PLN-5-35 plough has a maximum performance equal to 1.75 ha h− 1 (Table 3, option A). However, it was achieved not by increasing the movement velocity but by increasing the plough operating width to 2.43 m. This trend entirely coincides with what is outlined in the article28,29,30.

The minimum operating performance of this MTU, equal to 1.48 ha h− 1 (Table 3, option C), was obtained with maximum values of the \(\:{K}_{s}\), \(\:h\) and \(\:V\) parameters. In this case, the required tractor engine power is 1.5 times greater than in option A. This is important since the maximum values of the \(\:{K}_{s}\), \(\:h\) and \(\:V\) parameters are more realistic in practice than the minimum or even mean values (option B, Table 3).

Cultivating machine-tractor unit

MTU studies as part of the KhTZ-17,021 tractor and the KRN-8.4 cultivator (Fig. 2) were carried out on a field ploughed in the fall harrowed before cultivation. The mean soil moisture in the 0–10 cm layer was 20.4%, and the bulk density was 1.12 g cm− 3. The field cultivation depth varied within 11.1 ± 0.3 cm. The cultivator operating width was 8.5 ± 0.1 m. At the unit moving velocity at 2.4 m s− 1, the mean value of the cultivator traction resistance was 27.2 kN. As a result, it was found that the specific resistance coefficient KRN-8.4 \(\:{K}_{s}\) = 3.2 kN m−1. In similar studies3, the value of this coefficient was obtained at a level of 4 kN m− 1. Considering this, in theoretical studies, the \(\:{K}_{s}\) parameter was varied within the range of 3.0-3.6 kN m− 1.

We used Eq. (13) for theoretical calculations with coefficient values in which the dimension of the machine’s specific traction is presented as kN m− 1. The rolling resistance coefficient (\(\:f\)) value was taken constant and equalled 0.14. According to our data, this parameter’s particular value is typical in southern Ukraine during spring soil cultivation, with a humidity of 18–22% and density not exceeding 1.25 g cm− 3.

As for the parameter \(\:G\) and the \(\:a\) and \(\:b\) approximation coefficients, their values were the same as in the calculations of the ploughing unit.

From the analysis of the calculated data, it follows that an increase in the value of the cultivator resistance coefficient from 3.0 to 3.6 kN m− 1 causes a decrease in its operating width from 9.6 to 8.0 m, that is, by 16.7% (Fig. 10). In principle, the function \(\:B=f\left({K}_{s}\right)\) is nonlinear. However, for the accepted values of the cultivator resistivity coefficient (3.0-3.6 kN m−1), its linear interpretation is quite suitable.

As in the plough case, we will consider three possible combinations of \(\:{K}_{s}\) and \(\:V\) parameter values (Table 4).

Analysis of the data obtained shows that, in contrast to the ploughing unit, the highest performance of the KhTZ-17,021 tractor with the KRN-8.4 cultivator (8.6 ha h− 1) occurs at the maximum values of the \(\:{K}_{s}\) and \(\:V\) parameters (option C, Table 4). Compared to option A, the increase in W parameter is 28.4%. Moreover, it was achieved by increasing not the unit operating width but the operating velocity of its movement. In this case, an increase in the value of \(\:V\) parameter by 50% (from 2 to 3 m s− 1) covered the decrease in the cultivator operating width (from 9.6 to 8.0 m) by 16.7%.

Conclusions

Based on the use of Lagrange multipliers and the linear nature of the dependence of the tractor slipping on the traction force it develops, equations have been developed that make it possible to determine the optimal values of the machine operating width for ploughing and moldless tillage. Having specified the soil-cultivating units’ movement velocity (\(\:V\)), these equations make it possible to calculate the tractor engine power that ensures maximum performance of the MTUs.

The decreased intensity in the ploughing unit operating width (\(\:B\)) with an increase in the plough specific coefficient resistance (\(\:{K}_{s}\)) is practically independent of the ploughing depth (\(\:h\)). When changing the value of this parameter in the range of 0.22–0.30 m, increasing the \(\:{K}_{s}\) coefficient value from 50 to 65 kN m− 2 requires reducing the value of parameter \(\:B\) by 23%.

The maximum performance of the tractor with the plough occurs at the minimum possible values of the \(\:{K}_{s}\), \(\:h\) and \(\:V\) parameters. This result is achieved by increasing the ploughing unit operating width. At the same time, the maximum performance of the tractor with the cultivator is achieved at the maximum possible values of the \(\:{K}_{s}\) and \(\:V\) parameters and is equal to 8.6 ha h− 1. Compared to the option for the minimum values of the \(\:{K}_{s}\) and \(\:V\) parameters, this is 28.4% more.

A further research direction is using neural networks to implement a machine learning algorithm for a tillage unit to make a decision to maximize its performance. The initial parameters in this case can be soil moisture and soil bulk density, the depth of its processing, the dynamics of changes in the tillage machine specific resistance coefficient, etc.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Alfyorov, O. et al. Agricultural equipment design optimization based on the inversion method. Agric 12, 1410. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12091410 (2022).

Feng, G. et al. Research on energy-saving control of agricultural hybrid tractors integrating working condition prediction. PLoS One. 19, e0299658. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0299658 (2024).

Khafizov, C. A., Khafizov, R. N., Nurmiev, A. A. & Gayaziev, I. N. Selection of the main parameters of tractors for direct sowing of grain crops according to various optimization criteria. BIO Web Conf. 52, 00045. https://doi.org/10.1051/bioconf/20225200045 (2022).

Khafizov, C., Khafizov, R., Nurmiev, A. & Galiev, I. Optimization of main parameters of tractor and unit for plowing soil, taking into account their influence on yield of grain crops. Eng. Rural Dev. 19, 585–590. https://doi.org/10.22616/ERDev.2020.19.TF131 (2020).

Sharonov, I., Kurdyumov, V., Isaev, Y. & Kurushin, V. The optimization of the cylinder-spiral soil-cultivating roller. E3S Web Conf. 193, 01001. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202019301001 (2020).

Niyomuvunyi, A. et al. Optimisation of parameters and operating modes of the unit for preparing soil for planting rice in Burundi. E3S Web Conf. 486, 06004. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202448606004 (2024).

Shepelev, S., Shepelev, V. & Almetova, Z. Optimization of technical equipment for crop sowing processes. Procedia Eng. 150, 1258–1262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2016.07.142 (2016).

Tsybulevsky, V. V., Maslov, G. G. & Ushakov, D. A. Optimization of machine-tractor parameters units for target functions with minimum costs total energy. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 839, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/839/5/052028 (2021).

Zhongzhi, L. Research, analysis and optimization of the drive characteristics of the drive wheel of the machine tiller based on SPH method. Appl. Math. Nonlinear Sci. 9, 3383–3392. https://doi.org/10.2478/amns.2023.2.00537 (2024).

Shi, J. et al. The optimization design for the journal-thrust couple bearing surface texture based on particle swarm algorithm. Tribol. Int. 198, 109874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2024.109874 (2024).

Lu, Y. et al. Adaptive maintenance window-based opportunistic maintenance optimization considering operational reliability and cost. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 250, 110292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2024.110292 (2024).

Nagar, H., Machavaram, R., Kulkarni, P. & Soni, P. AI-based engine performance prediction cum advisory system to maximize fuel efficiency and field performance of the tractor for optimum tillage. Syst. Sci. Control Eng. 12, 2347936. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642583.2024.2347936 (2024).

Saleh, B. & Aly, A. A. Artificial neural network model for evaluation of the ploughing process performance. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 2, 1–11 (2013).

Valge, A. M. Optimization of soil tilling unit parameters. AgroEcoEngineering 1, 49–55. https://doi.org/10.24411/0131-5226-2020-10226 (2020).

Nadykto, V. et al. Research on a machine–tractor unit for strip-till technology. AgriEngineering. 5, 2184–2195. (2023).

Lasdon, L. S. Optimisation Theory for Large Systems (Courier Corporation, 2002).

Sabach, S. & Teboulle, M. Lagrangian methods for composite optimization. Handb. Numer. Anal. 20, 401–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.hna.2019.04.002 (2019).

Hu, Y. & Liang, H. Folding simulation of rigid origami with Lagrange multiplier method. Int. J. Solids Struct. 202, 552–561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2020.06.016 (2020).

Senkevich, S. et al. Elastic damping mechanism optimisation by indefinite lagrange multipliers. IEEE Access. 9, 71784–71804. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3078609 (2021).

Wu, S., Yan, H. Z., Bi, R., Wang, Z. & Zhu, P. Nonlinear optimization method for transmission error of hypoid gear machined by the duplex helical method. Math. Probl. Eng. 9626089. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/9626089 (2020).

Zhang, H., Zhao, X. & Sun, J. Optimal clutch pressure control in shifting process of automatic transmission for heavy-duty mining trucks. Math. Probl. Eng. 8618759. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8618759 (2020).

Konstantinov, M. M., Nuralin, B. N., Fedorov, A. N. & Kuramshin, M. R. Optimization of operational parameters of the seeding unit. News Orenbg State Agrar. Univ. 2, 68–71 (2005). (in Russian).

Nadykto, V., Arak, M. & Olt, J. Theoretical research into the frictional slipping of wheel-type undercarriage taking into account the limitation of their impact on the soil. Agron. Res. 13, 148–157 (2015).

Nadykto, V. et al. Determination of operation performance indicators of unit for mowing crops with the simultaneous incorporation of their stubble into the soil. Sci. Rep. 14, 15373. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66183-x (2024).

Adamchuk, V., Bulgakov, V., Nadykto, V. & Ivanovs, S. Investigation of tillage depth of black fallow impact upon moisture evaporation intensity. Eng. Rural Dev. 19, 377–383. https://doi.org/10.22616/ERDev.2020.19.TF090 (2020).

Findura, P., Nadykto, V., Kyurchev, V. & Gierz, Ł. Transverse movement kinetics of a unit for inter-row crops - case study: cultivator unit. Appl. Sci. 14, 580. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14020580 (2024).

Bulgakov, V., Nadykto, V., Ivanovs, S. & Dukulis, I. Improving the performance of a ploughing tractor by means of an auxiliary carriage with motorized axle. J. Agric. Eng. 52, 9–16. https://doi.org/10.4081/jae.2021.1109 (2021).

Boryga, M. Trajectory planning for tractor turning using the trigonometric transition curve. Agricultural Eng. 27(1), 203–212. https://doi.org/10.2478/agriceng-2023-0015 (2023).

Nadykto, V. & Kuyrchev, V. Prospects for increasing the performance of a machine-tractor unit. Tech. Technol. Agro-Industrial Complex. 7, 26–31 (2018). (in Ukraine).

Adekunle, A. & Oseni, O. Development and performance evaluation of a small scale kenaf fibre spinning and reeling machine. Agricultural Eng. 27(1), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.2478/agriceng-2023-0012 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Anonymous reviewers are gratefully acknowledged for their constructive review that significantly improved this manuscript, International Visegrad Fund (http://www.visegradfund.org) and Ukrainian University in Europe (https://universityuue.com).

Funding

This project has received funding from the Ministry of Education of Science Republic Poland for the Agricultural University in Krakow for the year 2025 and Ministry of Education, Science and Sports of the Republic of Lithuania and Research Council of Lithuania (LMTLT) under the Program’ University Excellence Initiative’ Project ‘Development of the Bioeconomy Research Center of Excellence’ (BioTEC), agreement № S-A-UEI-23-14.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, V.K. and G.G.; methodology, T.H., S.K.; software, S.K., T.H.; validation, S.P., M.K.; formal analysis, S.P. and I.H.; resources, I.H.; data curation, M.K. and S.K.; visualization, J.G., S.T.; project administration, S.T.; funding acquisition, M.K.; supervision, T.H.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nadykto, V., Golub, G., Hutsol, T. et al. Optimization of the parameters of tillage units. Sci Rep 15, 10074 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94769-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94769-6