Abstract

People who inject drugs (PWID) are at higher risk of hepatitis C virus (HCV) due to their behaviors such as shared injection. Employing appropriate modeling approaches is crucial for accurately evaluating the impact of other variables on outcomes, in this case, HCV seropositivity. This study aimed to assess the non-linear effect of injection duration on HCV seropositivity. From July 2019 to March 2020, 2,684 PWID in Iran were recruited. The binary outcome variable was HCV serostatus (positive vs. negative), determined by detecting HCV antibodies. The non-linear effect of injection duration on HCV seropositivity was assessed using a multilevel Generalized Additive Model in R software, adjusting the effects of other variables in the analysis. We found a non-linear effect of injection duration on HCV seropositivity status (p-value < 0.001). The probability of HCV seropositivity increased with injection duration, though this relationship was non-linear. Initially, the probability rises faster; however, this effect diminishes as the injection duration extends. An initial sharp increase in HCV risk was seen during the first 20 years of injection. HCV seropositivity was notably associated with ever HIV seropositivity (OR [Odds Ratio] = 10.54, 95% CI [Confidence Interval]: 5.39, 20.61, p-value < 0.001), ever having injected methamphetamine (OR = 1.72, 95% CI: 1.33, 2.22, p-value < 0.001), being currently married (OR = 0.67, 95% CI: 0.48, 0.93, p-value = 0.018), ever shared needle/syringe with others (OR = 2.63, 95% CI: 1.32, 5.22, p-value = 0.006), and ever being incarcerated (OR = 1.97, 95% CI: 1.50, 2.58, p-value < 0.001). Our study contributes to the field by demonstrating that a non-linear approach can reveal patterns of risk that linear models might fail to capture. These findings indicate that the relationship between injection duration and HCV seropositivity can be more complex than previously understood, underscoring the importance of employing more advanced modeling techniques in future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) remains a significant public health challenge, particularly among key populations, such as people who inject drugs (PWID)1. In 2022, approximately one million new HCV infections were recorded worldwide, with 43.6% attributed to PWID due to unsafe injecting2. PWID are exposed to various and changing risk environments and are at risk of multiple harms related to injecting drug use. There are approximately 14.8 million PWID globally, constituting approximately 0.29% of the global adult population aged 15–643. The global prevalence of HCV among PWID is notably high, exceeding 40%. This equates to an estimated 5.6 million individuals who have recently injected drugs and are living with HCV4, with approximately 44.8% of these cases occurring in regions such as the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR)5.

This high prevalence underscores the critical need for targeted interventions and practical strategies to reduce the burden of HCV within these vulnerable groups. Injection drug use is not only a primary route of HCV transmission but also contributes to a spectrum of health issues, including HIV, hepatitis B virus (HBV), and various other blood-borne diseases6. Among these, HCV is particularly concerning due to its potential to cause chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma7.

The prevention of HCV among PWID is hindered by inadequate harm reduction services, restrictive drug policies, limited healthcare access, low testing rates, direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy restrictions, and insufficient government support4. Despite advancements in treatment options, including the introduction of DAA, which offers a high cure rate, the incidence of HCV among PWID remains persistent7. This persistence is partly due to the challenges associated with controlling the behaviors that facilitate transmission, such as sharing injection equipment8,9.

Iran has one of the highest populations of PWID in the EMR10, with 46.5% of PWID being HCV antibody reactive11. Despite the scale-up of harm reduction programs, including the provision of clean syringes and opioid agonist therapy, the control of HCV among PWID remains suboptimal12. To achieve the World Health Organization’s HCV elimination goals by 2030, PWID are identified as a priority population for improving prevention, testing, linkage to care, treatment, and follow-up care4,13,14. To achieve the goal of HCV elimination among PWID, it is crucial to identify the factors influencing the implementation of effective interventions.

Numerous studies have examined the determinants of HCV infection in this high-risk group, identifying factors such as age15, injection duration15, HIV co-infection16, homelessness17, needle sharing8, and incarceration history18. Previous studies have examined the linear effect of injection duration on HCV infection15,19. A notable limitation in many existing studies is their approach to modeling injection duration, often treating it as a linear predictor20 or categorizing it into arbitrary time intervals21,22,23,24. While simplifying the analysis, this approach may not adequately capture the complex, non-linear relationship between injection duration and HCV seropositivity. Linear models assume a constant increase in risk with each additional year of injection, which may overlook periods of accelerated risk or plateaus. Similarly, categorizing injection duration into broad time bands can obscure important variations within those intervals, leading to potential misestimation of the risk associated with different stages of an injection career.

Modeling approaches are essential for evaluating the economic and demographic impacts of disease epidemiology, estimating the effectiveness of interventions, and providing policymakers with precise information to inform decisions on infectious disease control25. Using the same data, the previous study assessed the risk factors associated with HCV, with injection duration included as a categorical variable19. This study mainly aimed to explore the non-linear relationship between injection duration and HCV seropositivity status among people who inject drugs in Iran. By investigating the relationship between drug injection duration and HCV seropositivity, this study seeks to address a critical gap in the existing literature to model time in the same studies.

Methods

Study overview and participant recruitment

Using respondent-driven sampling (RDS)26, from July 2019 to March 2020, 2684 PWID were recruited from 11 major cities in Iran, encompassing Tehran (sample size: 392), Tabriz (136), Sari (200), Mashhad (318), Yazd (127), Kermanshah (506), Khorramabad (306), Ahvaz (195), Shiraz (91), Kerman (171), and Zahedan (242), as part of the fourth national HIV bio-behavioral surveillance survey19. The study investigators strategically chose these cities in consultation with the Ministry of Health to represent diverse geographical regions within the country (Fig. 1).

RDS is a probability-based sampling technique developed by Douglas Heckathorn in 199727. It is particularly recognized for its use in AIDS prevention research among drug users. Unlike conventional snowball sampling, RDS includes a mechanism to document participants’ network sizes, enabling researchers to estimate inclusion probabilities and adjust the sample to represent the target population better28.

To be eligible for participation, individuals had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (i) be 18 years of age or older at the time of the interview; (ii) report illicit drug injection within the past 12 months; (iii) reside in one of the surveyed cities; and (iv) possess a valid referral coupon, except seeds. We selected a 12-month period to align our findings with previous survey rounds. Additionally, this duration is recommended by the WHO29. Participant involvement was confidential, with all individuals providing verbal informed consent for collecting biological and behavioral data before enrolling in the study. A gender-matched, face-to-face interview in a private room was conducted to gather behavioral data using a standardized questionnaire. Additionally, participants consented to do HCV and HIV testing, which included pre-test and post-test counseling. HCV testing was carried out using an HCV antibody rapid test (SD-Bioline, South Korea). HIV testing utilized the SD-Bioline, South Korea, rapid test, followed by confirmatory testing with the Unigold HIV rapid test if the first test was reactive. Test results were linked to survey responses through a unique code to ensure confidentiality, and no personally identifying information was requested or retained26.

Throughout the study, many efforts were made to ensure the highest possible quality. This included providing comprehensive training to interviewers, piloting the questionnaire, closely supervising observers during data collection, and ensuring that completed questionnaires were transmitted daily to the central server via an online system. The research team conducted daily quality checks to maintain the integrity of the work.

Study covariates and outcome

This analysis’s primary outcome of interest was HCV seropositivity status (positive vs. negative). The time lag from the drug injection to the interview time (as the detection time) was considered the main predictor variable. The principal emphasis of this modeling approach was to elucidate the non-linear association between the time since the onset of drug injection and the presence of HCV.

Some confounding variables also entered into the model, including sex (male vs. female), education (under high school vs. high school or more), marital status (single, currently married, divorced/widowed), HIV seropositivity status (positive vs. negative), ever injected methamphetamine (yes vs. no), lifetime history of homelessness (yes vs. no), public injecting in the last 12 months (yes vs. no), ever shared needle/syringe with others (yes vs. no), deprivation of health services due to drug use (yes vs. no), ever incarcerated (yes vs. no), and the first experience of drug use through injecting drugs (yes vs. no). The time since the onset of drug injection (year) was calculated as the current age minus the age at the first drug use.

Statistical analysis

In this study, a multilevel Generalized Additive Model (GAM) with a logit link function was employed to analyze the relationship between the predictor variables and the binary outcome of interest. These models allow for the inclusion of non-linear relationships between predictors, the response variable, and the hierarchical structure of the data. The multilevel framework accounts for the potential clustering of observations within higher-level units, while the GAM component flexibly models non-linear associations30.

A binary generalized additive logistic regression model was formulated as follows:

,

where yij denotes the binary outcome for individual i (i = 1, 2, …, n) in cluster j (j = 1, 2, …, J), fk(zkij) represent the smooth, non-linear function of the k-th (k = 1, 2, …, q) covariate zkij for individual i in cluster j, \(\:\sum\:_{l=1}{\beta\:}_{l}{x}_{lij}\) (l = 1, 2, …, p) indicates the linear part of the model which associated with other independent variables (x1ij to xpij indicates the p independent variables), and β0 is constant, uj is the random effect for cluster j.

The multilevel generalized additive logistic model was fitted to the HCV seropositivity status by considering the smooth time since the onset of drug injection. This study considered the random intercept for city levels in the model. The PWIDs (first level) are nested within cities (second level).

The thin-plate spline was considered as spline function. The Effective Degrees of Freedom (EDF) measures the complexity or flexibility of the smooth function used in the model. The degree of smoothness is automatically determined using penalized likelihood estimation. The model optimizes a trade-off between good fit to the data (low bias) and avoiding overfitting (low variance). This is done using penalized regression splines, where a penalty term is added to control the roughness of the smooth function. In this context, it tells you how much the relationship between time since the onset of drug injection and HCV seropositivity deviates from linearity. A higher EDF suggests a more complex, non-linear relationship. First, the crude odds ratio (cOR) for each independent variable was assessed, considering the association of the injection duration. Subsequently, the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) was evaluated, accounting for all predictor and confounding variables in conjunction with the injection duration association. Two models were fitted: one excluding random effects and the other including them. The model comparisons used the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) to identify the most parsimonious model.

The overall RDS-adjusted estimates were reported for HCV prevalence in subgroups of PWID recruited in the 2020 survey, which considered network size and homophily within networks. RDS-adjusted estimates for HCV prevalence were calculated in RDS-Analyst. However, we use an unweighted model based on Avery, et al.31. They showed significant bias and unacceptably high type-I error rates for weighted models and recommended unweighted models. The chi-square and Mann-Whitney U tests were applied to compare the socio-demographic and behavioral characteristics of PWIDs among seronegative and seropositive HCV groups. All analysis was done using R software version 4.3.1. P-values less than 0.05 were considered as significant.

Results

Demographics

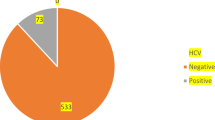

A total of 2,684 PWID with an average age of 40.2 (Standard Deviation [SD] = 9.3) years were recruited during the study period. Among them, 699 individuals (26.0%) were HCV seropositive. Most participants were male (96.6%). Most participants were divorced/widowed (38.3%), followed by single (36.6%) and currently married (25.0%). A majority had less than a high school education (69.1%), with a smaller percentage having completed high school or more (30.9%). On average, individuals in the combined group started using drugs at the age of 19.6 (SD = 5.1) years. The average duration of drug injection was 19.2 (SD = 9.1) years for seronegative and 24.5 (SD = 8.9) years for seropositive HCV participants. A small percentage (4.7%) of participants had their first drug use experience through injection. Among them, 56.6% reported a history of lifetime homelessness. Nearly half of the participants (46.6%) reported deprivation of health services due to drug use (Table 1).

HIV seropositivity

The data shows a higher prevalence of ever HIV seropositivity among individuals with seropositive HCV (9.6%) compared to those with HCV seronegative (1.41%) (P-value < 0.001) (Table 1).

Drug use behaviors

A prevalent behavior reported among participants was methamphetamine injection (34.2%). The prevalence was higher among those with HCV seropositivity (44.6%). A total of 18.9% of participants reported ever shared needle/syringe with others. For those with seronegative HCV, the percentage of ever shared needle/syringe was 13.3%, whereas it was higher at 34.6% among individuals with seropositive HCV (P-value < 0.001) (Tables 1 and 2).

Selection of the best model

The non-linear relationship between the duration since drug injection and seropositive HCV was found based on the observed probability of seropositive HCV in relation to the time since the onset of drug injection (Part A of Fig. 2). Model comparison was conducted using the BIC, with the model excluding random effects yielding a BIC of 1983.7 and the model including random effects showing a BIC of 1934.8. Given the lower BIC, the model with random effects was selected, and the corresponding results were reported.

Smoothed association of time since injection duration (years) on Hepatitis C virus (HCV) seropositivity among people who inject drugs (PWID) in 2020 national HIV bio-behavioral using a multilevel generalized additive logistic regression model. Part (A) Observed probability of seropositive HCV in relation to time since onset of drug injection. Parts (B) and (C) Smoothed estimates for the duration since the start of the drug injection. The time since the first injection drug has a non-linear relationship with the log odds as well as the odds of getting diagnosed with seropositive HCV. The shaded area measures the 95% confidence interval in the model estimate. In part (B), the univariate model illustrates the association of the injection period on HCV, considering only the injection period as the predictor variable. In part (C), the model demonstrates the association of the injection period on HCV while controlling for all independent variables.

Crude model

The crude analysis reveals several notable associations with HCV seropositivity. Specifically, the odds of HCV seropositivity was significantly lower among females (cOR = 0.49, 95% CI: 0.30, 0.82; p-value = 0.006), individuals with higher educational attainment (cOR = 0.72, 95% CI: 0.58, 0.89; p-value = 0.002), those who are married (cOR = 0.55, 95% CI: 0.42, 0.72; p-value < 0.001), and widows or divorced individuals (cOR = 0.77, 95% CI: 0.60, 0.99; p-value = 0.040) (Table 2).

Conversely, higher odds of HCV seropositivity were observed in PWID who tested ever positive for HIV (cOR = 8.82, 95% CI: 5.31, 14.65; p-value < 0.001), those with an ever injected methamphetamine (cOR = 2.32, 95% CI: 1.88, 2.86; p-value < 0.001), individuals with an ever being incarcerated(cOR = 2.39, 95% CI: 1.93, 2.96; p-value < 0.001), PWID with a history of homelessness (cOR = 1.24, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.52; p-value = 0.040), those who ever shared needle/syringe (cOR = 3.25, 95% CI: 2.10, 5.05; p-value < 0.001), and those who had deprivation of health services due to drug use (cOR = 1.25, 95% CI: 1.03, 1.53; p-value = 0.028) (Table 2).

Figure 2, part B, illustrates the smoothed estimates for the duration since the initiation of drug injection. The EDF of 3.12 indicates a non-linear relationship. The plot illustrates how the HCV seropositivity changes over time as drug injection duration increases. The association between the duration since the onset of drug injection and HCV seropositivity does not follow a simple linear pattern (p-value < 0.001).

Adjusted model

Holding other variables constant, PWID individuals who were currently married had a lower odds of HCV seropositivity (aOR = 0.67; 95% CI: 0.48, 0.93; p-value = 0.018) when compared to singles. Additionally, individuals who tested ever positive for HIV had a higher odds (aOR: 10.54; 95% CI: 5.39, 20.61; p-value < 0.001) for testing positive for HCV. Individuals who had an ever injected methamphetamine were at a higher risk of HCV seropositivity (aOR = 1.72; 95% CI: 1.33, 2.22; p-value < 0.001). Moreover, ever shared needle/syringe with others was associated with an elevated odds of HCV seropositivity (aOR = 2.63, 95% CI: 1.32, 5.22; p-value = 0.006). Lastly, PWID individuals with a history of ever being incarcerated had an aOR of 1.97 (95% CI: 1.50, 2.58; p-value < 0.001) for testing positive for HCV (Table 2).

The EDF of 2.01 indicates the non-linearity in this association, implying that the relationship between time since the onset of drug injection and HCV seropositivity is not linear (p-value < 0.001). Figure 2, part C, illustrates the smoothed estimates for the duration since the initiation of drug injection. This variable exhibits non-linear effects, as indicated by the observed proportions. Within the first 20 years following the initial injection, the probability of a positive HCV test exhibits an upward trajectory. The rate of increase diminishes as the injection duration lengthens.

Discussion

This study showed there is a non-linear association between the duration of injection drug use and HCV seropositivity among PWID. We also found that the odds of HCV transmission were higher among PWID who had ever shared needles/syringes, those who had ever tested positive for HIV, those who had ever injected methamphetamine, and those who had a history of incarceration. Conversely, those who were currently married had lower odds of HCV seropositivity.

We found a non-linear association between the duration of injection and HCV infection. In this regard, in the first 20 years after the start of injection, the odds of testing positive for HCV rises rapidly, indicating a period of heightened risk. However, following this initial surge, the rate of increase slows down. This enables us to capture the complex association between injection duration and HCV infection, highlighting periods of increased vulnerability and risk plateaus that linear models or categorical methods might overlook. However, previous studies have treated injection duration as a linear predictor20 or categorized it into time intervals21,22,23,24. The non-linear pattern indicates that the risk of HCV infection may accelerate after specific critical points in an individual’s injection career, possibly due to the cumulative effects of ongoing risky behaviors32 or the weakening of immune defenses over time33. An increase in HCV positivity among PWID during the first 20 years from the onset of injection can be explained by high-risk behaviors at the onset of drug use34, exposure to high-prevalence networks35, rapid transmission dynamics, frequent sharing of equipment, increased frequency of injection, and initial lack of knowledge. After 20 years, many individuals who are at high risk of contracting HCV may have already been exposed to and contracted the virus. Over time, PWID may become more aware of the risks associated with unsafe injection practices and adopt harm-reduction strategies, such as using sterile needles and avoiding sharing equipment.

Our study showed the association of injection-related behaviors and structural vulnerabilities in HCV transmission. Factors such as being single, ever shared needle/syringe with others, having ever injected methamphetamine, and a history of ever being incarcerated were all significantly associated with HCV seropositivity. These findings align with existing literature, which has identified that married PWID had a lower odds of HCV infection36. Methamphetamine injection is significantly associated with HCV seropositivity, highlighting the growing concern over stimulant injection as a key factor in the transmission of both HCV and HIV37. Also, needle sharing and incarceration have been identified as key risk factors for HCV infection among PWID18,38. The increased risk among those with the experience of imprisonment could be related to their behaviors outside and inside the prison. A higher prevalence of needle/syringe39 among this population and living in an environment40 with higher risk could be the main predictors of a higher prevalence of HCV among incarcerated people.

The study findings also highlighted the critical intersection of HIV and HCV among PWID. HIV infection was significantly associated with HCV seropositivity, reflecting the shared transmission routes and risk behaviors that contribute to the co-prevalence of these infections. The interaction between HIV and HCV is complex, with evidence suggesting that HIV co-infection accelerates HCV progression, leading to more severe liver disease and complicating treatment strategies41. Additionally, people living with HIV exhibit different rates of spontaneous HCV clearance compared to those without HIV, further complicating the clinical management of co-infected patients42. These findings underscore the importance of integrated care models that address both HIV and HCV in PWID, with a focus on improving testing, treatment access, and patient outcomes43.

This study had three limitations. First, the cross-sectional design of the survey imposes limitations on our ability to draw conclusions about causal relationships and the timing of events between HCV and the various determinants we are investigating. Specifically, because the data is collected at a single point in time, we cannot ascertain whether the determinants influenced the presence of HCV or if the infection affected these determinants. This lack of temporal sequencing restricts our understanding of the dynamics involved, making establishing any definitive cause-and-effect relationships challenging. Consequently, our findings may only reflect associations rather than true causal effects. Second, some behaviors were self-reported and thus subject to potential recall bias. Third, the associations of age and age at the first drug injection were not examined independently due to collinearity between these variables. Instead, the duration of injection—calculated as the difference between age and age at first drug injection—was utilized as a variable, indirectly capturing the association of age. This approach allows for an indirect assessment of HCV risk associated with age.

RDS effectively recruits hard-to-reach populations but has several limitations. These include potential biases from unequal network sizes and errors in measuring network size, which can affect weighting accuracy. It may not sufficiently address biases arising from unequal homophily among participants, resulting in skewed outcomes. Additionally, reliance on peer recruitment can introduce selection bias and limit generalizability, while estimating network size and handling non-response bias present significant challenges. Other concerns include transmission errors and recall issues when participants estimate their network size28,44,45,46. Nonetheless, RDS enhances traditional methods by incorporating random selection of venue-day-time units and peer referrals, making it more appropriate for populations lacking clear social networks. It also provides advantages such as access to hidden populations and reduced sampling bias, facilitating data collection that better represents the population and offers insights into social dynamics and community structures47. Another limitation is related to using the formula ‘current age minus age at first drug use’ to calculate injection duration, which could lead to misclassification bias, as participants may have had periods of abstinence during that time.

It is suggested to utilize a spatial random effect rather than a random intercept48. Incorporating spatial information may display spatial autocorrelation due to common socio-environmental factors. Geographically closer cities may exhibit more similar HCV prevalence rates due to shared healthcare resources, policies, or sociocultural norms. Future studies can also consider other significant HCV risk factors, such as blood transfusions or surgery before 1992.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study underscores the critical importance of addressing injection duration and associated risk behaviors to mitigate the ongoing HCV seropositivity among PWID. The non-linear relationship between injection duration and HCV seropositivity highlights the need for early intervention strategies, including needle exchange programs, HCV testing, and safe injection education, which should be prioritized to mitigate the rapid increase in HCV seropositivity observed during the initial years of drug injection. Additionally, the findings highlight the role of behavioral interventions aimed at reducing high-risk behaviors such as needle-sharing and methamphetamine use. Future research should continue to explore the complexities of this relationship and develop targeted strategies to address the specific needs of short-term injectors. By integrating these approaches into public health interventions, we can reduce the transmission of HCV and HIV among PWID, improve health outcomes for this population, and ultimately reduce the burden of these infections on society. Continued research is needed to explore the complex dynamics of HCV transmission further and refine intervention strategies that effectively mitigate these risks.

Data availability

The datasets analysed in the current study are not publicly available due [Data concerns privacy] but is available from the corresponding author on the reasonable request.

References

Grebely, J., Dore, G. J., Morin, S., Rockstroh, J. K. & Klein, M. B. Elimination of HCV as a public health concern among people who inject drugs by 2030–What will it take to get there? Afr. J. Reprod. Gynaecol. Endoscopy 20 (2017).

Organization, W. H. Global Hepatitis Report 2024: Action for Access in low-and middle-income Countries. (World Health Organization, 2024).

Degenhardt, L. et al. Epidemiology of injecting drug use, prevalence of injecting-related harm, and exposure to behavioural and environmental risks among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Lancet Global Health 11, e659–e672 (2023).

Day, E. et al. Hepatitis C elimination among people who inject drugs: challenges and recommendations for action within a health systems framework. Liver Int. 39, 20–30 (2019).

Aghaei, A. M. et al. Prevalence of injecting drug use and HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people who inject drugs in the Eastern mediterranean region: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Global Health 11, e1225–e1237 (2023).

Degenhardt, L. et al. Global prevalence of injecting drug use and sociodemographic characteristics and prevalence of HIV, HBV, and HCV in people who inject drugs: a multistage systematic review. Lancet Global Health. 5, e1192–e1207 (2017).

Blach, S. et al. Global change in hepatitis C virus prevalence and cascade of care between 2015 and 2020: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 7, 396–415 (2022).

Aitken, C. et al. The effects of needle-sharing and opioid substitution therapy on incidence of hepatitis C virus infection and reinfection in people who inject drugs. Epidemiol. Infect. 145, 796–801 (2017).

Mateu-Gelabert, P. et al. The staying safe intervention: training people who inject drugs in strategies to avoid injection-related HCV and HIV infection. AIDS Educ. Prev. 26, 144–157 (2014).

Mumtaz, G. R. et al. HIV among people who inject drugs in the middle East and North Africa: systematic review and data synthesis. PLoS Med. 11, e1001663 (2014).

Rajabi, A., Sharafi, H. & Alavian, S. M. Harm reduction program and hepatitis C prevalence in people who inject drugs (PWID) in Iran: an updated systematic review and cumulative meta-analysis. Harm Reduct. J. 18 (2021).

Mirzazadeh, A. et al. An on-site community-based model for hepatitis C screening, diagnosis, and treatment among people who inject drugs in Kerman, Iran: the Rostam study. Int. J. Drug Policy. 102, 103580 (2022).

Artenie, A. et al. Incidence of HIV and hepatitis C virus among people who inject drugs, and associations with age and sex or gender: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 8, 533 (2023).

Mahmud, S. et al. The status of hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs in the middle East and North Africa. Addiction 115, 1244–1262 (2020).

Artenie, A. A. et al. Diversity of incarceration patterns among people who inject drugs and the association with incident hepatitis C virus infection. Int. J. Drug Policy 96, 103419 (2021).

Lambdin, B. H. et al. Prevalence and predictors of HCV among a cohort of opioid treatment patients in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. Int. J. Drug Policy 45, 64–69 (2017).

Arum, C. et al. Homelessness, unstable housing, and risk of HIV and hepatitis C virus acquisition among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. infection 3, 6 (2021).

Stone, J. et al. Incarceration history and risk of HIV and hepatitis C virus acquisition among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 18, 1397–1409 (2018).

Khezri, M. et al. Hepatitis C virus prevalence, determinants, and cascade of care among people who inject drugs in Iran. Drug Alcohol Depend. 243, 109751 (2023).

Bautista, C. T. et al. Effects of duration of injection drug use and age at first injection on HCV among IDU in Kabul, Afghanistan. J. Public Health 32, 336–341 (2010).

Kawambwa, R. H., Majigo, M. V., Mohamed, A. A. & Matee, M. I. High prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and C viral infections among people who inject drugs: a potential stumbling block in the control of HIV and viral hepatitis in Tanzania. BMC Public. Health 20, 1–7 (2020).

Mateu-Gelabert, P. et al. Hepatitis C virus risk among young people who inject drugs. Front. Public. Health 10, 835836 (2022).

Havens, J. R. et al. Individual and network factors associated with prevalent hepatitis C infection among rural Appalachian injection drug users. Am. J. Public Health 103, e44–e52 (2013).

Eckhardt, B. et al. Risk factors for hepatitis C seropositivity among young people who inject drugs in new York City: implications for prevention. PLoS One 12, e0177341 (2017).

Sharhani, A. et al. Incidence of HIV and HCV in people who inject drugs: a systematic and meta-analysis review protocol. BMJ Open. 11, e041482 (2021).

Solomon, S. S. et al. Respondent-driven sampling for identification of HIV-and HCV-infected people who inject drugs and men who have sex with men in India: a cross-sectional, community-based analysis. PLoS Med. 14, e1002460 (2017).

Heckathorn, D. D. Respondent-driven sampling: a new approach to the study of hidden populations. Soc. Probl. 44, 174–199 (1997).

Raifman, S., DeVost, M. A., Digitale, J. C., Chen, Y. H. & Morris, M. D. Respondent-driven sampling: a sampling method for hard-to-reach populations and beyond. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 9, 38–47 (2022).

Organization, W. H. Guidance To Identify Barriers in Blood Services Using the Blood System self-assessment (BSS) Tool. (World Health Organization, 2023).

Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Generalized additive models: some applications. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 82, 371–386 (1987).

Avery, L. et al. Unweighted regression models perform better than weighted regression techniques for respondent-driven sampling data: results from a simulation study. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 19, 1–13 (2019).

Phillips, K. A. et al. Substance use and hepatitis C: an ecological momentary assessment study. Health Psychol. 33, 710 (2014).

Liu, L. et al. Acceleration of hepatitis C virus envelope evolution in humans is consistent with progressive humoral immune selection during the transition from acute to chronic infection. J. Virol. 84, 5067–5077 (2010).

Yilin, D., Bellerose, M., Borbely, C. & Rowell-Cunsolo, T. L. Assessing the relationship between drug use initiation age and Racial characteristics. J. Ethn. Subst. Abuse, 1–15 (2023).

Weeks, M. R., Clair, S., Borgatti, S. P., Radda, K. & Schensul, J. J. Social networks of drug users in high-risk sites: finding the connections. AIDS Behav. 6, 193–206 (2002).

Kassaian, N. et al. Hepatitis C virus and associated risk factors among prison inmates with history of drug injection in Isfahan, Iran. Int. J. Prev. Med. 3, S156 (2012).

Cepeda, J. A. et al. Estimating the contribution of stimulant injection to HIV and HCV epidemics among people who inject drugs and implications for harm reduction: a modeling analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 213, 108135 (2020).

Hagan, H. et al. Attribution of hepatitis C virus seroconversion risk in young injection drug users in 5 US cities. J. Infect. Dis. 201, 378–385 (2010).

Seyedalinaghi, S. A. et al. Prevalence of HIV in a prison of Tehran by active case finding. Iran. J. Public. Health. 46, 431–432 (2017).

Zafarghandi, M. B. S., Eshrati, S., Arezoomandan, R. & Farnia, M. Substance use and the necessity for harm reduction programs in prisons: A qualitative study in central prison of Sanandaj, Iran. Int. J. High. Risk Behav. Addict. 10 (2021).

Liberto, M. C. et al. Virological Mechanisms in the Coinfection between HIV and HCV. Mediators of inflammation 2015, 320532 (2015).

Smith, D. J., Jordan, A. E., Frank, M. & Hagan, H. Spontaneous viral clearance of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection among people who inject drugs (PWID) and HIV-positive men who have sex with men (HIV + MSM): a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 16, 1–13 (2016).

Organization, W. H. Consolidated Guidelines on HIV, Viral Hepatitis and STI Prevention, Diagnosis, Treatment and Care for Key Populations. (World Health Organization, 2022).

Rudolph, A. E., Fuller, C. M. & Latkin, C. The importance of measuring and accounting for potential biases in respondent-driven samples. AIDS Behav. 17, 2244–2252 (2013).

Lee, S., Suzer-Gurtekin, T., Wagner, J. & Valliant, R. Total survey error and respondent driven sampling: focus on nonresponse and measurement errors in the recruitment process and the network size reports and implications for inferences. J. Official Stat. 33, 335–366 (2017).

Bernard, J., Daňková, H. & Vašát, P. Ties, sites and irregularities: pitfalls and benefits in using respondent-driven sampling for surveying a homeless population. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 21, 603–618 (2018).

Navarrete, M. S., Adrian, C. & Bachelet, V. C. Respondent-driven sampling: advantages and disadvantages from a sampling method. Medwave 21 (2022).

Hadianfar, A., Küchenhoff, H., MohammadEbrahimi, S. & Saki, A. A novel Spatial heteroscedastic generalized additive distributed lag model for the Spatiotemporal relation between PM2. 5and cardiovascular hospitalization. Sci. Rep. 14, 29346 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank the survey participants for generously dedicating their valuable time to our study. We also thank the research team and national and subnational organizational stakeholders for their invaluable support in preparing and executing the study.The project was supported by the Center for Communicable Disease Control and Prevention of Iran’s Ministry of Health and Medical Education and the National Institute for Medical Research Development (NIMAD 973382). We would like to acknowledge support from the NationalInstitute on Drug Abuse (grant number 5R37DA015612–170).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FT and SM contributed to data preparation. HSh and SH performed data analysis and interpretation. HSh and SH provided the draft of the manuscript. All authors read and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical considerations

All research protocols underwent a thorough review and received approval from the Kerman. University of Medical Sciences ethics committee (Ethics Codes: IR.KMU.REC.1397.573). Participation was anonymous. Before enrolling in the study, all participants provided verbal informed consent for biological and behavioral data collection. All research was performed in accordance with relevant regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Haji-Maghsoudi, S., Tavakoli, F., Mehmandoost, S. et al. The association between drug injection duration and hepatitis C prevalence among people who inject drugs in Iran. Sci Rep 15, 10208 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94867-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94867-5