Abstract

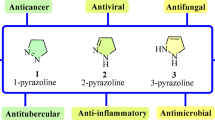

4-Aminocoumarins are significant in organic synthesis as key building blocks for various heterocyclic structures with pharmacological importance. This study focuses on synthesizing phenyliodonium derivatives of 4-aminocoumarins (T1-T6) and evaluating their broad-spectrum biological properties, including antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, antioxidant, cytotoxicity, and wound-healing properties. The compounds synthesized were structurally confirmed through UV-Vis, GC-MS, 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR, FT-IR, melting point, and CHNS analysis. The in vitro antibacterial and antifungal activities of these compounds were assessed against eight bacterial strains and five plant fungal pathogens. The antiviral property was evaluated by measuring the reduction in cytopathic effects of Dengue virus type-2 in BHK-21 cells. Cytotoxicity testing on human epidermal keratinocyte cells using the MTT assay at concentrations ranging from 1 to 100 µg/mL revealed that none of the compounds exhibited significant cytotoxic effects. Additionally, ADME/Toxicity, molecular docking, antioxidant, and wound-healing studies were examined, further supporting the therapeutic potential of these compounds. Most of the synthesized phenyliodonium derivatives demonstrated broad-spectrum antibacterial and antifungal activities. Among them, Compound T6 exhibited the most potent antimicrobial activity, as indicated by its MIC₉₀ and MBC values, demonstrating superior efficacy compared to ciprofloxacin. The antiviral test against Dengue virus type-2 showed minimal effects with a cytopathic effect reduction of 10–13% at non-toxic concentrations. These compounds exhibited broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity coupled with minimal cytotoxicity, highlighting their potential as promising candidates for developing novel therapeutic agents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria, a direct result of mutation, gene transfer, and inappropriate antimicrobial use, presents an immediate and severe threat to global health1. Similarly, the widespread occurrence of phytopathogenic fungi-induced plant diseases is a global menace to food security and crop protection2. The quest for innovative compounds with antifungal properties for use in agriculture or forestry is a compelling and urgent need in light of the global threat posed by phytopathogenic fungi-induced plant diseases3. The lack of effective treatments or vaccines for most viral infections necessitates the development of new therapeutic strategies that fine-tune immune responses to combat the virus while avoiding severe immunopathology4. Dengue virus, a mosquito-borne member of the Flaviviridae family, is a prominent example5. Commercially available antimicrobials are of microbial or plant origin. The biosynthetic gene cluster of a particular antibiotic also contains genes responsible for resistance to the same antibiotic. Pathogenic microbes may acquire these resistance genes from antibiotic producers mainly through horizontal gene transfer. Thus, this situation necessitates a novel strategic approach for preventing infectious diseases using new bioactive that do not rely on existing microbial origin6.

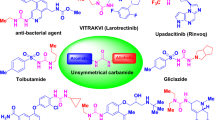

The synthesis of new bioactive coumarin derivatives with highly active functional groups provides a novel insight into combating antimicrobial resistance due to the interesting physicochemical properties and pharmacological relevance of these compounds. Coumarins are a benzopyrene class of natural organic heterocyclic compounds exhibiting diverse biological activities, including antibacterial7, anti-inflammatory8, antiviral9, antifungal10, antidiabetic11, antioxidant12, anticancer13, anticonvulsant14, anticoagulant15, neuroprotection16 and enzyme-inhibitory activities17. Heterocyclic compounds are of critical importance in medicinal chemistry due to their diverse biological activities, structural versatility, and their presence as key scaffolds in numerous clinically approved drugs18,19. Compounds with a coumarin moiety have demonstrated remarkable efficacy in disease treatment20,21,22, with over 1300 coumarins identified as secondary metabolites in plants, fungi, and bacteria23,24,25. Furthermore, synthetic coumarins, characterized by diverse substituents at the C-3, C-4, and C-7 positions, have undergone extensive screening for their biological properties26,27. Only a few studies have investigated the biological activity of coumarins substituted with amino groups. The mode of action of aminocoumarin derivatives as antimicrobial agents varies from that of other antimicrobials according to their target of action, which, in turn, can be used as a new combinational approach to treat infectious diseases caused by MDR species.

Although aminocoumarins are not well known for their antioxidant properties, investigating coumarins as antioxidants has gained attention. This is attributed to their versatile ability to scavenge free radicals, modulate enzymatic processes, and form chelate complexes with metal cations12. The oxidative characteristics of these compounds are intricately linked to their molecular structure, whether coumarins act as antioxidants or prooxidants28. When administering specific coumarin derivatives alongside vitamins and other antioxidants, it is crucial to consider their oxidative behavior and the nature of oxidative stress. This consideration becomes pivotal in understanding the healing process, where the interplay of coumarins with oxidative stress is a key determinant.

Furthermore, coumarin derivatives, particularly synthetic ones, have potential in wound management by preventing microbial colonization, promoting healing, and addressing the challenges of methicillin-resistant S. aureus infections. Antimicrobial agents with antioxidant and angiogenic properties, along with the capacity to stimulate collagen synthesis and cell proliferation, play crucial roles in enhancing the wound-healing process29.

An ideal drug candidate must exhibit efficient absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion while considering toxicity and ADMET properties. In silico techniques, including ADMET and drug-likeness prediction, play crucial roles in identifying compounds with anticipated biological activities30. Clinical trials have witnessed drug failure due to adverse side effects and proven toxicity, incurring substantial costs in the drug development process31.

The current study underscores the potential transformative impact of a synthetic production strategy for the chemical synthesis of 4-aminocoumarins and various phenyliodonium derivatives of 4-aminocoumarins. It involves structural characterization, evaluation of antimicrobial potentials, assessment of antioxidant properties, and in silico ADME/Toxicity and molecular docking studies. Additionally, this research represents a preliminary exploration of the wound-healing potential inherent in synthetic coumarin derivatives, offering hope for developing novel therapeutic agents.

Results

Chemistry and structural validation of synthetic coumarin derivatives

The compounds were synthesized following the pathways described by Papoutsis et al. (1996), and their purity was first checked with thin-layer chromatography. The recrystallization process was carried out in each step using an ethanol-water mixture in a 3:1 ratio, which was optimized based on the solubility of the compounds. This specific ratio provided an effective balance between solubility at higher temperatures and precipitation upon cooling, leading to improved purity. This process significantly enhanced purity, though a moderate yield reduction occurred due to material loss during filtration and washing. However, this trade-off ensured high-quality final products, confirmed by column chromatography, UV-visible, IR, NMR, CHNS, and MS.

Figure S1 (Supplementary Fig. S1) indicates FTIR spectra recorded at room temperature from 4000 to 400 cm− 1, using JASCO FT/IR 4700 type A equipped with a TGS detector for the six compounds. Figure S1A indicates the IR spectra of 4-AC. The observed amino frequencies at 3394 and 3219 cm− 1 exhibit a notable reduction compared to their theoretically predicted values, attributed to the development of strong hydrogen bonds within the solid state. The C=O band is the strongest in the spectrum detected at 1634 cm− 1. The C-N stretching vibrations were predicted to be near 1400 cm− 1 and measured at 1438 cm− 132. Detailed knowledge of the spectral behavior of the other five derivatives has not yet been studied. One of the objectives of this current study is to unveil the structure through CHNS analysis, UV, MS, NMR, and IR spectroscopic features. The N-H stretching vibrations in 4-A-3-PIC T were observed at 3340 cm− 1 (Figure S1B). Aromatic C–H stretching vibrations are usually observed between 3100 and 3000 cm− 1. These vibrations aren’t much affected by substituents in this range. The C–H vibration bands in heterocyclic compounds are usually weak33,34. 1680, and 1643 cm− 1 bands indicate -C=C- stretching, C=O vibrations, and bands between 1251 and 1029 cm− 1 indicate CCH in-plane bending vibrations in Figure S1B35. The heterocyclic amine stretch in 3-PIC-4-I was observed at 3410 cm− 1 (Figure S1C). The N-H stretch in 4-A-3-PIC indicates the presence of secondary amine, observed at 3300 cm− 1 in Figure S1D. The peak at 3280 cm− 1 indicates the presence of an aromatic ring in Figure S1E. The peak at 1695 cm− 1 indicates the presence of conjugated ketone in 4-DPA-3-IC (Figure S1F)36. The C=O stretching vibration is observed between 1850 and 1550 cm− 1, appearing as a medium or strong band in all derivatives. Its position is influenced by neighboring substituents, conjugation, hydrogen bonding, and the physical state37. The C-C stretching bonds in the aromatic ring structures are observed within the spectral region of 1625–1430 cm− 135.

Mass spectra obtained for the synthesized derivatives using the GC-MS analysis are represented in Fig. S2 and S3. GCMS profile for 4-A-3-PIC T was ionized into three fractions (Fig. S2). The first fraction with a base peak at a m/z ratio 218 indicates the presence of iodobenzene at a retention time of 9.530 min. The second fraction was obtained with a base peak at an m/z ratio of 171 within a retention time of 22.805 min. The third fraction is characterized as 4-AC with a base peak at an m/z ratio of 161 within a retention time of 30.615 min. A separate individual GCMS profile of 4-AC was represented in Fig S3A with a m/z ratio of 161 within a retention time of 30.710 min. Fig. S3 B-E represents the mass spectra of 3-PIC-4-I, 3-I-4-PAC, 4-PAC, and 4-DPA-3-IC. Compounds 3-PIC-4-I and 3-I-4-PAC had the same m/z ratio of 363 at different retention times, such as 35.325 and 23.100 min, respectively. The base peak 237 represents the m/z ratio of 4-PAC (Fig. S3D) and 423 represents the m/z ratio of 4-DPA-3-IC (Fig. S3E).

The UV–Vis spectrum of six different synthetic derivatives was measured in DMSO solution using a UV/Vis Perkin-Elmer Lambda 365 spectrophotometer at room temperature (Fig. S4). Significant absorption maxima were detected within the wavelength range of 200 to 400 nm, characteristic of the ultraviolet region.

At room temperature, the 1H and 13C NMR spectra of the synthesized compounds were measured on a JEOL (JNM-ECZ500R) instrument. The values of the chemical shifts are expressed in δ values (ppm) and the coupling constants (J) in hertz. The experimentally determined 1H and 13C chemical shift peaks were recorded in DMSO-d6 (Fig. S5 and S6) using TMS as an internal reference. The non-integrated familiar peaks at δ 2.4 and 3.3 ppm in Fig. S5 represent water and solvent peaks in all the 1H spectrums. The 1H NMR spectrum of compound 4-AC revealed the presence of a d (doublet) signal at δ 7.97 ppm corresponding to one H in the benzopyran ring and s (singlet) signal at δ 5.20 ppm assigned to the CH group of this ring (Fig. S5A). Fig. S5B represents the 1H NMR spectra of the compound 4-A-3-PIC T in which δ 8.24–7.07 ppm indicates aromatic m (multiplet) H atoms and δ 2.24 ppm indicates s, 3 H in the methyl group of tosylate ion. δ 8.03–6.88 ppm in Fig S5C represents the dd and m signals of aromatic H in 4-A-3-PIC.

The appearance of a singlet signal at approximately 5.26 ppm in compound 3-I-4-PAC verified the presence of the NH group (Fig. S5D). The structure of 4-PAC was confirmed with a singlet signal at δ 5.55 and 5.39 ppm, representing the NH and CH group in the benzopyran ring of the compound (Fig. S5E). 1H-NMR spectrum for the compound 4-DPA-3-IC is represented in Fig. S5F, in which d, m signals were recorded at δ 7.94–5.17 ppm, indicating the presence of aromatic H atoms. 13C NMR spectra for 4-AC, 4-A-3-PIC T, 3-PIC-4-I, and 3-I-4-PAC are represented in Fig. S6 and S7 with the chemical shift values for the structure elucidation of synthesized derivatives.

Elemental analysis profiles for 4-AC, 4-A-3-PIC T, 3-PIC-4-I, and 3-I-4-PAC are represented in Fig. S8, indicating each elemental percentage in the compound such as Carbon (C), Hydrogen (H), Nitrogen (N), and Sulphur (S). The occurrence of s is exclusively identified in 4-A-3-PIC T, indicating the existence of the tosylate ion. Fig. S1-S8 was given in the supplementary material for further reference.

ADME and toxicity studies

The bioavailability radar serves as a preliminary tool for assessing a molecule’s suitability as a drug candidate (Fig. 1). Within the highlighted pink zone, specific properties align with optimal drug-like characteristics: lipophilicity (Log Po/w ranging from − 0.7 to + 5.0), size (molecular weight between 150 and 500 g/mol), polarity (Topological Polar Surface Area (TPSA) between 20 and 130 Å2), solubility (log S not more than 6), saturation (fraction of carbons in sp3 hybridization not below 0.25 (Fraction Csp3)), and flexibility (restricted to no more than nine rotatable bonds)38. From Fig. 1, it is evident that all the compounds have a fraction of Csp3 below 0.25. Table 1 lists the other significant ADMET parameters of the synthesized compounds. The logarithmic partition coefficient between n-octanol and water (log Po/w) is a classical metric for determining lipophilicity39. The solubility of a molecule has considerable significance in various aspects of drug development, notably in facilitating handling and formulation. In drug discovery endeavors focused on oral administration, solubility emerges as a pivotal factor influencing absorption40. Human intestinal absorption (HIA) is a key ADMET property, playing a vital role in the transportation of drugs to their intended targets30.

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) predicts various central nervous system (CNS) vasculature features. The unique properties of CNS vessels, such as the absence of pores in endothelial cells and regulatory mechanisms for the transport of ions, molecules, and cells, create a highly restrictive environment that hinders the delivery of compounds into the central nervous system41. The P-glycoprotein substrate, a compound using the P-glycoprotein transporter for activities like drug excretion and absorption, is integral to understanding ADMET behavior42. Understanding whether compounds serve as substrates or non-substrates for permeability glycoprotein (P-gp), a crucial member of ATP-binding cassette transporters (ABC-transporters), is essential for evaluating active efflux across biological membranes, such as from the gastrointestinal wall to the lumen or within the brain43. Lipinski’s “Rule of Five,” encompassing molecular weight (MW ≤ 500), hydrogen donors (≤ 5), rotatable bonds (≤ 10), LogP (≤ 5), and acceptors (≤ 10), is a conventional benchmark in drug design and screening. All compounds in Table 1 under scrutiny adhere to Lipinski’s rule of five, barring two exceptions with one violation for each of the compounds, such as 4-A-3-PIC T exceeds the prescribed molecular weight, and 4-DPA 3-IC exhibits a lower log P value, signifying their adherence to drug-like characteristics. A concession of up to two violations of Lipinski’s rule is deemed acceptable for an orally active compound44. Human intestinal absorption (HIA) and Caco-2 permeability play critical roles in scrutinizing the absorption of drug lead molecules45. The compounds in Table 1 demonstrate high gastrointestinal absorption, suggesting 100% HIA in the intestines but only moderate permeability to Caco-2 cells. A Total polar surface area (TPSA) ≤ 130 indicates high oral bioavailability. Predictive outcomes revealed favorable blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability for all target compounds except 4-A-3-PIC T. Minnow toxicity, assessed by lethal concentration (LC50) values, denotes high acute toxicity if the value is below − 0.346. Organic synthesis PAINS (Pan Assay Interference Assay) yields zero alerts for all compounds (Table 1), affirming the absence of problematic pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic issues associated with functional groups during developmental stages47. Synthetic accessibility is pivotal in selecting the most promising virtual molecules for subsequent synthesis and biological assays or experiments. A comprehensive assessment of preADMET and SwissADME underscores the promising drug candidate attributes of the target compounds. Collectively, these properties contributed to the extensive study of drug ADMET behavior.

In silico molecular docking studies

Based on inhibitor binding mechanisms and crystal structure resolution, the PDB structures of several protein targets—bacterial, fungal, and viral—were virtually selected and screened from the RCSB Protein Data Bank. Synthetic derivatives were rated further after docking into the target proteins’ active regions (Fig. 2) according to interactions and the overall docking score (Table 2).

Antibacterial activity

The antibacterial activity of synthesized compounds against different Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria in the agar well diffusion method is represented in Fig. S9. The middle well in each Petri plate without any inhibition zone represents the negative control, DMSO. Table 3 shows the measured diameter of the inhibition zone for each compound. A. baumannii, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus showed activity in almost all synthesized compounds. MIC and MBC were calculated for those compounds that obtained ≥ 20 mm ZOI in the agar well diffusion method. Figure 3 is the graphical representation of MIC90 calculated for the compounds with significant antibacterial activity. The compound 4-PAC shows antibacterial activity against A. baumannii, E. coli, and S. aureus at MIC90 8, 9, and 10 µg/mL respectively. The compound 4-DPA-3IC shows antibacterial activity against all the test organisms with an MIC90 range of 5–11 µg/mL. The MBC values for this compound were also calculated for all the test bacteria and found to be around 40–80 µg/mL (Fig. S14). The compound 4-3-PIC T shows antibacterial activity against E. coli and B.substilis at MIC90 5 µg and 10 µg/mL, respectively. The compound 3-I-4-PAC shows antibacterial activity against B.substilis, K.pneumoniae, P. mirabilis, S. aureus, and S. typhimurium at MIC90 10, 9, 10, 6, and 10 µg/mL respectively. The compound 3-PIC-4-I shows antibacterial activity against S. aureus with MIC90 10 µg/mL. Ciprofloxacin was used as a positive drug control for the study with a calculated MIC of 4 µg/mL48.

Antifungal activity

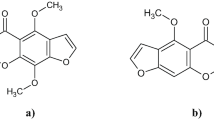

To evaluate the tolerance of the antifungal activity, the duration of 3, 5, and 7 days were considered, respectively. It was found that the inhibition rate had slightly changed with a longer duration. Compounds 4-AC (T1),4-3-PIC T (T2), 3-I-4-PAC (T4), and 4-DPA-3IC (T6) showed activity against F. solani, in which T2 and T6 exhibited more excellent antifungal activity than the positive control 5-FC (Fig. S10). Fig. S11 represents the activity of synthesized compounds against F. oxysporum (7th day of incubation) and C. albicans (24 h). The compounds T1-T6 exhibited poor activity against C.albicans. T1 showed higher activity against F. oxysporum than 5-FC. T3 and T6 showed almost similar activity to that of 5-FC. Fig. S12 represents the activity of T1, T3, T4, and T6 against A. niger on the 7th day of incubation. The compounds T1, T3, and T4 showed the best antifungal activity against A. niger with a % inhibition growth of 59.61 ± 0.73, 72.77 ± 0.74, and 75.98 ± 0.73, respectively. Compounds T1, T2, and T6 showed good antifungal activity against P. chrysogenum (Fig. S13). PDIG values were measured for target compounds with good antifungal activity for the test organisms used, and the observations were given in Table 4 and graphically represented in Fig. 4.

Antiviral activity

Before the antiviral assay, the maximal non-toxic dose of synthesized compounds (T1-T6) in BHK-21 cells was established. Among the compounds, T5 and T6 showed the lowest MNTD at 0.1 µg/mL, indicating they are relatively less safe than the other derivatives. In contrast, T1 exhibited the highest MNTD at 2.5 µg/mL. The MNTD values for T2, T3, and T4 were nearly identical, each at 1 µg/mL. The CPE reduction assay revealed that compounds T1, T5, and T6 did not exhibit significant inhibition of cytopathic effects (Fig. 5A). In contrast, compounds T2, T3, and T4 showed minimal antiviral activity, with inhibition levels of up to 12%, compared to the positive control, castanospermine, which is having 68% reduction in cytopathic effects (Fig. S15).

Antioxidant activity

The synthesized compounds were examined for their antioxidant potential using the DPPH free radical scavenging assay, with ascorbic acid as the reference drug. The graph in Fig. S16 illustrates each compound’s calculated percentage inhibition of DPPH radical scavenging activity. The results highlighted that compound 4-A 3-PIC T (T2) demonstrated the highest antioxidant potency, with an IC50 value of ≥ 50 µg/mL.

Cytotoxicity assessment using MTT assay

Cytotoxicity was assessed for the normal HaCaT cell line exposed to different concentrations of synthetic coumarin derivatives by performing an MTT assay. The compounds T1, T5, and T6 exhibited very low percentages of cell death even at higher concentrations of drug administration, such as 100 µg/mL, indicating the nontoxic behavior of target compounds to normal cells. The compounds T2, T3, and T4 showed more than 60% cell death in the HaCaT cell line when treated with 100 µg/mL (Fig. 5B). So, the lower concentrations of the respective compounds were tested again to determine the IC50 value (Fig. S17). The observed IC50 values for the synthesized compounds with standard error (SE) are given in Table 5.

In vitro scratch wound healing studies

The in vitro scratch wound assay showed that synthetic coumarin derivatives at a concentration of 10 µg/mL (≅ MIC90) caused a lot of cell migration within scratches in HaCaT cells (Fig. 6b). Compared to controls, the cell monolayer scratch exhibited partial closure within 24 h of exposure to HaCaT cells treated with the synthetic compounds. Images captured at intervals substantiated the non-toxic nature of the synthetic derivatives, promoting effective cell migration for wound closure49. The closure of the artificial gap “scratch” on the confluent cell monolayer of HaCaT cells was observed, wherein cells at the gap’s edge moved towards the opening, facilitating scratch closure. This led to the re-establishment of new cell-cell contacts, distinguishing the test from the cell/DMSO control and 5-FU treated samples (Fig. 6a). The gap area, indicative of cell migration potential, was measured in µm2 for different synthetic compounds, 5-FU, DMSO control, and cell control at 0th, 24th, and 48th hours of incubation, and the results were graphically represented (Fig. S18). The results showed that the synthesized compounds had a wound-healing potential in the order 4-PAC > 3-PIC-4-I > 4-DPA-3-IC > 4-A-3-PIC T > 4-AC > 3-I-4-PAC.

Discussion

The compounds were synthesized according to the chemical pathways outlined in Schemes 1 to 650. The direct synthesis of 4-AC from primary amines was first developed by Joshi et al. based on the reaction of 4-hydroxycoumarin with ammonium acetate in acetic acid51. 4-A-3-PIC T was synthesized by the reaction of (hydroxy (tosyloxy) iodo) benzene and 4-AC in dichloromethane, which, upon basification, is converted to its conjugate acid, 3-PIC-4-I. The reaction proceeded quantitatively in refluxing acetonitrile to yield 4-A-3-PIC. Treatment with a palladium catalyst in triethylamine and tetrahydrofuran quantitatively affected the deiodination of the present compound. The resulting compound, 4-PAC, was then treated with diacetoxy iodobenzene to yield the only isolable product, 4-DPA-3-IC. The structural characterization of all synthesized compounds in each step was based on elemental analysis and spectral data (UV-visible, IR, NMR, and MS). A thorough evaluation using preADMET and SwissADME highlights the target compounds’ strong potential as drug candidates. These properties collectively supported the detailed investigation of their ADMET profiles. Compared to 4-AC, most of the derivatives exhibited enhanced antibacterial activity against the test organisms, indicating that strategic derivatization of aminocoumarins with potential functional groups holds promise as an effective approach to addressing bacterial infection. The compound 4-A 3-PIC T, utilizing tosyl groups as protective entities, exhibited moderate antibacterial properties. Furthermore, the antimicrobial significance of cyclic imide structures and their derivatives, serving as pivotal scaffolds for antimicrobial agents52 indicates the importance of compound 3-PIC-4-I as an antimicrobial agent. The results indicated the antimicrobial potential for the compounds in the order 4-DPA-3-IC > 3-I-4-PAC > 4-PAC > 4-A-3-PICT > 3-PIC-4-I, emphasizing the potential of strategic derivatization for effective antimicrobial development.

The electrophilic nature of the phenyliodonium group can lead to interactions with bacterial enzymes, disrupting essential redox homeostasis. This makes phenyliodonium-modified aminocoumarins potential candidates for antimicrobial and antifungal agents, especially against resistant strains. Phenyliodonium derivatives interact with DNA topoisomerases, and their addition to aminocoumarins enhances DNA gyrase B inhibition, improving antibacterial activity against S. aureus6. Additionally, the tosyl group may improve lipophilicity, facilitating better membrane permeability and increasing bioavailability. These structural modifications contribute to the observed enhancement in antibacterial activity compared to the parent 4-aminocoumarin scaffold. Compared to the antibacterial study, 4-AC and 4-DPA-3IC (MIC90 10 µg/mL) simultaneously showed broad-spectrum antifungal activity against the plant fungal pathogens, indicating their multitargeted activity with functional groups. The antiviral efficacy of the compounds was notably lower (12%) compared to the positive control, castanospermine, which achieved a 68% reduction in cytopathic effects. This indicates a need for further optimization of these derivatives to improve their antiviral potential.

Docking studies indicated that phenyliodonium-substituted coumarins showed stronger binding affinities to the target proteins than the basic structure of aminocoumarin, which was consistent with experimental findings. The phenyliodonium derivatives exhibited significantly enhanced antimicrobial activity, highlighting the importance of structural modifications in optimizing the antimicrobial potency of aminocoumarin derivatives for potential therapeutic applications.

The hypervalent iodine center in phenyliodonium compounds can undergo redox transformations, enabling the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) or acting as an oxidizing agent. The screening assay for antioxidant activity indicated that the synthesized molecules were less potent than the reference drug. Their administration, along with other antioxidants, has to be considered, taking into account the oxidative behavior of coumarin derivatives as prooxidants and the significance of oxidative stress for enhancing the antimicrobial and wound healing potential. The analysis of cytotoxicity, antimicrobial, and antioxidant test outcomes revealed that the compounds manifested antimicrobial and antioxidant activity at concentrations that did not induce cytotoxic effects. Hence, the antimicrobial effectiveness of these compounds appeared to be rooted in their selective targeting rather than eliciting a broad toxic impact. This observation underscores the potential of these compounds to specifically combat microbial threats without causing general cellular toxicity. The in vitro scratch wound assay demonstrated that the synthetic coumarin derivatives significantly promoted cell migration and wound closure in HaCaT cells, with 4-PAC showing the highest wound-healing potential. These findings suggest that the derivatives effectively enhance cell migration, supporting their potential for wound-healing applications.

The combination of aminocoumarin’s ability to inhibit bacterial and eukaryotic topoisomerases with the oxidative and electrophilic properties of phenyliodonium substitutions may lead to enhanced cytotoxic effects in cancer cells or more potent antimicrobial activity, distinguishing these derivatives from traditional coumarin-based drugs.

This study is limited by the narrow scope of antiviral testing, as only the Type 2 dengue virus was included due to time and resource constraints, restricting the number of viral strains tested and the extent of experimental validation. While molecular docking studies indicated promising binding affinities of the compounds with the selected viral targets, a more extensive experimental evaluation involving a broader range of viral strains would provide a more comprehensive assessment of their antiviral potential.

Methods

All reagents used for the synthesis were purchased from Merck, Sigma Aldrich, and Spectrochem. Infrared (IR) spectra were recorded at room temperature from 4000 to 400 cm− 1, using JASCO FT/IR 4700 type A equipped with a TGS detector. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a JEOL (JNM-ECZ500R) instrument at room temperature in DMSO-d6 (deprotonated Dimethyl Sulfoxide) using TMS (Tetramethylsilane) as an internal reference. The UV-visible absorption spectra of the compounds were recorded using a UV/Vis Perkin-Elmer Lambda 365 spectrophotometer at room temperature. Shimadzu GC-MS system with a TriPlus RSH autosampler and a DSQ II mass-selective detector (model number QP2010S) was used for the mass spectral characterization of the compounds. Melting points were determined in open capillaries using a Stuart SMP20 melting point apparatus. The Thermo Scientific FLASH 2000 HT analyzer was used for CHNS analysis. The integrated TCD (thermal conductivity detector) and dedicated Eager 300 software enabled the FLASH 2000 HT analyzer to function as a stand-alone instrument to determine the elemental weight percentages of N, C, H, and S.

General procedure of chemical synthesis with spectral data

Preparation of 4-aminocoumarins (T1)

A mixture of finely powdered 4-hydroxycoumarin (4-HC) (1.07 g, 0.0066 mol) and ammonium acetate (7.87 g, 0.100 mol) was melted in an oil bath (up to 130 ℃) and stirred for three hours (Scheme 1). After cooling, water was added, and yellow crystals were collected by simple filtration. The final product, 4-aminocoumarins (4-AC), was obtained by purifying these crystals through recrystallization from a mixture of ethanol and water in a 3:1 ratio, yielding 90.31% (0.96 g)53. Melting point (mp) 232–234 ℃32; IR (nujol): Vmax 3396, 3219, 1634, 1438 cm− 1; 1H NMR (500 MHz) (DMSO-d6): δ 7.97 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.57 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1 H), 7.37–7.27 (m, 2 H), 5.20 (s, 1 H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 161.7, 155.6, 153.7, 132.1, 123.2, 123.0, 116.8, 114.4, 83.8. Elemental analysis: Anal. Calcd. for C9H7NO2: C, 67.01; H, 4.34; N, 8.68. Found: C, 66.72; H, 4.38; N, 8.88.

Preparation of 4-amino-3-phenyliodoniocoumarin tosylate (T2)

Hydroxy (tosyl`) iodobenzene (1.96 g, 5 mM) was added to a stirring suspension of 4-aminocoumarin (0.805 g, 5 mM) in dichloromethane (30 mL) at room temperature until complete mixing was achieved. After one hour at room temperature, the resulting white solid was filtered, washed multiple times with dichloromethane (Scheme 2), and dried under vacuum to yield 2.48 g (93%) of the 4-amino-3-phenyliodoniocoumarin tosylate (4-A-3-PIC T); mp 190–194 °C; IR (nujol): Vmax 3340, 3210, 1680, 1645, 1180, 1160 cm-1;1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.24 (m,1 H), 8.03 (m, 2 H), 7.74–7.39 (m, 8 H), 7.07 (m,2 H), 2.24 (s, 3 H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 159.2, 158.3, 153.7, 146.2, 138.2, 135.5, 134.7, 132.3, 128.6, 126.0, 125.3, 125.1, 118.0, 116.7, 112.9, 79.1, 21.350. Elemental analysis: Anal. Calcd. for C22H18 INO5 S: C, 49.31; H, 3.36; N, 2.61; S, 5.98. Found: C, 47.16; H, 3.59; N, 2.94; S, 9.63.

Preparation of 3-phenyliodoniocoumarin-4-imide (T3)

A solution containing 2% aqueous sodium hydroxide (8 ml, 4 mM) was introduced to 4-A-3-PIC T (1.07 g, 2 mM). Following thirty minutes of stirring at room temperature, the resulting yellow solid was filtered (Scheme 3), successively washed with water and diethyl ether, and then dried under vacuum, yielding 0.668 g (92%) of the compound 3-phenyliodoniocoumarin-4-imide (3-PIC-4-I), mp 93–95 °C; IR (nujol): Vmax 3450, 1620, 1595 cm-1; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.03 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2 H), 7.83 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2 H), 7.49 (dd, J = 13.4, 5.7 Hz, 1 H), 7.39 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1 H), 7.21–7.15 (m, 1 H), 6.88 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2 H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 153.2, 152.8, 133.3, 133.2, 132.6, 131.8, 131.6, 131.2, 131.1, 129.3, 125.6, 123.9, 122.1, 117.3. Elemental analysis: Anal. Calcd. for C15H10INO2: C, 49.56; H, 2.75; N, 3.85. Found: C, 48.17; H, 2.57; N, 3.93.

Preparation of 3-iodo-4-phenylaminocoumarin (T4)

A reflux was performed on a suspension of 4-A-3-PIC (0.363 g, 1 mM) in acetonitrile (15 mL) for three hours (Scheme 4). The resulting solution was evaporated to dryness, and the remaining crude solid was recrystallized from ethanol, yielding 0.29 g (80%) of the compound 3-iodo-4-phenylaminocoumarin (3-I-4-PAC), mp 181–182 °C; IR (nujol): Vmax 3300, 1675, 1585 cm-1; l H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.29 (m, 1 H), 8.75–8.96 (1 H), 8.17 (dd, J = 37.8, 8.0 Hz, 2 H), 7.62–7.57 (m, 2 H), 7.46–7.19 (m, 1 H), 7.03-7.00 (m, 2 H), 5.26 (s, 1 H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 159.8, 154.4, 153.2, 141.7, 132.9, 130.1, 129.4, 125.6, 124.9, 123.7, 122.4, 117.3, 116.5, 72.8. Elemental analysis: Anal. Calcd. for C15H10INO2: C, 49.56; H, 2.75; N, 3.85. Found: C, 48.32; H, 2.61; N, 4.25.

Preparation of 4-phenylaminocoumarin (T5)

A catalytic amount of PdCl2(PPh3)2 (0.035 g, 0.05 mM) was added to a solution of 3-I-4-PAC (0.363 g, 1 mM) in tetrahydrofuran (THF) (10 mL) and triethylamine (Et3N) (5 mL), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature until the disappearance of 3-I-4-PAC (3 h, monitored by TLC, silica-coated plates, hexane-ethyl acetate 2:1) (Scheme 5). After removal of the solvent, the residue was chromatographed on a column (silica gel, hexane-ethyl acetate 2:1) to yield 4-phenylaminocoumarin (4-PAC) (0.178 g, 75%); mp 266–267 °C; IR (nujol): Vmax 3280, 1655, 1610, 1585 cm-1; 1 H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.46 (d, J = 36.6 Hz, 1 H), 8.37 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.94 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2 H), 7.77 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 2 H), 7.60–7.50 (m, 2 H), 5.55 (s, 1 H), 5.39 (s, 1 H, NH).

Preparation of 4-diphenylamino-3-iodocoumarin (T6)

(Diacetoxy) iodobenzene (0.966 g, 3 mM) was added to a stirring suspension of 4-PAC (0.237 g, 1 mM) in dichloromethane (15 mL). After one day at room temperature, the resulting solution was evaporated. The residue was chromatographed on a column (silica gel, hexane-ethyl acetate 10:1). After a small amount of iodobenzene, 4-diphenylamino-3-iodocoumarin (4-DPA-3-IC) (0.307 g, 70%) was eluted and recrystallized from ethanol as yellow crystals (Scheme 6), mp 247–248 °C; IR (nujol): Vmax 1695, 1580 cm-1; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.94 (dd, J = 7.6, 1.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.57–7.55 (m, 1 H), 7.34 (m, 2 H), 7.28–7.26 (m, 4 H), 7.25 (d, J = 3.1 Hz, 2 H), 5.17 (m, 4 H).

ADME and toxicity studies

The pharmacokinetic (Adsorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion-ADME) and toxicity profiles of synthesized compounds were analyzed using Swiss ADME and PreADMET-open web tools38.

In silico target prediction and molecular docking studies

The PDB structures of various bacterial, fungal, and viral targets were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (RCSB) (Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics). Docking studies were performed using AutoDock Vina 1.5.6, following standard procedures54.

Antibacterial activity

The target compounds were assessed for antibacterial activities using the disk diffusion technique55 on Gram-positive bacterial species (Staphylococcus aureus MTCC 96 and Bacillus substilis MTCC 441) and Gram-negative bacterial species (Pseudomonas aeruginosa MTCC 741, Salmonella typhimurium MTCC 3224, Escherichia coli MTCC 443, Proteus mirabilis MTCC 425, Klebsiella pneumoniae MTCC 109, and Acinetobacter baumannii MTCC 9829). Stock solutions with a 100 µg/mL concentration for synthesized target compounds were made by dissolving the compounds in DMSO. After 18 h of incubation at 37 °C, the ZOI was measured in mm. To elucidate the influence of DMSO on biological screening, a separate study was employed using 99.5% DMSO as the control. For comparison, different commercially available antibiotic discs such as Novobiocin, Oxacillin, Methicillin, Ampicillin, and Gentamycin were used as standard positive controls for the antibacterial study. Each experiment was performed in triplicate. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) for each synthetic derivative against each test organism were calculated using the broth microdilution-based method outlined in the literature according to the CLSI (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute) standards and guidelines56.

Antifungal activity

The antifungal activity of the target compounds (100 µg/mL) in DMSO was tested using the disc diffusion method57 against different plant fungal pathogens such as Aspergillus niger MTCC 281, Fusarium oxysporum MTCC 284, Fusarium solani MTCC 350, Penicillium chrysogenum MTCC 161, and Candida albicans MTCC 183. The study used 5-Flurocytosine (5-FC) as the positive control and the disc containing DMSO as the negative control. Each experiment was performed in triplicate. The fungal growth in the drug-treated Potato dextrose Agar (PDA) plates was monitored, and the average fungal growth diameter readings were taken on the 3, 5, and 7 days, respectively. The percentage diameter inhibition growth (PDIG) was measured with the increase in diameter in the control plate using Eq. 1 below.

D1 is the diameter growth (in mm) of the pathogen in the control plate, and D2 is the diameter growth (in mm) of the pathogen in the test plate.

Antiviral activity

The cytotoxicity of the synthesized compounds (T1-T6) was evaluated using the MTT assay on BHK-21 cell lines to determine the Maximum Non-Toxic Dose (MNTD). An in vitro cytopathic effect (CPE) reduction assay5 was then performed in triplicate using Dengue virus type-2 (DENV2). A virus stock with a Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) of 0.02 was prepared in DMEM containing 2% FBS (Fetal Bovine Serum). BHK-21 cells were seeded into a 24-well plate at a density of 1 × 10⁵ cells/well, and the preformed monolayer was inoculated with serially diluted DENV2 for 1 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO₂. Control wells were included for cells, viruses, and compounds, with castanospermine as a positive control. The synthesized compounds were diluted in DMEM (2% FBS) to various concentrations within their MNTD range. At 1-hour post-infection, the cells were treated with the compounds and incubated under the same conditions. The 24-well plate was subsequently observed using a phase-contrast microscope to assess the ability of the compounds to prevent CPE.

Antioxidant activity

The antioxidant activities of target compounds were screened using the DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picryl-hydrazine-hydrate) method58. DPPH (4 mg/100 ml) in methanol was prepared, and 1 mL of this solution was mixed with 1 to 500 µg/ml of coumarin derivatives (Abs) and the standard ascorbic acid in methanol. Controller tubes were prepared using 1 ml DPPH and methanol (Abc). The same volume of methanol alone was kept as blank. All the samples were incubated for 20–30 min at 37 °C in a water bath. Then, the decrease in absorbance at 515 nm was measured. The experiment was carried out in triplicate. Radical scavenging activity was calculated using the following formula (2):

Cell culture

Immortalized human keratinocyte HaCaT cell lines were purchased from the National Center for Cell Science (Pune), India. The cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% antibiotic antimycotic solution. Cell cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The culture medium was changed every two days, and cells were trypsinized for 10 min and resuspended in the same medium when the culture achieved 80% confluence.

Cytotoxicity assessment using the MTT assay

The impact of target compounds on cytotoxicity in the HaCaT cell line was measured through MTT assay at varying concentrations59. Briefly, HaCaT cells were harvested, counted, and seeded at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well in a 96-well plate for 24 h. Subsequently, the cells were exposed to various sample concentrations of 1 to 100 µg/mL and incubated for 48 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) was used as the positive control, and untreated cells (in a separate well) were used as the negative control to assess baseline cell viability. Following this, 20 µL of 5 mg/mL MTT (Merck, USA) reagent was introduced to each well and incubated for 4 hours. The solution was then replaced, and 100 µL of lysis buffer containing 20% Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in 50% Dimethylformamide (DMF) was added, followed by a 2-hour incubation. Finally, the plate was read at 570 nm using a microtiter plate reader, and the results were analyzed as the percentage proliferation of the treated samples.

In vitro scratch wound healing studies

The cell migration of HaCaT cells in response to synthetic coumarin compounds was evaluated using a standard scratch wound healing assay protocol60. The cells were cultured in 24-well plates with a final concentration of 1 × 104 cells per well and allowed to reach confluence. Subsequently, the culture medium was removed, and controlled scratches were made using micropipette tips at a 90° angle to confine the scratch width. The scratched areas were then replenished with 1 to 2mL of media according to the following conditions: (i) fresh culture medium alone (cell control); (ii) synthetic coumarin compounds at concentrations of 10 µg/mL; (iii) 0.1% DMSO (negative control); and (iv) cells treated with 5-fluorouracil at two concentrations, such as IC50 and < IC50. The cells were incubated for 0 to 48 h, and the wound area was documented and examined using an inverted microscope (AXIOCAM 105 color) at 40x and 100x magnification.

Statistical analysis

All experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Results were analyzed for significance by one-way ANOVA using SPSS software version 16.0.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript and its supplementary information files. Any other datasets such as raw data or specific analyses not directly included in the publication, are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Tanwar, J., Das, S., Fatima, Z. & Hameed, S. Multidrug resistance: An emerging crisis. Interdiscipl. Perspect. Infect. Dis. 2014 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/541340

Balendres, M. A. O. Plant diseases caused by fungi in the Philippines. Mycol. Trop. Updat Philipp Fungi. 163–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-99489-7.00014-7 (2022).

Xu, L., Yu, J., Jin, L., Pan, L. & Design synthesis, and antifungal activity of 4-Amino coumarin based derivatives. Molecules 27 (2022).

Gogoi, D., Baruah, P. J. & Narain, K. Immunopathology of emerging and re-emerging viral infections: An updated overview. Acta Virol. 68, 1–7 (2024).

Muhamad, M., Kee, L. Y., Rahman, N. A. & Yusof, R. Antiviral actions of flavanoid-derived compounds on dengue virus type-2. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 6, 294–302 (2010).

Sareena, C. & Vasu, S. T. Identification of 4-diphenylamino 3-iodo coumarin as a potent inhibitor of DNA gyrase B of S. aureus. Microb. Pathog. 147, 104387 (2020).

Nagamallu, R., Srinivasan, B., Ningappa, M. B. & Kariyappa, A. K. Synthesis of novel coumarin appended bis(formylpyrazole) derivatives: studies on their antimicrobial and antioxidant activities. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 26, 690–694 (2016).

Yu, H., Hou, Z., Yang, X., Mou, Y. & Guo, C. Design, synthesis, and mechanism of dihydroartemisinin-coumarin hybrids as potential anti-neuroinflammatory agents. Molecules 24, (2019).

Mishra, S., Pandey, A. & Manvati, S. Coumarin: An emerging antiviral agent. Heliyon 6, e03217 (2020).

Elias, R. et al. Antifungal activity, mode of action variability, and subcellular distribution of coumarin-based antifungal Azoles. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 179, 779–790 (2019).

Hu, Y. et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 3-arylcoumarin derivatives as potential anti-diabetic agents. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 34, 15–30 (2019).

Kostova, I. et al. Coumarins as antioxidants. Curr. Med. Chem. 18, 3929–3951 (2012).

Yadav, A. K., Shrestha, M., Yadav, P. N. & R. & Anticancer mechanism of coumarin-based derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 267, 116179 (2024).

Song, M. X. & Deng, X. Q. Recent developments on Triazole nucleus in anticonvulsant compounds: A review. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 33, 453–478 (2018).

Greaves, M. Pharmacogenetics in the management of coumarin anticoagulant therapy: The way forward or an expensive diversion? PLoS Med. 2, 0944–0945 (2005).

Mauldin, K., Alzheimer’, S. & Disease Encycl Hum. Mem. [3 Vol 1–3, 54–62 (2013).

Supuran, C. T. Coumarin carbonic anhydrase inhibitors from natural sources. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 35, 1462–1470 (2020).

Singh, R. K., Devi, S. & Prasad, D. N. Synthesis, physicochemical and biological evaluation of 2-amino-5-chlorobenzophenone derivatives as potent skeletal muscle relaxants. Arab. J. Chem. 8, 307–312 (2015).

Singh, R. K. Key heterocyclic cores for smart anticancer drug–design part I. Bentham Sci. Publishers. https://doi.org/10.2174/97898150400741220101 (2022).

Xie, S. S. et al. Multi-target tacrine-coumarin hybrids: Cholinesterase and monoamine oxidase B Inhibition properties against Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 95, 153–165 (2015).

Lan, J. S. et al. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of novel coumarin-N-benzyl pyridinium hybrids as multi-target agents for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 139, 48–59 (2017).

Roussaki, M., Kontogiorgis, C. A., Hadjipavlou-Litina, D., Hamilakis, S. & Detsi, A. A novel synthesis of 3-aryl coumarins and evaluation of their antioxidant and Lipoxygenase inhibitory activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 20, 3889–3892 (2010).

Kostova, I. Coumarins as inhibitors of HIV reverse transcriptase. Curr. HIV Res. 4, 347–363 (2006).

Matos, M. J. et al. Synthesis and evaluation of 6-methyl-3-phenylcoumarins as potent and selective MAO-B inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 19, 5053–5055 (2009).

Ostrov, D. A. et al. Discovery of novel DNA gyrase inhibitors by high-throughput virtual screening. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51, 3688–3698 (2007).

Carneiro, L. S. A. et al. Synthesis of 3-aryl-4-(N-aryl)aminocoumarins via photoredox arylation and the evaluation of their biological activity. Bioorg. Chem. 114, (2021).

Soni, R. & Soman, S. S. Design and synthesis of aminocoumarin derivatives as DPP-IV inhibitors and anticancer agents. Bioorg. Chem. 79, 277–284 (2018).

Maria, T. & Kostova, I. Coumarin derivatives and oxidative stress. Int. J. Pharmacol. 1, 29–32 (2004). https://doi.org/10.3923/ijp.2005.29.32

Morguette, A. E. B. et al. The antibacterial and wound healing properties of natural products: A review on plant species with therapeutic potential against Staphylococcus aureus wound infections. Plants 12, (2023).

Daneman, R. & Prat, A. The blood-brain barrier. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 7(1), a0204 (2015).

Fogel, D. B. Factors associated with clinical trials that fail and opportunities for improving the likelihood of success: A review. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 11, 156–164 (2018).

Stamboliyska, B. et al. Experimental and theoretical investigation of the structure and nucleophilic properties of 4-aminocoumarin. Arkivoc 2010, 62–76 (2010).

Janusz Grabowski, S. Review commentary hydrogen bonding strength-measures based on geometric and topological parameters. J. Phys. Org. Chem. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 17, 18–31 (2004).

Parr, R. G. & Yang, W. Density functional approach to the frontier-electron theory of chemical reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 106, 4049–4050 (1984).

Milanović, Ž. B. et al. Synthesis and comprehensive spectroscopic (X-ray, NMR, FTIR, UV–Vis), quantum chemical and molecular Docking investigation of 3-acetyl-4–hydroxy–2-oxo-2H-chromen-7-yl acetate. J. Mol. Struct. 1225, (2021).

Nandiyanto, A. B. D., Oktiani, R. & Ragadhita, R. How to read and interpret Ftir spectroscope of organic material. Indones J. Sci. Technol. 4, 97–118 (2019).

Rajan, V. K. & Muraleedharan, K. A computational investigation on the structure, global parameters and antioxidant capacity of a polyphenol, Gallic acid. Food Chem. 220, 93–99 (2017).

Daina, A., Michielin, O., Zoete, V. & SwissADME A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–13 (2017).

Arnott, J. A. & Planey, S. L. The influence of lipophilicity in drug discovery and design. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 7, 863–875 (2012).

Savjani, K. T., Gajjar, A. K. & Savjani, J. K. Drug solubility: Importance and enhancement techniques. ISRN Pharm. (2012). (2012).

Elmeliegy, M., Vourvahis, · Manoli, C., Guo, ·, Wang, D. D. & Com, M. E. Effect of P-glycoprotein (P-gp) inducers on exposure of P-gp substrates: Review of clinical drug-drug interaction studies. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 59, 699–714 (2020).

Finch, A. & Pillans, P. P-glycoprotein and its role in drug-drug interactions. Aust Prescr. 37, 137–139 (2014).

Montanari, F. & Ecker, G. F. Prediction of drug-ABC-transporter interaction—recent advances and future challenges. Adv. Drug Deliv Rev. 86, 17–26 (2015).

Lipinski, C. A. Lead- and drug-like compounds: The rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 1, 337–341 (2004).

Awais Attique, S. et al. A molecular Docking approach to evaluate the Pharmacological properties of natural and synthetic treatment candidates for use against hypertension. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Heal Artic. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16060923 (2019).

Pires, D. E. V., Blundell, T. L. & Ascher, D. B. & 1ga, U. K. pkCSM: Predicting small-molecule pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties using graph-based signatures. (2015). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00104

Vidler, L. R., Watson, I. A., Margolis, B. J., Cummins, D. J. & Brunavs, M. Investigating the behavior of published PAINS alerts using a pharmaceutical company data set. ACSMed Chem. Lett. 7, 792–796 (2018).

Ali, D., Alarifi, S., Chidambaram, S. K., Radhakrishnan, S. K. & Akbar, I. Antimicrobial activity of novel 5-benzylidene-3-(3-phenylallylideneamino)imidazolidine-2,4-dione derivatives causing clinical pathogens: Synthesis and molecular docking studies. J. Infect. Public. Health. 13, 1951–1960 (2020).

Liang, C. C., Park, A. Y. & Guan, J. L. In vitro scratch assay: A convenient and inexpensive method for analysis of cell migration in vitro. Nat. Protoc. 2, 329–333 (2007).

Papoutsis, I., Spyroudis, S. & Varvoglis, A. Phenyliodonium derivatives from 4-aminocoumarin and their reactivity. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 33, 579–581 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1002/jhet.5570330308

Ivanov, I. C., Angelova, V. T., Vassilev, N., Tiritiris, I. & Iliev, B. Synthesis of 4-Aminocoumarin derivatives with N-Substitutents containing hydroxy or amino groups. Z. fur Naturforsch - Sect. B J. Chem. Sci. 68, 1031–1040 (2013).

Farshid Hassanzadeh and Elham Jafari. Cyclic imide derivatives: As promising scaffold for the synthesis of antimicrobial agents. 23: 53 (2018). https://doi.org/10.4103/jrms.JRMS_539_17

Hua, C. et al. A novel turn off fluorescent sensor for Fe(III) and pH environment based on coumarin derivatives: the fluorescence characteristics and theoretical study. Tetrahedron 72, 8365–8372 (2016).

Forli, S. et al. Computational protein-ligand Docking and virtual drug screening with the AutoDock suite. 11, 905–919 (2016).

Ahmad, R. et al. Antioxidant, radical-scavenging, anti-inflammatory, cytotoxic and antibacterial activities of methanolic extracts of some Hedyotis species. Life Sci. 76, 1953–1964 (2005).

Melvin, P. & Weinstein, J. S. L. I. The clinical and laboratory standards Institute subcommittee on antimicrobial susceptibility testing: Background, organization, functions, and processes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 58, e01864–e01819 (2020).

Johnson, E. M. & Cavling-Arendrup, M. Susceptibility test methods: Yeasts and filamentous fungi. Man. Clin. Microbiol. 2255–2281. https://doi.org/10.1128/9781555817381.ch131 (2015).

Dudonné, S., Vitrac, X., Coutière, P., Woillez, M. & Mérillon, J. M. Comparative study of antioxidant properties and total phenolic content of 30 plant extracts of industrial interest using DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, SOD, and ORAC assays. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57, 1768–1774 (2009).

Tolosa, L., Donato, M. T. & Gómez-Lechón, M. J. General cytotoxicity assessment by means of the MTT assay. In Protocols in in Vitro Hepatocyte Research (eds Vinken, M. & Rogiers, V.) 333–348 (Springer, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-2074-7_26.

Martinotti, S. & Ranzato, E. Scratch wound healing assay. Methods Mol. Biol. 2109, 225–229 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We want to express our sincere gratitude to Dr. E. Sreekumar, Director, Institute of Advanced Virology, Kerala, for his invaluable support and guidance in conducting the antiviral studies presented in this research. We also extend our heartfelt thanks to the Centre for Advances in Molecular Biology, University of Calicut, for providing the lab facilities for conducting the cell culture studies. We also acknowledge all the financial support from the Council of Scientific & Industrial Research (CSIR), India- Human Resource Development Group (HRDG) in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Z., S.T.M., K.V.M., S.J., and STV designed the experiments; S.Z. synthesized the compounds, performed all in vitro/in silico experiments, wrote and edited the manuscript, S.T.M. performed cell culture works and interpretation of results, S.J. contributed to antiviral studies and data analysis, K.VM., S.T.V., and S.J. supervised all experiments, analyzed data, and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zachariah, S., M, S.T., Vadakkadath Meethal, K. et al. Synthesis, biological evaluation, pharmacological profiling, and molecular docking studies of 4-Aminocoumarin based phenyliodonium derivatives as potent therapeutic agents. Sci Rep 15, 21762 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95078-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95078-8