Abstract

Existing studies have focused on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after surgery in patients with knee osteoarthritis (KOA), whereas PTSD in non-operated elderly KOA patients has not been adequately studied. The aim was to assess the current status of PTSD and its influencing factors among non-surgical elderly KOA patients. From October to November 2021, a cross-sectional study was conducted among 320 consecutive patients aged ≥ 65 years with radiologically confirmed KOA and no history of knee surgery or psychiatric disorders, recruited from three community hospitals in Changsha, Hunan Province. A total of 314 participants completed validated assessments for PTSD (PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version), pain (Numerical Rating Scale), anxiety (Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale), depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-9), and social support (Social Support Rating Scale). Data were analyzed using non-parametric tests and Spearman correlation. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was performed with Amos 24.0, employing maximum likelihood estimation and 1000 bootstrap samples to test mediation effects. Among 314 analyzed participants (mean age 72.91 ± 6.384 years; 60.80% female and 39.20% males), PTSD prevalence was 18.20%. Significantly higher PTSD risk was associated with low education levels (Z=−2.398, P = 0.016), low salaries (H = −2.398, P = 0.005), unemployed patients (H = 10.030, P = 0.007), no exercise (H = 9.328, P = 0.025), smoking (Z = −2.504, P = 0.012) and no leisure activities (Z=−2.074, P = 0.038). Structural equation modeling revealed a direct effect of depression on PTSD with the path coefficient of 0.701 (95% CI 0.518–0.879, P = 0.001) and an indirect effect of pain on PTSD through social support with the path coefficient of −0.014 (95% CI −0.049 to −0.001, P = 0.035 < 0.05). Non-surgical elderly patients with knee osteoarthritis exhibit clinically significant post-traumatic stress disorder rates (18.20%), primarily driven by depression and mediated through pain-social support pathways. These findings underscore the need for integrated biopsychosocial interventions targeting pain management, mental health screening, and social support enhancement in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoarthritis of knee (KOA) is a chronic and disabling disease characterized by characterized by persistent, recurring pain and severe damage to the joints, accompanied by biomechanical disorders, functional decline, and disability1. Older adults are at high risk for the onset of KOA, with close to one-third of those aged 65 years and older suffering from KOA2. It is projected that the number of KOA cases will increase by 74.9% globally by 20503. It ranges from intermittent pain in the early stages to persistent vague pain accompanied by intense intermittent sharp pain in the late stages2. Severe pain is the hallmark symptom of KOA and has a profound psychological impact on the patient4,5. It is now well established that chronic pain-induced anxiety, depression, and pain catastrophizing in patients with KOA6,7, whether chronic pain in KOA induces post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has not been proven.

PTSD is a psychiatric disorder that may occur in people who have experienced or witnessed a traumatic event, a series of events, or an environment8. KOA patients suffer from persistent joint pain for a long time and have been in an environment of chronic pain assault, which is a kind of trauma from physical and psychological. In the long run, some patients fear pain and become hypervigilant to pain9. A review of the literature has revealed a large number of shared brain regions between pain and fear memories, a typical feature of PTSD, confirming the interaction between pain and PTSD10,11. Clinical data have shown that the prevalence of PTSD is as high as 50% in patients with pain, which is much higher than in the general population (6% in males and 12% in females)12. It is evident that severe pain in patients with KOA may induce the risk of PTSD.

Despite advances in the treatment of KOA, the psychological impact of chronic pain, particularly PTSD, remains understudied. Previous studies have focused on PTSD in post-surgical KOA patients; for example, CREMEANS-SMITH et al.13 followed 110 postoperative KOA patients and found that 20% (22) developed PTSD symptoms 3 months after surgery. These studies suggest that severe pain13, fractures14, psychological complications (e.g., anxiety, depression)15,16, and low social support17 are common risk factors for PTSD in patients undergoing KOA surgery. However, studies on the incidence of PTSD, its mechanisms, and its influencing factors in non-surgical KOA patients are very limited, which constitutes an important gap in current research.

Non-surgical KOA patients also face chronic pain, functional limitations, and inadequate social support, which may be closely related to the occurrence of PTSD in non-surgical patients18. In China, the social dilemma of older adults facing retirement is more embarrassing compared to developed countries19. Older adults have reduced wages after retirement, which may increase their risk of developing PTSD due to external (e.g., social isolation) and internal (e.g., chronic pain, anxiety) stressors20. Therefore, understanding the relationship between social support in pain, anxiety, depression, and PTSD has important clinical implications for researchers, clinicians, and patients.

We hypothesized that: i) the direct effect of chronic pain level, anxiety, and depression on PTSD in elderly KOA patients with chronic pain; ii) the mediating role of social support in pain level and PTSD, anxiety, and PTSD, and depression and PTSD. Structural equation modeling was proposed to confirm the above hypotheses. The aim of this study was to provide a reference point for early identification and intervention of PTSD in KOA patients by examining the prevalence of PTSD and its modifiable risk factors in elderly KOA patients.

Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study conducted in China to understand the status of PTSD and its influencing factors in elderly KOA patients. We used the STROBE reporting checklist to guide study reporting. The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Clinical Medical Ethics Committee of Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (E2020133).

Study settings and participants

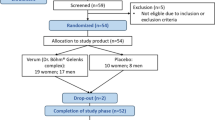

From October to November 2021, 320 elderly patients with osteoarthritis of the knee who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were selected from three community hospitals in Changsha, Hunan Province, China. Inclusion criteria: (1) age ≥ 65 years; (2) The patients were diagnosed with KOA for three months or more and had not undergone knee arthroplasty. (3) Satisfy KOA diagnostic criteria, which refer to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11, code: FA01)21, 2018 edition of the Bone and Joint Diagnostic and Therapeutic Guidelines22: (i) the presence of recurrent knee pain in the last month; (ii) X-ray (standing or weight-bearing position) showed narrowing of the joint space, osteosclerosis and cystic degeneration of the subchondral bone, and the formation of bone cumbersomening on the edge of the joint; (iii) age ≥ 50 years old; (iv) morning stiffness ≤ 30 min; (v) bone friction sound (sensation) during activity (KOA can be diagnosed by fulfilling the diagnostic criteria (i) + (any 2 of (ii), (iii), (iv), (v); the above diagnosis was made by two orthopedic surgeons with more than 10 years of experience in the hospital and recorded in the medical record system; (4) voluntary participation in the study. Exclusion criteria: (1) patients who had undergone knee arthroplasty; (2) patients with psychiatric disorders and cognitive communication disorders; (3) patients taking psychotropic medications; (4) patients with comorbidities of other psychiatric disorders.

Firstly, all the community hospitals in Changsha city were numbered and then a random number generator was used to generate random numbers and three of the community hospitals were selected from so community hospitals as the study sites. The researcher screened all the patients who met the criteria from the database of the community hospitals as a total sample and then used a random number generator to extract 320 patients from the total sample as the study population. Strict randomization method was followed during the sampling process to ensure the representativeness of the sample.

Sample size

The cross-sectional study formula was used to calculate the sample size23.

The literature shows that the detection rate of PTSD in orthopedic patients is 15–40%13,17, so p = 40% , q = 1-p = 0.6, d = 0.15 and Zα2 = 1.96 were set in this study. Considering the 20% sample invalidity rate, the final sample size was at least 307. In this study, 320 study participants were recruited, and after excluding incomplete questionnaires, 314 cases were finally included.

Measures

General information questionnaire

The researchers designed the questionnaire, including gender, age, education level, type of occupation before retirement, frequency of physical exercise, and whether there are any abnormal symptoms in the knee joint.

Post-traumatic stress disorder status

The code for PTSD in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) was 6B40. The civilian version of the Post-traumatic Stress Checklist (PCL-C) was used to assess PTSD symptoms. It was developed by the PTSD Research Center in the U.S. It consisted of three major symptom clusters: reexperiencing of the trauma (5 entries), avoidance numbing (7 entries), and increased alertness (5 entries)24. A Likert 5-point scale was used, with a total score of 17–85, Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.88–0.9424. A score of 38 was used as the demarcation criterion for PTSD positivity. Symptom scores of ≥ 3 for each entry were considered positive; among the three symptom clusters, those with ≥ 1 positive re-experiencing symptom (e.g., in the re-experiencing symptom cluster, re-experiencing symptoms were judged positive if 1 or more entries scored ≥ 3), ≥ 3 positive avoidance numbing symptoms, and ≥ 2 positive increased alertness symptoms were adjudged positive for that symptom cluster.24.

Pain

Pain level was assessed by the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), a tool proposed by JOOS et al. in 199125. It consists of 11 numbers from 0 to 10, which visually and accurately assesses the pain level of the study population from small to large. Applying the scale has been shown to have high reliability and validity, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.8926.

Anxiety

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) was used to assess the anxiety status of the study participants27. A total of 7 entries were scored on a 4-point Likert scale, with higher scores being associated with higher levels of anxiety. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.898, and the retest reliability coefficient was 0.85628.

Depression

The Patient Health Questionnaire depression module (PHQ-9) was used to assess the depressive symptoms of the study subjects. It was developed by Kroenke et al.29 and was scored on a Likert 4-point scale; the higher the score, the higher the level of depression. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.832530.

Social support

The Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS) assessed the study participants’ social support level. Prof. Xiao Shuiyuan developed the scale with ten items in 3 dimensions31. The total score ranged from 12 to 66, with higher scores indicating higher levels of social support received by the individuals. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the scales were 0.896, respectively32.

Data collection and bias

Data collection took place between October and November 2021 to ensure that patients included in the study had a confirmed diagnosis of KOA of three months and above and had not been treated with knee replacement surgery. Patients were excluded from the study if they had undergone knee replacement surgery. The study settings were three community hospital where patients mostly resided nearby and were geographically concentrated, so the researcher recruited patients directly through face-to-face interactions. During the questionnaire process, the researcher explained in detail the purpose of the study, the methodology, and the requirements for completion to the subjects, and explicit consent was obtained. To ensure that patients completed the questionnaires independently, all questionnaires used standardized prompt items and were filled out in a consenting environment to avoid privacy interference. For elderly people who were unable to complete the questionnaire independently, the research team arranged for experienced investigators to assist in completion. All questionnaires were distributed and collected on the spot, and the investigators were responsible for checking the completeness and accuracy of the questionnaires.

Data analysis

Questionnaires with missing data were excluded to ensure data quality. For the descriptive analysis of the data, mean, standard deviation, frequency (n), and composition ratio (%) were used for normal distribution, and M (P25, P75) was used for non-normal distribution. Comparisons of differences between groups were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test (between two groups) and the Kruskal–Wallis H test (three or more groups). Spearman’s correlation was used to analyze whether there was a correlation between PTSD and the variables. Finally, structural equation modeling was constructed to analyze the effects of pain, anxiety, and depression on PTSD and the mediating role of social support in the middle, and the bootstrap method was applied to verify the mediating effect. After the initial establishment of the model, we calculated the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < 0.08)33, goodness of fit index (GFI ≥ 0.90)33, comparative fit index (CFI ≥ 0.90)33, adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI ≥ 0.80)34, χ2df < 335 and normed fit index (NFI ≥ 0.90)33, based on Hoyle and Benlter’s studies, to fit the structural equation model by were evaluated and the model was adjusted. SPSS 27.0 and AMOS 24.0 software were used to analyze the data, and a P value of < 0.05 was considered a statistically significant difference. Bootstrap CI was set at 95%, and the bootstrap sample size was 1,000. a significant mediation effect was indicated if the 95% CI interval did not contain zero.

Results

Current status of post-traumatic stress disorder in elderly patients with knee osteoarthritis

320 questionnaires were collected, of which 314 were valid, with a valid recovery rate of 98.13%.The mean PCL-C score of the 314 study participants was 28.42 ± 11.17. Based on a total score of ≥ 38, 57 (18.20%) tested positive for PTSD. Among the three symptom clusters, 81 cases (25.80%) were positively detected in the repeated experience symptom cluster, 44 cases (14.00%) were positively detected in the avoidance numbing symptom cluster, and 69 cases (21.90%) were positively detected in the increased alertness symptom cluster. PCL-C scores and positive detections for each symptom group are shown in Table 1.

Analysis of different characteristics and PCL-C scores of the study population

Of the 314 participants, the youngest was 65 years old, and the oldest was 93 years old, with a mean age of 72.91 ± 6.384 years. 123 (39.2%) were males, and 191 (60.8%) were females.

The results of the univariate analysis showed that different educational levels and weekly exercise frequencies affected the PCL-C total score (Z = − 2.398, P = 0.016; H = 9.328, P = 0.025), the avoidance numbing symptom cluster (Z = − 2.554, P = 0.011; H = 8.738, P = 0.033), and the increased alertness symptom cluster (Z = − 2.147, P = 0.032; H = 13.195, P = 0.004) scores of KOA patients. Type of occupation before retirement, and salary level affected the PCL-C total score (H = 10.030, P = 0.007; H = 15.051, P = 0.005), the repeated patient experiences symptom cluster (H = 8.020, P = 0.018; H = 15.722, P = 0.003), the avoidance numbing symptom cluster (H = 10.920, P = 0.004; H = 13.570, P = 0.009)and the increased alertness symptom cluster (H = 9.080, P = 0.011; H = 11.701, P = 0.020) scores of KOA patients. Patients who smoked had higher PCL-C scores (Z = − 2.504, P = 0.012). The presence of stiffness in the patient’s knee affected the score for the symptom cluster of increased alertness (Z = − 2.426, P = 0.015), and the presence of friction in the knee affected the score for the symptom cluster of repeated patient experiences (Z = − 2.258, P = 0.024). A comparison of the different characteristics of the study population with the total PCL-C score is shown in Table 2.

Correlation analysis of PTSD symptoms with pain, anxiety, depression, and social support among participants

The pain score of 314 study participants was 3.18 ± 2.23; anxiety and depression scores were 4.18 ± 4.32 and 4.72 ± 4.39; and the social support score was 39.51 ± 8.83. Before constructing the structural equation model, we conducted a correlation analysis of the relationship between pain, anxiety, depression, social support and PTSD. The results showed that anxiety, depression, and pain were significantly and positively correlated with PTSD (r = 0.679, r = 0.736, r = 0.224, all P < 0.01), respectively, indicating that the higher the level of anxiety and depression, the higher the intensity of pain, and the more severe the symptoms of PTSD. Social support and PTSD showed a significant negative correlation (r = − 0.089, P < 0.01), indicating that the lower the social support, the more severe the PTSD symptoms. The specific results are shown in Table 3.

Model fit index and path mediation analysis of PTSD models in elderly KOA patients

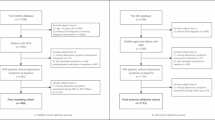

The results of the correlation analysis supported our research hypothesis that psychological factors (anxiety, depression) and physiological factors (pain) are significant predictors of PTSD, while social support may play a protective role against PTSD by alleviating psychological stress. An initial structural model was developed using pain, anxiety, and depression as exogenous variables, social support as a mediating variable, and PTSD as an endogenous variable. The fitting results of the initial model: chi-square/degrees of freedom (χ2/df) = 3.201, root mean square of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.084, goodness of fit index (GFI) = 0.779, adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI) = 0.737, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.841, the fit index of the initial model has not yet reached the fit criterion. Therefore, the model was corrected based on the correction index, and only one value was corrected at a time. After correction and reanalysis, the results showed that each index met reached the acceptable range of the fit index (Table 4), indicating that the data of the corrected model fit better.

The final structural equation model of PTSD in elderly KOA patients by correction was shown in Fig. 1. Correlation analysis showed that PTSD with pain (r = 0.024, P < 0.01), anxiety (r = 0.679, P < 0.01), social support (r = − 0.089, P < 0.01) and depression (r = 0.736, P < 0.01) were significantly correlated. But anxiety, pain, and PTSD were not significantly correlated in the structural equation model except for depression, suggesting that there was an indirect link between anxiety, pain, and PTSD, in which social support played a fully mediating role. The link between depression and PTSD was direct (95% CI 0.518–0.879, P = 0.001), and social support played a partial mediating role between depression and PTSD (95% CI: -0.049- -0.001, P = 0.035 < 0.05). The influence paths and effect relationships of the variables in the model were shown in Table 5.

Discussion

In this study of 314 elderly KOA patients, the prevalence of PTSD was 18.20%. Structural equation modeling showed that depression directly affected PTSD and pain mediated significantly on PTSD through social support.

Current status of post-traumatic stress disorder in elderly patients with knee osteoarthritis

A total of 314 elderly KOA patients were investigated in this study, and the incidence of PTSD (PCL-C scores > 38) was 18.20%. This rate is lower than the PTSD incidence of 20% to 40% in orthopedic patients undergoing surgery in previous studies13,17, but still suggests that our KOA patients face non-negligible mental health risks. Our findings remain revealing because prior studies have focused on orthopedic patients undergoing surgery. Compared with orthopedic patients undergoing surgery, elderly KOA patients do not experience direct physical trauma from surgical procedures, but long-term knee pain and dysfunction are equally physically and psychologically traumatizing37. Stressors associated with KOA involve pain, negative psychology, life stressors, and the experience of illness caused by recurrent symptoms, such as disability, financial burden, and social stigma4,38. There are also multifaceted factors, such as uncertainty about the effectiveness of treatment and concerns about future declines in quality of life514.

In this study, among the three significant syndromes of stress disorder, the positive detection rate of repeated experience symptoms (e.g., persistent pain memories, nightmares, etc.) was the highest at 25.80%. This result reflects the psychologically solid memory and repeated experience of pain in KOA patients, an experience that may further exacerbate their psychological burden and risk of PTSD. KOA patients endure persistent and repeated pain for a long time, and multiple neurotransmitters are altered in the body39. During joint pain, the body will release inflammatory response-causing substances, such as calcitonin gene-related protein, substance P, prostaglandin E2, and serotonin40, which sensitize peripheral receptors. These mediators interact with each other to increase and maintain the body’s response to pain. When patients experience falls and fractures, they are overly careful and hypervigilant in their daily activities. Whenever pain strikes, patients frequently recall scenes of falls and injuries41. To cope with the internal fear and anxiety, patients may begin to avoid exposure to pain-producing activities or environments, such as sports, which limit limb movement and are not conducive to recovery. Symptoms of increased alertness followed this (e.g., easily startled, difficulty sleeping, etc.), with a positive detection rate of 21.90%. This may be related to the fact that KOA pain causes patients to experience an awakening from dreams, which triggers sleep disturbances, and that past symptoms of pain and joint abnormalities put patients on high alert, making it difficult for them to relax and rest.

Factors influencing post-traumatic stress disorder in elderly patients with knee osteoarthritis

In this study, education level, salary level, occupation type, weekly exercise frequency as well as smoking, leisure activities, and abnormal symptoms (stiffness, friction sounds) in the knee joint in the last month were the influencing factors for the development of PTSD in elderly KOA patients. First, patients with higher education and salary levels are less likely to develop PTSD, and this group can obtain authoritative knowledge about KOA treatment and rehabilitation through multiple channels, reducing the fear of lack of information. Patients with higher wage levels have a lower medical burden and a better environment to promote recovery. Unemployed patients are more likely to develop PTSD, considering that unemployment may lead to economic pressure, loss of social role, and a decrease in self-worth, thereby exacerbating psychological trauma. According to correlation analysis, patients’ pain levels are significantly and positively correlated with PTSD, and patients are thus prone to be positive for PTSD. In addition, patients who smoked had less daily exercise and had no leisure activities during the day were more likely to develop PTSD. It has been shown that KOA is a systemic disease that interacts with the patient’s psychological activity and social dysfunction (anxiety, depression, and other psychiatric disorders)42,43. Knee pain can be alleviated and disease recovery promoted through reasonable physical activity and healthy lifestyle habits, reducing the stress associated with joint pain, anxiety, and depression. Related studies44 have shown that re-experiencing a traumatic event or being in a relevant environment has a predictive power for PTSD. The present study confirms the conclusion that the recent symptoms of joint discomfort prompted patients to relieve severe pain, increased fear of disease exacerbation, and induced PTSD to some extent. Based on the above influences on patients’ general characteristics, it suggests that healthcare professionals need to comprehensively assess the condition of KOA patients, provide targeted treatment, and encourage a healthy lifestyle to enhance patients’ psychological resilience.

Direct effects of pain, anxiety, depression and social support on post-traumatic stress disorder in elderly patients with knee osteoarthritis

In this study, social support was negatively correlated with PCL-C; anxiety, depression, and pain were positively correlated, a finding that is consistent with the results of several national and international studies6,45,46,47,48. It shows that the above factors are equally induced in patients to develop PTSD related even if they did not undergo surgery. Increased anxiety, decreased ability of the patient to cope with the disease, difficulties in effectively dealing with the negative emotions that arise after each pain episode, and loss of sense of control and self-confidence elevate the risk of PTSD15. Yan Yan et al.17 showed that social support is a high-risk influencing factor affecting the occurrence of PTSD in orthopedic patients. Good social support can buffer the pressure of all parties and help patients cope with pain and negative emotions. On the contrary, patients lacking social support have increased feelings of loneliness and helplessness, inducing PTSD. Through structural equation modeling, depression was found to have a direct and significant positive effect on the development of PTSD in elderly KOA patients, with a path effect value of 0.701. This result emphasizes the central role of depression in the pathogenesis of PTSD in elderly KOA patients. It is similar to the findings of Gootzeit et al.46. Depression, which is usually characterized by persistent feelings of hopelessness and helplessness, not only affects the patient’s psychological well-being but may also exacerbate their perception of pain and dysfunction, thereby increasing the risk of PTSD16. Some studies have emphasized the role of strategies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy in reducing PTSD symptoms by addressing patients’ negative thought patterns49. This finding enlightens healthcare professionals to identify and assess depressive symptoms in elderly KOA patients early, and psychological screening tools such as the Hamilton Depression Inventory can be used regularly to detect depressive tendencies in a timely manner and implement strategies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy for counseling.

The mediating role of social support in post-traumatic stress disorder in elderly patients with knee osteoarthritis

This study revealed a significant mediating role of social support between pain and PTSD. Specifically, the lower the level of social support, the more severe the patients’ PTSD symptoms. Co-morbidity between pain and PTSD has been demonstrated12,50. The present study enriches the mediating role of social support between the two. Patients presenting with PTSD were associated with persistent pain, stress, and social isolation51. Elderly patients with KOA face dual stressors (i.e., recurrent knee pain triggering a physiologic stress response and pain-induced psychological stress of anxiety and depression). Social support provides an environment that facilitates psychological and physiological adaptation and may attenuate the association between pain and PTSD. On the one hand, social support has a buffering effect, reducing the psychological impact of pain and stress on the individual. On the other hand, social support enhances adaptation, promotes effective coping with stress, and reduces the risk of PTSD. Social support, as an essential psychological resource, reduces the risk of PTSD to a certain extent by alleviating patients’ fear and avoidance behavior toward pain-related traumatic events52. This result reveals that healthcare professionals should pay attention to social support, patients’ physical health, and pain relief when treating KOA. Good social support is good medicine to encourage patients to establish positive social connections, strengthen the supportive role of family and society, and provide patients with more psychological and emotional support to help them better utilize this resource to cope with the challenges of pain and PTSD.

Limitations

This study provides a reference point for investigating the current status of PTSD in older KOA patients. However, there are some limitations to this study. First, the cross-sectional study design did not allow for a more precise determination of causal relationships between variables. Second, the results of the main variables in this study were obtained subjectively through the respondents and there may be unavoidable recall bias. Third, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the data were collected over a short period of time, which may have affected the representativeness of the sample. In addition, pain characteristics (e.g., pain intensity and duration) may be potential risk factors for PTSD in patients with KOA, but they were not explored in depth in this study. Future studies should further explore the role of pain characteristics in the pathogenesis of PTSD in patients with KOA and assess the effectiveness of targeted interventions.

Conclusion

In this study, for the elderly patients with KOA who underwent surgery PTSD positive detection rate of 18.20%. Some of the general information is an influencing factor for PTSD positivity in patients, such as low level of education, low salary, and unemployment. In addition, pain, anxiety, depression, and social support were closely related to PTSD, with depression directly affecting the development of PTSD in elderly KOA patients; social support mediated the relationship between pain and PTSD. These findings reveal that PTSD is influenced by multiple factors and provide a theoretical basis for clinical intervention. Clinicians should pay attention to the psychological impact of pain in elderly patients with KOA, intervene promptly for depressive symptoms, and reduce the risk of PTSD by improving the level of social support.

Data availability

Data are available upon reasonable request. Please contact the corresponding author for data requests.

References

Driban, J. B. et al. Defining and evaluating a novel outcome measure representing end-stage knee osteoarthritis: Data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Clin. Rheumatol. 35, 2523–2530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-016-3299-5 (2016).

Xiaoyun, Z., Hao, Z. & Lin, M. Advances in the study of pain mechanisms and treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Chin. J. Pain Med. 29, 50–58. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1006-9852.2023.01.010 (2023).

Safiri, S. et al. Global, regional and National burden of osteoarthritis 1990–2017: A systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2017. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 79, 819–828. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216515 (2020).

Wojcieszek, A., Kurowska, A., Majda, A., Liszka, H. & Gądek, A. The impact of chronic pain, stiffness and difficulties in performing daily activities on the quality of life of older patients with knee osteoarthritis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416815 (2022).

Vitaloni, M. et al. Global management of patients with knee osteoarthritis begins with quality of life assessment: A systematic review. Bmc Musculoskelet. Disord. 20, 493. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-019-2895-3 (2019).

Hong, C., Li, L. I., Yan, Z. & Hui-Juan, C. Clinical study of posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic growth in orthopedic trauma inpatients. China J. Emerg. Resusc. Disaster Med. 17, 61–64. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1673-6966.2022.01.017 (2022).

Ozcetin, A. et al. Effects of depression and anxiety on quality of life of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, knee osteoarthritis and fibromyalgia syndrome. West. Indian Med. J. 56, 122–129. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0043-31442007000200004 (2007).

Neria, Y., Nandi, A. & Galea, S. Post-traumatic stress disorder following disasters: A systematic review. Psychol. Med. 38, 467–480. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291707001353 (2008).

Vriezekolk, J. E., Peters, Y., Steegers, M., Blaney, D. E. & van den Ende, C. Pain descriptors and determinants of pain sensitivity in knee osteoarthritis: A community-based cross-sectional study. Rheumatol. Adv. Pract. 6, rkac016. (2022).

Scioli-Salter, E. R. et al. The shared neuroanatomy and neurobiology of comorbid chronic pain and ptsd. Clin. J. Pain. 31, 363–374. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000115 (2015).

Xiaoting, Z. Mechanisms of nmdar-camkii in Anterior Cingulate Cortex Involved in the Rapid Fear Generalization Induced by Chronic Pain Bachelor’s Degree (Anhui University of Medical Science, 2023).

Fishbain, D. A., Pulikal, A., Lewis, J. E. & Gao, J. Chronic pain types differ in their reported prevalence of post -traumatic stress disorder (ptsd) and there is consistent evidence that chronic pain is associated with Ptsd: An evidence-based structured systematic review. Pain Med. 18, 711–735. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnw065 (2017).

Cremeans-Smith, J. K., Greene, K. & Delahanty, D. L. Symptoms of postsurgical distress following total knee replacement and their relationship to recovery outcomes. J. Psychosom. Res. 71, 55–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.12.002 (2011).

Long, G. et al. The impact of post-traumatic stress on the clinical outcome in a cohort of patients with knee osteoarthritis and knee arthroplasty: A prospective study. J. Orthop. Sci. 29, 847–853. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jos.2023.03.017 (2024).

Roth, M., King, L. & Richardson, D. Depression and anxiety as mediators of ptsd symptom clusters and pain in treatment-seeking Canadian forces members and veterans. Mil Med. 188, e1150. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usab532 (2023).

Baltjes, F., Cook, J. M., van Kordenoordt, M. & Sobczak, S. Psychiatric comorbidities in older adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review. Int. J. Geriatr. Psych. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5947 (2023).

Yan, Y., Chongjie, C., Qidong, Z., Weiguo, W. & Wanshou, G. Occurrence and high risk factors of post-traumatic stress disorder related to orthopedic surgery. Chin. J. Tissue Eng. Res. 24, 3897–3903. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.2095-4344.2713 (2020).

Castro-Dominguez, F. et al. Literature review to understand the burden and current non-surgical management of moderate–severe pain associated with knee osteoarthritis. Rheumatol. Therapy. 11, 1457–1499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-024-00720-y (2024).

. China to gradually raise retirement age amid demographic changes - cgtn. https://news.cgtn.com/news/2024-08-09/China-to-gradually-raise-retirement-age-amid-demographic-changes-1vVsIzwwS6k/p.html (2025-3-10).

Wang, J., Di, W. L., Jiaji, W., Peixi, W. & Zhiheng, Z. Surveying the status of social support on patients with hypertension in communities. Chin. Health Service Manag. 29, 394–397. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1004-4663.2012.05.025 (2012).

. Icd-11 for mortality and morbidity statistics. (2025). https://icd.who.int/browse/2025-01/mms/en#1685726407 -2-17).

Cma, C. O. A. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of osteoarthritis (2018 edition). Chin. J. Orthop. 38, 705–715. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2352.2018.12.001 (2018).

Airong, L. Statistics1 edn, p. 289 (Chongqing University, 2019).

Xiaoyun, Y., Hongai, Y., Qigui, L. & Lizhu, Y. Reliability and validity of Chinese version of the generalized anxiety disorder7-item(gad-7) scale in screening anxiety disorders in outpatients fromtraditional Chinese internal department. Chin. Mental Health J. 2007:6–9 https://doi.org/10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2007.01.003

Joos, E., Peretz, A., Beguin, S. & Famaey, J. P. Reliability and reproducibility of visual analogue scale and numeric rating scale for therapeutic evaluation of pain in rheumatic patients. J. Rheumatol. 18, 1269–1270 (1991).

Jensen, M. P., Turner, J. A., Romano, J. M. & Fisher, L. D. Comparative reliability and validity of chronic pain intensity measures. Pain (Amsterdam). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00101-3 (1999).

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. & Lowe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The gad-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 166, 1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 (2006).

Qingzhi, Z. et al. Reliability and validity of Chinese version of the generalized anxiety disorder7-item(gad-7) scale in screening anxiety disorders in outpatients from traditional Chinese internal department. Chin. Mental Health J. 27, 163–168. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2013.03.001 (2013).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. The phq-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 16, 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x (2001).

Yong, X., Haisu, W. & Yifeng, X. The reliability and validity of patient health questionnaire depression module (phq-9) in Chinese elderly. Shanghai Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2007.05.001 (2007).

Shuiyuan, X. Basis and research applications of the social support rating scale (ssrs). J. Clin. Psychiat. 4, 98–100 (1994).

Jiwen, L., Fuye, L. & Yulong, L. Investigation of reliability and validity of the social support scale. J. Xinjiang Med. Univ. 1–3 https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1009-5551.2008.01.001 (2008).

Bentler, P. M. & Bonett, D. G. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 88, 588–606. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588 (1980).

Marsh, H. W. & Balla, J. R. Goodness-of-fit indexes in confirmatory factor analysis: The effect of sample size. Psychol. Bull. 103 (3), 391–410 (1988).

Zhonglin, W. & Herbert, H. M. Structural equation modeling: Fit indices and chi-square criterion. Acta Physiol. Sinica. 36(02), 186–194 (2004).

Hoyle, R. H. The structural equation modeling approach: Basic concepts and fundamental issues. Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications 1–15 (Sage Publications Inc, 1995).

Zhao, R. et al. Pain empathy and its association with the clinical pain in knee osteoarthritis patients. J. Pain Res. 15, 4017–4027. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S379305 (2022).

Georgiev, T. Clinical characteristics and disability in patients with knee osteoarthritis: Real world experience from Bulgaria. Rheumatology 57, 78–84. https://doi.org/10.5114/reum.2019.84812 (2019).

Qian, L., Xiaoxia, L., Xu, H., Xiayuan, Z. & Yuchen, C. The impact of chronic pain on the physical and mental health of community-dwelling older adults. Beijing Med. 39, 1186–1187. https://doi.org/10.15932/j.0253-9713.2017.11.030 (2017).

Yam, M. F. et al. General pathways of pain sensation and the major neurotransmitters involved in pain regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 2164. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19082164 (2018).

Cai, Y., Leveille, S. G., Shi, L., Chen, P. & You, T. Chronic pain and circumstances of falls in community-living older adults: An exploratory study. Age Ageing. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afab261 (2022).

Dongmiao, L., Xin, L., Shu, L. & Qiaomei, C. Longitudinal study of post-traumatic stress disorder and social support in amputated patients. Chin. J. Nurs. 54, 965–969. https://doi.org/10.3761/j.issn.0254-1769.2019.07.001 (2019).

Bin, W. et al. Prevalence and disease burden of knee osteoarthritis in China: A systematic review. Chin. J. Evidence-Based Med. 18, 134–142. https://doi.org/10.7507/1672-2531.201712031 (2018).

Brewin, C. R., Andrews, B. & Valentine, J. D. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 68, 748–766. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.68.5.748 (2000).

Lapp, L. K., Agbokou, C. & Ferreri, F. Ptsd in the elderly: The interaction between trauma and aging. Int. Psychogeriatr. 23, 858–868. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610211000366 (2011).

Gootzeit, J. & Markon, K. Factors of Ptsd: Differential specificity and external correlates. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 31, 993–1003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.06.005 (2011).

Lei, L. et al. Study on the status and influencing factors of social support among urban community elderly residents. Chin. Health Service Manag. 31, 412–415 (2014).

Ruosong, Y., Mengshi, G. & Sang, Y. H. The mediating effects of hope and loneliness on the relationship between social support and social well-being in the elderly. Acta Psychologaca Sinica. 50, 1151–1158. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1041.2018.01151 (2018).

Boyd, J. E., Lanius, R. A. & Mckinnon, M. C. Mindfulness-based treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder: A review of the treatment literature and Neurobiological evidence. J. Psychiatr. Neurosci. 43, 7–25. https://doi.org/10.1503/jpn.170021 (2018).

Kind, S. & Otis, J. D. The interaction between chronic pain and ptsd. Curr. Pain Headache R. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-019-0828-3 (2019).

Rzeszutek, M., Oniszczenko, W., Schier, K., Biernat-Kałuża, E. & Gasik, R. Pain intensity, temperament traits and social support as determinants of trauma symptoms in patients suffering from rheumatoid arthritis and low-back pain. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 19, 412–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185X.12784 (2016).

Blais, R. K. et al. Self-reported ptsd symptoms and social support in U.s. Military service members and veterans: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Psychotraumato. 12, 1851078. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1851078 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all authors for their investment in the research design. Thank you also to the confirmed KOA patients who participated in the survey, who spent time and effort completing a quite tedious questionnaire.

Funding

This research was supported by Hunan Provincial Health High-Level Talent Scientific Research Project (grant number: R2023064) and Hunan Provincial Key Research and Development Program (grant number: 2024JK2133).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yang zhou: data analysis and thesis manuscript writing; Yang zhou*: data collection and monitoring and facilitation throughout; Yanping Liu: questionnaire design and data collection; Yabin Guo and Xiaotong Liu: manuscript revision and comments. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics and consent to participate

The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Clinical Medical Ethics Committee of Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (E2020133). The researchers explained the study to the participants and obtained informed consent from all participants. Participants were informed that their data would be used for research purposes only and that anonymity and confidentiality would be maintained. They were also told that they could withdraw from participation at any time without repercussions.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Y., Liu, Y., Guo, Y. et al. Analysis of the current status and factors influencing post-traumatic stress disorder in elderly patients with knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 15, 10253 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95212-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95212-6