Abstract

Over the past decades, drought events have led to significant agricultural losses and water shortages in the Algerian catchments; these hydro-meteorological phenomena strongly affect the entire Mediterranean region, and its frequency and intensity may increase due to climate change. The purpose of this study is to investigate drought conditions in the northern region of Algeria using the standardized precipitation index (SPI) at different monthly scales (3, 6, 12, 24 months), calculated through the ERA5-Land monthly dataset, which provides a much more detailed mapping of drought vulnerability across the country compared to observed rain gauge data, whose ground distribution is sparse and whose data archive is neither homogeneous nor complete for the study area. The main characteristics of drought events (e.g., quantity, duration, severity, and intensity), that have historically affected several hydrological basins in the northern part of the nation, are examined using the run theory applied to SPI values from 1950 to 2022. Although a high number of occurrences appear at shorter timescales, the results indicate that these episodes generally have shorter durations and lower severity compared to long-timescale droughts. Specifically, a decrease in the average number of drought events as the timescale increases is found: from 69 events for the 3-month SPI, with an average duration of about 2 months, to 17 events for the 24-month SPI, with an average duration of approximately 8 months. By analysing the spatial and temporal distribution of drought features, this approach aims to identify areas experiencing water stress and support more effective water management and mitigation strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to Svoboda et al.1, drought is an insidious plague that arises from a decrease in precipitation from levels considered normal. When the phenomenon lasts for a whole season, or for a longer period, water shortages affect the environment and human activities. Hence, drought must be considered a relative rather than an absolute state, and it is indeed mainly a regional scale phenomenon, since each area has its own climatic characteristics70. Historically, these events can occur in different ways and time intervals; for this reason, numerous drought classifications have been proposed2. One of the most common considers four various types of droughts3, i.e., meteorological (temporary lower-than-average precipitation), hydrological (scarcity in surface and subsurface water supplies), agricultural (water shortage compared to typical needs for crops irrigation), and socio-economic (referred to as global water consumption). In the territories located within the Mediterranean basin, a region highly vulnerable to climate change, several studies have focused on droughts (e.g.,4,5). Spinoni et al.6 reported a significant increase in drought frequency, duration, and severity in the Mediterranean region, while Giorgi and Lionello7 found a pronounced decrease in precipitation associated with a noticeable warming, mainly in the summer season. This drying condition is associated with an increased anticyclonic circulation, which yields progressively stable conditions, and a northward shift of Atlantic storm tracks. Future projections over north African regions exposed to the Mediterranean Sea suggest that such events will likely become more frequent due to climate change and precipitation deficits8,9.

In this context, the present study focuses on numerous hydrological catchments in northern Algeria where several drought and precipitation analyses have already been carried out in the past10. For instance, Demmak11 compared rainfall departures from the average in the period 1974–1992 with the one from 1913 to 1963, and he found drier conditions in the recent period, although some years were as dry as in the early series (e.g., 1913 and 1940). These rainfall deficits caused serious socio-economic problems, and anticipated future shortages that led to an increasing pressure on the scarce Algerian water resources, particularly, for drinking and irrigation supplies12.

According to the FAO water document number 4513, the effects of drought mostly affect the northern Algeria region, lowering dam water reserves, depleting rural drinking water sources, raising the salinity of water retentions, and reducing grain and fodder production. According to government reports, Algeria went through a devastating drought from 1945 to 1947. Nearly 90% of the cattle in the Ain Sefra region, south of Oran, perished, with 900,000 sheep destroyed and around 3000 people (out of a population of 80,000) starving to death. The lowest rainfall that Algeria had seen since 1945 occurred in early 1966, 20 years later, leading to poor crop germination and production loss. Between 1922 and 1992, there were multiple dry spells in the north, including 1910–1920, 1939–1948, and 1973–1992. They were marked by severe social unrest, wildfires, and starvation. The years 1973–1992, in particular, were extremely dry, having a negative effect on water resources due to decreased flows into dam storages, drops in groundwater levels, and dry springs and shallow wells. In the last 4 decades, multiple extreme and severe drought events hit the northern Algerian areas with significant impacts on agriculture, water resources, and local population14. In particular, it is worth noting: (i the drought in the 1980s which saw a prolonged and severe period in the north of the country: crop failures and livestock losses were reported, and communities faced challenges in accessing sufficient water for domestic and irrigation purposes; (ii) the drought in the 1990s, another notable period affecting the north of Algeria and other regions of the country; this drought led to significant decline in agricultural production, particularly in rain-fed agriculture. Water scarcity became a concern with reduced availability in reservoirs and groundwater sources; (iii) the drought of the exceptionally warm year 2003 when the north of Algeria, and even other regions in Europe15,16, experienced severe water shortages with devastating impacts on agriculture and water resources. The lack of precipitation resulted in reduced crop yields, food famines, and increased prices of staple crops leading to challenges in meeting domestic and agricultural water demands.

To evaluate drought assessment and trends, several drought indices have been used in literature, such as the SPI, standardized precipitation-evapotranspiration index (SPEI), percentile index (PI), palmer drought severity index (PDSI), rainfall anomaly index (RAI), combined drought indicator (CDI), standardized runoff index (SRI), standardized soil moisture index (SSI), and vegetation condition index (VCI). Due to their large variety, selecting the most appropriate index has been a key subject in recent research17,18,19. This selection process also depends on the purpose of the drought analysis, which is often used as an indicator for risk assessment and design purposes20,21. Based on the existing literature, the SPI and SPEI are the most commonly and widely used indices22. In this study, the SPI is chosen for its straightforward and simple approach since it relies only on precipitation data to calculate drought characteristics.

Originally developed by McKee et al.23, it quantifies precipitation deficits and surpluses relative to the long-term climatological average, providing a standardized measure of drought severity. The SPI is widely accepted and applied throughout the world in both research and on the field, because it is normalized to a specific location and time, thus allowing researchers to determine the rarity of a current drought event as well as the probability of precipitation necessary to end that given drought24. Nowadays, the World Meteorological Organization25 also recommends it as drought indicator. The SPI is based on the probability of accumulated precipitation for different time scales representing various types of drought: i.e., shorter time scales are used to assess meteorological droughts, and are often applied to agricultural ones too, whereas larger time scales are more suitable to describe hydrological and water resource droughts26. The probability of the observed precipitation is then transformed into an index enabling the evaluation of drought severity, and, potentially, offering an early warning for drought or assessing the influences of climate change27,28,29,30,31. The SPI can be considered a robust and effective clue for evaluating meteorological droughts, and it remains a very popular choice among researchers to reveal dry periods and to estimate the duration and intensity of drought events32. The SPI has, in fact, several advantages: firstly, it is based on rainfall data only,consequently, in absence of other hydro-meteorological measurements, drought assessment is still possible. Secondly, the SPI can be used to quantify precipitation deficit for multiple timescales, making it possible to evaluate drought conditions in meteorological, hydrological and agriculture applications. Finally, the standardization of the SPI index ensures that the frequency of extreme drought events at any location and timescale is approximately constant33,34.

Therefore, the SPI is here used to detail spatial and temporal variations of droughts, based on monthly records for the period 1950–2022 using the ERA5-Land monthly dataset over several hydrological basins in the north region of Algeria. This territory was the subject of various rainfall and drought studies, although mostly dedicated to the north-western areas, and rarely to north-east of the country, where several authors35,36,37 reported a decrease in precipitation totals. The idea to use the ERA5-Land spatially distributed gridded dataset, rather than the instrumental ground observations coming from the National Hydraulic Resources Agency (ANRH), is to cover the whole northern area with a complete and homogenized database to overall assess the number, severity, intensity and duration of droughts in a 73-year record.

The characterization of the SPI index proposed in this study aims to provide valuable information for various sectors, including economy, agriculture, water resource management, social-ecological systems, and disaster preparedness. In particular, it can help decision-makers and stakeholders understand drought conditions, estimate risks, plan for potential water shortages, and implement appropriate mitigation strategies over strategic basins of the country.

Study area

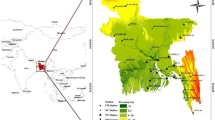

The study area is located in the northern part of Algeria, and it includes sixteen basins (Table S1, in the Supplementary Material): Cheliff, Algerian Coastal, Constantine Coastal, Oran Coastal, El-Hodna, Melrhir Chott, Constantine High Plateaus, Ech Chergui Chott, Isser, Kebir Rhumel, Macta, Medjerda Mellegue, Seybous, Soummam, Tafna, and Zahrez. This region extends from 2° 15′ 13″ W to 8° 40′ 10″ E and from 37° 7′ 2″ N to 32° 42′ 4″ N: it is delimited to the north by the Mediterranean Sea, to the west by Morocco, to the east by Tunisia, and to the south by the Sahara Desert (Fig. 1).

Northern Algeria offers a rich mosaic of landscapes due to its 1200 km of Mediterranean coastline, its twin Atlas Mountain chains with high altitudes, and its extensive high plateaus and plains, with different land cover characteristics (as shown in Table S2 and Figure S1 in the Supplementary Material). The region, with a total area of approximately 294,700 km2, represents about 19.46% of the country.

Due to its geographic location and complex topography, the research area exhibits substantial spatial variability in precipitation and temperature. In fact, Algeria is subject to unfavourable hydro-climatic conditions, typically of arid and semi-arid regions, characterized by climate that varies from south to north: desert in the south Sahara, a semi-arid continental on the high plateaus, and Mediterranean along the northern fringe of the country, marked by harsh winters, torrential and irregular rainfall, and hot, dry summers. This dry season in northern Algeria lasts from July to October with most of the precipitation amount between October and April38, a common characteristic of the Mediterranean, with mild, wet winters and hot, dry summers.

Furthermore, the hydrological regimes are dominated by extremely irregular seasonal and inter-annual flows, violent and rapid flooding, and significant erosion and sediment transport. The investigated basins are characterized by predominantly marly geological formations, impermeable soils, accentuated relief, and sparse plant cover. The groundwater in the north is practically at the limits of its exploitation, and surface water, which accounts for two-thirds of the country’s resources, remains irregular, making it difficult to withdraw considerable volumes. Although resource scarcity is a reality, this problem is exacerbated by poor spatial distribution of water resources and the mismatch between supply and demand, requiring major water transfers to meet the needs of less well-endowed regions. Additional challenges include the seasonal and inter-annual irregularity of runoff, the silting up of dams, and enormous water losses due to aging infrastructure and poor management. Thus, the distribution of water resources across the country is closely linked to rainfall patterns, which exhibit a gradient of variation from east to west and from north to south. Figure 2 shows the precipitation data over the investigated hydrological basins in the period 1950–2022 calculated with the ERA5-Land dataset. In particular, accumulated precipitation follows a latitudinal distribution with higher records around 1000 mm in a year in northeastern basins, close to the Mediterranean Sea, while, moving south, average yearly rainfall dramatically drops to desert values, lower than 200 mm. However, significant variabilities in precipitation from year to year may be present, leading to various periods of drought which are here evaluated thought the SPI index and characterized at catchment scale.

Materials and methods

In this section, a detailed overview of the employed dataset and associated methodology to evaluate climatological data is provided. The SPI is used to characterize drought conditions in the north of Algeria by analysing 3983 grid points for a long series of precipitation data.

The ERA5-Land reanalysis

The ERA5-Land dataset, developed by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) under the framework of the Copernicus Climate Change Service Programme, provides high-quality reanalysis data for various climate variables, including precipitation. This dataset is here applied to analyse the SPI values, which provide insights into the severity, intensity, and duration of drought conditions in northern Algerian catchments. The ERA5-Land is a reanalysis database with a consistent view of the evolution of land variables for several decades at an enhanced spatial resolution of 9 km (0.08°). For a detailed description of the ERA5-Land dataset, the reader can refer to Muñoz-Sabater et al.39, and the online documentation: https://confluence.ecmwf.int/display/CKB/ERA5-Land%3A+data+documentation, accessed on 1 December 2023.

In this paper, we analyse all values at monthly time scale from 1 January 1950 until 31 December 2022, i.e., 73 years of data are considered. Indeed, it is a complete archive, useful to understand climate variability, mainly in terms of temperature and precipitation for hydrological purposes and water resources over the investigated area. In addition, since the ground distribution of observed rainfall is scarce in the investigated territory, mostly under desert conditions, and the available historical data are not homogenous and complete, the ERA5-Land values are here used as they stand, without any post-processing algorithm; however, a comparison with existing rainfall series is added in the Supplementary Material section.

The SPI index

Following Angelidis et al.40 in the SPI calculation, the gamma function is considered as the most appropriate equation in fitting the frequency distribution of the accumulated precipitation at each time scale. Consequently, for each month of the year and for each time aggregation, the shape and scale parameters are estimated using the approximation of Thom41. Moreover, in order to consider the zero values that occurred in the sample set, since the gamma distribution is undefined for a null rainfall amount, a modified cumulative distribution function (CDF) is used (Eq. 1):

where G(x) is the CDF, and q is the probability of zero precipitation, given by the ratio between the number of zero in the rainfall series (m) and the number of observations (n).

Afterwards, by using the approximate conversion provided by Abramowitz and Stegun42, the CDF is changed into the standard normal distribution (Eqs. 2 and 3):

where c0, c1, c2, d1, d2 and d3 are mathematical constants.

Although the first SPI classification referred to drought periods only, nowadays the SPI is also used in the classification of wet periods as reported in Table 1.

The run theory

The run theory was first proposed by Yevjevich43, and it is still considered one of the most effective methods in the analysis of time series44. It refers to the occurrence of similar events, like droughts, and makes it possible to describe each episode by assessing some characteristics such as duration, severity, and intensity. An example of the run theory for a specified threshold level is shown in Fig. 3. In this paper, the SPI threshold equal to − 1 is selected to consider drought, only from moderate to extreme classes, because mild drought is often classified as normal conditions. For this reason, all episodes below this threshold are grouped as drought events with a minimum duration of 1 month.

Afterwards, the drought time series is analyzed using the proposed methodology of the run theory, wherein consecutive values constantly above or below the threshold are defined as runs. Positive runs are observed when values remain above this threshold, while negative runs occur when values persistently fall below it45. Once the drought events (runs) are identified, various drought characteristics are evaluated. In particular, the drought duration (DD) refers to the period during which drought values consistently remain below threshold and can be measured in weeks, months, years, or any other defined period.

where t1 and t2 are the onset and termination time of drought. The average drought duration (ADD) is computed by summing up the DD for all events and dividing it by the total number of events, denoted by N.

Similarly, the accumulated drought values for each event represent drought severity (DS).

where SPIi is the SPI value in the defined time period. The average drought severity (ADS) is obtained by summing up the DS of all events and dividing it by N.

To assess the drought intensity (DI) for each event, the ratio between DS and DD is computed.

Consequently, the average drought intensity (ADI) is derived by summing up the DI of all events and dividing it by N. In this study, the SPI series at different temporal scales (3, 6, 12, 24 months) is applied to estimate drought duration, severity, and intensity using the theory of runs, and, thus, the results express the DD in terms of months.

Results

This section depicts the main achievements found over the northern area of Algeria. Spatial and temporal analyses are described for different SPI values to assess drought characteristics in the investigated basins.

First, to evaluate the accuracy of the ERA5-Land dataset in reproducing rainfall across the study area, a validation is conducted. Among the various metrics commonly applied to assess the skill of rainfall reproduction, this study uses the Pearson correlation coefficient which is an important measure widely employed in climate sciences to evaluate data from independent sources, such as rainfall values from gauge stations and reanalysis datasets46,47. Since the study area is a data-scarce region, the validation is performed on three rainfall series only, based on the availability of weather station data, at either monthly or annual scale. The results yield correlation values higher than 0.5 which are reported in Figure S2 in the Supplementary Material. These findings align with similar results obtained in other African regions (e.g.,48), and worldwide (e.g.,49) in areas with sparse rain gauge networks where the ERA5-Land dataset has nonetheless proven to be one of the best-performing reanalysis methods and a valuable tool for assessing climate evolution.

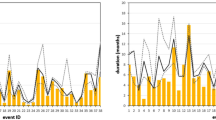

Temporal analysis of drought events

The percentages of grid points with SPI values lower than − 1 for each month in the observation period and for each temporal aggregation (SPI 3, 6, 12, 24) are illustrated in Fig. 4. Generally, dry events can be identified in every decade for all the temporal aggregations, but they are more frequent and extensive from 1980 onwards, when peaks of percentages higher than 90% can be observed. In particular, as regards the 3-month SPI, more than 90% of grid points showed drought conditions in the years 1954, 1956, 1960, 1964, 2002, 2016 and, especially 2000 when, in March, all the study area was affected. As regards the 6-month SPI, values lower than − 1 are identified in more than 90% of the grid point in 1954, 1956, 1958, 1962, 1964, 1997, 2001 and 2008. As regards both the 12-month and 24-month SPIs, the 2000–2002 period was one of the periods with the most frequent and extensive dry events. In particular, considering the 12-month SPI, more than 90% of the grid points show drought conditions in 1957, 1962, 1983, 2000 and 2002, while for the 24-month SPI these percentages are detected from 2000 onwards, in 2001, 2002, 2021 and 2022.

Statistics of the drought characteristics

The statistics associated with different drought characteristics N, ADD, ADS, and ADI are assessed using box plots (Fig. 5).

Characterization through boxplots of the number of drought events (N), average drought duration (ADD), average drought severity (ADS), and average drought intensity (ADI). The top and bottom of the boxes are the third and second quartiles, respectively; the band inside the box is the median, and the ends of the whiskers represent the minimum and maximum of all data.

Obviously, N decreases with the increase of the time scale. In fact, an average and a maximum of 68 and 84 events, respectively, are detected in the observation period (1950–2022) for the 3-month SPI; instead, as regards the 24-months SPI, the average and the maximum number of events correspond to 17 and 34 events, respectively. The statistics of the ADD show an opposite behavior than N, with the lowest values corresponding to the 3-month SPI, and the highest to the 24-month SPI. Moreover, different spreads are evident among the different scales. In fact, while for the 3-month SPI, the ADD does not present a large range of values (between 1.7 and 2.6 months), conversely, for the 24-month SPI, the ADD maximum value is higher than 18 months. A behavior similar to ADD is detected for the ADS at different temporal scales. The mean ADS value ranges from about 3 (3-month SPI) to 12.5 (24-month SPI). In addition, the ADS spread rises increasing the temporal scale, with minimum and maximum values ranging from 1.7 to about 4 for the 3-month SPI, and from about 4 to more than 32 for the 24-month SPI. Finally, there are not many differences in the ADI values among the various temporal scales, with an average value of about 1.3 months.

Spatial distribution of the drought characteristics

In the following pictures (6, 7, 8, and 9), the spatial distributions about N, ADD, ADS, and ADI are displayed considering the 3-, 6-, 12-, 24-SPI index values shown in the upper left, upper right, bottom left, and bottom right corner in each figure, respectively. Regarding the spatial distribution of N (Fig. 6) for the 3-month SPI, the highest N values (also higher than 80) are observed in the northern part of the study area: i.e., in the Tafna basin (ID 16), in the Oran (ID 4), and in the Algerian coastal basins (ID 2). Similar spatial distributions are obtained for the 6-, 12- and 24-month SPI with the highest N reaching values higher than 60, 40 and 30, especially in the northeastern side of the study area for the 6-, 12- and 24-month SPI, respectively. As regards the 6-month SPI, the Oran coastal basin (ID 4), the Tafna basin (ID 16), the Macta basin (ID 11), the Cheliff basin (ID 1), and the Algerian coastal basin (ID 2) are identified as the mostly affected areas by drought events. In addition to these latter basins cited for the 6-month SPI, with respect to the 12-month SPI, a high number of drought events (between 55 and 60) is detected in the Melrhir Chott (ID 6) and El Hodna (ID 5) basins as well. Finally, for the 24-month SPI, only the Cheliff (ID 1) and the Melrhir Chott (ID 6) basins showed remarkable N values (> 30).

Concerning the spatial distribution of the ADD (Fig. 7), it is evident that the more frequent episodes are those with lowest durations; in fact, the areas with the highest ADD are concentrated in the regions presenting the lowest N values. In particular, the 3- and the 6-month SPI show the highest ADD (more than 2.5 and 3.5 months, respectively) mainly in the eastern part of the study area: i.e., in the Melrhir Chott (ID 6), the Constantine high plateaus (ID 7), the Medjerda Mellegue (ID 12), and in the Seybous (ID 14) basins. On the contrary, for the 12- (greater than 6.5) and 24-month SPI (greater than 14) the highest ADD are located in the western part of northern Algeria, in the Tafna (ID 16), the Macta (ID 11), and in the Ech Chergui Chott (ID 8) basins.

The spatial distribution of the ADS (Fig. 8) is very similar to the one of the ADD with the highest ADS values, mainly in the eastern part of the study area for the 3- (higher than 3.5) and 6-month SPI (higher than 5.5), and in the western part for the 12- (higher than 10) and 24-month SPI (higher than 18). Differently from the ADD spatial distribution, high ADS values are also identified in the Tafna (ID 16), the Macta (ID 11), and in the Ech Chergui Chott (ID 8) basins for the 3-month SPI, while in the Cheliff (ID 1) and in the Constantine coastal basins (ID 3) for the 24-month SPI.

As regards the spatial distribution of the ADI values (Fig. 9), the highest ones are localized in small regions randomly distributed in the study area for almost all the time scales, reaching values higher than 1.55 months−1 for the 3- and 6-month SPI, and higher than 1.5 for the 12- and 24-month SPI. In particular, the highest ADI values are mainly identified in the Cheliff basin (ID 1) the 3-month SPI, in the Algerian coastal basin (ID 2) for the 6-month SPI, and in the Constantine coastal basin (ID 3) for the 12- and 24-month SPI.

Discussion

In most African countries, the agricultural sector is especially susceptible to the negative impacts of drought hazards. Nearly 80% of all direct consequences of drought fall on this sector, resulting in significant economic losses and food scarcity for local populations50,51. In particular, northern Algeria, presenting a Mediterranean climate, experienced significant variability in precipitation and recurrent drought events that had profound effects on water resources, agriculture, and socio-economic stability. Therefore, conducting a thorough drought analysis in this region is essential for developing effective water management strategies and ensuring sustainable development.

Several studies on meteorological drought in Algeria have been recently carried out using the SPI52,53,54, but only at the basin scale, without an in-depth investigation at large scale. Differently from the past, in this study, meteorological droughts are analyzed in the whole northern part of country, using the SPI index throughout various accumulation periods, namely 3, 6, 12, and 24 months, examining precipitation data coming from the ERA5-Land database in the period 1950–2022. This gridded dataset turned out to be a useful tool, since ground rainfall observations are often unavailable and scarce in the investigated basins to perform an accurate analysis, especially important in this region with limited and erratically distributed natural water resources.

In addition, the study selected the SPI, which uses only rainfall data to assess drought characteristics, due to its simplicity and straightforward methodology. The SPI’s main strength lies, in fact, in its well-accepted probability distribution fitting and the transformation of resulting probabilities to the standard normal distribution. Its weakness, however, is the treatment of zero-precipitation records, assigning them the probability of zero precipitation, which can incorrectly classify them as moderately to extremely wet if zero precipitation is normal for a region55. Although SPEI may lead to more robust drought analysis, particularly in arid regions, there is an acceptable level of agreement between SPI and SPEI ratings at all timescales56. Hence, it is reasonable to assume that the SPI can be used to assess droughts in the study area to make knowledge-driven decisions57.

The analysis of the temporal behaviour of the percentage of grid points with SPI values less than − 1 allowed us to identify the major drought events that have increasingly impacted the region, particularly from around 1980 onwards, due to the significant decline in precipitation occurred from the late 1970s, as reported by several studies (e.g.,58), and during the first decade of the 2000s, consistent with patterns across the entire Mediterranean region according to Hoerling et al.59. These conditions had a severe impact on agriculture and water resources, leading to reduced crop yields and strained water supplies.

The use of the run theory method to analyze meteorological drought better reflects actual water resource issues. In fact, by analyzing historical values, different drought characteristics (i.e., the number of drought events, the average drought duration, the average drought severity, and average drought intensity) are investigated as a tool to assess the impact at different temporal and spatial scales on human activities, such as agriculture and water resource management in northern Algerian catchments, where water scarcity is an actual concern. Outcomes of the run method let us to detect the most drought-prone areas in the northern part of the country. As a result, for various drought features and for different SPI time scales, the Cheliff, the Tafna and the Macta basins are identified as the main catchments affected by drought. This result is particularly relevant, given the importance of the watersheds involved. In fact, the Cheliff is the largest river basin in the whole nation. Supplying water for irrigation and supporting various crops, including cereals, vegetables, and fruits, is crucial for agricultural activities, but frequent droughts have led to reduce river flow, decrease reservoir levels, and significant agricultural losses60. The Tafna is another important basin for local agriculture and water supply, but it experienced several droughts as well, resulting in reduced water availability for irrigation and domestic use, amplified by the cross-border water management issues with Morocco61. The Macta basin and its associated wetlands are critical for agriculture and biodiversity, even though drought conditions led to significant reductions in water levels, affecting both agricultural activities and wetland ecosystems62. These findings agree with past studies that identified some of the most drought-prone areas. Taibi and Souag63 noted that the northwestern and central highland regions suffered severe droughts during the 1970s and 1980s. Derdous et al.64 highlighted substantial inter-annual rainfall variability in the Cheliff Basin, also in northwestern Algeria. This catchment underwent a long-wet cycle from 1938 to 1976, which was followed by a prolonged drought one from 1977 to 2008, featuring a rainfall deficit of approximately 20%.

Lastly, it is worth highlighting that numerous investigations have aimed to determine which climatic factors are connected with droughts. Many researchers65,66,67,68 offered evidence that rainfall and drought are strongly linked to general atmospheric circulation patterns in the Mediterranean regions, such as the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), the Mediterranean Oscillation (MO), the Western Mediterranean Oscillation (WeMO), and especially, the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) indices69),all these indices are negatively correlated with precipitation in Algeria58. Except for the WeMO, all the others are identified as primary atmospheric drivers for rainfall variability in northwestern Algeria,on the contrary, rainfall and drought variability in northeastern Algeria did not appear to be associated with any of the recognized atmospheric circulation patterns.

Conclusions

The north of Algeria experienced periods of severe drought in the past, leading to environmental degradation, a reduction in agricultural activity, and a depletion of water supplies, particularly from 1980 onwards.

The aim of this study was to analyse some of the main characteristics (quantity, duration, severity, and intensity) of drought events that affected the northern part of the country between 1950 and 2022, using the SPI values calculated from the ERA5-Land dataset at short (3- and 6-month) and long (12- and 24-month) timescales. Monthly precipitation data were examined to determine which basins were most affected by droughts over the last 70 years. This is an essential information, particularly in a dry region, for assessing climate patterns and human activities such as water resource management and agricultural strategies within the framework of global warming.

According to the climatological data from the ERA5-Land reanalysis, results clearly indicate that, when considering the 3- and 6-month SPI, which reflect droughts affecting vegetation and agricultural practices, several drought episodes could be expected, though they tend to be of short duration and low severity. On the contrary, when considering the 12- and 24-month SPI, which serve as a broad proxy for water resource management, fewer but more severe drought events could have an impact on the Algerian territory. Finally, based on the spatial distribution of drought characteristics, catchment areas facing water stress, such as the Cheliff, the Tafna, and the Macta, are identified. This highlights the need for a strong adaptation strategy in those areas, along with reliable monitoring and forecasting systems for drought events.

Further investigations could be conducted to enhance the present drought analysis by detecting additional drought features such as maximum duration, maximum severity, maximum intensity, and rapidity; this latter being particularly hazardous for flash droughts. Lastly, analysing decadal climatic predictions, the proposed methodology could provide drought scenarios to support long-term planning and management over these Algerian hydrological basins.

Data availability

The dataset generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- FAO:

-

Food and Agriculture Organization

- SPI:

-

Standardized precipitation index

- WMO:

-

World Meteorological Organization

- ECMWF:

-

European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts

- ANRH:

-

National Hydraulic Resources Agency

- DD:

-

Drought duration

- ADD:

-

Average drought duration

- DS:

-

Drought severity

- ADS:

-

Average drought severity

- DI:

-

Drought intensity

- ADI:

-

Average drought intensity

- N:

-

Number of drought events

References

Svoboda M., Hayes M. & Wood D. For the standardized precipitation index. User Guide. WMO-N°1090. Geneva. World Meteorological Organization. ISBN 978–92–63–11090–9 pp. 16 (2012).

Merabti, A., Darouich, H., Paredes, P., Meddi, M. & Pereira, L. S. Assessing spatial variability and trends of droughts in eastern Algeria using SPI, RDI, PDSI, and MedPDSI—a novel drought index using the FAO56 evapotranspiration method. Water 15, 626. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15040626 (2023).

Zargar, A., Sadiq, R., Naser, B. & Khan, F. I. A review of drought indices. Environ. Rev. 19, 333–349 (2011).

Buttafuoco, G., Caloiero, T., Ricca, N. & Guagliardi, I. Assessment of drought and its uncertainty in a southern Italy area (Calabria region). Measurement 113, 205–210 (2018).

Merabti, A. et al. Comparing SPI and RDI applied at local scale as influenced by climate. Water Resour. Manag. 32, 1071–1085. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-017-1855-7 (2018).

Spinoni, J., Naumann, G., Carrao, H., Barbosa, P. & Vogt, J. World drought frequency, duration, and severity for 1951–2010. Int. J. Climatol. 34, 2792–2804 (2014).

Giorgi, F. & Lionello, P. Climate change projections for the Mediterranean region. Glob. Planet Change 63, 90–104 (2008).

Balting, D. F. et al. Northern hemisphere drought risk in a warming climate. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 4, 61. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-021-00218-2 (2021).

Driouech, F. et al. assessing future changes of climate extreme events in the CORDEX-MENA region using regional climate model ALADIN-climate. Earth Syst. Environ. 4, 477–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41748-020-00169-3 (2020).

Habibi, B., Meddi, M., Torfs, P. J. J. F., Remaoun, M. & Van Lanen, H. A. J. Characterisation and prediction of meteorological drought using stochastic models in the semi-arid Chéliff–Zahrez basin (Algeria). J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 16, 15–31 (2018).

Demmak, A. Contribution à l’étude de l’érosion et des transports solides en Algérie septentrionale. Thèse de Docteur Ingénieur, université de Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris XI (1982).

Khaldi, A. Impacts de la Sécheresse sur le Régime des Ecoulements Souterrains Dans les Massifs Calcaires de l’Ouest Algérien “Monts de Tlemcen-Saida”. Thèse de doctorat d’état, Université d’Oran, Oran, Algérie, 239 (2005).

FAO. Drought characteristics drought characteristics and management in North Africa and the Near East North Africa and the Near East. FAO Water Reports 45, 266p (2018).

Achite, M., Krakauer, N. Y., Wałęga, A. & Caloiero, T. Spatial and temporal analysis of dry and wet spells in the Wadi Cheliff Basin, Algeria. Atmosphere 12(6), 798. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos12060798 (2021).

Ciais, P. et al. Europe-wide reduction in primary productivity caused by the heat and drought in 2003. Nature 437, 529–533. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03972 (2005).

Rebetez, M. et al. Heat and drought 2003 in Europe: A climate synthesis. Ann. For. Sci. 63, 569–577 (2006).

Fioravanti, G. et al. A dataset for monitoring agricultural drought in Europe. Sci. Data 12, 308. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04199-8 (2025).

Şişman, E. Self-similar characteristics of drought duration, total deficit, and intensity curves. Arab. J. Geosci. 13(1), 8 (2020).

Wable, P. S., Jha, M. K. & Shekhar, A. Comparison of drought indices in a semi-arid river basin of India. Water Resour. Manag. 33, 75–102 (2018).

Abu Arra, A. & Şişman, E. Characteristics of hydrological and meteorological drought based on intensity-duration-frequency (IDF) curves. Water 15, 3142. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15173142 (2023).

Abu Arra, A., Alashan, S. & Şişman, E. Trends of meteorological and hydrological droughts and associated parameters using innovative approaches. J. Hydrol. 640, 131661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2024.131661 (2024).

Abu Arra, A. & Şişman, E. A comprehensive analysis and comparison of SPI and SPEI for spatiotemporal drought evaluation. Environ. Monit. Assess. 196, 980. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-024-13127-7 (2024).

McKee, T.B., Doesken, N.J. & Kleist, J. The relationship of drought frequency and duration to time scales. In Proceedings of the 8th Conference on Applied Climatology, Anaheim, CA, USA 179–184 (1993).

Wu, H., Svoboda, M. D., Hayes, M. J., Wilhite, D. A. & Wen, F. Appropriate application of the standardized precipitation index in arid locations and dry seasons. Int. J. Climatol. 27, 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.1371 (2007).

WMO, Drought Monitoring and Early Warning: Concepts, Progress and Future Challenges, WMO-No. 1006. World Meteorological Organization, Geneva, Switzerland 26 (2006).

Mishra, A. K. & Singh, V. P. A review of drought concepts. J. Hydrol. 391, 202–216 (2010).

Bordi, I., Fraedrich, K. & Sutera, A. Observed drought and wetness trends in Europe: An update. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 13, 1519–1530 (2009).

Buttafuoco, G. & Caloiero, T. Drought events at different timescales in southern Italy (Calabria). J. Maps 10, 529–537 (2014).

Moreira, E. E., Coelho, C. A., Paulo, A. A., Pereira, L. S. & Mexia, J. T. SPI-based drought category prediction using loglinear models. J. Hydrol. 354, 116–130 (2008).

Moreira, E. E., Pires, C. L. & Pereira, L. S. SPI drought class predictions driven by the North Atlantic Oscillation index using log-linear modelling. Water 8, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/w8020043 (2016).

Paulo, A. A. & Pereira, L. S. Drought concepts and characterization: comparing drought indices applied at local and regional scales. Water Int. 31, 37–49 (2006).

Bordi, I., Fraedrich, K., Jiang, J.-M. & Sutera, A. Spatio-temporal variability of dry and wet periods in eastern China. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 79, 81–91 (2004).

Hayes, M. J., Svoboda, M. D., Wilhite, D. A. & Vanyarkho, O. V. Monitoring the 1996 drought using the standardized precipitation index. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 80, 429–438 (1999).

Lloyd-Hughes, B. & Saunders, M. A. A drought climatology for Europe. Int. J. Climatol. 22, 1571–1592 (2002).

Hamlaoui-Moulai, L., Mesbah, M., Souag-Gamane, D. & Medjerab, A. Detecting hydro-climatic change using spatiotemporal analysis of rainfall time series in Western Algeria. Nat. Hazards 65, 1293–1311 (2013).

Meddi, M., Assani, A. & Meddi, H. Temporal variability of annual rainfall in the Macta and Tafna catchments, northwestern Algeria. Water Resour. Manag. 24, 3817–3833 (2010).

Zeroual, A., Meddi, M. & Bensaad, S. The impact of climate change on river flow in arid and semi-arid rivers in Algeria. In Climate and land-surface changes in hydrology, proceedings of H01, IAHS-IAPSO-IASPEI Assembly, vol 359., 105–110 (IAHS Publ, Gothenburg, 2013).

Ghenim, A. N. & Megnounif, A. Variability and trend of annual maximum daily rainfall in northern Algeria. Int. J. Geophys. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/6820397 (2016).

Muñoz-Sabater, J. et al. ERA5-Land: A state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 4349–4383 (2021).

Angelidis, P., Maris, F., Kotsovinos, N. & Hrissanthou, V. Computation of drought index SPI with alternative distribution functions. Water Resour. Manag. 26, 2453–2473 (2012).

Thom, H. C. S. A note on the gamma distribution. Mon. Weather Rev. 86, 117–122 (1958).

Abramowitz, M. & Stegun, I. A. Handbook of mathematical functions with formulas, graphs, and mathematical tables (Dover Publications Inc, 1970).

Yevjevich, V. An objective approach to definitions and investigation of continental hydrologic droughts. In Hydrology Paper 23; Colorado State University: Fort Collins, CO, USA (1967).

Kim, Y., Kim, S., Jeong, H. & An, H. Quantitatively defining megadrought based on drought events in central Chile. Geomat. Nat. Haz. Risk 13, 975–992 (2022).

Caloiero, T., Caroletti, G. N. & Coscarelli, R. IMERG-based meteorological drought analysis over Italy. Climate 9, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli9040065 (2021).

Hennemuth, B. et al. Statistical methods for the analysis of simulated and observed climate data, applied in projects and institutions dealing with climate change impact and adaptation. CSC Rep. 13, 1–135 (2013).

Schönwiese, C. D. Praktische Statistik für Meteorologen und Geowissenschaftler 4th edn. (Borntraeger, 2006) (in German).

Ahmed, J. S., Buizza, R., Dell’Acqua, M., Demissie, T. & Pè, M. E. Evaluation of ERA5 and CHIRPS rainfall estimates against observations across Ethiopia. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 136, 17 (2024).

Liu, R. et al. Global-scale ERA5 product precipitation and temperature evaluation. Ecol. Indic. 166, 112481 (2024).

Ha, T. V., Huth, J., Bachofer, F. & Kuenzer, C. A review of earth observation-based drought studies in Southeast Asia. Remote Sens. 14, 3763. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14153763 (2022).

Pourzand, F. & Noy, I. Catastrophic droughts and their economic consequences. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Environmental Science. Retrieved 10 June 2023, from https://oxfordre.com/environmentalscience/view/https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199389414.001.0001/acrefore-9780199389414-e-689 (2022).

Berhail, S. et al. Geo-statistical assessment of meteorological drought in the context of climate change: Case of the Macta basin (Northwest of Algeria). Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 8, 81–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-020-01055-7 (2022).

Fellag, M., Achite, M. & Walega, A. Spatial-temporal characterization of meteorological drought using the standardized precipitation index. Case study in Algeria. Acta Sci. Pol. Form. Circumiectus 20, 19–31 (2021).

Haied, N. et al. Spatial and temporal assessment of drought hazard, vulnerability and risk in three different climatic zones in Algeria using two commonly used meteorological indices. Sustainability 15(10), 7803. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107803 (2023).

Raziei, T. & Pereira, L. S. Relating the drought precipitation percentiles index to the standardized precipitation index (SPI) under influence of aridity and timescale. Water Resour. Manag. 38, 5739–5758. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-024-03932-7 (2024).

Tefera, A. S., Ayoade, J. O. & Bello, N. J. Comparative analyses of SPI and SPEI as drought assessment tools in Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 1265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1326-2 (2019).

Berhail, S. & Katipoğlu, O. M. Comparison of the SPI and SPEI as drought assessment tools in a semi-arid region: Case of the Wadi Mekerra basin (northwest of Algeria). Theor. Appl. Climatol. 154, 1373–1393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-023-04601-2 (2023).

Meddi, H., Meddi, M. & Assani, A. A. Study of drought in seven Algerian plains. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 39, 339–359 (2014).

Hoerling, M. et al. On the increased frequency of Mediterranean drought. J. Clim. 25, 2146–2161. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00296.1 (2012).

Achite, M., Wałęga, A., Toubal, A. K., Mansour, H. & Krakauer, N. Spatiotemporal characteristics and trends of meteorological droughts in the Wadi Mina Basin, Northwest Algeria. Water 13, 3103. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13213103 (2021).

Bougara, H., Hamed, K. B., Borgemeister, C., Tischbein, B. & Kumar, N. A comparative assessment of meteorological drought in the Tafna basin Northwestern Algeria. J. Water Land Dev. 51, 78–93. https://doi.org/10.24425/jwld.2021.139018 (2021).

Elouissi, A. et al. Drought investigation and trend assessment in Macta watershed (Algeria) by SPI and ITA methodology. Arab. J. Geosci. 14, 1329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-021-07670-7 (2021).

Taibi, S. & Souag, D. Regionalization of drought in northern Algeria using a standardized precipitation index (1936–2010). In From prediction to prevention of hydrological risk in Mediterranean countries. 4th International Workshop on Hydrological Extremes. University of Calabria, Cosenza, Italy 169–182 (2011).

Derdous, O., Bouamrane, A. & Mrad, D. Spatiotemporal analysis of meteorological drought in a Mediterranean dry land: Case of the Cheliff basin–Algeria. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 7(1), 135–143 (2021).

Derdous, O., Bouguerra, H., Tachi, S. E. & Bouamrane, A. A monitoring of the spatial and temporal evolutions of aridity in northern Algeria. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 142(3), 1191–1198 (2020).

Hallouz, F. et al. Analysis of meteorological drought sequences at various timescales in semi-arid climate: Case of the Cheliff watershed (northwest of Algeria). Arab. J. Geosci. 13(6), 1–15 (2020).

Taibi, S., Meddi, M., Mahé, G. & Assani, A. Relationships between atmospheric circulation indices and rainfall in Northern Algeria and comparison of observed and RCM-generated rainfall. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 127, 241–257 (2017).

Zeroual, A., Assani, A. A. & Meddi, M. Combined analysis of temperature and rainfall variability as they relate to climate indices in northern Algeria over the 1972–2013 period. Hydrol. Res. 48(2), 584–595 (2017).

Caloiero, T., Veltri, S., Caloiero, P. & Frustaci, F. Drought analysis in Europe and in the Mediterranean basin using the standardized precipitation index. Water 10(8), 1043 (2018).

Bendjema L., Baba-Hamed K., Bouanani A. Characterization of the climatic drought indices application to the Mellah catchment, North-East of Algeria. Journal of Water and Land Development. 43(X–XII), 28–40. https://doi.org/10.2478/jwld-2019-0060 (2019).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the research help received during the Project PNRR - CN - AGRITECH - SPOKE 3 - CN00000022 - M4C2 - CUP D43C22001350001 – 2022

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research on this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Alessandro Ceppi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, software, Supervision, Formal analysis, Data Curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Mohammed Achite: Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Abderrezak Kamel Toubal: Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Tommaso Caloiero: Investigation, software, Formal analysis, Data Curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ceppi, A., Achite, M., Toubal, A.K. et al. Mapping drought characteristics in northern Algerian Basins using the ERA5-Land dataset. Sci Rep 15, 10720 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95418-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95418-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

North Atlantic Oscillation modulation of drought and vegetation activity in Türkiye

Theoretical and Applied Climatology (2026)

-

Evaluation of temporal convolutional networks and ensemble machine learning models for meteorological drought prediction in the Nigerian Sudano–Sahelian zone

Discover Environment (2025)

-

Multi-scale analysis of drought events in Northern Algeria based on ERA5-Land SPI data

Euro-Mediterranean Journal for Environmental Integration (2025)

-

Species Diversity and Distribution Patterns of Riparian Plant Communities: Watershed Scale Study in Northeastern Algeria

Wetlands (2025)