Abstract

Acrylamide (ACR), a neurotoxin typically present in thermally processed foods, is a substantial risk to people. The objective of this research is to develop synbiotic capsules with natural substances such as chitosan, alginate, and L. fermentum. Encapsulation is a significant tool in medicine, helping to improve targeted medication delivery and bioavailability. The chitosan/alginate-encapsulated probiotic (CAP) beads increase the bioavailability of probiotics in the gut, allowing for a more effective response to ACR-induced toxicity. The combination of prebiotic and probiotic activity improves stability, viability, and gastrointestinal delivery. We developed CAP beads and assessed their survivability under simulated gastrointestinal conditions, encapsulating efficiency, and release profile. The efficacy of these beads in reducing the harmful effects of ACR was subsequently investigated using a Drosophila melanogaster model. Under co-exposure and pre-treatment settings, in vivo studies revealed restoration of locomotor activities, redox balance, and ovarian mitochondrial membrane potential in flies treated with CAP beads. Furthermore, implying the indirect impact of CAP beads on gut microbiota and xenobiotic metabolism, pre-treatment with CAP more successfully restored the expression of important antioxidant and stress-related genes, including sod, cat, InR, rpr, and p53.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gut health and microbiota have garnered significant attention in recent years due to their critical roles in maintaining overall health and preventing various diseases. Increasingly, gut microbiota dysbiosis, the imbalance between beneficial and harmful microorganisms in the gut, is being linked to a range of conditions, including metabolic disorders, autoimmune diseases, and hormonal imbalances, particularly among women1. These diseases are influenced by multiple factors, including poor dietary choices, sedentary lifestyles, and disrupted sleep patterns. However, the impact of these factors on gut health is often underestimated. This imbalance can severely affect the gut’s protective functions and overall homeostasis. Eubiosis, or the balanced state of the gut microbiota, plays a vital role in maintaining gut health. The balance between commensal and pathogenic microbes in the gut ensures the proper functioning of the intestinal barrier and supports metabolic processes2.

In addition to actively synthesising important neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine, the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) serves as a protective barrier, a connection between the brain and the immune system3. Any modifications in the gut microbiota often lead to gut dysbiosis, which activates inflammatory processes, generates lipopolysaccharide (LPS), modifies the synthesis of other beneficial metabolites including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), and alters the microbial metabolism2,4,5. Maintaining a normal intestinal microbiota is essential to guarantee sustainable homeostasis considering the complex interaction of the gut with the brain and the immune system.

Our diet is among the most disregarded and typical causes of intestinal irritants. Heat-processed contaminants (HPCs) like acrylamide (ACR) are frequently present in everyday foods like meat and fried potatoes after being subjected to high temperatures. The Maillard reaction—a chemical interaction between amino acids and reducing sugars during high-temperature cooking—forms ACR6. Although ACR is well recognised as a probable carcinogen, it is difficult to completely avoid dietary exposure, even in nations like the United States and the European Union where regulation limitations are in place. Developing countries, however, may lack proper knowledge of ACR’s risks7,8. Given its widespread occurrence and potential health risks, understanding ACR’s impact on human physiology is crucial.

ACR exposure has been linked to several adverse health effects, including neurotoxicity, carcinogenicity, and reproductive toxicity. It is classified as a potential carcinogen and has been shown to cause peripheral neuropathy, muscle weakness, and cognitive decline, particularly in occupational settings9,10. Animal studies have demonstrated a wide range of toxic effects from ACR, including DNA damage, chromosomal aberrations, and retinal damage11,12,13. ACR exposure also negatively affects the gut by disrupting the gut-brain axis, damaging the intestinal barrier, and altering bile acid metabolism14,15,16. These effects contribute to increased levels of cholic acid and a weakened intestinal barrier, further exacerbating ACR’s toxic impact. The gut microbiota also has an important role in modulating ACR-induced toxicity. Investigations on ACR reveal that it disturbs gut flora, changes its composition, and causes systemic inflammation, thereby stressing the need to know how ACR affects gut health15,17,18.

Given the major influence of ACR on intestinal health and general well-being, finding strategies to minimise its negative consequences is attracting increasing attention. Probiotics, particularly those encapsulated in synbiotic formulations, have shown the potential to improve gut health and guard against toxins19,20. Synbiotics are probiotics that have been combined with beneficial fibres such as chitosan and alginate to improve their stability, viability, and effectiveness. Extensive in vitro research on these formulations has revealed their ability to change gut flora composition and increase the synthesis of beneficial metabolites such as SCFAs21,22,23. Synbiotics studies (in vivo), particularly against those associated with food toxins such as ACR, have not been adequately investigated, nevertheless.

This research intends to assess the protective properties of a synbiotic formulation encapsulating Lactobacillus fermentum (recently reclassified as Limosilactobacillus fermentum) in chitosan (CS) and alginate (AL) beads against ACR-induced toxicity using the fruit fly model. L. fermentum, which has been shown to improve gut health and protect against oxidative stress, was chosen for encapsulation24. Due to its genetic resemblance to humans and short lifetime, the fruit fly model is a perfect tool for investigating the consequences of toxins and dietary contaminants. Through this work, we hope to explore the possibilities of synbiotic capsules to enhance gut health and reduce ACR toxicity25,26.

Results

Standardization of alginate concentration with 1% CS

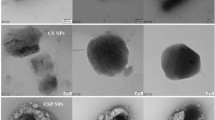

Chitosan-alginate (CS/AL) beads were fabricated and their respective size and morphology were analysed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM). The resultant data demonstrated that CS/AL beads prepared using 1 and 1.5% alginate (AL) in combination with 1% CS formed into irregularly shaped particles with sizes 1.621 and 1.746 mm respectively. Similarly, 2% and 2.5% CS/AL beads formed spherical beads with sizes 1.689 and 2.045 mm respectively. We noticed an increase in bead size and spherification with the rise in AL concentration as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Subsequently, the storage viability and encapsulation efficiency of these chitosan-alginate probiotic (CAP) beads were observed as illustrated in Fig. 2. The storage viability of 1 and 1.5% drastically decreased from 7.31 to 5.90 log CFU/ml and 7.89 to 7.11 log CFU/ml respectively over 28 days (Fig. 2A). A similar mild decrease was observed in 2% CAP beads where day 0 exhibited 8.08 log CFU/ml and 28th day exhibited 7.74 log CFU/ml however, rather stable storage viability was observed in 2.5% CS/AL beads as observed by initial viability of 8.49 to 8.03 log CFU/ml on day 28. Additionally, the encapsulation study (Fig. 2B) demonstrated a significant rise in viable probiotic load post-encapsulation process with an increase in alginate concentration. The 2.5% CAP bead showed a 93.89% encapsulation viability whereas 1, 1.5 and 2% exhibited viability of 69.25%, 76.5%, and 84.1% respectively.

Viability and encapsulation efficiency. The probiotic culture was encapsulated using 1 to 2.5% CS/AL formulations to fabricate chitosan-alginate-coated probiotic (CAP) beads. The storage viability (A) over 28 days and the encapsulation efficiency (B) was assessed. *** and **** demonstrate the significant changes between target groups as p < 0.001 and p < 0.0001, respectively.

These profiles revealed the direct correlation between alginate concentration and encapsulation load. The 2.5% CA/AL combination offered better structural stability than other alginate ratios, as evidenced by high encapsulation efficiency and storage viability on day 28. Additionally, to confirm these aspects, we performed SEM imaging for the chitosan-alginate probiotic (CAP) beads. We noticed a significant increase in size between 1 and 2.5% alginate ratios as follows – 1.77 mm, 1.894 mm, 1.959 mm, and 2.262 mm respectively as shown in Fig. 3. Our extended investigations with variations of probiotic load (8 log CFU/ml) within a 2.5% CS/AL shell yielded particles ranging from 3 to 4 mm spheres. However, constraining in the microcapsule size range of 50 nm to 2 mm, the present study reports the fabrication of ~ 2.2–2.3 mm CAP beads with a 1:2.5% (CS: AL) encapsulant ratio and an encapsulated probiotic load of 7.69 log CFU/ml (3 ml; 5 × 107 CFU/ml) for therapeutic applications as dietary supplements.

Release profile and viability under simulated conditions

Based on the standardization results, we deduced the efficiency and stability of 2.5% CAP beads, therefore we further investigated the release profile of the synbiotic formulation for 6 h. As depicted in Fig. 4, The probiotic release rate at the beginning of incubation [0 h] = 45.56%. There was a gradual increase in the release rate; at the 5th and 6th hour, the release efficiency was 59.88% and 77.8%, respectively. From these data, we postulate that initially, the release rate of 45.56% at 0 h may indicate that a substantial portion of the probiotics is readily available at the start of incubation at slightly acidic pH, which could be beneficial for ensuring an immediate therapeutic effect or rapid colonization in the target environment. The gradual increase in release rate, reaching 77.8% by the 6th hour, shows a controlled and sustained release mechanism in the pH 6.5 citrate buffer at room temperature.

As depicted in Fig. 5, with the increased exposure time in SGF, the viability of the non-encapsulated (free) culture significantly decreased from 10.67 to 6.18 log CFU/ml whereas, the encapsulated probiotics showed a gradual decrease from 10.18 to 8.41 log CFU/ml. Similarly, with the increased exposure in SIF, the viability of the non-encapsulated culture significantly decreased from 9.90 to 6.34 log CFU/ml whereas, the encapsulated culture showed a gradual decrease from 9.85 to 8.58 log CFU/ml.

CAP restores ACR-induced lifespan and locomotor deficits

The baseline groups such as control (53 days; 99.25%; 68.47 mm/min), CS/AL (57 days; 98.51%; 54.33 mm/min) and probiotics (58 days; 98.88%; 65.07 mm/min) exhibited a normal lifespan and locomotor functioning. In contrast, ACR-treated flies exhibited a low survival rate with an average life span of 12 days and reduced larval and fly behavioural traits (30.3 mm/min and 86.76%) as depicted in Fig. 6. In comparison, our pre- and co-exposure treatment demonstrated prominent behavioural activity and lifespan. This indicates the 14 days of CAP pretreatment before 5 days of ACR exposure (46 days; 94.8%; 65.6 mm/min) and 5 days of CAP co-exposure with ACR (44 days; 99.25%; 61.88 mm/min) demonstrated similar protective effects against ACR toxicity. Overall, the flies treated with CAP beads exhibited a neutralizing effect against ACR in both exposure methods albeit with varying exposure periods.

CAP regulates ACR-induced ROS and GST levels

As observed in Fig. 7, reactive oxygen species, the commonly known redox stress marker were markedly increased in ACR-treated flies with subsequent increase in the GST activity. In contrast, the baseline groups such as control, probiotics, and CS/AL demonstrated normalised ROS and relatively low GST activity. Therefore, comparing all these datasets with pre-and co-exposure data it can be determined that CAP exposure in general maintains the ROS and GST levels at near normal range even in the presence of ACR thereby indicating strong protective effects of the synbiotic formulation at a cellular level.

CAP rescues ACR-induced developmental deficits

Figure 8 reveals the negative impact of ACR on fly fertility whereas the treatment sets PT-CAP—ACR and ACR + CAP demonstrated a normalised fecundity rate compared to control. Though, we noticed a slight decrease in the PT-CAP—ACR group it did not impact the fertility as significantly as noted in the ACR treatment set. The egg-to-adult development rate was significantly low in the ACR treatment groups (30.7%) however the pre/co-exposure groups exhibited 79.25% and 88.51% respectively. Overall, ACR affected the fertility and development of the fruit fly model whereas CAP exposure protected against ACR-induced impact and maintained the stability of the developmental mechanisms.

CAP restores ovarian mitochondrial membrane potential following ACR exposure

As illustrated in Fig. 9, the TMRE intensity is relatively high in both PT-CAP—ACR and ACR + CAP treatments compared to the ACR groups. These high levels of TMRE signal in Drosophila ovaries indicate healthy mitochondria and optimal energy production, which is crucial for egg development and ovarian function. However, a decrease in TMRE staining after ACR exposure suggests mitochondrial damage or dysfunction, indicating oxidative stress or cellular damage in the ovaries. Furthermore, ACR treatment increased DCF-DA fluorescence whereas CAP maintained basal levels as observed in control groups, which indicates that ACR is generating high levels of ROS in the ovarian cells. This rise in ROS levels could lead to oxidative damage in the mitochondria, proteins, and DNA, potentially affecting fertility and ovarian function as noted in the TMRE and developmental datasets. Overall, CAP exposure maintained a stable intensity comparable to the data observed in the control population indicating the flies pre- or co-exposed to CAP did not experience any ROS accumulation or mitochondrial dysfunction when exposed to ACR.

CAP modulates stress response genes in D.mel ovaries

Based on the developmental profile observed at the cellular level, we further analysed the expression of stress response genes in the ovaries. As illustrated in Fig. 10, ACR-treated files demonstrated the downregulation of sod and InR genes whereas cat, rpr and p53 expressions were upregulated. Subsequently, CAP pre- and co-exposure maintained a stable expression of sod, InR and rpr genes. Whereas, a mild upregulation of cat and p53 was noticed in the ACR + CAP population.

Discussion

Acrylamide (ACR), a probable carcinogen present in industrial processes, is predominantly consumed through deep-fried meals and offers a serious health risk, particularly to children27. The present study investigates the use of stable chitosan/alginate-encapsulated L. fermentum beads (2.3–4 mm) to improve probiotic stability and bioactivity against ACR toxicity. The initial standardisation indicated differences in bead size and shape depending on alginate concentration. Although widely used for encapsulation, alginate proved to be weak and prone to dehydration, hence low molecular weight chitosan was added to increase stability. The developed chitosan/alginate beads guaranteed a prolonged, regulated probiotic release. The release profile and simulated gastrointestinal (GI) tests revealed a regulated, sustained release of probiotics in slightly acidic/basic environments, which is critical for sustaining viability and efficacy in the GI tract. Under simulated GI circumstances, free probiotics displayed a 1.5 to 1.75-fold loss in viability; encapsulated probiotics displayed a slower drop (1.1 to 1.21-fold). This suggests that encapsulation offers a protective layer that lets more probiotics survive in demanding environments and get to their designated location of action.

To the best of our knowledge, no research has looked into synbiotic capsules against ACR employing the fruit fly model. In this work, we evaluated the effects of synbiotic beads on fruit fly gut microbiota and their capacity to reduce ACR toxicity via pre-treatment and co-treatment approaches. Whereas the pre-treatment paradigm (14 days of synbiotics followed by 5 days of ACR exposure) concentrated on enhancing the gut’s resistance mechanisms, the co-exposure model (5-day treatment) helped assess the direct protective benefits of the synbiotics against ACR. Any physiological or biochemical recovery after ACR exposure in the pre-treatment model can be attributed to synbiotic-mediated detoxification mechanisms.

Our survival and behavioural analysis showed that CAP treatment helped maintain neuromuscular function and lifespan in flies, highlighting its protective effects against ACR-induced toxicity. This was consistent in both pre- and co-exposure models, suggesting that synbiotic beads influence gut microbiota and enhance the fly’s defence mechanisms against ACR. This finding aligns with previous studies showing that probiotic treatments can normalize abnormal locomotor behaviour in flies lacking gut microbiota. Further examination into the redox pathways indicated that ACR exposure produced ROS and activated GST, which relates to cytochrome P450 bioactivation and GSH conjugation. GST overexpression helps to reduce oxidative damage and maintain redox homeostasis28. By means of normalising redox levels, CAP exposure also indicate no noteworthy oxidative stress in pre- and co-exposure treatments. This suggests that encapsulated probiotics may protect against ACR in the gut, potentially through physical adsorption29 and metabolization of ACR by probiotics29,30. Another study reported the ability of 14 LAB strains to metabolize acrylamide (5 and 10 mg/mL) was tested in vitro at 37 °C over 0, 4, and 12 h in different pH conditions (3, 5, and 8). The results revealed that acrylamide binding varied depending on pH, acrylamide concentration, strain type, and incubation duration. The binding was discovered to be a quick, passive process that occurs on the bacterial surface, corroborating our prediction31.

During the metamorphosis phase of its developmental cycle, the fruit fly model completely changes and offers the special benefit of evaluating toxicity at two different stages: 3rd instar larvae and adult flies. But its two main life-history features, fecundity and eclosion, define its growth most fundamentally. Fecundity directly shows how xenobiotics affect the fertility of the model and displays the egg-laying capability of the female population. Following the fertility aspect, another vital parameter is demonstrated by the eclosion rate. This indicates the transformation of an egg to an adult fly through larval molting stages and metamorphosis, all in the presence of respective toxic and treatment media32. The detrimental effects of ACR on fecundity and eclosion rates in fruit flies were demonstrated by our findings. Both parameters were substantially modified by ACR exposure; however, the effects were mitigated by pre- and co-treatment with CAP, which preserved reproductive health and developmental progression.

Based on these observations, it appears that CAP may be able to mitigate the adverse effects of ACR, either by circumventing its action or by aiding recovery in organisms that have been exposed to it. It was determined that TMRE and DCF-DA staining of ovaries was necessary in order to validate the developmental toxicity that was generated by ACR and the protective effects of CAP beads. TMRE labelling measured mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), an important biomarker of mitochondrial health33. Reduced MMP in ACR-treated flies points to mitochondrial dysfunction, which could cause ovarian dysfunction and lower fertility. CAP treatment preserved mitochondrial function, potentially mitigating oxidative damage from ACR, which explains the improved fecundity and egg-to-adult development in the PT-CAP—ACR and ACR + CAP groups. Furthermore, DCF-DA staining revealed elevated ROS levels in ACR-treated flies, correlating with reduced MMP. In contrast, CAP treatment maintained normal ROS levels and preserved mitochondrial integrity. Upon oxidation by ROS, DCF-DA is converted into the highly fluorescent DCF (Dichlorofluorescein), which emits green fluorescence and helps us estimate the intracellular ROS levels34. This suggests that CAP protects against oxidative stress, supporting mitochondrial health and reproductive function.

Gene expression analysis further supported these findings. Our understanding of developmental aspects could be drawn from previously established studies where probiotics influence InR expression and alter gut microbiota, innate immunity, systemic Ilps via the gut-brain axis, and control dTOR pathways35,36. Furthermore, sod and cat are major antioxidant enzyme genes and their increased and decreased expressions have been reported to negatively affect the redox balance37,38. ACR treatment downregulated sod and InR, key genes involved in oxidative stress defence and insulin signalling while upregulating cat, rpr, and p53, which indicate increased oxidative stress and apoptosis. In the CAP pre- and co-exposure groups, sod and InR expression remained stable, suggesting that CAP helps preserve antioxidant defences and prevent apoptosis. Mild upregulation of cat and p53 in the ACR + CAP group indicates partial mitigation of oxidative stress by CAP, highlighting its protective role. Furthermore, rpr and p53 genes have a common mode of action in triggering the apoptotic pathways. In the fruit fly model, p53 interacts with apoptotic modulators in the cytosol or mitochondrial membrane along with pro-apoptotic genes like rpr to initiate caspase activity and JNK-mediated signalling. Therefore, in an unstressed state, the p53 levels are maintained low with the help of MDM2 (ubiquitin ligase), similarly, low levels were noted in CAP treatment groups suggesting strong suppression of ACR influence especially in the pre-treatment model39. Overall, our study suggests that the gut microbiota plays a critical role in mitigating ACR-induced toxicity in the fruit fly model. Previous research has demonstrated that probiotics affect oxidative stress, immunological responses, and signalling pathways, notably through the gut-brain axis and dTOR pathways. The effects that were seen on gene expression and antioxidant levels are consistent with these findings. Particularly in the pre-treatment model, CAP therapy normalises gene expression, therefore supporting ovarian function and preventing damage induced by ACR.

Building on the positive results of CAP beads in the fruit fly model, it is essential to understand the differences between commercially available probiotic and synbiotic formulations. The origin of strains and CFU counts are often kept confidential as trade secrets, so we compiled relevant literature on these products. The studies by Naissinger da Silva. et al. (2021)40 and Stasiak-Różańska et al. (2021)41 offer valuable insights into the viability and resilience of commercial probiotic and synbiotic formulations (capsules and lyophilised powder). These investigations reveal key findings about how different formulations perform under simulated gastrointestinal conditions, a critical factor in determining their effectiveness once consumed. The study by Naissinger da Silva et al., 2021 found that industrial probiotics (IP) and synbiotic formulations (containing both probiotics and prebiotics) displayed high initial probiotic concentrations (8–10 log CFU/g). These formulations maintained good viability after digestion (~ 7 log CFU/g), suggesting that they are likely to reach the intestines in sufficient quantities to exert health benefits40.

Stasiak-Różańska et al. 2021 investigated the effectiveness of probiotic strains in a food matrix under analogous conditions. Especially significant is their discovery that Lactobacillus plantarum displayed the best resistance in both intestinal and stomach conditions. Even when supplemented with prebiotics such as fructooligosaccharides (FOS) and inulin, this strain was able to endure these circumstances, which implies that it may be more efficient than other strains that were less resistant to the conditions41. This emphasises the need for strain-specific responses in probiotic formulations as not every strain performs exactly in terms of survival. Research from all across the world, including the Philippines, South Korea, the United States, and Canada, stress the need to make sure probiotic products satisfy regulatory criteria for viability during their shelf life and following digestion. For customer confidence and the therapeutic value of probiotics—many products lose viability over time—this consistency is essential. Products must offer their desired health effects by means of suitable probiotic concentrations both during ingestion and following digestion42,43.

Ultimately, we encapsulated 3 ml of L. fermentum by developing synbiotic beads from 2.5% alginate mixed with 1% low molecular-weight chitosan. These beads presented a prolonged release profile, good encapsulating efficiency, and persistent survival under simulated gastrointestinal circumstances. Using pre-treatment and co-exposure models, we also assessed the protective properties of the synbiotic beads against acrylamide (ACR), thereby essentially normalising behavioural, biochemical, and developmental processes in flies and shielding them from ACR-induced impairments. Particularly in the pre-treatment model, the seen advantages point to a possible gut-mediated xenobiotic resistance mechanism. Although our work offers a comprehensive examination of the in vivo impacts, more sophisticated models of research are required before human applicability is discussed. Furthermore, numerous probiotic supplements are commercially accessible; however, our synbiotics have a mono-strain formulation with bilayer biopolymer coating, a prolonged release profile, shelf stability, a high probiotic load, and the usage of heterofermentative probiotic strains. Designed to be as appealing and practical as trendy candy and boba pearls, we hope to use this formulation into food products like jelly, puddings, milkshakes, and cold drinks.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and probiotic culture

Low molecular weight chitosan (34.5 m Pas, 90.1% degree of deacetylation, ~ 50 kDa), Acrylamide, Agar Agar Type-I, Glacial acetic acid, DCFH-DA, DTNB, Dextrose, Orthophosphoric Acid, Sodium alginate, Propionic Acid, Sodium phosphate monobasic, Sodium citrate, Sodium phosphate dibasic, Abcam TMRE-Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Assay Kit, NADH, Yeast Extract, Acetylcholine iodide, Methylparaben, Pepsin, was procured from Sisco Research Laboratories, India. Schneider’s insect medium, Pancreatin, Bile salt, etc. were procured from Himedia Pvt. Ltd, India. All chemicals purchased were analytical grade. L. fermentum (MCC 2760) stock was obtained from NCCS, Pune and stored at -20 ℃. The activated cultures were maintained by periodical subcultures in MRS broth (pH 6.5) at 37 °C.

Fabrication and characterization of chitosan alginate probiotic (CAP) beads

The chitosan alginate probiotic (CAP) beads were fabricated by loading freshly cultured L. fermentum culture (7.69 log CFU/ml) into alginate/chitosan capsules. The present study follows the previously reported ionic-gelation encapsulation method with moderate alterations in alginate (AL) concentration to ensure stability and encapsulation efficiency. Initially, alginate concentrations of 1-2.5% were used to produce stable spherical capsulates to achieve enhanced stability and encapsulation efficiency of the probiotic load. Briefly, 3 ml of the probiotic culture was mixed with alginate and stirred using a magnetic stirrer for 15 min at 200 rpm. This mixture was later loaded into a 5 ml syringe and slowly extruded into the chitosan mixture (1% low molecular weight chitosan (CS) and 1.5% calcium chloride) with constant stirring at 290 rpm for 30 min. The extruded beads were then thoroughly washed thrice for 15 min using distilled water, dried and stored in a sterile container at 4 ℃ for experimental analysis44. The CAP beads morphology and size were then determined using a Hi-Resolution scanning electron microscope, Thermo Scientific Apreo S, USA.

Viability and release profile

The synthesized CAP beads were assessed for storage viability, encapsulation/release efficiency and viability under simulated gastrointestinal (GI) conditions to ensure the stability of the capsules as well as the viability of the encapsulated probiotic load45. The storage stability was estimated by dissolving 1 g of the stored synbiotic beads in 1% sodium citrate (pH 6.5) every 7 days for 28 days. The suspension was then plated on MRS agar plates to determine the bacterial colonies formed (log CFU/ml) to establish the viability of the encapsulated probiotics.

Furthermore, the encapsulation efficiency determines the probiotic survival rate post the encapsulation process. This was assessed by suspending the beads in citrate buffer followed by bacterial colony enumeration in comparison to the free culture. The difference in CFU/ml between free and encapsulated samples was reported as encapsulation rate (%). Similarly, the release profile was analysed by plating the bead suspension onto MRS agar plates every 2 h for 6 h (mimicking the GI tract release profile) and incubated overnight at 37 ℃. This data was compared with free probiotic culture and the profile was demonstrated as release rate (%).

The viability of the synbiotic beads under simulated GI conditions was analysed by suspending 1 g of CAP beads in simulated gastric fluid (SGF) comprised of 3 mg/ml pepsin; pH 2 adjusted with 1 M HCl. The suspension was kept on a magnetic stirrer and constantly stirred at 250 rpm. 1 ml aliquots of the suspension was plated on MRS agar plates at 0, 60, 120 and 180 min. The plates were then incubated at 37 ℃ for 24 h and the bacterial colonies were enumerated as log CFU/ml. The beads were transferred to simulated intestinal fluid (SIF) (3 mg/ml pancreatin and 1% bile salt; pH 8) and the log CFU/ml was estimated at 0, 60, 120, and 180 min45.

Drosophila handling and exposure paradigm

The in vivo experiments were studied using the wild-type Oregon K strain of the fruit fly model. The fly stocks were reared on a cornmeal agar enriched with dextrose and yeast at 25 ± 2 ℃ with 65% relative humidity. For experimental purposes, stoichiometric measures of acrylamide (ACR) or probiotics were added to the cornmeal agar as per suitability. Additionally, antifungal compounds like orthophosphoric and propionic acids were mixed into the media at 55–58 ℃. The in vivo toxicity analysis was conducted by exposing the fruit flies to respective treatment media accordingly. The present study was investigated using the following treatment groups – control, 2 mM ACR, probiotics (3 ml of L. fermentum broth), chitosan-alginate beads without probiotic load (CS/AL), co-treatment of ACR and 1 g CAP beads (ACR + CAP) and 1 g CAP pretreatment and ACR exposure (PT-CAP—ACR). Assessment of CAP beads against ACR-induced toxicity was conducted by co-exposure and pre-treatment model, wherein, in the co-exposure study, the flies were simultaneously exposed to CAP and ACR mixed in the cornmeal agar for 5 days. Whereas, in the pre-treatment model, the flies were exposed to CAP-treated cornmeal agar for 14 days then transferred to ACR media and incubated for 5 days. For experiments involving fruit flies, the beads were mixed with standard fly media to enable the gradual release of probiotics into the environment. This setup ensured that the flies were exposed to the probiotics over a sustained period, simulating prolonged delivery. The experimental design aimed to validate the probiotic encapsulation system’s functionality in a model organism while ultimately targeting therapeutic applications for human use. All the experiments were performed in triplicates to ensure statistical significance.

Survival and behavioural profile

The survival and behavioural parameters are essential toxicity indicators in the fruit fly model as they are intricately linked to environmental cues and neuromuscular functioning. The survival experiment demonstrates the influence of treatment compounds on the lifespan under the chronic exposure paradigm. Here, 30 newborn male flies were transferred to respective control and treatment media and the fly mortality count was recorded every 24 h. Additionally, the locomotor functioning of flies is assessed at two developmental stages – 3rd instar larvae and adult flies. The larval locomotor function is computed by allowing a 3rd instar larva to crawl on a 2% agar plate placed on a graph sheet. The distance crawled in a minute was directly equated to the number of 1 mm grids crossed by the larvae. The adult fly behaviour is characterised by its innate escape response – climbing activity also often referred to as negative geotaxis behaviour. 30 male flies exposed to the respective treatment sets are transferred to empty 10 cm vials. The vials were tapped and the number of active flies above the 3 cm mark was recorded for statistical analysis27.

Estimation of redox stress markers

The present study analysed the reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels and glutathione-s-transferase (GST) activity, a major phase II detoxification enzyme. Following a previously reported study27,46, 30 male flies post respective treatments were homogenised in Tris and sodium phosphate buffer and the subsequent supernatants were collected and stored at − 20 ℃ for further analysis. 100 µl of homogenates were mixed with respective reagents in stoichiometric measures and the respective readings were recorded for statistical analysis.

Fecundity and eclosion profile

The fecundity and eclosion rate in fruit fly studies indicate the egg-laying capacity of females and the subsequent hatching of adult flies from the eggs respectively. the developmental stages are assessed by following the protocol reported by PB et al., 202047, ten male and female flies were allowed to mate for 48 hours under specific treatment conditions. The flies were then transferred to fresh vials every 24 h to measure fecundity by counting the eggs laid. Additionally, ten eggs per treatment vial were collected and placed in fresh vials (n = 3) to develop into adults. The number of eclosed flies was counted to calculate the egg-to-adult development ratio, expressed as a percentage.

Estimation of ovarian mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP)

Thirty female flies were subjected to control and treatment medium, and their ovaries were dissected to determine mitochondrial membrane potential. The procedure was based on the Abcam TMRE-Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Kit. The ovaries were dissected in Schneider’s insect media, stained with 200 nM TMRE for 15 min in the dark, rinsed in PBS, and viewed using a Leica DM6 fluorescent microscope.

Gene expression analysis

The gene expression analysis was performed following kit-based protocols reported by Senthilkumar et al., 202027. Briefly, 50 pairs of ovaries were homogenised and RNA was isolated following the TRIzol method, the RNA was then converted to cDNA and utilised for subsequent qPCR analysis. The cycle conditions were set based on the kit method for 35 cycles. The primer sequences for all the genes used for this experiment are listed in Table 1.

Statistical analysis

Experiments in this study were all performed in triplicates to achieve statistically significant results. Data are reported as mean ± SEM unless indicated otherwise. Statistical analysis was conducted with Graph Pad Prism 6.0 software, using Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests to assess the significance of differences between treatment groups, control, and ACR. The alpha level of significance for the analysis was set at p < 0.05 whereas, statistical significance between treatment groups, **** demonstrates p < 0.0001, *** demonstrates p < 0.001, ** demonstrates p < 0.01 and * demonstrates p < 0.05, respectively. The symbols * and # indicate the comparison significance of specific treatment with the control or ACR group, respectively.

Data availability

All data sets used and/or generated in this work are obtainable from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Quigley, E. M. M. Microbiota-brain-gut axis and neurodegenerative diseases. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 17, (2017).

Kasarello, K., Cudnoch-Jedrzejewska, A. & Czarzasta, K. Communication of gut microbiota and brain via immune and neuroendocrine signaling. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1118529 (2023).

Silva, Y. P., Bernardi, A. & Frozza, R. L. The role of short-chain fatty acids from gut microbiota in gut-Brain communication. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 11, 25 (2020).

Thursby, E. & Juge, N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochem. J. 474, 1823 (2017).

Lerner, A., Neidhöfer, S. & Matthias, T. The gut microbiome feelings of the brain: A perspective for non-microbiologists. Microorganisms 5 (2017).

Mogol, B. A. & Gökmen, V. Thermal process contaminants: acrylamide, chloropropanols and Furan. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 7, 86–92 (2016).

Scientific Opinion on acrylamide in food. EFSA J. 13, (2015).

Survey Data on Acrylamide in Food | FDA. https://www.fda.gov/food/process-contaminants-food/survey-data-acrylamide-food

Spencer, P. S. & Schaumburg, H. H. Nervous system degeneration produced by acrylamide monomer. Environ. Health Perspect. 11, 129 (1975).

Lindeman, B. et al. Does the food processing contaminant acrylamide cause developmental neurotoxicity? A review and identification of knowledge gaps. Reprod. Toxicol. 101, 93–114 (2021).

Huang, Z. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction promotes the necroptosis of purkinje cells in the cerebellum of acrylamide-exposed rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 171, 113522 (2023).

Yilmaz, B. O., Yildizbayrak, N., Aydin, Y. & Erkan, M. Evidence of acrylamide- and glycidamide-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in Leydig and Sertoli cells. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 36, 1225–1235 (2017).

Albalawi, A. et al. Carnosic acid attenuates acrylamide-induced retinal toxicity in zebrafish embryos. Exp. Eye Res. 175, 103–114 (2018).

Tan, X. et al. Acrylamide aggravates cognitive deficits at night period via the gut–brain axis by reprogramming the brain circadian clock. Arch. Toxicol. 93, 467–486 (2019).

Yue, Z. et al. Acrylamide induced glucose metabolism disorder in rats involves gut microbiota dysbiosis and changed bile acids metabolism. Food Res. Int. 157, 111405 (2022).

Muszyński, S. et al. Maternal acrylamide exposure changes intestinal epithelium, immunolocalization of leptin and ghrelin and their receptors, and gut barrier in weaned offspring. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–16 (2023).

Amirshahrokhi, K. Acrylamide exposure aggravates the development of ulcerative colitis in mice through activation of NF-κB, inflammatory cytokines, iNOS, and oxidative stress. Iran. J. Basic. Med. Sci. 24, 312 (2021).

Brownlee, I. A., Uranga, J. A. & Palus, K. Dietary exposure to acrylamide has negative effects on the gastrointestinal tract: A review. Nutrients. 16, 2032 (2024).

Maher, A., Miśkiewicz, K., Rosicka-Kaczmarek, J. & Nowak, A. Detoxification of acrylamide by potentially probiotic strains of lactic acid bacteria and yeast. Molecules 29, 4922 (2024).

Bauer-Estrada, K., Sandoval-Cuellar, C., Rojas-Muñoz, Y. & Quintanilla-Carvajal, M. X. The modulatory effect of encapsulated bioactives and probiotics on gut microbiota: improving health status through functional food. Food Funct. 14, 32–55 (2023).

Golnari, M., Behbahani, M. & Mohabatkar, H. Comparative survival study of Bacillus coagulans and Enterococcus faecium microencapsulated in chitosan-alginate nanoparticles in simulated Gastrointestinal condition. LWT 197, 115930 (2024).

Masoomi Dezfooli, S., Bonnot, C., Gutierrez-Maddox, N., Alfaro, A. C. & Seyfoddin, A. Chitosan coated alginate beads as probiotic delivery system for new Zealand black footed abalone (Haliotis iris). J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 139, (2022).

Gunasangkaran, G., Ravi, A. K., Arumugam, V. A. & Muthukrishnan, S. Preparation, characterization, and anticancer efficacy of chitosan, chitosan encapsulated piperine and probiotics (Lactobacillus plantarum (MTCC-1407), and Lactobacillus rhamnosus (MTCC-1423) nanoparticles. Bionanoscience 12, 527–539 (2022).

Zhao, Y. et al. Lactobacillus fermentum and its potential Immunomodulatory properties. J. Funct. Foods. 56, 21–32 (2019).

Capo, F., Wilson, A. & Di Cara, F. The Intestine of Drosophila melanogaster: An emerging versatile model system to study intestinal epithelial homeostasis and host-microbial interactions in humans. Microorganisms. 7, (2019).

Jia, Y. et al. Gut microbiome modulates Drosophila aggression through octopamine signaling. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–12 (2021).

Senthilkumar, S. et al. Developmental and behavioural toxicity induced by acrylamide exposure and amelioration using phytochemicals in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Hazard. Mater. 394, 122533 (2020).

Sen, A., Ozgun, O., Arinç, E. & Arslan, S. Diverse action of acrylamide on cytochrome P450 and glutathione S-transferase isozyme activities, mRNA levels and protein levels in human hepatocarcinoma cells. Cell. Biol. Toxicol. 28, 175–186 (2012).

Khorshidian, N. et al. Using probiotics for mitigation of acrylamide in food products: a mini review. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 32, 67–75 (2020).

Petka, K., Sroka, P. & Tarko, T. & Duda-Chodak, A. The acrylamide degradation by probiotic strain Lactobacillus acidophilus LA-5. Foods 11, (2022).

Serrano-Niño, J. C. et al. In vitro reduced availability of aflatoxin B1 and acrylamide by bonding interactions with teichoic acids from Lactobacillus strains. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 64, 1334–1341 (2015).

Senthil Kumar, S. & Sheik Mohideen, S. Chitosan-coated probiotic nanoparticles mitigate acrylamide-induced toxicity in the Drosophila model. Sci. Rep. 14, 1–13 (2024).

Deng, H., Takashima, S., Paul, M., Guo, M. & Hartenstein, V. Mitochondrial dynamics regulates drosophila intestinal stem cell differentiation. Cell. Death Discov. 4, 81 (2018).

Myers, A. L., Harris, C. M., Choe, K. M. & Brennan, C. A. Inflammatory production of reactive oxygen species by drosophila hemocytes activates cellular immune defenses. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 505, 726 (2018).

Westfall, S., Lomis, N. & Prakash, S. Ferulic acid produced by Lactobacillus fermentum influences developmental growth through a dTOR-Mediated mechanism. Mol. Biotechnol. 61, 0 (2019).

Mularczyk, M., Bourebaba, Y., Kowalczuk, A., Marycz, K. & Bourebaba, L. Probiotics-rich emulsion improves insulin signalling in Palmitate/Oleate-challenged human hepatocarcinoma cells through the modulation of Fetuin-A/TLR4-JNK-NF-κB pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 139, 111560 (2021).

Blackney, M. J., Cox, R., Shepherd, D. & Parker, J. D. Cloning and expression analysis of drosophila extracellular Cu Zn superoxide dismutase. Biosci. Rep. 34, 851–863 (2014).

Sim, C. & Denlinger, D. L. Catalase and superoxide dismutase-2 enhance survival and protect ovaries during overwintering diapause in the mosquito culex pipiens. J. Insect Physiol. 57, 628–634 (2011).

Ingaramo, M. C., Sánchez, J. A. & Dekanty, A. Regulation and function of p53: A perspective from drosophila studies. Mech. Dev. 154, 82–90 (2018).

Naissinger da Silva, M., Tagliapietra, B. L. & Flores, V. D. A. & Pereira dos Santos Richards, N. S. In vitro test to evaluate survival in the gastrointestinal tract of commercial probiotics. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 4, 320–325 (2021).

Stasiak-Różańska, L., Berthold-Pluta, A., Pluta, A. S., Dasiewicz, K. & Garbowska, M. Effect of simulated gastrointestinal tract conditions on survivability of probiotic bacteria present in commercial preparations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 1–17 (2021).

Dioso, C. M. et al. Do your kids get what you paid for? Evaluation of commercially available probiotic products intended for children in the Republic of the Philippines and the Republic of Korea. Foods 9, (2020).

Shehata, H. R. & Newmaster, S. G. Combined targeted and Non-targeted PCR based methods reveal high levels of compliance in probiotic products sold as dietary supplements in united States and Canada. Front. Microbiol. 11, 531086 (2020).

Djaenudin, Budianto, E., Saepudin, E. & Nasir, M. The encapsulation of Lactobacillus casei probiotic bacteria based on sodium alginate and Chitosan. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 483, (2020).

Khosravi Zanjani, M. A., Tarzi, B. G., Sharifan, A. & Mohammadi, N. Microencapsulation of probiotics by calcium alginate-gelatinized starch with chitosan coating and evaluation of survival in simulated human gastro-intestinal condition. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 13, 843 (2014).

Siddique, Y. H. et al. Toxic potential of copper-doped ZnO nanoparticles in Drosophila melanogaster (Oregon R). Toxicol. Mech. Methods. 25, 425–432 (2015).

PB, B. et al. Prophylactic efficacy of Boerhavia diffusa L. aqueous extract in toluene induced reproductive and developmental toxicity in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Infect. Public. Health. 13, 177–185 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the SRM SCIF and DBT platform for Advanced Life Science’s support in SEM, fluorescence imaging studies and real-time qPCR analysis. The authors also recognise the support provided by the Department of Science and Technology, Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India through the INSPIRE Fellowship program (No. DST/INSPIRE Fellowship/2021/IF210062).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SS – Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Software, Validation; SSM –Conceptualization, Funding Acquisition, Methodology, Validation, Writing - review & editing and Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors Sahabudeen Sheik Mohideen and Swetha Senthil Kumar disclose their role as inventors on a published patent (Indian Patent application No. – 202441050471), titled – “A FORMULATION AGAINST ACRYLAMIDE TOXICITY AND A METHOD OF PREPARATION THEREOF”, which is assigned to SRM Institute of Science and Technology, Kattankulathur and is currently pending examination. The patent application is related to the research presented in this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Senthil Kumar, S., Sheik Mohideen, S. Encapsulation of L. fermentum with chitosan-alginate enhances its bioactivity against acrylamide toxicity in D.mel. Sci Rep 15, 11324 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95499-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95499-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Alginate-based encapsulation: from historical evolution to AI-driven optimization for sustainable innovations

Polymer Bulletin (2026)

-

Probiotics as an Adjunct Ameliorates Ovarian Toxicity in Endotoxemic Mice via Modulating TLR 4/MyD88/NF-κB Signalling Pathway: Insights from In Vivo and In Silico Study

Reproductive Sciences (2025)