Abstract

Previous studies have found a correlation between peer attachment and Internet addiction. The three dimensions (peer trust, peer communication, and peer alienation) of peer attachment reflect different needs in peer relationships. This study used network analysis to construct a network model of the three dimensions of peer attachment and Internet addiction. The primary aim was to identify which peer relationship needs are most significantly associated with Internet addiction in adolescents. A total of 782 adolescents (413 girls and 369 boys, Mean age = 13.52, SD age = 1.17) from school participated in this study. Basic demographic information was obtained through a questionnaire. Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment and Young Internet Addiction Test were used to measure peer attachment and Internet addiction in adolescents. Internet addiction was negatively correlated with the three dimensions of peer attachment: peer trust (r = -0.22), peer communication (r = -0.17), and peer alienation (r = -0.47). Peer trust was the central factor in the network model. Prominent symptoms in the network model included IA2 (“How often do you neglect household chores to spend more time online?”) and IA12 (“How often do you fear that life without the Internet would be boring, empty, and joyless?”). Peer communication acted as a bridge between peer attachment and Internet addiction in the network model. Less trust in peers is associated with a higher risk of becoming addicted to the Internet. Fostering peer trust may encourage adolescents to engage in real-life social activities, thus reducing their reliance on the Internet for social fulfillment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Internet addiction is characterized by excessive or poorly controlled preoccupations, urges or behaviors regarding computer use and Internet access that lead to impairment or distress1. Despite the lack of a universally accepted definition, it is clear that Internet addiction not only modifies the behavioral patterns of individuals but also significantly disrupts their social interactions2. Furthermore, the adverse effects are exacerbated when Internet addiction is comorbid with other mental health issues3. A cross-sectional study of a substantial sample found that 29.9% of adolescents exhibited Internet addiction, with 11.5% engaging in self-injurious behaviors4. Adolescence is a period when individuals typically spend more time with peers at school than with family. Peer relationships play a pivotal role in the development of Internet addiction5. Adolescents who find their attachment needs unmet by real-life peers may turn to online interactions as a form of compensation6,7,8.

Attachment refers to a deep, enduring, and bi-directional emotional bond that forms between individual and specific attachment figures which is characterized by the desire for proximity and safety in times of distress9. Beyond a fleeting emotion, attachment serves as a cornerstone for an individual’s sense of security, capacity for exploration, and emotional development throughout their life span9,10,11. Caregivers (usually the parents) usually serve as the first attachment figures for an individual. The quality of this parental attachment profoundly affects an individual’s sense of security, trust, and self-esteem, which in turn deeply influences their future interpersonal relationships and overall psychological well-being9. As individuals grow up, their attachment figures naturally expand beyond parents to others, such as siblings, peers, and romantic partners. This expansion is grounded in the changing needs and life experiences of the individual11. The extension of attachment figures is not a replacement of earlier bonds but rather an addition to them. Each new attachment figure serves a different function and meets different needs at various stages of life.

According to Attachment Theory, peer attachment refers to the emotional bond and connection that individuals establish with their peers12. This bond serves to satisfy the need for intimacy among individuals. During adolescence, peers emerge as significant attachment figures in an individual’s life. Peers are pivotal for emotional communication and social support13,14. When the attachment needs remain unmet, adolescents may compensate for this lack through other means6,15,16. The Compensatory Internet Use Theory also states that online social interaction serves as a vital compensation for adolescents when their needs are not met in real life17,18. A systematic review found that individuals often turn to online socialization to compensate for the emotional needs that are unmet by their peers in real life19. Empirical studies have demonstrated that enhancing the interpersonal relationships of adolescents with their peers can mitigate the severity of their Internet addiction7,20,21,22. Previous studies investigated the correlation between peer attachment and Internet addiction12,23,24. However, fewer studies have focused on the relationship between the different dimensions of peer attachment and Internet addiction. Peer attachment is composed of three dimensions: (1) peer trust, which is connected to the trust among adolescents that their peers understand and respect their needs and desires; (2) peer communication, concerning the perceptions of adolescents that their peers are sensitive and responsive to their emotional states, as well as the depth and quality of involvement and verbal exchange; and (3) peer alienation, which refers to the feelings of isolation, anger, and detachment experienced by adolescents in their attachment relationships with peers11,13. These three dimensions reflect the various aspects of adolescents’ behavior and needs in peer relationships. Considering peer attachment as a single entity when exploring its association with Internet addiction may not allow for a deep understanding of the association between them. We can construct a network model of the three dimensions of peer attachment and Internet addiction through network analysis. At the same time, we explore the central factors and the bridge within this network model. To discern the unmet need underlying Internet addiction in adolescents is crucial. Identifying this need will enable the development of more precise and efficacious intervention strategies for mitigating their Internet addiction.

Network analysis utilizes observed variables as nodes, interconnected by edges that represent statistical relationships25. In this model, central factors are identified by nodes with the highest strength. A node with high strength indicates that its connections with other nodes are more significant, frequent, or influential than others26,27. The bridge is the essential node that links subnetworks of the overall network model. Its removal could substantially affect the connectivity of the overall network model28. The widespread use of network analysis in the psychological field has demonstrated its effectiveness in providing a visual representation of nodes associations and identifying central factors and the bridge29,30,31. Previous studies have indicated that intervening in the central factors and the bridge leads to more effective outcomes32,33.

Therefore, we aim to use network analysis to construct a network model between peer attachment and Internet addiction. This study focuses on two main issues: first, how peer attachment and Internet addiction are connected within a network model; and second, identifying the central factors and the bridge within this network model. The central factors and the bridge could inform the development of more targeted psychological intervention strategies aimed at addressing issues related to peer attachment and Internet addiction.

Methods

Participants

The participants of this study were recruited from a longitudinal cohort study based in Chongqing, China, which aimed to investigate the factors influencing pubertal development and its health implications in adolescents. A comprehensive description of this cohort has been provided in a previously published Cohort Profile34. The cohort selected four schools in Jiulongpo District with different geographic locations by purposeful sampling method in April 2014. This district has a typical urban-rural dual economic structure in the city zone of Chongqing. Consent forms were distributed to the parents of students in grades one to four in the selected primary schools. The parents of 1,237 students returned signed informed consent forms indicating their willingness to participate in the study. Participants can freely withdraw from the study at any point. Data for this study were collected from 782 students who completed a questionnaire during the 11th follow-up of the cohort in November 2019. The age range was 11 to 16 years old, including 369 boys and 413 girls. The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Review Committee of Chongqing Medical University, and all procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Measurement tools

Basic demographic characteristics

We collected basic demographic characteristics by the parent questionnaire, including the birthdays of children, and information regarding paternal and maternal education levels, parental relationship status, instances of divorce, family income per capita, and whether children are the only children. The parent questionnaire was to be taken home by the child for the parents to fill out and then brought back to school the next day to be collected. The scales for peer attachment and Internet addiction were completed by the child questionnaire. The trained researchers brought the child questionnaire to the schools for the students to complete in the classroom. To avoid the effects of unfamiliar environments on the psychological situation of adolescents, the researchers can guide the students if they cannot understand the questionnaire items.

Internet addiction

This survey used the Chinese version of the Young Internet Addiction Test (IAT) to measure the degree of Internet addiction of the study subjects35. The scale consists of 20 items rated on a Likert scale from 1(never) to 5(always). The scale scores range from 0 to 100. This version scale has demonstrated high reliability and validity in previous surveys conducted among children and adolescents36,37,38. Based on previous studies, an IAT total score of ≥ 50 was used as the cutoff value for the scale scores36,38. The Cronbach’s alpha value was 0.921 in this study.

Inventory of parent and peer attachment

The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA) developed by Armsden and Greenberg in 1987 was used to assess adolescents’ attachment to their parents and peers11. Based on our study objectives, we only used the peer attachment subscale from the IPPA scale. We aim to independently investigate the relationship between peer attachment and Internet addiction to gain a more nuanced understanding of the distinct role that peer attachment plays in adolescent Internet addiction. In this study, we measured peer attachment using the Chinese version of the IPPA scale. This version of the peer attachment scale has demonstrated high reliability and validity in previous surveys conducted among children and adolescents39,40. Adolescents respond to the items on a Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The highest possible score on the scale is 125 points. This section scale includes 25 items, which were divided into Peer Trust (5, 6, 8, 12, 13, 14, 15, 19, 20, 21), Peer Communication (1, 2, 3, 7, 16, 17, 24, 25) and Peer Alienation (4, 9, 10, 11, 18, 22, 23). Peer alienation is scored in reverse. The Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.891 in this study.

Statistical analysis

The survey data were collected using EpiData 3.1 to establish a database, which was subjected to double entry and logical error checking. We used the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to explore whether the IAT total score, as well as the scores for peer trust, peer communication, and peer alienation, followed a normal distribution. Wilcoxon test was used to compare between the scores on the scales of boys and girls. Spearman correlation was used to analyze the association between the three dimensions of peer attachment and Internet addiction. These statistical analyses were completed using SPSS 27.0.

R version 4.3.1 in R Studio was used for network analyses. We used the enhanced least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) approach and the extended Bayesian information criterion (EBIC) to build the network model. Then, we got a visualized network by the R packages “qgraph”41. All items of the IAT and dimensions of the IPPA were represented as nodes, and the relationship between these nodes was represented as an edge. The solid line indicated that the two nodes had a positive correlation, and the dotted line indicated that the two nodes had a negative correlation. The edge thickness means the strength of the association between nodes. The stronger the association between two nodes, the thicker the edge between them42. The three centrality indices, strength (the sum of the absolute values of all edges of a node), closeness (the inverse of the sum of largest indirect effects between nodes), and betweenness (the number of shortest paths between two other nodes that a node is part of) were used to describe the importance of nodes in the network43. The centrality indices were reported as a standardized value (z-scores) in this study. To identify the bridge between peer attachment and Internet addiction, we calculated the bridge expected influence through the “networktools” package to determine the key node that act as the bridge between communities. The accuracy and stability of the network model were assessed using the “bootnet” package44. We used the correlation stability coefficient (CS-coefficient) to describe the node centrality stability. According to the guidelines, the CS coefficient should not be below 0.25 and preferably above 0.5 42.

Results

Participant characteristics and the network nodes

A sample of 782 adolescents, aged 11 to 16 years (Mean age = 13.52, SD age = 1.17), participated in the survey, of whom 369 (47.2%) were boys. Detailed information regarding paternal and maternal education levels, parental relationship status, instances of divorce, family income per capita, and the only children is presented in Table 1. Descriptive statistics for the network nodes are shown in Table S1. The skewness ranged from − 0.61 to 1.52, and the kurtosis ranged from − 0.84 to 2.06.

The relationship between peer attachment and Internet addiction

The scores of peer trust, peer communication, peer alienation, and Internet addiction are presented in Table 2. No significant gender differences were observed in the scores for Internet addiction. Approximately 30.6% of the participants scored 50 or above on the Internet Addiction Test. The mean score of Internet addiction was 42.74 (SD = 13.31). Significant gender differences were observed in the dimensions of peer trust (Ζ = −4.36, p < 0.001) and peer communication (Ζ = −4.28, p < 0.001).

As shown in Table 3, Internet addiction was negatively correlated with the three dimensions of peer attachment: peer trust (r = −0.22, p < 0.01), peer communication (r = −0.17, p < 0.01), and peer alienation (r = −0.47, p < 0.01). Additionally, significant correlations among the three dimensions of peer attachment were observed. There was a significant positive correlation between peer trust and peer communication (r = 0.81, p < 0.01).

Network analysis

Estimated network

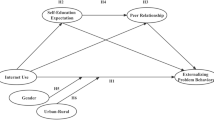

The network model of peer attachment and Internet addiction is presented in Fig. 1. It included 253 edges, 151 of which have non-zero weights (mean weight 0.03). Within the peer attachment network, the relationship between peer trust and peer communication is particularly strong. A significant positive correlation was found between PC (“peer communication”) and IA4 (“How often do you form new relationships with fellow online users?”). In Internet addiction network, there was a significant positive correlation between all the nodes. In the overall network model, the significant negative correlation was observed between PT (“peer trust”) and IA19 (“How often do you choose to spend more time online over going out with others?”), and PA (“peer alienation”) was significantly associated with nodes in Internet addiction. Overall, all three dimensions of peer attachment demonstrated significant associations with Internet addiction.

Network model estimation of loneliness, Internet addiction, and peer attachment among adolescents (N = 782). Notes: In the diagram, the orange nodes (IA1-IA20) indicate Internet addiction items, and the blue nodes (PA, PC, and PT) indicate dimensions of peer attachment. The purple line represents positive correlations. The red line represents negative correlations.

Centrality measure analysis

The strength centrality z-scores are presented in Fig. 2. The three nodes with the highest strength in the network model were PT (“peer trust”), IA2 (“How often do you neglect household chores to spend more time online?”), and IA12 (“How often do you fear that life without the Internet would be boring, empty, and joyless?”). IA19 (“How often do you choose to spend more time online over going out with others?”) had the highest betweenness. IA17 (“How often do you try to cut down the amount of time you spend online and fail?”) and IA19 (“How often do you choose to spend more time online over going out with others?”) demonstrated the highest closeness. Additionally, the standardized bridge excepted influence (1-step) for peer attachment and Internet addiction is shown in Fig. 3. Our analysis revealed that peer communication was the bridge between peer attachment and Internet addiction.

Network accuracy and stability

We evaluated the accuracy and stability of the network model. The bootstrapped confidence intervals for the edge weights are presented in Fig. S1, where the smaller gray area indicates higher accuracy. CS-coefficient was used to assess the stability of the centrality indices of this network. The stability of these centrality estimates is shown in Fig. S2, which reveals a high level of stability for strength (CS-coefficient = 0.75), closeness (CS-coefficient = 0.67), and betweenness (CS-coefficient = 0.28). The edge also had good stability (CS-coefficient = 0.75). Fig. S4 and S5 display the results of bootstrapped difference tests between edge weights and between node strength. Overall, this network had good accuracy and stability. Also, we had a good stability level of bridge stability (CS-coefficient = 0.75), as shown in Fig. S6.

Discussion

This study used the network analysis to explore the relationship between peer attachment and Internet addiction among Chinese adolescents. We found that peer trust, IA2 (“How often do you neglect household chores to spend more time online?”), and IA12 (“How often do you fear that life without the Internet would be boring, empty, and joyless?”) were the central factors in the network model of peer attachment and Internet addiction. In addition, peer communication acted as a bridge between peer attachment and Internet addiction in the network model.

The correlation analysis revealed a strong association between peer alienation and Internet addiction, which supports the Compensatory Internet Use Theory. This suggests that adolescents who feel more alienated from their peers are likely to turn to the Internet to fulfill their social needs. However, correlation analysis only indicates the relationship between two variables. Network analysis considers the association among all variables, revealing indirect relationships and the overall network model. Based on Attachment Theory, the three dimensions of peer attachment represent distinct attachment needs. We are interested in identifying which peer attachment needs could best prevent adolescent Internet addiction when fulfilled. Network analysis identified peer trust as a central factor within the network model. Peer trust refers to adolescents seeking understanding and respect for their needs and desires from their peers11. When adolescents perceive a lack of understanding or respect from their peers in real life, they may turn to compensatory social activities online23,45,46. Additionally, IA2 (“How often do you neglect household chores to spend more time online?”) and IA12 (“How often do you fear that life without the Internet would be boring, empty, and joyless?”) exhibited higher strength than other nodes in the network model. Ignoring responsibilities and experiencing significant emotional fluctuations are common symptoms observed in individuals with addiction47. Our findings are consistent with previous studies48,49. When adolescents are overly addicted to the Internet, ignoring their responsibilities, and experiencing mood swings when offline, it is a clear sign to intervene.

Simultaneously, our findings indicated that peer communication may serve as a bridge between peer attachment and Internet addiction. This indicates that peer communication plays a pivotal role in connecting the subnetworks of peer attachment and Internet addiction within the network model. Adolescents are more sensitive to the emotional feedback and judgment of their peers50. This feedback and support are precisely what adolescents obtain through high-quality communication with their peers in daily life. When adolescents’ need for emotional connection is unmet through real-life peer interactions, they often turn to increased online socialization as a compensatory measure. However, adolescents with Internet addiction are likely to prioritize online engagement over real-life peer interactions51. The absence of substantial real-life interactions prompts them to become more active on the Internet to compensate for the need to socialize. Prolonged socializing on the Internet may make it more difficult for them to interact with people in real life52,53.

Through network analysis, we identified the central factor and the bridge in the network model of peer attachment and Internet addiction. Peer trust plays the central factor in influencing other factors in the network model. This suggests an association between higher levels of trust in peers and more frequent reports of deeper and more meaningful communication among adolescents. Similarly, there appears to be a correlation between perceptions of peer unreliability and self-reported feelings of alienation. However, it is important to note that these findings do not establish a causal relationship because the study was a cross-sectional design. Our findings are consistent with Attachment Theory, which posits that trust is fundamental to peer relationships11,54. Moreover, our analysis indicated that peer communication serves as a bridge between peer attachment and Internet addiction. Both correlation and network analyses indicated a significant association between peer communication and peer trust, suggesting that peer trust may impact Internet addiction in adolescents through its influence on communication. When adolescents lose trust in their peers, they are likely to decrease their communication with them, subsequently increasing their reliance on compensatory online socialization45. This result also consistent with the Compensatory Internet Use Theory16. Based on our study findings, establishing trust among peers is crucial. It promotes communication between adolescents and their peers in real life, instead of relying on compensatory social interactions through the Internet55,56. While the Internet offers adolescents a convenient platform for socializing, excessive reliance on online interactions can negatively impact their social skills and emotional development. Compared to real-life social interactions, online interactions lack non-verbal cues, such as body language and facial expressions, which play a significant role in conveying emotions and intentions57. Studies suggest that the absence of these cues in online interactions can impair interpersonal perception, potentially increasing the risk of misunderstandings and conflicts58,59. Furthermore, online interactions often consist of simple information exchange and lack the emotional depth and complexity of real-life social interactions58,60. Prolonged dependence on online interactions may lead to superficial emotional connections, which can adversely affect the mental health61,62and social adaptation of adolescents63 in adolescents. Therefore, it is important for adolescents to promote real-life communication.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged in this study: (1) This study was a network analysis based on cross-sectional survey data and was unable to explore the causal relationship between peer attachment and Internet addiction; (2) The sample population was drawn from a specific geographic area and was not evenly distributed across age and grade levels, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings; (3) All measurements were by self-report and may be subject to bias; (4) Additionally, this study did not consider potential confounding variables stemming from parental attachment, which could also play a significant role in influencing the relationship between peer attachment and Internet addiction. This oversight may limit the comprehensive understanding of the factors contributing to Internet addiction among individuals. Future studies could further observe the relationship between peer attachment and Internet addiction through a longitudinal research design and consider incorporating measures of parental attachment to address these limitations.

Conclusions

This study used network analysis to explore the associations between the three dimensions of peer attachment and Internet addiction among adolescents. We found that peer trust was the central factor in the network model. By enhancing adolescents’ trust in their peers and promoting communication and interaction in real life, we can effectively alleviate their Internet addiction. Our findings provide evidence for the feasibility of intervening in adolescent Internet addiction from the perspective of peer relationships. We hope that our study can assist in formulating strategies to prevent adolescent Internet addiction, such as enhancing parental supervision and promoting positive online activities.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Shaw, M. & Black, D. W. Internet addiction: definition, assessment, epidemiology and clinical management. CNS Drugs. 22, 353–365 (2008).

Lozano-Blasco, R., Robres, A. Q. & Sánchez, A. S. Internet addiction in young adults: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 130, 107201 (2022).

Ding, H., Cao, B. & Sun, Q. The association between problematic internet use and social anxiety within adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1275723 (2023).

Tang, J. et al. Association of internet addiction with nonsuicidal Self-injury among adolescents in China. JAMA Netw. Open. 3, e206863 (2020).

Zhou, N. & Fang, X. Beyond peer contagion: unique and interactive effects of multiple peer influences on internet addiction among Chinese adolescents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 50, 231–238 (2015).

Badenes-Ribera, L., Fabris, M. A., Gastaldi, F. G. M., Prino, L. E. & Longobardi, C. Parent and peer attachment as predictors of Facebook addiction symptoms in different developmental stages (early adolescents and adolescents). Addict. Behav. 95, 226–232 (2019).

Teng, Z., Griffiths, M. D., Nie, Q., Xiang, G. & Guo, C. Parent-adolescent attachment and peer attachment associated with internet gaming disorder: A longitudinal study of first-year undergraduate students. J. Behav. Addictions. 9, 116–128 (2020).

Delgado, E., Serna, C., Martínez, I. & Cruise, E. Parental attachment and peer relationships in adolescence: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19 (2022).

Giddens, A. & Bowlby, J. Attachment and loss, I: attachment. Br. J. Sociol. 21, 111 (1970).

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E. & Wall, S. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation. (1979).

Armsden, G. C. & Greenberg, M. T. The inventory of parent and peer attachment: individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 16, 427–454 (1987).

Schoeps, K., Mónaco, E., Cotolí, A. & Montoya-Castilla, I. The impact of peer attachment on prosocial behavior, emotional difficulties and conduct problems in adolescence: the mediating role of empathy. PloS One. 15, e0227627 (2020).

Gorrese, A., Ruggieri, R. & Peer Attachment A Meta-analytic review of gender and age differences and associations with parent attachment. J. Youth Adolesc. 41, 650–672 (2012).

Monacis, L., de Palo, V., Griffiths, M. D. & Sinatra, M. Exploring individual differences in online addictions: the role of identity and attachment. Int. J. Mental Health Addict. 15, 853–868 (2017).

Assunção, R. S., Costa, P. & Tagliabue, S. Mena Matos, P. Problematic Facebook use in adolescents: associations with parental attachment and alienation to peers. J. Child Fam. Stud. 26, 2990–2998 (2017).

McKenna, K. Y. A., Green, A. S. & Gleason, M. E. J. Relationship formation on the internet: what’s the big attraction?? J. Soc. Issues. 58, 9–31 (2002).

Kardefelt-Winther, D. A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: towards a model of compensatory internet use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 31, 351–354 (2014).

Elhai, J. D., Levine, J. C. & Hall, B. J. The relationship between anxiety symptom severity and problematic smartphone use: A review of the literature and conceptual frameworks. J. Anxiety Disord. 62, 45–52 (2019).

D’Arienzo, M. C., Boursier, V. & Griffiths, M. D. Addiction to social media and attachment styles: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Mental Health Addict. 17, 1094–1118 (2019).

Ballarotto, G., Volpi, B., Marzilli, E. & Tambelli, R. Adolescent Internet Abuse: A Study on the Role of Attachment to Parents and Peers in a Large Community Sample. BioMed research international 5769250 (2018). (2018).

Reiner, I. et al. Peer attachment, specific patterns of internet use and problematic internet use in male and female adolescents. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 26, 1257–1268 (2017).

Yang, X., Zhu, L., Chen, Q., Song, P. & Wang, Z. Parent marital conflict and internet addiction among Chinese college students: the mediating role of father-child, mother-child, and peer attachment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 59, 221–229 (2016).

Feeney, B. C., Cassidy, J. & Ramos-Marcuse, F. The generalization of attachment representations to new social situations: predicting behavior during initial interactions with strangers. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 95, 1481–1498 (2008).

Vagos, P. & Carvalhais, L. The impact of adolescents’ attachment to peers and parents on aggressive and prosocial behavior: A Short-Term longitudinal study. Front. Psychol. 11, 592144 (2020).

Faust, K. & Wasserman, S. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications (Cambridge University Press, 1994).

Borsboom, D. A network theory of mental disorders. World Psychiatry: Official J. World Psychiatric Association (WPA). 16, 5–13 (2017).

Braun, U. et al. From maps to Multi-dimensional network mechanisms of mental disorders. Neuron 97, 14–31 (2018).

McNally, R. J. Can network analysis transform psychopathology? Behav. Res. Ther. 86, 95–104 (2016).

Borsboom, D. & Cramer, A. O. Network analysis: an integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Ann. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 9, 91–121 (2013).

Cao, X. et al. Sex differences in global and local connectivity of adolescent posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 60, 216–224 (2019).

Vanzhula, I. A., Calebs, B., Fewell, L. & Levinson, C. A. Illness pathways between eating disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms: Understanding comorbidity with network analysis. Eur. Eat. Disorders Review: J. Eat. Disorders Association. 27, 147–160 (2019).

Castro, D. et al. The differential role of central and Bridge symptoms in deactivating psychopathological networks. Front. Psychol. 10, 2448 (2019).

Groen, R. N. et al. Comorbidity between depression and anxiety: assessing the role of Bridge mental States in dynamic psychological networks. BMC Med. 18, 308 (2020).

Wu, D. et al., Cohort Profile: Chongqing Pubertal Timing and Environment Study in China with 15 Follow-Ups since 2014. in Future, Vol. 2 107–125 (2024).

Chin, F. & Leung, C. H. The concurrent validity of the internet addiction test (IAT) and the mobile phone dependence questionnaire (MPDQ). PloS One. 13, e0197562 (2018).

Cai, H. et al. Internet addiction and residual depressive symptoms among clinically stable adolescents with major psychiatric disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic: a network analysis perspective. Translational Psychiatry. 13, 186 (2023).

Lai, C. M. et al. Psychometric properties of the internet addiction test in Chinese adolescents. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 38, 794–807 (2013).

Li, C. et al., The mediation and interaction effects of Internet addiction in the association between family functioning and depressive symptoms among adolescents: A four-way decomposition. J. Affect. Disord. (2024).

Lin, S. et al. Cybervictimization and non-suicidal self-injury among Chinese adolescents: A longitudinal moderated mediation model. J. Affect. Disord. 329, 470–476 (2023).

Yu, T., Hu, J., Zhang, W., Zhang, L. & Zhao, J. Influence of childhood psychological maltreatment on peer attachment among Chinese adolescents: the mediation effects of emotion regulation strategies. J. Interpers. Violence. 38, 11935–11953 (2023).

Epskamp, S. & Fried, E. I. A tutorial on regularized partial correlation networks. Psychol. Methods. 23, 617–634 (2018).

Epskamp, S., Borsboom, D. & Fried, E. I. Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behav. Res. Methods. 50, 195–212 (2018).

Jongerling, J., Epskamp, S. & Williams, D. R. Bayesian uncertainty Estimation for Gaussian graphical models and centrality indices. Multivar. Behav. Res. 58, 311–339 (2023).

Bringmann, L. F. et al. Psychopathological networks: theory, methods and practice. Behav. Res. Ther. 149, 104011 (2022).

Sela, Y., Zach, M., Amichay-Hamburger, Y., Mishali, M. & Omer, H. Family environment and problematic internet use among adolescents: the mediating roles of depression and fear of missing out. Comput. Hum. Behav. 106, 106226 (2020).

Weimer, B. L., Kerns, K. A. & Oldenburg, C. M. Adolescents’ interactions with a best friend: associations with attachment style. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 88, 102–120 (2004).

Brand, M. et al. The interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model for addictive behaviors: update, generalization to addictive behaviors beyond internet-use disorders, and specification of the process character of addictive behaviors. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 104, 1–10 (2019).

Cai, H. et al. Identification of central symptoms in internet addictions and depression among adolescents in Macau: A network analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 302, 415–423 (2022).

Zhao, Y., Qu, D., Chen, S. & Chi, X. Network analysis of internet addiction and depression among Chinese college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 138, 107424 (2023).

Gunther Moor, B., van Leijenhorst, L., Rombouts, S. A. R. B., Crone, E. A. & Van der Molen, M. W. Do you like me? Neural correlates of social evaluation and developmental trajectories. Soc. Neurosci. 5, 461–482 (2010).

Xiao, Z. & Huang, J. The relation between college students’ social anxiety and mobile phone addiction: the mediating role of regulatory emotional Self-Efficacy and subjective Well-Being. Front. Psychol. 13, 861527 (2022).

Firth, J. et al. Can smartphone mental health interventions reduce symptoms of anxiety? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Affect. Disord. 218, 15–22 (2017).

Kwak, M. J., Cho, H. & Kim, D. J. The role of motivation systems, anxiety, and low Self-Control in smartphone addiction among smartphone-Based social networking service (SNS) users. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19 (2022).

Roelofs, J., Onckels, L. & Muris, P. Attachment quality and psychopathological symptoms in clinically referred adolescents: the mediating role of early maladaptive schema. J. Child. Fam Stud. 22, 377–385 (2013).

Durkee, T. et al. Prevalence of pathological internet use among adolescents in Europe: demographic and social factors. Addict. (Abingdon England). 107, 2210–2222 (2012).

Kaess, M. et al. Pathological internet use among European adolescents: psychopathology and self-destructive behaviours. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 23, 1093–1102 (2014).

Andersen, S. M., Reznik, I. & Manzella, L. M. Eliciting facial affect, motivation, and expectancies in transference: significant-other representations in social relations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 71, 1108–1129 (1996).

Lieberman, A. & Schroeder, J. Two social lives: how differences between online and offline interaction influence social outcomes. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 31, 16–21 (2020).

Achterhof, R. et al. Adolescents’ real-time social and affective experiences of online and face-to-face interactions. Comput. Hum. Behav. 129, 107159 (2022).

Best, P., Manktelow, R. & Taylor, B. Online communication, social media and adolescent wellbeing: A systematic narrative review. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 41, 27–36 (2014).

Harness, J., Domoff, S. E. & Rollings, H. Social media use and youth mental health: Intervention-Focused future directions. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 25, 865–871 (2023).

Steinsbekk, S., Nesi, J. & Wichstrøm, L. Social media behaviors and symptoms of anxiety and depression. A four-wave cohort study from age 10–16 years. Comput. Hum. Behav. 147 (2023).

Firth, J. et al. From online brains to online lives: Understanding the individualized impacts of internet use across psychological, cognitive and social dimensions. World Psychiatry: Official J. World Psychiatric Association (WPA). 23, 176–190 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the children and parents who participated in this study. Without their valuable time, cooperation, and willingness to share their experiences, this research would not have been possible. We also extend our appreciation to the research team and field surveyors for their dedication and professionalism in data collection.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science Fund Project (No. 81973067), Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing, China (No. CSTB2023NSCQ-MSX0133), and Program for Youth Innovation in Future Medicine, Chongqing Medical University (No. W0054).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: X.F.; Methodology: X.F., W.W.,J.Z.; Data curation: W.W.,J.Z.; Writing—Original Draff: X.F.,J.L.; Writing—Review and Editing: C.P. and Q.L.All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Feng, X., Wang, W., Luo, J. et al. Network analysis of peer attachment and internet addiction among chinese adolescents. Sci Rep 15, 10711 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95526-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95526-5