Abstract

Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicon L.) is amongst the most important fresh vegetables used worldwide. Growth and yield of tomatoes are constrained by a lack of improved varieties and inefficient agronomic methods, such as staking. Recognizing the fundamental importance of staking to reduce the effect of high moisture and disease on the growth and yield of tomatoes is essential. A field study was conducted on the effects of staking techniques on the growth and yield of tomato varieties in northwestern Ethiopia at the Department of Horticulture, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Debre Markos University, demonstration site under irrigation conditions in two growing seasons, 2021/22 and 2022/23. Cochero, Eshet, Metadel, and Miya varieties were used while three staking techniques (single-string staking as treatment one (S1), Florida weave string staking as treatment two (S2), and non-staking as a control treatment (S0)) were used. A randomized complete block design with three replications was used. Data were collected and analyzed using SAS 9.2 software. Means were separated by using LSD at a 5% probability level. Based on the results of the present experiment, Metadel with single-string staking recorded the maximum fruit yield (96.25 t ha− 1) and (103.72 t ha− 1) in both seasons. On the other hand, the Metadel variety combined with single-string staking gave the maximum marketable yield of 91.09 t ha− 1 and 96.97 t ha− 1 in the first and second seasons, respectively. Therefore, the adoption of Metadel with single-string staking techniques enables farmers to enhance productivity, reduce costs, and promote sustainable agricultural systems in regions of similar agro-ecological zones.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicon L.) is one of the most significant edible and nutritious vegetable crops and is widely grown in tropical, subtropical, and temperate climates worldwide1.It belongs to the family Solanaceae (also known as the nightshade family), genus Lycopersicon, subfamily Solanoideae, and tribe Solaneae2.It originally came from the tropical areas of Mexico, and then from Peru. It is an important nutritious and delicious vegetable crop that originated in Mexico and spread throughout the world following the Spanish colonization of the Americas3.

In Ethiopia, a number of tomato varieties have been recommended and released for production. These include Marglobe, Melka Shola, Melka salsa, Roma VF, Napoli VF, Money Maker, Cochero, Eshet, Metadel, and Miya. The varietal characteristics and sources of tomato varieties are important for understanding their agricultural potential and suitability for different growing conditions. Metadel tomatoes are known for their high yield and disease resistance. They typically have a good balance of sweetness and acidity, making them versatile for various culinary uses. This variety is primarily cultivated in Ethiopia, where it has been developed to thrive in local agro-ecological conditions. On the other hand, Eshet are characterized by their firm texture and vibrant color. They are often praised for their excellent flavor and are suitable for both fresh consumption and cooking. Like Metadel, Eshet tomatoes are also sourced from Ethiopia, specifically bred for the region’s climatic conditions. Cochero are recognized for their robust growth and high productivity. They have a slightly elongated shape and are favored for their rich taste, making them ideal for sauces and pastes. This variety is cultivated in various regions, including Ethiopia, where it has been adapted to local agricultural practices. Miya tomatoes are known for their early maturity and high yield potential. They are typically round and have a juicy texture, making them popular for salads and fresh dishes. Miya tomatoes are also sourced from Ethiopia, developed to meet the demands of local farmers and consumers. These varieties are primarily sourced from Ethiopian agricultural research programs and institutions that focus on developing crops suited to local growing conditions. Farmers can typically obtain seeds from local agricultural extension services, seed companies, or cooperatives that distribute improved varieties.

Following potatoes and sweet potatoes, tomatoes are the third most produced vegetable crop and the most processed vegetable worldwide4. According to data from the Food and Agriculture Organization Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT), the world produced 186.821 million metric tons of tomatoes on 5,051,983 ha in 2020, with an average yield of 37.1 t ha− 1.Asia led overall in regional production (44.7%), followed by Europe (23.3%), and the Americas (20.3%)5. Although no definite time has been recorded regarding the introduction of tomatoes to Ethiopia, the crop is currently cultivated during the rainy and dry seasons by smallholder, commercial, and private farms. According to Central Statistical Agency (CSA) data, from 2019/20 to 2020/21 meher season production of two years, small-scale farmers, the area of production of tomatoes in Ethiopia increased from 5978.22 hectares to 6433.73 hectares which was a 7.62% change in the area of production6. From these areas, there was a 21.94% change in production from 344,008.98 quintals to 419,482.70 quintals. This indicates the productivity was increased from 57.54 t ha− 1 to 65.20 t ha− 1 which was 13.31% change in production. The average annual tomato production in Ethiopia is often low (12.5 tha− 1) compared to that in neighboring African countries such as Kenya (16.4 tha− 1)7. Although there are many reasons for this low level of production and productivity of tomatoes in Ethiopia, the lack of selection of desirable varieties for the given agro-ecology and lack of appropriate and cost-effective staking materials are the main problems affecting the yield and yield components of tomatoes.

The comparison of crop yields under different staking techniques to those reported in regions with similar climates is a complex issue influenced by various factors, including climate variability, irrigation practices, and agricultural management techniques. Many diseases and pests originate from the soil. By staking tomatoes, the lower leaves and stems are kept off the ground, which helps prevent soil born disease from infecting the plants. In Ethiopian context; particularly in regions with similar agroecological conditions, effective tomato staking techniques are crucial for enhancing yield and managing the growth of tomato plants. In nature, the stem of the tomato plant is flabby and cannot carry branches, including fruits. There is inevitably mutual shade between branches and leaves as plants grow, which results in a lack of light in the lower canopy. Thus, fruit yield losses are caused by soil. Plants that receive insufficient light undergo morphological and physiological changes, such as an increase in the area of a particular leaf and in height, which maximizes the amount of light captured to meet the requirements of photosynthesis, but produces more pronounced shade8. Because of the overlapping of leaves, the photosynthetic processes were hampered9. Furthermore, through intense agricultural cultivation, competition for light inside the canopy can cause premature leaf senescence, which impairs the capacity of plants to reproduce, resulting in subsequent yield losses, thus affecting the quality of the produce10.

The relevance of staking techniques and specific crop varieties are often developed to thrive in the specific climatic and soil conditions of the region, ensuring better growth and higher yields. Moreover, Varieties that are resistant to local pests and diseases can significantly reduce crop losses, making them particularly valuable for farmers in the area. By improving productivity and reducing input costs, these techniques can enhance the economic viability of farming in the region, contributing to overall rural development. Therefore, the study is imperative to investigate the effect of staking techniques on growth and yield of tomato varieties.

Materials and methods

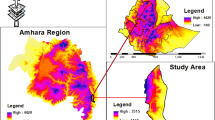

Description of the experimental site

The experiment was carried out in 2021 and 2022 under irrigation conditions throughout the two growing seasons at the Debre Markos University, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Horticulture Department demonstration site. The geographical location of Debre Markos is 10°20’ N, 37°43’ E. with an altitude of 2,446 m above sea level (m.a.s.l.). It is situated 265 km southeast of Bahir Dar, the capital of the Amhara National Regional State, and 300 km northwest of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The average annual rainfall was 1380 mm, with the lowest and highest temperatures of 15 °C and 25 °C, respectively.

Experimental materials

Four tomato varieties (Cochero, Eshet, Metadel, and Miya) obtained from the Fogera National Rice Research & Training Centre (FNRRTC) and three staking (Single-string staking, Florida weave string staking and non-staking) techniques were used in the experiment, as indicated in Table 1. The selection of tomato varieties for an experiment was based on their availability and adaptability to the specific experimental conditions, such as soil type, climate, irrigation methods, and disease management practices. The applicability of the findings to other areas may be affected by differences in environmental conditions, genetic diversity, and the specific traits of other tomato cultivars grown.

Tomato varieties

Tomato varieties refer to the different types of tomatoes that have been cultivated for specific characteristics such as flavor, size, shape, color, and growth habits11. Each variety is developed to meet various agricultural needs and culinary preferences, making tomatoes one of the most versatile fruits in cooking. These varieties are primarily sourced from Ethiopian agricultural research programs and institutions that focus on developing crops suited to local growing conditions. Farmers can typically obtain seeds from local agricultural extension services, seed companies, or cooperatives that distribute improved varieties.

Cochero

Cochero tomatoes are medium-sized, round, and have a deep red color with a slightly sweet flavor. They are versatile for both fresh consumption and cooking. This variety has a determinate growth pattern, allowing for good production in limited spaces while still benefiting from staking. Cochero is known for its resilience against various diseases, making it a reliable choice for farmers.

Eshet

Eshet tomatoes are typically larger, round, and glossy red. They are recognized for their excellent flavor and high juice content, making them ideal for sauces and pastes. This variety grows tall and requires strong staking or support to manage its sprawling branches. Proper pruning is beneficial to maximize airflow and fruit development. Eshet exhibits good resistance to common tomato diseases, contributing to consistent yields.

Metadel

Metadel tomatoes are medium to large, round, and smooth with a vibrant red color. They are known for their balanced flavor, making them versatile for both fresh consumption and cooking. This variety has a compact growth habit, making it ideal for small spaces or container gardening. It performs well under staking methods that support upright growth. Metadel is often resistant to common tomato diseases, which helps improve yield and quality in various growing conditions.

Miya

Miya tomatoes are medium-sized, oblong, and rich red. They are praised for their sweet flavor and juicy texture, making them perfect for salads and fresh dishes. This variety has a vigorous growth habit, requiring adequate support through staking or trellising. It can produce a high yield throughout the growing season. Miya is known for its resistance to certain diseases, enhancing its viability in diverse climates.

Staking techniques

Staking is a critical practice in tomato cultivation that significantly contributes to disease prevention. By promoting airflow, reducing soil contact, and facilitating maintenance, staking helps create a healthier growing environment for tomato plants, ultimately leading to better yields and fruit quality. In addition, staking plays a vital role in disease prevention for tomato plants and other crops. It allows for better air circulation, which helps lower humidity levels around the foliage. This is crucial in preventing fungal diseases, such as blight, which thrive in moist environments. Staking techniques for tomato varieties offer innovative solutions to modern agricultural challenges by elevating plants off the ground, enhances air circulation, reducing the risk of fungal diseases and promoting healthier plants. These techniques are not only practical but also crucial in adapting to changing environmental conditions and food production demands. Single-string staking, Florida weave string staking, and non-staking techniques were employed in the experiment and impacted tomato plant growth and yield in different ways. Choosing the appropriate staking technique depends on factors such as tomato variety, available space, labor resources, and desired yield and fruit quality12.

Single-string staking

In single-string staking, each tomato plant is supported by a single vertical string tied to a sturdy overhead support, and provides good support to the main stem of the tomato plant, allowing it to grow upright. This promotes better air circulation around the plant, and improves fruit quality by reducing contact with soil and preventing fruit rot, results in higher yields per plant compared to non-staking methods.

Florida weaves string staking

Florida weaves string staking involves creating a horizontal support system using stakes placed at regular intervals in the row, and tomatoes are woven between twine strings that run horizontally, creating a mesh-like structure. This provides strong support for tomato plants as they grow horizontally along the row and maximizes space efficiency by allowing plants to be grown closely together in rows, which can increase overall yield per unit area. However, the Florida weave string staking technique is more labor-intensive than single-string staking as it requires continuous adjustment of the strings and supports as plants grow.

Non-staking

Non-staking technique involves allowing tomato plants to grow without additional vertical support structures. It requires more space per plant compared to staked methods and increased risk of disease due to reduced air circulation around the plants results in lower yields per plant compared to staked methods, especially in cases where plants are not adequately managed or supported.

Treatments, design and field layout

A randomized complete block design (RCBD) with three replications was used in a factorial arrangement. Four tomato varieties (Cochero, Eshet, Metadel, and Miya) were randomly combined using three staking techniques (single-string staking, Florida weave string staking, and non-staking. A total of 12 treatments were replicated three times with 36 observation plots. The treatments were randomly assigned to the experimental plots, and the gross area of the experiment was 428.75 m2. Each experimental plot was 2.4 m long and 3.5 m wide (with a total plot size of 8.4 m2) with a spacing of 0.5 m between plots and 1 m between blocks. Plants and rows were spaced 30 cm and 70 cm apart, respectively. Each plot had five rows containing eight plants per row, with a total of 40 plants per plot. The Harvester (net plot) area was 2.4 m long with 2.1 m width (three middle rows) equals 5.04m2.

Data collection

Data were collected on a plant-plot basis. The parameters chosen for measuring the effectiveness of staking techniques in tomato cultivation are vital for understanding their impact on plant growth, yield, disease resistance, labor efficiency, and environmental sustainability. By clarifying the relevance of these parameters within the context of the study, researchers can provide actionable insights for growers, ultimately leading to improved practices and outcomes in tomato production. This comprehensive justification ensures that the study is grounded in practical agricultural needs and scientific principles. Plant data were collected on plant height, number of primary branches, number of flowers per cluster, number of fruits per plant, number of marketable fruits per plant, number of unmarketable fruits per plant, and total fruit yield from three sample plants per row, which were taken randomly with a total of nine plants per plot from the three middle rows, leaving a row from each side of the plot as borders to reduce border effects. On the other hand, plot data were collected from the three net harvestable rows of each plot on days to 50% flowering and days to 50% fruit maturity.

Economic analysis

Partial budgeting is a method of organizing experimental data and information about the costs and benefits of various alternative treatments (CIMMYT, 1988). The economic analysis was carried out by using the methodology described in CIMMYT (1988) in which prevailing market prices for inputs at sowing and for outputs at harvesting was used. All costs and benefits were calculated on hectare basis in Ethiopian Birr (ETB). For this analysis, economic costs and benefits associated with methods of staking on different tomato varieties were evaluated. String cost was an important cost to tie the tomato branches with the staked wood, whereas, staking materials were involved in supporting the branches in to upright position. Labour cost was also involved for doing the overall agronomic practice including staking. After the overall calculations of the total variable costs for the operation of this experiment, there would be gross benefits. Then the net benefits were calculated by subtracting the total variable cost from the gross benefit. Finally, it was possible to compare the money we get from the sales of tomatoes on each treatment combinations, and the differences were taken to show the feasibility of using staking in tomato production.

Data analysis

Before performing an analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., 2008), the data were first validated to meet all ANOVA assumptions. The assumptions are crucial because violations can lead to inaccurate conclusions from the ANOVA analysis. The data measurements within each group were independent of each other, and the sampling distribution of the mean was normal, which is important for making valid inferences about population means. Moreover, the assumption, known as homoscedasticity, ensures that the variability within each group is consistent and that comparisons between groups are reliable. The analysis employed the ANOVA model Xij = µ + bi+sj+vk+sv(jk) + εijk.

Where Xij is any observation for which i is the treatment factor, j is the blocking factor, and ANOVA is analysis of variance. Grand mean (µ), block effect (bi), staking effect (sj), variety effect (vk), interaction effect (sv(jk)), and random error (εijk) are the variables. The least significant difference (LSD) test was used to separate means when ANOVA revealed significant differences at a 5% significance level14.

Results and discussion

Debre Markos has a temperate and warm climate, typical of the elevated portions of Ethiopia. Despite its proximity to the equator, the climate is classified as a subtropical highland, despite its proximity to the equator. The average minimum and maximum temperatures were 15°C and 25°C, respectively, and the average annual rainfall was 1380 mm. The Temperature and rainfall distribution data for Debre Marko during the experimental period are listed in (Table 2).

Effect of staking techniques on phonological and growth parameters of tomato varieties

Plant height

Plant height is a key factor in determining plant growth during the growing season. According to Table 3, the results of the analysis of variance showed that in both seasons, the interaction between variety and staking techniques was highly significant (p < 0.01). According to the data, the Eshet variety with single-string staking had the tallest plants, measuring (112.44 cm) and (106.21 cm), in the two growing seasons, respectively. Conversely, the treatment combination of Cochero with non-staking techniques resulted in the shortest plant heights, measuring (52.73 cm) and (49.75 cm) in both seasons.

Since the plants were straight and supported by staking, nearly every vine on the plant was equally exposed to sunlight for better photoassimilative partitioning, which may have contributed to the largest plant height seen from Eshet with single-string staking. However, in terms of non-staking, the plants were left unsupported by any material; therefore, the leaves were compacted at the center and did not allow the free penetration of light and air circulation. However, inherent genetic differences among varieties can be considered16.

Number of primary branches per plant

The interaction effect between staking methods and variety concerning the number of primary branches in both seasons was not significant (p > 0.05), as indicated in (Table 4). Moreover, the main effect of the staking methods in both growing seasons was not significant, and they were statistically similar. There were no significant differences in the number of primary branches between the two growing seasons. However, the main effect of variety in each season was highly significant (P < 0.01). The maximum number of primary branches per plant was recorded for the Miya variety (8.44) in the first season and (8.54) in the second season. The lowest number of primary branches per plant was recorded for the Eshet variety (4.88) and (4.79) in the first and second season, respectively. Probably the staking methods might have influenced the plant height as the plants were raised and supported by stakes, which allowed the leaves to get access to light for photosynthesis, in turn favoring the number of branches and trusses, whereby producing more flowers and fruits.

The present results are in agreement with17, the difference in the number of primary branches could be due to genetic factors. However, according to these authors, the number of primary branches was influenced by the staking methods; as the plants grew and received more energy from sunlight, a greater number of primary branches developed.

Days to 50% flowering

According to18, days to 50% flowering is one of the important phonological parameters and determinant factors for the growth and productivity of tomato plants. The results of this study indicated that the interaction effect between tomato varieties and staking techniques did not show any significant difference in either season (p > 0.05) on days to 50% flowering, as indicated in Table 5. However, in terms of staking techniques, the non-staking treatment plots (55.33) and (54.94) had the maximum days to 50% flowering in both seasons. In contrast, single-string staking required a minimum number of days to attain 50% flowering (52.41) and (48.37). The maximum number of days to 50% flowering was recorded for the Eshet variety (56.67) and (54.73) in the first and second seasons, respectively. On the other hand, Metadel (52.33) and (50.33) took the minimum days to attain 50% flowering.

The current findings coincide with those of19 investigators discovered that variations in the genetic composition of the cultivars were the cause of the variation in 50% flowering production. Days to 50% flowering ranged from 52.33 to 56.67, which is incompatible with the findings of20 who found that days to 50% flowering of tomato varieties ranged between 38 and 49, perhaps their working sites were much warmer than that of the experimental site in the present study.

Days to 50% fruit maturity

Although there were no significant (p > 0.05) interaction effects observed in both seasons, the results of the main effect indicated that both staking techniques and varieties were highly significant (p < 0.001) in affecting the number of days to attain 50% fruit maturity, either by enhancing or delaying the time required, as indicated in (Table 6). Concerning the staking techniques, the maximum days to fruit maturity were recorded for the non-staking (123.91) and non-staking (119.32) fruits in both seasons. In contrast, the lowest days to fruit maturity were recorded for single-string staking (112.41) and (109.92) in the two-season trial. Regarding varieties, Eshet (129.89) and (125.31) had the maximum number of days to fruit maturity in both the seasons. However, the minimum number of days required for fruit maturity was recorded for the Metadel variety (108.11) and (101.82) in the first and second season, respectively.

Varietal differences in days to 50% fruit maturity were highly significant (p < 0.01) but not due to seasonal variations. Among the varieties, Metadel was the earliest to mature, whereas Eshet had the maximum number of days to reach 50% maturity. Varietal differences may be due to the inherent genetic variability of crops. The early or late stage of fruit maturity is attributed to its genotypic characteristics. Moreover21, reported that a delay in flowering could lead to delayed fruit maturity in tomatoes. According to22 the earliness or lateness of fruit maturity is attributed to its genotypic characteristics.

Number of flowers per cluster

There was no interaction effect between staking technique and cultivar on the overall number of flowers per cluster, according to the analysis of variance, at p > 0.05. As shown in Table 7, there was a highly significant difference between the primary effects of varieties and staking techniques at (p < 0.01) and (p < 0.05), respectively, even though seasonal variations were not significant. Regarding staking techniques, the highest number of flowers per cluster was found for single-string stacking in both seasons (6.87 and 6.89). The lowest number of non-staking flowers per cluster in the two years was (6.45 and 5.67). In terms of variety, Miya had the highest number of blooms per cluster in the first and second seasons at (7.87) and (8.00). Nonetheless, in both seasons, Eshet (5.69) and Eshet (5.87) produced the lowest numbers of flowers per cluster23. found that genotypic variation in the number of flowers per cluster was considerable, which is consistent with the results of this study. Genetic differences across tomato genotypes may have contributed to the diversity in the number of blossom clusters per plant23.

Impact of staking techniques on yield and yield related traits of tomato varieties

Number of fruits per plant

As shown in (Table 8), the interaction effect between variety and staking technique revealed a highly significant (p < 0.01) variation in the number of fruits per plant. Furthermore, a significant variance in the quantity of fruits per plant was noted owing to the seasonal variation. With single-string staking, Miya produced the greatest number of fruits per plant in the two seasons (63.86) and (69.02), and these results were statistically similar. In contrast, the Cochero variety using non-staking techniques reported the lowest fruits (22.94) and (23.87). Some plant types were grown and supported by stakes, which might allow the leaves to access light for photosynthesis, favoring the number of branches, overall height, and trusses by producing more flowers and fruits24.

Number of marketable fruits per plant

Table 9 shows significant (p < 0.01) interaction between staking techniques and variety in the number of marketable fruits per plant. With single-string staking, the Miya variety produced the most marketable fruits in the first and second seasons, respectively, with (54.01) and (58.31). Conversely, the Eshet (13.92) and (13.97) cultivars with non-staking had the lowest number of marketable fruits per plant. Because single-string staking produces more marketable fruits, it allows branches and leaves to be exposed for aeration and efficient light receipt. Staking crops is advised by25 for a larger yield of quality fruits. Staking increases the production of high-quality fruits, lowers the percentage of unmarketable fruits, and increases fruit yield26. tomato plants staking is suggested to increase fruit yield and decrease the percentage of fruit that is culled.

Number of unmarketable fruits per plant

The number of unmarketable fruits per plant varied significantly (p < 0.01), depending on the interaction between the varieties and staking techniques, as shown in Table 10. With non-staking (32.28) and non-staking (30.75) fruits in both seasons, the Miya variety produced the greatest number of unmarketable fruits. In contrast, the Metadel cultivar with single-string staking had the lowest unmarketable fruits per plant (3.59) and (3.41) in both the seasons. These findings are aligned with those of those who observed more unmarketable fruits from non-staked plots caused by the rotting of fruits from moist soil. Unmarketable fruits recorded by staking methods are mostly damaged by birds and physiological disorders27.

Marketable fruit yield per hectare

Figure 1 illustrates the highly significant (p < 0.01) interaction between the staking technique and variety with regard to marketable fruit production per hectare. As the result demonstrated in Fig. 1 below; Metadel variety with single-string staking (91.09 t ha− 1) and (96.97 t ha− 1) produced the highest marketable fruit yield. On the other hand, the lowest marketable yield was recorded from combinations of two treatments which is Eshet (29.71 t ha− 1) and (33.48 t ha− 1) with non-staking techniques and Miya (29.98 t ha− 1) and Miya (33.52 t ha− 1) were the second treatment combination that was reported as the lowest marketable fruit production, and they were statistically similar.

Metadel variety have a growth habit that aligns well with single-string staking. This method typically supports upright growth, allowing the plants to receive optimal sunlight and air circulation, which can enhance photosynthesis and overall growth. This staking method can enhance air circulation around the plants, reducing humidity and the risk of fungal diseases. By keeping the fruits off the ground, staking ensures that they are clean and undamaged and increases the amount of fruit that can be marketed. Fruit rot is avoided and high-quality fruits are produced by stakes. This guarantees that the foliage is better exposed to light for greater photosynthesis, improves aeration, and reduces the incidence of fungal illnesses28.Staking is advised by28 because it offers high-quality vegetables while shielding them from pests and animals. Figure 1 below illustrates marketable fruit yield of tomatoes.

Unmarketable fruit yield per hectare

Table 11 indicates that the interaction between variety and staking techniques was significant (p < 0.05) in the analysis of unmarketable fruit production per hectare. The results demonstrated that the treatment combinations of Miya varieties with non-staking conditions recorded the largest unmarketable fruit yield (45.49 t ha− 1) and (43.74 t ha− 1). On the other hand, the Metadel variety treatment combinations with single string staking (5.16 t ha− 1) and (6.75 t ha− 1) had the lowest unmarketable fruit output per hectare.

A study has shown that tomato plants grown without staking are more prone to fruit cracking due to exposure to direct sunlight and higher fruit temperatures. According to29, direct sunlight and high fruit temperatures reduce cuticle resistance and fruit firmness. A decrease in marketable yield owing to the incidence of Blossom end rot was also reported by30.

Total fruits yield per hectare

The yield of fruits per hectare was significantly affected (p < 0.01) by the interaction between variety and staking technique (Table 12). According to the results, a treatment combination of the Metadel variety with single string-staking produced the highest fruit yield per hectare in the first and second seasons, respectively, at (96.25 t ha− 1) and (103.72 t ha− 1). On the other hand, the lowest fruit yield was recorded from the treatment combination of variety (59.96 t ha− 1) and (63.27 t ha− 1) with non-staking.

The yield of tomatoes under different staking techniques can vary significantly, and comparing these yields to those reported in other regions with similar climates can provide valuable insights. Different staking techniques can significantly influence tomato yields, often resulting in higher outputs compared to non-staked plants. When comparing yields across regions with similar climates, methods like the Florida Weave and trellising tend to show favorable results, often yielding more than traditional practices. However, local conditions and management practices play a crucial role in determining actual yield outcomes. Tomato staking yields higher-quality, more valuable fruits with a higher market value. Staking reportedly enhances fruit yield by 18–25%26.

Economic analysis

To decide and recommend the best treatment combination from the study, it is necessary to know treatments with the highest net benefit. Economic analysis was performed following the CIMMYT partial budget methodology CIMMYT, 1988. It considers the analysis of gross benefit (GB), total variable cost (TVC), and net benefit (NB). The cost of staking materials, tomato seed and labor for management which varies across each treatment was considered a variable cost considering other costs as constant for each treatment. The gross benefit (GB) was calculated by multiplying yields by the corresponding price for each treatment. The total variable cost (TVC) (fertilizer including labor) for each treatment was calculated and added. Net benefit (NB) per hectare was calculated by deducting TVC per hectare from GB per hectare. The value of fruit yield was adjusted down by 10% to narrow the yield gap between experimental plots and farmer’s fields.

Partial budget analysis

The net profit for different staking techniques of tomato varieties Tables 13 and 14 showed that Metadel variety with single string staking gave the highest net profits of about 1,523,405 ETB and 1,634,537 ETB per hectare respectively. On the other hand, the lowest net profit was recorded from the treatment of a combination of Eshet with non-staking which is 561,469 ETB and 632,722 ETB per hectare in both seasons. This study suggested French type and single string staking to farmers as the cheapest methods of staking tomato plants as reported by Ariyarathne, (1989), Saunyama, and Knapp (2003) in their work on pruning and trellising which led to additional profits.

Conclusion and recommendations

In conclusion, seasonal variation did not show any significant differences in most of the growth and yield parameters. However, some variation was observed in the number of fruits per plant. Based on the results of the present experiment, Metadel with single string staking recorded the maximum fruit yield (96.25 t ha− 1) and (103.72 t ha− 1) in both seasons. In contrast, Metadel variety combined with single string staking gave maximum marketable yields of (91.09 t ha− 1) and (96.97 t ha− 1) in the first and second seasons, respectively. The partial budget analysis also showed that the interaction effect of staking and varieties were economically feasible as compared to the control treatment. The combination of Metadel with single string staking technique scored the highest net profit (1523405 ETB) and 1634537 ETB in both seasons respectively. On the other hand; the lowest net profit was recorded from a combination of Eshet with non-staked (561469 ETB) and 632722 ETB treatments respectively. Accordingly, applying a single-string staking technique with Metadel varieties is recommended for the economical production of tomatoes in northwestern Ethiopia and in areas with similar agro-ecology.

Therefore, farmers should conduct small-scale trials with various staking techniques to determine which best suits specific tomato varieties and local conditions. The government should invest in research to explore the effectiveness of various staking methods across different tomato varieties and environmental conditions. Moreover, the government should foster partnerships between universities and agricultural extension services to organize training sessions for farmers on optimal staking techniques and their benefits, including selected tomato varieties. By implementing these recommendations at both the farmer and government levels, stakeholders can significantly enhance the effectiveness of staking techniques for tomato varieties. These strategies will lead to improved yields, better quality produce, and more sustainable agricultural practices, ultimately benefiting farmers and contributing to food security. Implementing these recommendations for staking techniques can significantly enhance the growth and productivity of tomato varieties. By selecting the right methods, materials, and practices, growers can achieve healthier plants, higher yields, and improved fruit quality. Regular evaluation and adaptation of these practices will further support successful tomato cultivation. Implementing these recommendations for staking techniques can significantly enhance the growth and productivity of tomato varieties. By carefully selecting appropriate methods, durable materials, and effective practices, growers can achieve healthier plants, higher yields, and improved fruit quality. Additionally, regular evaluation and adaptation of these practices are essential for ensuring ongoing success in tomato cultivation. This proactive approach not only maximizes agricultural output but also contributes to sustainable farming practices.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the currently study available from the co-author on reasonable request.

References

Bekele, W., Atinafu, Y. & Chala, M. Performance evaluation and participatory variety selection of released tomato (Solanum Lycopersicon L.) varieties in West Shewa, Ethiopia. Perform. Evaluation, 12(1), 1–4 (2024).

Sifau, M. O. Genetic Diversity in Eggplant Solanum l. and Related Species from Southern Nigeria. (University of Lagos (Nigeria), 2014).

Hancock, J. F. Dispersal of New World Crops into the Old World, in World Agriculture before and after 1492: Legacy of the Columbian Exchange. 111–133 (Springer, 2022).

Kumar, A. et al. Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicon L.). Antioxidants in Vegetables and Nuts-Properties and Health Benefits. 191–207. (2020).

Faostat, F. Agriculture Organization Corporate Statistical Database.. 12 – 06. (2018).

Damte, T. Trends in pesticide use by smallholder farmers on ‘meher’season field and horticultural crops in Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Agricultural Sci. 32 (2), 133–156 (2022).

Woldeamlak. Current status and future opportunities of pepper production in Eritrea. ARPN J. Agricultural Biol. Sci. 8 (9), 655–672 (2021).

Jiang, C. et al. Responses of leaf photosynthesis, plant growth and fruit production to periodic alteration of plant density in winter produced single-truss tomatoes. Hortic. J. 86 (4), 511–518 (2017).

Ofori, P. A. et al. Greenhouse tomato production for sustainable food and nutrition security in the tropics. In Tomato-From Cultivation to Processing Technology ( IntechOpen, 2022).

Casal, J. J. Canopy Light Signals and Crop Yield in Sickness and in Health. (International Scholarly Research Notices, 2013).

Gutierrez, E. E. V. An overview of recent studies of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum spp) from a social, biochemical and genetic perspective on quality parameters. Basic. Microbiol. 50, 211–217 (2018).

Hilmi, M. Tomato Marketing in Developing Economies. (Rome, 2022).

Alemu, D. & Thompson, J. The emerging importance of rice as a strategic crop in Ethiopia. In Agricultural Policy Research in Ethiopia (APRA), A Working Paper, 44 (2020).

Gomez, E., Corea, C. & Gadd, S. Gomez (Denon, 1984).

Abebe, S. A. Application of time series analysis to annual rainfall values in Debre Markos town, Ethiopia. Comput. Water Energy Environ. Eng. 7 (03), 81 (2018).

Ertop, M. H. & Bektaş, M. Enhancement of bioavailable micronutrients and reduction of antinutrients in foods with some processes. Food Health. 4 (3), 159–165 (2018).

Patil, V., Gangaprasad, S. & Kumar, D. Studies on variability, heritability, genetic advance and transgressive segregating in Brinjal (Solanum melongena L). Pharma Innov. J. 10 (8), 1763–1766 (2021).

Geilfus, C. M. & Geilfus, C. M. Drought stress. In Controlled Environment Horticulture: Improving Quality of Vegetables and Medicinal Plants. 81–97. (2019).

Islam, S., Hassan, L. & Hossain, M. A. Breeding potential of some exotic tomato lines: A combined study of morphological variability, genetic divergence, and association of traits. Phyton 91 (1), 97 (2022).

Reddy, S. V. et al. Genetic variability, heritability and correlation studies on tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L). J. Pharmacognosy Phytochemistry. 8 (4), 2465–2470 (2019).

Weng, L. et al. The zinc finger transcription factor SlZFP2 negatively regulates abscisic acid biosynthesis and fruit ripening in tomato. Plant Physiol. 167 (3), 931–949 (2015).

Emami, A. & Eivazi, A. R. Evaluation of genetic variations of tomato genotypes (Solanum lycopersicum L.) with multivariate analysis. Int. J. Sci. Res. Environ. Sci. 1 (10), 273 (2013).

Hasan, M. et al. Adaptibility of tomato genotypes suitable for coastal region of Patuakhali in Bangladesh. Progressive Agric. 28 (2), 84–91 (2017).

Gojeh, A. J. Yield and Guality of Indeterminate Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicon L.) Varieties vvith Staking Methods in Jimma. (2012).

Lamptey, S. & Koomson, E. The Role of Staking and Pruning Methods on Yield and Profitability of Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum L.) Production in the Guinea Savanna Zone of Ghana. Vol. 1. 5570567 (Advances in Agriculture, 2021).

Alam, M. et al. Effect of Different Staking Methods and Stem Pruning on Yield and Quality of Summer Tomato. (2016).

Regassa, M. D., Mohammed, A. & Bantte, K. Evaluation of tomato (Solanum Lycopersicon L.) genotypes for yield and yield components. Afr. J. Plant. Sci. Biotechnol. 6 (1), 45–49 (2012).

Rashid, M. Improving growth, yield and quality of Cherry tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) using staking and mixed fertilization. J. Agric. Food Environ. (JAFE). 3 (3), 77–85 (2022). ISSN (Online Version): 2708–5694.

Romero, P. & Rose, J. K. A relationship between tomato fruit softening, cuticle properties and water availability. Food Chem. 295, 300–310 (2019).

Gebremariam, M. & Tesfay, T. Optimizing irrigation water and N levels for higher yield and reduced blossom end rot incidence on tomato. Int. J. Agron. 2019, 1–10 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the tomato cultivars provided by the Fogera Research Center and Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR). Finally, I would like to acknowledge the paper Amina Jatau Gojeh for using as guideline ‘‘Effect of different Staking methods on yield and quality of indeterminate Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicon L.)) varieties under jimma condition, Ethiopia”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yibeltal Wubetie conducted the concept, design, data analysis (software analysis), interpretation, and final write-up of the manuscript. Abayneh Wubetu also contributed to the comments and conceptualization of this paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wubetie, Y., Wubetu, A. Effects of staking techniques on growth and yield of tomato varieties in northwestern Ethiopia. Sci Rep 15, 20011 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95659-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95659-7