Abstract

Animals need to recognize different individuals, both con- and heterospecifics, to make appropriate decisions. In the wild, responses to familiar individuals may vary depending on the context, which can be beneficial. However, differing responses towards human experimenters can influence experimental outcomes. Such effects might be particularly overlooked in reptiles which are frequently viewed as cognitively less advanced. We tested Tokay geckos’ (Gekko gecko) ability to distinguish between familiar and unfamiliar handlers in two situations: in a novel situation (exerting physical constraint) and a routine situation (feeding from forceps as during regular husbandry). Geckos showed sex-specific differences towards familiar and unfamiliar handlers in a routine situation, but not in a novel situation, in which they showed individual repeatability. Our results further advance our understanding of reptile cognition revealing important insights into context specific responses in relation to handler identity with implications for experimental animal studies that are rarely considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To be able to behave appropriately during interactions with members of the same or different species, animals need to discriminate among different individuals (e.g. familiar versus unfamiliar, kin versus non-kin, or single individuals)1. Importantly, behaviour towards familiar individuals might be specific to the context in which they are encountered. For example, male rhesus monkeys’ (Macaca mulatta) support in agonistic interactions depends both on the identity and relative dominance status of the receiver and the aggressor2. Moreover, ants (Formica xerophila and F. integroides) can behave differently towards heterospecific neighbours and strangers based on resource value. They show more aggression towards strangers within their general territory, but similar amounts of aggression towards both when near their nest3. Even though context dependent responses towards different individuals can be crucial in the wild, similar context specificity might, however, be detrimental for experimental outcomes.

Research worldwide is currently facing a reproducibility crisis, in which the findings of previous scientific studies are challenging or impossible to replicate4. Given that reliable, high quality results are critically important for scientific advancement, there is an urgent need to identify the root causes of this lack of reproducibility to reduce potential sources of variation. Recently, it has been shown that the subjectivity involved in data analysis can lead to vastly different results5. However, even if statistical analyses become more standardized, underlying issues might persist, potentially arising at any stage of a project. In studies with animals, the sampling and study design, such as where and how individuals are collected, the acclimation period to the procedures or laboratory, past experiences, the occurrence or level of environmental enrichment and change, can impact the behaviour of animals during experiments and thus produce altered experimental results6,7,8,9,10. Importantly, researcher identity might also create behavioural differences that are not promoted by or linked to the experimental question/ investigation itself9,11. For example, unfamiliarity with the experimenter increases anxiety scores in laboratory rats9. Given that many animals across taxa can distinguish between human individuals12, it is surprising that this aspect is often overlooked in experimental settings, and its impact on results should not be neglected.

Some animal species can recognize and discriminate specific human faces or human individuals. Captive fishes can recognize many different human faces displayed on a virtual screen (in archerfish, Toxotes chatareus)13, and differentiate between two human caretakers that perform different husbandry tasks (in zebrafish, Danio rerio)14. Similarly, corn snakes (Pantherophis guttata) can distinguish between a familiar handler and a stranger, when living in enriched environments8. Research has also shown that some animals adjust their behaviour according to the perceived threat level associated with different individuals. For example, some bird species known for their cognitive abilities, such as wild jackdaws (Corvus monedula)15, wild Antarctic brown skuas (Stercorarius antarcticus)16,17, captive black-billed magpies (Pica pica)9, wild Northern mockingbirds (Mimus polyglottos)18 and wild American crows, (Corvus brachyrhynchos)19 can discriminate between threatening and non-threatening humans, and adjust their mobbing behaviour to directly target threatening individuals. Thus, it is likely that many captive animals can at least distinguish their caretakers or familiar experimenters from strangers12 and that this might exert an impact during experiments9,11. In order to account for potential variation caused by differences in behaviour towards handlers, it is crucial to assess whether some contexts/ circumstances allow animals to identify/ discriminate handlers but also whether consequent behaviour adjustments are context related/ specific.

In addition to the conceptual gap of knowledge, we emphasize a taxonomic bias in the existing literature. Indeed, the effects of experimenter identity have only been investigated in mammals and birds9,11,20. This bias might stem from the misconception according to which reptiles are still perceived as strongly driven by innate behaviours rather than complex cognition21,22,23. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to understand if captive Tokay geckos (Gecko gecko) would behave differently towards familiar and unfamiliar handlers depending on the context: in a novel and a routine situation. Tokay geckos are a facultative social lizard species that forms temporary family groups, showing pair-bonding and parental care24, which requires them to be able to discriminate at least their mate and offspring among conspecifics. Indeed, they can discriminate familiar from unfamiliar mates based on odour25 and their own odour from that of an unfamiliar same-sex conspecifics26. Therefore, we expect them to have the sensory capacity to discriminate at least categories (familiar versus unfamiliar) of human handlers.

To simulate a novel situation, we induced tonic immobility, a procedure that the individuals in our study never experienced before. Tonic immobility is induced by constraining an animal on its back and applying pressure to the spine27, which triggers the animal to enter a state in which it appears to be dead for some time, after which it returns to its normal activity28. This anti-predator behaviour aims to distract a predator so it loses interest in the prey aiding its escape29. When employing tonic immobility, lizards can evaluate the threat level of the situation and adjust this strategy accordingly30,31,32. Therefore, the novel situation had a negative valence. To simulate a routine situation, we presented live prey in forceps as during geckos’ usual husbandry procedure. Therefore, the routine situation had a positive valence. We hypothesised that (1) if geckos cannot discriminate between handlers, they would behave similarly towards unfamiliar and familiar researchers across situations. (2) If they can discriminate handlers and base their behaviour on previous knowledge with the handlers but ignore their experience with or the valence of the situation (novel/ negative or routine/ positive), they would behave differently towards unfamiliar and familiar researchers in both situations. (3) If they can discriminate handlers and also base their behaviour on previous experience with or the valence of each situation (novel/ negative or routine/ positive ), they would show context-dependent behaviour and behave similarly towards unfamiliar and familiar researchers in the novel situation (mismatch between handler and context familiarity), but behave differently in the routine situation (match between handler and context familiarity).

Our results support our third hypothesis: in the novel situation, geckos responded similarly across handlers (with high individual repeatability across repetitions) whereas in the routine situation geckos differentiated across handlers depending on handler sex and handler familiarity. Moreover, female lizards were less likely and took the longest to attack prey presented by an unfamiliar male handler. They also showed no difference in the probability, but longer latency, to attack prey presented by the unfamiliar female handler compared to the familiar female handler. Contrary, male lizards’ probability to attack prey did not differ across handlers but they took longer to attack prey presented by the unfamiliar male handler compared to the familiar female handler, while latency to attack did not differ between female handlers.

Materials and methods

Our reporting follows the recommendations as laid out by the ARRIVE guidelines33.

Animals

In the novel situation (tonic immobility), we tested 14 adult, captive bred Tokay geckos (7 males: Snout-to-vent length (SVL) range = 14.45–15.99 cm, 7 females: SVL range = 12.97–14.61 cm)24, and in the routine situation (feeding from forceps) we tested 39/37 captive bred geckos (unfamiliar male handler: 16 males: SVL range = 12.25–15.99 cm, 23 females: SVL range = 11.76–14.91 cm; unfamiliar female handler: 16 males: SVL range = 12.25–15.99 cm, 21 females: SVL range = 11.76–14.91 cm) including the 14 adults used in the tonic immobility test. We were unable to test more than 14 individuals in the tonic immobility test due to time constraints. 22 individuals were purchased from different breeders, while 17 were bred from these adult individuals in our facility. Geckos were between 2 and 8 years of age at the time of the study. Sex of individuals was determined based on the presence (male) or absence (female) of femoral glands24.

Captive conditions

All gecko enclosures are equipped with a compressed cork wall screwed to the back and enriched with live plants. We provide cork refuges (cork branches cut in half, hung on the back wall with hooks) as well as branches for climbing. Enclosures are set-up bioactive. They contain a drainage layer of expanded clay on the bottom, covered with mosquito mesh (to prevent mixing of the expanded clay and the soil) and topped with organic rainforest soil (Dragon BIO-Ground). Additionally, we spread autoclaved red oak leaves and sphagnum moss on top of the soil to provide shelter and food for the isopods and earth worms that break down the faecal matter produced by the geckos. Enclosures are made of rigid foam slabs with a mesh top and glass front doors.

We keep enclosures across three rooms on shelves with small enclosures on the top and large enclosures on the bottom (we tested all 11 individuals from one room and three from the second room in the novel situation and all individuals in the routine situation). The environment in the rooms is fully controlled by an automatic system that aims to mimic natural conditions. Geckos are kept under a reversed 12 h:12 h photo period (light: 6pm to 6am, dark: 6am to 6pm). A red light (PHILIPS TL-D 36 W/15 RED) not visible to geckos34 ensures that researchers are able to work with the geckos during the “night” when they are active. The system simulates sunrise and sunset. The day/ night changes are accompanied by a change in room temperature from approximately 25 °C during the night to about 31 °C during the day. During the day, we also provide UVB (Exo Terra Reptile UVB 100, 25 W) light from directly above the enclosures. A heat mat (TropicShop) fixed to the right outside wall of each enclosure increases the temperature locally by 4–5 °C and allows lizards to thermoregulate to their optimal body temperature at any time. Base room humidity is kept at 50% but 30s of daily rainfall with reverse osmotic water approximately every 12 h (at 5pm and 4am) increases the humidity within enclosures to 100% for a short period of time.

During the first three trials of the novel situation, three female geckos were kept singly in terraria of the size 45 L x 45 B x 70 H cm, one male was kept singly in a terrarium of the size 90 L x 45 B x 100 H cm and the other eight individuals were kept in pairs in terraria of the size 90 L x 45 B x 100 H cm. During the last trial, all except two individuals (G011 and G020) were housed singly (females: 45 L x 45 B x 70 H cm; males: 90 L x 45 B x 100 H cm). During the routine situation, 30 individuals were kept in pairs in terraria of the size 90 L x 45 B x 100 H cm, one male and one female were kept singly in a terrarium of the size 90 L x 45 B x 100 H cm and the remaining 7 females were kept in terraria of the size 45 L x 45 B x 70 H cm.

Husbandry

We feed geckos with either 3–5 adult house crickets (Acheta domesticus), mealworms (Tenebrio molitor) and/ or cockroaches (Nauphoeta cinerea), three times per week on Monday, Wednesday and Friday individually, using 25 cm long forceps. Prior to feeding, insects are fed with cricket mix (various brands), high protein dry cat food (various brands), fresh carrots and apples to ensure that they provided optimal nutrition (Vitamin D and calcium). In gecko enclosures, water is provided ad libitum in a water bowl. To keep track of lizards’ health, we weigh (± 1 g) them once a month and measure their snout vent length (± 0.5 cm) approximately every three-four months.

Tonic immobility (novel situation)

Experimental set-up

Tonic immobility was induced inside an empty glass testing tank (45 L x 45 B x 60 H cm) with a mesh top (Exo Terra Glass tank). The testing tank was placed inside the gecko rooms on a table ensuring the same basic climatic conditions during testing as provided under normal housing. All sides, except for the doors and mesh top, were wrapped in black plastic to make them opaque. Lizards were tested under red light and a piece of cardboard was placed on the floor of the testing tank to prevent lizards from losing body heat. The testing tank was placed so that the transparent doors were facing away from the room door. Trials were recorded from above using a Samsung S20 smartphone (108 Megapixel, 8 K-FUHD) or a GoPro Hero 8 Black (linear mode, 1080 resolution, 24 FPS) placed on the mesh top of the testing tank. We ran four trials per individual for a total of 56 trials.

Experimental procedures. Experiment 1, tonic immobility (novel situation): White circles on the ventral area of the individual indicate the five locations at which the lizard was held by the handler during the induction of tonic immobility in all trials. Each gecko was tested four times, one month apart, by unfamiliar (trial 1 and 3, by two different researchers) and familiar handlers (trial 2 and 4, same researcher). Each lizard was allowed 15 min to upright. Experiment 2, feeding from forceps (routine situation): Geckos were fed with forceps by a familiar and unfamiliar handlers (different days) and given 30 s to complete the trial.

Procedure

First, a lizard was captured by hand (opening the tank, locating the individual and capture - duration on average 2–3 min) from within its home enclosure by one researcher (trial 1: BS, trial 2: LB, trial 3: LB, trial 4: LB) and then handed to a second researcher who would induce tonic immobility (trial 1: IDM - unfamiliar, trial 2: BS - familiar, trial 3: ER - unfamiliar, trial 4: BS – familiar; Fig. 1). All researchers involved in the study were female, experienced in the capture of geckos and with prior training on inducing tonic immobility in Tokay geckos. Next, the lizard was turned on its back (head facing to the left from the handler’s perspective) within the testing tank on top of the piece of cardboard and the video recording was started. For the next 45 s the lizard was held on its back, left hand flat over its head and front legs, while the hind legs (thighs, Fig. 1, position 4 and 5) were gently held down with two fingers of the researchers’ right hand. Thereafter, the experimenter changed the position of their left hand putting the pinkie finger on the lizards’ chin (Fig. 1, position 1), and the thumb and index finger on the lizards’ shoulders (Fig. 1, position 1 and 2). All other fingers were stretched out to prevent the gecko from holding on with their pads. The lizard was gently held down in this position for the remaining 75 s (until a total of 2 min had elapsed). At this point, the experimenter removed their hands, closed the testing tank doors, locked them and moved away always to the right in the direction of the lizards’ tail (see supplementary video M1 for the whole procedure). If the lizard did not stay on its back, the experimenter resumed induction as described above until tonic immobility was induced. Individuals were given a trial of 15 min to upright themselves. At the end of the trial, lizards were captured by hand and released back into their home enclosure. If a lizard had not righted itself at the end of a trial its right hind leg was gently touched to induce righting, before being transported back into its enclosure.

The researcher who induced tonic immobility washed their hands thoroughly with soap between lizards and the cardboard was either flipped or replaced each trial to avoid odour cues from other individuals influencing tonic immobility. Lizards were tested between 07:30 h and 14:00 h in a random order between each trial (inter-trial interval of approximately one month). We made sure not to test two lizards from the same enclosure consecutively. All geckos used in this experiment were naïve to the procedure, however, half of the geckos (4 males and 3 females) performed another behavioural experiment between trials 2–3 and 3–4 (scan sampling of spatial behaviour35; chemical mate recognition25). All trials were conducted between December 2022 and March 2023.

Data collection

Videos were scored using the behavioural coding software BORIS36. We scored the latency to induce tonic immobility in seconds, from the moment an individual was first held down using all five locations on its body until the trial start (closing of the testing tank doors). We also scored if uprighting occurred (yes = 1, no = 0) and the time taken (seconds) from trial start (closing of the testing tank doors) until an individual uprighted (duration of immobility). All latencies were scored to an accuracy of 1 s. Additionally, we scored if a tail movement occurred (yes/ no; movement of the tail in a curling manner performed as an antipredator display37) and which side the individual used to upright itself (left or right, side closest to the ground when turning). We used the moment the lizard had half turned around as the endpoint of the trial. If lizards did not upright within 15 min, they received a truncated duration of immobility of 900 s, occurrence of 0 and side to upright as NA. Using the side each lizard turned across the four trials, we calculated a laterality index as (\(\:\frac{{N}_{right}}{{N}_{left}+{N}_{right}}\)) for each individual. In addition, for each trial, we recorded room temperature (measured within 5 min of trial start), and lizards’ weight (closest measure in time to the date of the trial) and snout vent length (average across the experimental period).

Inter-observer reliability

We were unable to score videos blind as to animal identity. Therefore, 50% of videos were scored by two independent observers (one trial = 25% of videos each). Scores across observers were highly consistent (Trial 1: Spearman rank correlation, Rturning latency = 1, pturning latency < 2.2*10−16; Rlatency to induce = 0.96, platency to induce < 5.3*10−8; Cohen’s Kappa, koccurance = 1, Noccurance = 14; kside = 1, Nside = 10; ktail = 1, Ntail = 14; Trial 4: Spearman rank correlation, Rturning latency = 0.99, pturning latency < 2.2*10−16; Rlatency to induce = 0.99, platency to induce < 4*10−13; Cohens Kappa, koccurance = 1, Noccurance = 14; kside = 1, Nside = 8; ktail = 0.87, Ntail = 8).

Feeding from forceps (routine situation)

Experimental set-up

Lizards were tested within their home enclosure on two feeding mornings (between 9:00 and 11:00 am). Beforehand, we randomly split lizards into two groups, one was first tested by the familiar handler (BS), while the other half was tested by unfamiliar handlers (PG and LF): an unfamiliar male handler (21st and 23rd of January 2024) and an unfamiliar female handler (31st of July and 2nd of August 2024), respectively. The order of testing was reversed on the following test day. Consequently, all lizards received four trials (two by the familiar and one by each unfamiliar handler). Furthermore, within a day, lizards were tested in a random order. The unfamiliar handlers received prior training (one day) on how to feed and perform video recordings of gecko behaviour.

Procedure

At the start of the test, a dim white light (LED, SPYLUX® LEDVANCE 3000 K, 0.3 W, 17 lm), that lizards were accustomed to (used during regular husbandry), was placed on top of the tank. Next, a focal lizard was located within its enclosure. If necessary, cork shelters were gently removed to be able to take video recordings. Once the focal individual was visible, a video recording was started using a Samsung S20 smartphone (108 Megapixel, 8 K-FUHD). Then, a live cockroach was presented to the individual within 4–5 cm in front of its snout using 25 cm long forceps (Fig. 1; see supplementary video M1). The behaviour of the lizard was recorded either until an attack occurred, it walked away or did not respond for 30s (this time was deemed appropriate as lizards usually attack prey immediately). Each handler was alone in the room while performing the experiment. All geckos used in this study had previously participated in a neophobia experiment in which prey was presented in forceps (with or without an object attached) similar to the current study38.

Data collection

Videos were scored using the behavioural coding software BORIS36. We measured the time from when the lizard first noticed a food item until the first attack regardless of whether the food was captured or not (latency) as well as its occurrence (yes = 1 and no = 0). We assumed that a food item was first noticed when a lizard moved its head or eyes to focus on the prey38. Lizards that did not attack the prey within 30s were given a latency of 22 s (longest latency + 1 s) for easier plotting of the results. In addition, for each trial, we recorded enclosure temperature, and lizards’ weight (closest measure in time to the date of the trial) and snout vent length (average across the experimental period).

Inter-observer reliability

Even though the handler was not visible in the videos, we were unable to score videos blind as to animal identity. Therefore, 50% of videos were scored by two independent observers. Scores across observers were highly consistent (Spearman rank correlation, Rlatency = 0.971, platency < 2.2*10−16; Cohen’s Kappa, koccurance = 1, Noccurance = 75).

Statistics and reproducibility

Tonic immobility (novel situation)

Data from seven male and seven female geckos tested across four repetitions (performed by one familiar and two unfamiliar handlers) was used. First, we investigated if the probability of uprighting (Bernoulli variable, turn = 1, no turn = 0) was influenced by the fixed effects of sex (male, female), the latency to induce tonic immobility, if tail movement occurred (yes = 1, no = 0), handler familiarity (familiar - BS, unfamiliar - IDM & ER), room temperature (degree Celsius) and the body condition of the lizard (scaled mass index39). Originally, we also included the interaction between handler familiarity and the latency to induce tonic immobility in the model but because we found no evidence for an interaction, it was removed to ensure better model performance. We used a Bayesian generalised linear mixed model (GLMM) with a Bernoulli distribution from the package brms40,41,42 with random effects of animal identify (intercept) and trial (1–4, slope).

Second, we investigated if the duration of immobility (log-normal variable) was influenced by the fixed effects of handler familiarity, sex, the latency to induce tonic immobility, if tail movement occurred, room temperature and the body condition of the lizard. In this model, we also removed the interaction between handler familiarity and the latency to induce tonic immobility to ensure better model performance. Because the duration of immobility measure was censored (cut off at 900 s), we used a censored Bayesian GLMM with a log-normal distribution and random effects of animal identify (intercept) and trial (slope).

Third, we investigated if the probability of uprighting to the right (Bernoulli variable, right turn = 1, left turn = 0) was influenced by the fixed effects of handler familiarity, sex, room temperature and the body condition of the lizard. Again, we used a Bayesian GLMM with a Bernoulli distribution and random effects of animal identify (intercept) and trial (slope).

Finally, we investigated agreement repeatability in the duration of immobility using the package rptR43. We log-transformed the duration of immobility to fit a normal distribution. We calculated individual repeatability from the whole dataset and after removal of trials in which a lizard did not upright (with a censored latency of 900 s) as we wanted to know if the truncated trials would bias repeatability. Due to the small sample size, we did not calculate individual repeatability in the probability of uprighting and the side to upright.

Feeding from forceps (routine situation)

Data from 16 male and 23/ 21 female geckos tested across four repetitions (performed by one familiar and two unfamiliar handlers) was used. First, we investigated if the probability of attacking prey (Bernoulli variable, eaten = 1, not eaten = 0) was influenced by the fixed effects of lizard sex (male or female), handler familiarity (familiar - BS, unfamiliar - PG & LF), repetition (1 to 4), enclosure temperature and the body condition of the lizard. We included the interaction between handler familiarity and sex, which was further analysed using post hoc least squares means tests (LSM, package emmeans44). We used a Bayesian GLMM with a Bernoulli distribution and a random effect of animal identify (intercept). Because we found a difference in response between familiar and unfamiliar handlers, we ran a second model to investigate if responses were specific to the handlers. We used the probability of attacking prey as the response variable, and handler identity (BS [familiar female], PG [unfamiliar male] and LF [unfamiliar female]) in interaction with lizard sex, as well as enclosure temperature (which showed an effect in the first model) as the fixed effects. Thereafter, the results of the interaction were further analysed using post hoc least squares means tests.

Second, we investigated if the latency to attack (log-normal variable) was influenced by the fixed effects handler familiarity, lizard sex, repetition, enclosure temperature and the body condition of the lizard. Again, we included the interaction between handler familiarity and sex, which was further analysed using post hoc least squares means tests. Because the trials were censored (cut off at 30 s), we used a censored Bayesian GLMM with a log-normal distribution and a random effect of animal identify (intercept). Here again, we found an effect of handler familiarity. Therefore, we ran a second model with the latency to attack as the response variable, and handler identity in interaction with lizard sex, as well as temperature as the fixed effects. The results of the interactions were further analysed using post hoc least squares means tests.

All analyses were run in R version 4.2.245. For all Bayesian models, we ensured that Rhat was 1, that the ESS was above 2000 and checked the density plots and correlation plots to ensure that the models had sampled appropriately. We used a diffuse normal prior with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. We used a test for practical equivalence to determine whether to accept or reject a “null hypothesis”, formulated as “no difference” or “no relationship”, for each fixed effect in a model using the equivalence_test function from the package bayestestR46. We report results in which the null hypothesis was accepted (100% within the Region of Practical Equivalence – ROPE) or was undecided as no evidence and results in which the null hypothesis was rejected (0% within the ROPE) as evidence. Additionally, we provide Bayes factors (BF) to further evaluate the results by determining Bayes Factors from marginal likelihoods using the package brms or Bayes Factor pairwise comparisons from the package pairwiseComparisons47 where appropriate. Bayes factors below 1 indicate more support for no difference while above 1 more support for a difference48. We report cases in which the equivalence test produced “undecided” results but Bayes factors were above 1 as evidence.

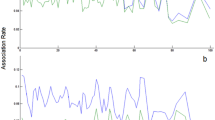

Experiment 1 on tonic immobility (novel situation) - Duration of immobility after handling by familiar and unfamiliar researchers, and individual gecko consistency in this behaviour. (a) Boxplots of the duration of immobility (grey points represent the individual average per treatment) between trials in which a familiar (BS) and an unfamiliar handler (IDM and ER) induced tonic immobility. The bold line shows the median, the upper and lower edge of the boxes shows the upper and lower quartile, respectively, and the top and bottom edge of the whisker shows the maximum and minimum, respectively. (b) Individual behavioural consistency over the four trials (ordered by mean latency for visual purposes). Open circles represent raw data from each trial, closed circles represent individual mean, and black vertical lines show individual variation. For both (a) and (b) we tested 7 females and 7 males.

Results

Tonic immobility (novel situation)

We were able to induce tonic immobility in all geckos, across all 56 trials. We found no evidence for the probability of uprighting to differ between familiar and unfamiliar handlers (GLMM, estimateunfamiliar = 0.796, 95% CIlow = −0.790, 95% CIup = 2.431, 12.19% inside ROPE, BF = 0.701). Moreover, we found no evidence that the probability of uprighting was associated with temperature (GLMM, estimate = −0.469, 95% CIlow = −1.654, 95% CIup = 0.645, 19.05% inside ROPE, BF = 0.825), body condition (GLMM, estimate = −0.007, 95% CIlow = −0.184, 95% CIup = 0.167, 99.91% inside ROPE, BF = 0.090), sex (GLMM, estimatemale = −0.076, 95% CIlow = −1.854, 95% CIup = 1.701, 16.27% inside ROPE, BF = 0.251), if tail movement occurred (GLMM, estimateyes = −0.422, 95% CIlow = −1.990, 95% CIup = 1.207, 16.06% inside ROPE, BF = 0.926) or with the latency to induce tonic immobility (GLMM, estimate = −0.023, 95% CIlow = −0.055, 95% CIup = 0.003, 100% inside ROPE, BF = 0.061).

Similarly, we found no evidence that the duration of immobility differed between familiar and unfamiliar handlers (GLMM, estimateunfamiliar = −0.627, 95% CIlow = −1.655, 95% CIup = 0.376, 0.89% inside ROPE, BF = 0.349; Fig. 2a). Furthermore, we found no evidence that the duration of immobility was associated with temperature (GLMM, estimate = −0.198, 95% CIlow = −0.916, 95% CIup = 0.418, 2.51% inside ROPE, BF = 0.320), body condition (GLMM, estimate = 0.028, 95% CIlow = −0.045, 95% CIup = 0.105, 18.03% inside ROPE, BF = 0.050), sex (GLMM, estimatemale = 0.522, 95% CIlow = −0.945, 95% CIup = 1.931, 0.96% inside ROPE, BF = 0.232), or the latency to induce tonic immobility (GLMM, estimate = 0.008, 95% CIlow = −0.001, 95% CIup = 0.018, 67.24% inside ROPE, BF = 0.020). However, we found evidence that the probability that tail movement occurred was higher when individuals took longer to uprighten themselves (GLMM, estimateyes = 0.675, 95% CIlow = −0.192, 95% CIup = 1.533, 0.58% inside ROPE, BF = 1.429).

We found evidence for individual agreement repeatability of the duration of immobility of R = 0.414 (CIlow = 0.15, 95% CIup = 0.74; Fig. 2b). Similarly, after removal of trials in which lizards did not upright, we still found evidence for individual agreement repeatability in the duration of immobility of R = 0.555 (CIlow = 0.086, 95% CIup = 0.815).

We found no evidence that the probability of uprighting to the right side was associated with temperature (GLMM, estimate = 0.043, 95% CIlow = −0.860, 95% CIup = 0.945, 32.65% inside ROPE, BF = 0.461), or body condition (GLMM, estimate = 0.031, 95% CIlow = −0.061, 95% CIup = 0.136, 100% inside ROPE, BF = 0.056), nor did it differ between males and females (GLMM, estimatemale = −0.408, 95% CIlow = −1.791, 95% CIup = 0.986, 18.04% inside ROPE, BF = 0.437) or familiar and unfamiliar handlers (GLMM, estimateunfamiliar = −0.586, 95% CIlow = −2.061, 95% CIup = 0.925, 14.12% inside ROPE, BF = 0.312). Some of the lizards showed a side bias when uprighting (Table 1).

Feeding from forceps (routine situation)

Overall, we found that geckos responded differently to familiar and unfamiliar handlers. Moreover, we found evidence for more than five times stronger support for a difference in female geckos (LSM, estimatefam−unfam = 1.260, 95% CIlow = 0.250, 95% CIup = 2.250, 0% inside ROPE, BF = 5.588), while we only found weak evidence in males (LSM, estimatefam−unfam = 1.050, 95% CIlow = −0.333, 95% CIup = 2.550, 4.37% inside ROPE, BF = 1.162). We found no evidence for the probability to attack prey to be related with the order of testing (familiar or unfamiliar handler first; GLMM, estimate = −0.266, 95% CIlow = −1.177, 95% CIup = 0.644, 28.42% inside ROPE, BF = 0.537) or body condition (GLMM, estimate = 0.021, 95% CIlow = −0.017, 95% CIup = 0.062, 100% inside ROPE, BF = 0.033). However, we found weak evidence that enclosure temperature had an effect (GLMM, estimate = 0.615, 95% CIlow = −0.011, 95% CIup = 1.304, 7.48% inside ROPE, BF = 1.688).

Our analysis regarding handler identity revealed over nine times stronger support for a difference in the probability to attack between the familiar female and unfamiliar male handler in female geckos (LSM, estimateBS−PG = 1.718, 95% CIlow = 0.623, 95% CIup = 2.806, 0% inside ROPE, BF = 9.456; Fig. 3a); less females attacked prey when tested by an unfamiliar male handler. Similarly, we found more than five times stronger support for a difference in the probability to attack between the unfamiliar female and unfamiliar male handler (LSM, estimatePG−LF = −1.724, 95% CIlow = −3.238, 95% CIup = −0.234, 0% inside ROPE, BF = 5.238; Fig. 3a); again, less females attacked prey when tested by an unfamiliar male handler. However, we found no evidence that female lizards’ probability to attack differed between the familiar female and unfamiliar female handler (LSM, estimateBS−LF = −0.016, 95% CIlow = −1.251, 95% CIup = 1.226, 13.58% inside ROPE, BF = 0.771; Fig. 3a). Contrary to females, we found very weak or no evidence that males probability to attack differed between handlers (LSM, estimateBS−PG = 1.344, 95% CIlow = −0.249, 95% CIup = 2.880, 2.65% inside ROPE, BF = 1.042; estimateBS−LF = 0.282, 95% CIlow = −1.525, 95% CIup = 2.015, 8.34% inside ROPE, BF = 0.835; estimatePG−LF = −1.052, 95% CIlow = −3.230, 95% CIup = 1.046, 4.76% inside ROPE, BF = 0.813; Fig. 3a). Finally, we found no evidence in the simpler model for an effect of temperature on the probability to attack (GLMM, estimate = 0.254, 95% CIlow = −0.457, 95% CIup = 0.984, 33.06% inside ROPE, BF = 0.459).

Feeding from forceps (routine situation) - Feeding behaviour towards prey presented by familiar and unfamiliar handlers. (a) Percentage of individuals that attacked the prey presented by the familiar handler (BS) and the unfamiliar male (PG) and female handlers (LF). Individuals that attacked and ate the prey are represented in solid lines with darker colour, and those that did not attack are represented in dashed lines. (b) Boxplots of the latency to attack the prey (grey points represent the individual data points) between trials in which a familiar (BS) and unfamiliar handlers (male PG and female LF) presented a prey. Females are represented in beige and males in dark grey. The bold line shows the median, the upper and lower edge of the boxes shows the upper and lower quartile, respectively, and the top and bottom edge of the whisker shows the maximum and minimum, respectively. For both (a) and (b) we tested 23 females and 16 males with an unfamiliar male handler and 21 females and 16 males with an unfamiliar female handler.

Similar to the probability to attack, we found evidence that geckos showed different responses towards familiar and unfamiliar handlers. We found evidence for more than 34 times more support for a difference in female geckos (LSM, estimatefam−unfam = −0.817, 95% CIlow = −1.268, 95% CIup = −0.353, 0% inside ROPE, BF = 34.278), and more than twice as much support for a difference in males (LSM, estimatefam−unfam = −0.471, 95% CIlow = −0.991, 95% CIup = 0.044, 5.78% inside ROPE, BF = 2.106). Again, we found no evidence that the order of testing (familiar or unfamiliar handler first; GLMM, estimate = 0.051, 95% CIlow = −0.300, 95% CIup = 0.408, 5.01% inside ROPE, BF = 0.190) or body condition (GLMM, estimate = −0.003, 95% CIlow = −0.021, 95% CIup = 0.014, 74.86% inside ROPE, BF = 0.010) were related to the latency to attack prey. However, we found over six time more support that enclosure temperature was correlated with the latency to attack (GLMM, estimate = −0.342, 95% CIlow = −0.576, 95% CIup = −0.104, 0% inside ROPE, BF = 6.612).

Our analysis regarding handler identity revealed over 42 times stronger support for a difference in the latency to attack when prey was presented by a familiar female compared to an unfamiliar male handler in female geckos (LSM, estimateBS−PG = −1.419, 95% CIlow = −2.000, 95% CIup = −0.876, 0% inside ROPE, BF = 42.772; Fig. 3b); females took longer to attack when prey was presented by an unfamiliar male handler. Furthermore, we found more than seven times stronger support for a difference in the latency to attack when prey was presented by an unfamiliar female compared to an unfamiliar male handler (LSM, estimatePG−LF = 1.240, 95% CIlow = 0.498, 95% CIup = 1.940, 0% inside ROPE, BF = 7.500; Fig. 3b); again, females took longer to attack when prey was presented by an unfamiliar male handler. We found no evidence that female geckos took longer to attack when prey was presented by an unfamiliar female compared to a familiar female handler (LSM, estimateBS−LF = −0.175, 95% CIlow = −0.703, 95% CIup = 0.351, 234.84% inside ROPE, BF = 0.863; Fig. 3b). In male geckos, we found almost twice as much support for a difference in the latency to attack when prey was presented by a familiar female compared to an unfamiliar male handler (LSM, estimateBS−PG = −0.685, 95% CIlow = −1.341, 95% CIup = −0.065, 1.05% inside ROPE, BF = 1.877; Fig. 3b); males took longer to attack when prey was presented by an unfamiliar male handler. However, we found no evidence that males differed in how fast they attacked prey that was presented by a familiar female compared to an unfamiliar female handler (LSM, estimateBS−LF = −0.341, 95% CIlow = −0.967, 95% CIup = 0.257, 14.95% inside ROPE, BF = 0.438; Fig. 3b) or by an unfamiliar female compared to an unfamiliar male handler (LSM, estimateLF−PG = 0.341, 95% CIlow = −0.435, 95% CIup = 1.132, 14.35% inside ROPE, BF = 0.608; Fig. 3b). Finally, we found no evidence in the simpler model for an effect of temperature on the latency to attack (GLMM, estimate = −0.132, 95% CIlow = −0.402, 95% CIup = 0.133, 3.66% inside ROPE, BF = 0.225).

Discussion

Our results show that Tokay geckos can discriminate between familiar and unfamiliar human individuals but show context-dependent behavioural responses. In the tonic immobility experiment, during which geckos experienced a novel, stressful situation, they did not exhibit behavioural differences when tested by a familiar or an unfamiliar handler. Instead, individuals behaved consistently in their duration of immobility across four trials with an inter-trial interval of one month. Contrary, in the feeding experiment, a routine situation that did not involve direct handling, geckos’ behaviour differed when tested by a familiar compared to unfamiliar handlers, but in a sex-specific way. Female geckos exhibited overall more caution with the unfamiliar handlers, while male geckos behaved more cautiously only towards an unfamiliar male handler but not an unfamiliar female handler.

Our results support our third hypothesis showing that lizards can discriminate between human handlers but take the context into account when deciding how to respond. Geckos performed similarly in the novel situation, but adjusted their behaviour to familiar and unfamiliar handlers in the routine situation. Similar to the results from a study modelling decision making based on risk49, our results show that geckos rely more strongly on past experiences (i.e. the familiarity with the handler) when the information regarding the risk level was more predictable (in the routine feeding situation). However, it is unclear why females were more sensitive to the difference in risk level compared to males. Alternatively, it is possible that when the threat level is high, as in the novel situation, geckos still discriminate between handlers, but even familiar humans may be perceived as threatening when the outcome is uncertain. A number of studies focusing on domesticated animals show that the sole presence of humans can act as a social buffer in stressful situations, modulating the animals’ stress levels (e.g. in dogs50,51,52 and goats52). Yet, even though our geckos are captive bred and have extensive experience with humans, they behaved more similarly to wild than domesticated animals.

Remarkably, this is one of the very few studies providing support that reptiles can discriminate individuals of a different species and adjust their behaviour according to context (alongside with8 in corn snakes). This finding is exciting as it enhances our understanding of reptilian behaviour and cognitive abilities related to context dependent decision-making. Geckos seem to show sensitivity to past experiences and might integrate this information to make ecologically optimal choices in a current situation by adjusting their behaviour to the threat level53. Such behaviour could be adaptive in the wild to maximise survival based on previous experiences with predators across different context. Reptiles are largely still perceived as strongly driven by innate behaviours despite a steadily growing body of evidence suggesting the opposite21,22,23. In line with these previous demonstrations of sophisticated cognitive abilities, our results clearly demonstrate our geckos ability to make decisions based on past experience modulated by risk level (predictability of the context outcomes). Additionally, our findings have implications for reptile welfare, because they suggest differential perception of individual handlers which could have implications for cognitive bias and influence affective state (negatively or positively). However, how handler identity influences internal state, and therefore, welfare needs to be tested in the future.

Importantly, our study also raise implications for data quality and research reproducibility. We show that (1) the identity of the researcher does introduce error into the data which needs to be accounted for, and (2) that the effect might vary from protocol to protocol. Our results also provide support that geckos are not just able to discriminate familiar from unfamiliar humans but show more nuanced discrimination with certain handlers introducing even more error into the data leading to increased bias complexity. Female geckos were less likely to attack prey presented by a male compared to female handler, and took longer to attack prey presented by both male and female unfamiliar handlers compared to a familiar female handler. Contrary, males’ probability to attack did not differ across handlers but they did hesitate to attack prey presented by a male compared to female handlers regardless of familiarly. From this data, we are unable to disentangle if geckos’ change in their responses were due to handler sex (female versus male), similar to what was found in mice20, or if the change in responses was specific to the individual unfamiliar handlers. To better understand the discrimination ability of these animals, future studies could manipulate experimenter roles (bad versus good). In any case, it highlights that a first step to mitigate the reproducibility crisis in experimental studies could be to consider the effect of handler identity in animal behaviour experiments, as this might impact the animals’ behaviour in complex ways9,11. Additionally, as of yet, we have no information regarding which cues lizards use to make the discrimination between human handlers. Geckos rely heavily on chemicals for social communication54,55, but they also have a well-developed visual system56. Therefore, a whole range of cues or combinations might be used. It is also possible that, the more information across different modalities is available at a given moment, the better their ability to discriminate and this should be tested in the future.

It is worth noting that we found high intra-individual consistency in the duration of immobility across time regardless of who performed the protocol. Consistent tonic immobility behaviour across trials was found in birds (Yellow-crowned bishop, Euplectes afer; Tree sparrow, Passer montanus57), amphibians (smooth newt, Lissotriton vulgaris58), and insects (yellow mealworm beetle, Tenebrio molitor59), and here we add evidence in a gecko. Moreover, we found a repeatability of 0.41 (and 0.55 after removing trials where lizards did not upright) for the duration of immobility, which is higher than average in studies on animal behaviour (Raverage = 0.37), twice as high as what is found on average in ectotherms (R = 0.22–0.27) and equal to what is commonly found in endotherms (R= 0.32–0.40)60. This is quite remarkable, as these lizards never lived in the wild (and thus never encountered a natural predator)60, were habituated to humans, and underwent repeated trials with intervals of one month. This individual repeatability can be interpreted as a personality trait61 potentially measuring boldness or antipredator behaviour57, and due to its consistency in the current experiment, might have a genetic basis rather than being based on experience62. Finally, some lizards showed laterality in turning behaviour in tonic immobility. In previous studies, we did not find laterality in turning behaviour when approached by a threat from behind, nor in prey capture behaviour when feeding from forceps (unpublished data). However, our sample size and number of repetitions were small in both studies and results should be interpreted with caution. Geckos’ behavioural lateralisation should be further investigated in the future.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate context dependent behavioural responses in Tokay geckos in which individuals behave according to a match or mismatch between handler and context familiarity. When the context was a novel situation, geckos behaved similarly when handled by familiar and unfamiliar researchers; when the context was a routine situation, geckos behaved differently when tested by familiar or unfamiliar handlers, in a sex specific way. Hence, geckos seem to be able to discriminate among heterospecifics such as different human individuals, but they act upon it depending on the context. Accounting for the effect of handler identity in experiments can thus be crucial for refining study design and mitigating potential sources of measurement error, which can have implications for data quality and contribute to the global reproducibility crisis in research. Additionally, our data are in support of our lizards’ capability to assess the context of a situation and make behavioural decisions accordingly, which provides further evidence that they are not purely driven by innate behaviours but rather are complex cognitive beings21,22,23. Overall, our study bears implications for experimental practices, while further contributing to our understanding of reptile behaviour and cognition.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Open Science Framework repository, doi: 10.17605/OSF.IO/ZESHV).

References

Yorzinski, J. L. The cognitive basis of individual recognition. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 16, 53–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.03.009 (2017).

Bernstein, I. S. & Ehardt, C. L. Agonistic aiding: kinship, rank, age, and sex influences. Am. J. Primat. 8(1), 37–52 (1985).

Tanner, C. J. & Adler, F. R. To fight or not to fight: context-dependent interspecific aggression in competing ants. Anim. Behav. 77(2), 297–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.10.016 (2009).

Baker, M. 1500 Scientists lift the lid on reproducibility. Nature 533, 452–454 (2016).

Gould, E., et al. Same data, different analysts: variation in effect sizes due to analytical decisions in ecology and evolutionary biology. EcoevoRxiv, 1–76; 10.32942/X2GG62 (2023).

Hills, A. & Webster, M. M. Sampling biases and reproducibility: experimental design decisions affect behavioural responses in hermit crabs. Anim. Behav. 194, 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2022.09.017 (2022).

Kressler, M. M., Gerlam, A., Spence-Jones, H. & Webster, M. M. Passive traps and sampling bias: social effects and personality affect trap entry by sticklebacks. Ethology 127(6), 446–452. https://doi.org/10.1111/eth.13148 (2021).

Nagabaskaran, G., Burman, O. H. P., Hoehfurtner, T. & Wilkinson, A. Environmental enrichment impacts discrimination between familiar and unfamiliar human odours in snakes (Pantherophis guttata). App Anim. Behav. Sci. 237, 105278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2021.105278 (2021).

Van Driel, K. S. & Talling, J. C. Familiarity increases consistency in animal tests. Behav. Brain Res. 159(2), 243–245; 1016/j.bbr.11.005 (2005). (2004).

Skinner, M., Brown, S., Kumpan, L. T. & Miller, N. Snake personality: differential effects of development and social experience. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 76(10), 135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-022-03227-0 (2022).

Rabdeau, J., Badenhausser, I., Moreau, J., Bretagnolle, V. & Monceau, K. To change or not to change experimenters: caveats for repeated behavioural and physiological measures in Montagu’s Harrier. J. Avian Biol. 50(8), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/jav.02160 (2019).

Davis, H. Research animals discriminating among humans. ILAR J. 43(1), 19–26 (2002).

Newport, C., Wallis, G., Reshitnyk, Y. & Siebeck, U. E. Discrimination of human faces by Archerfish (Toxotes chatareus). Sci. Rep. 6, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27523 (2016).

Miller, S. L. et al. Zebrafish (Danio rerio) distinguish between two human caretakers and their associated roles within a captive environment. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 267, 106053. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2023.106053 (2023).

Davidson, G. L., Clayton, N. S., Thornton, A. & Wild jackdaws Corvus Monedula, recognize individual humans and May respond to gaze direction with defensive behaviour. Anim. Behav. 108, 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2015.07.010 (2015).

Lee, W. Y. et al. Antarctic Skuas recognize individual humans. Anim. Cogni. 19(4), 861–865. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-016-0970-9 (2016).

Lee, W. Y., Lee, S., Choe, J. C. & Jablonski, P. G. Wild birds recognize individual humans: experiments on magpies, Pica Pica. Anim. Cogni. 14(6), 817–825. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-011-0415-4 (2011).

Levey, D. J. et al. Wild Mockingbirds distinguish among familiar humans. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36225-x (2023).

Marzluff, J. M., Walls, J., Cornell, H. N., Withey, J. C. & Craig, D. P. Lasting recognition of threatening people by wild American crows. Anim. Behav. 79(3), 699–707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.12.022 (2010).

Georgiou, P. et al. Experimenters’ sex modulates mouse behaviors and neural responses to ketamine via Corticotropin releasing factor. Nat. Neurosci. 25(9), 1191–1200. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-022-01146-x (2022).

Burghardt, G. M. Environmental enrichment and cognitive complexity in reptiles and amphibians: concepts, review, and implications for captive populations. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 147(3–4), 286–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2013.04.013 (2013).

Font, E., Burghardt, G. M., Leal, M. & Brains, Behaviour, and cognition: multiple misconceptions. In Health and Welfare of Captive Reptiles (eds Warwick, C. et al.) 211–238 (Springer International Publishing, 2023).

Szabo, B., Noble, D. W. & Whiting, M. J. Learning in non-avian reptiles 40 years on: advances and promising new directions. Biol. Rev. 96(2), 331–356. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12658 (2021).

Grossmann, W. D. & Tokeh,. Gekko gecko (Natur und Tier, 2006).

Vergera, M. O., Devillebichotc, M., Ringler, R. & Szabo, B. Sex-specific discrimination of familiar and unfamiliar mates in the Tokay gecko. Anim. Cogni. 27(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-024-01896-0 (2024).

Szabo, B. & Ringler, E. Geckos differentiate self from other using both skin and faecal chemicals: evidence towards self-recognition? Anim. Cogni. 26(3), 1011–1019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-023-01751-8 (2023).

Prestrude, A. M. & Crawford, F. T. Tonic immobility in the Lizard, Iguana iguana. Anim. Behav. 18, 391–395 (1970).

Rogers, S. M., Simpson, S. J. & Thanatosis Cur Biol. 24(21), R1031-R1033; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2014.08.051 (2014).

Humphreys, R. K. & Ruxton, G. D. A review of thanatosis (death feigning) as an anti-predator behaviour. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 72(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-017-2436-8 (2018).

Herzog, H. A. & Drummond, H. Tail autotomy inhibits tonic immobility in geckos. Copeia 1984(3), 763. https://doi.org/10.2307/1445161 (1984).

McKnight, R. R., Copperberg, G. F. & Ginter, E. J. Duration of tonic immobility in lizards (Anolis carolinensis) as a function of repeated immobilization, frequent handling, and laboratory maintenance. Psychol. Record. 28, 549–556 (1978).

Sherbrooke, W. C. & May, C. J. Body-flip and immobility behavior in Regal horned lizards: A gape-limiting defense selectively displayed toward one of two snake predators. Herpetol Rev. 39(2), 156–162 (2008).

Percie du Sert, N. et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 18, e3000410. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000410 (2020).

Loew, E. R. A third, ultraviolet-sensitive, visual pigment in the Tokay gecko (Gekko gecko). Vis. Res. 34, 1427–1431 (1994).

Szabo, B. Changes in enclosure use and basking behaviour associated with pair housing in Tokay geckos (Gekko gecko). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 106179 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2024.106179 (2024).

Friard, O. & Gamba, M. B. O. R. I. S. A free, versatile open-source eventlogging software for video/audio coding and live observations. Meth Ecol. Evol. 7, 1325–1330 (2016).

Telemeco, R. S., Baird, T. A. & Shine, R. Tail waving in a Lizard (Bassiana duperreyi) functions to deflect attacks rather than as a pursuit-deterrent signal. Anim. Behav. 82(2), 369–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2011.05.014 (2011).

Szabo, B. & Ringler, E. Fear of the new? Geckos hesitate to attack novel prey, feed near objects and enter a novel space. Anim. Cogni. 26(2), 537–549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-022-01693-7 (2023).

Peig, J. & Green, A. J. New perspectives for estimating body condition from mass/length data: the scaled mass index as an alternative method. Oikos 118(12), 1883–1891. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0706.2009.17643.x (2009).

Bürkner, P. C. Brms: an R package for bayesian multilevel models using Stan. J. Stat. Softw. 80(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v080.i01 (2017).

Bürkner, P. C. Advanced bayesian multilevel modeling with the R package Brms. R J. 10(1), 395–411. https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2018-017 (2018).

Bürkner, P. C. Bayesian item response modeling in R with Brms and Stan. J. Stat. Softw. 100(5), 1–54. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v100.i05 (2021).

Stoffel, M. A., Nakagawa, S. & Schielzeth, H. RptR: repeatability Estimation and variance decomposition by generalized linear mixed-effects models. Meth Ecol. Evol. 8, 1639–1644. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12797 (2017).

Lenth, R. V. & emmeans Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. R package version 1.7.0.; (2021). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; (2022). https://www.R-project.org/

Makowski, D., Ben-Shachar, M., Lüdecke, D. & bayestestR Describing effects and their uncertainty, existence and significance within the bayesian framework. J. Open. Source Softw. 4(40), 1541. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.01541 (2019).

Patil, I., _pairwiseComparisons & < Multiple Pairwise Comparison Tests_; (2019). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=pairwiseComparisons

Schmalz, X., Biurrun Manresa, J., Zhang, L. What is a Bayes factor? Psychol. Methods 28(3), 705–719; 10.1037/met0000421 (2023).

Luttbeg, B. & Trussell, G. C. How the informational environment shapes how prey estimate predation risk and the resulting indirect effects of predators. Am. Nat. 181(2), 182–194. https://doi.org/10.1086/668823 (2013).

Coppola, C. L., Grandin, T. & Enns, R. M. Human interaction and cortisol: can human contact reduce stress for shelter dogs? Physiol. Behav. 87(3), 537–541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.12.001 (2006).

Willen, R. M., Mutwill, A., MacDonald, L. J., Schiml, P. A. & Hennessy, M. B. Factors determining the effects of human interaction on the cortisol levels of shelter dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 186, 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2016.11.002 (2017).

Scandurra, A. et al. Human social buffer in goats and dogs. Anim. Cogni. 27(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-024-01861-x (2024).

Rosati, A. G. & Stevens, J. R. Rational decisions: the adaptive nature of Context-Dependent choice. Fac. Publications Department Psychol. 525; (2009). https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/psychfacpub/52

Martín, J. & López, P. Pheromones and reproduction in reptiles. In Hormones and Reproduction of Vertebrates (eds Norris, D. O. & Lopez, K. H.) 141–167 (Academic, 2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-374930-7.10006-8 .

Mason, R. T. & Reptilian pheromones in Biology of the Reptilia – Hormones, Brain, and Behavior (ed. Gans, C., Crews, D.) 114–228Branta Books, (1992).

Roth, L. S., Kelber, A. Nocturnal colour vision in geckos. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 271(suppl_6), S485-S487; 10.1098/rsbl.2004.0227 (2004).

Edelaar, P. et al. Tonic immobility is a measure of boldness toward predators: an application of bayesian structural equation modeling. Behav. Ecol. 23(3), 619–626. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/ars006 (2012).

Baškiera, S. & Gvoždík, L. Thermal dependence and individual variation in tonic immobility varies between sympatric amphibians. J. Therm. Biol. 97, 102896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtherbio.2021.102896 (2021).

Krams, I. et al. High repeatability of Anti-Predator responses and resting metabolic rate in a beetle. J. Insect Behav. 27(1), 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10905-013-9408-2 (2014).

Bell, A. M., Hankison, S. J. & Laskowski, K. L. The repeatability of behaviour: a meta-analysis. Anim. Behav. 77(4), 771–783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.12.022 (2009).

Réale, D., Dingemanse, N. J. Animal Personality. ELS, 1–8; 10.1002/9780470015902.a0023570 (2012).

Carli, G. & Farabollini, F. Tonic immobility as a survival, adaptive response and as a recovery mechanism. Progress Brain Res. 271(1), 305–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.pbr.2022.02.012 (2022).

ASAB Ethical Committee, ABS Animal Care Committee. Guidelines for the treatment of animals in behavioural research and teaching. Anim. Behav. 195, I-XI; (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2022.09.006

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Philippe Graber and Lea Fröhlich for their help in collecting data for the routine experiments. We also would like to thank Eva Zwygart and her team for taking care of the insects. Finally, we also thank the project CRC-TRR 212, number 316099922, “A novel synthesis on individualisation across Behaviour, Ecology and Evolution (NC3)”.

Funding

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) [grant 310030_197921, PI: ER], the University of Bern [Open Round 2022 grant to BS] and by the German Research Foundation (DFG) [project 502040958 to IDM].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IDM, BS - Conceptualization; IDM, BS - Data curation; BS - Formal analysis; IDM, ER, BS - Funding acquisition; IDM, ER, LB, BS - Investigation; IDM, BS - Methodology; BS - Project administration; ER, BS - Resources; BS - Validation; IDM, BS - Visualization; IDM, BS - Roles/Writing - original draft; IDM, ER, LB, BS - Writing - review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical statement

Our tests followed the guidelines provided by the Association for the Study of Animal Behaviour/ Animal Behaviour Society for the treatment of animals in behavioural research and Teaching63. Experiments were approved by the Suisse Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office (National No. 33232, Cantonal No. BE144/2020, BE9/2024). Captive conditions were approved by the Suisse Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office (Laboratory animal husbandry license: No. BE4/2022). All lizards were part of our permanent captive stock and were retained in our facility after the experiments.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Damas-Moreira, I., Bégué, L., Ringler, E. et al. Tokay geckos adjust their behaviour based on handler familiarity but according to context. Sci Rep 15, 11364 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95936-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95936-5