Abstract

This study assessed the severity of mental health concerns, including depression and anxiety, and identified its association with psychosocial and caregiving factors. A cross-sectional study involved 213 family caregivers of lung cancer patients was conducted between June 2023 and August 2024 at a general provincial hospital in Northern Vietnam. Mental health concerns, caregiving challenges (burden, preparedness, and readiness for surrogate decision-making) and psychosocial factors (quality of life and social support) were measured. Modified Poisson regression examined associations between these factors with mental health concerns. Approximately 37% screened positive for mental health concerns, with 29.1% and 27.2% experiencing mild-to-severe depression and anxiety, respectively. Factors positively associated with mild-to-severe depression included being female (Prevalence ratio [PR] = 1.79, 95%CI: 1.07, 3.01), higher caregiving burden (PR = 1.06, 95%CI: 1.04, 1.08) and better caregiving preparedness (PR = 1.34, 95%CI: 1.02, 1.75). Similarly, caregiving burden (PR = 1.05, 95%CI: 1.02, 1.07) was positively associated with mild-to-severe anxiety. Conversely, better quality of life was negatively associated with both mild-to-severe depression (PR = 0.97, 95%CI: 0.95, 0.99) and anxiety (PR = 0.96, 95%CI: 0.94, 0.98). Only social support from friends (PR = 0.87, 95%CI: 0.77, 0.98) was negatively associated with mild-to-severe anxiety. No association was observed between readiness for surrogate decision-making and either mild-to-severe depression or anxiety. This study underscores the significant prevalence of mental health concerns, with one in ten family caregivers meeting the threshold for mental health treatment. The findings advocate for routine mental health screening to enable early identification and intervention. Promoting well-being and bolstering social connections is a critical strategy to mitigate mental health concerns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In high-income countries (HICs), patients generally benefit from having a team of bedside care professionals to provide nursing care, bedside assistance, and physical therapy1. In contrast, in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), underdeveloped healthcare and social welfare systems usually place family members into the primary caregiver role for patients2,3. This disparity is particularly concerning for lung cancer, the second highest prevalent cancer worldwide, which disproportionately burdens LMICs (where 60% of new diagnoses occur), and is the most prevalent cause of cancer-related fatalities4. Vietnam, a lower-middle income country, exemplifies this challenge: lung cancer is the third highest diagnosed cancer in 2022, with over 24,000 cases and claiming over 22,000 lives, ranking the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality5. Furthermore, lung cancer caregivers carry a heavier toll since lung cancer patients also experience more pronounced symptoms than patients with other cancers6,7 and often transition to palliative care8, which intensifies the reliance on family caregivers for assistance.

LMIC caregivers, including those from Vietnam, often manage a multifaceted role9,10,11, taking on nurse-oriented tasks (e.g., medication administration), on top of other typical family supports, including personal care, emotional support, financial assistance, and even medical decision-making. For example, family members in China typically handle 70–80% of caregiving duties10. In Uganda, family caregivers take on a wide range of tasks, such as providing emotional support (79.8%), feeding assistance (68.5%), transportation (62.5%), meal preparation (55%), and medication administration (46.4%)11. However, they lack resources readily available compared to those in HICs. Particularly, caregivers have limited healthcare access, coupled with limited health literacy, a lack of essential training for disease management and daily care, and minimal support from trained health professionals who prioritized patients themselves9,11,12,13,14, which forces them to navigate complex medical situations alone9. This training gap, particularly prevalent in LMICs11 and for those caring for lung cancer patients13, leaves family uncertain about how to provide care, how to seek professional health, and how to deliver optimal cancer care15. This significantly increases their caregiving burden and can lead to severe physical and psychological distress12. Recognizing the vital but unrecognized and unpaid role played by these family caregivers and understanding the complex relationship between caregiving burden and their mental well-being in this specific context is essential.

While studies in middle- and high-income countries reported concerning rates of depression in caregivers of patients with any cancer types at 42.1%, research specific to caregivers in low-income settings such as Vietnam16 and of lung cancer patients is lacking3. Additionally, there is limited understanding on contributing caregiving factors to these concerns16,17,18. In Vietnam, existing studies on mental health symptomatology primarily focused on cancer patients19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26. Only one study explored caregivers of all cancer patients, highlighting high psychological distress16, but a more nuanced understanding, especially for caregivers of hospitalized lung cancer patients, is necessary8. Therefore, further investigation is needed to understand mental health concerns among family caregivers of these hospitalized patients, particularly focusing on how caregiving factors influence these concerns.

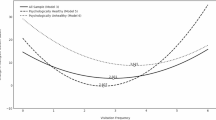

This study was grounded by the Stress Process Model27 (Fig. 1), which, at its core, acknowledges that caregiving is a stressful experience that can directly impact mental health. According to this model, mental health is influenced by the combined and interconnected effect of contextual elements (e.g., length of stay, preparedness for caregiving, and quality of life), primary patient-related stressors (e.g., caregiving burden), secondary situational stressors (e.g., readiness for medical decision-making), and available resources (e.g., social support)28. Thus, this study evaluated mental health concerns among family caregivers of hospitalized lung cancer patients, including prevalence and its associations with psychosocial factors (e.g., quality of life and social support) and caregiving factors (e.g., burden and preparedness for caregiving, readiness for surrogate decision-making). We hypothesized that family caregivers with greater preparedness, better quality of life, lower caregiving burden, stronger social support, and higher readiness for decision-making report fewer mental health concerns. By comprehensively examining these factors, we can identify the most robust contributors to mental health symptomatology, laying the groundwork for devising tailored support programs that cater to cancer caregivers’ specific needs in LMICs.

Methods

Study design

From June 2023 to August 2024, a cross-sectional study was conducted at the Oncological Center situated within a provincial general hospital in a predominantly rural area, in the Red River Delta in Northern Vietnam. Known as the industrial center of Vietnam, the Red River Delta is among the wealthiest and most developed areas in the nation. During the first nine months of 2022, the study center delivered over 6,296 treatment visits for cancer patients, with lung cancer treatment comprising the largest portion at 16.1%. Additionally, more than two-thirds of lung cancer patients received palliative care at the center during this period29. During the study period, all caregivers in this specific setting are family caregiver members, a reflection of the region’s collectivist culture and strong emphasis on filial piety. The combination of these unique characteristics allowed us to examine the physical and mental health among informal family caregivers of hospitalized lung cancer patients in an LMIC setting.

Sample size and participant eligibility

Based on a reported prevalence of caregiver psychological distress of 16.5%16, sample size was determined using the formula: n=\(\:\frac{{Z}^{2}*\:p(1-p)}{{d}^{2}}\), where p=0.165 represents the prevalence; Z=1.96 denotes the critical value for a 95% confidence interval; and d=0.05 indicates the designed margin of error. Finally, we recruited 213 caregivers who were (1) adults (≥ 18 years old); (2) a spouse/partner, parent, children, sibling, and other familial relation (niece/nephew, aunt/uncle); (3) provided unpaid caring for hospitalized lung cancer patients; (4) fluent in Vietnamese; and (5) willing to voluntarily participate in a 20–30-minute survey. Individuals with self-reported pre-existing mental health conditions (e.g., depression, anxiety) were excluded. A multi-step recruitment approach was applied, with healthcare providers introducing the study aims and procedures, followed by consecutive sampling to select family caregivers. As a result, family caregivers of hospitalized lung cancer patients from all oncological stages were included. Data collectors approached potential participants during caregiving breaks or at a time the caregiver preferred. In-person surveys were then conducted.

Measurements

Mental health concerns

We assessed caregivers’ mental health symptomatology using two standardized instruments: the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; 9 items)30 and General Anxiety Disorders (GAD-7; 7 items)31. Both measures assessed symptoms experienced over the previous two weeks. A 4-point scale, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day), was used for each item. Higher PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores, which ranged from 0 to 27 and 0 to 21, respectively, indicated greater severity of depression and anxiety. The PHQ-9 was grouped into five categories: minimal (0–4), mild (5–9), moderate (10–14), moderately severe (15–19), and severe (20–27), while GAD-7 was classified into the following categories: minimal (0–4), mild (5–9), moderate (10–14), and severe (15–21). Scores of ≥ 5 on either the PHQ-9 or GAD-7 scale indicated mental health concerns, signaling risks for depression or anxiety, respectively. Good internal consistency was shown in this cohort by Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.85 and 0.89 for PHQ-9 and GAD-7, respectively.

Caregiving factors encompassed three dimensions:

-

(1)

Caregiving burden was measured by using the short version of Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI; 12 items), a validated instrument in advanced illnesses such as cancer32. Caregivers rated each item on a 5-point scale of 0 to 4 to show their feelings while caring for family members, with 0 being “never” and 4 being “nearly always,” yielding a total score ranging from 0 to 48. In this study, the ZBI demonstrated good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84.

-

(2)

Caregiving preparedness was evaluated using the Preparedness for Caregiving Scale (PCS; 8 items)33. This scale gauged caregivers’ perceptions of their preparedness to fulfill caregiving duties, such as “How well prepared do you think you are to take care of your family member’s physical needs?” Response options ranged from 0 (not at all prepared) to 4 (very well prepared). Greater preparedness was indicated by higher overall scores. With Cronbach’s alpha of 0.94, the PCS showed excellent internal consistency.

-

(3)

Readiness for future surrogate decision-making was assessed using the Family Decision-Making Self-Efficacy Scale for conscious patient (FDMSES; 13 items)34. This scale measured the confidence levels of family members in decision-making for a terminally ill loved one. A score of 1 (cannot do at all) to 5 (certain I can do) was assigned to each item. Scores ranged from 13 to 75, where higher scores indicated higher readiness for future surrogate decision-making. The Cronbach’s alpha for this measure was 0.93, indicating excellent internal consistency.

Psychosocial factors included two dimensions:

-

(1)

Quality of life: We administered the Quality-of-Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire – Short Form (Q-LES-SF; 15 items) to measure past-week quality of life35. Participants ranked their contentment with different life aspects using a 5-point scale ranging from very poor (1) to very good (5). Raw scores varied from 14 to 70 and then were transformed into the maximum total score (0-100), with higher scores suggesting a better quality of life. The Cronbach’s alpha in this study was 0.90, suggesting excellent internal consistency.

-

(2)

Social support: We used Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; 12 items) to measure social support from family (e.g., “I can talk about my problems with my family”), friends (e.g., “I have friends with whom I can share my joys and sorrows”), and significant others (e.g., “There is a special person in my life who cares about my feelings”)36. A 7-point scale was used for each item, with 1 denoting “very strongly disagree” and 7 denoting “very strongly agree”. Total score for each domain was determined by averaging its respective items. The measure had excellent internal consistency in this study, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91.

Caregivers’ characteristics included age (in years), sex (male vs. female), ethnicity (Kinh vs. other), current employment (retired, unemployed, and employed), educational level (less than high school vs. high school and higher), past-year monthly income (≤ 5, > 5–7, > 7–10, and > 10 million Vietnam Dong), and relationship to patients (spouse/partner, parent, children, sibling, and other). Additionally, we inquired about the duration of caregiving during this treatment (in days), frequency of caregiving (in hours per day), and the number of caregivers involved.

Hospitalized lung cancer patients’ characteristics: We gathered data on age in years, sex (male vs. female), metastatic stage (I, II, III, and IV), treatment methods (Only medication, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, combined), duration of treatment (in days), and numbers of treatment times at the study hospital.

Statistical analysis

For mental health concerns, depression and anxiety symptomatology severity, frequencies and percentages were reported. A combination of t-tests, Fisher’s exact tests, and chi-squared statistics were utilized in bivariate analyses to examine the differences and associations of demographics, caregiving factors (caregiving burden, preparedness for caregiving, and readiness for surrogate decision-making), and psychosocial factors (e.g., social support and quality of life) with mental health concerns. Multivariable Poisson regression with robust variance (Modified Poisson) analyses using backward stepwise selection was employed due to elevated occurrence of mental health concerns, as it approximates risk ratios more accurately than binary logistic regression37. This approach estimated adjusted prevalence rates (PRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to assess the association between predictors and mental health concerns. The final model was assessed based on (1) Deviance and Pearson residuals, which showed random scatter indicating a good fit, and (2) collinearity diagnostics, with variance inflation factors (VIFs) all below 10, suggesting no issues with multicollinearity.

To provide a robust assessment of the findings, sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate factors associated with moderate-to-severe depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 10), moderate-to-severe anxiety (GAD-7 ≥ 10), and the need for mental health services (either PHQ-9 ≥ 10 or GAD-7 ≥ 10). We also conducted subgroup analysis to examine factors associated with mild-to-severe depression and anxiety by sex (male, female), education level (less than high school, high school or higher), caregiving duration (≤ 8 h, > 8 h per day), and patient’s cancer stages (early, advanced).

Data management and analyses were conducted using STATA software version 18 (STATA Corp., College station, TX).

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at Hanoi University of Public Health, Vietnam (211/2023/YTCC-HD3) and City University of New York (2023-0754-PHHP), USA. All participating family caregivers voluntarily provided a written informed consent form.

Results

Family caregivers’ demographic characteristics and mental health concerns

The mean age of caregivers was 50.4 years (SD = 13.5; Table 1), with the majority being between 40 and 59 years (47.9%) and 60–74 years (32.4%). More than two-thirds (68.1%) were female, and all participants identified as Kinh ethnicity. Approximately 62.4% had an education level below high school, and nearly half (48.8%) were farmers. Among those employed, most (57.8%) reported a monthly income of less than 5 million Vietnam Dong (~ USD $197, 1 USD = 25,400 Vietnam Dong).

Caregivers were predominantly immediate family members, including spouse (39.9%) and children (43.7%). Up to 45.1% of lung cancer patients had two family caregivers. The median number of days spent caring for lung cancer patients during the current treatment was 4 days (IQR: 2–6 days), with a median of 12.8 h per day (IQR: 8-16.7). The median total time spent caring for the patient during the current treatment was 45 h (IQR: 27–76).

Bivariate analyses revealed that demographic factors such as sex and monthly income were associated with both mild-to-severe depression and anxiety. In contrast, educational level, and the number of hours taking care of patients in the current treatment were solely associated with anxiety.

Prevalence of mental health concerns among family caregivers of lung cancer patients

Mental health concerns were reported by over one third of caregivers (36.6%; Fig. 2). Depression and anxiety were identified as risks for 29.1% and 27.2%, respectively. Overall, 9.9% of participants had moderate-to-severe levels of either depression or anxiety.

In terms of symptom severity for depression, 22.5% of participants exhibited mild symptoms, while 2.4% showed moderate symptoms. The percentages for moderate-severe and severe symptoms for depression were 3.3% and 0.9%, respectively. For anxiety, 18.3% reported experiencing mild symptoms and 5.2% had moderate symptoms. About 3.7% had severe symptoms.

Lung cancer patients’ clinical characteristics and mental health concerns

Patients had a mean age of 67.1 years (SD = 9.5), with most in the senior group (60–72 years, 81.2%), followed by middle group (40–59 years, 18.3%; Table 2). Over three-quarters of patients (77.5%) were male. More than half presented with advanced stages (Stage III: 19.7%, and stage IV: 37.1%). Approximately half of the patients were receiving medication. About 26.3% of patients were being treated at the study hospital for the first time. The median length of stay at this hospital was 7 days (IQR: 3–19 days).

Bivariate analyses indicated that only the length of hospital stay was associated with both depression and anxiety.

Caregiving factors and mental health concerns

The average caregiving burden score, as measured by the Zarit caregiver burden scale32, was 12.4 out of 48 (SD = 7.3; Table 3). Family caregivers at risk for depression (mean = 17.6 ± 9.2) and anxiety (mean = 17.3 ± 8.4) reported significantly higher burden than those not at risk (means = 10.3 ± 5.0 and 10.6 ± 5.8, respectively, p < 0.001).

Caregiving preparedness averaged 1.9 out of 4 (SD = 0.8), with those at risk for anxiety (mean = 1.7 ± 0.9) reporting lower preparedness than those without risk (mean = 2.0 ± 0.8, p < 0.01).

Readiness for surrogate decision-making averaged 50.5 out of 65 (SD = 9.2). There was no significant relationship between readiness and mental health concerns.

The standardized score for quality of life was 50.3 out of 100 (SD = 13.5). Caregivers at risk for depression (mean = 43.1 ± 12.7) and anxiety (mean = 41.3 ± 12.1) reported significantly lower quality of life compared to those not at risk (means = 53.2 ± 12.7 and 53.7 ± 12.4, respectively, p < 0.001).

Overall, perceived social support averaged 5.8 out of 7 (SD = 0.9). The mean scores for social support were 6.1 (SD=0.8) from family, 5.2 (SD=1.3) from friends, and 5.9 (SD=1.1) from their significant other. Additionally, social support from friends was significantly associated with both depression and anxiety (p < 0.05), while social support from family was solely linked to depression.

Association of demographics, psychosocial and caregiving factors with mental health concerns

The multivariable models, which included age and education, showed minimal changes in prevalence ratios. Therefore, these variables were excluded to enhance model parsimony.

In the adjusted model (Fig. 3), female caregivers had a 79% higher probability of being at risk for mild-to-severe depression symptoms (PHQ-9 ≥ 5) compared to male counterparts (PR = 1.79, 95%CI: 1.07, 3.01). Higher caregiving burden was associated with higher risk of mild-to-severe depression (PR = 1.06, 95%CI: 1.04, 1.08). Similarly, higher preparedness for caregiving reported higher probability of mild-to-severe depression (PR = 1.34, 95%CI: 1.02, 1.75). In contrast, caregivers who reported better quality of life had lower probability of experiencing mild-to-severe depression (PR = 0.97, 95%CI: 0.95, 0.99). No significant associations were observed between readiness for surrogate decision-making and perceived social support with mild-to-severe depression. In the sensitivity analysis for factors associated with moderate-to-severe depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 10), we found similar findings as those for mild-to-severe depression, with the exception that being female was not significantly associated with moderate-to-severe depression (Supplemental Table 1).

Regarding anxiety (Fig. 4), higher caregiving burden (PR = 1.05, 95%CI: 1.02, 1.07) was associated with higher likelihood of being at risk for mild-to-severe anxiety (GAD-7 ≥ 5). Conversely, both better quality of life (PR = 0.96, 95%CI: 0.94, 0.98) and greater social support from friends (PR = 0.87, 95%CI: 0.77, 0.98) were associated with lower likelihood of mild-to-severe anxiety symptoms. Caregiving preparedness, readiness for surrogate decision-making, and family social support were not significantly associated with anxiety risks. In the sensitivity analysis for factors associated with moderate-to-severe anxiety (GAD-7 ≥ 10), we found similar findings as those for mild-to-severe anxiety, with the exception that social support from friends was no longer significant, while caregiving prepared (PR = 1.65, 1.02, 2.67) was significantly associated with moderate-to-severe anxiety (Supplemental Table 1).

Subgroup analysis of factors associated with mental health concerns

Subgroup analyses (Supplemental Table 2), including male caregivers, caregivers with a caregiving duration of > 8 h per day, and caregivers of advanced cancer patients, mirrored our findings using the whole sample regarding factors associated with mild-to-severe depression. Specifically, a higher caregiving burden and better preparedness for caregiving were linked to a higher probability of mild-to-severe depression, while a better quality of life was associated with a lower probability. Among the subgroup analysis of female caregivers, caregivers with less than a high school education and those with a high school education or higher, the findings were also consistent: higher caregiving burden and better preparedness for caregiving were associated with a higher probability of mild-to-severe depression. Only a better quality of life was associated with a lower probability among caregivers of non-advanced cancer patients.

Similarly, subgroup analyses, including female caregivers, caregivers with less than a high school education or those with a high school education or higher, caregivers with a caregiving duration of ≤ 8 h and > 8 h per day, and caregivers of advanced cancer patients, also reflected our overall findings regarding factors associated with mild-to-severe anxiety. Particularly, higher caregiving burden was linked to a higher probability of mild-to-severe anxiety, while a better quality of life was associated with a lower probability. Surprisingly, no significant associations were observed between psychosocial and caregiving factors and mild-to-severe anxiety among male caregivers.

Discussion

Our study identified high levels of mental health concerns, especially mild-to-severe depression and anxiety symptoms among family caregivers for lung cancer patients in Vietnam. Notably, approximately one in ten caregivers reported moderate-to-severe levels of depression or anxiety, indicating a potential need for mental health services. Factors associated with lower risk of mental health concerns included stronger psychosocial conditions (e.g., higher quality of life and greater social support). Conversely, more challenging caregiving characteristics, such as heavier caregiving burden and higher preparedness were linked to a higher risk. Interestingly, readiness for future surrogate decision-making did not show a statistically significant association with mental health concerns. We also conducted an additional analysis to identify factors associated with the need for mental health services, aiming to prioritize those most in need of intervention. These findings mirrored those associated with mental health concerns (see Supplemental Table 1).

A high prevalence of mental health concerns was observed among family caregivers, with 36.6% reporting mild-to-severe symptoms of depression or anxiety. This is more than double the percentage observed among caregivers for a broader range of cancers in Vietnam (16.5%)16, emphasizing the greater challenges faced by lung cancer caregivers6,7, with about two-thirds of our study participants receiving palliative care. Our findings align with a previous study in China showing that 45.4% of caregivers for advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients reported slight to extreme anxiety or depression symptoms38. We also observed substantial prevalences of mild-to-severe depression (29.2%) and mild-to-severe anxiety (27.4%), which are notably higher than those reported in another Chinese study (at 19.2%)12. However, our findings are comparable to a study of advanced lung cancer caregivers, which exhibited depression and anxiety prevalence of 32.6% and 25.5%, respectively39. These findings suggest that lung cancer caregivers may need more attention with mental health screening and mental health services to help ameliorate the impact of caregiving on their well-being.

Of particular concern is the fact that approximately 10% of caregivers in our study exhibited moderate-to-severe symptoms that meet the threshold for mental health services, with 6.6% needing support for depression and 8.9% for anxiety. Our study findings are higher than those found in a similar study among lung cancer caregivers in China, which reported 5.5% of participants who were diagnosed with depression and required treatment12. This discrepancy may be attributed to differing definitions of the need for mental health services as well as the ongoing impacts of COVID-19, as the previous study population was evaluated prior to the pandemic. This data again underscores the need for more mental health support services integrated into lung cancer care system. Routine mental health assessments during hospital visits, caregiver support groups, and readily accessible counseling services are essential to reduce the mental health burden on caregivers and improve their overall well-being.

Among all demographic characteristics, only being female was included in the multivariable model, which revealed a positive association with depression. Earlier investigations support this outcome3,40,41. Particularly, a systematic review reported that female caregivers were significantly more likely to experience depression compared to male caregivers (57.6% vs. 34.4%, respectively)3. A prior study indicated that genetic, biological and environmental factors contribute to this disparity42. In our study, most lung cancer patients were male (77.4%), and within Vietnamese culture, women or wives are typically responsible for the care of their ill family members43. This caregiving role is expected regardless of the patient’s sex, with women often serving as the primary providers at the bedside during illness43. This responsibility likely increases their risk for depression. Using the Stress-Appraisal Model, Swinkels et al. suggested the interaction between caregiver sex and caregiving burden44. However, the inclusion of the interaction term in our final model did not yield significant results. These findings highlight the need for further research into specific stressors that may be unique to female caregivers, which can help guide specific interventions for this population.

Lung cancer caregivers experiencing better quality of life reported lower mental health concerns in our study. Multiple studies demonstrated the negative association between mental health concerns and quality of life40,45,46. When caregivers have a higher quality of life—meaning they experience satisfaction, fulfillment, and overall well-being—it acts as a buffer against these mental health challenges. A prior study also showed that a decade-long improvement in wellbeing reduced the risk of mental illness, whereas declines in wellbeing increased that risk47. Additionally, we found that caregivers with greater social support from friends reported fewer anxiety symptoms, likely due to their ability to share experiences related to a family member’s cancer diagnosis, understand the treatment process, and access cancer resources48. Strong social connections are crucial for lung cancer caregivers, as such support can significantly reduce caregiving burden and enhance coping abilities, ultimately leading to a higher quality of life and lower mental health concerns48. Conversely, caregivers lacking adequate social support often experience heightened levels of anxiety, depression, and distress49. Hence, improving caregivers’ quality of life and strengthening social support networks should be prioritized in public health strategies in Vietnam.

It is interesting that in this study, greater caregiving preparedness was associated with a higher likelihood of reporting mild-to-severe depression. Our subgroup analysis revealed similar findings across various groups, including male caregivers, caregivers with a caregiving duration of > 8 h per day, and caregivers of advanced lung cancer patients. This finding contradicts existing literature50, which suggests that when caregivers feel adequately equipped to handle their responsibilities, it generally leads to lower stress, healthier coping strategies, reduced burden, and more positive health-related behaviors. One possible explanation is that greater caregiving preparedness may increase caregivers’ awareness of caregiving challenges and demands51, along with perceived competency (e.g., knowledge, skills, and ability to perform tasks)52. This awareness can make caregivers more attuned to the complexities and emotional toll of the role, which could contribute to heightened stress and anxiety. In many Asian cultures, those who are well prepared are often chosen for caregiving roles. There is also a cultural norm that “it is better to care for someone than being taken care of,” which drives family caregivers to their best efforts53. This dynamic could explain why even well-prepared caregivers reported higher mental health concerns, highlighting the need for further qualitative research to explore this phenomenon.

Additionally, we found that caregivers with higher caregiving burden were more likely to report mental health concerns. When caregivers face increased demands for physical care, emotional support, and appointment scheduling—it can take a toll on their mental health54. Once these demands exceed their available resources, caregivers feel overwhelmed and report elevated stress levels55, which negatively affect their mental health. However, as our study is cross-sectional, we cannot determine if caregiving burden causes mental health concerns, or vice versa. Longitudinal studies are needed to establish causality and track changes over time. Despite this limitation, our findings emphasize the need for interventions to reduce caregiver burden and improve mental health. Hence, the expansion of family assistance programs—such as in-home nursing, home care services, and respite care —for cancer patients are essential, especially since most existing programs in Vietnam primarily focus on the elderly56. Previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of these programs for both patients and caregivers50,57. By focusing interventions on reducing caregiving burdens through family assistance programs and mental health services, we can enhance caregiver well-being and in turn, improve the quality of care they provide.

We found no statistical association between readiness for future surrogate decision-making and mental health concerns. In Western contexts, there is a strong emphasis on patient-centered care, and research has demonstrated that effective and transparent communication between health professionals and patients is crucial for ensuring high-quality care delivery58. However, in Vietnam, healthcare decisions, including diagnoses and treatments, are predominantly determined by the recommendations of healthcare providers, even when they involve costly procedures or services at all levels of care59. Therefore, the lack of association between readiness for surrogate decision-making and mental health concerns suggests that enhancing family involvement in decision-making might not directly address caregivers’ mental health issues. Given caregiver’s critical role in medical decision making and care for cancer patients in Vietnam9, it is still beneficial to engage families in these processes to help them navigate the healthcare system more effectively. Although a change from paternal decision making to patient-centered care requires a cultural shift in the way medicine is practiced in Vietnam, this approach could further mitigate caregiver stress and improve overall mental health outcomes.

Previous studies have identified significant associations between patients’ characteristics (e.g., gender, treatment method, metastatic stage)3,41, caregivers’ characteristics (e.g., age, education, and relationship with patients)18,40,41, and caregiving characteristics (e.g., during of caregiving)40 with mental health concerns. Such associations among these covariates were not found in the adjusted model in our study, possibly due to reliance on self-reported treatment information from the caregivers. Further research, including use of the medical records, is needed to assess the impact of these variables on mental health concerns among family caregivers of lung cancer patients in LMICs.

Our findings are highly relevant to other LMICs with similar healthcare constraints and collectivist culture, where family caregivers often face significant mental health challenges due to a lack of formalized support systems60. Much like Vietnam, other LMICs (e.g., Cambodia) also experienced limited access to mental health services and rely heavily on family caregivers for cancer care, especially in rural areas61. The high caregiving burden, coupled with limited resources, can significantly impact caregivers’ mental well-being, leaving them vulnerable to anxiety and depression. Thus, integrating mental health support services for caregivers into cancer care systems is crucial in LMICs.

Study limitations

This study is subject to certain limitations. First, cross-sectional design is a primary limitation, as it precludes the establishment of causality between psychosocial and caregiving factors and mental health outcomes. Future research employing longitudinal designs is crucial to determine the temporal course of caregiving-related mental health, including its persistence and potential for change. Second, data collection was restricted to a single provincial hospital in a predominantly rural area and focused on family caregivers, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other urban oncological settings and other types of caregivers (e.g., formal/paid caregivers) in Vietnam. Additionally, approximately 4% of caregivers (about 10 participants) declined to participate due to patients being discharged at the time of the survey. Despite these limitations, the results provide valuable exploratory insights into caregiving experiences and their association with mental health concerns in this specific setting. Third, while standardized scales (e.g., caregiving burden, preparedness for caregiving, and family decision-making self-efficacy) were utilized for the first time in Vietnam and demonstrated high internal consistency, further factor analyses are needed to confirm their validity. Furthermore, self-reported measures used to assess mental health, caregiving burden and preparedness are subject to social desirability bias or distress levels. While data collectors with medical background and research experience were instructed to ensure participant comfort, future studies should consider objective measures and clinical observations to improve data validity. Finally, previous studies have shown the relationship between chronic conditions, physical health issues, and other social determinants of health62,63 on mental health among caregivers of cancer patients. However, we did not collect these factors, which may limit our understanding of their combined impact on caregiver mental health. Accounting for these factors would enhance the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the findings.

Clinical implications

High prevalence of mental health concerns in this study highlights the urgent need for mental health support for family caregivers of lung cancer patients, including routine mental health screenings, accessible counseling, and caregiver support groups integrated into the lung cancer care system. These measures will ensure that mental health support becomes a fundamental component of cancer care. Additionally, caregivers with higher caregiving burdens reported more mental health concerns, suggesting that programs such as in-home nursing, home care services, and respite care can ameliorate the caregiving burden, which, in turn, improves mental health outcomes for family caregivers. Hospital policies should be modified to better support caregivers by integrating these support systems into the cancer care framework, offering caregiver training programs, creating supportive infrastructure, and advocating financial assistance. Recognizing caregivers as integral parts of the cancer care team will enhance their mental health and overall well-being.

Conclusion

Our study found high levels of depression and anxiety symptoms among lung cancer caregivers in Vietnam, with about 10% of caregivers meeting the threshold for mental health services. This highlights the urgent need for integrating comprehensive mental health support into lung cancer care system. It is particularly crucial to conduct routine mental health assessments during hospital visits, create caregiver support networks, and offer accessible counseling services to alleviate caregivers’ mental health challenges. Caregivers with better psychosocial conditions, such as improved quality of life and stronger social support, faced a lower risk of mental health issues, while those experiencing a greater caregiving burden and higher preparedness faced more challenges. To improve caregiver well-being and care quality, public health initiatives should prioritize reducing caregiving burdens through addressing disparities in health care resources, like family assistance programs and mental health services, and build programs to provide these services to lung cancer caregivers with high risk of mental health concerns in Vietnam.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available, please send request to the corresponding author (Email: vutoanthinhph@gmail.com).

References

Challinor, J. M. et al. Nursing’s potential to address the growing cancer burden in low- and middle-income countries. J. Glob Oncol.2 (3), 154–163 (2016).

Smith, L. et al. Anxiety symptoms among informal caregivers in 47 low- and middle-income countries: A cross-sectional analysis of community-based surveys. J. Affect. Disord. 298 (Pt A), 532–539 (2022).

Bedaso, A., Dejenu, G. & Duko, B. Depression among caregivers of cancer patients: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychooncology31 (11), 1809–1820 (2022).

Surapaneni, M. & Uprety, D. Lung cancer management in low and middle-income countries - current challenges and potential solutions. Int. J. Cancer Care Deliv.3(1) (2023).

J, F. et al. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/populations/704-viet-nam-fact-sheet.pdf (2024).

Lehto, R. H. Symptom burden in lung cancer: management updates. Lung Cancer Manag. 5 (2), 61–78 (2016).

Zhang, Y. et al. Relationships among perceived social support, family resilience, and caregiver burden in lung cancer families: A mediating model. Semin Oncol. Nurs.39 (3), 151356 (2023).

Gotfrit, J. et al. Inpatients versus outpatients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: characteristics and outcomes. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun.19, 100130 (2019).

Ho, H. T. et al. Understanding context: A qualitative analysis of the roles of family caregivers of people living with cancer in Vietnam and the implications for service development in low-income settings. Psychooncology30 (10), 1782–1788 (2021).

Given, B. A., Given, C. W. & Sherwood, P. The challenge of quality cancer care for family caregivers. Semin. Oncol. Nurs.28 (4), 205–212 (2012).

Muliira, J. K., Kizza, I. B. & Nakitende, G. Roles of family caregivers and perceived burden when caring for hospitalized adult cancer patients: perspective from a low-income country. Cancer Nurs.42 (3), 208–217 (2019).

Li, C. et al. Correlation between depression and intimacy in lung cancer patients and their family caregivers. BMC Palliat. Care. 21 (1), 99 (2022).

Mollica, M. A. et al. The role of medical/nursing skills training in caregiver confidence and burden: A CanCORS study. Cancer123 (22), 4481–4487 (2017).

Hu, X. et al. Caregiver burden among Chinese family caregivers of patients with lung cancer: A cross-sectional survey. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs.37, 74–80 (2018).

Given, B. A., Given, C. W. & Sherwood, P. R. Family and caregiver needs over the course of the cancer trajectory. J. Support Oncol.10 (2), 57–64 (2012).

Long, N. X. et al. Self-reported psychological distress among caregivers of patients with cancer: findings from a health facility-based study in Vietnam 2019. Health Psychol. Open.7 (2), 2055102920975272 (2020).

Karimi Moghaddam, Z. et al. Caregiving burden, depression, and anxiety among family caregivers of patients with cancer: an investigation of patient and caregiver factors. Front. Psychol. 14 (2023).

Yuliani, A. et al. Incidence of anxiety and depression and its related factors in family caregivers of cancer patients. eJournal Kedokteran Indonesia. 11 (3), 232–239 (2023).

Vu, T. T. et al. Mental health, functional impairment, and barriers to mental health access among cancer patients in Vietnam. Psycho-Oncology32 (5), 701–711 (2023).

Q., T. et al. Anxiety and depression in palliative care cancer patients in Vietnam: baseline data from a randomized controlled trial of multidisciplinary palliative care versus standard care. J. Health Res.38 (2), 106–115 (2024).

DT, M. & NT, Q. The characteristics of depression with the PHQ-9 in Gastrointestinal cancer patients at K hospital. Vietnam Med. J.502 (1), 269–272 (2021).

DA, T., VN, T. & D. VN, and Clinical features of depression in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Vietnam Med. J.507 (2), 266–269 (2021).

NLD, M. et al. Depression, quality of life and associated factors among newly admitted patients at the Hanoi oncology hospital in 2019. Vietnam J. Med. Res.125 (1), 136–143 (2020).

TTT, H. et al. Situation of anxiety among breast cancer patients at Hanoi medical university hosputal. Vietnam Med. J.515 (2), 276–279 (2022).

TL, D. & TMP, H. Distress and its correlation with potential factors among patients with cancer in Vietnam. J. Social Action Couns. Psychol.15 (1), 70–80 (2023).

Truong, D. V. et al. Anxiety among inpatients with cancer: findings from a hospital-based cross-sectional study in Vietnam. Cancer Control. 26 (1), 1073274819864641 (2019).

Pearlin, L. I. et al. Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist30 (5), 583–594 (1990).

Meyer, K. N. et al. Conceptualizing how caregiving relationships connect to quality of family caregiving within the stress process model. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work. 65 (6), 635–648 (2022).

Center, O. Patient Volume for the First Nine Months in 2022 (Vietnam, 2022).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med.16 (9), 606–613 (2001).

Spitzer, R. L. et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med.166 (10), 1092–1097 (2006).

Bédard, M. et al. The Zarit burden interview: A new short version and screening version. Gerontologist41 (5), 652–657 (2001).

Archbold, P. G. et al. Mutuality and preparedness as predictors of caregiver role strain. Res. Nurs. Health. 13 (6), 375–384 (1990).

Nolan, M. T. et al. Development and validation of the family Decision-Making Self-Efficacy scale. Palliat. Support Care. 7 (3), 315–321 (2009).

Endicott, J. et al. Quality of life enjoyment and satisfaction questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacol. Bull.29 (2), 321–326 (1993).

Zimet, G. D. et al. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J. Pers. Assess.52 (1), 30–41 (1988).

Mwebesa, E. et al. Application of a modified Poisson model in identifying factors associated with prevalence of pregnancy termination among women aged 15–49 years in Uganda. Afr. Health Sci.22 (3), 100–107 (2022).

Yang, Y. et al. Does caring for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer affect health-related quality of life of caregivers? A multicenter, cross-sectional study. BMC Public. Health. 24 (1), 224 (2024).

He, Y. et al. Sleep quality, anxiety and depression in advanced lung cancer: patients and caregivers. BMJ Support Palliat. Care. 12 (e2), e194–e200 (2022).

Geng, H. M. et al. Prevalence and determinants of depression in caregivers of cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med. (Baltim).97 (39), e11863 (2018).

Govina, O. et al. Factors associated with anxiety and depression among family caregivers of patients undergoing palliative radiotherapy. Asia Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs.6 (3), 283–291 (2019).

Sloan, D. M. & Sandt, A. R. Gender differences in depression. Women’s Health. 2 (3), 425–434 (2006).

Galanti, G. A. Vietnamese family relationships: a lesson in cross-cultural care. West. J. Med.172 (6), 415–416 (2000).

Swinkels, J. et al. Explaining the gender gap in the caregiving burden of partner caregivers. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci.74 (2), 309–317 (2019).

Rostami, M. et al. Quality of life among family caregivers of cancer patients: an investigation of SF-36 domains. BMC Psychol.11 (1), 445 (2023).

Kim, Y. The impact of depression on quality of life in caregivers of cancer patients: A moderated mediation model of spousal relationship and caring burden. Curr. Oncol.29, 8093–8102. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29110639 (2022).

Burns, R. A. et al. The protective effects of wellbeing and flourishing on long-term mental health risk. SSM - Mental Health. 2, 100052 (2022).

Yuen, E. Y. N., Hale, M. & Wilson, C. The role of social support among caregivers of people with cancer from Chinese and Arabic communities: a qualitative study. Support. Care Cancer. 32 (5), 310 (2024).

Bouchard, E. G. et al. Understanding social network support, composition, and structure among cancer caregivers. Psychooncology32 (3), 408–417 (2023).

SC, R. et al. Chap. 14 supporting family caregivers in providing care, in Patient Safety and Quality: an evidence-based Handbook for Nurses. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US): Rockville (MD). (2008).

Uhm, K. E. et al. Influence of preparedness on caregiver burden, depression, and quality of life in caregivers of people with disabilities. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1153588 (2023).

Dal Pizzol, F. L. F. et al. The meaning of preparedness for informal caregivers of older adults: A concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs.80 (6), 2308–2324 (2024).

Kristanti, M. S. et al. The experience of family caregivers of patients with cancer in an Asian country: A grounded theory approach. Palliat. Med.33 (6), 676–684 (2019).

Ross, A. et al. Factors that influence health-promoting behaviors in cancer caregivers. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 47 (6), 692–702 (2020).

Northouse, L. L. et al. The impact of caregiving on the psychological well-being of family caregivers and cancer patients. Semin. Oncol. Nurs.28 (4), 236–245 (2012).

Van Hoi, L. et al. Willingness to use and pay for options of care for community-dwelling older people in rural Vietnam. BMC Health Serv. Res.12 (1), 36 (2012).

Zarit, S. H. et al. Exploring the benefits of respite services to family caregivers: methodological issues and current findings. Aging Ment Health. 21 (3), 224–231 (2017).

Claramita, M. et al. Doctor-patient communication in Southeast Asia: a different culture? Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract.18 (1), 15–31 (2013).

Cai, J. A Robust Health System To Achieve Universal Health Coverage in Vietnam, 37 (The Lancet Regional Health – Western Pacific, 2023).

Giebel, C. et al. Community-based mental health interventions in low- and middle-income countries: a qualitative study with international experts. Int. J. Equity Health. 23 (1), 19 (2024).

Parry, S. J. & Wilkinson, E. Mental Health Serv. Cambodia: Overv. BJPsych Int., 17(2): 29–31. (2020).

Teteh, D. K. et al. Abstract B108: social determinants of health factors impact the psychological distress of lung cancer surgery patients and their family caregivers. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev.32 (1_Supplement), B108–B108 (2023).

Ketcher, D. et al. The psychosocial impact of spouse-caregiver chronic health conditions and personal history of cancer on well-being in patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. J. Pain Symptom Manage.62 (2), 303–311 (2021).

Vu, T., Van, N. & Ngo, V. Severity of mental health symptoms and association with well-being, social and caregiving factors among family caregivers of lung cancer patients in Vietnam. In APHA 2024 Annual Meeting and Exp (2024).

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Prof. Joseph P. Dario at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai for his comments on the manuscript. This work was partially presented at the 2024 American Public Health Association Annual Meeting and Expo in Minneapolis, entitled “Severity of mental health symptoms and association with well-being, social and caregiving factors among family caregivers of lung cancer patients in Vietnam64”.

Funding

This study is supported by the Cancer Epidemiology Education in Special Populations (R25CA112383), Weill Cornell Medicine Career Advancement for Research in Health Equity (CARE T37) program (1T37MD014220), Point Foundation’s BIPOC Scholar Awards, Professional Growth Award 2023 from Graduate Student Government Association and Dean’s Dissertation Award 2024 at CUNY School of Public Health and Health Policy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TTV contributed to the study conceptualization, design, data analyses, and writing of initial drafting of this manuscript. VKN, GJ, SF, and VTN provided feedback on earlier versions. TTV revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at Hanoi University of Public Health, Vietnam (211/2023/YTCC-HD3) and City University of New York (2023-0754-PHHP), USA. The study was conducted in accordance with APA ethical guidelines for Human Subjects Research. All participating family caregivers voluntarily provided a written informed consent form.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vu, T.T., Johnson, G., Fleary, S. et al. Examining the relations between psychosocial and caregiving factors with mental health among Vietnamese family caregivers of hospitalized lung cancer patients. Sci Rep 15, 14078 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96409-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96409-5