Abstract

In the highly stressful environment of graduate medical residency, residents often grapple with anxiety, depression, and burnout. Those with intrinsic motivation, self-determination (SD), effective coping skills, and mindfulness may exhibit resilience against burnout and its negative effects on well-being. Using the SD theory framework, our study aims to explore the intricate relationship between motivation, stressors, and individual traits, aiming to predict burnout and mental distress among residents in training. We collected data from multispecialty residents through standardized questionnaires assessing SD, motivation, burnout, and mental distress. Structural equation models (SEM) were employed, on subsamples of high and low SD; model fits were checked. Various forms of motivation were tested as mediators between stressors, personality, and the three dimensions of burnout. In the overall sample of 112 participants, extrinsic motivation fully mediates the relation between stressors and low sense of personal accomplishment (indirect Beta = 0.02; p = 0.04). In the introject model, motivation fully mediates the relation between maladaptive coping and depersonalization (indirect Beta = 0.10; p = 0.03). In the intrinsic motivation model, motivation fully mediates the relation between adaptive (indirect Beta = 0.13; p < 0.001), maladaptive coping (indirect Beta = − 0.15; p = 0.01) and depersonalization (indirect Beta = − 0.31; p > 0.001). Among the low SD subgroup, a full mediation effect was found for extrinsic motivation between stressors and depersonalization (indirect Beta = 0.07; p = 0.027) and for intrinsic motivation between adaptive coping and depersonalization (indirect Beta = 0.150; p = 0.014). In the high SD subgroup, mindfulness has a moderation effect on burnout dimensions, positively on the relation between maladaptive coping and depersonalization and negatively on maladaptive coping and emotional exhaustion in the intrinsic and introject models. In both the low and high SD subgroups, regardless of motivation type, emotional exhaustion correlates with anxiety and depression, while depersonalization negatively correlated with mental distress. The presence of SD moderated the effect of stressors on burnout. Mindfulness plays a crucial role in buffering the effect of maladaptive coping on the various dimensions of burnout, linked in its turn to depression and anxiety symptomatology. Mindfulness also exerts a direct inverse effect on personal exhaustion in the low SD subgroup. Further studies are suggested to confirm these findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Graduate medical education, commonly referred to as residency, is a challenging period in the life of a medical professional. It is marked by intense work and study demands, long working hours, increased patient duties and erratic sleeping1,2. This intense chronic stress increases the risk of stress-related disorders including burnout, anxiety and depression2,3.

Burnout is defined as “a pathological syndrome in which emotional depletion and maladaptive detachment develop in response to prolonged occupational stress”. It is believed to have three distinct dimensions, starting with (1) emotional exhaustion-feeling overextended and fatigued at work, leading to (2) depersonalization, which is the development of a callous, cynical and dehumanized perception of others and finally (3) a low sense of accomplishment, which is dissatisfaction with one’s work-related achievements4,5. When stress becomes chronic, rates of burnout increase. Among residents at the end of the first year of residency, burnout prevalence can reach 55%, and this can persist in certain cases until the end of residency3. The ensuing burnout is known to put residents at a greater risk of making medical errors and it affects their abilities to make adequate patient-related decisions3,6.

The phenomenon of burnout among residents is a global concern, with varying prevalence rates in different regions between 3% and reaching up to 88%. It is notably highest in the Middle East and Africa7. This variability may be attributed to differences in healthcare systems, cultural factors, or other related variables, as suggested by Keroack et al. and Vendeloo et al8,9. In addition to the common stressors typically associated with residency, trainees in the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region, including Lebanon, face the added challenge of working in conflict-affected areas and sometimes with inadequate infrastructure6,10.

Lebanon, a small country in the Middle East, has endured decades of armed conflicts and instability. More recently, since 2019, the nation has been grappling with an unprecedented socio-political crisis, a severe economic downturn that has led to a significant devaluation of the local currency, and the devastating Beirut port explosion, which inflicted substantial damage on half of the capital city and severely incapacitated major hospitals located there. These tragedies resulted in additional trauma, loss of life, and widespread distress. Lebanon has also had to manage an influx of 2 million Syrian refugees, a significant number for a nation with a population of 6 million Lebanese11. These accumulating adversities have placed tremendous strain on the entire workforce, and particularly those working in the healthcare sector, further exacerbating their mental health challenges. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has added a substantial burden to the personal, clinical, and procedural workload of residents11.

Recent studies have unveiled a concerning prevalence of burnout in Lebanon with rates reaching up to 86% among healthcare providers in general and up to 68% among postgraduate medical trainees, in particular12. Furthermore, many residents have resorted to self-treatment with psychotropic medications6,13. Factors contributing to this escalating public health threat include excessively long working hours following the pandemic, the fear of infection, concerns about infecting family and friends, and the rising cost of diesel for commuting to work6.

Moreover well-being of residents becomes an important institutional asset as it directly and indirectly impacts their performance, safety behaviors and the quality of care they provide10,14,15. As such, the scientific community has started investigating potential protective mechanisms to combat workplace burnout16,17. Organizational factors promoted include favorable learning environments as well as workplace demands such as workload and working hours9. The ACGME 2003 guidelines championed policies restricting work hours to less than 80 h a week. Studies have also advocated increased connection via providing support, mentoring or even programmatic social events9,17,18. Yet again, some personality factors accounted for the heterogenous accounts of burnout19,20.

Of the personal predictors of burnout in the healthcare profession, investigators have initially looked at demographic predictors. It was shown that younger professionals, particularly women, who had to care for loved ones at home (kids or elderly) had higher reports of burnout12. The same authors further demonstrate that burnout levels were worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic by factors such as contracting the virus, working extensive hours and inadequate sleep patterns. Additional factors have been investigated concerning burnout including coping, personality traits and motivation among others. Several studies have in fact shown that the presence of social relationships is one major coping mechanism for stressful life events21,22. Individuals with active social support systems may be able to open up to others about what’s going on in their lives, allowing them to buffer or channel their negative emotions into something more sportive21,22. Openness, being able to engage in problem-solving with others and the ability to positively interpret interactions have been suggested as means to reduce their anxiety and, consequently, burnout23. Medical students particularly seem to cope with stress by engaging in extracurricular activities, having supportive mentorship programs, and finding social outlets for personal tensions24. In this optic, research has shown that SD, which means having a choice in the intentionality of behavior and thus willingly engaging in a meaningful activity, correlates with better performance and with less burnout, specifically in demanding professions like athletics and healthcare25,26. Moreover, mindfulness, which is also based on intentionality and awareness of one’s thoughts, has also shown promising results in buffering the negative effect of burnout in medical residents27.

Yet, as promising as it may be to address the global threat of burnout, the role of SD, frequently studied with facets of motivation in the mitigation of burnout in residents, remains under-explored.

The SD theory as a framework

This theoretical framework addresses the productivity, achievement or performance of individuals on a given task28. It posits that individuals need the satisfaction of three basic psychological needs (BpN): autonomy (feeling of choice), competence (sense of capability) and relatedness (sense of belonging), to be productive and motivated at work28. This theory asserts that the type of motivation or its quality is implicated in the performance. This theory has been validated in a health-related environment by Johan Y et al., where self-determined individuals have improved physical and mental well-being29. SD also seems to dampen burnout and ameliorate the overall patient-doctor relationship29. Self-Determination Theory (SDT) describes motivation as existing on a continuum of self-determination, ranging from no or low self-determination (amotivation or extrinsic motivation) to high self-determination (intrinsic motivation). The types of motivation —extrinsic, introject and intrinsic motivation—can be mapped to this continuum based on the degree of satisfaction of the three basic psychological needs, competence, relatedness and autonomy.

Given the multiple crises faced by residents in Lebanon, ranging from political unrest and revolution to the economic meltdown, the COVID-19 pandemic and the Beirut Blast, it is important to investigate the exact roles SD and motivation play in predicting burnout in a critical population. Interestingly, the study by Youssef et al., (2022) seems to indicate that different factors predict the various dimensions of burnout (personal, work and client) in more than 1300 healthcare providers12. As such, the present study will include a differential investigation of the impact of the aforementioned variable on each of the three facets of burnout: depersonalization, exhaustion and personal accomplishment.

The present study

Extensive evidence in the literature indicates that external stressors are strongly linked to burnout, which can subsequently result in reduced performance, and potentially lead to depression and anxiety. However, the role of individual personality traits in mediating or moderating this pathway remains relatively underexplored, particularly within the context of medical residents’ training.

In this study, we aim to investigate the relationship between significant collective stressors, individual differences in coping mechanisms, and burnout among residents. We will examine this relationship in individuals with both low and high levels of SD, utilizing motivation as a potential mediator and mindfulness as a potential moderator.

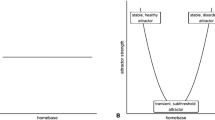

In Fig. 1, we propose that cumulative environmental stressors/trauma, along with both adaptive and maladaptive coping mechanisms, would directly affect burnout and self-perceived performance and indirectly affect them through the mediation of motivational subsets. In turn, both burnout and self-perceived performance contribute to the development of symptoms of depression and anxiety. Mindfulness, on the other hand, would differentially interact with the trauma, coping and burnout relationships.

To better address the gap in the literature vis-à-vis the roles of motivation and SD in the pathway to different dimensions of burnout, and to reproduce existing literature in the unprecedented Lebanese context with superimposed crises, we hypothesize that:

-

1.

Since SDT emphasizes that the satisfaction of basic psychological needs (autonomy, competence, and relatedness) is essential for well-being, environmental stressors, such as collective traumas, can threaten these needs by creating feelings of helplessness (undermining competence), loss of control (undermining autonomy), and social disconnection (undermining relatedness). When these needs are frustrated, individuals are more likely to experience burnout, characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment. Additionally, need frustration is linked to increased anxious and depressive symptomatology, as the inability to fulfill these needs exacerbates psychological distress.

→ Various collective traumas referred to as environmental stressors, would predict higher burnout aspects among residents, with increased anxiety and depressive symptomatology.

-

2.

SDT distinguishes between types of motivation which influence how individuals respond to stressors. Intrinsic motivation, generally in parallel with high SD, is associated with adaptive coping and resilience, potentially buffering the impact of stressors on burnout whereas extrinsic and introjected motivation (low to moderate SD) are more likely to exacerbate burnout, as they are driven by external pressures or internalized guilt, which can increase stress and emotional exhaustion.

→ Types of motivation (extrinsic, introject and intrinsic) would have differential effects as mediators between the stressors and the three dimensions of burnout, with intrinsic motivation acting as a protective factor and extrinsic/introjected motivation as risk factors.

-

3.

SDT suggests that the satisfaction of basic needs (autonomy, competence and relatedness) fosters adaptive coping strategies (e.g., problem-solving, seeking social support), while need frustration leads to maladaptive coping strategies (e.g., avoidance, denial).

→ Burnout would also be influenced by adaptive or maladaptive coping strategies; this relationship would be distinctly mediated by separate constructs of motivation, with adaptive coping and autonomous motivation acting as protective factors.

-

4.

SDT posits that the degree of self-determination (satisfaction of the BPN or frustration of the BPN) influences how motivation impacts outcomes. High SD (i.e. satisfaction of the BPN) negatively moderates the effect of stressors on burnout determinants especially in individuals with intrinsic motivation whereas in the setting of low SD (BPN frustration) stressors predict burnout more so in individuals with extrinsic or introject motivation.

→ Low and high levels of SD would in turn moderate the effect of various forms of motivation on burnout.

-

5.

Finally, SDT highlights the importance of awareness and autonomy in promoting well-being. Mindfulness, which involves present-moment awareness and non-judgmental acceptance, aligns with these principles. Mindfulness can enhance autonomy by helping individuals respond to stressors with greater intentionality rather than reactivity. It also promotes adaptive coping strategies by reducing emotional reactivity and increasing cognitive flexibility.

→ Mindfulness would have a moderating effect on the relation between stressors and coping strategies as independent variables and burnout as the dependent one, therefore acting as a protective factor, reducing the negative impact of stressors and maladaptive coping on burnout

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This is an observational study in which 112 multi-specialty residents from various residency training programs across Lebanon using the snowball effect, participated. The data was collected over 1 year. Residents in training from different various programs were included. There were no preset exclusion criteria.

Procedure and ethical aspects

Participants were recruited by sending an online invitation with a link to an anonymous survey that was disseminated using various social media platforms and data handling was done in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board committee (LAU.SOM.RC1.30/Dec/2020). All data collected was anonymous and available only to the investigators in the study.

Study population

After providing their consent, participants were asked to about the extent they and their families were exposed to or affected by the various crises (COVID, Beirut blast, economic collapse) and the level of stress and support at work. Residents also answered questions about coping mechanism they applied most frequently during the pandemic. The questions addressed both adaptive and maladaptive coping mechanisms followed by standardized questionnaires. The former included aspects of Adaptive coping behaviors such as getting enough sleep, exercising and spending time with family and friends. For the maladaptive coping, items like smoking, using tranquilizers and drinking were used.

Questionnaires

MBI (The Maslach Burnout Inventory) (Maslach et al.5). It is a validated 22-item questionnaire used to assess workplace burnout. It measures three dimensions of burnout which are independent constructs: depersonalization [Dp; 5 items], (lack of) personal accomplishment [pA; 8 items] and emotional exhaustion [EE; 9 items]. Each item is answered on a frequency scale ranging from (1) ‘never’, (2) ‘a few times a year or less’, (3) ‘once or less a month’, (4) ‘a few times a month’, (5) ‘once a week’, (6) ‘a few times a week’ to (7) ‘every day’. Examples of questions: ‘Working with people all day is a strain for me”. Individuals are considered to have a burnout if they have higher scores on either EE (total score of > = 27) or Dp (total score of > = 10) (Schaufeli et al., 2001; Wickramasinghe et al., 2018) or if individuals have high EE score plus either a high Dp score or a low pA score (pA score less than 33) (Dyrbye et al., 2009). If they score between 0 and 18 on EE, or 0–5 on Dp or pA higher than 40, they are considered to have low levels of burnout.

BpNS (Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction)30. It is a standardized 21-item questionnaire based on the SD theory. It assesses satisfaction and frustration with three main needs: competence, autonomy, and relatedness (Liga et al., 2018). For the subsequent path analysis, residents were grouped into low SD (autonomy, competence and relatedness frustration) and high SD groups (autonomy, competence and relatedness satisfaction).

PHQ-4 (The Patient Health Questionnaire)31. It is an ultra-brief self-report questionnaire that consists of a 2-item depression scale (PHQ-2) and a 2-item anxiety scale (GAD-2). All items are scored from 0 to 3 depending on the frequency patients have been bothered by the symptoms over the preceding two weeks. In screening for depression and anxiety, a cutoff ≥ 3 in GAD-2 and PHQ-2 is recommended32.

MWMS (Multidimensional Work Motivation Scale)33. It is a standardized questionnaire consisting of six constructs of motivation; 3 of which were chosen for this study: external, introject, and intrinsic motivation.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were carried out using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (version 24.0 with AMOS; IBM®, Armonk, NY, U.S.A.). For descriptive analysis, frequency and percentage were used for categorical variables and mean and standard deviation for quantitative variables.

Structural equation modelling (SEM) was also performed to examine the structural relationship between stressors, adaptive and maladaptive coping taken as independent variables, burnout, depression/anxiety and self-performance as the dependent variables, motivation as the mediator variable and mindfulness as the MOD variables. The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) statistics, Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) and the comparative fit index (CFI) were used to evaluate the goodness-of-fit of the model. A good model data fit is indicated by RMSEA < 0.06, CFI > 0.95, and TLI > 0.95 (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

The model adhered to SEM assumptions, with three continuous, normally distributed dependent variables and well-defined cause-and-effect relationships between endogenous and exogenous variables. No outliers were detected, and uncorrelated error terms preserved estimate integrity. Model fit indices in the results confirmed the suitability of SEM for this study. (Supplementary material). In all cases, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

MBI score distribution overall and in the SD subgroups

MBI data analysis showed an alarming level of burnout in the sample population studied, where 75% of participants scored high for depersonalization and emotional exhaustion, and low levels of personal accomplishment (Table 1). The mean score of depersonalization in the overall sample was 30.03 ± 6.9, for low personal achievement was 12.79 ± 5.38 and for personal exhaustion was 33.81 ± 11.29 (Table 1). When subgroup analysis according to level of self-determination was performed, significantly worse levels of depersonalization and low sense of personal achievement were noted in the high self-determination group (33.01 ± 5.57, P-value < 0.001 and 11.37 ± 5.28, P-value 0.028 respectively). Personal exhaustion, however, was significantly higher among the low self-determination group 37.25 ± 9.07 versus 30.32 ± 12.2 in the high self-determination group (P-value 0.001) (Table 2).

The structural equation model for the overall group

Table 3 depicts the findings of the structural equation models conducted in the overall group of residents. Results show motivation differentially influences the paths studied. No direct association was found between stressors and coping with burnout dimensions.

In the extrinsic motivation model, stressors have a significant influence on motivation (B 0.086, p = 0.037). In turn, motivation was significantly associated with a higher score of a low sense of personal accomplishment (Beta = 0.276, p = 0.003). Therefore, motivation fully mediates the relation between stressors and low sense of personal accomplishment (indirect Beta = 0.02; p = 0.04).

In the introject model, maladaptive coping is significantly related to lower motivation (Beta = − 0.207, p = 0.025). In turn, motivation is significantly related to higher depersonalization (Beta = 0.511, p = 0.005). Motivation fully mediates the relation between maladaptive coping and depersonalization (indirect Beta = 0.10; p = 0.03).

In the intrinsic motivation group, both adaptive (B 0.231, p = < 0.001) and maladaptive mechanisms (B − 0.263 p = 0.034) have significant effects on motivation. In turn, motivation is significantly associated with depersonalization (Beta = 0.577, p < 0.001). Motivation fully mediates the relation between adaptive (indirect Beta = 0.13; p < 0.001), maladaptive coping (indirect Beta = − 0.15; p = 0.01) and depersonalization.

There is no interaction between mindfulness on stressors, coping and the dimensions of burnout. Therefore, mindfulness does not have a moderation effect on the relation between stressors, coping and burnout dimensions.

Finally, whereas depersonalization is negatively associated with depression and anxiety symptomatology in all the studied models of motivation (Beta = − 0.131, p = < 0.001), emotional exhaustion is significantly associated with depression and anxiety symptoms in all the studied models of motivation (Beta = 0.163, p = < 0.001). The various relationships, mediation and moderation are shown clearly in Fig. 2.

Association between stressors, coping with burnout dimensions mediated by the types of motivation and moderated by mindfulness. The figure presents the association between burnout dimension and depression/anxiety. The numbers in the figure represent the association between the variables definite in Beta as follows: (1) Association between stressors and types of motivation, Beta intrinsic = − 0.020, Beta extrinsic = 0.086*, Beta introject = − 0.039. (2) Association between adaptive coping and types of motivation, Beta intrinsic = 0.231*, Beta extrinsic = − 0.033, Beta introject = − 0.040. (3) Association between maladaptive coping and types of motivation, Beta intrinsic = − 0.263*, Beta extrinsic = 0.191, Beta introject = − 0.207*. (4) Association between motivation and personal exhaustion: Beta intrinsic = − 0.374; Beta extrinsic = 0.139, Beta introject = 0.048. Association between motivation and personal achievement: Beta intrinsic = − 0.106, Beta extrinsic = 0.276*, Beta introject = − 0.206. Association between motivation and depersonalization: Beta intrinsic = 0.577*, Beta extrinsic = 0.187, Beta introject = 0.511*. (5) Association between stressors and burnout in the extrinsic model: Beta personal exhaustion = − 0.143 Beta personal achievement = − 0.036, Beta depersonalization = 0.021. Association between stressors and burnout in the intrinsic model: Beta personal exhaustion = − 0.191 Beta personal achievement = − 0.010 Beta depersonalization = 0.165. Association between stressors and burnout in the introject model: Beta personal exhaustion = − 0.123 Beta personal achievement = 0.028, Beta depersonalization = 0.010. (6) Association between adaptive coping and burnout in the extrinsic model: Beta personal exhaustion = − 0.597 Beta personal achievement = − 0.135, Beta depersonalization = 0.133. Association between adaptive coping and burnout in the intrinsic model: Beta personal exhaustion = − 0.451 Beta personal achievement = − 0.153, Beta depersonalization = − 0.194. Association between adaptive coping and burnout in the introject model: Beta personal exhaustion = − 0.123 Beta personal achievement = 0.028, Beta depersonalization = 0.010. (7) Association between maladaptive coping and burnout in the extrinsic model: Beta personal exhaustion = − 0.109 Beta personal achievement = − 0.320, Beta depersonalization = 0.523. Association between maladaptive coping and burnout in the intrinsic model: Beta personal exhaustion = 1.305 Beta personal achievement = 0.425, Beta depersonalization = 0.304. Association between maladaptive coping and burnout in the introject model: Beta personal exhaustion = 1.140 Beta personal achievement = − 0.373, Beta depersonalization = 0.574. (8) Association between the interaction of stressors and mindfulness with burnout in the extrinsic model: Beta personal exhaustion = 0.026 Beta personal achievement = 0.010, Beta depersonalization = 0.001. Association between the interaction of stressors and mindfulness with burnout in the intrinsic model: Beta personal exhaustion = 0.032 Beta personal achievement = 0.009, Beta depersonalization = − 0.012. Association between the interaction of stressors and mindfulness with burnout in the introject model: Beta personal exhaustion = 0.025 Beta personal achievement = 0.004, Beta depersonalization = 0.006. (9) Association between the interaction of adaptive coping and mindfulness with burnout in the extrinsic model: Beta personal exhaustion = 0.014 Beta personal achievement = 0.001, Beta depersonalization = − 0.010. Association between the interaction of adaptive coping and mindfulness with burnout in the intrinsic model: Beta personal exhaustion = 0.005 Beta personal achievement = 0.005, Beta depersonalization = 0.016. Association between the interaction of adaptive coping and mindfulness with burnout in the introject model: Beta personal exhaustion = 0.018 Beta personal achievement = 0.009, Beta depersonalization = − 0.003. (10) Association between the interaction of maladaptive coping and mindfulness with burnout in the extrinsic model: Beta personal exhaustion = − 0.073 Beta personal achievement = − 0.003, Beta depersonalization = − 0.078. Association between the interaction of adaptive coping and mindfulness with burnout in the intrinsic model: Beta personal exhaustion = − 0.103 Beta personal achievement = − 0.012, Beta depersonalization = − 0.032. Association between the interaction of adaptive coping and mindfulness with burnout in the introject model: Beta personal exhaustion = − 0.072 Beta personal achievement = − 0.008, Beta depersonalization = − 0.067. (11) Association between burnout and depression/ anxiety: Beta personal exhaustion = 0.163* Beta personal achievement = − 0.036, Beta depersonalization = − 0.131*. The Bold and Asterix values * Indicate significant values p < 0.05.

To better answer our hypotheses and build cohesive models accordingly, the path analysis was established separately for low and high SD subgroups.

Stratified by high/low self-determination group

High SD subgroup

Extrinsic motivation

Results show that for residents with high SD, maladaptive coping negatively relates to depersonalization, i.e. it lessened this aspect of burnout (Beta = − 1.326, p = 0.045). A positive correlation is also found between extrinsic motivation and a low sense of personal accomplishment (Beta = 0.337, p = 0.003). No mediation effect of motivation between stressors, coping and burnout dimensions was found (Table 4).

Mindfulness shows a borderline significant moderation effect on maladaptive coping and emotional exhaustion (Beta = – 0.260, p = 0.051).

Emotional exhaustion correlates positively with depression/ anxiety symptoms (Beta = 0.144, p = < 0.001) whereas depersonalization correlates negatively with mental distress (Beta = − 0.162, p = 0.012) (Table 4).

Introject motivation

Motivation positively correlates with depersonalization (Beta = 0.550, p = 0.009) whereas maladaptive coping negatively correlates with depersonalization (Beta = – 1.789, p = 0.005).

Mindfulness has a positive interaction between maladaptive coping and depersonalization (Beta = 0.145, p = 0.014). It also has a negative interaction between maladaptive coping and emotional exhaustion (Beta = – 0.266, p = 0.047).

As per the extrinsic motivation, emotional exhaustion correlates positively with depression and anxiety symptoms (Beta = 0.144, p < 0.001) whereas depersonalization negatively correlates with mental distress (Beta = − 0.162, p = 0.011) (Table 4).

Intrinsic motivation

Maladaptive coping negatively correlates with depersonalization (Beta = − 1.593, p = 0.013) and positively correlates with emotional exhaustion (Beta = 2.866, p = 0.044).

Intrinsic motivation has a positive correlation with depersonalization (Beta = 0.391, p = 0.019).

Mindfulness has a moderation effect on burnout dimensions as it positively moderates the relation between maladaptive coping and depersonalization (Beta = 0.125, p = 0.035) and exerts negative moderation on maladaptive coping and emotional exhaustion (Beta = − 0.311, p = 0.019).

Consistent with the above, emotional exhaustion correlates positively with depression and anxiety symptoms (Beta = 0.144, p < 0.001) whereas depersonalization negatively correlates with mental distress (Beta = − 0.162, p = 0.013) (Table 4).

Low SD subgroup

Extrinsic motivation

Results show that for residents in the low self-determined group, external stressors positively correlate with extrinsic motivation (B 0.133, p = 0.021) which in turn directly correlates with depersonalization (Beta = 0.534, p = 0.002) and personal accomplishment (Beta = 0.297, p = 0.040). A full mediation effect was found for motivation between stressors and depersonalization (indirect Beta = 0.07; p = 0.027) (Table 5).

Additionally, adaptive coping negatively correlates with a low sense of personal accomplishment (Beta = -0.670, p = 0.028) whereas maladaptive coping positively correlates to depersonalization, worsening it (Beta = 1.861, p = 0.002).

Our results show that mindfulness has a moderation effect on adaptive coping and a low sense of personal accomplishment (Beta = 0.073, p = 0.025) meaning that for mindful residents, adaptive coping further reduces the low sense of personal accomplishment. Furthermore, mindfulness exerts a negative moderation effect on maladaptive coping and depersonalization (B − 0.223, p = 0.004) i.e. decreasing the impact of maladaptive coping (such as denial and substance use) on burnout. In addition, mindfulness was significantly negatively associated with emotional exhaustion (B − 4.752, p = 0.016).

Data also reveals a significant correlation between emotional exhaustion and depression/anxiety (Beta = 0.162, p = < 0.001) (Table 5).

Introject motivation

We observe a positive association between maladaptive coping and depersonalization (Beta = 1.909, p = 0.003) (Table 5).

Once again, mindfulness is found to have a direct negative association with emotional exhaustion (Beta = − 4.735, p = 0.016). It also protects against burnout indirectly by moderating the relation between adaptive coping and the low sense of personal accomplishment (Beta = 0.072, p = 0.034), while negatively moderating the relation between maladaptive coping and depersonalization (Beta = − 0.208, p = 0.011).

Like the extrinsic motivation model, emotional exhaustion is significantly associated with depression/ anxiety symptomatology (Beta = 0.162, p = < 0.001) (Table 5).

Intrinsic motivation

Adaptive coping positively impacts motivation (Beta = 0.277, p = 0.005) which in turn directly correlates with depersonalization (Beta = 0.542, p = 0.003). A full mediation effect is found for motivation between adaptive coping and depersonalization (indirect Beta = 0.150; p = 0.014) (Table 5).

Maladaptive coping is significantly associated with depersonalization (Beta = 1.534 p = 0.011), (Table 5).

Similar to the above two motivation models, mindfulness5 has a moderate effect. It shows a significant direct negative association with emotional exhaustion (B – 4.526, p = 0.020), while it indirectly moderates the relation between maladaptive coping and depersonalization (Beta = − 0.165, p = 0.032) (Table 5).

Consistent with the above, those with emotional exhaustion are significantly associated with depression/ anxiety symptomatology (Beta = 0.162, p = < 0.001).

Discussion

Using the SD theoretical framework28, this study investigates the predictors of burnout in a medical resident population from various specialties under particularly challenging accumulating stressors. While burnout is known to pose a significant threat to the well-being and performance of those residents, personal behaviors, including coping strategies and the level of environmental support for the three psychological needs that either facilitate or thwart SD, may serve as buffers or exacerbate the resulting burnout across its different dimensions. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first attempt to examine the intricate and complex interplay between SD, motivation, coping strategies, and stress levels on one hand and the various dimensions of burnout on another.

By conducting an advanced path analysis, we found each of the different types of motivation investigated mediate the relationship between stress, coping and burnout differently. We have also examined the role of mindfulness as a moderator and most importantly highlighted the impact of SD on this pathway.

Environmental stressors, motivation and burnout

First and foremost, our results show alarming rates of burnout and mental distress in the overall group of Lebanese residents in the range of 75% total burnout, anxiety and depression symptoms. This is in agreement with reports in the global literature whereby COVID has further inflated existing levels of burnout among healthcare providers as a group by up to 65% with a higher risk for medical learners in particular34. Similarly, a recent study published in 2022 on Lebanese healthcare workers reported a prevalence of 86.3% of moderate to high-level burnout12.

When looking at the overall group of residents, our data further shows that different types of motivation have differential effects in mediating the relationship between stressors and the three dimensions of burnout. According to the SD theory, the degree of motivation is on a continuum with amotivation and autonomous motivation on extremes and controlled motivation in between, all having different foci of control28. This means that for extrinsic motivation, the regulation is externally controlled, and as it progresses on the continuum towards introjected and intrinsic, the focus of regulation becomes increasingly autonomous. In our study, we have observed that stressors have a positive effect only on extrinsic motivation, increasing it. Extrinsic motivation fully mediates the effect of external urban stressors on the low sense of personal accomplishment dimension of burnout with the latter predicting anxiety and depression. In other words, in the setting of challenging circumstances, residents relying on external sources of motivation to perform well in their jobs are more likely to feel burned out and inefficient as environmental stressors accumulate, as opposed to those who have internalized their motivation to attend to work. This finding comes in support of previous research on motivational theories, including the SD theory, which has shown that extrinsic and intrinsic motivation bifurcate at the psychological level and have different roles in the mediation of burnout, with extrinsic motivation playing a positive role in burnout and inflating it while intrinsic motivation playing a negative role and dampening it25,35. Those extrinsically motivated have their drive to perform or achieve based on external rewards and expectations, and thus when exposed to unprecedented demanding conditions and stressors, may feel overburdened and pushed to burnout with depleted external reinforcers.

Therefore, our first hypothesis, which posits that various collective traumas referred to as environmental stressors, predicts higher burnout aspects among residents, with increased anxious and depressive symptomatology is fully supported.

On the other hand, introject and intrinsic motivation mediated the effect of coping mechanisms on the depersonalization dimension of burnout. In these groups of residents, it was their behaviors and the strategies they used to manage the stress that played a critical role not only in their level of motivation but also in developing burnout. Whether with introject or intrinsic motivation, maladaptive coping led to lower motivation which in turn resulted in worsening depersonalization. In the intrinsic motivation group, adaptive coping had a significant positive effect on motivation. It is interesting to note that introject regulation, which is within the spectrum of controlled motivation, predicted a similar burnout outcome as that of intrinsic motivation, asserting that the focus of regulation of introject motivation is much closer to autonomy than that of the extrinsic motivation. From a psychological perspective, individuals resolving maladaptive coping strategies are at risk of lower motivation worsening their risk of depersonalization. Therefore, our second hypothesis, that extrinsic, introject and intrinsic motivation have differential effects in mediating the relationship between stressors and the three dimensions of burnout, is also fully supported. Similarly, our third hypothesis that coping influences burnout through the differential mediation modes of motivation is also supported.

Low and high SD subgroups

Although counterintuitive, our research further highlights that, residents with high SD experience more depersonalization and a lower sense of personal achievement than those with low SD. This could be best understood by acknowledging the role of other factors beyond SD, such as workload, contextual demands and personal individual resources. In this perspective, as posited by models such as the job-demands resources model (Bakker et al., 2007), residents with a high sense of SD would drive self-determined ambitious residents to systematically invest more effort and personal resources into their work, exceeding their available capacity. In the long run, with the chronicity of increased demands, their cognitive and emotional resources might be depleted and their inability to achieve their set goals might lead to both fatigue and burnout symptoms like emotional detachment (depersonalization) and reduced feelings of accomplishment.

When subgrouping the residents according to the level of satisfaction of the three psychological needs, the core of the SD theory, our data reveals that SD plays a significant role in moderating the pathway to burnout. So, whereas external stressors and adaptive and maladaptive coping have significant direct and/or indirect mediation roles in the development of burnout in the low self-determined subgroup, only maladaptive coping has a direct mediation role in burnout in residents with high SD. This finding is in agreement with others that have shown that SD plays an important role in the development of burnout in various fields such as in athletes and PhD students in medicine26,36,36.

In residents with low SD, motivation fully mediates the effect of stressors on the depersonalization and personal accomplishment dimensions of burnout. To note, the impact of external stressors on motivation is only noticeable in this low self-determined group and among residents with extrinsic forms of motivation. In this group of residents, the motivation to perform is driven by external drivers or rewards. When such rewards are depleted, such as during an economic meltdown or when the work demands are further augmented such as during COVID or the blast, their ability to sustain the commitment may be overloaded and their resilience eroded rendering them susceptible to burnout.

Furthermore, different coping strategies play different roles in the mediation of various dimensions of burnout. Whereas in the low self-determined trainees, resolving to maladaptive coping strategies (eg. drinking, smoking or using pills to soothe) augments their depersonalization regardless of the types of motivation, be it extrinsic, introject or intrinsic motivation, adaptive coping seems to lessen the extent of low sense of personal accomplishment. Previous studies in teachers have shown that different coping strategies influence burnout and that depersonalization necessitates the use of coping that allows passive acceptance of stressful events37.

Unlike the low SD subgroup, it is only maladaptive coping that negatively mediates the depersonalization dimension of burnout regardless of motivation type among these residents. However, for those with intrinsic motivation, maladaptive coping further puts them at risk for an additional dimension of burnout, emotional exhaustion. In fact, data also reveals that the more autonomous motivation (introject and intrinsic), the more the risk for depersonalization and the more controlled motivation, i.e. extrinsic motivation, the more the risk for the low sense of personal accomplishment.

Therefore, our third hypothesis that burnout is influenced by adaptive or maladaptive coping strategies and that this relationship would be distinctly mediated by separate constructs of motivation is fully supported. Furthermore, our fourth hypothesis SD moderates the effects of various forms of motivation on burnout is also supported.

Interestingly, depending on the subgroup of SD, mindfulness has a divergent impact on burnout, both directly and indirectly. In the low SD subgroup, mindfulness seems to tune down the maladaptive coping impact on burnout in all forms of motivation whereas it tunes up the adaptive coping impact on burnout in those with extrinsic and introject motivation. Furthermore, in this same group of residents, mindfulness exerts a direct inverse effect on emotional exhaustion across all forms of motivation. This is in line with previous research in forensic healthcare professionals where mindfulness led to lower emotional exhaustion and depersonalization38.

In the high SD subgroup, mindfulness exerts a positive moderation on maladaptive coping and depersonalization in introject and intrinsically motivated trainees. In other words, when the psychological needs are met, and high on the autonomous motivation scale, being more aware of hefty circumstances and the limitation of resources leads these residents to depersonalization, the external manifestation of burnout, whereby they would distance themselves from colleagues and patients and become more cynical-in as much as they rely on maladaptive coping strategies. On the other hand, mindfulness tunes down the effect of the drive of maladaptive coping towards emotional exhaustion.

Therefore, our fifth hypothesis, that mindfulness would have a moderating effect on the relation between stressors and coping strategies as independent variables and burnout as the dependent one, is fully supported. To note, specifically in the low SD subgroup, mindfulness decreases emotional exhaustion, something that we did not hypothesize.

Predictors of anxiety and depression

In both the low and high SD subgroups, regardless of the type of motivation, emotional exhaustion correlates with anxiety and depression. On the other hand, depersonalization inversely correlates with anxiety and depression symptomatology in the high SD subgroup. This is in agreement with reports in the literature that have shown that emotional exhaustion alone or with depersonalization are the dimension(s) most strongly associated with these mental health conditions and depressive symptomatology39,40. This finding may be related to the Lebanese context in particular or to residents in general. In general, residents tend to have high expectations for themselves and if they are not achieving their goals may end up doubting themselves and their abilities and thus get anxious or depressed. The stressful circumstances residents find themselves living through in Lebanon lend them a sense of powerlessness which may be another important contributor to the phenomenon of low sense of personal accomplishment being associated with anxiety and depression.

Limitations

The cross-sectional design rather than a longitudinal study limits the ability to establish causality and any changes over time. Inasmuch as the study portrays the alarming rates of mental distress, it uses self-reported measures rather than indices of behavior and health and as such is subject to subjectivity bias. Self-reported data may influence reporting on burnout measures through different mechanisms: social desirability leading to under-reporting to appear more resilient, negative response bias whereby trainees who face lots of stress may exaggerate their responses and recall bias due to lapse of time and hence inaccurate reporting. The increased COVID-19 infections at times of data collection prevented the recording of such objective measures. The small sample size selected in the current study may have limited the generalizability of our findings. The potential of a selection bias and the small sample size due to increased demand on residents make the results only generalizable with care, as future studies should include larger more heterogeneous groups of medical/ surgical residents, within and outside the Lebanese capital, to better understand the accumulating effects of adversities and external environments on burnout, SD and the coping strategies with distress. Finally, residual confounding is possible since many factors could not be taken into account within the analysis, given the low sample size and the instability of models with high numbers of predictors. Further studies are suggested to confirm these findings.

Conclusions and implications

Given the extremely elevated levels of burnout and mental distress among residents, a crucial segment of the healthcare workforce, it is thus critical for medical educators and policymakers to attend to this worrying silent pandemic.

With the backdrop of SDT, this study proposes a model that sheds light on how SD influences the way environmental stressors, coping strategies and motivation predict different dimensions of burnout among residents. Among trainees from environments that foster high SD, only maladaptive coping rendered them at risk for burnout. On the other hand, in residents whose SD is low, stressors and maladaptive coping render them susceptible to burnout.

In both subgroups, promoting mindfulness is important as it has a positive impact in lessening all facets of burnout regardless of type of motivation, both directly and indirectly. Of the three dimensions of burnout, residents with personal exhaustion are at high risk for the development of anxiety and depressive symptomatology.

Pending further confirmatory studies, our findings underscore the importance for educators involved in post-graduate education programs to endorse activities that promote SD starting with cultivating a supportive learning environment, one that grants trainees control over their learning experiences, provides assessments and constructive feedback and promotes empowerment of trainees. The programs are also encouraged to prioritize trainees’ wellbeing, incorporating mindfulness workshops as part of their personal development initiatives.

Data availability

All relevant data are available in an open access repository: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27287361.

References

Gazzaz, Z. J. et al. Perceived stress, reasons for and sources of stress among medical students at Rabigh Medical College, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. BMC Med. Educ. 18, 1–9 (2018).

Shete, A. N. & Garkal, K. D. A study of stress, anxiety, and depression among postgraduate medical students. CHRISMED J. Health Res. 2(2), 119–123 (2015).

Talih, F., Warakian, R., Ajaltouni, J., Shehab, A. A. S. & Tamim, H. Correlates of depression and burnout among residents in a Lebanese academic medical center: a cross-sectional study. Acad. Psychiatry 40, 38–45 (2016).

Maslach, C., Jackson, S. & Leiter, M. The Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. vol. 3, 191–218 (1997).

Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., Leiter, M. P., Schaufeli, W. B. & Schwab, R. L. Maslach Burnout Inventory: Manual: Includes These MBI Review Copies: Human Services-MBI-HSS, Medical Personnel-MBI-HSS (MP), Educators-MBI-ES, General-MBI-GS, Students-MBI-GS (S). (Mind Garden, 2017).

Ashkar, K., Romani, M., Musharrafieh, U. & Chaaya, M. Prevalence of burnout syndrome among medical residents: Experience of a developing country. Postgrad. Med. J. 86, 266–271 (2010).

Naji, L. et al. Global prevalence of burnout among postgraduate medical trainees: A systematic review and meta-regression. CMAJ Open 9, E189–E200 (2021).

Keroack, M. A. et al. Organizational factors associated with high performance in quality and safety in academic medical centers. Acad. Med. 82, 1178–1186 (2007).

van Vendeloo, S. N. et al. Resident burnout: Evaluating the role of the learning environment. BMC Med. Educ. 18, 54 (2018).

Chemali, Z. et al. Burnout among healthcare providers in the complex environment of the Middle East: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 19, 1–21 (2019).

El Khoury-Malhame, M., Rizk, R., Joukayem, E., Rechdan, A. & Sawma, T. The psychological impact of COVID-19 in a socio-politically unstable environment: Protective effects of sleep and gratitude in Lebanese adults. BMC Psychol. 11, 14 (2023).

Youssef, D., Abboud, E., Abou-Abbas, L., Hassan, H. & Youssef, J. Prevalence and correlates of burnout among Lebanese health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national cross-sectional survey. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 15, 102 (2022).

Yacoubian, A. et al. Burnout among postgraduate medical trainees in Lebanon: Potential strategies to promote wellbeing. Front. Public Health 10, 1045300 (2023).

Fawzy, M. & Hamed, S. A. Prevalence of psychological stress, depression and anxiety among medical students in Egypt. Psychiatry Res. 255, 186–194 (2017).

Panagioti, M. et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 178, 1317 (2018).

Janko, M. R. & Smeds, M. R. Burnout, depression, perceived stress, and self-efficacy in vascular surgery trainees. J. Vasc. Surg. 69, 1233–1242 (2019).

Prentice, S., Elliott, T., Dorstyn, D. & Benson, J. A qualitative exploration of burnout prevention and reduction strategies for general practice registrars. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 51, 895–901 (2022).

Bhananker, S. M. & Cullen, B. F. Resident work hours. Curr. Opin. Anesthesiol. 16, 603–609 (2003).

Amir, M., Dahye, K., Duane, C. & Ward, W. L. Medical student and resident burnout: A review of causes, effects, and prevention. J. Fam. Med. Dis. Prev. 4, 1–8 (2018).

Lee, Y. W., Kudva, K. G., Soh, M., Chew, Q. H. & Sim, K. Inter-relationships between burnout, personality and coping features in residents within an ACGME-I Accredited Psychiatry Residency Program. Asia-Pac. Psychiatry 14, e12413 (2022).

Jeong, Y. et al. The associations between social support, health-related behaviors, socioeconomic status and depression in medical students. Epidemiol. Health 32, e2010009 (2010).

Khodarahimi, S., Hashim, I. H. & Mohd-Zaharim, N. Perceived stress, positive-negative emotions, personal values and perceived social support in Malaysian undergraduate students. Int. J. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2, 1–8 (2012).

Sanchez-Ruiz, M.-J., Mavroveli, S. & Poullis, J. Trait emotional intelligence and its links to university performance: An examination. Personal. Individ. Differ. 54, 658–662 (2013).

Fares, J., Tabosh, H. A., Saadeddin, Z., Mouhayyar, C. E. & Aridi, H. Stress, burnout and coping strategies in preclinical medical students. North Am. J. Med. Sci. 8, 75 (2016).

Cresswell, S. L. & Eklund, R. C. Motivation and burnout in professional rugby players. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 76, 370–376 (2005).

Holmberg, P. M. & Sheridan, D. A. Self-determined motivation as a predictor of burnout among college athletes. Sport Psychol. 27, 177–187 (2013).

Lebares, C. C. et al. Feasibility of formal mindfulness-based stress-resilience training among surgery interns: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 153, e182734 (2018).

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. Self-determination theory. Handb. Theor. Soc. Psychol. 1, 416–436 (2012).

Ng, J. Y. et al. Self-determination theory applied to health contexts: A meta-analysis. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 7, 325–340 (2012).

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 11, 227–268 (2000).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W. & Löwe, B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ-4. Psychosomatics 50, 613–621 (2009).

Gagné, M. et al. The multidimensional work motivation scale: Validation evidence in seven languages and nine countries. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 24, 178–196 (2015).

Gottert, A. et al. Development and validation of a multi-dimensional scale to assess community health worker motivation. J. Glob. Health 11, 07008 (2021).

Denning, M. et al. Determinants of burnout and other aspects of psychological well-being in healthcare workers during the Covid-19 pandemic: A multinational cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 16, e0238666 (2021).

Morris, L. S., Grehl, M. M., Rutter, S. B., Mehta, M. & Westwater, M. L. On what motivates us: A detailed review of intrinsic v. extrinsic motivation. Psychol. Med. 52, 1801–1816 (2022).

Kusurkar, R. A. et al. Burnout and engagement among PhD students in medicine: The BEeP study. Perspect. Med. Educ. 10, 110–117 (2020).

Yin, H., Huang, S. & Lv, L. A multilevel analysis of job characteristics, emotion regulation, and teacher well-being: A job demands-resources model. Front. Psychol. 9, 2395 (2018).

Kriakous, S. A., Elliott, K. A. & Owen, R. Coping, mindfulness, stress, and burnout among forensic health care professionals. J. Forensic Psychol. Res. Pract. 19, 128–146 (2019).

Martínez, J. P., Méndez, I., Ruiz-Esteban, C., Fernández-Sogorb, A. & García-Fernández, J. M. Profiles of burnout, coping strategies and depressive symptomatology. Front. Psychol. 11, 591 (2020).

Mark, G. & Smith, A. P. Occupational stress, job characteristics, coping, and the mental health of nurses: Stress and nurses. Br. J. Health Psychol. 17, 505–521 (2012).

Acknowledgements

All participating residents

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.C: Study conception, helped with study design and study protocol, preparation of the questionnaire, contributed to the interpretation of analysis and wrote the manuscript. E.T: Helped in designing the study, preparation of the questionnaire, data collection, data entry and management, and manuscript preparation C.H: Data extraction, data management, conducted and reported all the structural equation models in the study PS: Data extraction, data management, statistical analysis study methods M.K: Helped with study design, preparation of the questionnaire, chose the measurement scales and instruments and helped in writing the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved it.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

The questionnaire and methodology of this study have been approved by the Institutional Research Board (IRB number (LAU.SOM.RC1.30/Dec/2020). All study participants have signed informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Towair, E., Haddad, C., Salameh, P. et al. Self-determination, motivation and burnout among residents in Lebanon. Sci Rep 15, 14248 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97028-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97028-w