Abstract

Historically overshadowed by communicable diseases, the burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) has surged over the past two decades, posing a significant threat to public health, and necessitating urgent attention. This study examines the mortality burden from four major groups/categories of NCDs including cancers, cardiovascular diseases (CVD), chronic respiratory diseases (CRD) and diabetes, prevalence of four NCD associated risk factors including tobacco use, alcohol consumption, physical inactivity and overweight, availability of NCD essential medicines and progress indicators of the NCD response in the WHO African region. The data used in this study were obtained from the WHO NCD data portal, Global Health Observatory, and Global Health Estimates, covering the most recent available data for each indicator, ranging from 2000 to 2019 to assess how trends in NCD mortality burden have evolved, as well as the current status of the four main risk factors, availability of essential medicines, and key NCD response indicators. The analysis focused on descriptive statistics for globally used, disease-specific key indicators to examine trends and variations across countries: (i) age-standardized mortality rates (ASMR) for major NCDs (cancers, CRD, CVD and diabetes), (ii) prevalence of NCD risk factors (tobacco use, alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, and overweight), (iii) availability of essential medicines for NCDs in public health facilities, and (iv) national NCD response indicators, such as the presence of NCD targets, mortality data, risk factor reduction measures, and surveillance. Mortality was reported as ASMR or percentages; risk factors as prevalence, except alcohol (litres per capita). Changes in mortality were calculated as absolute and relative differences, with tables and figures generated in Microsoft Excel. Between 2000–2019, NCD-related deaths and the percentage of deaths due to NCDs increased from 24.2 to 37.1% resulting in 12.9 and 53.3% absolute and relative increases. The ASMR decreased by 130.6 per 100,000 population resulting in an 18.2% relative decrease, during the same period; however, it remains consistently higher than the global average. In 2019, 64% of NCD deaths were among people 70 years or younger and the percentage of premature deaths from NCDs ranged from 36.5 to 72.1%. Despite the burden of NCDs, the availability of essential medicines and health services was sub-optimal in public health facilities. The prevalence of key risk factors such as tobacco use, physical inactivity, overweight, and alcohol consumption per capita varied by sex and across the region, with the prevalence of tobacco use and consumption of alcohol higher among men, while the prevalence of insufficient physical activity and overweight higher among women. Public health responses to NCDs remained sub-optimal due to limited national NCD targets, inadequate surveillance, risk factor reduction measures, and access to essential medicines. Though the NCD ASMR has decreased, there has been an increase in NCD-related deaths and the percentage of deaths due to NCDs over the last two decades in the WHO African Region. The mortality burden of NCDs and the prevalence of risk factors remains relatively high, while mounting a public health response for preventing and controlling these NCDs remains challenging. Accelerated action is essential to meet global and regional NCD reduction targets. Strengthening national NCD targets, improving surveillance, ensuring access to essential medicines, and scaling up risk factor reduction strategies are critical to reversing current trends and achieving the 2030 SDG NCD targets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are chronic conditions resulting from a combination of genetic, metabolic, environmental, and behavioural factors1. NCDs are the leading cause of death and disability worldwide2 and a major public health challenge undermining social and economic development3. Furthermore, deaths from NCDs are rising; NCDs accounted for 7 of the top 10 causes of mortality worldwide in 2019, compared to 4 in 20004. Cardiovascular diseases (CVD), diabetes, cancers, and chronic respiratory diseases (CRD), collectively represent over 80% of the global NCD burden5,6.

Although communicable diseases, maternal, childhood and nutritional causes have historically dominated public health priorities in Africa, the burden of NCDs is rapidly increasing. In sub-Saharan Africa, the NCD burden ballooned by 67% between 1990 and 2017, driving an increase from 18 to 30% in the proportion of total disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) attributable to NCDs5.

CVD has emerged as the leading cause of NCD deaths, followed by cancers, diabetes, and CRD in the WHO African region. These four NCDs contribute significantly to deaths with substantial variation across the region7. Further, an estimated 1.6 million people between the ages of 30 and 70 die prematurely each year from one of the major NCDs, representing 63% of all NCD-related deaths8. Cancers, CRD, CVD, and diabetes account for over 70% of premature deaths8.

The burden of NCDs poses a threat to individual health and hampers progress toward achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development1. The rising prevalence of NCDs is predicted to impede poverty reduction initiatives in the WHO African Region, increasing household financial burden from associated healthcare costs1. Vulnerable and socially disadvantaged populations are disproportionately affected by limited availability and access to health services and greater exposure to risk factors, such as tobacco and alcohol use, physical inactivity, and poor or unhealthy diets. These risk factors contribute to elevated blood pressure, obesity, high blood glucose levels, and hyperlipidaemia1.

If current trends continue, the proportional contribution of NCDs to total mortality will exceed communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases combined by 20302,9. As these conditions lead to millions of premature deaths, years lived with disability, and significant economic losses annually, it is imperative to shift attention toward their prevention and management across the WHO African Region.

Effective NCD surveillance is essential for informing policy and guiding interventions. The WHO has developed standardized tools such as the STEPwise approach to NCD risk factor surveillance (STEPS)10, Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS)11, Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS)12, and Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS)13 to support countries in tracking NCD risk factor prevalence and trends14. Civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS) systems are critical for monitoring the mortality and cause-of-death data, which is a challenge in many countries, particularly in the WHO African region15. The WHO supports countries in strengthening CRVS through efforts in medical certification of causes of death and ICD coding and has also developed the SCORE technical package to help improve routine data systems for health, including surveillance and vital statistics16

Building on these efforts to strengthen NCD surveillance and data systems, the WHO developed the Package of Essential Noncommunicable (PEN) Disease Interventions for primary health care to support people with NCDs through universal health coverage. First published in 2010 and updated in 2017 as ‘best buys’ for NCD prevention and control17, these cost-effective interventions include increasing tobacco and alcohol taxes and implementing plain tobacco labels, reformulating products and setting targets for salt in food and meals, promoting physical activity with mass media campaigns and community-based education, motivational, and environmental programmes. These interventions can be adapted to resource-limited settings to address the key risk factors for NCDs (tobacco, harmful use of alcohol, unhealthy diet, and physical inactivity) and select NCDs (CVD, diabetes, cancer, and CRD)17,18.

This study evaluated the NCD epidemic and response measures in the WHO African region by describing and analysing trends in NCD mortality (2000–2019), key behavioural risk factors, availability of essential medicines in public facilities and NCD progress indicators, namely (i) national NCD targets, (ii) mortality data, (iii) risk factor surveys, (iv) national integrated NCD policies, strategies, and/or action plans, (v) and risk factor reduction measures using the most recent available NCD data at the time of the study. Additionally, data on national NCD response efforts, such as the availability of national NCD targets and risk factor reduction measures, were examined. The research findings provide essential information for future health policies and intervention programs to prevent and control NCDs.

Methods

Data sources

Data were obtained from WHO via the NCD data portal (which contains data from the STEPS surveys and NCD country capacity surveys data)8,19 and the Global Health Observatory (GHO)20. Age-standardized mortality data for NCDs (cancer, CRD, CVD, and diabetes) and premature mortality data were obtained from the WHO NCD portal8. Data on risk factors were sourced from the WHO NCD portal and GHO8,20. Data on surveillance were obtained from the WHO NCD Surveillance, Monitoring and Reporting database19. Data on NCD response/progress indicators were from the NCD country capacity survey and WHO NCD portal8,19.

Definition of indicators

NCD outcomes

NCD outcomes were pre-determined based on the WHO NCD Global Monitoring Framework and targets including NCD mortality, four main NCD risk factors (tobacco use, alcohol consumption, physical inactivity and overweight), availability of essential medicines and public health response6,14,15. Mortality rates of the four major NCDs in the WHO NCD framework and the proportion of deaths attributed to NCDs were included. Mortality data from the NCD data portal are from the WHO Global Health Estimates (GHE). Detailed methods are described elsewhere23.

The availability of essential medicines and health services for hypertension, diabetes, and cancer were selected as important first-step indicators representing access. This indicator reflects a key component of the NCD response, as highlighted in multiple UN political declarations and the global action plan for the prevention and control of NCDs3,21,24.

Lastly, 2019 data on NCD response (specifically setting national NCD targets, mortality data, risk factor surveys, risk factor reduction measures, guidelines for management of the four main NCDs, public education and awareness campaigns, and drug therapy to prevent heart attacks and strokes) for the WHO African Region was extracted from WHO country capacity survey data. These elements are the country response/progress monitoring indicators for targets in NCD prevention and management in the region and beyond.

Selected NCD behavioural risk factors

The four major NCD behavioural risk factors specified by the WHO were used: (i) tobacco use, (ii) harmful use of alcohol, (iii) unhealthy diet, and (iv) physical inactivity, defined as:

-

i.

Tobacco use—The percentage of the population aged 15 years and over who currently use any tobacco product (smoked and/or smokeless tobacco) on a daily or non-daily basis. Tobacco products include cigarettes, pipes, cigars, cigarillos, waterpipes (hookah, shisha), bidis, kretek, heated tobacco products, and all forms of smokeless (oral and nasal) tobacco25.

-

ii.

Physical inactivity—Prevalence of insufficient physical activity among adults aged 18 + years (age-standardized estimate) (%) was defined as the percentage of the defined population attaining less than 150 min of moderate-intensity physical activity per week, or less than 75 min of vigorous-intensity physical activity per week, or equivalent26.

-

iii.

Overweight as a proxy for unhealthy diet—Percentage of adults aged 18 + years with a body mass index (BMI) of 25 kg/m2 or higher27.

-

iv.

Alcohol consumption—Total alcohol per capita (15 +) consumption (in litres of pure alcohol) (SDG Indicator 3.5.2) was defined as the total (sum of three-year average recorded and three-year average unrecorded APC, adjusted for three-year average tourist consumption) amount of alcohol consumed per adult (15 + years) over a calendar year, in litres of pure alcohol28.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize NCD mortality rates including CVD, diabetes, cancer, and CRD and selected risk factors data. Data cleaning, analysis and generating the figures and tables were conducted using Microsoft Excel. The changes in mortality rates per 100 000 population between 2000 and 2019 were calculated as both absolute and relative differences in these measures between the two periods. The percentage of NCD deaths was determined by calculating the proportion of NCD-related deaths out of total deaths.

Patient and public involvement

In this study, we used de-identified data from publicly available WHO data repositories. As such, there was no direct engagement with patients or the public in the design, conduct, reporting, or dissemination of this research.

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted using de-identified data from publicly available WHO data repositories. Since the data was already in the public domain and did not involve any new data collection from human or animal subjects, ethical approval was not required.

Results

NCD Mortality trend in the WHO African region

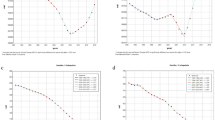

NCD-related deaths increased in the WHO African Region over the last 20 years (Fig. 1, Panel A). In the region, 2 100 840 out of 8 696 864 deaths (24.2%) were caused by NCDs in 2000, compared to 2 889 945 out of 7 786 394 deaths (37.1%) in 2019, resulting in an absolute increase of 12.9% and a relative increase of 53.3% in the proportion of deaths attributed to NCDs over the period. From 2000 to 2019, CVD had the highest absolute increase in estimated deaths, with 261 548 additional deaths, representing a 31.4% rise. Cancer-related deaths also rose sharply, with 211 089 more cases, reflecting a 65.3% increase. Diabetes mellitus deaths increased by 69 875, marking a 48.1% rise, while respiratory diseases had the smallest absolute increase of 24 599 deaths, corresponding to a 15.3% increase. Throughout the years, CVD caused the highest number of deaths among the four main NCDs, followed by cancers (malignant neoplasms), diabetes mellitus, and CRD. In 2019 alone, CVD, cancer, CRD, and diabetes mellitus caused 1 093 577, 534 293, 185 472, and 177 079 deaths, respectively, in the WHO African Region.

Between 2000 and 2019, there was a 21.9% and 18.2% average relative reduction in age-standardized NCD mortality rates globally and in the WHO African Region, respectively. The age standardized NCD mortality rate continuously and steadily decreased over time globally and in the WHO African Region (Fig. 1, Panel B). However, the WHO African Region consistently maintained a higher age-standardized NCD mortality rate than the global rates. Specifically, the global age-standardized NCD mortality rate decreased from 613.3 [470.1–794.3] in 2000 to 478.8 [335.2–667.6] per 100 000 population in 2019, whereas the WHO African region rate decreased from 717.7 [426.2–1157] to 587.1 [342.3–955.4] per 100 000 population during the same period.

There was substantial variation in age-standardized NCD mortality across countries, as shown in Fig. 1, Panel C. Notably, Lesotho (1137.2), Eswatini (917.1), and the Central African Republic (911.1) exhibited the highest NCD mortality rates. By contrast, Algeria (445.8), Mauritania (476.2), and South Sudan (481.1) showed comparatively lower rates. Out of all the included African countries, only Algeria and Mauritania had lower NCD age-standardized mortality rates than the global average. Additionally, there was substantial variation in the proportion of deaths attributed to NCDs across countries (Fig. 1, Panel D), with Mauritius exhibiting the highest percentage at 88.4% and Chad the lowest at 27.0%. Among the 47 countries in the WHO African region, 21 (44.7%) had 40% or more of total deaths attributed to NCDs, and 24 (51.1%) had 30–39.3% of their total deaths attributed to NCDs.

The NCD burden across these countries revealed distinctive patterns in the probability of premature mortality and age-standardized death rates per 100 000 population for cancer, CVD, diabetes, and CRD (Table 1). In 2019, the probability of premature mortality from NCDs was higher in the WHO African Region (21%) compared to the global average (18%). Compared to the global average (42%), in the WHO African Region, 64% of NCD deaths occurred among individuals under the age of 70 years—the highest proportion among all six WHO regions. Lesotho stood out with the highest NCD burden, particularly in the probability of premature mortality (43%) and age-standardized mortality rate per 100 000 population for CVD (491) and CRD (135). The age-standardized mortality rates for cancer (98) and diabetes (169) were also high in Lesotho compared to other countries. Lesotho (43%) Eswatini (35%), Central African Republic (36%), and Mozambique (31%) also displayed elevated probabilities of premature NCD mortality. In contrast, Algeria, Cabo Verde, and Mauritius exhibited a relatively lower NCD mortality burden including premature mortality, and across the four main NCDs.

NCD risk factors

Key risk factors for NCDs across African countries underscore the varied prevalence of tobacco use among people aged 15 +, total alcohol consumption per capita use among people aged 15 +, physical inactivity among adults aged 18 +, and the proportion of adults aged 18 + who are overweight (Table 1). The lowest tobacco use was observed in Ghana (3.6%), followed by Nigeria (3.9%), whereas the highest tobacco use was in Madagascar (28.4%) and Lesotho (24.4%). While countries within the WHO African Region appear to have comparably lower prevalence of tobacco use when compared to the global average and other regions, there were significant disparities at the country level when data were disaggregated by sex (Fig. 2, Panel A). The overall tobacco prevalence in Lesotho, for instance, hides significant sex disparities—with 43.6% of men reporting current tobacco use compared to only 5.1% of women. Similar trends were seen in Madagascar and Algeria, where tobacco use among men was 43.0% and 41.8% respectively in 2022.

Countries with the highest annual alcohol consumption per capita were Uganda (12.2L) and Seychelles (12.0L), while Mauritania and South Sudan (0.0L) had the lowest. Important differences emerge when looking at patterns of alcohol consumption by sex (Fig. 2, Panel B). Overall annual total alcohol consumption in Uganda, for instance, at 12.2L per capita, hides significant differences between men and women, who consume 19.9L and 4.9L, respectively.

Six countries reported physical inactivity in more than 25% of adults aged 18 years and older (Table 1). Mauritania and Mali reported the highest proportion of inactivity (41.3% and 40.4%, respectively), followed by South Africa (38.2%), Algeria (33.6%), Namibia (33.4%), and Côte d’Ivoire (33.1%). Sex differences in levels of physical inactivity were most pronounced in South Africa, where 47.3% of women were reported as being inactive, compared to 28.5% of men (Fig. 2, Panel C). A similar trend was observed in Mali (47.1% of women were physically inactive compared to 33.7% of men).

Five countries reported over 50% of their adult population as being overweight (Table 1). Seychelles reported the highest (60.8%), followed by Algeria (57.6%), Eswatini (57.1%), South Africa (55.0%), and Mauritius (51.1%). The overall overweight prevalence estimates hide significant disparities at the country level, as shown when data are disaggregated by sex (Fig. 2, Panel D). The overall overweight prevalence of 57.1% in Eswatini, for example, hides significant sex disparities—with some 72.6% of women reported as overweight (considerably higher than the global (43.9%) and regional (38.7%) averages for women).

Availability of essential medicines and health services

Figure 3 provides information on the availability of essential medicines and health services related to the medical management of blood pressure, diabetes, and cancer in the WHO African Region. Panel A provides information on the availability of various blood pressure medicines in the WHO African Region. The most commonly available medicine was thiazide diuretics (80.9%), followed by angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (68.1%). The availability of fixed-dose combinations was relatively low compared to other blood pressure medicines. For diabetes management, results indicate varying levels of availability of essential medicines across the WHO African Region (Panel B). Aspirin and metformin were the most widely available (80% of countries); however, 68% reported general availability of insulin and only 50% reported general availability of sulfonylureas. Regarding the availability of cancer services (Panel C), 70.2% and 72.4% of countries reported availability of outpatient and inpatient cancer care. However, only 38% reported availability of radiotherapy services.

NCD risk factor surveillance surveys

Table 2 also highlights the assessment of surveillance for NCD risk factors in African countries. The number of surveys conducted over the past five years shows a diverse landscape. Ghana and Togo emerged as the top countries conducting regular surveys. In the past five years, three NCD-related surveys were conducted in Togo and two were conducted in Ghana. Ghana conducted four Global Youth Tobacco Surveys (GYTS) and Global School-based Student Health Surveys (GSHS), the most recent of which was in 2022. Togo conducted four GYTS and two STEPwise approaches to NCD risk factor surveillance (STEPS) surveys, the most recent of which was in 2021. Only two countries, the United Republic of Tanzania and Botswana, have conducted one Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) in the past five years (since 2017).

NCD progress indicators in the African region

The assessment of the NCD response, represented by: (i) the setting of national NCD targets, (ii) the availability of mortality data, (iii) the conduct of NCD risk factor surveys, (iv) national integrated NCD policies, strategies, and/or action plans, (v) and risk factor reduction measures to reduce tobacco use, alcohol consumption and unhealthy diets revealed varied progress across African countries (Table 3). Twenty-eight countries (59.6%) achieved setting national NCD targets; however, 43 (91.5%) did not have a functioning system, such as a CRVS which reports data to the WHO databases, to generate reliable cause-specific mortality data on a routine basis. Only Mauritius, Seychelles, and South Africa had a fully functional system for recording mortality. Twenty-two countries (46.8%) had an operational multisectoral national strategy/action plan that integrates the major NCDs and their shared risk factors. Furthermore, none (0/47) of the countries in the region had fully achieved the implementation of a STEPS survey or another risk factor survey that included physical measurements and biochemical assessments covering key behavioural and metabolic risk factors for NCDs at least every five years.

Implementation of tobacco demand-reduction and harmful alcohol use reduction measures in the WHO African Region was inconsistent. Tobacco control efforts varied, with only 4.3% of countries fully implementing increased excise taxes, while 46.8% had bans on tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship. Graphic health warnings were fully implemented in 29.8% of countries, while smoke-free policies were achieved in 23.4%. However, 66.0% of countries had no mass media campaigns on tobacco harm. Alcohol control measures also showed gaps, with only 14.9% fully restricting availability and advertising exposure, while 68.1% partially restricted alcohol availability. Excise tax increases on alcohol were fully implemented in 25.5% of countries, while 34.0% had no such measures. Among the NCD risk factor reduction measures, unhealthy diet measures were the least implemented. None of the WHO African Region countries had fully implemented national policies to reduce population salt/sodium consumption and policies limiting saturated fatty acids and eliminating trans-fatty acids. Only two countries, Seychelles and South Africa, implemented the policy(ies) to reduce the impact on children of marketing of foods and non-alcoholic beverages high in saturated fats, trans-fatty acids, free sugars, or salt based on the WHO set of recommendations.

The implementation of public education and awareness campaigns on physical activity, guidelines for NCD management, and drug therapy/counselling to prevent heart attacks and strokes was suboptimal across the WHO African Region. Only five countries (10.6%) had fully implemented public education and awareness campaigns on physical activity, while the majority (38 countries, 80.9%) had not achieved this indicator. Similarly, only two countries (4.3%, Rwanda and Cabo Verde) had fully implemented the provision of drug therapy, including glycaemic control, and counselling for eligible persons at high risk to prevent heart attacks and strokes, with emphasis on the primary care level, with 80.9% of countries failing to achieve this measure. Guidelines for the management of cancer, CVD, diabetes, and CRD were more widely adopted, with 19 countries (40.4%) fully implementing them and 13 (27.7%) achieving partial implementation. However, 15 countries (31.9%) had not adopted NCD guidelines for the four main NCDs.

Discussion

NCD mortality trends and premature mortality

More than 2.8 million NCD-related deaths were recorded in the WHO African Region in 2019. Importantly, while the total number of deaths in the region has fallen over the last two decades, deaths due to NCDs have increased. Between 2000 and 2019, the proportion of overall deaths due to NCDs in the WHO African region increased from 24.2 to 37.1%, largely due to weaknesses in the implementation of NCD prevention, diagnosis, and care as well as the burden of key risk factors such as tobacco use, unhealthy diets, physical inactivity, and harmful use of alcohol.

Meanwhile, age-standardized NCD mortality rate has continuously and steadily declined in the WHO African Region between 2000 and 2019, with an 18.2% reduction compared to a 21.9% global decrease. Age-standardized NCD mortality rate in the region has consistently remained higher than the global average over the past 20 years, indicating persistent inequalities in health outcomes. These disparities are further exacerbated by poverty, which limits access to prevention, diagnosis, and treatment, contributing to worse NCD outcomes, particularly among marginalized populations30.

Substantial variations in overall NCD mortality rates and the mortality rates of CVD, diabetes, cancer and CRD across countries underscore the diverse NCD epidemiological profiles in the WHO African Region. Given these differences, a one-size-fits-all approach may not be effective, and context-specific interventions are essential to address country-specific health challenges. The extremely high mortality rates in Lesotho, the Central African Republic, and Eswatini likely reflect a combination of high-risk factor prevalence and inadequate health system responses and limited availability of essential NCD medicines. In Lesotho, the exceptionally high tobacco use among men (43.6%) and the high prevalence of overweight among women (58%) may be key contributors to the burden, compounded by the country’s limited achievement of NCD response indicators, with only one indicator fully achieved. Eswatini also demonstrates concerning risk factor patterns, including high alcohol consumption among men (13.7L, significantly above the regional average of 7.5L) and the highest prevalence of overweight among women in the region (over 70%). Although Central African Republic has lower reported levels of alcohol consumption and overweight prevalence, its weak health system response—with only two NCD indicators partially achieved and 13 not achieved—suggests a significant gap in prevention and care.

The WHO African Region had a higher probability of premature NCD mortality (21%) than the global average (18%), with 64% of NCD deaths occurring under age 70—well above the global average of 42% and the highest among all WHO regions. This could be a result of differences in availability and access to essential medicines and health services or quality of the services provided likely resulting in late diagnoses leading to poorer health outcomes such as death. According to a recent systematic review, the lack of medical care, and low health budgets are among the factors responsible for the increasing NCD burden in Africa 31. Substantial variation in premature mortality due to NCDs in the region underscores the need for tailored public health strategies to reduce premature mortality through increased availability and access to essential health services, as well as improved health system responses. Furthermore, the double burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases in the WHO African Region further complicates the allocation of resources, straining already limited funding for essential medicines and health services, and exacerbating challenges in NCD prevention and care. Fortunately, a promising approach to addressing these challenges is the integration of NCD care into well-established and successful disease programmes, such as HIV/AIDS initiatives, which have proven effective in delivering comprehensive healthcare and improving health outcomes across sub-Saharan Africa.

NCD risk factors: prevalence and disparities

Key risk factors for NCDs across African countries underscore the varied prevalence of tobacco use and alcohol consumption among people aged 15 +, physical inactivity among adults aged 18 +, and the proportion of adults aged 18 + who are overweight. Dalal et al., also reported that the prevalence of NCD risk factors varied considerably between countries, urban/rural location and other sub-populations32. The disparities in our findings emphasize the need for targeted public health interventions addressing specific risk factors at national and sub-national levels to mitigate the growing burden of NCDs. For instance, a study in Sudan found that while communities had adequate knowledge of tobacco use, healthy diets, and physical activity, their lifestyle practices did not align with this knowledge. This highlights the need for behavioural interventions to bridge the gap between awareness and practice. Considering the diversity in lifestyle patterns and behaviours across the African continent, interventions should be context-specific to effectively address these disparities.

Similar to other studies, the prevalence of tobacco use, physical activity, overweight, and alcohol consumption exhibited disparities between men and women33,34,35,36. Tobacco use was higher among men, and men also consumed more alcohol. Women, on the other hand, were more likely to be physically inactive and overweight. This can be attributed to a complex interplay of sociocultural, economic, and biological factors. In the case of men and tobacco use, studies suggest complex sociocultural and biological mechanisms for the increased use of tobacco among men. Tobacco is often associated with “masculinity”, marketed so by tobacco companies—a sociocultural element that increases use among men, additionally, biological factors such as the nicotine metabolite ratio (NMR), may affect sexes differently, with one study correlating NMR with increased tobacco use in men, but not in women. Similarly, studies on alcohol use and sex differences suggest men are more likely to consume alcohol compared to women to showcase economic power, be socially accepted, and as a coping mechanism36,37. These disparities highlight the need for targeted interventions and sex-sensitive health policies to effectively address the risk factors contributing to NCDs.

Availability of essential medicines and NCD services

The availability of essential medicines and health services remained suboptimal, highlighting gaps in treatment and NCD management. However, availability alone does not address access-related barriers, such as geographical proximity, affordability, and cultural considerations, which are crucial for effective healthcare utilization. At the country level, the WHO PEN is a well-established, cost-effective, and action-oriented strategy with recommended interventions that can be implemented and scaled up to national levels to provide geographically accessible care at community health centres to treat common NCDs in an integrated outpatient package18. In 2019, only Benin, Eritrea, South Africa and Togo reported having a nationally integrated package of interventions. An additional eight countries had partially implemented the WHO package into their national health system38,39. However, overall implementation remains low considering the regional burden of NCDs. In addition to PEN, WHO is developing the NCD Implementation Roadmap 2023–2030 in response to the Global Action Plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013–2020 to guide countries in strengthening NCD prevention and control through multisectoral policies, health system strengthening, and risk factor reduction. This roadmap complements existing frameworks, including the WHO "Best Buys," by providing practical actions for governments to accelerate progress toward NCD targets at both the prevention and treatment levels.

Progress indicators: NCD targets

Progress in addressing NCDs in the WHO African Region remained limited. Despite the burden of NCDs in the WHO African Region, only 28 out of 47 countries (59.6%) had established time-bound targets. The absence of such targets in 19 countries may hinder progress in reducing NCD-related morbidity and mortality, as clear benchmarks are essential for tracking and driving action. Surveillance capacity was also inadequate, as no country had fully implemented a STEPS or equivalent risk factor survey incorporating physical and biochemical measurements at least once every five years, highlighting critical gaps in data collection and evidence-based policymaking.

Progress indicators: risk factor reduction measures—tobacco, alcohol, unhealthy diets and physical inactivity

Tobacco control measures varied across the region. While some countries had implemented smoke-free policies, advertising restrictions, and media campaigns, enforcement remained inconsistent. Only Madagascar and Mauritius (4.3%) had fully implemented measures to reduce tobacco affordability through excise taxation. Strengthening tobacco control policies and enforcement mechanisms remains essential, particularly given the high prevalence of tobacco use among men.

Alcohol reduction measures showed even lower levels of achievement compared to tobacco reduction measures, with most countries failing to effectively regulate alcohol availability, taxation, and marketing, despite the well-documented association between the harmful use of alcohol and NCDs.

Similarly, the countries in the region also lagged in implementing nutrition-related policies, with many countries failing to enforce front-of-pack labelling, food procurement regulations, marketing restrictions on unhealthy foods targeted at children, and national dietary campaigns. These gaps contribute to the rising prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and CVD, highlighting the need for stronger interventions to promote healthier diets. The promotion of breastfeeding and regulation of breastmilk substitutes was also weak in many countries, despite its known benefits in preventing childhood malnutrition and later-life NCD risks. Among the major risk factor reduction strategies, measures targeting unhealthy diets exhibited the lowest level of implementation.

The promotion of physical activity remains a key challenge in the WHO African Region, with only 5 out of 47 countries (10.6%) fully achieving at least one recent national public awareness programme or motivational communication campaign for physical activity, including mass media initiatives aimed at behavioural change. Given the increasing burden of obesity and sedentary lifestyles, prioritizing policies and interventions that promote physical activity is essential.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is the first study to provide comprehensive and updated NCD trends in 47 countries in the WHO African Region based on mortality rates, the four main modifiable risk factors, and national public health responses. The study contributes to the scientific evidence base generated on the African continent, providing valuable insights into the disparities in NCDs burden in the region and the need for targeted public health interventions. In addition, we have documented a list of evidence-based, actionable recommendations for countries to consider implementing to strengthen NCD prevention and control efforts.

However, there are several limitations to consider when interpreting these findings. Some of the data used were global estimates from multiple sources, including global and regional data repositories. This reliance on varying data sources with different collection, reporting, and surveillance systems across countries affects data accuracy. Only a few countries in the WHO African region have a CRVS system with complete coverage and medical certification of cause of death, and robust data systems for NCD leading to potential underestimations of NCD mortality rates. Incomplete data, along with inconsistencies between data sources, further complicate interpretation. Variability in survey frequency across countries also impacts representativeness. Additionally, ecological bias is a key limitation, as the data are drawn from national-level surveys across multiple countries, which may not fully capture subnational variations in NCD burden and risk factors. Furthermore, some surveys rely on self-reported data, particularly for sensitive topics such as tobacco and alcohol use or health system response, introducing potential omission biases due to underreporting or social desirability bias. These limitations underscore the need for improved data harmonization and strengthening of reporting mechanisms to enhance the accuracy and reliability of NCD trends in the region. Despite these limitations, the most recent available data were used, and the data are based on estimates from surveys conducted in the countries included in this study.

Recommendations

To address the escalating burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in the WHO African Region, urgent and coordinated actions are required. The following key recommendations are proposed:

Target high-risk populations with tailored interventions

-

Regional Focus on Young Adults: With 64% of NCD deaths occurring among individuals under 70, primary prevention programmes should be tailored to younger populations. These initiatives should emphasize early detection and management, lifestyle modification, and risk factor reduction to curb the onset of NCDs in adulthood.

-

Gender-Specific Strategies: Address the pronounced gender differences in risk factor prevalence (e.g., tobacco use in men and physical inactivity in women) by developing gender-tailored health promotion campaigns. For example, in Lesotho, implement smoking cessation programmes targeted at men, while in South Africa, design physical activity programmes that appeal specifically to women.

Strengthen national NCD targets and accelerate policy implementation

-

Set and Monitor National Targets: All countries in the WHO African Region should institutionalize national NCD targets, beyond the current 59.6% adoption, and establish structured review mechanisms to track progress and policy effectiveness.

Improve surveillance and data systems

-

Strengthen civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS) Systems: Given that 91.5% of countries lack reliable cause-specific mortality data, prioritizing CRVS system enhancements will provide accurate epidemiological insights and inform policy interventions.

-

Expand Use of WHO-Recommended Surveillance Tools: Countries should implement standardized surveillance mechanisms, such as the STEPS survey, to improve data availability, track risk factor prevalence, and facilitate evidence-based decision-making.

-

Enhance Monitoring and Reporting Mechanisms: Establishing comprehensive tracking systems for NCD response efforts will promote accountability, ensure data-driven policymaking, and enable systematic progress evaluations.

Improve access to essential medicines and services

-

Strengthen Supply Chains: Addressing inconsistencies in the availability of essential NCD medicines (e.g., only 50% availability for sulfonylureas) requires centralized procurement systems to ensure continuous access to life-saving medications, including thiazide diuretics and anti-diabetic drugs, within public health facilities.

-

Invest in Infrastructure for Advanced Therapies: With only 38% of countries having access to radiotherapy services, governments should prioritize oncology infrastructure development through regional centres of excellence and public–private partnerships to expand treatment accessibility.

Scale up risk factor reduction measures

Implement Stronger Legislative and Policy Interventions: Addressing key NCD risk factors requires stringent regulations on tobacco and alcohol control, enhanced physical activity promotion, improved nutrition policies, and strict food marketing regulations.

-

Expand Public Awareness Campaigns: Behavioural change communication strategies should be intensified to educate communities on healthy lifestyle choices, fostering long-term reductions in NCD incidence across the region.

By implementing these strategic recommendations, countries in the WHO African Region can strengthen their NCD response, mitigate premature mortality, and work towards achieving global health targets for sustainable disease prevention and control.

Conclusion

The findings from this study reflect a complex landscape of NCDs in the WHO African Region. While there has been an increase in NCD-related deaths and the percentage of deaths due to NCDs over the last two decades, particularly from CVD and cancer, there is a promising trend of decreasing age-standardized mortality rates. However, the age-standardized NCD mortality rate remains consistently higher than the global average, indicating persistent inequalities in NCD mortality outcomes. Furthermore, the proportion of premature deaths from NCDs is the highest in Africa when compared to all WHO Regions. The country-specific NCD mortality burden varies significantly, and the prevalence of key risk factors varied, particularly when disaggregated by sex, underscores the need for targeted, cost-effective, and context-specific interventions. Despite the high mortality burden and prevalence of NCDs, the surveillance, healthcare infrastructure, and availability of essential medicines and health services remain sub-optimal and regionally varied. The widespread prevalence of NCD risk factors, combined with limited financing for prevention and control, further exacerbates these challenges, highlighting the need for cost-effective and evidence-based interventions. Overall, these findings underscore the urgent need for region-, sub-region-, country-, and sex-specific approaches, like the WHO-recommended and cost-effective PEN recommendations, advocating for a comprehensive, people-centred, and integrated response to the NCD epidemic in the WHO African region to achieve the 2030 global targets.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

References

WHO Regional Office for Africa. Communicable and Non-Communicable Diseases in Africa in 2021/22. 2023. https://www.afro.who.int/publications/communicable-and-non-communicable-diseases-africa-202122. Date accessed: November 07, (2023).

World Health Organization African Region. Noncommunicable Diseases - Key Facts. In: https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/noncommunicable-diseases#:~:text=These%20five%20main%20NCDs%20are,inactivity%20and%20eating%20unhealthy%20diets. Date accessed: November 07, (2023).

World Health Organization. Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases, 2013–2020. (2013).

World Health Organization. Global health estimates: Leading causes of death - Cause-specific mortality, 2000–2019. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-leading-causes-of-death. Date accessed: November 09, (2023).

Gouda, H. N. et al. Burden of non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, 1990–2017: Results from the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Glob Health. 7, e1375–e1387. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30374-2 (2019).

World Health Organization. NCD global monitoring framework. . Geneva; (2011).

World Health Organization - African Region. Deaths from noncommunicable diseases on the rise in Africa. In: https://www.afro.who.int/news/deaths-noncommunicable-diseases-rise-africa. 2022. Date accessed: November 07, (2023).

World Health Organization. NCD Data Portal. https://ncdportal.org/. Date accessed: December 04, (2023).

Africa CDC. Non communicable diseases, injuries prevention and control and mental health promotion strategy (2022–26). (2022).

World Health Organization. STEPwise approach to NCD risk factor surveillance (STEPS). https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/surveillance/systems-tools/steps. Date accessed: December 05, (2023).

World Health Organization. Global school-based student health survey. https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/surveillance/systems-tools/global-school-based-student-health-survey. Date accessed: December 05, (2023).

World Health Organization. Global Adult Tobacco Survey. https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/surveillance/systems-tools/global-adult-tobacco-survey. Date accessed: December 05, (2023).

World Health Organization. Global Youth Tobacco Survey. https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/surveillance/systems-tools/global-youth-tobacco-survey. Date accessed: December 05, (2023).

World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Disease Surveillance, Monitoring and Reporting. https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/surveillance/systems-tools. Date accessed: December 05, (2023).

World Health Organization. Civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS). https://www.who.int/data/data-collection-tools/civil-registration-and-vital-statistics-(crvs). Date accessed: March 15, (2025).

World Health Organization. SCORE for Health Data Technical Package. https://www.who.int/data/data-collection-tools/score. Date accessed: March 15, (2025).

World Health Organization. ‘Best buys’ and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases - Tackling NCDs. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/259232/WHO-NMH-NVI-17.9-eng.pdf?isAllowed=y&sequence=1. Date: 2017. Date accessed: November 07, (2023)

World Health Organization. WHO Package of Essential Noncommunicable (PEN) Disease Interventions for Primary Healthcare. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240009226. Date: 2020. Date accessed: November 01, (2023).

World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Disease Surveillance, Monitoring and Reporting - NCD country capacity survey. https://www.who.int/teams/ncds/surveillance/monitoring-capacity/ncdccs. Date accessed: May 20, (2024).

World Health Organization. The Global Health Observatory. https://www.who.int/data/gho. Date accessed: December 11, (2023).

United Nations General Assembly. Political declaration of the high-level meeting of the General Assembly on the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/710899/?ln=en. Date: 2011. Date accessed: November 01, (2023).

World Health Organization - Regional Office for Africa. The Brazzaville Declaration on Noncommunicable Diseases Prevention and Control in the WHO African Region. https://www.iccp-portal.org/system/files/resources/ncds-brazzaville-declaration20110411.pdf Date: 2011. Date accessed: November 01, (2023).

World Health Organization. WHO methods and data sources for country-level causes of death 2000–2019. Global Health Estimates Technical Paper WHO/DDI/DNA/GHE/2020.2; (2020).

United Nations General Assembly. Political Declaration of the High-level Meeting on Universal Health Coverage “Universal health coverage: moving together to build a healthier world”. (2019).

Bilano, V. et al. Global trends and projections for tobacco use, 1990–2025: An analysis of smoking indicators from the WHO comprehensive information systems for tobacco control. The Lancet. 385, 966–976. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60264-1 (2015).

Guthold, R., Stevens, G. A., Riley, L. M. & Bull, F. C. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1·9 million participants. Lancet Glob Health. 6, e1077–e1086. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30357-7 (2018).

Phelps, N. H. et al. Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. The Lancet 403, 1027–1050. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02750-2 (2024).

World Health Organization. The Global Health Observatory. Alcohol, total per capita (15+) consumption. https://www.who.int/data/gho/indicator-metadata-registry/imr-details/4759. Date accessed: November 11, (2023).

World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases: progress monitor 2022. 2022. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/353048. Date accessed: March 18, (2025).

Bukhman, G. et al. The Lancet NCDI Poverty Commission: bridging a gap in universal health coverage for the poorest billion. The Lancet 396, 991–1044. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31907-3 (2020).

Bhuiyan, M. A., Galdes, N., Cuschieri, S. & Hu, P. A comparative systematic review of risk factors, prevalence, and challenges contributing to non-communicable diseases in South Asia, Africa, and Caribbeans. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 43, 140. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-024-00607-2 (2024).

Dalal, S. et al. Non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: what we know now. Int. J. Epidemiol. 40, 885–901. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyr050 (2011).

Ackah, M., Owiredu, D., Salifu, M. G. & Yeboah, C. O. Estimated prevalence and gender disparity of physical activity among 64,127 in-school adolescents (aged 12–17 years): A multi-country analysis of Global School-based Health Surveys from 23 African countries. PLOS Global Public Health. 2, e0001016. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001016 (2022).

Sreeramareddy, C. T. & Acharya, K. Trends in prevalence of tobacco use by sex and socioeconomic status in 22 Sub-Saharan African Countries, 2003–2019. JAMA Netw. Open. 4, e2137820. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.37820 (2021).

Agyemang, K., Pokhrel, S., Victor, C. Anokye, N.K. Determinants of obesity in West Africa: A systematic review. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.27.21255462

Belete, H. et al. Alcohol use and alcohol use disorders in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction 119, 1527–1540. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.16514 (2024).

Breuer, C. et al. “The Bottle Is My Wife”: Exploring reasons why men drink alcohol in ugandan fishing communities. Soc. Work Public Health. 34, 657–672. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2019.1666072 (2019).

Tesema, A. et al. Addressing barriers to primary health-care services for noncommunicable diseases in the African Region. Bull. World Health Organ. 98, 906–908. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.20.271239 (2020).

World Health Organization - Regional Office for Africa. The Work of the World Health Organization in the African Region. 2020. https://www.afro.who.int/publications/work-world-health-organization-african-region-report-regional-director. Date accessed: May 05, (2024)

Funding

No funding was provided for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conceptualisation: AB, AC, BI, BF, and CW. Data curation: AB. Formal analysis: AB and NC. Investigation: AB, AC, BI, BF, CW, CBD, KA, NC and PB. Methodology: AB, AC, BI, BF, and CW. Designed figures and tables: AB, CW and NC. Writing original draft of the manuscript: AB. Review and editing the manuscript: AB, AC, BI, BF, CW, CBD, KA, NC, and PB. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript, had full access to all the data, and are responsible for the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Barry, A., Impouma, B., Wolfe, C.M. et al. Non-communicable diseases in the WHO African region: analysis of risk factors, mortality, and responses based on WHO data. Sci Rep 15, 12288 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97180-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97180-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Intervention to optimise body mass index in adolescents and address the triple burden of malnutrition—the Ntshembo (Hope) trial in rural and urban South Africa study: a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial

Trials (2026)

-

Prevalence and determinants of insulin resistance among middle-aged adults in rural northern Ghana: an Awi-Gen cross-sectional study

BMC Public Health (2025)

-

Determinants of non-adherence to medications among hypertensive patients attending the Babcock university teaching hospital clinic in Ilishan-Remo, Ogun state, Nigeria

Discover Public Health (2025)

-

Africa finally has its own drug-regulation agency — and it could transform the continent’s health

Nature (2025)

-

L’Afrique dispose enfin de sa propre agence de réglementation des médicaments, qui pourrait transformer la santé sur le continent

Nature Africa (2025)