Abstract

This scoping review examines how telemedicine addresses healthcare needs in the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual, and other sexual and gender minority (LGBTQIA+) community, focusing on gender-affirming care, mental health, and testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). A literature search of MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, and Scopus was conducted to identify studies published until March 2024 focusing on telemedicine services for LGBTQIA + individuals. Data extraction captured study characteristics, telemedicine applications, and patient and provider satisfaction, and was synthesized to map current knowledge and identify gaps. Thirty-eight studies, comprising observational studies and one randomized controlled trial, were included, encompassing 21,774 participants. Telemedicine facilitated access to gender-affirming care, reduced mental health disparities, and supported HIV and STI testing, with high satisfaction reported among patients and providers. It was particularly effective in reducing appointment no-show rates, enabling remote initiation of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV, and offering mental health support through virtual counseling. The studies also highlighted increased telemedicine adoption for follow-up visits and medication management. However, challenges like digital privacy concerns, technological accessibility, and cultural competence were identified. Telemedicine holds significant potential to improve healthcare access and outcomes for LGBTQIA + populations, particularly in rural and underserved areas. Future efforts should focus on enhancing provider training, ensuring digital equity, and developing culturally competent telehealth models to fully realize these benefits. The findings can inform the design of inclusive telemedicine policies and services tailored to the needs of LGBTQIA + individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual, and other sexual and gender minority (LGBTQIA+) community is characterized by a range of identities, with specific healthcare needs and challenges1. Within the LGBTQIA + community, each group faces unique challenges that require tailored healthcare approaches. For example, gay men have higher rates of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), requiring tailored prevention2. In 2020, CDC data showed that HIV diagnosis rates were highest among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM)2. Thus, specialized services, like pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV, are essential3. Lesbian women face unique health issues, such as reproductive and mental health disparities, but are often under-screened3. Bisexual individuals also face distinct stigmas and health risks, resulting in higher rates of mental health challenges and substance abuse4.Transgender and gender nonconforming individuals face significant barriers to care, including prejudice, a lack of skilled providers, and limited access to gender-affirming treatments5. Research indicates that over half of transgender individuals experience significant mental health challenges, with 51.4% of transgender women and 48.3% of transgender men reporting depressive symptoms and 40.4% of transgender women and 47.5% of transgender men experiencing anxiety5. Additionally, queer individuals may grapple with fluidity in their identities and related healthcare needs that are not always addressed in traditional healthcare settings6. Lack of provider education and cultural competence contributes to healthcare inequalities, worsening disparities and outcomes for LGBTQIA + subgroups7.

Access disparities are especially evident in essential healthcare services; for example, HIV prevention methods like PrEP remain inaccessible for many LGBTQIA + individuals, leading to higher HIV rates. Stigma related to gender identity, expression, socioeconomic status, race, and ethnicity further marginalizes LGBTQIA + individuals, delaying necessary care—particularly for transgender and gender-diverse individuals, who often avoid seeking care due to fear of discrimination8. In response to these challenges, telemedicine has emerged as a promising solution to bridge the gap in access to healthcare for LGBTQIA + populations9.

Telemedicine and mobile health (mHealth) technologies allow individuals to access healthcare remotely, overcoming barriers like transportation, distance, and financial limitations. Digital health tools, including health information technology (HIT), also support clinical decisions, enhance healthcare delivery, improve provider education, and build social support networks for LGBTQIA + individuals8,10. By providing LGBTQIA + affirming care through remote consultations, telemedicine can ensure that individuals who may be hesitant to seek in-person care because of concerns surrounding stigma or confidentiality can still access critical services11. Furthermore, telemedicine has proven effective in improving medication adherence and promoting engagement in care among LGBTQIA + individuals, leading to improved overall health outcomes12,13.

Remote healthcare delivery continues to be important in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the role of telemedicine in addressing healthcare disparities within the LGBTQIA + community has become increasingly prominent13,14,15. Leveraging telemedicine to offer culturally competent, inclusive care can help reduce disparities and improve health outcomes for LGBTQIA + individuals. This review explores the current use of telemedicine in LGBTQIA + healthcare, identifying gaps, best practices, and strategies to enhance access to inclusive, culturally competent care across diverse identities.

Materials and methods

Literature search strategy

This scoping review was conducted according to the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR.)16. A systematic literature search was conducted in MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, and Scopus to explore studies on telemedicine use in healthcare delivery for the LGBTQIA + community. These databases were selected for their comprehensive indexing of global literature and inclusion of rigorously peer-reviewed articles. Additionally, data from grey literature were not included due to the difficulty in assessing study quality, lack of peer review, and potential biases associated with such sources. Search terms and strategies are detailed in the supplementary file. Studies were included from inception until August, 2024.

Study eligibility and selection criteria

Studies focusing primarily on telemedicine use by individuals identifying as members of the LGBTQIA + community were included. Excluded were editorials, commentaries, case reports, case series, reviews, and meta-analyses.

Handling diverse definitions of LGBTQIA + Populations

To address variability in definitions of LGBTQIA + populations, we applied an inclusive approach to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. We accepted studies using terms like “genderqueer,” “non-binary,” “gender nonconforming,” and other identities within the broader LGBTQIA + spectrum. For studies with unique or less common definitions, alignment with our criteria for sexual and gender minorities was assessed. Discrepancies were resolved using a flexible, inclusive framework recognizing identities within LGBTQIA + discourse. For example, overlapping terms like “genderqueer” and “non-binary” were included under a gender-diverse umbrella to ensure comprehensive representation.

Study selection and data extraction

Two investigators (A.G. and H.Q.A.) independently screened titles and abstracts, removing duplicates and ineligible studies. Full-text articles were reviewed to extract data into a pre-piloted Excel sheet, capturing author, year, study design, follow-up period, patient count, characteristics, and outcomes. Articles were categorized into four topics: (1) Telemedicine utilization for gender-affirming care (GAC), (2) HIV and STI-related telemedicine interventions, (3) Transgender health education for providers, and (4) Patient and provider satisfaction. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. No restrictions were placed on sample size or follow-up duration.

Study endpoints and qualitative synthesis

The review aimed to map telemedicine’s role in LGBTQIA + healthcare, identifying key themes, gaps, and areas for future research. It focused on telemedicine utilization, patient attitudes toward GAC, mental health impacts, and its role in HIV and STI testing, including result reporting and therapy monitoring. Additionally, patient and provider satisfaction and the potential for training providers and facilitating interdisciplinary consultations were evaluated. A qualitative synthesis was conducted to summarize findings, highlighting key insights and challenges.

Ethics statement

This scoping review did not require ethical approval since it did not involve human or animal subjects. All data was obtained from previously published sources.

Results

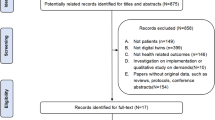

Initially, our comprehensive electronic search yielded 4026 research items. After removal of 436 duplicates, screening of the titles and abstracts of 3459 studies based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria was performed. Out of these, 3357 studies were found to not meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded. Subsequently, we conducted full-text screening on 102 research articles. Ultimately, 38 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final review (Fig. 1)12,13,14,15,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50.

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the included studies in our scoping review encompass a variety of methodologies and areas of focus within the realm of telehealth-administered LGBTQ + care. After the thorough screening process, we incorporated 38 studies into our analysis, consisting of 37 observational studies and one randomized controlled trial12,13,14,15,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50. These studies encompassed a total of 21,774 participants, including both patients and healthcare providers. Detailed baseline characteristics of the included studies can be found in Table 1.

Study endpoints

Telemedicine for Gender-affirming care

Characteristics of studies reporting gender-affirming care

Of the 38 studies, 24 examined GAC, including gender-affirming hormone therapy and surgery consultations pre- and during the COVID-19 pandemic12,13,14,15,17,18,19,20,21,22,25,26,27,31,32,33,34,35,36,40,41,42,46,47. Most studies focused on transgender individuals, gender-diverse youth, and non-binary (NB) individuals, covering both urban and rural populations. Four studies addressed MSM23,28,37,38 one compared heterosexual and sexual minority populations18 and four focused on transgender veterans40,41,42,43. Ten studies17,18,21,22,25,27,29,31,36,39 examined mental well-being, with one studying the impact of delayed hormone therapy and surgery17. Data collection methods varied, including surveys, interviews, and analysis of electronic health records.

Results on gender-affirming care

These studies indicated positive shifts in attitudes toward telemedicine among patients with increased utilization due to the pandemic. Furthermore, they reported overall satisfaction with the use of telemedicine services. Telemedicine was reported as a vital means to help overcome barriers to care, such as transportation, and it was supported by both patients and their families47.

One study reported increased completion rates with fewer cancellations and no-show rates noted in rural settings, indicating improved access and utilization of care when these services were available, especially during the pandemic, when there were limitations imposed on transportation and travel21. Telemedicine was particularly favored for services such as hormone refills and laboratory result monitoring46, credited to reduced transportation barriers and the distance from facilities equipped to provide GAC. Similar trends were observed among patients requiring chronic healthcare, with many preferring telemedicine consultations over in-person visits. This preference was driven by several factors, including convenience, reduced exposure to stigma, lower travel-related costs, and fewer access-related barriers. Additionally, one study also reported an increase in new patient visits, almost half of which were conducted through telemedicine13.

Impact of telemedicine on mental health

Several studies explored the effects of telemedicine on mental health among the LGBTQIA + community17,18,21,22,25,27,29,31,36,39. The studies revealed that delays in gender-affirming hormone therapy and surgeries due to the pandemic led to increased strain and negative mental health effects17,25,27. Access to endocrinologic-gynecologic telemedicine services appeared to mitigate these effects17, with data reporting reduced rates of depression and suicidal ideation, as well as improved mental health scores. Additionally, members of the LGBTQ + community were more likely to utilize telemedicine services and discuss mental and behavioral health concerns during visits compared to their heterosexual counterparts18. Moreover, youth found telemedicine visits to be less stressful, suggesting a positive impact on mental well-being36.

Telemedicine for STI and HIV testing

Numerous studies examined telemedicine’s impact on HIV/STI testing, delivery of HIV results, counseling, PrEP initiation, follow-up rates, and PrEP compliance12,20,23,24,28,30,37,38,44,45,48,49. Participants included transgender youth, gender-diverse youth, MSM, transgender women, and transgender youth of color. One study noted increased telemedicine utilization for HIV counseling and testing during the later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic20. There were no significant differences in reporting HIV-positive results between in-person and telemedicine settings. Intravenous drug users with HIV-positive results preferred telemedicine, as did transgender youth with no prior HIV testing experience20.

Similarly, another study involving MSM found that those with a history of STI positivity, living far from clinics, or with over three sexual partners preferred telemedicine23. Another study highlighted online visits as having the highest number of first-time HIV testers, and individuals with more than two past positive HIV tests favored telemedicine counseling37.

A separate study found no difference between telemedicine and standard users regarding the proportion of PrEP prescriptions, first follow-up attendance, and one-month HIV treatment adherence49. A COVID-19-era study reported decreased no-show rates for online visits, facilitated remote HIV care for a homeless shelter, and successfully initiated PrEP for HIV12.

Patient and provider satisfaction levels

Seventeen studies assessed patient and caregiver satisfaction with telemedicine services13,14,19,20,23,29,30,34,35,39,40,41,42,43,46,47,48. Both medical and behavioral health consultations reported high satisfaction, with attitudes improving notably post-COVID-19, especially for chronic disease management. Video consultations were favored for follow-ups, with many patients preferring them over in-person visits20. Time concerns were minimal, and video visit quality and safety were consistently high19. Preferences varied based on whether the patients had acute or chronic conditions, age (20–50 years), cultural identities, anxiety levels, and parental support. Some participants raised concerns about misgendering in virtual settings34. For monitoring gender-affirming hormone therapy, teleconsultations were as effective as in-person visits but not ideal for initial consultations or surgeries13. Telemedicine positively impacted mental health when in-person care was limited. Patients appreciated psychological, speech therapy, and endocrinological support, showing willingness to continue. While most patients managed virtual visits, some struggled with relationship-building dynamics due to focus issues, technology access, or lack of private space47.

Trans-youth often requested disabling their cameras to manage dysphoria, preferring in-person visits for safety and confidentiality47. Some sought the presence of other providers like nurses or social workers47. Teleconsultation for HIV results was generally satisfactory, though many preferred result submission via a portal over calls48. Male couples valued pre- and post-testing video counseling for STIs, which enabled comprehensive sexual health discussions23. Participants in virtual focus groups for HIV prevention among Black sexual minority men were also satisfied with the format30.

Utilization of telemedicine for Training and Interdisciplinary Consultation Services:

Four studies employed telemedicine services for interdisciplinary consultation and training services aimed at enhancing the quality of care40,41,42,43 Interdisciplinary telemedicine consultations have emerged as a valuable approach to providing comprehensive care to transgender individuals. Such consultations can significantly improve team functioning and boost healthcare providers’ confidence in treating transgender patients.

In a 7-month program involving five interdisciplinary clinical teams41, participants reported that the teleconsultation program was highly beneficial and contributed to improvements in team dynamics. Similarly, didactic sessions covering various topics such as hormone therapy initiation, primary care issues, advocacy, and psychotherapy were found effective in meeting learners’ objectives and enhancing their confidence in treating transgender veterans42.

Discussion

This scoping review examined telemedicine services within the LGBTQIA + community, focusing on GAC, mental health, STI, and HIV care, along with patient and provider satisfaction, and telemedicine use for training and interdisciplinary consultations. During COVID-19, remote methods like phone calls and video conferencing became crucial, whereas pre-pandemic options, particularly for transgender healthcare, were limited due to inadequate education and discrimination25. The introduction of telemedicine during COVID-19 led to increased patient utilization and reduced delays in providing GAC13. Appointment completion rates improved, cancellations decreased, and no-show rates were lower compared to in-person visits, especially in rural areas.

Similar findings were observed by Deguzman et al. and can be mainly attributed to easier accessibility, which proved to be a significant factor, with patients in rural areas, distant from healthcare facilities, exhibiting higher attendance rates for telemedicine appointments compared to their urban counterparts21. This highlights telemedicine’s advantage in offering quick and accessible care from home. However, findings from another study revealed slight differences in trends among urban populations. Specifically, a lower percentage of urban patients completed their appointments post–COVID-19 compared to the pre-pandemic period. In contrast, patients from rural areas showed an increase in appointment completion rates following the widespread adoption of telemedicine. This discrepancy is likely attributed to the fact that individuals in remote and rural settings benefited more from telemedicine, as it helped overcome geographical and travel-related cost barriers to healthcare access26.

Telehealth was especially preferred for services like hormone refills and lab result monitoring, as it reduces in-person visits and addresses distance and transportation barriers. Similar findings by Sequeira et al. indicated that most gender-diverse youth felt satisfied and comfortable with telemedicine32. However, limitations in the included studies highlight important factors to consider when interpreting results. For instance, one study used no-show rates to assess access to care but overlooked issues like scheduling challenges, inadequate parental support, and lack of awareness about available services21. However, grouping solely by medical records may have led to misclassification, especially for visits related to eating disorders and gender health, potentially underestimating no-show rates in these populations. Moreover, most studies relied on system-level data, lacking patient-level insights, which limited understanding of individual experiences, particularly for transgender patients seeking care during the pandemic21. Additionally, data were sourced from specific, select community-based clinics, limiting generalizability to other patients receiving care in other healthcare settings, such as private practices or academic institutions.

Only a few studies included subgroups within the LGBTQIA + population, such as intersex, asexual, and indigenous individuals, resulting in significant underrepresentation13. Lack of diversity in samples studied generally means that findings are not generalizable, and some studies might inadvertently fail to represent various healthcare needs and barriers. Most telehealth intervention studies lacked racial and ethnic diversity, and thus their applicability was limited to non-racially or ethnically diverse populations.

Another important point to consider is thatsome of these studies involved already experienced participants in telehealth which biases their acceptance of the interventions. The participant profiles have overlooked major factors such as intimate partner violence and relationship dynamics leaving much that could be present in the depth of the findings39,42. Critically evaluating these limitations highlights the need for more inclusive research designs that account for biases in study design, sample selection, and demographic representation.

Timely provision of telemedicine services helped improve overall mental health, as demonstrated by reduced rates of depression and suicidal ideation, as well as improved mental health scores. These results can be attributed to a positive health balance due to timely administration of key interventions17.

A noticeable positive trend towards the likelihood of accessing telemedicine services for HIV testing and counseling was observed, especially in the latter half of the pandemic. This trend aligns with other data, such as a study by Homkhan et al. on transgender women, which found telemedicine to be an effective alternative for accessing HIV testing, particularly among intravenous drug users20. The major reason for these findings could be the increased acceptance, resulting in patients feeling more comfortable and less concerned about confidentiality issues because of their remote nature. The patients felt more secure and were able to freely share their past sexual history without fear of being judged20.

Similarly, previous studies, such as Atkinson et al., have shown that many individuals in sexual minority groups perceive seeking mental or behavioral healthcare as stigmatizing. Telemedicine provides a more comfortable, judgment-free platform for accessing necessary care18. Additionally, intravenous drug users and transgender youth demonstrated a greater preference for telemedicine visits and higher acceptance of remote HIV testing over in-person services20. In contrast, Stekler et al. found no difference in STI treatment and screening rates between telemedicine users and in-person patients, possibly due to better healthcare access in that study setting and the advantages of building provider-patient relationships through face-to-face interactions49.

Our study shows that the satisfaction level with the use of telemedicine services varies depending on the type of services provided, according to both the patients and physicians. Studies conducted by Lucas et al.26 and Gava et al.17 revealed similar findings, which may be attributed to easier access to telemedicine, especially for individuals who cannot access care otherwise. Regarding mental health services, the results demonstrated significant improvements in patients’ mental health scores compared to individuals receiving no care at all17,26).

In terms of screening for STIs, patients generally found telemedicine services to be satisfactory, and a similar trend was observed by Rotheram et al. These findings could be attributed to the added patient benefits, such as both pre- and post-testing counseling in telemedicine consultations, providing opportunities to learn and discuss sexual health more comprehensively than traditional healthcare approaches11. It is noteworthy that black sexual minority groups reported satisfaction with virtual focus groups targeting HIV prevention, feeling more included and at ease around their own people30.

Telemedicine serves as a valuable tool for training and interdisciplinary services; several studies have demonstrated the pivotal role that telemedicine can play40,41,43. Interestingly, the utilization of telemedicine for interdisciplinary consultation and training has been shown to significantly enhance the quality of care among veteran groups40,41,43. These consultations facilitated the involvement of multiple disciplines, leading to a more comprehensive approach to medication, hormonal therapy, and psychiatric support42. The training programs also demonstrated an increase in confidence among healthcare providers in delivering services to transgender veterans in a more cooperative manner and with better teamwork.

Interdisciplinary telemedicine consultation has emerged as a valuable tool to enhance provision of comprehensive care to transgender individuals40,41. Telemedicine has proved to be a vital tool for communication with specialists primarily dealing with GAC. Sessions covering various topics, including hormone therapy initiation, primary care issues, advocacy, and psychotherapy, were found to be extremely effective. It also facilitated the establishment of a holistic approach with peer support networks, a patient-centered approach to care, and a safe space to address concerns ranging from medication management to mental health evaluations, enabling individuals to learn from other people’s experiences32. This interdisciplinary approach not only enhances individual provider knowledge but also fosters a collaborative environment where providers can learn from each other’s experiences and expertise.

However, telemedicine is associated with its idiosyncratic challenges. Our review revealed that the primary challenge faced by patients is difficult relationship dynamics with healthcare providers. Silva et al. reported similar issues, which were attributed to obstacles in establishing a doctor-patient relationship due to the remote nature of telemedicine care services47. For some patients, receiving HIV screening results via a phone call was inconvenient, as the timing was not suitable for receiving the results and they would opt for in-person services48. Additionally, technical difficulties are often encountered with the use of telemedicine, leading to deviations from the main objective of the appointment, which is to provide care12. Some patients also expressed hesitancy about video consultations due to privacy concerns.

Further, patients were concerned about the quality and safety of video visits being compromised and expressed concerns about potential misgendering. Some transgender youth requested to disable the camera during the consultation for fear that seeing their image may trigger body dysphoria. Hertling et al.15 showed that a handful of patients requested that additional healthcare providers be present during teleconsultation, which made them more comfortable. Thus, telemedicine may not be the optimal mode of consultation and communication for certain patients15. Unsurprisingly, teleconsultations were preferred by patients residing longer distances from healthcare facilities or in rural areas. Conversely, patients in urban areas and those with easier access to healthcare preferred in-person services. However, overall data points towards the utility and massive potential of telemedicine services among patients with both mental and chronic health conditions12.

The ethical considerations of telemedicine use are complex and merit in-depth examination, particularly with regard to LGBTQIA + people. The possibility of digital privacy breaches is a major concern, as it could expose private health data to hackers or unauthorized access, potentially leading to discrimination, particularly against patients in marginalized communities. This highlights the need for more stringent security protocols in telemedicine, especially for these vulnerable populations. Additionally, obtaining informed consent in telemedicine can be challenging, especially when there are linguistic and cultural barriers, or when patients may not fully understand the risks involved51.

Ensuring clear and culturally appropriate consent procedures is essential for an inclusive telemedicine experience. Culturally competent care, which includes avoiding misgendering and addressing specific health concerns of LGBTQIA + patients, is crucial. Research shows that implementing culturally appropriate telemedicine can significantly improve patient outcomes and trust. Transparency, community involvement in telehealth design, and ethical frameworks prioritizing patient autonomy and safety are vital to addressing ethical issues. Involving LGBTQIA + communities in developing telemedicine services ensures these initiatives meet the needs of underserved groups. Additionally, incorporating targeted curricula in medical schools and residency programs to enhance cultural competence and ethical communication is highly beneficial.

Our study indicates that physicians generally recognize the value of telemedicine, particularly for follow-up and monitoring, though they prefer in-person consultations for invasive procedures, aligning with Hertling et al.15. To enhance telehealth services for the LGBTQIA + community, we recommend several policy approaches: advocating for expanded telehealth services and insurance coverage, allocating funds for LGBTQIA+-specific telemedicine initiatives, and establishing inclusive telehealth guidelines to ensure all patients feel supported, respected, and safe in their care.

Strengths.

This study is among the first to broadly explore telemedicine’s impact on LGBTQIA + healthcare, providing insights for future research and policy development. It systematically examines gender-affirming hormone therapy, surgical consultations, mental health services, and HIV/STI testing, offering a comprehensive assessment of telemedicine’s applicability in meeting diverse healthcare needs. By including studies on transgender individuals, gender-diverse youth, non-binary persons, MSM, and transgender veterans, the review enhances the generalizability of its findings and highlights telemedicine’s potential to address healthcare disparities among marginalized groups.

Analyzing data from before and during the COVID-19 pandemic reveals trends in healthcare delivery preferences and highlights telemedicine’s evolving role. The review’s use of diverse methods—surveys, interviews, retrospective analyses, and telemedicine interactions—strengthens its conclusions. Emphasizing patient and provider satisfaction, along with mental health outcomes, underscores a commitment to patient-centered care and improving health-related quality of life for LGBTQIA + individuals52.

Limitations

Despite the strengths, several limitations were noted in the reviewed studies. Data constraints from electronic health records often lacked details about patient experiences, limiting understanding of telemedicine choices13,18. Many studies with smaller sample sizes provided more qualitative insights, often overlooking diversity in race and urban/rural contexts25.Survey completion rates varied, with some patients failing to complete surveys or being surveyed at different care stages, potentially affecting outcomes35.

Accessibility issues such as lack of internet access, affordable devices, and transportation barriers contributed to missed appointments21,31. Self-selection bias was common, with participants often having prior research involvement19,25,29. Recall and social desirability biases were also reported19,25. Gender identification expression was restricted in studies using multiple-choice online surveys46.

Disruptions during COVID-19 and temporary virtual care policies complicated the analysis, especially with regional differences in pandemic severity13,34. Some surveys were completed by family members instead of trans youth, affecting interpretation36. Privacy concerns for adolescents were often not addressed, potentially impacting findings47. Most surveys were conducted in the United States, limiting representation of areas with more conservative sexual health policies. However, a study in Italy, which was severely affected by the pandemic, reported higher telemedicine favorability.

Billability constraints and caps on virtual visits in some government administrations may also restrict telemedicine use34. Lastly, the learning curve for telemedicine usability for both patients and providers is a potential limitation31.

Summary and future prospects

Our study highlights the wide range of healthcare services effectively delivered via telemedicine, including GAC, mental health support, and STI screening. Telemedicine acts as a vital lifeline for the LGBTQIA + community, often facing systemic barriers and discrimination in accessing care. To enhance its impact, future strategies should target marginalized subgroups. For example, specialized telehealth programs for rural transgender youth can close gaps in gender-affirming treatment and mental health support, while digital mental health platforms can assist non-binary individuals who face challenges with in-person affirming care.

Telehealth also improves access to specialized care for intersex individuals, regardless of location. However, many providers report insufficient training in telemedicine, emphasizing the need for comprehensive education programs tailored to its nuances. The significance of telemedicine extends beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, indicating its lasting role in healthcare delivery. While the future of telemedicine is promising, it’s crucial to address ongoing challenges like technology constraints, resistance, and digital inequality. Community outreach and education can help raise awareness of telemedicine’s benefits, while improving access to technology is vital for equitable healthcare in underserved areas. Ongoing training for healthcare providers on LGBTQIA+-affirming care will enhance patient experiences and foster inclusivity.

Conclusions

Our findings provide valuable insights for healthcare policymakers and practitioners to develop inclusive telemedicine policies, promote equitable access to digital health services, and implement training programs that enhance the cultural competence of healthcare professionals in caring for LGBTQIA + populations. This study urges healthcare institutions and policymakers to prioritize funding and the development of telehealth programs tailored to the specific healthcare needs of LGBTQIA + communities.

Data availability

All data can be requested upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Rice, D. L. G. B. T. Q. The communities within a community. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 23(6), 668–671. https://doi.org/10.1188/19.CJON.668-671 (2019).

Anonymous. National Center for HIV. Viral Hepatitis, STD, and Tuberculosis Prevention | CDC NCHHSTP. n.d. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/index.html [Last accessed: 10/26/2024].

Taskin, L. et al. Sexual health/reproductive Health-Related problems of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people in Turkey and their Health-Care needs. Florence Nightingale J. Nurs. 28(1), 97–109. https://doi.org/10.5152/FNJN.2020.19032 (2020).

Graham, K. K. Erasure on All Sides: A Public Health Analysis of Mental Health Erasure on All Sides: A Public Health Analysis of Mental Health Disparities (2019).

Budge, S. L., Adelson, J. L. & Howard, K. A. S. Anxiety and depression in transgender individuals: the roles of transition status, loss, social support, and coping. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 81(3), 545–557. https://doi.org/10.1037/A0031774 (2013).

Mereish, E. H., Katz-Wise, S. L. & Woulfe, J. We’re here and we’re Queer: sexual orientation and sexual fluidity differences between bisexual and Queer women. J. Bisex. 17(1), 125–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2016.1217448 (2017).

Moran, C. LGBTQ population health policy advocacy. Educ. Health (Abingdon). 34(1), 19–21 (2021).

Radix, A. E. et al. Transgender individuals and digital health. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 19(6), 592–599. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11904-022-00629-7 (2022).

Waad, A. Caring for our community: telehealth interventions as a promising practice for addressing population health disparities of LGBTQ + Communities in health care settings. Dela J. Public. Health. 5(3). https://doi.org/10.32481/DJPH.2019.06.005 (2019).

Nelson, R. Telemedicine and telehealth: the potential to improve rural access to care. Am. J. Nurs. 117(6), 17–18. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000520244.60138.1C (2017).

Rotheram-Borus, M. J., Lee, S. J. & Swendeman, D. Getting to zero HIV among youth: moving beyond medical sites. JAMA Pediatr. 172(12), 1117–1118. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMAPEDIATRICS.2018.3672 (2018).

Rogers, B. G. et al. Development of telemedicine infrastructure at an LGBTQ + Clinic to support HIV prevention and care in response to COVID-19, Providence, RI. AIDS Behav. 24(10), 2743. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10461-020-02895-1 (2020).

Lock, L., Anderson, B. & Hill, B. J. Transgender care and the COVID-19 pandemic: exploring the initiation and continuation of transgender care In-Person and through telehealth. Transgend Health. 7(2), 165–169. https://doi.org/10.1089/TRGH.2020.0161 (2022).

Apple, D. E. et al. Acceptability of telehealth for gender-Affirming care in transgender and gender diverse youth and their caregivers. Transgend Health. 7(2), 159. https://doi.org/10.1089/TRGH.2020.0166 (2022).

Hertling, S. et al. Acceptance, use, and barriers of telemedicine in transgender health care in times of SARS-CoV-2: nationwide Cross-sectional survey. JMIR Public. Health Surveill. 7(12). https://doi.org/10.2196/30278 (2021).

Tricco, A. C. et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850 (2018).

Gava, G., Seracchioli, R. & Meriggiola, M. C. Telemedicine for endocrinological care of transgender subjects during COVID-19 pandemic. Evid. Based Ment Health. 23(4), E1. https://doi.org/10.1136/EBMENTAL-2020-300201 (2020).

Atkinson, E., Galinkala, P. & Campos-Castillo, C. Telehealth use in 2022 among US adults by sexual orientation. Am. J. Manag Care. 30(1), E19–E25. https://doi.org/10.37765/AJMC.2024.89490 (2024).

Russell, M. R. et al. Increasing access to care for transgender/gender diverse youth using telehealth: A quality improvement project. Telemed J. E Health. 28(6), 847–857. https://doi.org/10.1089/TMJ.2021.0268 (2022).

Homkham, N. et al. A comparative study of transgender women accessing HIV testing via face-to-face and telemedicine services in Chiang Mai, Thailand during the COVID-19 pandemic and their risk of being HIV-positive. BMC Public. Health. 23(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/S12889-023-17124-2 (2023).

DeGuzman, P. B. et al. Impact of telemedicine on access to care for rural transgender and Gender-Diverse youth. J. Pediatr. (Rio J). 267 https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPEDS.2024.113911 (2024).

Gava, G. et al. Mental health and endocrine telemedicine consultations in transgender subjects during the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy: A Cross-Sectional Web-Based survey. J. Sex. Med. 18(5), 900–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JSXM.2021.03.009 (2021).

Garrett, C. C. et al. Young People’s views on the potential use of telemedicine consultations for sexual health: results of a National survey. BMC Infect. Dis. 11 https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-11-285 (2011).

Stephenson, R. et al. Project Moxie: results of a feasibility study of a telehealth intervention to increase HIV testing among binary and nonbinary transgender youth. AIDS Behav. 24(5), 1517–1530. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10461-019-02741-Z (2020).

Kloer, C., Lewis, H. C. & Rezak, K. Delays in gender affirming healthcare due to COVID-19 are mitigated by expansion of telemedicine. Am. J. Surg. 225(2), 367–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AMJSURG.2022.09.036 (2023).

Lucas, R. et al. Telemedicine utilization among transgender and Gender-Diverse adolescents before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Telemed J. E Health. 29(9), 1304–1311. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2022.0382 (2023).

Berry, K. R. et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, Queer, intersex, asexual, and other minoritized gender and sexual Identities-Adapted telehealth intensive outpatient program for youth and young adults: subgroup analysis of acuity and improvement following treatment. JMIR Form. Res. 7(1), e45796. https://doi.org/10.2196/45796 (2023).

Sullivan, S., Sullivan, P. & Stephenson, R. Acceptability and feasibility of a telehealth intervention for sexually transmitted infection testing among male couples: protocol for a pilot study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 8(10), e14481. https://doi.org/10.2196/14481 (2019).

Mwaniki, S. W. et al. What if I get sick, where shall I go? A qualitative investigation of healthcare engagement among young gay and bisexual men in Nairobi, Kenya. BMC Public. Health. 24(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/S12889-023-17555-X (2024).

Dangerfield, D. T., Wylie, C. & Anderson, J. N. Conducting virtual, synchronous focus groups among black sexual minority men: qualitative study. JMIR Public. Health Surveill. 7(2). https://doi.org/10.2196/22980 (2021).

Grasso, C. et al. Gender-Affirming care without walls: utilization of telehealth services by transgender and gender diverse people at a federally qualified health center. Transgend Health. 7(2), 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1089/TRGH.2020.0155 (2022).

Sequeira, G. M. et al. Pediatric primary care providers’ perspectives on telehealth platforms to support care for transgender and Gender-Diverse youths: exploratory qualitative study. JMIR Hum. Factors. 10, e39118–e39118. https://doi.org/10.2196/39118 (2023).

Guy, A. A. et al. Transgender and gender diverse adults’ reflections on alcohol counseling and recommendations for providers. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry. 93(2), 166–175. https://doi.org/10.1037/ORT0000663 (2023).

Navarro, J. M., Scheim, A. I. & Bauer, G. R. The preferences of transgender and nonbinary people for virtual health care after the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada: Cross-sectional study. J. Med. Internet Res. 24(10). https://doi.org/10.2196/40989 (2022).

Smalley, J. M. et al. Improving global access to transgender health care: outcomes of a telehealth quality improvement study for the air force transgender program. Transgend Health. 7(2), 150–158. https://doi.org/10.1089/TRGH.2020.0167 (2022).

Hedrick, H. R. et al. A new virtual reality: benefits and barriers to providing pediatric Gender-Affirming health care through telehealth. Transgend Health. 7(2), 144–149. https://doi.org/10.1089/TRGH.2020.0159 (2022).

Phanuphak, N. et al. What would you choose: online or offline or mixed services? Feasibility of online HIV counselling and testing among Thai men who have sex with men and transgender women and factors associated with service uptake. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 21(Suppl 5(Suppl Suppl 5), 82–94. https://doi.org/10.1002/JIA2.25118 (2018).

Phanuphak, N. et al. Linkages to HIV confirmatory testing and antiretroviral therapy after online, supervised, HIV self-testing among Thai men who have sex with men and transgender women. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 23(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25448 (2020).

Craig, S. L. et al. AFFIRM online: utilising an affirmative Cognitive-Behavioural digital intervention to improve mental health, access, and engagement among LGBTQA + Youth and young adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH18041541 (2021).

Kauth, M. R. et al. Teleconsultation and training of VHA providers on transgender care: implementation of a multisite hub system. Telemed J. E Health. 21(12), 1012–1018. https://doi.org/10.1089/TMJ.2015.0010 (2015).

Shipherd, J. C. et al. Interdisciplinary transgender veteran care: development of a core curriculum for VHA providers. Transgend Health. 1(1), 54–62. https://doi.org/10.1089/TRGH.2015.0004 (2016).

Shipherd, J. C., Kauth, M. R. & Matza, A. Nationwide interdisciplinary E-Consultation on transgender care in the veterans health administration. Telemed J. E Health. 22(12), 1008–1012. https://doi.org/10.1089/TMJ.2016.0013 (2016).

Blosnich, J. R. et al. Utilization of the veterans affairs’ transgender E-consultation program by health care providers: Mixed-Methods study. JMIR Med. Inf. 7(1). https://doi.org/10.2196/11695 (2019).

Anonymous & A Feasibility Study of a Telehealth Intervention on Health Care Service Utilization among Transgender Women of Color in Washington., DC. n.d. https://eurekamag.com/research/081/001/081001410.php [Last accessed: 10/26/2024].

Magnus, M. et al. Development of a telehealth intervention to promote care-seeking among transgender women of color in Washington, DC. Public. Health Nurs. 37(2), 262–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12709 (2020).

Sequeira, G. M. et al. Transgender youths’ perspectives on telehealth for delivery of Gender-Affirming care. J. Adolesc. Health. 68(6), 1207–1210. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JADOHEALTH.2020.08.028 (2021).

Silva, C. et al. Usability of virtual visits for the routine clinical care of trans youth during the COVID-19 pandemic: youth and caregiver perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18(21). https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH182111321 (2021).

D’Angelo, A. B. et al. Experiences receiving HIV-Positive results by phone: acceptability and implications for clinical and behavioral research. AIDS Behav. 25(3), 709–720. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10461-020-03027-5 (2021).

Stekler, J. D. et al. HIV Pre-exposure prophylaxis prescribing through telehealth. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 77(5), e40–e42. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001621 (2018).

Sharma, A. et al. Variations in testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections across gender identity among transgender youth. Transgend Health. 4(1), 46–57. https://doi.org/10.1089/TRGH.2018.0047 (2019).

Nittari, G. et al. Telemedicine practice: review of the current ethical and legal challenges. Telemed J. E Health. 26(12), 1427–1437. https://doi.org/10.1089/TMJ.2019.0158 (2020).

Vosburg, R. W. & Robinson, K. A. Telemedicine in primary care during the COVID-19 pandemic: provider and patient satisfaction examined. Telemed J. E Health. 28(2), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1089/TMJ.2021.0174 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.G.: conceptualization, data curation, methodology, project administration, writing-original draft, writing-review and writing. K.T.: data curation, methodology, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing. H.Q.A.: data curation, methodology, writing-original draft, writing-review and writing. S.H.: data curation, methodology, writing-review and writing. U.S.: data curation, writing-original draft, writing-review and writing. H.S.: writing-original draft, writing-review and writing. T.E.G.: writing-original draft, writing-review and writing. D.N.R.: writing-original draft, writing-review and writing. A.H.S.: project administration, supervision, validation, writing-original draft, writing-review and writing. M.D.:writing-original draft, writing-review and writing. A.B.S.: conceptualization, project administration, supervision, validation, writing-original draft, writing-review and writing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Goyal, A., Thakkar, K., Abbasi, H.Q. et al. Utilization of telemedicine in healthcare delivery to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual, other sexual and gender minority (LGBTQIA+) populations: a scoping review. Sci Rep 15, 29010 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97797-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97797-4