Abstract

Mobile phone addiction (MPA) is widespread on university campuses and has many negative effects on individuals. A good physical activity atmosphere (PAA) has been shown to be effective in improving individuals’ mental health, including psychological resilience (PR), but it is not clear whether it can alleviate MPA. Therefore, this study investigates the effects of both on MPA through a longitudinal study and provides a theoretical basis for reference. A total of 964 international students from different countries were selected from 8 colleges and universities in Beijing, and 2 longitudinal follow-up surveys were conducted using the Physical Activity Atmosphere Scale, the Psychological Resilience Scale, and the Mobile Phone Addiction Scale. Correlation and path model analyses were conducted using Pearson and cross-lagged panel model (CLPM). The correlation results showed that T1-PAA, T2-PAA were significantly positively correlated with T1-PR, T2-PR (r = 0.577, 0.306, P < 0.001) and T1-PR, T2-PR were significantly negatively correlated with T1-MPA, T2-MPA (= -0.225, -0.236, P < 0.001). CLPM results showed that college student PAA stably positively predicted PR (t = 0.518, P < 0.001). PAA (t = -0.131, P < 0.001) and PR (t = -0.159, P < 0.001) negatively predicted MPA levels. (1) Improving PAA not only alleviates MPA in college students, but also improves PR levels. (2) PR also has an inhibitory effect on MPA, so increasing PR will enhance the effect of PAA. (3) PAA negatively predicts MPA and positively predicts PR in college students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the development of modern society and science and technology, people’s frequency and time of using electronic screens and smart devices have gradually increased, which has caused some negative effects. Among them, mobile phone addiction (MPA) is a representative negative phenomenon, especially in university campuses where MPA is more common1. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the global MPA rate among the youth population is as high as 14.3 per cent.2 In China, the rate rose to 24 per cent during the epidemic, according to two large Chinese surveys2,3. Particularly on university campuses, students are less constrained by their families or schools, which has led to a gradual increase in the proportion of MPAs among students, making them the largest potential population4. Studies have shown that gender, anxiety, depression, loneliness, stress, well-being, social support and resilience are all predisposing factors for MPA5. For college students, although the constraints from their families are reduced, academic pressures, interpersonal interactions and employment demands may lead to a gradual increase in the incidence of MPA6. Therefore, there is an urgent need to prevent and intervene in MPA among college students.

A large body of research has shown that physical activity (PA), as a non-pharmacological intervention, has a significant effect on improving individuals’ mental health and problem behaviours7. However, few studies have examined the factors that contribute to individuals engaging in PA. The WHO Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) 2023 suggests that the effects of PA on individuals’ mental health are significant, but are influenced by a number of factors. Among these factors, the physical activity atmosphere (PAA) is an important determinant of an individual’s level of PA8. A positive PAA can encourage the surrounding population to actively engage in physical activity and develop regular fitness habits9. Behavioral theory suggests that students at the developmental stage of social adjustment are prone to develop psychological traits and behaviors in a peer-supportive environment. PAA covers sports information, peer support and the benefits of a good sports environment for social development and healthy behaviour10. On the other hand, psychological resilience (PR) refers to an individual’s ability to cope positively with stress and frustration in social life11. Research has shown that team sports such as basketball and football, which are played in a teamwork and competitive environment, require more effort from participants and have a positive effect on students’ PR12. Individuals with higher levels of PR, on the other hand, tend to be emotionally stable, have strong social adaptability and emotional management skills, are better able to focus on their goals in the face of a task, and are able to cope with negative life learning events even when they are encountered with positive attitudes, and do not experience MPA behaviors and academic procrastination13.

In conclusion, there may be interaction between PAA, PR and MPA among students. At the same time, there may also be gender differences. Previous cross-sectional studies have only shown correlation between variables, and it is difficult to show unidirectional causality, which makes the findings not generalizable. Therefore, this study uses the cross-lagged panel model (CLPM) to examine the causal relationship between variables in terms of time series, which overcomes the limitations of cross-sectional studies and makes the conclusions more representative and stable14. Specifically, this study investigated and constructed a causal model of PAA, PR, and MPA among college students through a two-phase longitudinal survey conducted over a six-month period, with the aim of exploring the intrinsic relationship between variables affecting college students’ MPA and providing evidence for a scientific intervention on college students’ MPA. Based on previous literature, the following hypotheses were proposed: (I) PAA, PR and MPA are significantly correlated. (II) PAA and PR can negatively predict MPA.

Materials and methods

Participants

Using the cluster random sampling method, 964 international students from different countries from 8 universities in China were initially selected as the subjects of the study, taking the international student classes in each university as the unit. The inclusion criteria for the subjects were: (1) Current exchange or international students, including undergraduate, master’s, and doctoral students. (2) They were conscious and able to complete the questionnaire without difficulty and had no history of intellectual disability or mental illness. (3) Subjects volunteered to participate in this study and did not refuse to complete the survey. (4) Informed consent for the survey was given by the counselor (classroom teacher), and the questionnaire was completed after signing it. The procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines and were approved by the Ethics Committee of Human Experimentation of Beijing Normal University (Authorization no. TY20220905). A statement to confirm that all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent form was obtained from all subjects. The detail is shown in Table 1.

Procedures

In this study, the subjects PAA, PR and MPA parameters were measured using scales based on various indicators. During the testing process, all indicators were distributed through SoJum Software (Tencent Holdings Ltd.). Prior to data collection, the purpose and methodology of the survey were explained to the respondents in person, and any questions were answered in person, with the consent of the counsellor (class teacher) and the consent of the participant. The scale was completed anonymously, without personal information such as ID number or student number, excluding invalid answers, short time (less than 200 s), 10 consecutive questions with the same option, and questionnaires with high homogeneity.

Measurements

Physical activity atmosphere assessment

The PAA scale used in this study was revised by Liu et al.15. The initial version of the scale was in Chinese, but considering that most of the participants were international students, the scale was translated into English, and after proofreading and reliability testing, the scale was finalised in English. The reliability of the scale was also confirmed by Li’s study16. The scale consists of five dimensions: interpersonal association, natural association, access to information, interpersonal barriers and conditional barriers, with a total of 17 items. The scale is scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘1’ (strongly disagree) to ‘5’ (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating higher PAA. Cronbach’s α for the scale in the pre- and post-tests of this study were 0.804 (T1) and 0.839 (T2) respectively.

Psychological resilience survey

The PRS scale used in this study was originally co-developed by Hu et al.17. The original version of this scale is in English, so there is no need to translate it. The reliability of the scale was also confirmed in Lau’s study18. The scale consists of 27 questions in 5 dimensions, which students are asked to complete according to their actual situation. The scale uses the Likert 5-point scale to assess students’ PR level, ranging from “1” (not at all compliant) to “5” (fully compliant), with higher total scores indicating higher PR levels. The Cronbach’s α of the scale was 0.775 (T1) and 0.816 (T2) at the pre- and post-test of this study.

Mobile phone addiction evaluation

The MPA scale used in this study was developed by Wang et al.19. As mentioned above, the scale was initially written in Chinese and, after translation and proofreading, it was administered to participants via an English questionnaire. The scale was also used in Feng’s study20. The scale consists of 16 questions with 3 dimensions, namely withdrawal, salience and compulsivity. The scale uses a 5-point Likert scale to assess MPA in secondary school students, with scores ranging from ‘1’ (extremely non-compliant) to ‘5’ (very compliant), and a total score of more than 45 points is the criterion for MPA. The Cronbach’s alpha for the pre- and post-test scales in this study were 0.879 (T1) and 0.862 (T2) respectively.

Cross-lagged panel model construction

The cross-lagged panel model (CLPM) will be constructed based on the results of the 2 measurements by taking 2 longitudinal follow-up measurements of all participants at the following points21: T1: September 2022 and T2: March 2023. Specifically, the 2 measurements of PAA will be used as the main variable and PR will be used as a mediator variable to observe the positive or negative predictive effect of PAA on MPA, which is the main dependent variable. The results obtained on two occasions were tested for consistency according to Andersen’s method and the PAA, PR, and MPA of the international students were tested for gender and age equivalence by baseline equivalence, load equivalence and intercept equivalence in that order22. Andersen’s consistency test is mainly used to verify that measurement models (e.g. factor structures) are equivalent across time points or groups, and to avoid biases in the estimation of structural models (e.g. cross-lagged effects) due to differences in measurement instruments. The process requires configural invariance, metric invariance, scalar invariance, and strict invariance. Finally, the significance of the model is determined using the fit indices (e.g., ΔCFI ≤ 0.01 or ΔRMSEA ≤ 0.015). The specific reason for this is because of the need to exclude measurement bias (in this study, e.g., T1-PAA→T2- MPA) during the CLPM building process, to ensure the validity of the measurement-equivalent latent variable model, and to verify that the results support the time-series effect among variables (e.g., from T1→T2). In this study, Model-1 is the baseline equivalent model, Model-2 is the load equivalent model.

Statistical analysis

In this study, we mainly used comparison of differences, correlation analysis and CLPM to analyze the different indicators. First, SPSS 21.0 was used to test the normality of PAA, PR, and MPA one by one, and descriptive statistics were performed after determining the types of data. Bartlett’s test of sphericity, for data that did not meet the assumptions, the Greenhouse-Geisser method was used to correct the data23. To explore the correlation and effect size between variables, Pearson’s test was used to analyze the results and r and P values were reported. After screening the correlation results, valid variables were included in the CLPM by AMOS 24.0 for fitting to explore the path characteristics between variables. After standardizing each result, the CLPM test and confidence interval estimation were performed using model-6 in the SPSS process canonical macro plug-in. The significance of each path was then tested using the bootstrap method24. Finally, the Bonferroni test was used for post hoc testing of all indicators, with a significant threshold of P < 0.05.

Results

The results of this study were collected twice over a period of six months. Of these, the first collection (T1) had a compliance of 95.74% with a loss of 41 samples. The second collection (T2) had a compliance of 89.83% and a loss of 57 samples. The researchers also reported that no risky events occurred during the entire experiment.

Common method deviation test results

In this study, the use of multiple self-report questionnaires to measure the same group of people can easily lead to the problem of common methodological bias. In this paper, we train the subjects before distributing the questionnaires and use various methods to minimize the influence of the self-assessment methods on the results of the study, such as standardized instructions, strict control of the time taken to complete the questionnaires, mixing the distribution of positive and negative questions, and controlling demographic variables. Meanwhile, an exploratory factor analysis of all question items of the PAA, PR and MPA scales for college students was conducted using Harman’s one-way test, and a total of 13 factors had eigenvalues greater than 1 when the factors were not rotated, and the first factor explained 14% of the variance, which did not reach the required critical level of 40%. Therefore, there is no general methodological bias in this study.

Correlation test results between variables

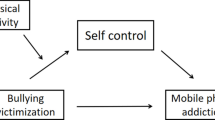

The correlation results showed that, by Pearson correlation test for PAA, PR, and MPA of college students (see Table 2): T1-PAA and T2-PAA, T1-PR and T2-PR, and T1-MPA and T2-MPA showed significant positive correlation. Simultaneous correlation tests: T1-PAA, T1-PR, T1-MPA were significantly correlated; T2-PAA, T2-PR, T2-MPA were significantly correlated. College students’ PAA, PR and MPA showed significant correlations in both pre-test and post-test, indicating that PAA, PR and MPA satisfy the inter-temporal stability and synchronous correlation of 6 months, which is suitable for cross-lagged analysis. The results also indicate that more than 90% of the main variables and sub-indicators are significantly correlated with each other, which can be further tested for mediation effects25. See Table 1; Fig. 1 for more information.

Cross-lagged panel model consistency test results

In order to test the measurement consistency of the model, the study was conducted in three steps (baseline equivalence, loaded equivalence, and intercept equivalence) to test the equivalence of PAA, PR, and MPA across gender and age. The results showed that PAA and PR were consistent across gender and age, while MPA was consistent across age. There were differences in MPA loadings and intercepts by gender, but no statistically significant differences were found between the 2 adjacent time points (ΔCF1 < 0.01), so the model fit indices were good. In conclusion, the subjects PAA, PR, and MPA measurement items, latent factor meanings, and measurement reference points were highly consistent across gender and age, and the results were comparable across gender and age.

The data were also tested for common method bias using the Harman one-way test26. A total of 3 tests were conducted, the 1st measurement eigenvalue greater than 1 factor total 17, the maximum factor variance explained rate is < 40%. The 2nd test measured 12 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, and the maximum factor variance explained was < 40%. The third measurement had 11 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, and the maximum factor variance explained was < 40%. There is no serious common method bias problem in all three measurements. See Table 3.

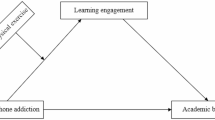

Cross-lagged panel model path and fitting degree results

In this study, we used AMOS software to construct CLPM to test the cross-lag model of PAA, PR and MPA in college sports. The model fit metrics showed that X2/df = 2.205 (P < 0.001, n = 964), and the goodness-of-fit metrics: CFI = 0.941, NFI = 0.934, CFI = 0.945. This result indicated that the cross-lagged model fit was high. In particular, T1-PAA had a significant effect on T2-PAA (β = 0.423, P < 0.01), T2-PR (B = 0.135, P < 0.01), and T2-MPA (B = -0.163, P < 0.01); T1-PR had a significant effect on T2-PAA (β = 0.411, P < 0.01), T2-PR (β = 0.557, P < 0.01), and T2-MPA (β = -0.148, P < 0.01). T1-MPA had a significant effect on T2-PR (β = -0.140, P < 0.05), T2-MPA (β = 0.512, P < 0.01), and a non-significant effect on T2-PAA (β = -0.019, P > 0.05).

According to the M.C.EISMA method27, the causal relationship between variables A and B is examined, if the correlation between the pre-test variable A and the post-test variable B is greater than the relationship between the pre-test variable B and the post-test variable A, it can be inferred that there is a causal relationship between variables A and B, and that variable A is the cause variable of variable B. Combined with the path coefficients of the cross-lagged model, it can be seen that PAA is the cause variable of college students‘ PR, MPA, and PR is the cause variable of MPA, and from the relationship of the correlated variables, PR may be the mediator of college students’ PAA affecting MPA, and the detailed information is shown in Fig. 2.

Multi-structural equation modeling results

Meanwhile, in this study, multiple sets of structural equations were used to model the baseline model (M0) and the restricted model (cross-lagged paths M1 for boys and girls, and structural intercept M2, structural covariance M3, etc.), and model comparisons were made to examine whether there were gender differences in the cross-lagged relationships of the variables. The results showed that the models M1 to M3 were well fitted and the differences from the baseline model (CFI = 0.941, TLI = 0.873, RMSEA = 0.12, 90%CI = [0.10, 0.14], P < 0.01) were not statistically significant (∆CFI < 0.05, P > 0.05), i.e., PAA, PR, and MPA for all participants There was no statistically significant difference in the cross-lagged relationship between the sexes. See Table 4.

Discussion

MPA is a maladaptive behavioral habit that is common on college campuses, and chronic MPA can trigger numerous risk factors, including symptoms such as decreased academic performance, impaired mental health, or the development of aggressive behavior28. Numerous studies have shown that PA can effectively alleviate MPA symptoms in students and improve PR to help them establish better study habits29,30. However, few studies have been able to clarify whether there is a longitudinal interaction between the three. Therefore, the present study was the first to examine the association between PAA, PR and MPA in college students through a longitudinal study with a cross-lagged research design over a period of 6 months and two phases to reveal the intrinsic influence of PAA on college students’ MPA. The study concluded that PAA can directly affect MPA or indirectly improve MPA by increasing PR. Creating a good campus sports PAA can effectively improve college students’ MPA phenomenon, which is conducive to the development of interpersonal relationships and the improvement of college students’ PR level.

The first finding of this study is that PAA can stably and positively predict the PR of college students. In this study, PAA was significantly and positively correlated with individuals’ PR and was not affected by the factors of gender and age. At the same time, the effect sizes of the positive influence of PAA on PR were all greater than 0.4, so it can be judged that the benign influence of PAA on individual PR is very effective. So far, hypothesis (I) can be accepted. Contrary to previous studies, college students’ PAA has a significant predictive effect on individual PR levels, and PAA as a supporting element can improve college students’ knowledge and understanding of physical activity31,32. The higher the PAA, the more information about sport the individual receives, the more the individual feels the exercise environment of peer encouragement, support and supervision, and the more the individual recognizes the multiple physical and mental health values of exercise and the positive experience of exercise, which strengthens the participant’s mastery of health knowledge and exercise skills, and integrates exercise into the individual’s life and healthy lifestyle33. When college students have good PAA, they get more peer support factors and a relaxing and pleasant exercise environment, overcome more of their own physiological and psychological barriers during exercise, reduce tension and anxiety, improve stress resistance and interpersonal relationships, strengthen the honing of their willpower, and thus improve the level of college students’ PR34. In good PAA, college students have to mobilize more attention and cognitive capacity to cope with situations in sport, and the constraints of the rules of sport expose the individual to a collective and jointly supervised environment, which in the long run leads to an increase in students’ PR levels35. If students do not have a good PAA, individual exercise lacks a supportive environment with a supervised atmosphere, and if they encounter difficulties during exercise, they may choose to procrastinate, avoid challenging exercises and have lower PR levels36.

The second finding of this study was that PAA was a stable predictor of MPA in college students. In this study, PAA showed a significant negative correlation with MPA and remained independent of gender and age factors. Meanwhile, the magnitude of the negative effect of PAA on MPA exceeded that of PR, so it can be judged that good PAA is an important way to improve individual MPA. The validity of hypothesis (I) was also tested again. Previous studies have shown that PAA is a motivational factor that promotes the refinement of exercise information, enriches individual exercise experiences and forms active exercise habits. Good PAA can internalize students’ understanding of the value of sport and stimulate the individual’s emotional experience to actively integrate into the exercise environment37. Good PAA can also lead to harmonious peer relationships, providing students with informational, emotional and behavioral support for physical activity. Students can improve their motor skills and self-esteem through frequent peer interactions, build exercise expectations in a supportive environment with peers, share exercise information and form an exercise circle with common interests, so that students feel a sense of belonging to exercise and are more likely to have a pleasurable exercise experience38. There is also a greater tendency to engage in repeated and sustained physical activity to satisfy individual social needs and exercise psychology39. A good PAA provides a positive and supportive environment with rich and varied sports information so that students can increase their motivation to exercise, focus their attention on sport, actively experience the enjoyment of sport, and actively overcome the negative consequences of MPA on the individual in order to develop a healthy lifestyle40. Poor PAA do not get support and guidance from teachers and peers on exercise emotions, exercise behavior, lack of common exercise, mutually supportive exercise environment and sufficient exercise information, and when they encounter difficulties in exercising, they prefer to use mobile phones to vent their emotions or relieve stress through entertainment and interpersonal communication41.

The final finding of this study was that students’ PR predicted MPA over a long period of time. In this study, the negative effect of PR on MPA was significant. Meanwhile, the longitudinal results showed that the degree of negative effect of PR on MPA did not decrease but increased at T1 and T2 stages separated by 6 months. Therefore, this study concluded that the inhibitory effect of PR on MPA is long-lasting. Previous studies have shown that PR is an individual’s positive ability to cope with frustration or stress, and that regular participation in physical activity leads to an increase in PR, while individuals with high PR have strong self-management and discipline, and show strong adaptive capacity in life and study42. Individuals have greater control over maladaptive behaviors when they have a strong PR, and their good self-management skills avoid spending more time on their mobile phones, which in turn reduces the incidence of MPA43. Individuals with high PR tend to be emotionally stable, have strong social adaptability and emotional management skills, are better able to focus on goals when faced with tasks, and are able to cope with negative life learning events even when they are faced with positive attitudes, and do not experience MPA behaviors and academic procrastination44. However, those with low PR are unable to cope with the pressures and frustrations of life, study and tend to indulge in mobile phone use to avoid the obstacles of reality. When faced with setbacks in exercise, they tend to avoid, cannot control their own emotions and behavior, lack the ability to organize and manage the exercise tasks set, are easily distracted, and often turn to mobile phones to relieve their negative psychology, which is prone to the development of MPA45.

Cross-lagged analyses also revealed that PR may have a mediating effect in the process of students’ PAA affecting MPA. In the present study, there was a direct effect of PAA on MPA and a positive moderating effect of PR on this pathway. This is mainly reflected in the fact that PR acts as a mediator and enhances the negative inhibitory effect of PAA on MPA. At this stage, hypothesis (II) can be accepted. Previous research has shown that the multiple supportive environments provided by PAA can promote individual psychological growth, and that the collective sense of belonging that PAA provides to students can also be beneficial46. Adequate information about exercise and positive peer relationships can provide emotional support for students to continue to participate in exercise, helping them to understand the value and effectiveness of physical activity and to see exercise as a positive and beneficial lifestyle choice that is consistent with their self-development47. The mutually supportive training environment enables students to overcome more of their own physical and psychological barriers, strengthens their willpower and effectively improves their PR levels48. In a collaboratively supervised and supported environment, exercise behaviors have higher levels of autonomy and adherence, with significant improvements in students’ resilience and interpersonal relationships, as well as the ability of individuals to remain positively engaged in exercise when faced with exercise difficulties or temptations to engage in entertainment, such as mobile phones49. Improved PR will enable students to experience fun and positive emotions during exercise, become more confident when frustrated during physical activity, actively overcome the urge to overuse mobile phones, consciously change bad mobile phone use habits, improve individual internal motivation, consciously regulate emotions, behaviors, and reduce MPA50. At the same time, actively creating a good PAA can not only improve the PR level of college students, but also improve the autonomy and persistence of physical exercise. If there is no good PAA, students’ autonomy in exercise is not high, there is a lack of support and encouragement from parents, teachers and peers, and the interpersonal relationship between supervision and encouragement in exercise cannot be formed51. It is not easy for students to get appropriate information about exercise, students’ perceptions of the value of exercise and sport are not clear, students’ motivation to be active is weakened, and students’ PR is weakened52. When physically challenged, they turn to relatively easy gaming entertainment to avoid negative evaluations, are less resistant to the virtual world, are more likely to seek alternative emotions via mobile phones, and are more likely to develop MPA53.

In summary, students’ PAA, PR and MPA have synchronous and stable correlations. Therefore, this study used cross-lag analysis to confirm the causal relationship of the variables, in which college students’ PAA is the cause variable of PR and MPA, and PR is the cause variable of college students’ MPA. Furthermore, the relationship between the variables suggests that PR may have a mediating effect in the process of college students’ PAA influencing MPA. Therefore, combining the above results, this study concluded that creating a good PAA is conducive to reducing MPA, while effectively improving students’ PR and helping them establish good mental health.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

In this study, we constructed a cross-lagged panel model to investigate whether PAA can influence college students’ MPA and PR over time, with the aim of reducing and preventing the likelihood of college students’ MPA and increasing PR to inhibit the occurrence of MPA or other problematic behaviors. At the same time, we included international students from eight universities in Beijing through a large-sample survey and follow-up interviews, and constructed multiple horizontal and vertical pathways of significant effects among the variables. However, there are several limitations to this study.

Firstly, although the three indicators were included in this study and follow-up was carried out at six-month intervals. However, the experiment did not continue with the follow-up, so the whole process of investigation did not exceed 1 year and did not sufficiently prove the timeliness between the three variables. Therefore, we will continue to deepen this study in the future and strive for the collection and follow-up time to reach more than 3 years, which has fully proved the validity of the overall results, and construct the prediction model of the three indicators in a certain region by region. To prevent and suppress the incidence of MPA among college students.

Secondly, as to why PAA was chosen for this study rather than traditional physical activity (PA), this is because a large number of previous studies have shown that PA has a significant effect on individuals’ mental health and quality of life. This is because many previous studies have shown that PA has a significant effect on individuals’ mental health and quality of life. Therefore, this question does not require much empirical evidence from subsequent studies. However, the number of relevant studies on the influencing factors that contribute to individuals performing PA is limited. Therefore, this study shifted the main variable to PAA and went to explore how to create an exercise environment and atmosphere that helps college students reduce MPA and improve PR from the perspective of PAA.

Although the above issues cannot be ignored, this study illustrates the timeliness of PAA to improve MPA and PR from the perspective of rare longitudinal follow-up. Meanwhile, we will continue to follow up and collect longitudinal outcomes and other exploratory indicators for inclusion in analyses in future studies. Based on the current results, we will continue to improve the reliability and rigor of the study. We hope to provide college students with effective tools to improve problem behaviors and promote mental health.

Conclusion

(1) Improving PAA is not only effective in alleviating MPA in college students, but also in increasing PR levels. (2) Elevated PR levels also have an inhibitory effect on MPA, and elevated PR leads to a more significant effect of PAA. (3) PAA can provide a stable negative prediction of MPA and a positive prediction of PR in college students.

Data availability

Data is available on reasonable request. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Hogan, J. N., Heyman, R. E. & Smith Slep, A. M. A meta-review of screening and treatment of electronic addictions. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 113, 102468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2024.102468 (2024).

Lai, X. et al. Risk and protective factors associated with smartphone addiction and phubbing behavior among college students in China. Psychol. Rep. 126, 2172–2190. https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941221084905 (2023).

Peng, Y. et al. Perceived stress and mobile phone addiction among college students during the 2019 coronavirus disease: The mediating roles of rumination and the moderating role of self-control. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 185, 111222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111222 (2022).

El-Gazar, H. E. et al. Does internet addiction affect the level of emotional intelligence among nursing students? A cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 23, 555. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-02191-6 (2024).

Lyu, C., Cao, Z. & Jiao, Z. Changes in Chinese college students’ mobile phone addiction over recent decade: The perspective of cross-temporal meta-analysis. Heliyon 10, e32327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e32327 (2024).

Zhang, C., Hao, J., Liu, Y., Cui, J. & Yu, H. Associations between online learning, smartphone addiction problems, and psychological symptoms in Chinese college students after the covid-19 pandemic. Front. Public. Health 10, 881074. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.881074 (2022).

Smith, P. J. & Merwin, R. M. The role of exercise in management of mental health disorders: An integrative review. Annu. Rev. Med. 72, 45–62. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-060619-022943 (2021).

Keynejad, R., Spagnolo, J. & Thornicroft, G. WHO mental health gap action programme (mhGAP) intervention guide: Updated systematic review on evidence and impact. Evid. Based Ment. Health 24, 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2021-300254 (2021).

Castro-Sánchez, M. et al. Physical activity in natural environments is associated with motivational climate and the prevention of harmful habits: Structural equation analysis. 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01113 (2019).

W. Pylyshyn, Z. Mental imagery: In search of a theory. Behav. Brain Sci. 25, 157–182. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0140525x02000043 (2002). discussion 182–237.

Troy, A. S. et al. Psychological resilience: An Affect-Regulation framework. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 74, 547–576. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-020122-041854 (2023).

Salmon, P. Effects of physical exercise on anxiety, depression, and sensitivity to stress: a unifying theory. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 21, 33–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00032-x (2001).

Nowacka-Chmielewska, M. et al. Running from stress: Neurobiological mechanisms of Exercise-Induced stress resilience. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232113348 (2022).

Wu, W., Carroll, I. A. & Chen, P. Y. A single-level random-effects cross-lagged panel model for longitudinal mediation analysis. Behav. Res. Methods. 50, 2111–2124. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-017-0979-2 (2018).

Liu, W., Zhou, C. & Sun, J. Effect of outdoor sport motivation on sport adherence in Adolescents—The mediating mechanism of sport atmosphere. China Sport Sci. 31, 41–47. https://doi.org/10.16469/j.css.2011.10.006 (2011).

Li, Y., Xu, J., Zhang, X. & Chen, G. The relationship between exercise commitment and college students’ exercise adherence: The chained mediating role of exercise atmosphere and exercise self-efficacy. Acta. Psychol. 246, 104253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104253 (2024).

Hu, Y. & Gan, Y. Development and psychometric validity of the resilience scale for Chinese adolescents. Acta Physiol. Sin. 902–912 (2008).

Lau, W. K. W. The role of resilience in depression and anxiety symptoms: A three-wave cross-lagged study. Stress Health 38, 804–812. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.3136 (2022).

Li, X., Feng, X., Xiao, W. & Zhou, H. Loneliness and mobile phone addiction among Chinese college students: The mediating roles of boredom proneness and Self-Control. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 14, 687–694. https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.S315879 (2021).

Feng, Z. et al. Mobile phone addiction and depression among Chinese medical students: The mediating role of sleep quality and the moderating role of peer relationships. BMC Psychiatry 22, 567. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04183-9 (2022).

Hamaker, E. L. The within-between dispute in cross-lagged panel research and how to move forward. Psychol. Methods. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000600 (2023).

Andersen, H. K. Equivalent approaches to dealing with unobserved heterogeneity in cross-lagged panel models? Investigating the benefits and drawbacks of the latent curve model with structured residuals and the random intercept cross-lagged panel model. Psychol. Methods. 27, 730–751. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000285 (2022).

Tobias, S. & Carlson, J. E. Brief report: Bartlett’s test of sphericity and chance findings in factor analysis. Multivar. Behav. Res. 4, 375–377. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr0403_8 (1969).

Johnston, M. G. & Faulkner, C. A bootstrap approach is a superior statistical method for the comparison of non-normal data with differing variances. New Phytol. 230, 23–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17159 (2021).

Falkenström, F. Time-lagged panel models in psychotherapy process and mechanisms of change research: Methodological challenges and advances. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 110, 102435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2024.102435 (2024).

Fang, J., Wen, Z., Ouyang, J. & Cai, B. A review of methodological research on moderation effects in China’s Mainland. 30, 1703–1714, (2022). https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1042.2022.01703

Eisma, M. C., Buyukcan-Tetik, A. & Boelen, P. A. Reciprocal relations of worry, rumination, and psychopathology symptoms after loss: A prospective cohort study. Behav. Ther. 53, 793–806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2022.01.001 (2022).

Zhou, X., Yang, F., Chen, Y. & Gao, Y. The correlation between mobile phone addiction and procrastination in students: A meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 346, 317–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.11.020 (2024).

Poskotinova, L. V., Krivonogova, O. V. & Zaborsky, O. S. Cardiovascular response to physical exercise and the risk of internet addiction in 15-16-year-old adolescents. J. Behav. Addict. 10, 347–351. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2021.00021 (2021).

Ye, X. L., Zhang, W. & Zhao, F. F. Depression and internet addiction among adolescents:a meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 326, 115311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115311 (2023).

Liu, M., Shi, B. & Gao, X. The way to relieve college students’ academic stress: The influence mechanism of sports interest and sports atmosphere. BMC Psychol. 12, 327. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01819-1 (2024).

Walsh, R. Lifestyle and mental health. Am. Psychol. 66, 579–592. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021769 (2011).

Fan, J., Huang, Y., Yang, F., Cheng, Y. & Yu, J. Psychological health status of Chinese college students: based on psychological resilience dynamic system model. Front. Public. Health. 12, 1382217. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1382217 (2024).

Wu, Y. et al. Psychological resilience and positive coping styles among Chinese undergraduate students: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00444-y (2020).

Xiao, W. et al. The relationship between physical activity and mobile phone addiction among adolescents and young adults: systematic review and Meta-analysis of observational studies. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 8, e41606. https://doi.org/10.2196/41606 (2022).

Sinval, J., Oliveira, P., Novais, F., Almeida, C. M. & Telles-Correia, D. Exploring the impact of depression, anxiety, stress, academic engagement, and dropout intention on medical students’ academic performance: A prospective study. J. Affect. Disord. 368, 665–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2024.09.116 (2025).

Zeng, M. et al. The relationship between physical exercise and mobile phone addiction among Chinese college students: Testing mediation and moderation effects. Front. Psychol. 13, 1000109. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1000109 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Social support and physical activity in college and college students: A meta-analysis. Health Educ. Behav. 51, 533–543. https://doi.org/10.1177/10901981231216735 (2024).

Mao, L., Li, P., Wu, Y., Luo, L. & Hu, M. The effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions for ruminative thinking: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Affect. Disord. 321, 83–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.10.022 (2023).

Stanton, R. & Reaburn, P. Exercise and the treatment of depression: A review of the exercise program variables. J. Sci. Med. Sport 17, 177–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2013.03.010 (2014).

Tong, W. & Meng, S. Effects of physical activity on mobile phone addiction among college students: The Chain-Based mediating role of negative emotion and E-Health literacy. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 16, 3647–3657. https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.S419799 (2023).

Choi, K. W. et al. Assessment of bidirectional relationships between physical activity and depression among adults: A 2-Sample Mendelian randomization study. JAMA Psychiatry 76, 399–408. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4175 (2019).

Fujiwara, H. et al. Life habits and mental health: Behavioural addiction, health benefits of daily habits, and the reward system. Front. Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.813507 (2022).

Lissak, G. Adverse physiological and psychological effects of screen time on children and adolescents: Literature review and case study. Environ. Res. 164, 149–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2018.01.015 (2018).

Ma, A. et al. Adolescent resilience and mobile phone addiction in Henan Province of China: Impacts of chain mediating, coping style. PloS One 17, e0278182. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278182 (2022).

Li, J. The relationship between peer support and sleep quality among Chinese college students: The mediating role of physical exercise atmosphere and the moderating effect of eHealth literacy. Front. Psychol. 15, 1422026. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1422026 (2024).

Lu, G. L. et al. The correlation between mobile phone addiction and coping style among Chinese adolescents: A meta-analysis. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-021-00413-2 (2021).

Yao, L. et al. Longitudinal associations between healthy eating habits, resilience, insomnia, and internet addiction in Chinese college students: A cross-lagged panel analysis. Nutrients. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16152470 (2024).

Duc, T. Q. et al. Growing propensity of internet addiction among Asian college students: Meta-analysis of pooled prevalence from 39 studies with over 50,000 participants. Public. Health 227, 250–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2023.11.040 (2024).

Yan, Y., Qin, X., Liu, L., Zhang, W. & Li, B. Effects of exercise interventions on internet addiction among college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Addict. Behav. 160, 108159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2024.108159 (2025).

Zhang, M. et al. Network meta-analysis of the effectiveness of different interventions for internet addiction in college students. J. Affect. Disord. 363, 26–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2024.07.032 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. Effects of different interventions on internet addiction: A meta-analysis of random controlled trials. J. Affect. Disord. 313, 56–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.06.013 (2022).

Pirwani, N. & Szabo, A. Could physical activity alleviate smartphone addiction in college students? A systematic literature review. Prev. Med. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2024.102744 (2024).

Funding

This study was supported by (1) Tsinghua University Initiative Scientific Research Program (grant no. 2021THZWJC15), (2) National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31971095), (3) Postgraduate Scholarship of Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.D. conceived, designed the study, performed the data analysis. Z.B. and Y.L. wrote the Chinese manuscript and wrote and supplemented the English manuscript. S.J. participated in the manuscript revision. Y.L. and J.L. participated in the data collection and collation. J.L. and J.L. are responsible for data search and literature collection. All of the authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, F., Bu, Z., Jiang, S. et al. Cross-lagged panel relationship between physical activity atmosphere, psychological resilience and mobile phone addiction on college students. Sci Rep 15, 16599 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97848-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97848-w