Abstract

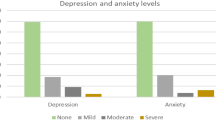

This study aims to assess the levels of anxiety and depression among healthcare workers two years post COVID-19 infection and to validate the reliability and validity of the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scales in this population. This cross-sectional study was conducted in June 2024 using a simple random sampling approach to survey healthcare institution workers. A total of 1038 valid samples were collected, and anxiety and depression levels were assessed using the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scales. Participants included healthcare workers such as doctors, nurses, administrative staff, and students. Data analysis included descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, univariate, and multivariate analyses to explore the effects of variables such as occupation and gender on anxiety and depression. Long COVID was reported in 50.8% of participants. Occupational categories significantly influenced anxiety and depression levels: compared to students (reference group), doctors, nurses, and administrative staff exhibited significantly lower scores. Non-long COVID participants showed significantly lower anxiety and depression scores than those with long COVID. Additionally, the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scales demonstrated high reliability and validity among COVID-19 population. Two years after COVID-19 infection, anxiety and depression levels among healthcare institution workers remain significantly influenced by occupational category and long COVID status. For healthcare workers, particularly those with long COVID and student groups, policymakers and healthcare administrators should consider optimizing mental health support systems. This includes implementing regular mental health screenings, providing personalized psychological interventions, offering counseling services, reducing work-related stress, and promoting the use of mental health assessment tools to improve the psychological well-being of this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the outbreak of the SARS-CoV-2 virus at the end of 2019, COVID-19 has rapidly evolved into a global pandemic, significantly impacting public health systems worldwide1. Although vaccination and public health interventions have, to some extent, reduced the number of acute infection cases, numerous studies have shown that some individuals continue to experience a variety of physical and psychological symptoms after recovery. This condition is referred to as Long COVID or Post-COVID-19 Syndrome2. Long COVID is typically defined as the persistence of multi-system symptoms for more than 12 weeks following infection with SARS-CoV-2, which cannot be explained by other established diagnoses. The range of symptoms is broad, with over 200 reported, including fatigue, shortness of breath, brain fog, depression, and anxiety, among others3. This diversity reflects the syndrome’s impact on multiple organ systems, potentially involving direct viral damage, immune dysregulation, chronic inflammation, or psychological stress, among other mechanisms4.

In recent years, the relationship between COVID-19 infection and mental health issues has garnered widespread attention. Research indicates that, compared to uninfected individuals, those who have contracted COVID-19 are more prone to psychological problems such as anxiety, depression, and insomnia, with mental health issues being particularly prominent in Long COVID patients. The prevalence of anxiety and depression in these individuals is significantly higher than in the general population5. Particularly among healthcare workers, who form the core group on the front lines of the pandemic, there has been immense physical and psychological strain. They have been exposed to infection risks, high-intensity workloads, strained medical resources, and high public and patient expectations. These factors collectively contribute to higher levels of anxiety and depression among healthcare workers6,7. Studies have shown that approximately 40% of healthcare workers exhibited significant anxiety symptoms during the pandemic, and over 30% experienced varying degrees of depression8. This psychological burden not only affects personal health but may also exacerbate burnout, reduce work efficiency, and potentially compromise patient safety9,10.

Anxiety and depression can impair healthcare workers’ decision-making abilities, attention, and emotional regulation, thereby impacting the quality of care and even increasing the occurrence of medical errors. Furthermore, research has found that Long COVID may exacerbate mental health issues among healthcare workers, with data showing that nearly 50% of healthcare professionals experienced prolonged anxiety and depression symptoms after contracting COVID-19, a proportion significantly higher than that seen in other Long COVID groups. However, studies on the long-term mental health effects of Long COVID on healthcare workers remain limited, and there is a lack of large-scale, systematic data globally11,12,13. Therefore, it is of great significance to assess the levels of anxiety and depression among Long COVID patients in healthcare settings, not only to provide evidence for targeted psychological interventions but also to lay a scientific foundation for long-term health management.

Although the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scales are widely used in mental health screening, research on the mental health assessment of COVID-19-infected populations, particularly healthcare workers, is still insufficient. Currently, there is a lack of systematic validation of the psychometric properties of these scales in specific contexts, particularly regarding their applicability and sensitivity in evaluating the psychological states of individuals after prolonged infection. Thus, this study aims to assess the levels of anxiety and depression in healthcare workers two years after COVID-19 infection and to validate the psychometric properties of the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scales within this population. Additionally, the study will explore potential influencing factors to gain a deeper understanding of the long-term impact of Long COVID on healthcare workers’ mental health and provide scientific evidence for future psychological interventions and management strategies.

Materials and methods

Study design

This study conducted a cross-sectional survey in June 2024, targeting healthcare institution workers, including physicians, nurses, administrative staff, and medical students. The aim was to assess their levels of depression and anxiety 2 years after COVID-19 infection. Reliability and validity analyses of the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scales were performed to evaluate their applicability and effectiveness in this specific population.

Study participants

Participants include hospital staff who contracted COVID-19 during the pandemic, encompassing physicians, nurses, administrative personnel, and medical students.

Inclusion criteria: Age ≥ 18, at least two years post-COVID-19 infection, willing to participate, and providing informed consent.

Exclusion criteria: No history of COVID-19 infection, history of severe mental illness or other conditions that may affect study results, or refusal to participate.

Sample size calculation

The sample size is calculated based on the principles of simple random sampling and incorporating the concepts of normal distribution and confidence intervals14. The results indicate that the effective sample size for this study should be at least 384 participants to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the statistical findings.

Study instruments

General Information Questionnaire: Designed based on a literature review, it includes variables such as gender, age, height, weight, occupational category, annual household income, educational level, working years, prior illnesses, and post-infection symptoms.

PHQ-9 Scale is a widely used self-report scale for assessing the severity of depressive symptoms. It consists of 9 items, each addressing different symptoms of depression. The PHQ-9 total score ranges from 0 to 27, classified into five levels: 0–4 (no depression), 5–9 (mild), 10–14 (moderate), 15–19 (moderately severe), and 20–27 (severe). Higher scores indicate greater depression severity. The scale has proven reliable and valid15.

GAD-7 Scale is a widely used self-report instrument for screening generalized anxiety disorder. It comprises 7 items, reflecting typical symptoms of GAD. The GAD-7 total score ranges from 0 to 21, classified into four levels: 0–4 (no anxiety), 5–9 (mild), 10–14 (moderate), and 15–21 (severe). Higher scores indicate greater anxiety severity. The scale has proven reliable and valid16.

Data collection

Data will be collected via electronic questionnaires distributed to eligible participants through the hospital’s internal email and network systems. Participants will voluntarily complete the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scales and submit their responses through the online platform.

Statistical analysis

Data entry and verification: All data will be entered into an Excel database and double-checked for accuracy and completeness.

Statistical software: Data analysis will be conducted using SPSS 26.0 and GraphPad Prism. The statistical methods included descriptive analysis, univariate analysis, correlation analysis, and multivariate analysis.

Reliability and validity testing: Internal consistency of the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scales will be evaluated using Cronbach’s α coefficient. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) will be conducted to verify structural validity. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s test results will confirm the suitability of the data for factor analysis, and high factor loadings will indicate good validity of the scales.

Quality control

Strict quality control measures will be implemented throughout the study design, execution, and data organization and analysis stages to ensure the quality and reliability of the research results.

Ethical considerations

This study adheres to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and follows ethical guidelines. All data are anonymized and securely stored on a protected server, accessible only to the research team. Participants were enrolled after providing informed consent and had the right to withdraw at any time without any adverse consequences. Psychological support resources were available for participants experiencing any discomfort.

Results

Study sample size

Initially, 1109 participants meeting the inclusion criteria were enrolled in the study. During data cleaning, we excluded invalid questionnaires where the completion time was less than 3 min or exceeded 30 min to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the data. Additionally, outliers that significantly deviated from the normal range were also removed. A total of 1038 valid samples were included in the statistical analysis, comprising 527 cases of Long COVID and 511 cases without Long COVID.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study population

The majority of participants were aged 18–39 years, with a predominance of females. Nurses and physicians constituted the largest proportion of the cohort. Most participants had a BMI below 24, held a bachelor’s degree, and had 0–10 years of work experience. The vast majority had no history of prior illnesses and reported neither smoking nor alcohol consumption. Detailed characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Reliability and validity testing of the scales

GAD-7 scale reliability and validity testing

Reliability analysis: The internal consistency of the GAD-7 scale was assessed using Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient. The result showed a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.905, indicating very high internal consistency. This suggests that the scale reliably measures the construct of anxiety, with the items effectively capturing the same psychological trait (anxiety).

Content validity: The content validity of the GAD-7 scale has been widely recognized and reviewed by experts. The validation of content shows that the items adequately cover the core areas of anxiety symptoms.

Construct validity: The construct validity of the GAD-7 scale was assessed through factor analysis. The KMO value was 0.926, well above the recommended threshold of 0.6, indicating that the data were suitable for factor analysis. Bartlett’s test of sphericity yielded an approximate chi-square value of 5294.942, with 36 degrees of freedom and a significance level of < 0.001, confirming that the correlation matrix significantly deviates from an identity matrix, making factor analysis applicable. Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed that the GAD-7 scale fits a single-factor model, with high factor loadings across all items. This demonstrates that the scale effectively measures the single construct of anxiety. The common factor variance showed that each item had a strong explanatory power for the extracted factor. Both the reliability and validity of the GAD-7 scale in anxiety measurement were excellent, with high internal consistency and a unidimensional factor structure consistent with theoretical expectations.

PHQ-9 scale reliability and validity testing

Reliability analysis: The PHQ-9 scale demonstrated a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.94, reflecting very high internal consistency, which indicates that the scale consistently measures depressive symptoms. This suggests that the items reliably reflect various aspects of depression.

Validity analysis

Content validity: The content validity of the PHQ-9 scale has been endorsed by experts, demonstrating that its items effectively cover the key aspects of depressive symptoms, ensuring its validity in measuring depression.

Construct validity: Factor analysis was also conducted to assess the construct validity of the PHQ-9 scale. The KMO value was 0.933, indicating that the data were suitable for factor analysis. Bartlett’s test of sphericity yielded an approximate chi-square value of 5294.942, with 36 degrees of freedom and a significance level of < 0.001, further supporting the suitability of factor analysis. PCA results showed that the PHQ-9 scale fits a single-factor model, with high factor loadings for all items, indicating that the scale effectively measures the single construct of depression. The common factor variance similarly demonstrated strong explanatory power for the items. The PHQ-9 scale showed high levels of reliability and validity, confirming that it is a reliable and valid tool for assessing depressive symptoms in the COVID population.

Univariate analysis of sociodemographic characteristics influencing anxiety

The study revealed that, overall, Sex, Occupation, Education Level, Working Years, Illness, and Marriage significantly influenced anxiety scores (P < 0.05). Among the Long COVID population, Occupation, Working Years, and Income were significant factors affecting anxiety scores (P < 0.05). Detailed results are presented in Table 2.

Univariate analysis of sociodemographic characteristics influencing depression

Overall, Occupation, Education Level, Working Years, Illness, and Marriage were significantly associated with depression scores (P < 0.05). In the Long COVID population, Occupation, Income, and Illness were significant factors influencing depression scores (P < 0.05). Detailed results are provided in Table 3.

Correlation analysis of sociodemographic characteristics with anxiety and depression

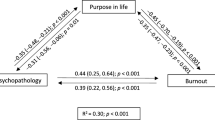

The study found a strong positive correlation between anxiety and depression, with correlation coefficients close to 0.8. In both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 populations, Occupation was significantly associated with anxiety and depression, with stronger correlations observed in the COVID-19 group (anxiety: r = 0.775, depression: r = 0.659) compared to the non-COVID-19 group. Marriage showed a weaker positive correlation with anxiety and depression in both groups. Among the non-COVID-19 population, Education Level had a higher correlation with anxiety and depression. Detailed findings are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Multivariate analysis of anxiety and depression

The results of the multivariate analysis indicated that Sex, Education Level, Income, Working Years, and Marriage had no significant impact on anxiety and depression scores. However, Occupation significantly influenced anxiety and depression levels. Compared to students (reference group), doctors, nurses, and administrative staff had significantly lower anxiety and depression scores, with the greatest reduction observed in doctors (P < 0.001). Among prior illnesses, only heart disease was associated with a significant reduction in anxiety and depression scores (P < 0.05), while other illnesses showed no significant effect. Additionally, anxiety and depression scores were significantly lower in the non-Long COVID group compared to the Long COVID group (P < 0.001). Detailed results are presented in Table 4.

Discussion

This study explored anxiety and depression levels among healthcare workers two years after COVID-19 infection, highlighting the profound impact of sociodemographic characteristics and long COVID status on mental health. Compared to studies with follow-up periods ranging from 1 week to 1 year, the 2-year timeframe of this study provides a more comprehensive perspective, allowing for a more robust assessment of the long-term psychological effects of COVID-19 infection and offering stronger scientific evidence for developing targeted mental health interventions.

Gender- and age-related differences in mental health

Our results indicate that female healthcare workers reported significantly higher anxiety and depression scores than their male counterparts, consistent with earlier studies17,18,19. Women are more prone to anxiety and depression in response to crises, potentially due to the multiple roles they assume in society, such as balancing professional responsibilities with caregiving duties20,21. Additionally, biological mechanisms, such as the influence of sex hormones on stress regulation, may increase women’s susceptibility to chronic stress22. However, no significant association between age and mental health was observed in this study. Previous research suggests that older individuals report lower anxiety and depression levels, possibly due to their more extensive coping strategies23. The lack of significance for age in our findings might be attributed to the occupational homogeneity of the study population. Healthcare workers generally exhibit high psychological resilience, and the professional experience of older individuals might mitigate the influence of age on mental health outcomes24.

Occupational differences in mental health

This study further confirms that occupational category is an important predictor of anxiety and depression25,26,27. Studies have shown that frontline nurses, who face direct patient contact, prolonged high-intensity workloads, and emotional labor burdens, are more likely to experience psychological distress, with anxiety levels significantly higher than those of doctors28. A unique finding in this study is that doctors reported lower anxiety and depression levels not only compared to nurses but also to administrative staff. This may reflect the buffering effects of higher professional status and stronger social support often associated with physicians29,30,31.

Furthermore, this study found that students exhibited the highest levels of anxiety and depression, which may be related to the uncertainty of their career development and the lack of a stable social support system11. This finding highlights that even within the specific occupational group of healthcare workers, anxiety and depression levels can vary significantly depending on different stages of career development.

The association between long COVID and mental health

Anxiety and depression levels were significantly higher in the long COVID group compared to the non-long COVID group, a finding consistent with recent literature32. Studies have highlighted that fatigue, cognitive impairments, and persistent symptoms among long COVID population substantially increase their psychological burden. Chronic fatigue, in particular, is recognized as a critical driver of anxiety and depression, as it undermines patients’ social functioning and quality of life12,19,33,34. Our study further revealed that this impact is more pronounced among healthcare workers. This heightened effect may be due to their greater awareness of health status, which amplifies concerns about professional competency and anxiety over fulfilling social roles when coping with long COVID. Future research should further explore mental health interventions for healthcare workers with long COVID, such as psychological counseling and stress management training.

The association between preexisting illness and mental health

Unlike some previous studies, this study did not find a significant association between specific preexisting illnesses and mental health35,36,37. The only exception was that individuals with heart disease exhibited lower levels of anxiety and depression. This phenomenon warrants further investigation, and potential explanations include: (1) the long-term management of chronic diseases may help patients develop stronger coping strategies and psychological resilience;38,39 (2) healthcare workers may have a better understanding of health risks and more effective disease management, which could mitigate the impact of illness on mental health32. Additionally, this study did not observe a significant association between income and mental health. This may be attributed to the relatively high overall income level among healthcare workers, which could attenuate the influence of income on mental health within this specific occupational group40,41.

The influence of culture and occupational environment on mental health

Although this study provides important insights into the mental health of healthcare workers, cultural factors must also be considered. In the context of Chinese culture, the social stigma surrounding mental illness may influence individuals’ self-assessment of anxiety and depression symptoms, potentially leading to an underestimation of mental health conditions42. Moreover, workplace environment, institutional culture, and occupational stress among healthcare workers may contribute to varying levels of anxiety and depression43,44. Differences in mental health awareness, support systems, and working conditions across countries or regions may lead to variations in anxiety and depression levels, limiting the global applicability of this study45. Future research should further explore the impact of cultural and occupational environmental factors on mental health to enhance the external validity of related findings.

Practical implications and policy recommendations

This study highlights the critical importance of mental health among healthcare workers, particularly in the context of disaster response and the prolonged impact of the pandemic. Anxiety and depression not only affect individual well-being but may also reduce work efficiency and increase the risk of medical errors46. Therefore, healthcare institutions should establish routine mental health screening mechanisms, with a particular focus on high-risk groups, to ensure early detection and intervention. Targeted psychological support, including counseling, group therapy, and stress management training, should be provided, with personalized interventions specifically designed for healthcare workers affected by long COVID. Additionally, optimizing the work environment, ensuring reasonable work schedules, and mitigating occupational burnout are essential. Establishing a comprehensive social support system can further enhance healthcare workers’ sense of belonging and psychological resilience47,48,49. At the policy level, it is recommended that mental health resources be strengthened and integrated into the management framework of healthcare institutions to ensure sustainable implementation. These measures will not only improve the mental well-being of healthcare workers but also enhance the stability and resilience of the healthcare system as a whole50.

Limitations

First, the cross-sectional design constrains causal inference, underscoring the need for longitudinal studies to delineate the trajectory of mental health changes over time. Second, self-reported assessments may be susceptible to social desirability bias, particularly in cultural contexts with pronounced mental illness stigma. This could lead participants to underreport or conceal symptoms, potentially compromising measurement accuracy. Moreover, as this study was conducted among healthcare professionals in China, the generalizability of the findings may be limited by geographic and occupational factors. Future research should broaden the study population to encompass diverse regions and healthcare systems while further examining the influence of cultural factors on mental health assessment and psychological well-being in professional groups. Such efforts would enhance the external validity and applicability of the findings.

Conclusions

This study uncovers the complex interplay of occupational roles, long COVID status, and other factors influencing anxiety and depression among healthcare workers after COVID-19 infection. The findings underscore the importance of delivering targeted psychological interventions for this vulnerable group. By deepening the understanding of mental health mechanisms, this study provides critical insights to inform post-pandemic mental health management policies. Future long-term follow-up studies should be conducted to further explore the dynamic changes in anxiety and depression levels and their influencing factors.

Data availability

Data availability statement: All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. Also, for further information please contact corresponding author.

References

Xiang, Y. T. et al. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry. 7 (3), 228–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30046-8 (2020).

Bo, H. X. et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and attitude toward crisis mental health services among clinically stable patients with COVID-19 in China. Psychol. Med. 51 (6), 1052–1053. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720000999 (2021).

Brodin, P. et al. Studying severe long COVID to understand post-infectious disorders beyond COVID-19. Nat. Med. 28 (5), 879–882. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01766-7 (2022).

Davis, H. E., McCorkell, L., Vogel, J. M., Topol, E. J. & Long, C. O. V. I. D. Major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21 (3), 133–146. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-022-00846-2 (2023).

Davis, H. E. et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. eClinicalMedicine 38, 101019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101019 (2021).

Aebischer, O., Weilenmann, S., Gachoud, D., Méan, M. & Spiller, T. R. Physical and psychological health of medical students involved in the COVID-19 response in Switzerland. Swiss. Med. Wkly. 150 (4950), w20418. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2020.20418 (2020).

Elkholy, H. et al. Mental health of frontline healthcare workers exposed to COVID-19 in Egypt: A call for action. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 67 (5), 522–531. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020960192 (2021).

Kovvuri, M., Wang, Y. H., Srinivasan, V., Graf, T. & Samraj, R. 104: psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers. Crit. Care Med. 49 (1), 36–36. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ccm.0000726304.73944.29 (2021).

Vindegaard, N. & Benros, M. E. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: systematic review of the current evidence. Brain. Behav. Immun. 89, 531–542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048 (2020).

Xiong, N., Fritzsche, K., Pan, Y., Löhlein, J. & Leonhart, R. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on Chinese healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 57 (8), 1515–1529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-022-02264-4 (2022).

Sartorão Filho, C. I. et al. Impact of Covid-19 pandemic on mental health of medical students: A cross-sectional study using GAD-7 and PHQ-9 questionnaires. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.24.20138925 (2020).

Korantzopoulos, P. et al. Depression and anxiety in Greek heart failure patients who received a cardiac resynchronization therapy device and did not receive shock therapy during a 12-month follow-up. Europace. 26 (Supplement_1), euae102483. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euae102.483 (2024).

Saunders, R. et al. Measurement invariance of the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 across males and females seeking treatment for common mental health disorders. BMC Psychiatry. 23 (1), 298. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04804-x (2023).

Cai, S., Qin, Y., Rao, J. N. K. & Winiszewska, M. Empirical likelihood confidence intervals under imputation for missing survey data from stratified simple random sampling. Can. J. Stat. 47 (2), 281–301. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjs.11493 (2019).

Shaikh, S., Munawar, L., Shakoor, S. & Siddiqui, R. Gender distribution of depression among undergraduate medical students by using PHQ-9 scale. J. Bahria Univ. Med. Dent. Coll. 09 (02), 102–104. https://doi.org/10.51985/JBUMDC2018095 (2019).

Sun, J., Liang, K., Chi, X. & Chen, S. Psychometric properties of the generalized anxiety disorder Scale-7 item (GAD-7) in a large sample of Chinese adolescents. Healthcare. 9 (12), 1709. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9121709 (2021).

Islam, M., George, P., Sankaran, S., Su Hui, J. L. & Kit, T. Impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers in different regions of the world. BJPsych Open. 7 (S1), S258–S259. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.690 (2021).

Kisely, S. et al. Occurrence, prevention, and management of the psychological effects of emerging virus outbreaks on healthcare workers: rapid review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 5, m1642. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1642 (2020).

Al Houri, H. N. et al. Stress, depression, anxiety, and quality of life among the healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic in Syria: a multi-center study. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry. 22 (1), 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-023-00470-1 (2023).

Prowse, R. et al. Coping with the COVID-19 pandemic: examining gender differences in stress and mental health among university students. Front. Psychiatry. 12, 650759. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.650759 (2021).

Graves, B. S., Hall, M. E., Dias-Karch, C., Haischer, M. H. & Apter, C. Gender differences in perceived stress and coping among college students. Dalby AR, ed. PLoS One. 16(8), e0255634. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255634 (2021).

Matud, M., Díaz, A., Bethencourt, J. & Ibáñez, I. Stress and psychological distress in emerging adulthood: A gender analysis. JCM. 9 (9), 2859. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9092859 (2020).

Vahia, I. V., Jeste, D. V. & Reynolds, C. F. Older adults and the mental health effects of COVID-19. JAMA. 324 (22), 2253. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.21753 (2020).

Marcolongo, F. et al. The role of resilience and coping among Italian healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. La. Med. Del. Lavoro Work Environ. Health. 112 (6), 496–505. https://doi.org/10.23749/mdl.v112i6.12285 (2021).

Hallgren, M. et al. Associations of sedentary behavior in leisure and occupational contexts with symptoms of depression and anxiety. Prev. Med. 133, 106021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106021 (2020).

Aly, H. M., Nemr, N. A., Kishk, R. M. & Elsaid, N. M. A. B. Stress, anxiety and depression among healthcare workers facing COVID-19 pandemic in Egypt: a cross-sectional online-based study. BMJ Open. 11 (4), e045281. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045281 (2021).

Bianchi, R. & Schonfeld, I. S. The occupational depression inventory: A new tool for clinicians and epidemiologists. J. Psychosom. Res. 138, 110249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110249 (2020).

Umbetkulova, S., Kanderzhanova, A., Foster, F., Stolyarova, V. & Cobb-Zygadlo, D. Mental health changes in healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Eval. Health Prof. 47 (1), 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/01632787231165076 (2024).

Pandey, U. et al. Anxiety, depression and behavioural changes in junior doctors and medical students associated with the coronavirus pandemic: A cross-sectional survey. J. Obstet. Gynecol. India. 71 (1), 33–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-020-01366-w (2021).

Rizk, D. N. & Abo Ghanima, M. Anxiety and depression among vaccinated anesthesia and intensive care Doctors during COVID-19 pandemic in united Arab Emirates: a cross-sectional study. Middle East. Curr. Psychiatry. 29 (1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-022-00179-z (2022).

Kolushev, I. et al. Ageism, aging anxiety, and death and dying anxiety among doctors and nurses. Rejuven. Res. 24 (5), 366–374. https://doi.org/10.1089/rej.2020.2385 (2021).

Dempsey, B., Madan, I., Stevelink, S. A. M. & Lamb, D. Long COVID among healthcare workers: a narrative review of definitions, prevalence, symptoms, risk factors and impacts. Br. Med. Bull.. 25, ldae008. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldae008 (2024).

Budzyńska, N. & Moryś, J. Anxiety and depression levels and coping strategies among polish healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. IJERPH. 20 (4), 3319. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043319 (2023).

Nguyen, O. T., Merlo, L. J., Meese, K. A., Turner, K. & Alishahi Tabriz, A. Anxiety and depression risk among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from the US census household pulse survey. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 38 (2), 558–561. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07978-4 (2023).

Livneh, H. Eight key areas in need of In-Depth examination in the field of psychosocial adaptation to chronic illness and disability. Rehabil.Couns. Educ. J. 12 (2). https://doi.org/10.52017/001c.74780 (2023).

Livneh, H. The use of generic avoidant coping scales for psychosocial adaptation to chronic illness and disability: A systematic review. Health Psychol. Open. 6 (2), 205510291989139. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055102919891396 (2019).

Livneh, H., McMahon, B. T. & Rumrill, P. D. The duality of human experience: perspectives from psychosocial adaptation to chronic illness and Disability—Empirical observations and conceptual issues. Rehabilitation Couns. Bull. 62 (2), 78–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034355218800802 (2019).

Craig, L. S. et al. Multimorbidity patterns and health-related quality of life in Jamaican adults: a cross sectional study exploring potential pathways. Front. Med. 10, 1094280. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2023.1094280 (2023).

Gebresillassie, B. M. & Kassaw, A. T. Exploring the impact of medication regimen complexity on health-related quality of life in patients with multimorbidity. Iqhrammullah M, ed. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2023, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/1744472 (2023).

Ridley, M., Rao, G., Schilbach, F. & Patel, V. Poverty, depression, and anxiety: causal evidence and mechanisms. Science 370 (6522), eaay0214. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aay0214 (2020).

Rudenstine, S. et al. Depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic in an urban, Low‐Income public university sample. J. Trauma. Stress. 34 (1), 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22600 (2021).

Zheng, M. Fighting stigma and discrimination against COVID-19 in China. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 29 (2), 135–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2022.10.032 (2023).

Che, L., Ma, S., Zhang, Y. L. & Huang, Y. Burnout among Chinese anesthesiologists after the COVID-19 pandemic peak: A National survey. Anesth. Analg. 137 (2), 392–398. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000006298 (2023).

Tan, B. Y. Q. et al. Burnout and associated factors among health care workers in Singapore during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 21 (12), 1751–1758e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2020.09.035 (2020).

Kim, S. et al. Psychosocial alterations during the COVID-19 pandemic and the global burden of anxiety and major depressive disorders in adolescents, 1990–2021: challenges in mental health amid socioeconomic disparities. World J. Pediatr. 20 (10), 1003–1016. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-024-00837-8 (2024).

Dutta, A., Sharma, A., Torres-Castro, R., Pachori, H. & Mishra, S. Mental health outcomes among health-care workers dealing with COVID-19/severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian J. Psychiatry. 63 (4), 335–347. https://doi.org/10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_1029_20 (2021).

Sheikhbardsiri, H., Tavan, A., Afshar, P. J., Salahi, S. & Heidari-Jamebozorgi, M. Investigating the burden of disease dimensions (time-dependent, developmental, physical, social and emotional) among family caregivers with COVID-19 patients in Iran. BMC Prim. Care. 23 (1), 165. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-022-01772-1 (2022).

Hadian, M., Jabbari, A., Abdollahi, M., Hosseini, E. & Sheikhbardsiri, H. Explore pre-hospital emergency challenges in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic: A quality content analysis in the Iranian context. Front. Public. Health. 10, 864019. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.864019 (2022).

Farokhzadian, J., Mangolian Shahrbabaki, P., Farahmandnia, H., Taskiran Eskici, G. & Soltani Goki, F. Nurses’ challenges for disaster response: a qualitative study. BMC Emerg. Med. 24 (1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-023-00921-8 (2024).

Søvold, L. E. et al. Prioritizing the mental health and Well-Being of healthcare workers: an urgent global public health priority. Front. Public. Health. 9, 679397. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.679397 (2021).

Acknowledgements

Lin Zhang and Jingli Wen designed the study and performed the statistical analysis. Ling Yuan contributed to data collection and interpretation. Youde Yan and Zhenjiang Zhang provided critical guidance throughout the project and were responsible for overall supervision. Kai Li assisted in manuscript preparation and revisions. Zuoling Tang contributed to the acquisition of data and provided technical support.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by Suqian Sci&Tech Program: Grant No.SY202215.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Z. and J.W. designed the study and performed the statistical analysis. L.Y. contributed to data collection and interpretation. Y.Y. and Z.Z. provided critical guidance throughout the project and were responsible for overall supervision. K.L. assisted in manuscript preparation and revisions. Z.T. contributed to the acquisition of data and provided technical support. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to participate

All participants involved in this study provided informed consent prior to their inclusion. Participants were thoroughly informed about the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. Participation was voluntary, and individuals were assured that they could withdraw from the study at any time without any consequences. Confidentiality of personal information was maintained throughout the research process, in compliance with relevant ethical guidelines.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Affiliated Suqian First People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (Ethics Approval Number: 2024-SL-0046).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, L., Wen, J., Yuan, L. et al. Anxiety and depression in healthcare workers 2 years after COVID-19 infection and scale validation. Sci Rep 15, 13893 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98515-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98515-w