Abstract

The use of molecular complexes in improving the transport properties of active layer materials for organic solar cells has been enormous in the recent era. The current study focuses on the transport and optical properties of dithiocarbonate-based complexes on Tin sulphide/Cobalt sulphide heterostructure. The charge transfer properties show electronegativity features for the N-butylamine complex, whereas electropositive transport features are observed for the N-dodecyl amine and mixed (N-butylamine/N-dodecylamine) complex blend. This charge transfer behaviour is consistent with typical acceptor–donor features, which are associated with metal-thiocarbamate complex transport. The optical features for dithiocarbonate-based complexes supported metal sulphide heterostructure show increased absorption and reflective plasmonic features in comparison with pristine metal sulphide heterostructure. The study proposes the incorporation of a dithiocarbonate complex as support for metal sulphide heterostructure active layer material that can be used to drive improved charge transport and localized surface plasmon resonance, which is crucial for charge transport in organic solar cell devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The potential of bimetallic sulphide-based active layer materials for organic solar cell (OSC) applications has experienced rapid growth recently. This growth, as evidenced in numerous research studies and ongoing laboratory testing towards commercialization, can be attributed to the excellent charge transfer properties of OSC1,2. The charge transfer features of metal sulphides have demonstrated suppression of charge recombination in OSCs3, which is crucial for improving the overall performance of the fabricated device. The charge transfer properties of bimetallic sulphide heterostructures have shown the potential for metal–metal charge transfer, with the incorporation of ligands supporting metal–ligand transport features4. The flexibility of tuning the transport properties of bimetallic sulphides enables its applicability to different applications such as catalysis, water splitting and quantum dots OSCs5,6. The potential of SnS nanomaterials for OSC applications has been demonstrated; however, experimental implementation of standalone SnS as an active layer material has proven to be low7. However, CoS has a narrow band gap and has the potential to improve the conductivity of SnS. Hence, bimetallic SnS/CoS has the potential for improved parent material for the OSC active layer.

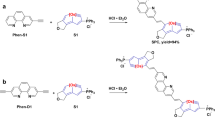

While molecular complexes such as carbon-based ligands have demonstrated enormous potential in tuning the optical response and transport properties of bimetallic sulphide heterostructures, dithiocarbamate complexes can extend the frontiers of their properties8,9. The use of dithiocarbamate has demonstrated potential for halide perovskites10,11 and other OSC types. A recent instance showed the potential of optimizing bimetallic sulfide heterostructures using dithiocarbamate complexes for improved quantum dots-based dye-sensitized solar cells12. Dithiocarbamate complexes such as N-butylamine and N-dodecylamine have proven effective in improving active site interactions through anionic interaction transport activities13. Dithiocarbamate complexes are a class of monoanionic 1,1-dithiolate ligands which comprise ligand chains like xanthates, carbamates, and dithiophosphates14. The dithiocarbamate complex can act as a reducing agent for bimetallic sulphides and aid charge transport properties, especially for light-matter interaction-based applications.

Moreover, there have been studies covering the experimental implementation of bimetallic/dithiocarbamate heterostructure for organic solar cells15,16. However, probing the charge transport mechanism and optical response using first principles approaches is lacking. First principles approaches can elucidate the charge donor/acceptor mechanism that are the backbone of charge recombination and performance of OSCs. Therefore, understanding the charge transport mechanism of dithiocarbamate-based OSCs using a first-principles approach can enable the optimization of OSC devices for the future advancement of PV technology. The current study focuses on examining the effect of N-butylamine and N-dodecylamine complexes on the electronic charge transfer and optical response of SnS/CoS heterostructure towards organic solar cell application using density functional theory approaches.

Computational details

The charge transfer and optical response properties of pristine bimetallic SnS/CoS and dithiocarbamate-supported SnS/CoS heterostructures were examined using the first principles approach in the Kohn–Sham formalism of the Cambridge Serial Total Energy Package (CASTEP) code17. The exchange–correlation effect of the electron–electron interactions as well as the valence-cores interaction was described using the generalized gradient approximation and Vanderbilt ultrasoft pseudopotentials18,19, respectively. The bimetallic SnS/CoS heterostructure was constructed from combined triclinic unit cells of SnS and CoS monolayers, with lattice parameters a = 3.95 Å, b = 4.53 Å, c = 11.39 Å and a = b = 3.62 Å, c = 5.01 Å, respectively. Preceding the formation of the heterostructure, the band gap of the SnS monolayer of 1.1 eV was benchmarked with proximal experimental value (1.3 eV)20, whereas CoS monolayer showed metallic features, which aligns with a narrow band gap of (0.00 eV) in previous reports21,22.

A \(2\times 1\) supercell comprising mono layers of both SnS and CoS was constructed to form the pristine SnS/CoS heterostructure. The unit cell of either of N-butylamine or N-dodecylamine complex was expanded two folds (\(2\times 2\)), while the mixed complex configuration (N-butylamine/N-dodecylamine) was constructed using the blend tool of Material Studio. Each of these complexes were separately incorporated into the SnS/CoS heterostructure, and geometry optimization was achieved using converged plane-wave cutoff energy of 300 eV and 1 × 2 × 2 k-point sampling corresponding to custom fine quality-ultrasoft option. The CASTEP fine quality and ultrasoft pseudo-potential option has proven efficient in converging complex heterostructures23. To further ensure an accurate representation of the ground state properties of these systems, the convergence criteria were set to a limit of 0.01 eV/Å and \({10}^{-4}\) eV for self-consistent Field forces and energy, respectively.

Results and discussions

Stability and charge transfer

The current study utilized the first-principles density functional theory approach to probe the charge transport properties and optical response of pristine and dtc-supported bimetallic SnS/CoS heterostructures. The optimized structure of the heterostructures is shown in Fig. 1 and shows similar bond lengths sampling (S2–Co4, S1–Co2 and S3–Co4) of pristine and dtc-supported bimetallic heterostructures. For instance, initial bond shrinkage (\(2.0978 \to 1.9940 \to 1.9940\) Å), (\(2.1227 \to 19935 \to 1.9935\) Å) was observed when N-dodecylamine was incorporated and stabilized with a mixed N-butylamine/N-dodecylamine blend, respectively. The minimal bond shrinkage of the dtc-supported bimetallic configurations suggests reasonable stability, which is crucial for experimental implementation.

To further support the stability of the heterostructure, cohesive energy calculation was considered. The cohesive energy given in Eq. (1) has proven effective in estimating the stability of heterostructures24.

Herein \({E}_{total}\) depicts the total energy of the dtc-supported SnS/CoS heterostructure, \({E}_{pristine}\) is the energy of the pristine bimetallic heterostructure, \({E}_{dtc}\) is the energy of the individual unit dtc complex and \({n}_{i}\) is the total number of each atomic constituent. Table 1 shows the calculated values of the cohesive energies, where the pristine bimetallic heterostructure depicts negative cohesive energies. The negative values suggest a stable heterostructure and can form spontaneously under the conventional thermodynamic equilibrium synthesis routes such as the sol–gel technique, and chemical vapour deposition, amongst others. However, the incorporation of the dtc complex renders the cohesive energies slightly positive (endothermic reaction), which can be attributed to increased defects and endothermic reactions emanating from dithiocarbonate complexes. The chemistry of C–N interaction-based dtc has been shown to feature delocalization, which could trigger ligand dissociation, decomposition, or oxidation14. While the endothermic reaction suggests the non-spontaneous formation of the dtc-based heterostructures, the use of heating or other non-equilibrium synthesis techniques can assist in the formation process. Indeed, a previous study16 was able to achieve the process by using above 280 °C heating.

The backbone for OSC performance is mainly attributed to charge transfer and recombination between the different intrinsic layers. The current study approaches the charge transfer niche using Mulliken charge population analysis25 and electron density difference. Table 1 outlines the net charge transfer for pristine and dtc-supported bimetallic heterostructure configurations. The negative charge transfer values show electronegative transport features, which suggest the majority of carriers within the bimetallic heterostructure possess potential for charge donation. The behaviour is corroborated by the Mulliken charge analysis shown in Fig. 2. The electronegative charge transfer is mainly driven by the S atoms. The inclusion of the N-butylamine complex shows a reduction in the electronegativity value. As indicated in Mulliken charge analysis, there is a decrease in net charge transfer in both Sn and S and a corresponding increase in the Co atom. The charge transfer can be attributed to metal–metal and metal-complex features26. The incorporation of N-dodecylamine and mixed complex blend shows electropositive charge transfers. The electropositive charge transfers are accompanied by an increase in net charge transfers of Co and the dtc complex components, which iterates increased metal–metal and metal-complex charge transfers.

Hence, we propose that organic solar cells based on a metal-dtc complex active layer would undergo charge transfers from both metal–metal and metal-complex features. Additionally, the complex type will determine whether the charge transfers are donor or acceptor driven.

Electron density difference was implemented to reiterate the observed charge transfer properties. As shown in Fig. 3a, there is more charge depletion (yellowish region) build-up, especially around the SnS region, which corroborates Mulliken charge behaviour discussed above. Similar features are observed for the Butylamine complex supported SnS/CoS, which suggests decreased electron density. The features change for N-dodecylamine, and the mixed blend supports charge accumulation (blueish region, see Fig. 3b–d). The charge transfer corroborates the electropositive charge transfer features, where there are donor activities towards Co atoms and dithiocarbamate complexes from Sn and S atoms.

The electron density difference colour mapping of pristine and dithiocarbamate complex supported bimetallic heterostructure. (a) Pristine SnS/CoS heterostructure, (b) N-Butylamine supported SnS/CoS heterostructure, (c) N-Dodecylamine supported SnS/CoS heterostructure and (d) mixed complex blend supported bimetallic SnS/CoS heterostructure. The yellow region represents charge depletion (electron decrease), whereas the blue region depicts charge accumulation (electron increase).

Furthermore, the isosurface colour mapping for all the electron density difference maps shows an extensive yellow region in pristine SnS/CoS heterostructure, which suggests a delocalized charge transport, hence there is high potential for charge distribution/redistribution over a wider electron region.

Electronic properties

The density of states (DOS) depicting the magnitude of quantum states per unit energy as a function of energy is a quantity that enables the probing of transport properties of a heterostructure interface. Figure 4 shows the density of states of pristine and dithiocarbamate-supported bimetallic SnS/CoS heterostructure. A comparison of pristine and N-butylamine-supported bimetallic heterostructure shows an increase in the DOS, which suggests modification of the electronic structure due to interactions between the metals, the heterostructure interface, and the dithiocarbamate ligands. The constituent of the dithiocarbamate complex like sulfur and nitrogen atoms possess electronegative features and can enable strong bond formations with metallic atoms. The bond formation with the bimetallic heterostructure with the ligand complex can induce electron donor/acceptor interactions, which can cause redistribution of the electron density between the two metals and at the ligand complex interface. A shift below the Fermi level is also observed for N-butylamine complex incorporation, which can be attributed to back bonding and state stabilization27. The back bonding interactions causes a π-donor ligand–metal interaction, which can be attributed to both a σ-symmetry electron pair and a filled orthogonal p-orbital metallic bond formation28. Additionally, the back bonding features of the electron density of the bimetallic/dtc complex can result in the stabilization of some of the unoccupied states below the Fermi level. The case of N-dodecylamine and mixed blend supported bimetallic SnS/CoS heterostructure shows a relative decrease in the DOS, which suggests steady redistribution of the electron density and possible stabilization of the unoccupied states.

The partial density of states (PDOS) provides insight into the individual orbital contribution to the total DOS of the heterostructure. Figure 5 shows the PDOS of pristine and dithiocarbamate-supported bimetallic SnS/CoS heterostructure. An increased contribution of Co 3d orbital is prominent for pristine bimetallic SnS/CoS heterostructure, which suggests the charge transport behaviour depicted in Table 1 and Fig. 2 are attributed to contributions for electrons from Sn 5p and S 3p to Co 3d. Additionally, there is minimal alignment of the unoccupied states of the orbital states, implying the charge transport behaviour of pristine bimetallic heterostructure is mainly due to back bonding and metal–metal charge transfer rather than hybridizations of the orbital states. The introduction of the N-Butylamine complex shows increased prominence of Co 3d and S 3p. While the Co 3d can be attributed to increased charge transfer resulting from metal–metal transport, the prominence of the S 3p orbital state can be attributed to increased S-atomic interactions. The significant contributions of S 3p from both metallic components are crucial in driving the intrinsic electronic transport in the heterostructure system. The case of N-Dodecylamine and mixed dithiocarbamate complex blend show a broadening of the unoccupied states below the Fermi level. The broadening of the unoccupied states can be attributed to the formation of antibonding states29. The unoccupied states from S 3p can act as a bridging ligand between two metal–metal charge transport resulting in a back-donation, where electrons from the metal’s d-orbitals are donated into the S 3p empty orbitals30. Additionally, antibonding features occur from partial overlap of the unoccupied states of Co 3d and S 3p, which suggests higher energy orbital states31. The bonding interactions between dithiocarbamate complexes and the SnS/CoS create antibonding states, which are located at the unoccupied region. The bonding interactions owing to the bonding strengths result in the unoccupied state broadening across the bimetallic heterostructure.

The partial density of states of pristine and dithiocarbamate-supported bimetallic SnS/CoS heterostructure showing the different orbital states. (a) Pristine bimetallic SnS/CoS heterostructure, (b) N-butylamine complex supported SnS/CoS heterostructure, (c) N-dodecylamine supported SnS/CoS heterostructure and (d) mixed blend supported SnS/CoS heterostructure.

Additionally, the broadening of unoccupied states resulting from the bonding interactions and coupling can lead to the delocalization of electron transport. Due to the electronegative features of the bimetallic heterostructure (see Table 1), there is a possibility of increased electron delocalization transport. This behaviour is consistent with the electron density difference isosurface distribution (see Fig. 3c and d).

Optical properties

The optical response properties offer the probing of light interaction with the bimetallic heterostructure. The optical response properties of pristine and dtc-supported bimetallic heterostructure focused on dielectric function response, optical absorption and reflectivity. Moreover, the longitudinal dielectric constant has proven effective in describing electron energy loss function \({\upvarepsilon }_{ij}\) and is estimated using the imaginary part of the loss function given as:

where \({E}_{k,c}\) and \({E}_{k,v}\) depicts the occupied and unoccupied band states, \(\Omega\) depicts the cell volume, and k represents the vector sum over the entire metal sulfide-based heterostructure configuration32. Figure 6 shows the dielectric function response properties of pristine and dtc-supported bimetallic heterostructure. The case of pristine bimetallic SnS/CoS shows dielectric plasmonic transitions at around \(0.23\) and 2.9 eV, which are attributed to surface plasmon resonance and interband transitions33. Localized plasmonic resonance (LSR) depicting streams of electronic oscillations at the surface of the bimetallic surface reflects the light matter interactions. The possibility of tuning the localized fields and resonance can lead to improvement with respect to site-selectivity34. Hence, the incorporation of the dtc complexes offer an opportunity of tuning the LSR properties of the bimetallic heterostructure. As indicated in Fig. 6, there is a decrease in the dielectric function with a shift towards lower photon energy. The downward shift is accompanied by the formation of additional plasmonic transitions at ~ 8.4 eV and 11.6 eV for N-butylamine complex. Additionally, mixed blend complex incorporation shows a decrease in the photon energy \(8.4 \to 6.88\) and \(11.6 \to 11.15\) eV. The formation of the additional plasmonic transition supports charge transport properties of the dtc-supported bimetallic sulfide heterostructure.

Optical reflectivity is a quantity that provides insights into the interface properties such as refractive index and surface roughness and can be crucial for probing the light-matter interaction of bimetallic heterostructures. Figure 7 shows the optical reflectivity response properties of pristine and dtc-supported SnS/CoS heterostructures. The case of pristine SnS/CoS heterostructure shows reflectance at 113 nm and 156 nm, which is consistent with UV wavelength reflection. The reflectance at lower wavelengths suggests electronic band transitions, such as excitonic effects and direct interband transitions, which are prominent at high energies35.

Furthermore, the photon energy corresponding to the low wavelength corresponds to \(7.75\)–\(11.27\) eV) are high and consistent with the bimetallic core-level electron states such as the S 3p, Sn 5p and Co 3d interactions. The incorporation of the dithiocarbamate complexes decreases the reflectivity at lower wavelengths except for N-dodecylamine at 156 nm, where there is a significant increase. The decrease in reflectivity owing to the dtc inclusion can be attributed to the increased absorption of energy. The increased reflectivity at a high wavelength for N-dodecyl amine can be attributed to its photoluminescence features, where increased photoemission is highly likely. Reports have suggested that the amine group component of the N-dodecylamine complex enables stabilization and increased surface plasmon resonance of analytes by acting as binding sites on the surface of the heterostructure36.

The case of the mixed blend complex incorporation shows a slight drop in reflectivity at 156 nm, which suggests the N-Dodecylamine complex has a significant effect in influencing the reflective response properties of the SnS/CoS heterostructure. The decrease in reflective response properties at low wavelength can be attributed to lower d–-d transition energies and consistent with square planar and octahedral complexes like dithiocarbamates37.

The optical absorption properties are another quantity that enables the probing of light-matter interactions at the valence and conduction band interfaces. As indicated in Fig. 8, there are similarities to the optical reflectivity properties, where the plasmonic transitions tend to absorb at lower wavelengths. The absorption of the plasmonic transition at lower UV wavelength can be attributed to interband and charge transfers as iterated in the PDOS properties. The charge transfer between SnS and CoS can modify the density of states near the Fermi level. The resulting interband transitions can enable increased surface plasmon resonance, which is crucial for optimizing the light absorption of organic solar cells. The incorporation of the dithiocarbamate complexes shows similar behaviour as depicted in the reflective properties of the SnS/CoS heterostructure. The presence of the dithiocarbamate in the SnS/CoS heterostructure enables charge transfer between the SnS/CoS bimetallic interfaces, which enables plasmonic hybridization and modes.

In comparison with experimental bimetallic-based sulfides from previous work38, there exists a variation in frequency bands, which are comparable to the observed photon energy. The variation in the optical frequencies is attributed to dielectric and exchange resonances. Hence, the optical response properties in current study offers an avenue in tuning optical performances of bimetallic sulfide heterostructure for applications such as microwave absorption and sensors39,40.

Conclusions

The current study focused on probing the charge transfer and optical response features of pristine and dithiocarbamate-supported bimetallic SnS/CoS heterostructure. The charge transfer properties show negative charge transfer values, which suggest majority of the carriers within the bimetallic heterostructure are mostly driven by charge donors. The optical properties of pristine and dithiocarbamate-supported bimetallic SnS/CoS heterostructure show absorption and reflectivity at UV wavelength regions and plasmonic transitions, which is analogous to low photon energy absorption and reflection. The optical properties depict localized field enhancement through surface polarization effects, owing to the modified localized dielectric properties. The dithiocarbamate incorporation into the SnS/CoS bimetallic heterostructures offers a route to tailoring plasmonic properties for organic solar cell applications.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Reeja-Jayan, B. & Manthiram, A. Effects of bifunctional metal sulfide interlayers on photovoltaic properties of organic–inorganic hybrid solar cells. RSC Adv. 3, 5412–5421 (2013).

Riede, M., Spoltore, D. & Leo, K. Organic solar cells—The path to commercial success. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2002653. https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.202002653 (2021).

Ahmed, A. Y. A. et al. Application of cobalt-sulphide to suppress charge recombinations in polymer solar cell. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 185, 108917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mssp.2024.108917 (2025).

Idisi, D. O., Benecha, E. M. & Meyer, E. L. Metal-ligand transport and optical properties of metal sulfide heterostructure: A density functional theory study. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 182, 108704 (2024).

Xin, Y., Kan, X., Gan, L.-Y. & Zhang, Z. Heterogeneous bimetallic phosphide/sulfide nanocomposite for efficient solar-energy-driven overall water splitting. ACS Nano 11, 10303–10312. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.7b05020 (2017).

Chinnadurai, D., Rajendiran, R. & Kandasamy, P. Bimetallic copper nickel sulfide electrocatalyst by one step chemical bath deposition for efficient and stable overall water splitting applications. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 606, 101–112 (2022).

Sinsermsuksakul, P. et al. Overcoming efficiency limitations of SnS-based solar cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 4, 1400496. https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201400496 (2014).

Sarker, J. C. & Hogarth, G. Dithiocarbamate complexes as single source precursors to nanoscale binary, ternary and quaternary metal sulfides. Chem. Rev. 121, 6057–6123. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c01183 (2021).

Zafar, A., Ahmad, K. S., Jaffri, S. B. & Sohail, M. Physical vapor deposition of SnS:PbS-dithiocarbamate chalcogenide semiconductor thin films: Elucidation of optoelectronic and electrochemical features. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 196, 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/10426507.2020.1799371 (2021).

He, J. et al. Surface chelation of cesium halide perovskite by dithiocarbamate for efficient and stable solar cells. Nat. Commun. 11, 4237. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18015-5 (2020).

Wang, T. et al. Asymmetric alkyl chain engineering for efficient and eco-friendly organic photovoltaic cells. Small 21, 2408308. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202408308 (2024).

Agoro, M. A., Meyer, E. L. & Olayiwola, O. I. Fabrication of heterostructure multilayer devices through the optimization of Bi-metal sulfides for high-performance quantum dot-sensitized solar cells. RSC Adv. 14, 33751–33763 (2024).

Ha, N. et al. Dithiocarbamate-based solution processing for cation disorder engineering in AgBiS2 solar absorber thin films. Adv. Energy Mater. 15, 2402099. https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.202402099 (2024).

Hogarth, G. Metal-dithiocarbamate complexes: Chemistry and biological activity. Mini. Rev. Med. Chem. 12, 1202–1215 (2012).

Motaung, M. P. & Onwudiwe, D. C. Metal dithiocarbamates as useful precursors to metal sulfides for application in quantum dot-sensitized solar cell. In: Sustainable Materials and Green Processing for Energy Conversion, 305–339 (Elsevier, 2022). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128228388000053 (Accessed October 31, 2024).

Agoro, M. A. & Meyer, E. L. Coating of CoS on hybrid anode electrode with enhance performance in hybrid dye-sensitized solar cells. Electrochim. Acta 502, 144877 (2024).

Clark, S. J. et al. First principles methods using CASTEP. Zeitschrift Für Kristallographie- Crystalline Materials 220, 567–570 (2005).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Vanderbilt, D. Soft self-consistent pseudopotentials in a generalized eigenvalue formalism. Phys. Rev. B 41, 7892 (1990).

Hegde, S. S., Murahari, P., Fernandes, B. J., Venkatesh, R. & Ramesh, K. Synthesis, thermal stability and structural transition of cubic SnS nanoparticles. J. Alloy. Compd. 820, 153116 (2020).

Wang, C., Pang, X., Wang, G., Gao, L. & Fu, F. Cobalt sulfide (Co9S8)-based materials with different dimensions: Properties, preparation and applications in photo/electric catalysis and energy storage. Photochem 3, 15–37 (2023).

Ma, X. et al. Three narrow band-gap semiconductors modified Z-scheme photocatalysts, Er3+:Y3Al5O12@NiGa2O4/(NiS, CoS2 or MoS2)/Bi2Sn2O7, for enhanced solar-light photocatalytic conversions of nitrite and sulfite. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 66, 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2018.05.024 (2018).

Ahmad, S., Ur Rehman, J., Tahir, M. B., Alzaid, M. & Shahzad, K. Investigation of external isotropic pressure effect on widening of bandgap, mechanical, thermodynamic, and optical properties of rubidium niobate using first-principles calculations for photocatalytic application. Opt. Quant. Electron 55, 346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11082-023-04596-0 (2023).

Hussain, G., Asghar, M., Waqas Iqbal, M., Ullah, H. & Autieri, C. Exploring the structural stability, electronic and thermal attributes of synthetic 2D materials and their heterostructures. Appl. Surface Sci. 590, 153131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.153131 (2022).

Wiberg, K. B. & Rablen, P. R. Atomic charges. J. Org. Chem. 83, 15463–15469. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.joc.8b02740 (2018).

Joy, J., Danovich, D., Kaupp, M. & Shaik, S. Covalent vs charge-shift nature of the metal-metal bond in transition metal complexes: A unified understanding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 12277–12287. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.0c03957 (2020).

Bistoni, G. et al. How π back-donation quantitatively controls the CO stretching response in classical and non-classical metal carbonyl complexes. Chem. Sci. 7, 1174–1184 (2016).

Bhattacharjee, K. & Prasad, B. L. Surface functionalization of inorganic nanoparticles with ligands: A necessary step for their utility. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 2573–2595 (2023).

Baril-Robert, F., Radtke, M. A. & Reber, C. Pressure-dependent luminescence properties of Gold(I) and Silver(I) dithiocarbamate compounds. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 2192–2197. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp206766p (2012).

Pienack, N. et al. Two pseudopolymorphic star-shaped tetranuclear Co3+ compounds with disulfide anions exhibiting two different connection modes and promising photocatalytic properties. Chem. A Eur. J. 21, 13637–13645. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201501796 (2015).

Liu, Y., McCue, A. J. & Li, D. Metal Phosphides and sulfides in heterogeneous catalysis: Electronic and geometric effects. ACS Catal. 11, 9102–9127. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.1c01718 (2021).

Idisi, D. O., Benecha, E. M. & Meyer, E. L. First-principles study of the electronic and optical properties of layered SnS2/graphene heterostructure. Mater. Sci. Eng., B 310, 117713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mseb.2024.117713 (2024).

Min, Y. & Wang, Y. Manipulating Bimetallic nanostructures with tunable localized surface plasmon resonance and their applications for sensing. Front. Chem. https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2020.00411 (2020).

Sytwu, K., Vadai, M. & Dionne, J. A. Bimetallic nanostructures: Combining plasmonic and catalytic metals for photocatalysis. Adv. Phys. X 4, 1619480. https://doi.org/10.1080/23746149.2019.1619480 (2019).

Di, J. & Jiang, W. Recent progress of low-dimensional metal sulfides photocatalysts for energy and environmental applications. Mater. Today Catal. 1, 100001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcata.2023.100001 (2023).

Liu, M., Wang, Y.-Y., Liu, Y. & Jiang, F.-L. Thermodynamic implications of the ligand exchange with alkylamines on the surface of CdSe quantum dots: The importance of ligand-ligand interactions. J. Phys. Chem. C 124, 4613–4625. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b11572 (2020).

Poirier, S., Roberts, R. J., Le, D., Leznoff, D. B. & Reber, C. Interpreting effects of structure variations induced by temperature and pressure on luminescence spectra of platinum(II) Bis(dithiocarbamate) compounds. Inorg. Chem. 54, 3728–3735. https://doi.org/10.1021/ic5025718 (2015).

Che, J. et al. Bimetallic sulfides embedded into porous carbon composites with tunable magneto-dielectric properties for lightweight biomass—reinforced microwave absorber. Ceram. Int. 49, 27094–27106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2023.05.254 (2023).

Veeralingam, S. & Badhulika, S. Bi-Metallic sulphides 1D Bi2S3 microneedles/1D RuS2 nano-rods based n-n heterojunction for large area, flexible and high-performance broadband photodetector. J. Alloy. Compd. 885, 160954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.160954 (2021).

Sahu, A. K., Mishra, M., Nayak, K. C. & Tripathy, S. K. An investigation on effect of various mono and Di-sulphide coatings on the performance of an Au–Ag bimetallic SPR sensor: An attempt towards noninvasive urine-glucose detection. Opt Quant. Electron. 56, 108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11082-023-05620-z (2023).

Acknowledgements

DOI acknowledges the Govan Mbeki Research and Development Center for funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DOI: Initial manuscript draft, Data curation and validation, Visualization, methodology, review and editing EL: Manuscript review and editing EM: data validation, Manuscript review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Idisi, D.O., Meyer, E.L. & Benecha, E.M. First-principles study of electronic and optical response properties of bimetallic-sulphide heterostructure supported dithiocarbonate complex for organic solar cells. Sci Rep 15, 13526 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98804-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98804-4