Abstract

The esophagogastric junction (EGJ) has a complex anatomy and critical physiological functions, making postoperative quality of life an important consideration in the surgical resection of gastrointestinal stromal tumors at this location (EGJ-GISTs). We conducted a propensity score-matched (1:1) analysis to compare the safety and efficacy of endoscopic resection (ER) and laparoscopic resection (LR) for patients with EGJ-GIST treated at the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, China, from December 2013 to November 2023. We reviewed 176 patients (ER 82; LR 94) with EGJ-GIST, of whom 85 patients with a tumor size of 2–5 cm met the matching criteria (ER 42; LR 43), yielding 20 pairs of patients. ER showed advantages over LR, with a shorter postoperative nil per os time (4.0 days (IQRs, 3.0–5.0) vs. 5.5 days (IQRs, 4.3–7.8), p = 0.005) and postoperative hospitalization time (6.0 days (IQRs, 5.0−6.8) vs. 8.5 days (IQRs, 6.0−11.8, p = 0.002). Long-term adverse events were significantly lower in the ER group (15% vs. 55%, p = 0.005). No recurrence or metastasis was observed in either group during a mean follow-up of 42.3 months. These findings suggest that for 2–5 cm EGJ-GISTs, ER is a safe and effective alternative, offering minimal invasiveness, faster recovery, fewer complications, and improved long-term quality of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are uncommon mesenchymal neoplasms originating from interstitial cells of cajal, primarily occurring in the stomach or small intestine1,2. Approximately 5.8–13.5% of these tumors are located at the esophagogastric junction (EGJ)3,4. The latest National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) clinical guidelines advocate complete surgical resection for all GISTs, except for very small lesions (< 2 cm) lacking high-risk endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) features.

With technological advances, laparoscopic resection (LR) has progressively emerged as the preferred surgical modality for gastric GISTs5. Laparoscopic surgery demonstrates efficacy comparable to open surgery and may yield superior short-term outcomes6. In recent years, ER has gained prominence in gastric GIST management. Studies comparing ER with surgical resection for gastric GISTs have emerged. ER is considered a viable treatment approach for small GISTs (< 5 cm)6,7. ER demonstrates comparable short-term outcomes to laparoscopic surgery, even for gastric GISTs greater than 5 cm in diameter, while offering advantages of swift postoperative recovery and cost-effectiveness8.

However, the clinical treatment options for esophagogastric junction GIST (EGJ-GIST) are rarely reported. The EGJ has complex anatomical features and plays crucial physiological roles. Dysfunction or injury of the lower esophageal sphincter at the EGJ is a major contributor to gastroesophageal reflux9. Therefore, when resecting an EGJ-GIST, physicians should ensure that not only complete tumor resection but also minimal damage to the EGJ9,10. However, LR encounters challenges in managing EGJ-GISTs, primarily because the optimal surgical approach is through the greater curvature and anterior wall of the stomach11,12. Although some studies have indicated that laparoscopic surgery does not adversely affect postoperative outcomes or long-term survival compared to open surgery, preserving the function of the EGJ, maintaining the patient’s quality of life, and minimizing long-term postoperative complications, such as GERD, remain significant challenges13. Existing research has not yet conducted comprehensive analyses of patients’ long-term postoperative quality of life13,14,15.

As a minimally invasive technique, ER theoretically minimizes disruption to the EGJ’s anatomical structure and may enhance functional preservation. Therefore, we conducted a single-center retrospective study, comparing the short-term efficacy and long-term outcomes of endoscopic and laparoscopic surgeries for EGJ-GISTs.

Methods

Study design and patients

A retrospective review was conducted on all patients who underwent endoscopic resection (ER) or laparoscopic resection (LR) for esophagogastric junction gastrointestinal stromal tumors (EGJ-GISTs) at the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, China, from December 2013 to November 2023 (Fig. 1). Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) pathological confirmation of gastrointestinal stromal tumor; (2) preoperative computed tomography (CT) and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) confirming tumor origin at the esophagogastric junction; (3) absence of metastasis to other organs; (4) tumor diameter between 2 and 5 cm. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) tumor size < 2 cm or > 5 cm; (2) treatment modalities other than ER and LR; (3) concurrent malignancies; (4) multiple metastases of GIST at the time of diagnosis; (5) preoperative neoadjuvant imatinib therapy; (6) inability to tolerate surgery; (7) surgical treatment for residual tumors in the ER group; (8) incomplete clinical data, loss to follow-up, or follow-up duration less than six months.

This study protocol has been approved by the Ethical Committee of Scientific Research and Clinical Trials of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (Approval No. 2022-KY−1236−001) and was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The data were anonymized and the study was retrospective, and the Scientific Research and Clinical Trial Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University waived the requirement of informed consent for the study subjects.

Definition of EGJ-GIST

EGJ-GIST is defined as gastric GISTs with the upper border located within 5 cm of the Esophagogastric line and esophageal GISTs with the lower border located within < 2 cm of the Esophagogastric line13,16.

Long-term adverse events are defined as unfavorable symptoms that affect patients’ quality of life, such as gastroesophageal reflux, heartburn, or anastomotic inflammation, which may persist for an extended period following gastric surgery.

Endoscopic resection

All ER procedures were performed by experienced endoscopists who have successfully and independently completed at least 200 cases of submucosal tumors in the gastrointestinal tract. ER was performed under general anesthesia and tracheal intubation after a fasting period of at least 8 h. Prophylactic intravenous antibiotics were administered 30 min before the procedure. Patients were closely monitored postoperatively.

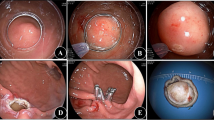

The steps for ER are as follows (Fig. 2): Marking the edge of the lesion with the endoscopic Dual knife. Local injection of saline solution along the marked points submucosally using an injection needle, with or without methylene blue injection. Incise the mucosal layer along the marked points using a Dual or Hook knife to expose the lesion. Choose Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection (ESD), Endoscopic Submucosal Excavation (ESE), or Endoscopic Full-Thickness Resection (EFTR) based on the lesion’s layer of involvement. Perform precise dissection to achieve complete tumor resection. In cases of muscularis propria injury, close the defect with metallic clips17,18. For deeper tumors, incise the serosal layer at the lesion’s base using an electrosurgical knife to ensure complete resection. Close the wound with titanium clips or nylon sutures19.

Endoscopic resection of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). (A) Endoscopic view of the GIST. (B) Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) scan of the tumor. (C) Marking the lesion margins. (D) Incision of the surrounding mucosa to expose the tumor. (E) Dissection of the serosal layer at the lesion base for complete resection. (F) Post-resection wound site. (G) Closure of the wound with titanium clips. (H) Resected specimen.

Laparoscopic resection

The specific surgical approach was determined based on the location and size of the tumor. The patient was positioned in the supine position under general anesthesia with the legs separated. A total of up to five trocars were used, depending on the surgical requirements. The first 12 mm trocar was inserted at the level of the umbilicus for laparoscopic inspection. The remaining trocars were inserted on both sides by the primary surgeon and assistant. Preoperative fiberoptic gastroscopy was performed to identify the anatomical location of the tumor and estimate the distance from the upper edge of the tumor to the Esophagogastric line. The ultrasonic scalpel was then used to separate the gastrocolic and gastrosplenic ligaments, and the short gastric vessels were divided as needed. After mobilization, if the tumor had not invaded the Esophagogastric line, laparoscopic wedge resection or partial gastrectomy was performed. Once the tumor was fully exposed, a linear stapler was introduced through the 12 mm trocar to excise the lesion. Intraluminal inspection using fiberoptic gastroscopy confirmed the adequacy of the margins. When the tumor was located on the posterior wall, the stomach was rotated to achieve complete visualization, making tumor resection easier. The resected specimen was placed in a plastic bag and removed from the abdomen. Finally, the stapling line was examined using both laparoscopic and endoscopic techniques. If the tumor invaded the EGJ or if the resection techniques mentioned above could not preserve the integrity of the cardia, laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy was performed.

The gastric remnant was anastomosed to the esophagus using a laparoscopic stapler or suturing device to ensure the patency of the anastomosis. Laparoscopic pyloroplasty and gastric plication were also performed. After surgery, patients were closely monitored and underwent postoperative management and follow-up as needed14.

Diagnostic standards

Postoperative specimens were subjected to pathological and immunohistochemical examinations, including the detection of antibodies such as CD117 (c-kit), CD34, SMA, Ki−67%, Desmin, and S−100. Additional molecular tests were performed if necessary. The specimens were then graded for malignant potential20. Each specimen was confirmed by two specialized gastrointestinal pathologists to ensure accurate diagnosis.

Postoperative management and follow-up

Monitor patients’ postoperative symptoms such as fever, chest pain, dyspnea, hematemesis, pleural effusion, and pneumothorax, and promptly manage any discomfort. Adjust the duration of fasting according to the patient’s condition. Perform chest CT if there are suspicions of leakage, infection, or bleeding. Discharge criteria include successful dietary improvement and stable clinical status. Postoperative adverse events are categorized according to the modified Clavian-Dindo classification. Postoperative pathology and genetic testing guide the administration of adjuvant therapy and/or regular follow-up21,22,23,24. For all patients with a potential risk of recurrence, specifically those classified as intermediate or high risk, imatinib is administered as adjuvant therapy to reduce the risk of recurrence. Patients were followed up for long-term outcomes through outpatient or telephone25. The follow-up plan was developed based on the NCCN guidelines: for patients with completely resected 2–5 cm EGJ-GIST, abdominal CT scans were conducted every 3–6 months for the first 3–5 years, followed by annual scans thereafter. For high-risk patients in whom TKI therapy was discontinued, more frequent imaging surveillance was performed. Clinical data, including oncological outcomes and long-term adverse effects, were collected throughout the follow-up period. Patients who cannot be contacted through any available means and have not undergone imaging evaluations at our institution were classified as lost to follow-up. For these patients, we made every effort to re-establish contact using the provided contact information, reaching out to either the patient or their designated family members. We also obtained imaging records of follow-up evaluations that patients may have undergone at local medical institutions, while strictly adhering to ethical standards and data privacy regulations, striving to enhance the completeness and accuracy of follow-up data.

Statistical analysis

We conducted a statistical analysis using IBM SPSS Statistics 25 and R software v4.1.0. Quantitative data underwent normality testing. Normally distributed variables were presented as mean ± SD and analyzed using Student’s t-test. Non-normally distributed variables were described using median and interquartile ranges (IQRs) and assessed through the Wilcoxon rank sum test. The comparison of qualitative data between groups was conducted using either the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. A significance threshold of p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. To compare the ER and LR groups, we performed a propensity score matching analysis. We included variables that could potentially influence treatment outcomes, such as age, gender, tumor size, mitotic count, and risk classification. Propensity scores were derived through logistic regression modeling, and we used these scores to pair patients from the ER group with those from the LR at a 1:1 ratio. We employed the nearest-neighbor approach for propensity score matching, setting the caliper width as a linear transformation of 0.1 times the standard deviation of the propensity score (logit transformation). Matched data were assessed based on the sample distribution, with normally distributed variables analyzed using paired t-tests and non-normally distributed variables evaluated using Wilcoxon rank sum tests.

Results

Baseline clinicopathologic characteristics

During the study period, 43 patients who underwent endoscopic resection (ER) for EGJ-GIST and 42 patients who received laparoscopic resection (LR) were evaluated based on inclusion-exclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Table 1 details the baseline characteristics of both groups before propensity score matching. There were no significant differences in gender or age between the groups. However, symptom distribution and mitotic index varied between the ER and LR groups, with the tumor size in the ER group being significantly smaller (P < 0.01). Additionally, the proportion of low-risk cases was significantly higher in the ER group compared to the LR group (76.7% vs. 40.5%, P = 0.001). All 85 patients underwent follow-up in accordance with established clinical guidelines, and no evidence of tumor recurrence was observed during the follow-up period.

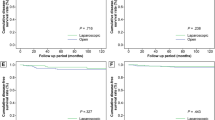

Propensity score matching

After propensity score matching, 20 patients in each treatment group were analyzed. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of demographic and baseline characteristics and operative time, en bloc resection rate, postoperative adverse event rate, and follow-up time (Table 1). Table 2 presents the treatment outcomes of the patients. The postoperative nil per os (NPO) time was 5.5 days (IQRs, 4.3–7.8) in the LR group, significantly longer than in the ER group (4.0 days (IQRs, 3.0–5.0)) (p = 0.005). Median hospital length of stay was significantly lower in the ER group (6.0 days (IQRs, 5.0−6.8)) than LR group (8.5 days (IQRs, 6.0−11.8)) (p = 0.002). The overall long-term adverse event rate was significantly higher in the LR group (55%) than in the ER group (15%) (Fig. 3, p = 0.005). Long-term adverse events include gastroesophageal reflux, heartburn, and anastomotic inflammation, which are unfavorable symptoms that may persist and negatively impact patients’ quality of life. Table 3 shows the clinical features and outcomes of patients with postoperative adverse events. After PSM, the mean follow-up time was 42.3 ± 20.5 months.

Follow-up strategies and outcomes for high-risk EGJ-GIST

In our study, both the ER and LR groups included patients with high-risk GISTs (Table 1). Regardless of whether they were included in the post-PSM analysis, all high-risk patients received postoperative adjuvant imatinib therapy, with no differences in usage between the groups. Additionally, high-risk patients followed the same guideline-based follow-up strategy, which included intensive imaging surveillance (abdominal CT scans every 3–6 months for 3–5 years, followed by annual scans). After these high-risk patients discontinued imatinib under the guidance of their physicians, the frequency of imaging surveillance was increased. All high-risk patients completed the full follow-up, and no recurrences or deaths were observed during the follow-up period.

Discussion

With advancements in technology, laparoscopic and endoscopic surgeries have become preferred choices for minimally invasive procedures. Studies have shown that laparoscopic resection is a safe method for GISTs measuring 2 to 5 cm, and yields favorable oncological outcomes24,26,27,28. However, recent advancements in endoscopic surgical techniques have opened up possibilities for minimally invasive treatment of gastric GISTs. Numerous studies have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of endoscopic surgery for GISTs at common locations, including the stomach2,6,29,30,31,32.

The esophagogastric junction (EGJ) is an important structure with complex anatomical and physiological characteristics. The lower esophageal sphincter (LES) plays a crucial role in maintaining the integrity of the esophagogastric junction and preventing gastric reflux. Relaxation or damage to the LES is a significant factor contributing to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Long-term GERD can lead to esophagitis, ulcers, and strictures, and may even increase the risk of esophageal cancer. Therefore, during the surgical resection of EGJ-GISTs, apart from ensuring complete tumor excision, special attention needs to be given to minimizing damage to the EGJ and its adjacent structures. Avoiding injury to the EGJ and its surrounding nerves and vessels can reduce the risk of postoperative GERD or other gastrointestinal complications, thereby enhancing the safety and success of surgery.

A study comparing the efficacy and prognosis of laparoscopic versus open surgical resection for EGJ-GISTs highlighted that compared to open surgery, laparoscopic surgery causes less trauma and promotes faster recovery, thereby improving short-term outcomes13. However, despite advancements in laparoscopic techniques and minimally invasive surgical instruments, exposing the EGJ field remains challenging, particularly in cases involving gastrointestinal reconstruction13,14. The combination of endoscopy and laparoscopy is a safe and reliable surgical approach4, assisting surgeons in accurately identifying EGJ-GISTs during laparoscopic resection while minimizing damage to the EGJ25,33.

Nevertheless, research on endoscopic treatment for EGJ-GISTs is limited. Therefore, we conducted a retrospective clinical study comparing the efficacy of endoscopic and laparoscopic treatments for EGJ-GISTs. In this study, we compared the safety and efficacy of endoscopic resection (ER) and laparoscopic resection (LR) for EGJ-GISTs measuring 2–5 cm. The results showed several advantages of ER over LR (Table 2; Fig. 3). Firstly, ER patients had significantly shorter postoperative NPO time and postoperative hospitalization time compared to LR patients. Secondly, although there was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of postoperative adverse events between the two groups, all Grade IV postoperative adverse events occurred in the LR group. ER surgery tended to have fewer and milder postoperative adverse events. Lastly, we conducted a detailed evaluation of patients’ long-term outcomes. Symptoms such as acid reflux, heartburn, and anastomotic inflammation are long-term adverse events that affect quality of life. The incidence of long-term adverse events was significantly lower in the ER group compared to the LR group (15% vs. 55%, P = 0.005). Therefore, we believe that compared to LR, ER may be a safer surgical approach for treating EGJ-GISTs measuring 2–5 cm. ER is more likely to preserve the function of the esophagogastric junction, thereby avoiding complications such as esophageal stricture and reflux, and improving patients’ long-term quality of life.

Personalized treatment for GIST patients with different clinical characteristics has been a key focus of research. Previous studies have comprehensively analyzed duodenal GISTs, a rare and anatomically complex form of stromal tumor. The results indicated that limited resection procedures, such as segmental duodenal resection, can effectively treat tumors in specific locations while preserving duodenal function, resulting in favorable oncological outcomes34. Another study on elderly patients presenting gastric GISTs emphasized that, although open surgery remains the traditional approach, minimally invasive techniques such as laparoscopic and endoscopic surgery significantly reduce complications and promote postoperative recovery35. With advancements in minimally invasive techniques, recent discussions regarding esophageal GIST treatment strategies have further clarified management approaches for esophageal GISTs of different sizes and locations, affirming the efficacy of minimally invasive treatment. In particular, for smaller esophageal GISTs, endoscopic treatment is considered the preferred approach due to its safety and minimally invasive nature36.

Our results further highlight that for 2–5 cm EGJ-GISTs, ER offers a better postoperative quality of life, suggesting that ER has advantages in preserving the anatomy and function of the EGJ. ER has clear advantages for smaller tumors confined to the submucosa. However, for larger GISTs that extend beyond the muscularis propria or invade the gastric wall, ER becomes less feasible, and surgical resection remains necessary. Although some studies have indicated that for large gastric GISTs (> 5 cm), ER can achieve comparable outcomes to LR under certain conditions, the feasibility of ER for large, or wall-invading GISTs remains limited8. New endoscopic techniques, such as endoscopic snare traction, may offer additional treatment options for such tumors, but most endoscopists still face technical challenges in real-world practice37.

Although ER offers clear advantages regarding minimal invasiveness, it does not mean that ER can fully replace laparoscopic or robotic surgery. Recent advances in laparoscopic and robotic techniques have enabled surgeons to perform more precise, minimally invasive procedures, even for tumors greater than 5 cm in size or located in anatomically challenging areas, such as the esophagogastric junction, duodenum, posterior gastric wall, and lesser curvature38,39,40. Compared to traditional open surgery, laparoscopic and robotic approaches offer superior visualization and greater operational flexibility, allowing surgeons to more clearly identify the tumor and its surrounding anatomical structures. This not only reduces unnecessary damage to tissue or blood vessels but also shortens surgery time, decreases the incidence of postoperative complications, and preserves the benefits of minimally invasive surgery40. For patients with larger or anatomically challenging tumors, laparoscopic or robotic surgery should be considered an essential treatment option for achieving safer and more effective tumor resection.

A study summarizing the experience of emergency surgery suggests that the treatment approach for GISTs in emergencies requires careful consideration. Although acute GIST presentations are rare in the elderly population, when they do occur, they often manifest as life-threatening complications such as proximal obstruction, acute gastrointestinal bleeding, and perforation35. In these emergencies, prompt and effective intervention is critical. However, because acute GISTs are often associated with fragile tissue, increased bleeding risk, and anatomical disruption, ER may be challenging for complete removal and may further increase the risk of perforation or massive bleeding. Therefore, laparoscopic surgery or open surgery typically becomes a more feasible treatment option. Laparoscopic surgery, while ensuring both safety and feasibility, offers a more minimally invasive approach.

Risk stratification is an essential factor to consider when developing treatment plans. According to Joensuu’s modified NIH classification system, GIST risk stratification primarily relies on tumor size, mitotic index, and the tumor’s primary location41. Currently, some Chinese guidelines suggest that for suspected low-risk GISTs with a tumor diameter greater than 2 cm, preoperative assessment should exclude lymph node or distant metastasis. If the tumor can be completely resected, endoscopic resection may be considered at a facility with advanced endoscopic techniques, performed by an experienced endoscopist. Additionally, some Chinese guidelines recommend that patients for whom surgery can achieve complete tumor resection may proceed directly to resection without the need for routine preoperative biopsy. Both international and Chinese guidelines do not recommend endoscopic resection for GISTs with high-risk features. In our study, the cases included were 2–5 cm EGJ-GISTs, and preoperative evaluation by EUS, CT, and other assessments indicated the absence of high-risk features. Three patients were found to have high-risk features after endoscopic resection, and we followed the guidelines to provide adjuvant therapy and complete follow-up, with no recurrence or mortality observed.

In conclusion, when patients exhibit significant high-risk features, such as tumors > 5 cm or those located in anatomically challenging positions, or emergencies such as severe bleeding or perforation, laparoscopic or robotic surgery should be considered the safer and more reliable options38,40. For patients with smaller tumors (≤ 5 cm) and no high-risk histological features such as tumor rupture, ER offers a minimally invasive, safe, and faster recovery option, particularly for those who cannot tolerate open surgery or wish to preserve EGJ function as much as possible. Therefore, treatment decisions for EGJ-GIST should consider tumor size, location, histological characteristics, clinical presentation (e.g., acute bleeding, perforation, or obstruction), and potential postoperative complications. A rational approach to surgical choice should be made to optimize individualized treatment strategies and achieve the best therapeutic outcomes.

The risk of recurrence in GIST is closely associated with risk stratification factors, including mitotic index and mutation status. According to clinical guidelines, both groups received the same follow-up strategy, including adjuvant therapy and/or regular surveillance based on postoperative pathology and genetic testing results. For patients with intermediate or high recurrence risk who harbor mutations sensitive to imatinib, adjuvant imatinib therapy is recommended to effectively reduce the risk of recurrence. Additionally, for all patients with completely resected 2–5 cm EGJ-GIST, we recommend abdominal CT scans every 3–6 months for 3–5 years, followed by annual surveillance thereafter. After 5 years of follow-up, imaging was done annually. In our study, both the ER and LR groups included patients with high-risk GISTs. High-risk patients in both groups received postoperative adjuvant imatinib therapy, with no differences in usage between the groups. Additionally, high-risk patients followed the same guideline-based follow-up strategy, which included intensive imaging surveillance (abdominal CT scans every 3–6 months). When these high-risk patients discontinued imatinib under the guidance of their physicians, imaging surveillance was intensified. It is noteworthy that, before PSM, the proportion of high-risk GIST cases was higher in the LR group. To mitigate the impact of this factor on comparative outcomes, we incorporated multiple variables that could influence treatment results during the matching process, including tumor size, mitotic index, and risk classification.

In this study, the mean follow-up duration was 42.3 ± 20.5 months, with a maximum follow-up of 100 months. Our preliminary findings suggest that ER can achieve oncological outcomes comparable to those of LR in patients with EGJ-GIST, while potentially offering better quality of life. In addition, based on the inclusion criteria, three patients who were lost to follow-up were excluded in the early stages of the study (Fig. 1). We made every effort to contact the patients or their designated family members and, by ethical and privacy protection principles, attempted to obtain imaging records from local healthcare facilities where the patients may have sought care, striving to optimize tumor management and complete the clinical data. Since these three patients were from the low-risk group and were excluded early in the study based on the inclusion criteria, their proportion is small (a total of 85 patients included before PSM), and therefore their impact on the conclusions of this study is limited.

Due to the potential risk of recurrence of GISTs exceeding five years, the average follow-up period of 42.3 months in this study is relatively short for assessing long-term tumor outcomes. Previous studies indicate that GISTs may still recur after more than 10 years of follow-up42. The EGJ-GISTs we focused on are located in a unique anatomical position, which may confer distinct biological characteristics. Compared to gastric GISTs, tumors located at the GEJ have a shorter overall survival (OS) and a higher rate of distant metastasis43. Furthermore, following PSM, each group in our study had only 20 patients, which limits the statistical power and generalizability of the results. Therefore, extending the follow-up period to 5–10 years and increasing the sample size is necessary. Although this study demonstrated a significantly lower incidence of long-term adverse events, such as GERD and anastomotic inflammation, in the ER group, there was a lack of structured patient-reported outcomes to comprehensively assess quality of life (QoL). Future studies should incorporate validated QoL tools, such as GERD-HRQL (Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease-Health Related Quality of Life) and EORTC QLQ-STO22 (European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Stomach 22), to more objectively evaluate functional outcomes. During follow-up, some patients underwent endoscopic evaluations, confirming the preservation of EGJ integrity in ER patients. However, because endoscopic assessments were not routinely performed, the anatomical integrity of the EGJ could not be directly verified in some cases. Therefore, the conclusion that ER better preserves EGJ integrity compared to LR is mainly based on the incidence of long-term adverse events such as GERD and whether the cardia was resected during laparoscopic surgery, rather than direct physiological assessments.

To address the limitations of this preliminary study, we plan to conduct a large-sample, multicenter prospective study to validate whether endoscopic resection improves postoperative recovery and reduces complications. The study will integrate artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted imaging and biomarker testing to enhance preoperative assessment and guide personalized treatment strategies based on tumor characteristics, clinical presentation, and risk of complications. Follow-up will be extended to at least 5–10 years to capture late recurrence. The study will implement risk-based follow-up protocols, with more attention given to high-risk patients, and will adopt stricter follow-up management to minimize loss to follow-up. Additional assessments, including esophageal manometry and endoscopic reevaluation, will be used to evaluate EGJ integrity. Validated quality of life tools, such as GERD-HRQL and EORTC QLQ-STO22, will assess functional outcomes.

This comprehensive approach will support a detailed comparison of ER versus LR in EGJ-GIST patients, aiming to optimize treatment and improve long-term outcomes.

Conclusion

Endoscopic resection is a promising alternative therapeutic modality for EGJ-GISTs measuring 2 to 5 cm. Its advantages include reduced trauma, potential preservation of the anatomical integrity of the EGJ, shorter hospital stay, fewer adverse events, and notable enhanced long-term quality of life. In the future, we aim to conduct large-scale, multicenter prospective studies to further explore the evolving landscape of treatment strategies for EGJ-GIST, with the ultimate goal of achieving personalized precision treatment for patients.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Joensuu, H., Hohenberger, P. & Corless, C. L. Gastrointestinal stromal tumour. Lancet (London England). 382, 973–983 (2013).

Casali, P. G. et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO-EURACAN-GENTURIS clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals Oncology: Official J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 33, 20–33 (2022).

Piessen, G. et al. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for gastric Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: what is the impact on postoperative outcome and oncologic results?? Ann. Surg. 262, 831–839 (2015). discussion 829–840.

Matsuda, T. et al. Laparoscopic and luminal endoscopic cooperative surgery can be a standard treatment for submucosal tumors of the stomach: a retrospective multicenter study. Endoscopy 49, 476–483 (2017).

Goh, B. K. et al. Outcome after laparoscopic versus open wedge resection for suspected gastric Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A matched-pair case-control study. Eur. J. Surg. Oncology: J. Eur. Soc. Surg. Oncol. Br. Association Surg. Oncol. 41, 905–910 (2015).

Kim, G. H. et al. Comparison of the treatment outcomes of endoscopic and surgical resection of GI stromal tumors in the stomach: a propensity score-matched case-control study. Gastrointest. Endosc. 91, 527–536 (2020).

Chen, T. et al. No-touch endoscopic full-thickness resection technique for gastric Gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Endoscopy 55, 557–562 (2023).

Zhang, J., Cao, X., Dai, N., Zhu, S. & Guo, C. Efficacy analysis of endoscopic treatment of giant gastric Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (≥ 5 cm). Eur. J. Surg. Oncology: J. Eur. Soc. Surg. Oncol. Br. Association Surg. Oncol. 49, 106955 (2023).

Mittal, R. K. & Balaban, D. H. The esophagogastric junction. N. Engl. J. Med. 336, 924–932 (1997).

Odze, R. D. Unraveling the mystery of the gastroesophageal junction: a pathologist’s perspective. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 100, 1853–1867 (2005).

Sakamoto, Y. et al. Safe laparoscopic resection of a gastric Gastrointestinal stromal tumor close to the esophagogastric junction. Surg. Today. 42, 708–711 (2012).

Privette, A., McCahill, L., Borrazzo, E., Single, R. M. & Zubarik, R. Laparoscopic approaches to resection of suspected gastric Gastrointestinal stromal tumors based on tumor location. Surg. Endosc. 22, 487–494 (2008).

Xiong, W. et al. Laparoscopic vs. open surgery for Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of esophagogastric junction: A multicenter, retrospective cohort analysis with propensity score weighting. Chin. J. cancer Res. = Chung-kuo Yen Cheng Yen Chiu. 33, 42–52 (2021).

Xiong, W. et al. Laparoscopic resection for Gastrointestinal stromal tumors in esophagogastric junction (EGJ): how to protect the EGJ. Surg. Endosc. 32, 983–989 (2018).

Tanigawa, K. et al. Safety of laparoscopic local resection for Gastrointestinal stromal tumors near the esophagogastric junction. Surg. Today. 52, 395–400 (2022).

Siewert, J. R., Hölscher, A. H., Becker, K. & Gössner, W. [Cardia cancer: attempt at a therapeutically relevant classification]. Der Chirurg; Z. fur Alle Gebiete Der Operativen Medizen. 58, 25–32 (1987).

Shi, Q. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for treatment of esophageal submucosal tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer. Gastrointest. Endosc. 74, 1194–1200 (2011).

Zhou, J., Zhang, J. & Zhang, X. Pursestring encirclement before endoscopic submucosal excavation of a cecal submucosal tumor. Endoscopy 55, E1160–e1161 (2023).

Rajan, E. & Wong Kee Song, L. M. Endoscopic full thickness resection. Gastroenterology 154, 1925–1937e1922 (2018).

Koo, D. H. et al. Asian consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Cancer Res. Treat. 48, 1155–1166 (2016).

Kumta, N. A., Saumoy, M., Tyberg, A. & Kahaleh, M. Submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection for En bloc removal of large esophageal Gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Gastroenterology 152, 482–483 (2017).

Xu, J. X. et al. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic resection for the treatment of esophageal Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a ten-year experience from a large tertiary center in China. Surg. Endosc. 37, 5883–5893 (2023).

Shinagare, A. B. et al. Esophageal Gastrointestinal stromal tumor: report of 7 patients. Cancer Imaging: Official Publication Int. Cancer Imaging Soc. 12, 100–108 (2012).

Mohammadi, M. et al. Clinicopathological features and treatment outcome of oesophageal Gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST): A large, retrospective multicenter European study. Eur. J. Surg. Oncology: J. Eur. Soc. Surg. Oncol. Br. Association Surg. Oncol. 47, 2173–2181 (2021).

Ye, X., Yu, J., Kang, W., Ma, Z. & Xue, Z. Short- and Long-Term outcomes of Endoscope-Assisted laparoscopic wedge resection for gastric submucosal tumors adjacent to esophagogastric junction. J. Gastrointest. Surgery: Official J. Soc. Surg. Aliment. Tract. 22, 402–413 (2018).

Blum, M. G. et al. Surgical considerations for the management and resection of esophageal Gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 84, 1717–1723 (2007).

Lee, H. J., Park, S. I., Kim, D. K. & Kim, Y. H. Surgical resection of esophageal Gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 87, 1569–1571 (2009).

Jiang, P. et al. Clinical characteristics and surgical treatment of oesophageal Gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Eur. J. cardio-thoracic Surgery: Official J. Eur. Association Cardio-thoracic Surg. 38, 223–227 (2010).

Miettinen, M. & Lasota, J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors–definition, clinical, histological, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic features and differential diagnosis. Virchows Archiv: Int. J. Pathol. 438, 1–12 (2001).

Zhang, Y., Ye, L. P. & Mao, X. L. Endoscopic treatments for small gastric subepithelial tumors originating from muscularis propria layer. World J. Gastroenterol. 21, 9503–9511 (2015).

Joo, M. K. et al. Endoscopic versus surgical resection of GI stromal tumors in the upper GI tract. Gastrointest. Endosc. 83, 318–326 (2016).

Feng, F. et al. Comparison of endoscopic and open resection for small gastric Gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Translational Oncol. 8, 504–508 (2015).

Xiao, G., Liu, Y. & Yu, H. Laparoscopic transgastric resection for intraluminal gastric Gastrointestinal stromal tumors located at the posterior wall and near the gastroesophageal junction. Asian J. Surg. 42, 653–655 (2019).

Marano, L., Boccardi, V., Marrelli, D. & Roviello, F. Duodenal Gastrointestinal stromal tumor: from clinicopathological features to surgical outcomes. Eur. J. Surg. Oncology: J. Eur. Soc. Surg. Oncol. Br. Association Surg. Oncol. 41, 814–822 (2015).

Marano, L., Arru, G. M., Piras, M., Fiume, S. & Gemini, S. Surgical management of acutely presenting Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach among elderly: experience of an emergency surgery department. Int. J. Surg. (London England). 12 (Suppl 1), 145–147 (2014).

Zhu, S. et al. Optimal management options for esophageal Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (E-GIST). Eur. J. Surg. Oncology: J. Eur. Soc. Surg. Oncol. Br. Association Surg. Oncol. 50, 108527 (2024).

Zhang, J. W. et al. Endoscopic resection of extra-luminal gastric Gastrointestinal stromal tumors using a snare assisted external traction technique (with video). Dig. Liver Disease: Official J. Italian Soc. Gastroenterol. Italian Association Study Liver (2024).

Huang, C. M. et al. Can laparoscopic surgery be applied in gastric Gastrointestinal stromal tumors located in unfavorable sites? A study based on the NCCN guidelines. Medicine 96, e6535 (2017).

Lin, S. C., Yen, H. H., Lee, P. C. & Lai, I. R. Oncological outcomes of large Gastrointestinal stromal tumors treated by laparoscopic resection. Surg. Endosc. 37, 2021–2028 (2023).

Park, S. H. et al. Early experience of laparoscopic resection and comparison with open surgery for gastric Gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a multicenter retrospective study. Sci. Rep. 12, 2290 (2022).

Joensuu, H. Risk stratification of patients diagnosed with Gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Hum. Pathol. 39, 1411–1419 (2008).

Joensuu, H. et al. Risk of recurrence of Gastrointestinal stromal tumour after surgery: an analysis of pooled population-based cohorts. Lancet Oncol. 13, 265–274 (2012).

Abdalla, T. S. A. et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the upper GI tract: population-based analysis of epidemiology, treatment and outcome based on data from the German clinical Cancer registry group. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 149, 7461–7469 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Z. collected study materials and article data, performed data curation, visualized results, and wrote the original draft. Z.L., J.Z., and N.D. collected study materials and article data. S.U., G.Z., and Z.Z. constructed the article structure framework. S.Z., Y.X., L.C., and S.Z. collected article data and visualized results. P.L. and Y.F. collected data and revised the article. C.G. and X.C. revised the article and supervised the project. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Scientific Research and Clinical Trials of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (Approval No. 2022-KY-1236-001), and was conducted by the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The data were anonymized and the study was retrospective, and the Scientific Research and Clinical Trial Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University waived the requirement of informed consent for the study subjects. All the authors have followed the applicable ethical standards to maintain the research integrity without any duplication, fraud, or plagiarism issues.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, S., Liu, Z., Zhang, J. et al. Endoscopic versus laparoscopic resection of gastrointestinal stromal tumors at the esophagogastric junction using propensity score matching analysis. Sci Rep 15, 15916 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98859-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98859-3