Abstract

This study examined whether childhood sports club experiences mitigate the association between childhood socioeconomic disadvantage and later life functional disability among older adults using a population-based study in Japan in a moderation analysis (n = 16,095, average age = 73 years). Functional disability was assessed using a 13-item measure of higher-level functional ability; scores below the 10th percentile indicated functional disability. Childhood socioeconomic status (SES) at age 15 years was assessed according to time-appropriate standards. Childhood sports club experiences were assessed according to the extent of club/group sports experience during different age periods. For both sexes, lower childhood SES was associated with higher functional disability risk, and longer cumulative childhood sports club experience was associated with lower risk. Childhood sports club experiences modified the association between childhood SES and functional disability in men. Among men with low childhood SES, those with two or more periods of childhood sports club experience had substantially lower functional disability risk than those with no experience (adjusted odds ratio = 0.32, 95% confidence interval: 0.21–0.50). In women, childhood sports club experience did not modify the association with functional disability, but it modified the association with impaired intellectual activity, a subscale of higher-level functional ability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Functional disability is a frequent consequence of aging and is associated with several adverse outcomes, such as institutionalization1, poor mental health,2 and mortality3 Functional disability is assessed in terms of difficulties performing activities of daily living (ADLs) and is evaluated from two perspectives: basic ADLs and instrumental ADLs (IADLs)4 Basic ADLs are activities necessary for independent living, such as dressing, walking, and bathing; IADLs are higher level activities than ADLs that are more complex and require a greater level of personal autonomy, such as preparing meals, grocery shopping, and taking medications5 In this paper, “functional disability” is defined and used as having difficulties with higher level functional activities, i.e., IADLs. Functional disability not only decreases quality of life and increases health risks, but also increases caregiver burden6,7,8,9 Therefore, it is important to understand the determinants of functional disability.

Recent studies in life-course epidemiology suggest that childhood socioeconomic status (SES) is an important determinant of functional disability in later life10,11,12,13,14,15 Lower childhood SES, as assessed by parental education, father’s occupation, and subjective social status, is associated with increased risk of later functional disability10,11,12,13,14,15 However, factors that mitigate the risk of functional disability owing to low SES in childhood are unknown.

Participation in sports groups in old age has been reported to potentially benefit functional disability16,17 A study conducted among Japanese older adults showed that exercise at least once a month was associated with a lower risk of functional disability defined by certification of long-term care. Furthermore, exercisers participating in a sports group had a lower risk than exercisers not participating in a sports group16 In the study, the difference in risk with or without sports group participation was partially explained by social ties17 Sports groups participation provides not only opportunities of exercise but also fostering social relationships16,17.

Childhood experiences participating in sports club mitigate the risk of functional disability owing to low SES in childhood. Japanese schools have a unique system of extracurricular sports activities. After World War II, Japanese educational policy encouraged sports club activities, as schools should recognize the value that sportsmanship and a spirit of cooperation possessed18 Physical Education guidelines emphasized voluntary activities by students, not forced by teachers, so school sports club were recommended as extracurricular activities18 Extracurricular school clubs are usually held on school ground, and more than half of the school teacher is involved in running the clubs, including providing guidance and advice18 In 1955, about half of junior high school students and one-third of high school students participated in extracurricular sports club, spending an average of three to five days a week18 Sports clubs include diverse sports, such as baseball, basketball, soccer, field track, judo, and swimming, with an average of 10 clubs per school in junior high schools and 14 clubs per school in high schools in Japan, according to the 2017 National Survey19.

A review of studies on the influence of school sports club activities in Japan showed that sports clubs contribute to children’s exercise, psychosocial development, school life enrichment, and building of social relationships20 Therefore, we hypothesized that childhood sports experiences are associated with later life functional ability through subsequent sports club participation, increased exercise, and fostering social relationships. Those with low childhood SES are less likely to participate in sports groups and are less physically active21,22 Low childhood SES was also associated with lower social relationships later in life23 Therefore, childhood sports club experiences may be effective in preventing functional disability in later life, especially in disadvantaged groups.

The prevalence of sports club activity differs between boys and girls18 There are also sex differences in the association between childhood SES and the health of older adults in Japan24 Lower childhood SES was associated with lower mortality in men, but not in women24 Therefore, the study aim was to examine whether childhood sports club experience moderates the association between childhood SES and functional disability in older age, separately for men and women, using a population-based study of Japanese adults.

Methods

Study design and participants

Data from the 2016 survey of the Japan Aging and Gerontological Evaluation Study (JAGES), a nationwide research project on aging25 The survey was conducted in 39 municipalities across Japan and included older adults aged ≥ 65 years who were not certified as eligible for long-term care services under the public long-term care insurance system26 The survey was conducted in 22 large municipalities using random sampling, and all eligible residents in 17 small municipalities were invited to participate. Self-report questionnaires were mailed to 279,661 older adults between October 2016 and January 2017; 196,438 returned the questionnaires (response rate 70.2%). In some municipalities, recipients of public long-term care insurance were also included in the survey at the request of the local government; the number of eligible residents excluding such recipients was 180,021. One-eighth of the sample (N = 22,263) was randomly selected to receive a survey module on childhood sports club experiences. Participants were excluded if they had missing data on childhood SES, on childhood sports club experience, on functional disability items, or on sex. Therefore, data were analyzed for 16,095 participants (7,834 men and 8,261 women). A flow chart of the participants is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Functional disability

Functional disability was assessed using the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology Index of Competence (TMIG-IC); this scale assesses IADLs and its validity and reliability have been demonstrated27 The TMIG-IC has three subscales: instrumental self-maintenance (five items: ability to use public transport, shop for daily necessities, prepare meals, pay bills, and handle a bank account), intellectual activities (four items: ability to fill out forms, read newspapers, read books/magazines, and interest in television programs/news articles on health), and social roles (four items: ability to visit friends’ homes, give advice to relatives and friends, visit someone in hospital, and initiate conversation with younger people)28 Response options for the instrumental self-maintenance items were (1) Yes, I can and do; (2) Yes, but I don’t; (3) No. The first two responses were scored as 1. Response options for the intellectual activities and social roles items were yes/no; a response of yes was scored as 1. The total score was calculated (possible range: 0–13 points). Higher scores indicated higher levels of IADLs. A participant was defined as having a functional disability if the score of the ≤ 10th percentile (corresponds to a score of ≤ 9), which is associated with subsequent IADL decline and a higher risk of stroke or death6,7,8 For the three TMIG-IC subscales, instrumental self-maintenance was considered impaired on a subscale if it scored 4 or less out of 5, and intellectual activities and social roles scored 3 or less out of 4, following previous studies8,29.

Childhood SES

Childhood SES was assessed with the following question: “How would you rate your standard of living at the age of 15 years according to standards at that time?”24 For example, a respondent aged 75 years in 2016 would recall their situation in 1956 when they were 15 years old. Participants responded on a 5-point Likert scale: “high,” “middle-high,” “middle,” “middle-low,” and “low.” In accordance with previous studies,21,24,30 responses were collapsed into three categories: “high” (including “high” and “middle-high”), “middle,” and “low,” (including “middle-low” and “low”). The low childhood SES using this assessment was associated with a higher risk of depression, lower social relationships, and less frequent consumption of fruits and vegetables; thus, it has predictive validity23,30,31.

Childhood sports club experiences

Childhood sports club experiences were assessed with the following question: “In the past, did you regularly exercise or play sports as a member of an extracurricular sports club, company sports club, or any other type of sports group (Do NOT count physical education classes in school)?” Here, “regularly” referred to exercising or playing sports for at least 20 min each time, not less than once a week, and for at least 6 continuous months. This definition was based on the maintenance stage questions of the transtheoretical model, which has been validated for Japanese adults32 Participants were asked to select all applicable age periods (i.e., 6 to 12). Because this study focused on childhood experiences, the responses for the three age periods 6–12, 13–15, and 16–18 were used to determine childhood sports club experiences, and the cumulative duration of the experiences (0, 1, ≥ 2 periods) was calculated. These three periods were defined according to the Japanese educational system (i.e., elementary school 6–12 years, junior high school 13–15 years, and high school 16–18 years).

Covariates

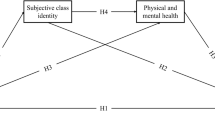

Covariates were assessed by self-report questionnaire. Potential confounders of the association between childhood SES and functional disability included age and educational attainment (≤ 9, 10–12, or ≥ 13 years) (Supplementary Fig. 2 (a)) Potential mediators of the association between childhood sports club experience and functional disability comprised adult SES, adult sports experience/physical activity, adult social relationships, and adult body mass index (BMI) (Supplementary Fig. 2 (b)). Adult SES comprised of longest-held occupation (non-manual (professional, technical, or managerial workers), manual (clerical, sales/service, skilled/labor, or agricultural/forestry/fishery workers, or other), or no occupation); current annual household income (< 2.00, 2.00–3.99, or ≥ 4.00 million yen); and home ownership (own home or renting). Adult sports experience/physical activity comprised of adult (ages 19–59) or older adults (age 60 and older) sports group experience (yes or no); exercise (no exercise, some exercise, or regular exercise); moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (0, < 1, or ≥ 1 h/day), and walking time (< 30, 30–59, 60–89, or ≥ 90 min/day)24. Adults (ages 19–59) or older adults (ages 60 and older) sports group experience were assessed using the same questions as for their childhood sports club experience. Current exercise was assessed by asking whether the person exercises at least once a week for at least 20 min per session. Current moderate-to-vigorous physical activity was assessed by asking how many hours are they spending performing physical work or intense sports during an average day, including while you’re working33 Adult social relationships comprised of marital status (married, widowed, divorced, or unmarried/other); number of meeting friends (0, 1–5, or ≥ 6 times/month); frequency of meeting friends (0, < 1, ≥1/week), social participation in the following groups or activities, volunteer groups, hobby activity groups, study or cultural group, or skills teaching; emotional social support from friends (absent or present), and neighborhood ties (high, middle, or low)34,35,36 Cognitive function was assessed using three items from the Kihon Checklist–Cognitive Function scale, which has been confirmed predictive validity for the dementia incidence37.

Statistical analysis

First, we examined whether childhood sports club experiences mitigate the association between childhood socioeconomic disadvantage and later life functional disability in a moderation analysis. To examine the interaction effect of childhood SES and cumulative childhood sports club experience on functional disability, logistic regression analysis yielded odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for functional disability. In this analysis, only age was added to the model as a possible confounding factor (Supplementary Fig. 2 (a)). Cognitive function was added as a covariate to account for recall bias of childhood SES. Furthermore, to determine which types of functional ability were associated with childhood sports club experience, logistic regression analysis was used to examine the association with each subscale of the functional ability (TMIG-IC). Second, differences in characteristics by cumulative childhood sports club experience were tested using the chi-square test. Third, the data were analyzed using stratification by childhood SES level if the interaction term was significant. The following models were selected for the analysis of the association between childhood sports club experience and functional disability (Supplementary Fig. 2 (b)): Model 1 adjusted for age and educational attainment as potential confounders; Model 2 additionally adjusted for adult SES (longest occupation and normalized current household income) as potential mediators; Model 3 further adjusted for adult sports experience/physical activity as potential mediators; Model 4 further adjusted for adult social relationships as potential mediators; Model 5 further adjusted for adult BMI as potential mediators. Fourth, we conducted a mediation analysis to determine the proportion of the association between childhood sports club experience and functional disability that was mediated by potential mediators (adult SES, adult sports experience/physical activity, and adult social relationships). Using the Paramed package in Stata38, we estimated the indirect effects via mediators after controlling for potential confounders (age and educational attainment). Participants with missing data on the covariates were included in the analysis. All analyses were conducted using Stata statistical software Macro Package version 17 (Stata Corporation, TX, USA).

Results

Approximately 40% of participants were aged > 75 years, and 30% had < 9 years of education (Supplementary Table 1). The timing of childhood club sports experience differed between the sexes. Men were most involved in sports clubs when they were 16–18 years old. Females most participated in sports clubs when they were 13–15 years old. Cumulative childhood sports club experience also differed between the sexes, men were more likely to have participated in sports clubs for longer periods. Table 1 shows the prevalence of sports club experience by childhood SES. For both men and women, lower childhood SES was associated with lower prevalence of sports experience across the respective age periods. However, even with lower childhood SES, 36% of males and 11% of females had at least one period of sports club experience.

For both sexes, both childhood SES and cumulative experience of childhood sports club were independently associated with functional disability in older age (Table 2). For men, the OR for low childhood SES (vs. high SES) was 1.28 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.03–1.60), and the OR for two or more periods of sports club experience (vs. no sports experience) was 0.45 (95% CI: 0.36–0.57). The interaction between childhood SES and cumulative sports club experience was significant (p = 0.001 for interaction). When cognitive function was added as a covariate to account for recall bias of childhood SES, the results did not change (data not shown).

Figure 1 shows the prevalence of functional disability by cumulative childhood sports experience among men according to childhood SES. Of participants with no childhood sports experience, those with low childhood SES showed a higher prevalence of functional disability than those with high childhood SES. However, participants with low childhood SES who had had two periods of childhood sports experience showed a 6.2% functional disability prevalence, lower than that for participants with middle or high childhood SES with two periods of childhood sports experience (9.1% and 12.4%, respectively).

When analyzed on the three subscales of the functional ability (TMIG-IC) in men, the interaction term between childhood SES and cumulative sports club experience was p = 0.047 for impaired instrumental self-maintenance, p = 0.37 for impaired intellectual activity, and p = 0.11 for impaired social roles in men (Supplementary Table 2). This indicates that the association of risk reduction with childhood sports club experience tends to differ by childhood SES in instrumental self-maintenance and social roles.

In women, the OR for low childhood SES (vs. high SES) was 1.89 (95% CI: 1.47–2.43), and the OR for two or more periods of sports club experience (vs. no sports experience) was 0.48 (95% CI: 0.31–0.76) (Table 2). However, the interaction between childhood SES and cumulative sports club experience was non-significant (p > 0.6 for interaction). When analyzed on the three subscales of the functional ability (TMIG-IC), the interaction term between childhood SES and cumulative sports club experience was significant only for impaired intellectual activity (p < 0.001 for interaction) (Supplementary Table 2).

Supplementary Tables 3 and 4 show the characteristics of older Japanese men and women according to cumulative experience of childhood sports club. The longer periods of childhood sports club experience, the more likely they were to have a non-manual job, higher income, more sports experience in adulthood, more current exercise and physical activity, more likely to be married, and rich social relationships with friends, but not home ownership for both men and women.

Table 3 shows the association between cumulative childhood sports club experience and functional disability according to childhood SES in men. Age and education-adjusted results showed that compared with those with no childhood sports club experience, participants with two or more periods of experience had an OR of 0.96 (95% CI: 0.54–1.71) for high, 0.64 (95% CI: 0.45–0.89) for middle, and 0.32 (95% CI: 0.21–0.50) for low childhood SES (Model 1). Additional adjustments for adult SES did not substantially change the association (Model 2). Additional adjustments for adult sports experience/physical activity and social relationships weakened the association (Models 3 and 4), but additional adjustments for adult BMI did not weaken the association (Models 5).

For the subscales of the functional ability, cumulative childhood sports club experience was significantly associated with a lower risk of impaired instrumental self-maintenance or social role when childhood SES was middle or low in men in models adjusted for potential confounders. (Model 1 in Supplementary Table 5). These associations became non-significant when adjusted for adult sports experience/physical activity and social relationships.

In women, the association between childhood sports club experience and functional disability was attenuated when adjusting for adult sports experience/physical activity, and adult social relationships (Models 4 and 5 in Supplementary Table 6), but not when adjusted for BMI (Models 6 in Supplementary Table 6). For the subscales of the functional disability, cumulative childhood sports club experience was associated with a lower risk of impaired intellectual activity when childhood SES was middle or low (Supplementary Table 5). This association became non-significant when adjusted for adult sports experience/physical activity (Model 3 in Supplementary Table 5).

Supplementary Table 7 shows the mediation results for the hypothesized mediators between childhood sports club experience and functional disability among men with low childhood SES. The results showed evidence of mediation in current income, sports group experience in adulthood, current exercise, number and frequency of meeting friends, and social support.

Supplementary Table 8 shows the mediation results for hypothesized mediators between childhood sports club experience and impaired intellectual activity among women with low childhood SES. The results showed evidence of mediation in current exercise, number and frequency of meeting friends.

Discussion

The cumulative experience of childhood sports club was associated with a lower risk of functional disability in older age in both sexes. Longer duration of childhood sports club experience mitigated the association between low childhood SES and functional disability in older men. In older women, childhood sports experience did not modify the association with functional disability, but it modified the association with impaired intellectual activity, a subscale of functional ability.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to show that childhood sports club experiences modify the association between childhood SES and health in older age. This novel finding may reflect the unique system of extracurricular sports activity in Japanese schools, which may explain the relatively high prevalence of sports experience even in the low SES group (Table 1)18.

Previous reports have identified three possible pathways of socioeconomic inequality in children’s sports participation: financial (sports club membership fees), value (parental support), and place of residence (availability of sports facilities)39 The provision of free extracurricular sports club in Japanese schools reduces financial and geographical inequalities. Furthermore, several Japanese cartoons feature sports such as baseball (e.g., Batto kun), which motivate children to join sports clubs, and parents tend to encourage such activities40 We confirmed among those with lower childhood SES, 36% of males and 11% of females had at least one period of sports club experience (Table 1). Therefore, socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals in Japan can experience the benefits of school sports clubs.

For men, the benefits of childhood sports club experience on functional ability were greater when childhood SES was lower on the two subscales of the functional disability. (instrumental self-maintenance and social roles) (Supplementary Table 2). A possible explanation for this moderation effect is as follows. First, men with lower childhood SES may be more sensitive to stimuli such as sports club participation as a potential means to move out of lower social strata. In Japan, male students who excelled in sports had given priority for admission to universities even before the recommendation-based admission system was officially approved in 196741 Thus, cumulative childhood sports experience may have contributed to subsequent higher education and higher financial status in adulthood. We found that only among men with low childhood SES, males with longer childhood sports club experience tended to be employed in non-manual employment and had higher incomes, i.e., higher SES in adulthood. (Supplementary Table 9).

Second, the lower childhood SES, the more likely it is that childhood sports club experiences contributed significantly to later participation in sports groups and physical activity. We confirmed that childhood sports club experience was associated with functional disability in men with low childhood SES, via adulthood sport group experience and older aged exercise (Supplementary Table 7). Third, this may be explained by the fostering of social relationships brought about by the sports clubs42 We confirmed that social relationships in adulthood mediate the association between childhood sports experiences and functional disability in men with low childhood SES (Supplementary Table 7). In our Japanese setting, extracurricular sports club activity may have been the main opportunity for low SES children to make lifelong friends (Supplementary Table 9).

Childhood sports club experience did not modify the association between childhood SES and functional disability but did modify the association with impaired intellectual activity among women. Among women with low childhood SES, the longer period of childhood sports club experience was associated with regular older aged exercise (Supplementary Table 10). Older aged exercise mediated 40% of the association between childhood sports club experience and impaired intellectual activity (Supplementary Table 8). Therefore, for those with low childhood SES, childhood sports club experience is a predictor in engaging in exercise in old age. Another possible explanation is physical activity during sports club changes brain structure and engaging in sports in late childhood positively affects cognitive function43 Childhood socioeconomic disparities are associated with differences in brain structure and cognitive development44,45.

There were several study limitations. First, childhood SES was assessed via subjective recall. However, the reliability of retrospective assessment of childhood SES using sibling recollections has been demonstrated46 Childhood subjective SES also correlated with other objective indicators of poverty, such as SES in adulthood24 Second, the validity and reliability of the ratings of childhood sports club experiences have not been confirmed. However, the presence of sex differences and socioeconomic inequalities in the prevalence of sports experience is consistent with previous research18,39 Third, the location and the type of sports club experience were not assessed. In addition, whether the sports experience was in team or individual sports was not evaluated. Deeper understanding of these issues is needed to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and consider specific interventions. Fourth, women-specific physiological and psychological experiences were not examined in the mediation analysis. Fifth, the association between childhood status and functional disability may have been underestimated because the participants were not certified as long-term care. Finally, as this was a cross-sectional study, it was not possible to determine causal relationships. Future study is needed using longitudinal studies.

There were sex and socioeconomic disparities in the timing and maintenance of childhood sports club experiences among older Japanese adults. In recent years, Japan has been promoting the development of a system that allows local communities to secure opportunities for activities that could replace sports club activities to reduce the burden on school teachers involved in sports club management47 Because of this social disparity in sports club experience, it will be important to create a system where socioeconomically disadvantaged children can enjoy the benefits provided by sports clubs.

A new perspective on the benefits of childhood sports club experiences was added. Cumulative childhood sports club experience was associated with a lower risk of functional disability in older age in both men and women. Childhood sports club experience moderated the association between childhood disadvantage and functional disability in older age in men. In women, childhood sports club experience modified the association with impaired intellectual activity, a subscale of functional ability. Although these findings require replication in other settings, they suggest that a sports environment that is accessible to socioeconomically disadvantaged children may contribute to later functional ability.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from JAGES Agency but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with permission of JAGES Agency (dataadmin.ml@jages.net).

References

Hajek, A. et al. Longitudinal predictors of institutionalization in old age. PLoS One. 10, e0144203. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0144203 (2015).

Maier, A., Riedel-Heller, S. G., Pabst, A. & Luppa, M. Risk factors and protective factors of depression in older people 65+. A systematic review. PLoS One. 16, e0251326. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251326 (2021).

Millán-Calenti, J. C. et al. Prevalence of functional disability in activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) and associated factors, as predictors of morbidity and mortality. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 50, 306–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2009.04.017 (2010).

World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. (2001).

Mlinac, M. E. & Feng, M. C. Assessment of activities of daily living, Self-Care, and independence. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 31, 506–516. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acw049 (2016).

Taniguchi, Y. et al. Association of trajectories of Higher-Level functional capacity with mortality and medical and Long-Term care costs among Community-Dwelling older Japanese. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 74, 211–218. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/gly024 (2019).

Iwasaki, M. & Yoshihara, A. Dentition status and 10-year higher-level functional capacity trajectories in older adults. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 21, 48–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.14099 (2021).

Murakami, K. et al. Impaired Higher-Level functional capacity as a predictor of stroke in Community-Dwelling older adults: the Ohasama study. Stroke 47, 323–328. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.115.011131 (2016).

Riffin, C., Van Ness, P. H., Wolff, J. L. & Fried, T. Multifactorial examination of caregiver burden in a National sample of family and unpaid caregivers. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 67, 277–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15664 (2019).

Freedman, V. A., Martin, L. G., Schoeni, R. F. & Cornman, J. C. Declines in late-life disability: the role of early- and mid-life factors. Soc. Sci. Med. 66, 1588–1602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.037 (2008).

Turrell, G., Lynch, J. W., Leite, C., Raghunathan, T. & Kaplan, G. A. Socioeconomic disadvantage in childhood and across the life course and all-cause mortality and physical function in adulthood: evidence from the Alameda County study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 61, 723–730. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2006.050609 (2007).

Bowen, M. E. & González, H. M. Childhood socioeconomic position and disability in later life: results of the health and retirement study. Am. J. Public. Health. 100 (Suppl 1), 197–203. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2009.160986 (2010).

Fujiwara, T., Kondo, K., Shirai, K., Suzuki, K. & Kawachi, I. Associations of childhood socioeconomic status and adulthood height with functional limitations among Japanese older people: results from the JAGES 2010 project. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 69, 852–859. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glt189 (2014).

Haas, S. Trajectories of functional health: the ‘long arm’ of childhood health and socioeconomic factors. Soc. Sci. Med. 66, 849–861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.004 (2008).

Landös, A. et al. Childhood socioeconomic circumstances and disability trajectories in older men and women: a European cohort study. Eur. J. Public. Health. 29, 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cky166 (2019).

Kanamori, S. et al. Social participation and the prevention of functional disability in older Japanese: the JAGES cohort study. PLoS One. 9, e99638. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0099638 (2014).

Kanamori, S. et al. Participation in sports organizations and the prevention of functional disability in older Japanese: the AGES cohort study. PLoS One. 7, e51061. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0051061 (2012).

Nakazawa, A. A Postwar History of Extracurricular Sport Activities in Japan (1): Focusing on the Transition of the Actual Situation and Policy25–46 (Tokyo, 2011). (in Japanese).

Japan Sports Agency. Survey on Sports Club Activities in School (Tokyo, 2018). (in Japanese).

Imashuku, H., Asakura, M., Sakuno, S. & Shimazaki, M. A review of the studies on the effectiveness of school athletic club activities. Japan J. Phys. Educ. Hlth Sport Sci. 64, 1–20 (2019).

Yamakita, M. et al. Association between childhood socioeconomic position and sports group participation among Japanese older adults: A cross-sectional study from the JAGES 2010 survey. Prev. Med. Rep. 18, 101065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101065 (2020).

Elhakeem, A., Cooper, R., Bann, D. & Hardy, R. Childhood socioeconomic position and adult leisure-time physical activity: a systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 12, 92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-015-0250-0 (2015).

Ashida, T., Fujiwara, T. & Kondo, K. Childhood socioeconomic status and social integration in later life: results of the Japan gerontological evaluation study. SSM Popul. Health. 18, 101090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2022.101090 (2022).

Tani, Y. et al. Childhood socioeconomic disadvantage is associated with lower mortality in older Japanese men: the JAGES cohort study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 45, 1226–1235. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw146 (2016).

Kondo, K. Progress in aging epidemiology in Japan: the JAGES project. J. Epidemiol. 26, 331–336. https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20160093 (2016).

Tamiya, N. et al. Population ageing and wellbeing: lessons from Japan’s long-term care insurance policy. Lancet 378, 1183–1192. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(11)61176-8 (2011).

Koyano, W., Shibata, H., Nakazato, K., Haga, H. & Suyama, Y. Measurement of competence: reliability and validity of the TMIG index of competence. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 13, 103–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-4943(91)90053-s (1991).

Amemiya, A., Fujiwara, T., Murayama, H., Tani, Y. & Kondo, K. Adverse childhood experiences and Higher-Level functional limitations among older Japanese people: results from the JAGES study. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 73, 261–266. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glx097 (2018).

Fujiwara, Y. et al. Longitudinal changes in higher-level functional capacity of an older population living in a Japanese urban community. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 36, 141–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-4943(02)00081-x (2003).

Tani, Y. et al. Childhood socioeconomic status and onset of depression among Japanese older adults: the JAGES prospective cohort study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 24, 717–726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2016.06.001 (2016).

Murayama, H. et al. Long-term impact of childhood disadvantage on Late-Life functional decline among older Japanese: results from the JAGES prospective cohort study. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 73, 973–979. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glx171 (2018).

Oka, K. Reliability and validity of the stages of change for exercise behavior scale among middle-aged adults. Japanese J. Health Promotion. 5, 15–22 (2003).

Du, Z., Sato, K., Tsuji, T., Kondo, K. & Kondo, N. Sedentary behavior and the combination of physical activity associated with dementia, functional disability, and mortality: A cohort study of 90,471 older adults in Japan. Prev. Med. 180, 107879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2024.107879 (2024).

Tani, Y., Fujiwara, T. & Kondo, K. Associations of cooking skill with social relationships and social capital among older men and women in Japan: results from the JAGES. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 20 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054633 (2023).

Saito, M. et al. Development of an instrument for community-level health related social capital among Japanese older people: the JAGES project. J. Epidemiol. 27, 221–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.je.2016.06.005 (2017).

Tani, Y., Sasaki, Y., Haseda, M., Kondo, K. & Kondo, N. Eating alone and depression in older men and women by cohabitation status: the JAGES longitudinal survey. Age Ageing. 44, 1019–1026. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afv145 (2015).

Tomata, Y. et al. Predictive ability of a simple subjective memory complaints scale for incident dementia: evaluation of Japan’s National checklist, the Kihon checklist. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 17, 1300–1305. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12864 (2017).

Emsley, R. & H., L. PARAMED: Stata module to perform causal mediation analysis using parametric regression models., (2013). https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s457581.html.

Rittsteiger, L. et al. Sports participation of children and adolescents in Germany: disentangling the influence of parental socioeconomic status. BMC Public. Health. 21, 1446. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11284-9 (2021).

Zhang, X., Browning, M., Luo, Y. & Li, H. Can sports cartoon watching in childhood promote adult physical activity and mental health? A pathway analysis in Chinese adults. Heliyon 8, e09417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09417 (2022).

Ono, Y., Tomozoe, H. & Nemoto, S. A study of the formation process of sports recommendation admissions to universities in Japan. Japan J. Phys. Educ. Hlth Sport Sci. 62, 599–620 (2017). (in Japanese).

Bailey, R., Hillman, C., Arent, S. & Petitpas, A. Physical activity: an underestimated investment in human capital? J. Phys. Act. Health. 10, 289–308. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.10.3.289 (2013).

Ludyga, S., Gerber, M., Pühse, U., Looser, V. N. & Kamijo, K. Systematic review and meta-analysis investigating moderators of long-term effects of exercise on cognition in healthy individuals. Nat. Hum. Behav. 4, 603–612. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0851-8 (2020).

Noble, K. G. et al. Family income, parental education and brain structure in children and adolescents. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 773–778. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3983 (2015).

Tooley, U. A., Bassett, D. S. & Mackey, A. P. Environmental influences on the Pace of brain development. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 22, 372–384. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-021-00457-5 (2021).

Ward, M. M. Concordance of sibling’s recall of measures of childhood socioeconomic position. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 11, 147. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-1471471-2288-11-147 (2011). [pii].

Japan Sports Agency. Guidelines on Sports Club Activities (Japan Sports Agency, 2018). (in Japanese).

Funding

This work was supported by the JSPS (Japan Society for the Promotion of Science) KAKENHI (grant numbers JP15H01972, 22K10578, 21H04848, 21K18294), a Health Labour Sciences Research Grant (H28-Choju-Ippan-002), the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (JP18dk0110027, JP18ls0110002, JP18le0110009, JP20dk0110034, JP21lk0310073, JP21dk0110037, JP22lk0310087), Open Innovation Platform with Enterprises, Research Institute and Academia (OPERA, JPMJOP1831), a grant from the Innovative Research Program on Suicide Countermeasures (1–4), a grant from Sasakawa Sports Foundation, a grant from the Japan Health Promotion & Fitness Foundation, a grant from the Chiba Foundation for Health Promotion & Disease Prevention, the 8020 Research Grant for fiscal year 2019 from the 8020 Promotion Foundation (adopted number: 19-2-06), grants from Meiji Yasuda Life Foundation of Health and Welfare and Research Funding for Longevity Sciences from the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology (29–42, 30 − 22, 20 − 19, 21 − 20). This study was also supported by a grant-in-aid from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (22FA2001, 22FA1010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.T., T.F., M.Y. and K.K. have substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of funding, data and interpretation of data; Y.T. analyzed the data; Y.T. and M.Y. drafted the article; T.F. revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The JAGES protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee in Research of Human Subjects at the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology (No. 992) and Chiba University Faculty of Medicine (No. 2493). All methods were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tani, Y., Fujiwara, T., Yamakita, M. et al. Childhood sports club experiences mitigate the association between childhood socioeconomic disadvantage and functional disability in older Japanese men. Sci Rep 15, 14371 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98975-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98975-0