Abstract

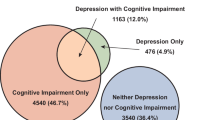

This study aims to evaluate the independent and interactive effects of multimorbidity and cognitive impairment on depressive symptoms among older adults in China. Employing a cross-sectional design, the study collected data from 10,369 individuals aged 65 and above across 35 communities/villages in China. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), cognitive function was evaluated with the Alzheimer’s Disease-8 (AD-8) scale, and chronic disease conditions were recorded. The results indicated that older adults with multimorbidity (OR = 2.481, 95% CI: 2.117, 2.908) and those at high risk of cognitive impairment (OR = 5.469, 95% CI: 4.644, 6.441) exhibited a higher likelihood of experiencing depressive symptoms. Further interaction analysis revealed that, after controlling for confounding factors, no significant multiplicative interaction was found between multimorbidity and cognitive impairment (P = 0.581); however, a significant additive interaction effect was observed (OR = 13.809, 95% CI: 11.063, 17.237). These findings suggest that multimorbidity and cognitive impairment are important factors associated with depressive symptoms in older adults, and their combined presence is linked to a substantially increased likelihood of experiencing depressive symptoms compared to either condition alone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the intensification of global population aging, health issues among older adults have become a significant public health challenge worldwide. Depression, characterized by persistent low mood, loss of interest in daily activities, and low energy levels, is one of the most common psychological disorders among older adults1. It has a high prevalence and far-reaching consequences, not only reducing quality of life but also increasing the burden on healthcare systems. According to the Burden of Disease in the Chinese Population from 2005 to 2017, depression ranks second among non-fatal conditions contributing to disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in China, highlighting its substantial impact on public health and socioeconomic development2.

China is one of the fastest-aging countries in the world, with the proportion of the population aged 65 and older continuously increasing. Based on data from the 2020 Seventh National Population Census, the population aged 65 and above reached 190.64 million, accounting for 13.5% of the total population3. Of particular concern is the high prevalence of depression among older adults in China. The lifetime prevalence of depression is 7.8% for individuals aged 50–64 and 7.3% for those aged 65 and older, rates that exceed those observed in younger age groups4. This high prevalence not only significantly impairs the well-being of older adults but also leads to severe health outcomes, including further reductions in quality of life5.

Early identification and intervention of depressive symptoms are crucial for improving the overall health of older adults. However, the occurrence of depression is often intertwined with multiple complex factors, among which multimorbidity and cognitive impairment—two common health issues in older adults—are particularly noteworthy. Multimorbidity, which refers to the coexistence of two or more chronic diseases, has been widely demonstrated to be closely related to an increased risk of depressive symptoms in older adults6,7,8,9,10. Similarly, cognitive impairment, a common neuropsychological issue, is also thought to increase the likelihood of depression11,12,13.

Despite these insights, current research primarily focuses on the individual effects of multimorbidity or cognitive impairment on depressive symptoms in older adults, with limited exploration of their interaction. Moreover, most studies are based on hospital-based or single-region samples, lacking large-scale community samples that encompass both urban and rural older populations. Especially among older adults in the southwestern region of China, relevant research is even more limited. Therefore, current studies do not fully explain the combined effects of multimorbidity and cognitive impairment on depressive symptoms, nor do they provide sufficient empirical evidence to support regional health policies for older adults.

This study targets the older adults in communities of the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China, employing a multicenter cross-sectional research design to explore the independent and interactive effects of multimorbidity and cognitive impairment on depressive symptoms. By analyzing the interaction mechanisms between these two common health issues, the study aims to investigate how multimorbidity and cognitive impairment are associated with depressive symptoms. The research results not only provide a theoretical basis for developing more targeted early intervention measures and personalized treatment plans but also lay the foundation for improving the mental health and quality of life of older adults. Furthermore, based on empirical analysis from a large-scale urban and rural sample, the study will offer scientific support for the formulation of local health policies and intervention strategies and serve as a reference for similar research and practice in other regions.

The objectives of this study are to:

(1) Investigate the independent effects of multimorbidity and cognitive impairment on depressive symptoms in community-dwelling older adults;

(2) Analyze the combined impact of the interaction between multimorbidity and cognitive impairment on depressive symptoms in older adults.

Materials and methods

Description of the sample

The data for this study originated from the Older Adults’ Mental Health Care Initiative implemented as part of China’s “14th Five-Year Plan” for Healthy Aging. This initiative was launched by the National Health Commission of China, aiming to offer psychological care services for older adults in both urban and rural areas. From September to November 2022, the project team conducted a survey and assessment of the cognitive and mental health status of permanent residents aged 65 and above in 35 communities across 14 cities in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China. A total of 11,583 older adults were involved in this study. During the data preprocessing stage, we addressed missing data in three key categories: chronic disease status, depressive symptoms, and cognitive function. Participants with missing data were excluded, and this portion accounted for 10.5% of the total surveyed subjects. After a strict data-cleaning process, ultimately 10,369 participants (89.5% of the total sample) were incorporated into the data analysis of this study.

Description of the variables

Measurement of multimorbidity

The questionnaire design in this study required participants to report whether they had ever been diagnosed with the following chronic diseases by a doctor: (1) hypertension; (2) heart disease/coronary heart disease; (3) diabetes; (4) cerebrovascular disease (including stroke); (5) chronic bronchitis/other respiratory diseases; (6) cancer/malignant tumors; (7) kidney disease (excluding tumors or cancer); (8) liver disease (excluding fatty liver, tumors or cancer); (9) gastroenteritis or other digestive tract diseases; (10) tuberculosis; (11) rheumatoid arthritis/arthritis; (12) cervical/lumbago; (13) reproductive system diseases; (14) prostate diseases; (15) urinary system diseases; (16) glaucoma or cataract; (17) osteoporosis; (18) deafness. This list of chronic diseases was determined based on previous epidemiological studies and the national disease surveillance focus, and reflects the diseases that are a priority in national health monitoring and prevention strategies12. To avoid potential overlap with the measurement of cognitive impairment and depressive symptoms, neurological diseases (such as Alzheimer’s disease, cerebral atrophy, Parkinson’s disease) and emotional/psychological problems were excluded from the definition of multimorbidity in this study.

In the study, the total number of chronic diseases reported by participants was calculated, and this result was used as the dependent variable. Specifically, if a participant was diagnosed with at least two non-communicable chronic diseases by a doctor, it was considered that they had multimorbidity (no = 1 or fewer, yes = 2 or more).

Measurement of cognitive impairment

We employed the Ascertain Dementia-8 (AD-8), a validated informant-reported scale, to screen for cognitive impairment through structured interviews with primary caregivers. Designed for community-based dementia screening, the AD-8 demonstrates high sensitivity (93.9%) and specificity (76.0%) in detecting mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia among Chinese older adults when using the ≥ 2 cut-off14. The AD-8 is a brief and easy-to-administer tool that is well-suited for use in community settings, primary healthcare facilities, and general medical practice, where specialized neuropsychological assessments may not be readily available. Due to its simplicity, sensitivity, and feasibility, it has been widely applied in clinical trials, epidemiological studies, and community-based cognitive health assessments15. It evaluates decline in eight cognitive domains, including memory, judgment, daily activities, initiative, orientation, visuospatial skills, and recall ability. Each item is scored as 0 (no change) or 1 (decline observed), with a total score ranging from 0 to 8. A score of ≥ 2 suggests possible cognitive impairment16.

Measurement of depressive symptoms

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) is an effective scale for assessing depressive symptoms based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-V. It measures participants’ depressive symptoms over the past two weeks and scores 9 items from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day), with a total score of 27. A score of ≥ 5 indicates the presence of depressive symptoms17.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) version 26.0 for Windows and R 4.3.3. Categorical variables were described statistically by rate and composition ratio (%). The chi-square test was used for group comparisons. Multivariate logistic regression was used to analyze the influencing factors of depressive symptoms. Model 1 and Model 2 were unadjusted and adjusted conditional logistic regression models, respectively, used to analyze the effects of cognitive impairment and multimorbidity on depressive symptoms. The analysis of multiplicative and additive interaction was conducted through R software. The evaluation criteria for additive interaction include relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI), attributable proportion due to interaction (API), and synergy index (SI). If there is an additive interaction, the 95%CI of RERI and API do not include 0, and the 95%CI of SI does not include 118. The significance level is α = 0.05 (two-sided).

Ethical statements

The research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University (Reference No. 2023-KY0905). Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Result

This study collected a total of 11,583 questionnaires, excluding 1214 invalid questionnaires, and obtained 10,369 valid questionnaires, with an effective recovery rate of 89.5%. Among the 10,369 community older adults, there were 4590 men (44.3%) and 5779 women (55.7%). 2607 people (25.1%) reported high-risk levels of cognitive impairment, and 3160 people (30.5%) had at least two chronic diseases. The distribution of depression among community-dwelling older adults differed significantly across various demographic and health-related factors, including Age, Residence, Gender, Marital status, Living conditions, Whether multimorbidity and the Cognitive impairment (P < 0.001). See Table 1.

Among the 18 surveyed chronic diseases, the three most prevalent were hypertension (37.5%), cervical/lumbago (15.5%), and rheumatoid arthritis/joint (10.7%). The prevalence rates of the remaining 15 diseases were all below 10%. See Table 2.

The results indicated that depressive symptoms were more prevalent among older adults with multimorbidity (OR = 2.481, 95% CI: 2.117, 2.908). Similarly, individuals at high risk of cognitive impairment exhibited a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms compared to those with normal cognitive function (OR = 5.469, 95% CI: 4.644, 6.441). See Table 3.

The results of the multiplicative interaction analysis showed that, both before and after adjusting for covariates, no significant multiplicative interaction was observed between multimorbidity and high risk of cognitive impairment in relation to depressive symptoms (P > 0.05). In contrast, the additive interaction analysis suggested that multimorbidity and high risk of cognitive impairment were associated with an additive interaction in relation to depressive symptoms, both before and after adjustment, with RERI values of 6.307 and 6.435, AP values of 0.449 and 0.466, and S values of 1.937 and 2.010. Additionally, multivariate logistic regression analysis indicated that community-dwelling older adults with both multimorbidity and high risk of cognitive impairment had an OR of 13.809 (95% CI: 11.063, 17.237) for depressive symptoms compared to those without multimorbidity and with normal cognitive function. See Table 4.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that both multimorbidity and cognitive impairment are associated with a higher likelihood of depressive symptoms in older adults, with evidence of a significant additive interaction between the two.

The relationship between multimorbidity and depression

Our findings suggest that depressive symptoms are more prevalent among older adults with multimorbidity. Among all participants, 12.8% of those with multimorbidity reported depressive symptoms, compared to 4.7% of those without multimorbidity. Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that older adults with multimorbidity had 2.481 times higher odds of experiencing depressive symptoms compared to those without multimorbidity (OR = 2.481, 95% CI: 2.117, 2.908). This finding is consistent with previous studies, which have reported an association between multimorbidity and an increased likelihood of depressive symptoms19. The underlying mechanisms may involve physical discomfort, treatment burden, and financial strain associated with multiple chronic conditions, as well as potential biological pathways such as chronic inflammation and oxidative stress, which may impact emotional regulation20,21,22.

The relationship between cognitive impairment and depression

Our findings suggest that depressive symptoms are more prevalent among older adults at high risk of cognitive impairment. The incidence of depressive symptoms in this group was 18.4%, significantly higher than the 3.4% observed in those with normal cognitive function. Logistic regression analysis indicated that older adults at high risk of cognitive impairment had 5.469 times higher odds of experiencing depressive symptoms compared to those with normal cognitive function (OR = 5.469, 95% CI: 4.644, 6.441). This finding is consistent with previous research, which has reported an association between cognitive impairment and an increased likelihood of depressive symptoms11.

Several potential mechanisms may underlie this association. One hypothesis is that sleep disturbances may mediate the relationship between cognitive impairment and depressive symptoms, while cognitive theories of depression suggest that deficits in cognitive processing contribute to emotional dysregulation23. Additionally, cognitive impairment may be linked to depressive symptoms through three key mechanisms: impaired inhibitory control and working memory deficits, persistent rumination on negative emotions and experiences, and reduced efficiency in regulating negative emotions. Somatic symptoms of depression, such as fatigue and attention deficits, may also serve as early indicators of cognitive decline23. Furthermore, a collaborative study by the Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences found that the severity of depression was associated with neurological markers of cognitive dysfunction, suggesting that cognitive impairment may influence emotional regulation, thereby increasing susceptibility to depressive symptoms24.

The interaction between multimorbidity and cognitive impairment

Interaction effects and their implications

The interaction effects include multiplicative and additive models. The multiplicative interaction mainly reflects the association at the statistical level, while the additive interaction shows higher value in practical applications25. By analyzing the additive interaction, the effect differences among different subgroups can be measured more precisely, thereby effectively identifying high-risk populations. Our study explored the combined effects of multimorbidity and cognitive impairment on depressive symptoms in older adults. The results showed that while multimorbidity and cognitive impairment did not exhibit a statistically significant multiplicative interaction (P = 0.581), a significant additive interaction was observed. Older adults with both multimorbidity and cognitive impairment had significantly higher odds of experiencing depressive symptoms (OR = 13.809, 95% CI: 11.063, 17.237) compared to those with either condition alone (OR = 2.633, 95% CI: 2.052, 3.378 for multimorbidity only; OR = 5.742, 95% CI: 4.569, 7.216 for cognitive impairment only). These findings suggest that the co-occurrence of multimorbidity and cognitive impairment is associated with a substantially elevated likelihood of depressive symptoms, highlighting the need for integrated screening and intervention strategies.

Potential mechanisms of additive interaction

The observed additive interaction may arise from interconnected biological and psychosocial pathways.

Multimorbidity is often accompanied by chronic low-grade inflammation (e.g., elevated IL-6, CRP), which may contribute to blood-brain barrier dysfunction, accelerating amyloid-β deposition and neuronal injury26,27. This process could exacerbate both cognitive decline and mood dysregulation by disrupting prefrontal-limbic circuitry. Conditions such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease are linked to dysregulated hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activity, which may further impair hippocampal neurogenesis28,29.

Multimorbidity often necessitates complex medication regimens and frequent medical visits, which may tax cognitive reserves needed for emotional regulation30. Cognitive impairment, in turn, may reduce problem-solving capacity, prolonging stress exposure and increasing vulnerability to depression.32 The combined effects of physical and cognitive limitations (e.g., mobility restrictions, communication difficulties) may reduce social engagement, which serves as a protective factor against depression. The resulting social withdrawal may establish a self-reinforcing cycle of cognitive and emotional decline31.

Implications for prevention and intervention

To address the combined burden of multimorbidity and cognitive impairment on depressive symptoms in older adults, a multifaceted approach is required. The following strategies may enhance early detection, intervention, and healthcare system integration:

Individuals at high risk for both conditions should be automatically referred for PHQ-9 depression assessment. Prioritize implementation in rural health centers, particularly in Southwest China, where ethnic minority populations and fragmented healthcare access may heighten vulnerability32.

Evaluate the effectiveness of anti-inflammatory lifestyle interventions (e.g., omega-3 supplementation, mindfulness-based stress reduction) in populations experiencing both multimorbidity and cognitive impairment, as these strategies may mitigate inflammation-related cognitive and emotional decline33,34. Adapt the WHO’s Integrated Care for Older People (ICOPE) framework by incorporating cognitive and mood assessment modules into routine chronic disease management programs.

Incorporate additive interaction metrics (e.g., RERI, Synergy Index) into China’s Healthy Aging 2030 monitoring framework to optimize resource allocation for high-risk populations. Establish multidisciplinary geriatric teams (e.g., primary care physicians, neurologists, psychiatrists) in regions with high prevalence of multimorbidity and cognitive impairment, such as Guangxi.

Influence of other sociodemographic characteristics

In addition to health status, this study also found that sociodemographic factors such as gender, place of residence, marital status, and living conditions have significant effects on depressive symptoms. For instance, the prevalence of depressive symptoms was significantly higher among females than males (OR = 1.270, 95% CI: 1.067, 1.513), which may be related to differences in psychosocial stress, societal role expectations, and physiological changes in females35. Furthermore, older adults residing in rural areas exhibited a higher likelihood of depressive symptoms (OR = 1.441, 95% CI: 1.229, 1.689), possibly due to limited access to healthcare and mental health services, as well as greater social isolation36,37. Additionally, the shortage of medical resources in these areas may contribute to delays in the detection and treatment of depression38,39.Widowed individuals were also more likely to report depressive symptoms compared to those who were married (OR = 1.239, 95% CI: 1.027, 1.496), which aligns with previous findings37,40. As spouses and co-residents often serve as primary sources of social support, their absence may contribute to emotional distress. This may partly explain why older adults who are widowed or live alone tend to report more depressive symptoms41.

Limitations and future directions of the study

This study has several limitations. First, due to its cross-sectional design, it does not establish causality. Therefore, while multimorbidity and cognitive impairment were found to be associated with depressive symptoms, it remains unclear whether they directly contribute to depression. Future research could employ longitudinal designs to better explore these relationships. Second, the study sample was exclusively drawn from community-dwelling older adults in the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China. To enhance external validity, future studies should validate these findings in diverse geographic regions and populations. Third, although we considered multiple health-related indicators, some important factors influencing depressive symptoms, such as quality of life and social support, were not included. Future research should incorporate these aspects for a more comprehensive analysis. Additionally, this study used the AD-8 as a cognitive impairment screening tool, which is effective for detecting early cognitive decline but has certain limitations. As a caregiver-reported tool, the AD-8 may be subject to subjective bias and does not provide detailed assessments of specific cognitive domains such as attention, language, or executive function. Future studies should consider incorporating more comprehensive cognitive assessments, such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) or the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), to improve the accuracy and reliability of cognitive function measurement.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that multimorbidity and cognitive impairment are significantly associated with depressive symptoms in older adults, and an additive interaction exists between these two factors. Older adults with both multimorbidity and cognitive impairment exhibited a notably higher likelihood of experiencing depressive symptoms compared to other groups. Therefore, in efforts to prevent and manage depression in older adults, particular attention should be given to individuals with coexisting multimorbidity and cognitive impairment. These findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the potential risk factors for late-life depression and provide valuable insights for the early identification and targeted intervention of depressive symptoms in this population.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhao, Y., Mai, H. & Bian, Y. Associations between the number of children, depressive symptoms, and cognition in middle-aged and older adults: Evidence from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Healthc. Basel Switz. 12(2024) (1928).

Peng, Y. et al. Burden of disease in the Chinese population from 2005 to 2017. Chin. Circ. J. 34, 1145–1154 (2019).

Akimov, A. V. et al. The seventh population census in the PRC: results and prospects of the country’s demographic development. Her Russ Acad. Sci. 91, 724–735 (2021).

Lu, J. et al. Prevalence of depressive disorders and treatment in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry. 8, 981–990 (2021).

Li, A. et al. Depression and life satisfaction among Middle-Aged and older adults: mediation effect of functional disability. Front. Psychol. 12, 755220 (2021).

Skou, S. T. et al. Multimorbidity. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 8, 1–22 (2022).

Wu, J. et al. Healthcare for older adults with Multimorbidity: A scoping review of reviews. Clin. Interv Aging. 18, 1723–1735 (2023).

Zhong, Y. et al. Prevalence, patterns of Multimorbidity and associations with health care utilization among middle-aged and older people in China. BMC Public. Health. 23, 537 (2023).

Organization, W. H. Multimorbidity (World Health Organization, 2016).

Zhao, X. et al. Prevalence of subthreshold depression in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian J. Psychiatry. 102, 104253 (2024).

Guo, H. et al. Sleep quality partially mediate the relationship between depressive symptoms and cognitive function in older Chinese: A longitudinal study across 10 years. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 15, 785–799 (2022).

Lai, L. et al. Depressive symptom mediates the association between the number of chronic diseases and cognitive impairment: a multi-center cross-sectional study based on community older adults. Front. Psychiatry. 15, 1404229 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. The mediation role of sleep quality in the relationship between cognitive decline and depression. BMC Geriatr. 22, 178 (2022).

Li, T. et al. The reliability and validity of Chinese version of AD8. Chin. J. Intern. Med. 51, 777–780 (2012).

Cai, M. et al. Strategy for the choice of appropriate mild cognitive impairment screening scales for Community-dwelling older adults. Chin. Gen. Pract. 25, 3191–3195 (2022).

Mayà, G. et al. Assessment of cognitive symptoms in brain Bank-Registered control subjects: feasibility and utility of a Telephone-Based screening. J. Alzheimers Dis. JAD. 85, 1107–1113 (2022).

Wang, J., Chen, S. & Xue, J. Depressive symptoms mediate the longitudinal relationships between sleep quality and cognitive functions among older adults with mild cognitive impairment: A cross-lagged modeling analysis. Sci. Rep. 14, 21242 (2024).

VanderWeele, T. J. & Knol, M. J. A tutorial on interaction. Epidemiol. Methods. 3, 33–72 (2014).

Lin, W. et al. Analysis of depression status and influencing factors in middle-aged and elderly patients with chronic diseases. Front. Psychol. 15, 1308397 (2024).

Zhou, Y. et al. Bidirectional associations between cardiometabolic Multimorbidity and depression and mediation of lifestyles: A multicohort study. JACC Asia. 4, 657–671 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Longitudinal association of sleep duration with depressive symptoms among Middle-aged and older Chinese. Sci. Rep. 7, 11794 (2017).

Lee, J., Kim, S. Y. & Lee, K. S. The mediating role of depressive symptoms and treatment burden on Health-Related quality of life among multimorbid patients with hypertension: A Multi-Group analysis. Nurs. Health Sci. 26, e13176 (2024).

Gotlib, I. H. & Joormann, J. Cognition and depression: current status and future directions. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 6, 285–312 (2010).

Li, D. et al. Neurophysiological markers of disease severity and cognitive dysfunction in major depressive disorder: A TMS-EEG study. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. IJCHP. 24, 100495 (2024).

Diaz-Gallo, L. M. et al. Understanding interactions between risk factors, and assessing the utility of the additive and multiplicative models through simulations. PLoS ONE. 16, e0250282 (2021).

Friedman, E. & Shorey, C. Inflammation in Multimorbidity and disability: an integrative review. Health Psychol. Off J. Div. Health Psychol. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 38, 791–801 (2019).

Erickson, M. A. & Banks, W. A. Neuroimmune axes of the Blood–Brain barriers and Blood–Brain interfaces: bases for physiological regulation, disease States, and Pharmacological interventions. Pharmacol. Rev. 70, 278–314 (2018).

Joseph, J. J. & Golden, S. H. Cortisol dysregulation: the bidirectional link between stress, depression, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 1391, 20–34 (2017).

Dampney, R. A. L. Central neural control of the cardiovascular system: current perspectives. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 40, 283–296 (2016).

Zhao, Y. W. et al. The effect of Multimorbidity on functional limitations and depression amongst middle-aged and older population in China: a nationwide longitudinal study. Age Ageing. 50, 190–197 (2021).

Zhao, D. et al. Physical mobility, social isolation and cognitive function: are there really gender differences?? Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 31, 726–736 (2023).

Wang, Z. et al. Health resource allocation in Western China from 2014 to 2018. Arch. Public. Health Arch. Belg. Sante Publique. 81, 30 (2023).

Marinovic, D. A. & Hunter, R. L. Examining the interrelationships between mindfulness-based interventions, depression, inflammation, and cancer survival. CA Cancer J. Clin. 72, 490–502 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Intakes of fish and polyunsaturated fatty acids and mild-to-severe cognitive impairment risks: a dose-response meta-analysis of 21 cohort studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 103, 330–340 (2016).

Corneliusson, L., Gustafson, Y. & Olofsson, B. Prevalence of depressive disorders among the very old in the 21st century. J. Affect. Disord. 362, 706–715 (2024).

Xia, Y., Wang, G. & Yang, F. A nationwide study of the impact of social quality factors on life satisfaction among older adults in rural China. Sci. Rep. 14, 11614 (2024).

Ting, Y. et al. Current status of depressive symptoms and their influencing factors among elderly Chinese residents. Mod. Prev. Med. 48, 3461–3465 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. Digital mental health in China: a systematic review. Psychol. Med. 51, 2552–2570 (2021).

Bradford, N. et al. Telehealth services in rural and remote Australia: a systematic review of models of care and factors influencing success and sustainability. Rural Remote Health. 16, 3808 (2016).

Wang Yue, C. Q. Detection rate of depression and its influencing factors in Chinese elderly: a Meta-analysis. Chin. Gen. Pract. 26, 4329 (2023).

Acoba, E. F. Social support and mental health: the mediating role of perceived stress. Front. Psychol. 15, 1330720 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Health Commission of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region: Elderly Nutrition Improvement Action Project of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University (2024004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.D. conceptualized and designed the study, performed the data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. H.W., Y.C., P.H., D.H., L.L., J.P., X.C., and X.F. contributed to data collection and initial data preprocessing. H.H. supervised the research process, guided the methodology, and reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, P., Wu, H., Chai, Y. et al. Impact of multimorbidity and cognitive impairment on depressive symptoms in community-dwelling older adults and their interaction effects. Sci Rep 15, 15033 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99547-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99547-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Association between multimorbidity and childhood socioeconomic status with depressive symptoms among middle-aged and older adults in rural western China

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

The relationship between cognitive impairment and quality of life in rural older adults with chronic diseases—parallel mediating effects of depressive symptoms and frailty

BMC Geriatrics (2025)