Abstract

Gastrodia elata Blume (G. elata Bl.) is a dual-purpose herb for medicine and food. Wild resources are depleted, and there is a significant decrease in yield or quality when they are cultivated artificially. However, what factors led to the decline is still unclear. In this study, based on comprehensive data under multiple production regions, hierarchical partitioning and partial least squares path modeling were used for the first time to quantitatively evaluate the dominant influencing factors and mechanism for the yield and quality of cultivated G. elata Bl.. The results showed that all G. elata Bl. were categorized into two cultivated subspecies G. elata Bl. f. elata and G. elata Bl. f. glauca. The Proteobacteria was the most dominant phylum for bacteria with 33.59%, and Ascomycota for fungi with 46.33% based on the amplicon sequencing. Armillaria relative abundance, soil available potassium, and temperature seasonality were the key factors. Their independent effects were 74.14%, 24.78%, and 20.36% on yield, and 36.83%, 25.63%, and 21.30% on quality, respectively. Plant subspecies directly determined the yield and quality (P < 0.01). Soil physical properties affected chemical properties, which in turn affected biological properties and ultimately yields (P < 0.05). Meanwhile, soil physical properties affected quality by influencing soil chemical properties (P < 0.01). In conclusion, our study contributed novel insight to optimize cultivation strategies of G. elata Bl..

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

G. elata Bl. is a perennial herb in Orchidaceae, with a wide geographical range in China, Japan, Korea, Bhutan, and India, which is both an important medicinal plant and a popular traditional food1. Its dried tubers, Gastrodiae Rhizoma (also known as Tianma in Chinese), are often used as valuable traditional Chinese medicines2. Modern pharmacological studies have proved that isolated components or crude extracts of G. elata Bl. possess neuroprotection, learning and memory improvement effects, cardioprotection, vasomodulatory effects, anti-depression, anti-cancer, and other activities3,4,5,6. Due to immense medicinal value, high market demand, and over-excavation7, G. elata Bl. has been included in the list of rare and endangered plants, and cultivated G. elata Bl. has become the main source of obtaining them8. However, there is a significant decrease in yield or quality when they are cultivated artificially9.

The yield and quality of G. elata Bl. are greatly influenced by genetic and environmental factors. As one of the heterotrophic plants without chlorophyll, the growth and development of G. elata Bl. require symbiosis with Armillaria and Mycena10,11,12,13. Among them, the fungi belonging to the genus Armillaria imposed a significant impact on the yield of G. elata Bl.14. At the same time, there are great differences in the content of active components in different plant subspecies15. For instance, G. elata Bl. f. viridis was found to have a higher total sugar content than G. elata Bl. f. glauca and G. elata Bl. f. elata16. Compared with the population from Yunnan Province, the population from Guizhou Province has a higher gastrodin (GAS) content17. In addition, soil properties also affect the yield and quality of G. elata Bl.. Soil physical properties are the main aspects affecting soil chemical properties18, and they together emerge as key drivers of microbiome structure and microbial activities19. Furthermore, altitude can affect the water content of fresh tubers of G. elata Bl., which in turn affects its quality20. Low temperature treatment can promote a stable production of immature rhizomes by breaking dormancy21. When the temperature is 20–25 °C, it is beneficial to the development of protocorm in vitro in the achlorophyllous orchid Gastrodia pubilabiata Sawa22.

Although these findings emphasize their important roles in the formation of yield and quality of G. elata Bl. from single aspects such as plant materials, soil properties, and climatic factors, under actual cultivation conditions, the yield and quality of G. elata Bl. can be affected by both plant material, soil properties, and climatic factors23. Moreover, their influences on the yield and quality of G. elata Bl. are extremely complex24. However, few studies have linked plant materials, soil properties, and climatic factors to explore the independent effects as well as their interaction on the yield and quality of G. elata Bl. Therefore, this study aimed to: (1) quantify the independent and interactive contributions of plant subspecies, soil properties (physical, chemical, biological), and climatic factors to G. elata Bl. yield and quality; (2) identify dominant drivers using hierarchical partitioning (HP) and elucidate mechanistic pathways via partial least squares path modeling (PLS-PM); and (3) propose targeted strategies to optimize cultivation.

To achieve these objectives, seven representative environments in China with prominent G. elata Bl. production were selected to collect tubers and soil. Based on the HP and PLS-PM, plant subspecies, soil physical properties, soil chemical properties, soil biological properties, temperature, precipitation, and altitude were evaluated and analyzed simultaneously. The present paper not only comprehensively identified the significant factors affecting the yield and quality of G. elata Bl. for the first time, but also further clarified the mechanism of these influencing factors. The research findings could offer a theoretical foundation for the breeding of G. elata Bl., and provide valuable insights for improving the yield and quality of G. elata Bl. and achieving large-scale greenhouse cultivation.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

Seven representative environments (named GSKX, GZDF, HBYL, SCPW, SXLY, YNYL, and YNZX) with prominent G. elata Bl. production (geo-authentic product region) were selected to collect healthy tubers at harvest (Table S1). All G. elata Bl. samples used in this study were derived from cultivated sources and provided by Guizhou Jiulong Tianma Co. Ltd. (GZDF, Bijie, China), Pingwu Simiao Technology Development Co., Ltd. (SCPW, Mianyang, China), and five individuals from GSKX, HBYL, SXLY, YNYL, and YNZX. These samples were identified as G. elata Bl. by Professor Hong Jin, School of Pharmacy, Sichuan College of Traditional Chinese Medicine. The authors adhered to the guidelines of the WHO guidelines on good agricultural and collection practices (GACP) for medicinal plants (https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/42783/9241546271.pdf?sequence=1) and the Good Agricultural Practices for Chinese Crude Drugs (https://english.nmpa.gov.cn/2022-03/17/c_772359.htm) during the plant collection process. The voucher specimens were stored under the number SCTCM-20231211 at the School of Pharmacy, Sichuan College of Traditional Chinese Medicine. The sampling points were randomly selected in each environment. Removing the topsoil and peripheral soil using a shovel, the tubersphere soil was pooled into 50 mL sterile tubes from 1 cm away from the tuber. The soil was sieved through a 2 mm sieve after removing debris and stored at −80 °C. The sample collection was discontinuously conducted between October and November 2023 (Table S1). Before the sample collection, there had been no rain in the environments for at least one week. A total of 21 G. elata Bl. samples and their soil were collected. Meanwhile, locality and GPS data of each sampling point were obtained (Table S1).

Evaluation of yield and quality

After completing the collection of soil and G. elata Bl. samples, all G. elata Bl. tubers were collected within 1 square meter of each sampling point and were weighed for assessment of the yield of G. elata Bl. Fresh single G. elata Bl. were cleaned with water and steamed based on single tuber fresh weight (Table S2). After steaming at atmospheric pressure, G. elata Bl. tubers were cut lengthwise into 2 mm thick slices and were dried at 50 °C for 4 h until the water content was less than 15%. Each G. elata Bl. sample was powdered and passed through a 0.355 mm sieve. Water content before high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis was measured after drying at 105 °C for 10 min. The contents of GAS and p–hydroxybenzyl alcohol (HBA) were detected and calculated based on the methods in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia 202025. The standard samples were purchased from Sichuan Weikeqi Biological Technology Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, China).

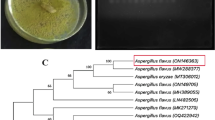

G. elata Bl. subspecies identification and phylogenetic analysis

DNA was extracted from the arrow shoot of G. elata Bl. Six DNA fragments were selected as DNA barcoding26,27,28,29,30,31, including ITS, ITS2, rbcL, matK, psbA–trnH, and trnL–F (Table S3). A final volume of 25 µL was amplified, containing 2 µL of genomic DNA, 12.5 µL of 2×Taq RCR Master Mix, 1.0 µL of each primer, and 8.5 µL of distilled deionized water. The amplicons of six DNA barcodings were sequenced bidirectionally on SANGER ABI3730XL (Tsingke Biotech Co., Ltd., Chengdu, China). The peak map was spliced by Contig Express version 3.0 (Codon Code Co., USA), and then the primer region and low region were removed. The hidden Markov models was used to remove the 5.8 S and 28 S segments to obtain the ITS2 sequences32. The final ITS2 sequence has been transmitted to the GenBank database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank), and all sequence names and the accession numbers were listed in Table S4. At the same time, other ITS2 sequences of G. elata Bl. were downloaded from the GenBank database. All ITS2 sequences were imported into MEGA 7.0 software. Based on the Kimura2-parameter model, the phylogenetic tree of G. elata Bl. subspecies was constructed by the neighbor–joining method, and the support rate of each branch was tested by bootstrapping 1000 iterations33.

Measurement of soil physical, chemical and biological properties

Soil physical properties are mainly soil particle size, which was measured using a laser particle size analyzer based on the previous report34. The percentages of soil clay (< 0.002 mm), silt (0.002–0.05 mm), and sand (0.05–2 mm) were calculated based on the soil particle size following the United States Department of Agriculture particle size classification system35. In this study, the percentage of clay content was employed as an indicator of soil texture.

To measure soil chemical properties, soil samples were naturally dried, ground, and sieved through a 0.25 mm sieve. The soil organic matter was determined by the oven heating method36. Soil pH was measured based on a soil–to–water ratio of 1:2.5 using a pH meter (F20, Shanghai Mettler-Toledo International Trading Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). Total N, total P, total K, available N, available P, and available K in soil were determined by Sanshu Biotechnology Co., LTD. (Nantong, China) according to the previous literature37,38. Soil moisture content was determined by the drying method, namely, soil samples were dried in an oven at 105 °C until they reached a constant weight, and then SMC was calculated according to the weight change.

For soil biological properties, soil DNA was extracted with PowerSoil®DNA Isolation Kits (MOBIO Laboratories, Carlsbad, California, USA). Amplification and sequencing were performed at Beijing Tsingke Biotech Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The bacterial 16 S rRNA gene V3–V4 region was amplified using universal primers 338 F (5’–ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA–3’) and 806R (5’–GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT–3’), and the fungal ITS1 region was amplified using universal primers ITS1 F (5’–CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA–3’) and ITS2R (5’–GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC–3’). Sequencing of the V3–V4 and ITS1 regions was performed via Illumina NovaSeq 6000 PE250. Raw reads were filtered using Trimmomatic v0.33 software, and clean reads were obtained by identifying and removing primer sequences using Cutadapt v1.9.1 software. The amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were obtained by de–noising using the DADA2 method in QIIME2 software39,40. To conduct taxonomic annotation, the ribosome sequences V3–V4 were aligned to the sequences in the SILVA 138 database (http://www.arbsilva.de), and ITS1 were aligned to the sequences in the UNITE 8.0 database (https://unite.ut.ee/). Colony abundance indexes (Chao1 and Ace) and diversity indexes (Shannon and Simpson) were calculated based on ASVs.

Ecologically suitable analysis

By searching the related literature and major botanical specimen databases (Chinese Virtual Herbarium, http://www.cvh.org.cn/; Global Biodiversity Information Facility, http://www.gbif.org/; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, http://www.kew.org/; Discover Life, http://www.discoverlife.org/), the information was collected on the distribution points of cultivated G. elata Bl. and wild G. elata Bl. in China. Combining with the latitude and longitude obtained from the field surveys of the present study, all distribution points of G. elata Bl. were obtained. Using the Global Medicinal Plant Geographic Information System (GMPGIS)41, the ecological suitability of G. elata Bl. in China was studied to obtain the range of suitability values of its major ecological factors, major soil types, and the regional distribution map of its maximum ecological similarity in China.

Statistical analysis

The data of climatic factors were obtained from the WorldClim database (https://www.worldclim.org/data/bioclim.html#google_vignette), including 11 temperature parameters (bio1–bio11) and eight precipitation parameters (bio12–bio19)42. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.0.243. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess normality before testing for significance, and the homogeneity of variance was analyzed with an F-test. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were conducted to assess the differences in active component content and soil properties in different environments. Pearson correlation was employed to measure the associations among active component content, soil properties, and climatic factors with the “corrplot” package in R44. The HP was performed using the “glmm.hp” package in R45,46. The PLS-PM framework was employed to examine the hypothesized causal connections among active component content, plant subspecies, soil properties, and climatic factors with the “plspm” package in R47. A bootstrap method (1000 iterations) was used to validate the estimates of the path coefficients and the coefficients of determination (R2). Finally, eliminating loading less than 0.7, the goodness-of-fit index was used to evaluate the overall predictive performance of the model48. Figures were drawn with the “ggplot2” package in R49.

Results

The yield and quality of G. elata Bl.

The morphological features of cultivated G. elata Bl. from different environments were depicted in Fig. S1. For the yield of G. elata Bl., it was 13.22 kg/m2, 5.12 kg/m2, 11.80 kg/m2, 5.33 kg/m2, 14.00 kg/m2, 6.64 kg/m2, and 6.50/m2, respectively (Fig. 1). The yields of G. elata Bl. from GSKX, HBYL, and SXLY were significantly higher than GZDF, SCPW, YNYL, and YNZX (P < 0.05). The water content of all samples ranged from 6.97% to 14.73% before HPLC analysis (Table S5), which met the requirements of the Chinese Pharmacopoeia 2020 of less than 15%. For the quality of G. elata Bl., GAS content was 0.28%, 0.39%, 0.31%, 0.46%, 0.34%, 0.56%, and 0.49%, respectively (Fig. 1), which differed significantly between the seven environments (P < 0.05). The content of HBA is 0.10%, 0.08%, 0.01%, 0.09%, 0.03%, 0.08%, and 0.05%, respectively (Fig. 1). The content of HBA from HBYL, SXLY, and YNZX were significantly lower than GSKX, GZDF, SCPW, and YNYL (P < 0.05). The sum of GAS and HBA content was a minimum of 0.32% (HBYL) and a maximum of 0.66% (YNYL, Fig. 1). Similarly, their content met the requirements of the Chinese Pharmacopoeia 2020, that is, the sum of the contents is not less than 0.25%.

G. elata Bl. subspecies and phylogenetic tree

Six DNA markers (ITS, ITS2, rbcL, matK, psbA–trnH and trnL–F) were selected as DNA barcoding in this study. The PCR success rate ranged from 10% to 100% (Fig. S2). Among the six DNA barcodings, only the ITS2 was amplified with a success rate of 100%. Based on ITS2, all G. elata Bl. were categorized into two cultivated subspecies (Fig. 2), including G. elata Bl. f. elata (known as hongtianma in Chinese) and G. elata Bl. f. glauca (known as wutianma in Chinese). The phylogenetic tree of G. elata Bl. was also depicted in Fig. 2. Three G. elata Bl. f. elata from HBYL and eight sequences from the GenBank database were clustered into one group, and its bootstrap support was 100%. Six G. elata Bl. f. elata from SXLY and GSKX were clustered into one group, and its bootstrap support was 80%. Twelve G. elata Bl. f. glauca from SCPW, GZDF, YNZX, and YNYL were clustered into one group, and its bootstrap support was 96%.

Soil physical, chemical and biological properties

The soil texture classification based on the United States Department of Agriculture was depicted in Fig. 3. The highest soil clay content was 33.27% (GSKX), and the lowest is 1.86% (SXLY). The highest soil silt content was 47.17% (YNYL), and the lowest is 17.84% (SXLY). The highest soil sand content was 80.30% (SXLY), and the lowest is 20.77% (YNYL). The soil from SXLY and HBYL belonged to loamy sand. The soil from GZDF, SCPW, and YNZX belonged to loam. The soil from GSKX and YNYL belonged to clay loam.

Nine soil chemical components were detected in this study (Fig. 4), including soil moisture content (SMC), soil pH, soil organic matter (SOM), soil total nitrogen (STN), soil total phosphorus (STP), soil total potassium (STK), soil available nitrogen (SAN), soil available phosphorus (SAP), and soil available potassium (SAK). The results showed that SMC ranged from 10.5% (SXLY) to 39.6% (YNYL), soil pH ranged from 4.5 (SCPW) to 5.9 (SXLY), SOM ranged from 6.6 g/kg (HBYL) to 74.7 g/kg (YNZX), STN ranged from 0.4 g/kg (HBYL) to 3.4 g/kg (YNZX), STP ranged from 0.2 g/kg (SCPW) to 1.1 g/kg (SXLY), STK ranged from 7.0 g/kg (GZDF) to 23.6 g/kg (YNZX), SAN ranged from 0.0296 g/kg (HBYL) to 0.2957 g/kg (YNYL), SAP ranged from 0.0002 g/kg (GSKX) to 0.0125 g/kg (SXLY), and SAK ranged from 0.0854 g/kg (SCPW) to 0.2826 g/kg (GSKX), respectively. There were significant differences in each soil chemical composition among different environments (P < 0.05).

After merging of paired-end raw reads, their quality control, and filtration of chimeric sequences, a total of 969,195 active amplicon sequences were obtained belonging to the 16 S rRNA region. Similarly, a total of 1,259,591 active sequences were obtained for the ITS1 region from 21 soil samples. At a threshold of 0.97, the sequences were clustered to 32,555 ASVs of bacteria and 11,772 ASVs of fungi. A total of 876,732 clean reads of bacteria belonging to 40 phylum and a total of 1,174,888 clean reads of fungi belonging to 19 phylum. The sparse curve of the ASVs gradually fattened out (Fig. S3), which indicated that the sequencing depth covered all the species in the sample.

The taxonomic annotation of ASVs was performed from phylum to species level. For bacteria, Proteobacteria was the most dominant phylum (33.59%), followed by Acidobacteriota (22.51%) and Bacteroidota (6.42%). Approximately 6.17% of ASVs remained unclassified (Fig. 5a). Unclassified bacteria was the dominant genus (6.17%), followed by unclassified Xanthobacteraceae (3.50%) and unclassified Acidobacteriales (2.81%). Approximately 72.34% of ASVs belong to others (Fig. 5b). For fungi, Ascomycota was the most frequent phylum (46.33%), followed by Basidiomycota (22.71%) and Mortierellomycota (12.59%). The unclassified ASVs accounted for up to 6.34% (Fig. 5c). The unidentified was the dominant genus (14.56%), followed by Mortierella (12.50%) and unclassified fungi (6.34%, Fig. 5 d).

In order to clarify the effect of Armillaria and Mycena on the yield and active component content, their relative abundances were detected (Fig. S4). For Armillaria, the relative abundance was 0.78%, 0.08%, 0.66%, 0.16%, 0.94%, 0.30%, and 0.24%, respectively (P < 0.05). For Mycena, only were detected in GZDF, HBYL, YNYL, and YNZX. Their relative abundances were 0.02%, 0.07%, 0.12%, and 0.01%, respectively (P < 0.05).

Colony abundance indexes (ACE index and Chao1 index) and diversity indexes (Shannon index and Simpson index) of bacteria and fungi were depicted in Fig. S5. From the result, in bacteria, the trends of ACE index and Chao1 index were completely consistent. Namely, GZDF, SXLY, and YNYL were significantly higher than SCPW and YNZX (P < 0.05). Meanwhile, GZDF and YNYL had significantly higher Shannon index and Simpson index than the other five environments (P < 0.05). In fungi, the ACE index and Chao1 index were essentially the same as those of the bacteria. SCPW and YNZX had significantly lower Shannon index and Simpson index than the other environments (P < 0.05).

The soil chemical properties in different environments. Different lowercase letters showed significant differences (P < 0.05). SMC represents soil moisture content; SOM represents soil organic matter; STN represents soil total nitrogen; STP represents soil total phosphorus; STK represents soil total potassium; SAN represents soil available nitrogen; SAP represents soil available phosphorus; SAK represents soil available potassium; n = 3.

Ecologically suitable distributions

Using the GMPGIS, 337 distribution points of G. elata Bl. in China were located as far west as Tibet, as far east and north as Jilin, and as far south as Yunnan and Taiwan (Fig. S6). Based on the sampling points of G. elata Bl., the key threshold values of the ecological factors of the species were extracted from the GMPGIS (Table S6). The biological range of annual mean temperature was − 0.3–21.4 °C, the mean diurnal range was 6.5–14.3 °C, temperature seasonality was 2.8–13.4%, annual precipitation was 543.0–2832.0 mm, and precipitation seasonality was 36.0–107.0%. The distribution map of maximum ecological similarity areas of G. elata Bl. in China mainly included Tibet, Sichuan Province, Xinjiang, Yunnan Province, Heilongjiang Province, Inner Mongolia, Qinghai Province, Guizhou Province, Shaanxi Province, etc. (Fig. 6). Especially in Sichuan Province, Yunnan Province, and Guizhou Province, almost the whole province was suitable for cultivation of G. elata Bl..

Relationship among yield, quality, plant subspecies, soil properties and climatic factors

The yield of G. elata Bl. refers to the weight of all G. elata Bl. tubers per unit area, while the quality of G. elata Bl. refers to the weight proportion of active components in dried products. In G. elata Bl., GAS and HBA are the main active components, especially GAS. Therefore, GAS content can represent the quality of G. elata Bl. The HP and PLS-PM were performed using the yield and GAS content. The results of the HP were shown in Fig. 7. For the yield of G. elata Bl., Armillaria relative abundance (ARA), SAK, and BIO4 were the most important influencing factors of soil biological properties, soil chemical properties, and climate factors, with the explained variation of 74.14%, 24.78%, and 20.36%, respectively (Fig. 7a). The R2 for soil biological properties, soil chemical properties, and climate factors were 0.98, 0.74, and 0.97, respectively. When the first three important variables of soil biological properties, soil chemical properties and climate factors were selected, and plant subspecies (PS) and soil texture were added, ARA, PS, and BIO4 were the most important influencing factors, explaining yield variation of 21.22%, 19.41%, and 18.10%, respectively (Fig. 7a). The R2 for the 11 most important variables was 0.97.

For GAS content, ARA, SAK, and BIO4 were also the most important influencing factors of soil biological properties, soil chemical properties, and climate factors, with the explained variation of 36.83%, 25.63%, and 21.30%, respectively (Fig. 7b). The R2 for soil biological properties, soil chemical properties, and climate factors were 0.85, 0.90, and 0.99, respectively. When the first three important variables of soil biological properties, soil chemical properties and climate factors were selected, and PS and soil texture were added, PS, BIO4, and STN were the most important influencing factors, explaining the variation of 15.37%, 12.77%, and 11.74%, respectively (Fig. 7b). The R2 for the 11 most important variables was 0.98.

Pearson correlation analysis revealed the relationship between yield, active components, soil physical properties, soil chemical properties, soil biological properties, and climatic factors using the 11 most important variables (Fig. 8). The results confirmed that yield was significantly and positively correlated with ARA, BIO4, BIO7 (P < 0.001), and STK (P < 0.05), but negatively correlated with ALT (P < 0.001) and ST (P < 0.05). GAS content was significantly and positively correlated with SAN, STN (P < 0.001), ALT (P < 0.01), and MRA (P < 0.05), but negatively correlated (P < 0.05) with ARA, BIO4, BIO7 (P < 0.001), and SAK (P < 0.01). In addition, ARA was significantly and positively correlated with BIO4 and BIO7 (P < 0.001), but negatively correlated with ALT (P < 0.001). For MRA, it was significantly and positively correlated with FSI (P < 0.05).

The constructed PLS-PM models can explain 98% and 92% of the variability in yield and GAS content, respectively (Fig. 9a and b). Regarding the PLS-PM model of the yield of G. elata Bl., (Fig. 9(a), plant subspecies and soil biological properties had a direct positive effect, with the path coefficients of 0.62 (P < 0.01) and 0.64 (P < 0.01), respectively. Soil physical properties had a direct positive effect on soil chemical properties, with a path coefficient of 0.68 (P < 0.001). Meanwhile, soil chemical properties had a direct positive impact on soil biological properties, with a path coefficient of 0.47 (P < 0.05). The goodness-of-fit of the yield of G. elata Bl. was 0.70. Regarding the PLS-PM model of the GAS content of G. elata Bl. (Fig. 9b), it revealed plant subspecies and soil chemical properties had a direct positive effect, with the path coefficients of 0.95 (P < 0.001) and 0.56 (P < 0.01), respectively. In addition, soil physical properties had a direct positive effect on soil chemical properties, with a path coefficient of 0.71 (P < 0.001). The goodness-of-fit of the GAS content of G. elata Bl. was 0.72.

Indirect effects and total effects were shown in Fig. 9(c) and (d). Soil physical properties had an indirect effect (0.32) on soil biological properties, leading to a total effect of 0.48. Soil physical properties had also an indirect effect (0.33) on the yield of G. elata Bl., leading to a total effect of 0.39. Moreover, soil chemical properties had an indirect effect (0.30) on the yield of G. elata Bl., leading to a total effect of 0.33. For the PLS-PM model of the GAS content of G. elata Bl., soil physical properties had an indirect effect (−0.11) on soil biological properties, leading to a total effect of −0.48. Soil physical properties had also an indirect effect (0.26) on the GAS content of G. elata Bl., leading to a total effect of 0.15. Soil chemical properties had an indirect effect (−0.04) on the GAS content of G. elata Bl., leading to a total effect of 0.52.

Quantitatively evaluate the effects of plant subspecies, soil properties and climatic factors on the yield and gastrodin content of cultivated G. elata Bl. based on hierarchical partitioning. (a) Yield; (b) Gastrodin content. ARA represents Armillaria relative abundance; MRA represents Mycena relative abundance; FSI represents fungal Shannon index; BSI represents bacterial Shannon index; BCI represents bacterial Chao1 index; FCI represents fungal Chao1 index; SMC represents soil moisture content; SOM represents soil organic matter; STN rep-resents soil total nitrogen; STP represents soil total phosphorus; STK represents soil total potassium; SAN represents soil available nitrogen; SAP represents soil available phosphorus; SAK represents soil available potassium; ALT represents altitude; BIO1–BIO19 represent temperature and precipitation data from the WorldClim database; PS represents plant subspecies; ST represents soil texture.

Pearson correlation analysis among yield, gastrodin content, soil properties and climatic factors. (a) Yield; (b) Gastrodin content. GAS represents gastrodin; ARA represents Armillaria relative abundance; MRA represents Mycena relative abundance; FSI represents fungal Shannon index; FCI represents fungal Chao1 index; STN represents soil total nitrogen; STP represents soil total phosphorus; STK represents soil total potassium; SAN represents soil available nitrogen; SAK represents soil available potassium; ALT represents altitude; BIO1–BIO19 represent temperature and precipitation data from the WorldClim database; ST represents soil texture. * represents P < 0.05, ** represents P < 0.01, and *** represents P < 0.001.

The interaction relationship among yield, gastrodin content, plant subspecies, soil properties and climatic factors based on the PLS-PM model. (a) Direct effects of latent variables and manifest variables on yield; (b) Direct effects of latent variables and manifest variables on gastrodin content; (c) Indirect effects and total effects on yield; (d) Indirect effects and total effects on gastrodin content; The circles represent latent variables, and the rectangles represent manifest variables; The arrows represent the link between them, and the numbers next to the arrows indicate path coefficients; The solid red lines indicate negative effects, and the solid blue lines indicate positive effects; GAS represents gastrodin; PS represents plant subspecies; CF represents climatic factors; SPP represents soil physical properties; SCP represents soil chemical properties; SBP represents soil biological properties; Goodness of Fit statistics are shown in the frames; * represents P < 0.05, ** represents P < 0.01, and *** represents P < 0.001.

Discussion

The establishment conditions and quantitative process for the models

Previous studies have mostly explored the influence of soil properties or climate factors on the yield and quality of G. elata Bl., ignoring the effects of different plants50,51. However, the effect of plant subspecies is usually greater than other factors52. Additionally, the authentication of G. elata Bl. was mainly based on its phenotypic characteristics or personal experience in the past53, while DNA barcoding has become an extremely widely used technology in molecular marker-based species authentication technologies, given its standardization, minimization, and scalability54. In particular, ITS2 could be identified at the subspecies taxonomic unit and had the fastest growth in the number of major plant DNA barcoding sequences in the Genbank database55. However, until now, the identification and taxonomy of G. elata Bl. subspecies in only two provinces (Yunnan and Hubei) have been performed by SSR markers, SNP markers, and SLAF sequencing56,57. Our results showed that G. elata Bl. from seven provinces in China’s core producing regions was categorized into G. elata Bl. f. elata (known as hongtianma in Chinese) and G. elata Bl. f. glauca (known as wutianma in Chinese) based on ITS2. Moreover, G. elata Bl. subspecies also showed its geographical distribution characteristics. Specifically, G. elata Bl. from Yunnan, Guizhou and Sichuan were one type, while those from Hubei, Shaanxi and Gansu were another type.

Quantifying the influences of plant subspecies, soil properties, and climate factors on the yield and quality of G. elata Bl. is a premise for determining key influencing factors and optimizing cultivation strategies. The application of HP and PLS-PM achieved a quantitative evaluation process for the influences of these influencing factors on the yield and quality of G. elata Bl. Past studies have reported that the yield and quality of G. elata Bl. were significantly correlated with soil properties and climatic factors21,51, but few studies quantitatively evaluated the influence because the multicollinearity caused by strong correlations among soil properties or climatic factors usually resulted in the errors of evaluation. Fortunately, the emergence of HP successfully solved the problem, which has become an important statistical method to analyze the independent effects of the predictor variables on the response variable45,46. Although HP could identify the most important soil properties and climatic factors affecting the yield and quality of G. elata Bl., it ignored the direct and indirect effects between different types of environmental factors. Comparing with HP, the structural equation model could directly quantify the causalities between multiple variables58. Especially, PLS-PM, which has lower requirements for samples and is more suitable for comprehensive analysis of a newly constructed structure47. Based on the preliminary results of HP, the PLS-PM was successfully conducted to analyze the interaction patterns between plant subspecies, key soil properties and climatic factors, and quantify their comprehensive influences on the yield and quality of G. elata Bl. in this study. To our knowledge, there is currently no research focusing on the effects of genetic and multiple environmental factors on the yield and quality of G. elata Bl. Therefore, the novelty of this study lies in the discovery of the relative importance and mechanism of these influencing factors for the first time.

The differences in the effects of Armillaria and Mycena on the yield and quality of G. elata Bl.

G. elata Bl. is one of the heterotrophic plants without chlorophyll, whose growth and development require symbiosis with Armillaria and Mycena10,11,12,13. Armillaria play important roles in the nutrient supply and growth modulation of G. elata Bl., and they will undergo severe competition with native soil organisms before colonization and become symbiotic with G. elata Bl.59. For Mycena, because seeds of G. elata Bl. have no endosperm, their sexual reproduction depends on the nutrients provided by the embryo cells infected by Mycenato complete seed germination60,61. Our results showed that Armillaria could be detected in all soil environments at harvest, while Mycena could only be detected in four soil environments. This result was consistent with their role in the growth and development of G. elata Bl.59,60,61. Namely, the main role of Mycena was to promote the germination of G. elata Bl. seeds in the early stage, while the main role of Armillaria was to promote the growth of G. elata Bl. tubers in the later stage.

Based on the result of HP, the ARA was the most important factor in soil biological properties, which explained a variation of 74.14% for the yield of G. elata Bl., which was approximately three times the sum of all other soil biological factors. Meanwhile, ARA was also extremely correlated with the yield of G. elata Bl., whose correlation coefficient was 0.98 (P < 0.001), and ARA had a direct positive effect on yield with the path coefficients of 0.64 (P < 0.01). Compared with the effect of Armillaria on yield, its independent effect and correlation on GAS content were lower. Even ARA and GAS showed a negative correlation (P < 0.001), because the higher the yield of G. elata Bl., the lower the GAS content. Based on this, it can be inferred that the main role of Armillaria was to increase the yield of G. elata Bl. rather than quality, which is the same as previous studies14. Interestingly, our study also found that the soil environment of high-quality G. elata Bl. contained more Mycena. HP analysis also exhibited that MRA was the second most important variable (explained variation of 34.45%), and correlation analysis exhibited that MRA and GAS content had a significant correlation (P < 0.05). Although Mycena cannot directly improve the GAS content of G. elata Bl., they may promote GAS synthesis by enhancing other beneficial microorganisms or soil nutrients51,59,62. These results demonstrated the importance and difference of soil microorganisms on the yield and quality formation of G. elata Bl., especially excellent Armillaria and Mycena should be selected in the cultivation of G. elata Bl..

The mechanism affecting G. elata Bl. yield and quality and the direction of optimizing cultivation strategies

The mechanism of influencing factors to the yield of G. elata Bl. could be summarized as two aspects: direct effect and indirect effect. On the one hand, plant subspecies as the main factor directly determined the yield of G. elata Bl. from the genetic. On the other hand, soil physical properties affected chemical properties, which in turn affected biological properties and ultimately yields. Among them, the ARA was the most important soil biological factor, while STP and STK were the most important soil chemical factors for the yield of G. elata Bl.. Similarly, the mechanism of influencing factors to the quality of G. elata Bl. could also be summarized as two aspects. To sum up, the specific regulation direction for improving the yield and quality of G. elata Bl. should include as follows: (1) introduce superior varieties for cultivation, which is the dominant factor that determines the yield and quality; (2) select the soil texture with higher clay content, such as loam or clay loam; (3) pay attention to the improvement of soil organic matter, because it is closely related to soil N, P, and K, and the cultivation of G. elata Bl. cannot use any fertilizer; (4) cultivate excellent Armillaria and Mycena strains, which play an important role in the seeds germination and growth of G. elata Bl.; (5) cultivate G. elata Bl. in suitable ecological areas based on GMPGIS, which can ensure that the climate is fit for their growth.

In general, the factors affecting the yield and quality of G. elata Bl. include plant subspecies, soil properties, environmental factors, processing methods, and tree species inoculated with Armillaria63,64,65. However, it is difficult to quantify all factors because of the differences in processing methods and tree species inoculated with Armillaria. In this study, the models were conducted using plant subspecies, soil properties, environmental factors, yield and quality, and selected the most important influencing factors. Despite these advancements, the study has certain limitations. While HP and PLS-PM effectively partitioned variance and modeled pathways, these approaches assume linear relationships and may not fully capture non-linear interactions, such as threshold effects of temperature on microbial activity or synergistic effects between soil nutrients and microbial communities66,67. In addition, the regional specificity of the study, for example, the soil in this study has only three types of loamy sand, loam, and clay loam, which limits the direct application of these findings to regions with contrasting edaphic conditions. Future research should employ hybrid modeling approaches, such as integrating PLS-PM with machine learning techniques, to better reconcile these complexities and enhance the predictive accuracy of multifactorial agricultural models. Furthermore, expanding the study to include non-Chinese cultivars and diverse ecological regions would improve the generalizability of the findings and provide a more comprehensive understanding of G. elata Bl. cultivation dynamics worldwide.

Conclusion

This study clarified the mechanism of plant subspecies, soil properties, and climatic factors on the yield and quality of cultivated G. elata Bl. The results proved that Armillaria relative abundance, soil available potassium, and temperature seasonality were the most soil biological properties, soil chemical properties, and climate factors, respectively. Furthermore, plant subspecies as the main factor directly determined the yield and quality of G. elata Bl. from the genetic material. Soil physical properties affected chemical properties, which in turn affected biological properties and ultimately yields. Meanwhile, soil physical properties affected quality by influencing soil chemical properties. Overall, prioritizing superior varieties, selecting the clay soil rich in organic matter and symbiotic microorganisms, and planting them in suitable ecological areas may be the key to boosting the yield and quality of G. elata Bl..

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- ALT:

-

altitude

- ANOVA:

-

one-way analysis of variance

- ARA:

-

Armillaria relative abundance

- ASVs:

-

amplicon sequence variants

- BCI:

-

bacterial Chao1 index

- BSI:

-

bacterial Shannon index

- CF:

-

climatic factors

- FCI:

-

fungal Chao1 index

- FSI:

-

fungal Shannon index

- G. elata Bl.:

-

Gastrodia elata Blume

- GAS:

-

gastrodin

- GMPGIS:

-

Global Medicinal Plant Geographic Information System

- HBA:

-

p–hydroxybenzyl alcohol

- HP:

-

hierarchical partitioning

- HPLC:

-

high performance liquid chromatography

- MRA:

-

Mycena relative abundance

- PLS-PM:

-

partial least squares path modeling

- PS:

-

plant subspecies

- SAK:

-

soil available potassium

- SAN:

-

soil available nitrogen

- SAP:

-

soil available phosphorus

- SBP:

-

soil biological properties

- SCP:

-

soil chemical properties

- SMC:

-

soil moisture content

- SOM:

-

soil organic matter

- SPP:

-

soil physical properties

- ST:

-

soil texture

- STK:

-

soil total potassium

- STN:

-

soil total nitrogen

- STP:

-

soil total phosphorus

References

Gong, M. Q. et al. Traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, applications, and quality control of Gastrodia Elata Blume: A comprehensive review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 319, 22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2023.117128 (2024).

Zhan, H. D. et al. The rhizome of Gastrodia Elata Blume - An ethnopharmacological review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 189, 361–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2016.06.057 (2016).

Ye, P. et al. A small molecule 20 C from Gastrodia elata inhibits α-synuclein aggregation and prevents progression of Parkinson’s disease. Cell. Death Dis. 14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-023-06116-0 (2023).

Chao-Qi, Z. et al. Sleep promoting and omics exploration on probiotics fermented Gastrodia Elata Blume. Npj Sci. Food. 8 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-024-00277-8 (2024).

Huang, Y. J. et al. Gastrodia Elata Blume water extract modulates neurotransmitters and alters the gut microbiota in a mild social defeat stress-induced depression mouse model. Phytother Res. 35, 5133–5142. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.7091 (2021).

Kim, N. H. et al. Antitumor and Immunomodulatory effect of Gastrodia Elata on colon cancer In vitro and In vivo. Am. J. Chin. Med. 45, 319–335. https://doi.org/10.1142/s0192415x17500203 (2017).

Liu, Y. & Huang, G. The chemical composition, Pharmacological effects, clinical applications and market analysis of Gastrodia Elata. Pharm. Chem. J. 51, 211–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11094-017-1584-5 (2017).

Yang, S. & Li, J. Effect of Gastrodia Elata Bl cultivation under forest stands on runoff, erosion, and nutrient loss. Forests 15 (7), 1127. https://doi.org/10.3390/f15071127 (2024).

Wang, X. et al. Decrease in beneficial bacteria and increase in harmful bacteria in Gastrodia seedlings and their surrounding soil are mainly responsible for degradation of Gastrodia asexual propagation. Front. Plant. Sci. 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2024.1334958 (2024).

Yuan, Y. et al. The Gastrodia Elata genome provides insights into plant adaptation to heterotrophy. Nat. Commun. 9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03423-5 (2018).

Xu, Y. et al. A chromosome-scale Gastrodia Elata genome and large-scale comparative genomic analysis indicate convergent evolution by gene loss in mycoheterotrophic and parasitic plants. Plant. J. 108, 1609–1623. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.15528 (2021).

Camprubi, A. et al. Plant performance and metabolomic profile of Loquat in response to mycorrhizal inoculation, armillaria mellea and their interaction. Agronomy-Basel 10 https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10060899 (2020).

Yu, E. et al. An exploration of mechanism of high quality and yield of Gastrodia Elata Bl. F. glauca by the isolation, identification, and evaluation of Mycena. Front. Microbiol. 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1220670 (2023).

Yu, E. et al. An exploration of mechanism of high quality and yield of Gastrodia Elata Bl. F. glauca by the isolation, identification and evaluation of Armillaria. BMC Plant. Biol. 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-022-04007-8 (2022).

Chen, W. C. et al. Method development and validation for the high-performance liquid chromatography assay of Gastrodin in water extracts from different sources of Gastrodia Elata Blume. J. Food Drug Anal. 23, 803–810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfda.2015.02.006 (2015).

Ji, N., Liu, P., Zhang, N., Yang, S. & Zhang, M. Comparison on bioactivities and characteristics of polysaccharides from four varieties of Gastrodia Elata Blume. Front. Chem. 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2022.956724 (2022).

Tao, J. et al. Relationships among genetic makeup, active ingredient content, and place of origin of the medicinal plant Gastrodia tuber. Biochem. Genet. 47, 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10528-008-9201-7 (2009).

Yang, Y. et al. Biochar stability and impact on soil organic carbon mineralization depend on Biochar processing, aging and soil clay content. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 169 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2022.108657 (2022).

Philippot, L., Chenu, C., Kappler, A., Rillig, M. C. & Fierer, N. The interplay between microbial communities and soil properties. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 22, 226–239. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-023-00980-5 (2024).

Wang, C. H. et al. Effects of Armillaria species on growth and quantity of active medicinal components of G. elata Bl. F. elata tubers along an altitude gradient: evidence F.om empirical experiments. Phytochem Lett. 54, 101–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytol.2023.01.016 (2023).

Kim, C., Kim, D., Kim, H., Song, Y. & Lee, W. Production of immature rhizomes by breaking dormancy under low temperature of Gastrodia Elata Blume. Planta Med. 82. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0036-1596606 (2016).

Godo, T., Hashimoto, T., Nakata, M. & Miyoshi, K. The effects of illumination, temperature and 6-benzylaminoprine on asymbiotic seed germination and protocorm development in vitro in the achlorophyllous Orchid Gastrodia pubilabiata Sawa. Vitro Cell. Dev-Pl. 56, 230–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11627-020-10061-4 (2020).

Li, Y., Kong, D., Fu, Y., Sussman, M. R. & Wu, H. The effect of developmental and environmental factors on secondary metabolites in medicinal plants. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 148, 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.01.006 (2020).

Chen, L. et al. Dynamics of fungal communities during Gastrodia Elata growth. BMC Microbiol. 19 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-019-1501-z (2019).

Chinese Pharmacopoeia Committee. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China59–60 (China Medical Science and Technology, 2020).

White, T. J. Amplification and Direct Sequencing of Fungal Ribosomal RNA Genes for Phylogenetics. PCR Protocols: A Guide To Methods and Applications315–322 (Academic, 1990).

Gao, T. et al. Evaluating the feasibility of using candidate DNA barcodes in discriminating species of the large Asteraceae family. BMC Evol. Biol. 10 https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-10-324 (2010).

Kress, W. J., Wurdack, K. J., Zimmer, E. A., Weigt, L. A. & Janzen, D. H. Use of DNA barcodes to identify flowering plants. P Nati Acad. Sci. USA. 102, 8369–8374. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0503123102 (2005).

Hollingsworth, P. M. et al. A DNA barcode for land plants. P Nati Acad. Sci. USA. 106, 12794–12797. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0905845106 (2009).

Sang, T., Crawford, D., Stuessy, T. & Chloroplast, D. N. A. phylogeny, reticulate evolution, and biogeography of Paeonia (Paeoniaceae). Am. J. Bot. 84, 1120–1120. https://doi.org/10.2307/2446155 (1997).

Taberlet, P., Gielly, L., Pautou, G. & Bouvet, J. Universal primers for amplification of three non-coding regions of Chloroplast DNA. Plant. Mol. Biol. 17, 1105–1109. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00037152 (1991).

Mor, B., Garhwal, S. & Kumar, A. A systematic review of hidden Markov models and their applications. Arch. Comput. Methods E. 28, 1429–1448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-020-09422-4 (2021).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G. & Tamura, K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw054 (2016).

Yang, X. et al. Determination of soil texture by laser diffraction method. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 79, 1556–1566. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2015.04.0164 (2015).

Kyebogola, S. et al. Comparing Uganda’s Indigenous soil classification system with world reference base and USDA soil taxonomy to predict soil productivity. Geoderma Reg. 22, e00296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geodrs.2020.e00296 (2020).

Su, J. et al. Soil conditions and the plant microbiome boost the accumulation of monoterpenes in the fruit of Citrus reticulata ‘Chachi’. Microbiome 11 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-023-01504-2 (2023).

Muscarella, S. M. et al. Water reuse of treated domestic wastewater in agriculture: effects on tomato plants, soil nutrient availability and microbial community structure. Sci. Total Environ. 928, 172259–172259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.172259 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. NRT1.1B improves selenium concentrations in rice grains by facilitating selenomethinone translocation. Plant. Biotechnol. J. 17, 1058–1068. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.13037 (2019).

Bolyen, E. et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible Microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 852–857. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9 (2019).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods. 13, 581–. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3869 (2016).

Wu, J. et al. A new GIS model for ecologically suitable distributions of medicinal plants. Chin. Med-UK. 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13020-019-0226-0 (2019).

Fick, S. E. & Hijmans, R. J. WorldClim 2: new 1-km Spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 4302–4315. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5086 (2017).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. (2013).

Wei, T. et al. Package ‘corrplot’. Statistician 56 (316), e24 (2017).

Lai, J., Zou, Y., Zhang, S., Zhang, X. & Mao, L. glmm.hp: an R package for computing individual effect of predictors in generalized linear mixed models. J. Plant. Ecol. 15, 1302–1307. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpe/rtac096 (2022).

Lai, J., Zhu, W., Cui, D., Mao, L. & Liao, J. Extension of the Glmm.hp package to zero-inflated generalized linear mixed models and multiple regression. J. Plant. Ecol. 16. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpe/rtad038 (2023).

Henseler, J. Advanced Methods for Modeling Markets361 (Springer International Publishing, 2017).

Tang, S. et al. Microbial community succession in soil is mainly driven by carbon and nitrogen contents rather than phosphorus and sulphur contents. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 180 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2023.109019 (2023).

Wickham, H. ggplot2. Wires Comput. Stat. 3 (2), 180–185. https://doi.org/10.1002/wics.147 (2011).

Xie, X. et al. Changes in soil chemistry and microbial communities in rhizospheres of planted Gastrodia Elata on a barren slope and under a forest. Forests 15 https://doi.org/10.3390/f15020331 (2024).

Xinyu, Y. et al. Discovery of seed germinating F.ngi (Mycetinis scorodonius) F.om Gastrodia Elata Bl. F. glauca S. chow in Changbai mountain and examination of their germination ability. Sci. Rep-UK. 14 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63189-3 (2024).

Luo, H. et al. Research progress on quality assurance of genuine Chinese medicinal in Sichuan. Chin. Med-UK. 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13020-021-00428-z (2021).

Yang, P. et al. Rapid authentication of variants of Gastrodia Elata Blume using near-infrared spectroscopy combined with chemometric methods. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2023.115592 (2023).

Ren, F. M. et al. DNA barcoding of Corydalis, the most taxonomically complicated genus of Papaveraceae. Ecol. Evol. 9, 1934–1945. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.4886 (2019).

Zhu, S., Liu, Q., Qiu, S., Dai, J. & Gao, X. DNA barcoding: an efficient technology to authenticate plant species of traditional Chinese medicine and recent advances. Chin. Med-UK. 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13020-022-00655-y (2022).

Wang, Y., Shahid, M. Q., Ghouri, F., Ercisli, S. & Baloch, F. S. Development of EST-based SSR and SNP markers in Gastrodia Elata (herbal medicine) by sequencing, de Novo assembly and annotation of the transcriptome. 3 Biotech. 9 https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-019-1823-4 (2019).

Xu, Z. et al. Genome-wide assessment of genetic variation and differentiation for Gastrodia Elata germplasm based on SLAF sequencing. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 70, 1971–1984. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-023-01548-1 (2023).

Fan, Y. et al. Applications of structural equation modeling (SEM) in ecological studies: an updated review. Ecol. Process. 5, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-016-0063-3 (2016).

Wang, Y. et al. Effect of symbiotic fungi-Armillaria gallica on the yield of Gastrodia Elata Bl. and insight into the response of soil microbial community. Front. Microbiol. 14 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1233555 (2023).

Zeng, X. et al. Transcriptomic analyses reveal clathrin-mediated endocytosis involved in symbiotic seed germination of Gastrodia Elata. Bot. Stud. 58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40529-017-0185-7 (2017).

Li, Y. Y., Guo, S. X. & Lee, Y. I. Ultrastructural changes during the symbiotic seed germination of Gastrodia Elata with fungi, with emphasis on the fungal colonization region. Bot. Stud. 61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40529-019-0280-z (2020).

Barazetti, A. R. et al. Formulations of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi inoculum applied to soybean and corn plants under controlled and field conditions. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 142, 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2019.05.015 (2019).

Subramaniam, S., Wen, X. Y. & Jing, P. One-step microwave curing-dehydration of Gastrodia Elata Blume: relationship between phytochemicals, water States and morphometric characteristics. Ind. Crop Prod. 153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.112579 (2020).

Park, E. J. & Lee, W. Y. Quantitative effects of various tree species on tuber growth and Pharmacological compositions of Gastrodia Elata. Hortic. Environ. Biote. 54, 357–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13580-013-0030-1 (2013).

Xie, Y. K. et al. Effects of steam and water blanching on drying characteristics, water distribution, microstructure, and bioactive components of Gastrodia elata. Plants-Basel 12. (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12061372

He, X. et al. Temperature and microbial metabolic limitations govern microbial carbon use efficiency in the Tibetan alpine grassland. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 206, 105880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2025.105880 (2025).

Zou, Q. et al. The synergistic interaction effect between Biochar and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria on beneficial microbial communities in soil. Front. Plant. Sci. 15, 1501400. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2024.1501400 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Science and Technology Achievement Transfer and Transformation Guidance Project (2022ZHXC0101) and the Key Discipline Construction Project of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2020ZD07).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.J.J.: data curation, writing-original draft preparation. H.J., D.Z.: writing-reviewing and editing. J.D., Y.H.: conceptualization and methodology. Y.Y., Q.L.: software, validation. H.J.: supervision. M.M.H.: investigation.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, X., Dai, J., Huang, Y. et al. Comprehensive quantitative evaluation and mechanism analysis of influencing factors on yield and quality of cultivated Gastrodia elata Blume. Sci Rep 15, 18457 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99706-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99706-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Quality evaluation of Capitatae Fructus from different geographical regions in China

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Quality comparison of Gastrodia elata grown using artificial mushroom cultivation kits and traditional wood-based cultivation

Scientific Reports (2025)