Abstract

Given the high predicted probability of future pandemics, it is essentially important that we understand the benefits and drawbacks of online learning compared to traditional in-class learning—especially in specialized education like healthcare-related educational settings. This is the first study to investigate the first-person perception of online learning, knowledge assessment, and longitudinal confidence in clinical skills among third-year ophthalmology residents studying during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic in Thailand. This survey-based study enrolled all 74 ophthalmologists that graduated in 2020 from Thailand’s eleven accredited ophthalmology training centers. The results of this study revealed general acceptance and approval of online learning in a pandemic setting that prevented traditional in-class learning. Respondents overwhelmingly endorsed online knowledge examination/assessment and their trust in an honor system among online examinees; however, they at the same time strongly stressed the need for controls to improve the prevention of cheating during online testing. Regarding study ophthalmologist confidence in performing ophthalmologic procedures and surgeries compared between immediately after graduation from ophthalmology training and at one year after graduation, the results indicate that, despite the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, most study ophthalmologists had and maintained a relatively high level of confidence in performing various ophthalmic procedures and surgeries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to the global spread of the coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19 virus) in 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared that the disease had developed into a global pandemic. This resulted in various measures being implemented globally, including area lockdowns and social distancing, to prevent or reduce the spread of the disease. Thailand implemented these same measures and many resulting effects were observed, including the education and training of medical students. Specific areas of medical education that were impacted included lectures, case discussions, patient history taking, physical examinations, procedures, and surgeries. Given the relative importance of medical education and training, the impact of the pandemic, including the necessity to replace in-class training with online training, has become an important area of post-pandemic study to comparatively assess the effects of online training on medical knowledge and skills.

A study investigated the attitude of 2,721 medical students towards online learning during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom1. Using a cross-sectional approach and a questionnaire, that study found increased online learning during the pandemic compared to before the pandemic [7–10 h versus (vs.) 4–6 h per week, respectively; p < 0.005]. Their results also showed the greatest perceived benefits of online learning to be flexibility and time savings, whereas the most commonly reported challenges were internet connectivity issues and family/home disruptions. A similar study was conducted among 652 medical students in Jordan using a questionnaire2. That group found that only 26.8% of medical students were satisfied with remote learning. The most significant reported drawback was the lack of interaction with instructors and classmates, and the most prevalent limitation/challenge was internet connectivity issues, which affected 69.1% of respondents. Moreover, the majority of medical students (75.5%) in that study reported believing a blended learning approach—combining online and traditional learning—to be the most effective learning method. Concerning online assessment, a study was conducted to assess the first-person perspectives of 100 Indian medical students specific to uninvigilated online formative assessment tests conducted in 20203. This was a cross-sectional study that also used a questionnaire. The findings revealed that most medical students (73.2%, p < 0.001) perceived online examinations to be an effective and beneficial method of knowledge assessment. Internet connectivity issues were identified as the most concerning challenge (85.5%, p < 0.001). Moreover and importantly, a significant number of students (43.3%, p < 0.05) in that study reported cheating to be easier to engage in during online testing, and many suggested the need for enhanced monitoring during the online examination process.

Given the differences between and among different types of medical training for different medical specialties, it is important to singularly evaluate the effectiveness of online learning compared to traditional in-class learning for each medical specialty, including ophthalmology. The aim of this study was to investigate the first-person perception of online learning, knowledge assessment, and longitudinal confidence in clinical skills among third-year ophthalmology residents in Thailand during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, as no previous studies have addressed this topic. The results of this study will improve our understanding of the benefits and drawbacks of online learning compared to traditional in-class learning, and this improved understanding will help to guide improvement in online ophthalmologic training protocols for use in similar future events. Moreover, these findings and improvements in understanding may also be generalizable to other online medical training contexts.

Results

Survey response rate and respondent demographics

Seventy-four physicians graduated from ophthalmology training in Thailand in 2020, and all 74 ophthalmologists agreed to participate in this study by returning a completed questionnaire. As such, the survey response rate was 100%. Concerning gender distribution, 49 of 74 (66.2%) respondents identified as female.

Online learning compared between before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

Prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the vast majority of ophthalmology residents enrolled in this study reported spending less than one hour per day learning online. However and not surprisingly—during the pandemic, the vast majority of residents reported spending 1–3 h per day learning online (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1).

Questionnaire response results

Responses to survey questions were communicated using a 1-to-5-point Likert scale in which scores of 4 or 5 denote agreement or strong agreement, respectively; scores of 1 or 2 denote disagreement or strong disagreement, respectively; and, a score of 3 reflects neutral impartiality. In this study, ‘agree’ and ‘strongly agree’, and ‘disagree’ and ‘strongly disagree’ were pooled for the data analysis. Responses to general survey questions and the advantages and disadvantages of online learning compared among those who disagreed, were neutral, or agreed are shown in Table 1 and Likert-scale distribution of responses were shown in Fig. 2. The questionnaire included questions that were categorized into the 3 following groups: experience with, advantages of, and disadvantages of online learning. The participants reported online learning to be enjoyable (44.6%) or neutral (35.1%), and that it helps to motivate the learner to want to learn (40.5%) or were neutral (41.9%). Concerning the potential for improvement in the online learning experience, the majority of respondents expressed a desire for increased interactivity (67.6%) among students and between students and the teacher. Interestingly, only 27.0% of respondents reported feeling that online learning is just as effective as in-class instruction. However, about one-quarter (24.3%) of our study cohort indicated a preference for online learning over learning in a traditional classroom setting.

Reported advantages of learning online

The main advantages of online learning were reduced travel time (90.5%), having the opportunity to study in a private environment (90.5%), increased flexibility (85.1%), and the opportunity to learn at various different locations (79.7%) (Table 1).

Reported disadvantages of learning online

Our survey respondents also communicated some perceived disadvantages of online learning. Disadvantages reported by large proportions of respondents included a lack of interaction with peers (75.7%), decreased motivation to learn (45.9%), difficulty in maintaining focus (47.3%), and internet connectivity issues (45.9%). Notably, the vast majority of ophthalmology residents (86.5%) reported believing that online learning could not fully displace the educational experience gained from traditional classroom learning (Table 1).

Respondent perception of online knowledge examination/assessment

Responses to online knowledge examination/assessment survey questions compared among those who disagreed, were neutral, or agreed are shown in Table 2 and Likert-scale distribution of responses are shown in Fig. 3. Importantly, the vast majority of respondents (83.8%) reported believing online examinations to be as effective as traditional in-class examinations for assessing knowledge. Also of note, an overwhelming proportion of respondents (82.4%) communicated a belief that students taking an online exam could be trusted not to cheat similar to the level students would be expected not to cheat in an in-class examination setting. Regarding concerns—interestingly, a sizeable majority of respondents (82.4%) highlighted the need to implement measures to prevent cheating during online exams. Another major concern was internet connectivity issues (63.5%).

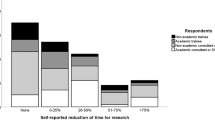

Reported confidence in performing ophthalmic procedures and surgeries

Study ophthalmologist confidence in performing ophthalmologic procedures and surgeries compared between immediately after graduation from ophthalmology training and at one year after graduation from ophthalmology training is shown in Table 3 and Likert-scale distribution of responses are shown in Fig. 4. The results of the self-assessment of respondent confidence levels were compared to the Entrustable Professional Skill Activity (EPA) and Direct Observe Procedure Skill (DOP) criteria outlined in the Ophthalmology Residency Training Program Curriculum of the Royal College of Ophthalmologists of Thailand (2017). The results indicate that, despite the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, most study ophthalmologists had and maintained a relatively high level of confidence in performing various ophthalmic surgeries, including pterygium excision, extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE) with intraocular lens (IOL) implantation, and phacoemulsification. They also reported having confidence in performing ophthalmic procedures, such as bright (B) scan ultrasonography, laser capsulotomy, laser iridotomy, and retinal laser photocoagulation. Respondents reported having lower levels of confidence in certain surgeries, such as external dacryocystorhinostomy, trabeculectomy, and muscle surgeries. Of note—from the follow-up survey conducted at one-year after graduation from ophthalmic training, the reported confidence in performing phacoemulsification surgeries significantly increased, while the reported confidence in performing external dacryocystorhinostomy surgeries significantly decreased.

Discussion

This is the first study to investigate the first-person perception of online learning, knowledge assessment, and longitudinal confidence in clinical skills among third-year ophthalmology residents studying during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic in Thailand. Our results demonstrate a statistically significant increase in the adoption of online learning among third-year ophthalmology residents in Thailand during 2020, primarily due to the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated restrictions. A study that surveyed medical students from 12 countries reported an increase from 13 to 79% in the number of schools that offered online learning before the pandemic to during the pandemic, respectively4. Furthermore, most students in that study expressed a desire for increased online learning opportunities in the future, suggesting a shift in perception to online education being viewed as a valuable mode of learning.

Our research found that most participants believe that online learning cannot replace classroom learning, with only 27% of respondents holding the view that online learning is as effective as classroom learning. This lukewarm perception of online learning may be attributed to the fact that this is the first group of ophthalmologists in Thailand to be taught via online learning. Another possible explanation may be that online education resources may not have been optimal since these resources had to be hastily developed and implemented. Strategies recommended by a previous study to help educational institutions better prepare for online learning included ensuring smooth website operations, monitoring server statistics, and encouraging the use of reliable tools like Zoom and Skype to optimize network usage5.

The main benefits of online learning found in our study and supported by previous studies include timesaving, the ability to learn in private spaces, flexibility, and accessibility from anywhere that has internet connectivity6. These advantages can help to guide future curriculum adjustments towards a more blended approach, combining online and in-class learning.

Similar to previous study, our study found the main disadvantages of online learning to be the lack of interaction among students and between students and the instructors, lack of concentration, and lack of motivation to learn during online class sessions7. Most of these factors may be explained by the fact that most online learning is conducted in a lecture format, which may result in less discussion, fewer questions, and lower engagement compared to traditional classroom learning. Another study investigated the use of Augmented Reality (AR) in medical student education8. AR creates a simulated real environment learning experience via the use of a headset and specialized applications. That study found that online learning using AR can help improve the understanding of learning material, the development of practical skills, and the development of communication skills.

In addition to the shift toward online learning, the COVID-19 pandemic similarly necessitated the transition to online knowledge examination/assessment. The majority of respondents in our study reported believing that online assessments are effective for evaluating knowledge similar to traditional in-class exams and that they are reliable. These findings align with those from a previous study conducted in Indian medical students3. Also similar to previous study9, we found the main concern among respondents to be internet connectivity issues.

This observed positive perception of online assessments may be due to the fact that online certification exams are typically multiple-choice question (MCQ) exams, and they do not include practical examinations or Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCEs). However, practical examinations are crucial in medical education, especially for specialist doctors who perform surgeries, including ophthalmologists. A cross-sectional study that investigated the utility of online OSCEs for medical students found positive results relative to validity, reliability, acceptability, educational impact, cost, and feasibility10. Additionally, previous study in online surgical OSCE stations found that 65% and 68% of participants considered online teaching more efficient and accessible, respectively, than in-class teaching11. The authors believe that developing online assessment systems for both MCQ exams and OSCEs will greatly benefit future education.

Although online learning and assessment were generally acceptable for delivering theoretical content, ophthalmology training poses distinct challenges because of its dependence on hands-on clinical examination and microsurgical skills. Essential competencies—including slit-lamp examination, fundoscopy, laser procedures, and intraocular surgery—require repeated practice, refined motor coordination, and real-time expert feedback, which cannot be adequately achieved through didactic online instruction alone. A systematic review of simulation-based training in ophthalmology showed extensive use of virtual reality, wet-lab, dry-lab, and e-learning approaches, with the Eyesi Surgical simulator demonstrating the strongest validity evidence and most consistent effectiveness, particularly for cataract surgery12. While simulation-based training can enhance technical performance in simulated settings and, in selected contexts, improve operating room outcomes, especially among junior trainees, the evidence remains heterogeneous, and simulation cannot replace supervised live surgical experience. Overall, these data support online and simulation-based learning as preparatory and adjunctive strategies rather than substitutes for direct clinical and surgical training.

This study provides key insights for improving ophthalmology residency training in Thailand. The preference for blended learning suggests that online platforms should be used for lectures and theoretical content, while in-person sessions focus on clinical and surgical skills. To promote engagement in online learning, programs should incorporate case discussions both within and across institutions, encouraging interaction and broader clinical exposure. Strengthening not only infrastructure but also content design and delivery will enhance online education in normal times and ensure preparedness for future disruptions like another pandemic.

Artificial intelligence (AI)–based assessment approaches have been increasingly applied in medical education, including automated evaluation of written examinations, image-based diagnostic tasks, and video-recorded procedural performance in ophthalmology training13,14. These approaches may enhance the assessment of online learning by providing more objective, scalable, and standardized measures, thereby partially addressing limitations associated with self-reported competency, particularly in remote or hybrid training settings. Further research is required to evaluate the validity, reliability, and educational impact of integrating AI-assisted assessment alongside conventional evaluation.

Limitations

This study also has some mentionable limitations. First, this study focused exclusively on ophthalmology residents in their final year of training (2020), which coincided with the full force of the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, our findings may primarily reflect short-term consequences that may necessitate additional research to ascertain the long-term implications of online learning and assessment. Secondly, this study only examined the first-person perceptions of online lecture-based instruction, neglecting other critical areas, such as patient examinations and surgical procedures. Third, our study questionnaire did not include open-ended questions, nor was it designed to elicit suggestions from respondents. Therefore, the qualitative depth is limited, which can restrict the ability to identify unanticipated issues and deeper insight into residents’ preferences cannot be explained. Fourth, despite our best effort to ensure the anonymity of survey respondents and their responses, it is possible that some respondents could not be certain or convinced that this was actually the case. As a result, it is possible that some answers to some questions could have been submitted that did not fully and/or truly reflect the respondent’s opinion or experience. Despite the conveniences associated with electronic questionnaires and communication, the potential for sacrificed confidentiality remains a concern in a research setting. Additionally, the study relied on self-reported confidence in clinical and surgical skills, which may not accurately reflect actual competence, and the potential for response bias should be acknowledge. Another important limitation is the absence of a comparison group trained exclusively under traditional methods. The control group was not possible due to the abrupt and nationwide transition to online formats during the pandemic, which restricts the ability to draw causal interferences regarding the effects of online learning. To build upon these findings, future research should incorporate comparative cohorts, evaluate the long-term efficacy of online learning, incorporate validated performance assessment, and include ophthalmology residents from all years of training to better understand the true effectiveness and limitations of online education. Incorporating interviews, focus groups, or open-ended survey would also help address these gaps. Further studies should focus on developing and assessing online learning formats for physical examination and surgical skills, which are essential components of specialty medical training.

Conclusion

The results of this study revealed general acceptance and approval of online learning in a pandemic setting that prevented traditional in-class learning. Respondents overwhelmingly endorsed online knowledge examination/assessment and their trust in an honor system among online examinees; however, they at the same time strongly stressed the need for controls to improve the prevention of cheating during online testing. Regarding study ophthalmologist confidence in performing ophthalmologic procedures and surgeries compared between immediately after graduation from ophthalmology training and at one year after graduation, the results indicate that, despite the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, most study ophthalmologists had and maintained a relatively high level of confidence in performing various ophthalmic procedures and surgeries. Respondent feedback from this study should be used to improve current online education protocols so that improved online training is ready when needed in the future.

Methods

Study design, participants, and ethical approval

This mixed-methods study employed a descriptive cross-sectional approach using a questionnaire to explore first-person perceptions of online learning, online knowledge assessment, and performing eye procedures and surgeries in the context of online learning during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. This study also yields longitudinal data resulting from a comparison between respondent confidence performing eye procedures and surgeries between post-graduation and after one year of ophthalmology practice. Thailand has 11 medical institutions that provide accredited ophthalmology training, and all 11 of those centers are represented in our study cohort. The names of those 11 centers are listed in the authors’ affiliations section of the title page. A total of 74 physicians graduated from ophthalmology training in Thailand in 2020, and all 74 of those ophthalmologists were invited to formally join this study by completing and returning the study questionnaire. Of the 74 invitations to join the study, all 74 ophthalmologists returned a completed questionnaire for a 100% survey response rate. The protocol for this study was reviewed and approved by the Central Research Ethics Committee (CREC; Bangkok, Thailand) (COA-CREC067/2021). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Eligible study participants were informed that completion and submission of the questionnaire using an electronic signature indicated voluntary formal intent to join the study. Eligible study participants were also informed that all data collection procedures were designed to yield data that preserves the anonymity of the respondents, and that the collected data would only be used for research purposes. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Questionnaire design

The questionnaire used in this study was an online survey created using the Google Forms feature (Google; Alphabet, Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA). Answers to survey questions were communicated by the respondent using a 5-point Likert scale with a 1 reflecting strong disagreement, and a 5 reflecting strong agreement with the question. The main sections of the questionnaire were, as follows:

-

1.

General information of respondents:

-

Gender

-

Institution

-

Experience with online learning

-

-

2.

Perception of and satisfaction with online learning and online examinations:

-

This section comprises 24 questions and 12 questions for online learning and online examinations, respectively.

-

-

3.

Confidence in performing eye procedures and surgeries:

-

This section comprises 24 questions and 14 questions for eye procedures and eye surgeries, respectively.

-

Only this section of questionnaire was administered twice: once immediately after completing the academic program and then again after one year of professional experience. This strategy aimed to assess any changes in respondent confidence levels between immediately after training and after accumulating 1-year of post-training professional experience.

-

Statistical analysis

All data management tasks and statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical variables are presented as number and percentage, normally distributed continuous variables are expressed as mean plus/minus ( ±) standard deviation, and non-normally distributed continuous variables are given as median (minimum [min]-maximum [max]). Two separate statistical comparisons were conducted. First, a comparison in online learning use between before and during the COVID-19 pandemic; and second, a comparison in confidence scores between immediately after graduation from ophthalmology training and at one year after graduation from ophthalmology training where both performed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. A p-value less than 0.05 was regarded as being statistically significant for all tests.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Dost, S., Hossain, A., Shehab, M., Abdelwahed, A. & Al-Nusair, L. Perceptions of medical students towards online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national cross-sectional survey of 2721 UK medical students. BMJ Open 10(11), e042378 (2020).

Al-Balas, M. et al. Distance learning in clinical medical education amid COVID-19 pandemic in Jordan: current situation, challenges, and perspectives. BMC Med. Educ. 20, 341 (2020).

Snekalatha, S. et al. Medical students’ perception of the reliability, usefulness and feasibility of unproctored online formative assessment tests. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 45(1), 84–88 (2021).

Stoehr, F. et al. How COVID-19 kick-started online learning in medical education—The DigiMed study. PLoS ONE 16(9), e0257394 (2021).

Jiang, Z. et al. Twelve tips for teaching medical students online under COVID-19. Med. Educ.Online. 26(1), 1854066 (2021).

Mukhtar, K., Javed, K., Arooj, M. & Sethi, A. Advantages, limitations and recommendations for online learning during COVID-19 pandemic era. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 36(COVID19-S4), S27–S31 (2020).

Baczek, M., Zaganczyk-Baczek, M., Szpringer, M., Jaroszynski, A. & Wozakowska-Kapton, B. Students’ perception of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: A survey study of Polish medical students. Medicine (Baltimore) 100(7), e24821 (2021).

Dhar, P., Rocks, T., Samarasinghe, R. M., Stephenson, G. & Smith, C. Augmented reality in medical education: Students’ experiences and learning outcomes. Med. Educ. Online. 26(1), 1953953. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2021.1953953 (2021).

Alkhateeb, N. E., Ahmed, B. S., Al-Tawil, N. G. & Al-Dabbagh, A. A. Students and examiners’ perception of virtual medical graduation exam during the COVID-19 quarantine period: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 17(8), e0272927 (2022).

Arekat, M. et al. Evaluation of the utility of online objective structured clinical examination conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 28(13), 407–418. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S357229 (2022).

Motkur, V., Bharadwaj, A. & Yogarajah, N. Is online objective structured clinical examination teaching an acceptable replacement in post-COVID-19 medical education in the United Kingdom?: A descriptive study. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 19, 30. https://doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2022.19.30 (2022).

Lee, R. et al. A systematic review of simulation-based training tools for technical and non-technical skills in ophthalmology. Eye (Lond). 34(10), 1737–1759. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-020-0832-1 (2020).

Najafi, A., Babaei, S., Sadoughi, M. M., Kalantarion, M. & Sadatmoosavi, A. Impact of artificial intelligence on the knowledge, attitude, and performance of ophthalmology residents: A systematic review. J. Ophthalmic Vis. Res. 20, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.18502/jovr.v20.17029 (2025).

Fang, Z., Xu, Z., He, X. & Han, W. Artificial intelligence-based pathologic myopia identification system in the ophthalmology residency training program. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2022.1053079 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the ophthalmologists that generously agreed to participate in this study and we gratefully thank Ms.Nelisa Thornsri (Research Department, Mahidol University) for her valuable guiding and performing the statistical analyses.

Funding

This study was supported by Siriraj Research Fund, Grant number (IO) R016431078, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital Mahidol University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WC—Study conception and design; data collection, management, and interpretation; writing of the first draft of the manuscript, and final critical review; JC—data collection, writing of the first draft of the manuscript, and final critical review; WK—data collection and final critical review; PH—data collection and final critical review; AM—data collection and final critical review; OSa—data collection and final critical review; SV—data collection and final critical review; RC—data collection and final critical review; PP—data collection and final critical review; TK—data collection and final critical review; PK—data collection and final critical review; SS—data collection and final critical review; SSa—data collection and final critical review; VP—data collection and final critical review; WD—data collection and final critical review; NC—Study conception and design; funding acquisition; study supervision; writing of the first draft of the manuscript, review of the manuscript for important intellectual content; and, acceptance of the role of corresponding author. All authors have read and approved the version of the manuscript submitted for journal publication, and each author agrees to be personally accountable for his or her own contributions to the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chuenkongkaew, W., Chalermpong, J., Kiddee, W. et al. Perception of online learning, knowledge assessment, and clinical skills among third-year ophthalmology residents studying during the COVID-19 pandemic in Thailand. Sci Rep 16, 5252 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35674-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35674-4