Abstract

This study aimed to employ supervised models for predicting pressure injuries in hospitalized patients using data collected within the first eight hours after admission, thus providing a tool for early assessment and prevention. The dataset included 446 patients admitted to multiple hospital wards at Félix Bulnes Clinical Service Hospital in Santiago, Chile, between January and December 2022. After preprocessing the data through imputation and feature selection, we evaluated five machine learning models, Decision Tree, Logistic Regression, Random Forest, Extreme Gradient Boosting, and Support Vector Machines, using cross-validation. Their performance was assessed using accuracy, precision, recall, and AUC. The incidence of pressure injuries was 18.8%, with 9.86% occurring in the adult medical-surgical unit. Key risk factors identified included size, weight, total risk score, hospital ward, dependency risk, use of anti-decubitus mattresses, physical restraints, incontinence, and pre-hospital pressure injuries (p-value < 0.01). The Random Forest model showed the best performance, achieving an AUC of 82.4%, an accuracy of 82.5%, a specificity of 86.9%, and an adjusted precision of 93.3%. These results indicate that predictive models based on early nursing records can support clinical decision-making and enable timely prevention of pressure injuries in hospitalized patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A pressure injury (PI) corresponds to an area of skin or underlying tissue that exhibits localized damage or trauma, usually over a bony prominence, as a result of prolonged pressure, either alone or in combination with shear forces. When this damage occurs over a bony area and leads to skin breakdown, it is commonly called a “pressure ulcer”1.

PIs affect more than 10% of hospitalized adults, with Stage I wounds being the most frequent and preventable forms2. These injuries are highly prevalent among critically ill or immobilized patients, especially during early hospitalization, and are associated with increased morbidity, prolonged hospital stays, and significant healthcare costs3. In particular, emergency and intensive care units represent high-risk environments due to the limited mobility of patients, physiological instability, and high dependency on medical care4.

The economic burden of PI is substantial. In the United States alone, the total annual cost of acute care attributable to hospital-acquired pressure injuries is estimated to exceed $26.8 billion5. Beyond their financial impact, these injuries adversely affect multiple dimensions of health-related quality of life, including physical functioning, emotional well-being, and social participation6. Consequently, early identification and prevention strategies are critical for reducing the incidence and impact of PI7.

A wide range of clinical risk factors has been consistently associated with the development of PI. Advanced age, comorbidities, reduced tissue tolerance, and impaired mobility are widely recognized as key determinants8,9. Additional contributors include decreased sensory perception, nutritional deficits, and high levels of care dependency3,10. Incontinence and moisture-associated skin damage also compromise skin integrity and significantly increase the risk of PI11,12. Similarly, the use of vasopressors (commonly administered in critical care) has been strongly linked to impaired perfusion and tissue ischemia3,13. In contrast, preventive strategies such as pressure-relieving surfaces and systematic repositioning have proven effective in reducing PI incidence14,15.

Medical device-related PIs have increasingly been recognized as a significant source of harm. These injuries result from prolonged contact with invasive or noninvasive devices and are particularly common in intensive care settings, where patient immobility and continuous equipment use are prevalent16,17,18.

Despite the use of standard tools such as the Braden Scale, traditional risk assessment methods cannot fully capture the complexity of patient conditions. These tools often rely on subjective assessments and may underestimate risk, especially in patients with incontinence12, intermediate Braden scores10, or obesity-related vulnerabilities19,20. These limitations highlight the need for complementary, data-driven approaches that can enhance early risk stratification and guide targeted preventive care. We therefore propose a machine learning (ML) framework that uses early nursing records to anticipate PI development and support timely, targeted prevention.

In recent years, ML techniques have shown considerable promise in predicting PIs. These models can capture complex, non-linear relationships among clinical variables and have often outperformed traditional risk assessment tools, particularly when using data from electronic health records (EHRs). However, many existing models require a large number of variables, including laboratory tests and longitudinal data, which are often unavailable during the early hours of admission, especially in emergency care settings21.

In this paper, we propose an ML-based predictive approach that relies exclusively on basic nursing records collected within the first eight hours after hospital admission. In line with the TRIPOD guidelines, this study is designed as a prognostic prediction model, aiming to estimate the probability that a patient will develop a PI during hospitalization, based on predictors collected at baseline. Unlike diagnostic models, which identify an existing condition at the time of assessment, prognostic models estimate the future risk of an event. This time frame aligns with institutional protocols for the initial clinical evaluation and reflects realistic operational workflows.

We acknowledge that PI may arise through different pathways, depending on patient characteristics and hospital wards. Although ward-specific models could capture such heterogeneity, they require large, stratified datasets, which increase operational complexity for deployment. Given the need for a single early warning tool, we developed a unified model that covers multiple wards. This approach allows for consistent integration into hospital-wide EHRs and triage systems while still accounting for ward-level variation through the inclusion of the hospital ward as a feature.

Our approach bridges the clinical need for early prediction of PI with a data-driven solution by leveraging routinely collected information to build a practical, interpretable, and high-performance ML model.

Related works on machine learning for pressure injury prediction

Numerous studies have explored the application of ML and statistical techniques for PI prediction, often using features derived from demographic variables, clinical records, EHRs, laboratory test results, and medical assessments. Several systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and scoping reviews have also summarized current research directions and efforts in this field22,23,24,25,26.

ML techniques are particularly well-suited to capture the complex, nonlinear interactions that characterize clinical data27. In the context of PI prediction, models have been trained using EHRs data from various hospital units21,28,29, with the choice of algorithm typically adapted to the data structure and availability. Approaches have ranged from Bayesian networks30, mixed-variable graphical models31, and regression trees32 to deep learning frameworks33.

Other efforts have explored non-traditional data sources to enhance model performance. These include estimated skin temperature derived from imaging or sensors34, as well as unstructured clinical notes integrated through natural language processing techniques35.

Additionally, many models incorporate laboratory features such as oxygen saturation, white blood cell count, protein levels, blood glucose, and hemoglobin concentration to improve classification accuracy21,36,37,38.

Aims

This paper aims to develop efficient and interpretable ML-based models that predict PI risk using only basic nursing information available within the first eight hours of hospital admission. The input data reflect routine clinical information collected prior to laboratory tests or the use of invasive devices, in alignment with initial nursing evaluation protocols.

The proposed approach contributes by demonstrating that low-complexity, early-stage data can yield highly predictive performance, supporting timely and resource-efficient decision-making. This addresses a notable gap in the literature, as most existing models rely on extensive feature sets drawn from laboratory results, detailed clinical histories, and longitudinal records28,36,37,39.

Although some studies have explored parsimonious models, they generally focus on later time windows, such as predicting PI within seven days after admission, or on specific subpopulations, such as pediatric patients40. Other authors have used PI data not as a target variable but as a predictor of related outcomes, such as functional recovery or risk of falling41,42. In contrast, our paper explicitly focuses on the early prediction of PI using data available within a clinically actionable time-frame, with a design intended for general hospital populations.

Methods

This section outlines the methodological steps used to preprocess the data, select relevant features, train and evaluate ML models, and interpret the outputs. The steps are presented in Fig. 1, with details for each provided in the following paragraphs.

Statistical analysis

Data preprocessing and ML model development were performed using Python 3.11.5, while statistical analyzes and performance comparisons were conducted in R 4.4.2. Descriptive statistics for categorical variables, considering the target variable, are presented as absolute frequencies, whereas continuous variables are reported as means with standard deviations. All preprocessing steps were implemented using Scikit-learn Pipelines to ensure that each transformation was fit exclusively on the training folds and never on the validation folds, thereby preventing any form of data leakage.

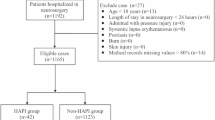

Study population and data collection

An observational, cross-sectional design was employed for this study, with data collected from a tertiary hospital located in an urban area of Santiago, Chile. The sample size was calculated using a 95% confidence level, a 5% margin of error, and an anticipated 20% loss, yielding an estimated sample of approximately 500 patients. Data were collected using a convenience sampling method conducted by healthcare professionals across different hospital wards. After excluding atypical data and duplicate entries, the final sample comprised 446 patients.

Data were collected using structured forms and patient records (data collection instruments for the prevalence study). These instruments were designed to capture information on both patient-related factors and those associated with the development of PIs. The data collection form was validated by a panel of experts who guided the mapping of free-text terms and shorthand notations into discrete, clinically meaningful categories. Furthermore, they validated the rules used for resolving conflicting entries. This process was divided into four sections: (i) demographic characteristics, (ii) clinical parameters at the time of admission, (iii) laboratory and diagnostic tests requested by the physician, with results available within 24 h of admission, and (iv) variables related to PIs, including PI risk, preventive measures implemented, and severity of tissue damage.

Dependency risk was classified using the Clasificación de Riesgo-Dependencia (CUDYR), a validated nursing care management instrument adopted by the Chilean Ministry of Health in 2008. This tool categorizes hospitalized patients according to their care needs, supporting resource allocation and clinical management. Categories range from A (highest dependency) to D (lowest dependency), with sublevels (1–3) indicating total dependence, partial dependence, and partial autonomy, respectively.

The definition of PI was established according to the criteria set by the National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPIAP). The assessment of PI presence was dichotomous: patients were classified as having no PI if they presented no area of skin or tissue meeting the NPIAP definition, including cases of intact skin with transient, blanchable erythema. Conversely, patients were classified as having a PI if at least one lesion was identified, regardless of stage (Stage 1 to Stage 4 or suspected deep tissue injury). Thus, the identification of a single PI at any anatomical site was sufficient to classify the case as positive43.

As the data were gathered during the first eight hours after hospital admission, they correspond exclusively to the initial basic nursing information collected upon entry. This information was used as the predictive baseline, independent of whether patients subsequently underwent surgery or were transferred to another unit. At this stage, surgical procedures are not typically scheduled or performed. Any PI identified within this initial eight-hour window was classified as a pre-hospital PI and was excluded from the outcome definition of hospital-acquired PI. Therefore, the predictive models are based exclusively on early admission data, ensuring prognostic validity before any subsequent interventions, such as surgery, could influence the PI risk.

It is important to clarify that the initial basic nursing information corresponds to standardized nursing assessments that are systematically applied to all patients upon admission, regardless of their medical diagnoses. These variables capture clinical information independent of the admission condition, ensuring a comparison between heterogeneous patient groups. In addition, because these assessments are performed at admission, they can support the early allocation of nursing resources for preventive care.

Data preprocessing

The data wrangling and preprocessing stage involved transforming unstructured nursing data into structured datasets suitable for analysis. Relevant nursing documentation was extracted from the Hospital Information System (HIS) for each patient record. From this source data, key clinical concepts associated with PI development were identified. We worked closely with expert clinicians to convert text-based information into standardized, structured variables.

Given that HIS records often include multiple entries per patient, we implemented a comprehensive aggregation and conflict-resolution strategy. This process applied time-window aggregation to group entries within clinically meaningful periods. For categorical data, we resolved conflicts by selecting the most clinically severe or critical value. For frequency-based features, values were aggregated through summation to reflect the intensity or frequency of relevant events.

To address the missing values in the structured dataset, we applied imputation techniques based on the variable type. For continuous variables, the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) method was used to estimate and replace missing values based on similarities among patient profiles. This method works by replacing a missing value by looking at the k most similar rows (neighbors) in the dataset. Similarity is measured by Euclidean distance using the non-missing features. Given that the method relies on distance calculations, a scaling procedure was conducted to mitigate the dominance of features with different scales.

The KNN method requires choosing the best k to calculate similarities. For this purpose, artificial missingness values were created. It works by randomly masking a subset of non-missing entries and applying the KNN using different values of k. Later, the imputed values were compared to the original known values, and the k that gives the lowest error was chosen.

For categorical variables, frequency-based imputation was performed, incorporating contextual information such as the patient’s hospital ward and gender to maintain clinical relevance.

Feature selection

The feature selection process was conducted using the chi-square \((\chi ^2)\) test for categorical variables. This test is suitable for evaluating the relationship between categorical features and a categorical target variable by assessing whether there is a statistically significant association between them. A low \(p-\)value indicates that the feature is likely associated with the categories of the target variable.

For numerical features, the \(t-\)test was applied. This test evaluates whether two independent samples differ by comparing the means of the two groups while considering their variances. A low \(p-\)value indicates that the distributions across the two categories differ, suggesting that the feature may help predict the outcome.44.

Machine learning models

Five supervised ML models for binary classification were evaluated. These included tree-based models: Classification Decision Tree (DT), Random Forest (RF) for ensemble learning, and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGB) for sequential learning; a logit model: Logistic Regression (LR); and margin-based models: Support Vector Machines (SVM) with different kernel types. This selection reflects a diverse set of learning paradigms suitable for capturing both linear and nonlinear patterns in clinical data. All of these models were fitted using the Scikit-Learn package version 1.7.145.

Ensemble learning can also combine heterogeneous models; however, in this study, we focused on tree-based approaches, such as RF. The selection of RF over other ensembling techniques is based on its balance of complexity and interpretability. Mixed ensembling combines models with different structures, making the overall ensemble harder to interpret compared to RF. In addition, training diverse models incurs higher computational costs, as each model requires distinct optimization procedures and sets of hyperparameters. Mixing heterogeneous models also increases the risk of overfitting in small datasets (fewer than 500 samples), since there is not enough data to train multiple models and perform cross-validation reliably46. Additionally, it demands careful tuning, whereas RF follows a more standardized tuning process47.

To ensure optimal model performance and fair comparisons between classifiers, grid search hyperparameter optimization was performed for each model. This process was embedded within a \(k-\)fold cross-validation loop. Hyperparameters were chosen based on common best practices and systematically explored to minimize the risk of underfitting or overfitting. Table 2 summarizes the ranges of specific hyperparameters explored for each algorithm. The first column indicates the model, while the second and third columns present the hyperparameters and their respective value ranges. This optimization step was essential, as model performance is influenced not only by data quality but also by the appropriate calibration of model complexity. Tuning these hyperparameters enhances the robustness, generalizability, and clinical utility of the predictive models48.

It is worth noting that for the models, class imbalance was addressed by applying balanced class weights based on the frequency of each category. This feature prevents the model from ignoring the minority class in the presence of imbalanced classes. It works by computing a weighted loss (WL), as shown in(1).

Where n denotes the sample size, \(w_{y_i}\) is the weight for the true class of sample i, and l is the model’s loss, which depends on its specific implementation (e.g., log-loss for logistic regression, hinge loss for SVM, scaled POS weight for XGB)49.

This approach helps prevent the models from favoring the majority class and improves their ability to accurately classify minority class instances49. The decision to use this approach instead of artificial sampling methods is primarily due to the limited sample size. In small datasets, synthetic samples may cause overfitting by introducing unrealistic patterns that are not present in the actual data. This occurs because artificial sampling techniques, such as SMOTE, assume sufficient density in the feature space for reliable interpolation, a condition that may not be met in smaller datasets50.

Furthermore, feature importance analysis was conducted to enhance the interpretability of the ML models, particularly those based on tree structures such as DT and RF. This procedure quantifies the relative contribution of each input variable to the model’s predictive performance by measuring the reduction attributed to splits on that feature across all decision nodes. Features with a higher importance value highlight a greater influence on the model’s decision process, providing insights into which variables most strongly drive the prediction of the outcome51. The computed importance values were later used for clinical interpretation and to identify key risk factors associated with patient outcomes.

Evaluation criteria

The evaluation metrics result from applying the models and obtaining classifications on the evaluation set. Accuracy, precision, Area Under the Curve (AUC), Recall, and Specificity are calculated. These metrics are calculated by a \(k-\)folds cross-validation process to mitigate issues related to overfitting and randomness in the results. The average, minimum, and maximum values of the scores were then computed and compared across models to assess their performance and reliability.

To compute these metrics, consider a target variable with two outcomes in a binary classification task, \(y_i=\{T;N\}\),and a predicted outcome in the form \(\hat{y}_i=\{T;N\}\). This leads to four possible outcomes due to the combination of the actual and predicted values. The combinations are shown in Table 1.

The accuracy is computed as the fraction of the classes correctly predicted out of the total predictions, as shown in (2).

The precision, also called the positive predicted value, measures the proportion of predicted positive values that are actually positive. Its calculation is shown in (3),

The recall, also known as the True Positive Rate (TPR), measures the proportion of actual positive instances that are correctly identified. Its calculation is shown in (4)

The specificity, also known as the true negative rate, measures the ability of a model to classify negative classes. It works as a trade-off with the recall metric. Its calculation is shown in (5)

The AUC is calculated from the ROC curve, which plots the TPR on the y-axis and the False Positive Rate (FPR) on the x-axis at various classification thresholds. It measures how well the model separates positive classes from negative classes at several decision thresholds. A value near 1.0 indicates a perfect classifier, while a model below 0.5 denotes a model worse than randomness. The TPR and FPR metrics are shown in (6) and (7),

Later, the AUC can be computed as shown in (8)

The accuracy is used as the baseline performance across the models tested, along with the AUC metric. Furthermore, a high precision indicates that the results are trustworthy, while recall and specificity indicate the rate of false alarms that the model might have triggered, depending on the class being considered.

Post-hoc classification threshold optimization

The classification algorithms can be set to retrieve the probability that a data point belongs to a particular class (0 or 1) given a set of features \({\textbf {x}} \in \mathbb {R}^{p}\), where \(\hat{p}\):

The default classification rule assigns a label based on a fixed threshold \(t = 0.5\):

Let \(\hat{p}_i\) be the predicted probability for a model, and let \(\hat{y}^{t}\) be the predicted labels for the threshold t. We define precision shown in (3) as a performance metric. The goal is to find the threshold that maximizes this metric in the validation set, as shown in (11). This adjustment to the threshold yields adjusted performance metrics for binary classification.

The selection of \(t^{*}\) relies on a grid-search setting conducted with the trained model. This process considers an exhaustive search of the \(t^{*} \in [0,1]\) embedded within the cross-validation procedure. To prevent data leakage, the selection was carried out using an out-of-fold procedure. Once this optimization process is conducted, the adjusted precision is defined as shown in (12).

Where \(TP^{*}\) and \(FP^{*}\) denote the correctly predicted positive cases and the incorrectly predicted negative cases with the new threshold \(t^{*}\) as defined in (10), In this way, we can define the adjusted accuracy as shown in (13) in the same manner as (12) to highlight the change in the classification process with this metric as a baseline comparison.

Once the metrics shown in (2), (3), (4), (5), (8), (12), and (13) are calculated per fold, the Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn’s test are conducted to determine whether the differences in performance are statistically significant. These tests are appropriate for performing multiple pairwise comparisons while controlling the type I error during the process52. For the Dunn test, the null hypothesis for each pairwise comparison is that there is no difference between the groups being compared. If the \(p-\) value obtained from the pairwise test is small, the differences observed are statistically significant53.

The decision to optimize the classification threshold for higher precision is based on operational considerations in the resource-constrained environment of hospitals. In such environments, excessive false positive alerts can overload nursing staff and potentially reduce adherence to preventive interventions. Prioritizing precision increases the probability that a patient is truly at high risk, allowing for a more efficient allocation of preventive resources.

Results

This section reports the main findings. It includes descriptive statistics, univariate and multivariate analyzes, model performance metrics, and clinical interpretation based on feature importance. Figure 2 displays the percentage of missing values per column in the dataset. The weight column has the highest proportion of missing values, at about 50%. Age has approximately 5% missing values, while size and risk each have about 2.5% missing values. Nutritional management, position assistance, skin treatment, and pre-hospital PI show slightly above 0% in terms of missingness. Performing a complete case analysis would eliminate about 55% of the data.

Occurrence of pressure injuries

As defined in the Methods section, any PI identified within the first eight hours after admission was classified as pre-hospital and excluded from the outcome. Therefore, all reported results refer exclusively to hospital-acquired PIs occurring after this initial assessment window. The total incidence of PIs among hospitalized patients was \(18.8\%\). This corresponds to about 80 cases with PI development and 360 cases without. Half of the injuries occurred in the adult medical-surgical unit \((9.86\%)\), followed by the adult surgical unit \((3.36\%)\), and the adult intermediate care unit \((2.24\%)\). Approximately \(54.7\%\) of the patients were male. The mean age was 54 years for men and 46 years for women.

Univariate analysis of risk factors for pressure injuries

Table 3 presents the results of the univariate analysis for both categorical and numerical variables in relation to the development of PIs. The first column lists the variables. The second and third columns display the mean and standard deviation for numerical variables, or frequency counts for categorical variables, in patients with and without PIs. The fourth column shows the test statistic (t-test for numerical variables, \(\chi ^2\) for categorical ones), and the fifth column provides the corresponding \(p-\) value. All reported values correspond to the features after applying the imputation procedure, which was performed using the KNN method with \(k=4\) following its evaluation.

Significant factors include the hospital ward, dependency risk, usage of an anti-decubitus mattress, positional assistance, physical restraints, presence and type of incontinence, injuries due to adhesives, use of invasive devices, and the presence of pre-hospital PIs. Among the numerical features, the size (the height of the patients, measured in centimeters), the weight (measured in kilograms), and the total risk score were statistically significant. This analysis led to the selection of 13 predictive features for subsequent modeling. Details on the distribution of numerical features before and after data imputation are provided in Supplementary Material 1, Fig. A1, and Table A1.

Independent risk factor analysis of pressure injury

The significant features identified in the univariate analysis were encoded for model input. A process of one-hot encoding was applied to convert categorical features into dummy variables, with one category removed from each feature to prevent collinearity among categorical variables54. For numerical features, a standard out-of-fold scaling procedure was applied to address differences in variable scales55. This process was embedded within an out-of-fold setting to avoid data leakage from the training dataset to the testing dataset. Let \(x^{j}\) represent the numerical features that explain PI. The scaling procedure was conducted as shown in (14).

This transformation ensured a zero mean and unit variance, which is critical for algorithms such as SVM and LR, as they are sensitive to feature magnitude. This is mainly due to their use of distance measures and coefficient penalties, respectively55.

Model performance

The model performance metrics are summarized in Table 4, which presents the adjusted performance metrics as defined in (11), along with the traditional metrics. The DT model had the lowest AUC (76.9%) and precision (40.9%), but the adjusted precision improved (71.6%), reflecting the results of the calibration step. The accuracy (74.9%) and adjusted accuracy (81.8%) were moderate, while recall and specificity were balanced (\(\sim\) 74%). The LR model shows better overall discrimination, as its AUC (81.7%) is better. The precision (44.3%) is low but better than that of the DT model. The recall and specificity are balanced (\(\sim\) 75%). The RF model had the highest AUC (82.4%) denoting the best discrimination ability among the models tested. Furthermore, it shows higher precision (66.3%) and adjusted precision (93.3%) compared to the DT and LR models. The recall (62.5%) is lower, but the specificity (86.9%) is the highest, indicating a strong ability to identify negatives. The SVM had a similar AUC (80.8%) to LR, along with low precision (42.5%) and adjusted precision (80.9%). Its accuracy (76.0%) and adjusted accuracy (82.7%) are moderate, while it is balanced in terms of recall and specificity (\(\sim\) 75.0%). The XGB model had a similar AUC (81.9%) to the RF model, with high precision (62.3%) and adjusted precision (90.8%). It had the best accuracy (83.2%) and adjusted accuracy (83.2%), along with the lowest recall (40.6%) and the highest specificity (93.1%), denoting a conservative model with the ability to correctly identify the negative class.

It is worth noting that for all models, the adjusted threshold values are \(0.2\pm 0.1\), highlighting the importance of optimizing this parameter to improve precision control and to manage class imbalance more effectively compared to relying on default classification thresholds. Details on the adjusted thresholds can be found in Supplementary material 2, Fig. A1. Furthermore, while this precision-oriented threshold optimization reduces false-positive alerts, it necessarily entails a trade-off with sensitivity, potentially leaving some high-risk patients unflagged. This consideration is further discussed in the context of clinical implementation.

The selected hyperparameters for each model are presented in Supplementary Material 2, Table A2, showing the different paradigms and structures addressed to handle the classification task. Additionally, a robustness check was conducted by fitting the models without the weight feature. It is worth noting that model performance remained stable after excluding the weight variable, indicating that predictive discrimination was not driven solely by this feature, despite its high missingness. Details of the model performance without this feature are provided in y Material 2, Table A1.

The Kruskal–Wallis test was performed to compare models across multiple performance metrics. Precision, accuracy, recall, and specificity all showed statistically significant differences among the models \((p-\)value \(<0.05\)), indicating that model choice had a meaningful impact on performance. Since precision, recall, and specificity differ significantly, the models vary in their trade-offs between false positives and false negatives, which carry important clinical implications. In contrast, the lack of significance in AUC suggests that, while overall discrimination is similar across thresholds, the operational performance differs between models.

Pairwise comparisons using Dunn’s test revealed that RF significantly outperformed DT, SVM, and LR in terms of accuracy, precision, recall, and specificity at the 95% confidence level. Furthermore, RF significantly outperformed the XGB model in recall (\(p-\)value: 0.057). This suggests that the RF model better identifies true positive cases, which is particularly important in clinical settings where missing positive cases can be costly.

Due to the consistently higher discrimination and precision metrics shown by the RF model, its advantages in predictive performance outweigh the variability, supporting its selection as a leading candidate for prospective validation and eventual deployment.

Figure 3 displays the ROC curves obtained through the cross-validation process for the RF model. The model showed consistently strong discrimination ability across folds. The ROC curves rise steeply on the left, showing high true positive rates with low false positive rates. Overall, the curves remain well above the diagonal line, confirming that the model performs better than random guessing. This demonstrates a solid ability to distinguish between the positive and negative classes. The differences in the AUC across folds are expected and consistent, with all values above 0.8 and only small variations.

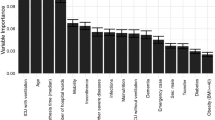

Feature importance and clinical interpretation

To enhance interpretability, we assessed the relative importance of input features in the RF and DT models, as their calculation is straightforward. As shown in Fig. 4, the DT model assigns the greatest importance to patient weight, followed by the total risk score and physical restraints. The RF model prioritized the total risk score, patient weight, and patient size. In both models, the absence of invasive devices, the use of anti-decubitus mattresses, the presence of pre-hospital PI, and the absence of incontinence had similar impacts on classification performance.

Other relevant features that have a strong impact on the RF model include position assistance, dependency risk, and fecal incontinence. These findings are consistent with established clinical risk factors. They highlight the potential of this analysis to support early decision-making processes and early-stage assessments. In practice, identifying high-importance features enables clinical staff to prioritize interventions during initial patient evaluations.

Figure 5 shows the distribution of predicted risk across four incontinence types. Patients with fecal incontinence exhibit the highest median risk and the widest range, indicating both a higher central tendency toward higher risk and variability within this group. Mixed incontinence shows a lower median risk but includes several high-risk outliers, suggesting that while most individuals in this category have a relatively low predicted risk, a subset faces substantially elevated values. Urinary incontinence and no incontinence groups display similar median risks, both slightly below the overall average; however, the no incontinence group shows a wider spread toward higher values. This indicates the influence of additional risk factors beyond incontinence type. Overall, Fig. 5 suggests that incontinence type is associated with distinct patterns of predicted risk, with fecal incontinence standing out as the most strongly linked to higher risk levels.

Figure 6 shows the distribution of predicted risk across various hospital wards. Most wards have median risk values clustered around or below the average; however, notable differences are observed. The Adult Medical-Surgical and Recovery wards show greater variability, with outliers indicating subsets of patients at significantly elevated risk of PI development. Neonatal Intensive Care and Adult Intensive Care units also display wide risk distributions, suggesting heterogeneous patient profiles with varying severity levels. In contrast, Pediatric Surgery and Pediatric Medical-Surgical wards show lower median risks and tighter ranges of variability, pointing to more consistent and lower risk profiles.

Overall, these findings highlight that patient risk is not uniformly distributed across wards. Critical care and high-complexity units tend to show greater variability and a higher prevalence of extreme-risk cases, requiring special attention.

Discussion

This study evaluated the performance of five ML models for the early prediction of PI across multiple hospital wards. Among them, the RF model achieved the highest AUC and accuracy. This demonstrates superior reliability across cross-validation folds. Although LR reached a similar AUC, its higher variability between folds reduced its robustness. Notably, only tree-based models reached a precision of 100% by at least one fold.

The selected features for modeling align with the risk factors extensively reported in the literature. For example, several studies have analyzed the effectiveness of anti-decubitus mattresses in preventing the development of PI56. Regarding physical restraint, several studies have shown its association with a higher probability of PI development in hospital wards. This is largely explained by reduced physical activity while standing in the wards57,58. Incontinence is another common factor associated with PI and skin complications. Reviews and meta-analysis have shown that patients with mixed incontinence (urine and feces) present a higher prevalence of PI than other patients. This is mainly due to the development of dermatitis and other skin problems58,59,60. Similarly, injuries caused by medical adhesives, particularly in neonates, can result in substantial skin damage61. The use of invasive devices also contributes to PI risk due to localized tissue stress and ischemia62.

Compared to previous studies, this work presents four main advantages: (1) the use of basic nursing records collected within the first eight hours of hospitalization, allowing early prediction and proactive decision-making based on risk metrics before laboratory tests or major interventions are performed; (2) the development of a compact model composed of only 13 statistically selected features, supporting interpretability and clinical integration; (3) the ability to generate actionable and timely predictions aligned with hospital protocols; and (4) similar results in terms of classification performance compared to applications in the literature.

Previous ML-based PI prediction models often depend on a larger number of features, including laboratory results, detailed clinical histories, or longitudinal monitoring, which limits their feasibility during the early hours of admission28,29,37. For instance, studies that integrate laboratory tests and other clinical procedures have reported precisions around 80%, AUC values close to 90%, and accuracies near 80%63,64,65. While these results are strong, they rely on information that is not routinely available at admission. In contrast, our study shows that similar predictive performance can be achieved with nursing-based features collected at admission. This makes the model more practical for early prognosis.

These results highlight the strength of parsimonious models that focus on early, statistically validated features. By avoiding dependence on laboratory or longitudinal data, the model becomes suitable for real-time implementation in hospitals. It can also be applied in other high-turnover care environments. Importantly, the proposed model is intended to support, rather than replace, clinical judgment, serving as a decision-support aid to complement professional nursing assessment.

Clinical implications and applicability

The proposed approach offers a practical solution for predicting PI risk within the first eight hours after admission, based on routine nursing observations. Its simplicity and reliance on readily available clinical information facilitate seamless integration into existing workflows across diverse hospital wards. With demonstrated performance using 13 clinical variables, the model could be embedded within EHR systems or nurse-led triage systems to produce real-time risk alerts, along with decision-support dashboards that simplify integration for non-technical users.

For a triage use case, the system can assign PI risk scores in real-time settings, triggering high-risk patients to staff for immediate preventive measures or closer monitoring. These alerts would allow healthcare teams to prioritize preventive interventions for patients identified as high risk during their first hospital hours66. This, in turn, enables timely preventive strategies and more frequent skin assessments.

It is worth noting the barriers to implementation in settings with limited digital infrastructure. EHR systems without built-in analytic modules or with limited server capacity for running ML models in real time may restrict the applicability of the methodology. Other operational barriers include the need for adequate staff training to interpret results and the risk of alert fatigue if triggers are too frequent or non-specific67.

Furthermore, the model addresses a key limitation of traditional risk stratification tools: subjectivity. By automating predictions and standardizing risk evaluation, it reduces inter-rater variability and enhances consistency in clinical decision-making.

Implementation pathways will vary depending on the infrastructure. In digitally mature health centers, real-time integration is feasible; whereas, in low-resource settings, simplified offline scoring tools or batch processing may be more practical. Successful deployment will require clear alert routing, actionable response protocols, strategies to minimize alert fatigue, and continuous updating of the model parameters to prevent data drift and maintain performance over time68.

By prioritizing precision over specificity or recall, our approach aims to minimize unnecessary preventive interventions in patients unlikely to develop PI, thereby preserving nursing resources and reducing alert fatigue. This trade-off is particularly relevant in high-demand hospital wards, where staff-to-patient ratios are often low, and preventive measures, such as frequent repositioning or the use of special mattresses, are resource-intensive. While this choice may result in some high-risk patients not being flagged, the operational benefits and higher confidence in alerts may enhance clinical adoption and support the long-term sustainability of the tool.

In clinical deployment, small variations in performance across patient subgroups are acceptable when the overall predictive ability remains consistently strong. Among all tested algorithms, RF achieved the highest discrimination and precision, making it the most effective at correctly identifying patients at high risk for developing a PI. Although its variability across folds was slightly higher than that of other models, this trade-off is outweighed by its superior operational performance and clinical utility.

Limitations

Although the proposed model demonstrates promising performance, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, while we included a comprehensive basic set of nursing records, it is possible that additional variables could further improve discrimination and predictive performance. For example, basic EHRs data, such as allergies, medications, cognitive status, or medical history, could enhance predictive accuracy without compromising the principle of relying on information available within the first eight hours after admission.

Second, the study relied on a convenience sampling procedure, which presents inherent limitations and resulted in a relatively small sample size. Although the results were evaluated in a cross-validation setting, the limited sample size constrains the generalizability of the findings to other centers with different care typologies, infrastructures, or patient populations. Furthermore, the utilization of convenience sampling may have introduced bias and limited the generalizability of the model to broader or more diverse clinical populations, as some groups of patients might be overrepresented or underrepresented.

While the models demonstrated promising performance within the current sample, external validation using independent datasets from different clinical settings is essential to assess their robustness and applicability across broader populations. This is highlighted not only by the convenience sampling procedure but also by the fact that the data were collected from a high-complexity hospital network, which may limit the model’s generalizability to other settings. External validation in different institutions and healthcare systems remains necessary to confirm its broader applicability.

The inclusion of neonatal and pediatric populations should be acknowledged as a limitation. Although these groups were part of the dataset, they presented no cases of PI, which may artificially increase overall model accuracy without improving clinical relevance. In practice, newborns and children are at very low risk of PI and are typically not considered for preventive interventions.

Finally, while the model performs well in prediction, its real-world impact on patient outcomes remains to be tested. Future research should assess its integration into practice and its effectiveness in reducing the incidence of PIs in real world settings through prospective validation trials. In addition, improved sampling procedures, such as increasing the sample size and including randomized methods, are needed to enhance statistical power, strengthen generalizability, and reduce selection bias. Furthermore, this improvement enables the application of ward-specific models, which may enhance the ability to capture specific features and heterogeneity across different ward typologies. A characteristic that is limited due to the sampling procedure conducted to retrieve the data in the current study.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the feasibility of developing high-performing, interpretable ML models for the early prediction of PI using only routine nursing records collected within the first eight hours of hospital admission. Unlike most previous research, which relies on extensive and often delayed clinical information, such as laboratory tests or longitudinal monitoring, our approach achieves competitive predictive performance with a streamlined set of 13 statistically selected features.

Data were collected from patients admitted to a hospital in Santiago, Chile, and included 13 features selected through univariate statistical analysis. Among the models evaluated, the RF model achieved the highest performance, with an AUC of 82.4%, a precision of 93.3%, and an accuracy of 82.9%.

These results support the feasibility of implementing efficient, interpretable, and parsimonious predictive tools in routine clinical practice. Such models may assist healthcare professionals in the timely identification and stratification of at-risk patients in various hospital wards, ultimately contributing to improved prevention strategies and patient outcomes. Nevertheless, this work should be regarded as an exploratory step toward future clinical deployment, requiring further external validation before being considered a definitive solution.

Data availability

The data sets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hajhosseini, B., Longaker, M. T. & Gurtner, G. C. Pressure injury. Ann. Surg.271, 671–679. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000003567 (2020).

Li, Z., Lin, F., Thalib, L. & Chaboyer, W. Global prevalence and incidence of pressure injuries in hospitalised adult patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud.105, 103546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103546 (2020).

Alderden, J., Rondinelli, J., Pepper, G., Cummins, M. & Whitney, J. Risk factors for pressure injuries among critical care patients: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud.71, 97–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.03.012 (2017).

Shahin, E. S., Dassen, T. & Halfens, R. J. Pressure ulcer prevalence and incidence in intensive care patients: a literature review. Nurs. Crit. Care13, 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-5153.2007.00249.x (2008).

Padula, W. V. & Delarmente, B. A. The national cost of hospital?acquired pressure injuries in the united states. Int. Wound J.16, 634–640. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.13071 (2019).

Liu, S., Rawson, H., Islam, R. M. & Team, V. Impact of pressure injuries on health?related quality of life: A systematic review. Wound Repair and Regeneration 33, https://doi.org/10.1111/wrr.13236 (2024).

Padilla, P. L., Hancock, E. L., Ruff, E. S., Zapata-Sirvent, R. L. & Phillips, L. G. Pressure Injuries, 367–376 (Springer International Publishing, 2021).

Cai, J., Zha, M., Yuan, B., Xie, Q. & Chen, H. Prevalence of pressure injury among chinese community?dwelling older people and its risk factors: A national survey based on chinese longitudinal healthy longevity survey. J. Adv. Nurs.75, 2516–2525. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14008 (2019).

Weng, P., Lin, Y., Seo, J. & Chang, W. Relationship between predisposing and facilitating factors: Does it influence the risk of developing peri?operative pressure injuries?. Int. Wound J.19, 2082–2091. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.13811 (2022).

Alderden, J. et al. Midrange braden subscale scores are associated with increased risk for pressure injury development among critical care patients. J. Wound, Ostomy Contin. Nurs.44, 420–428. https://doi.org/10.1097/won.0000000000000349 (2017).

Beeckman, D., Van Lancker, A., Van Hecke, A. & Verhaeghe, S. A systematic review and meta? Analysis of incontinence? Associated dermatitis, incontinence, and moisture as risk factors for pressure ulcer development. Res. Nurs. Health37, 204–218. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.21593 (2014).

Lachenbruch, C., Ribble, D., Emmons, K. & VanGilder, C. Pressure ulcer risk in the incontinent patient: Analysis of incontinence and hospital-acquired pressure ulcers from the international pressure ulcer prevalence™ survey. J. Wound Ostomy Contin. Nurs.43, 235–241. https://doi.org/10.1097/won.0000000000000225 (2016).

Kebapci, A. & Tilki, R. The effect of vasopressor agents on pressure injury development in intensive care patients. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs.83, 103630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2024.103630 (2024).

Gillespie, B. M. et al. Repositioning for pressure injury prevention in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.2020, https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd009958.pub3 (2020).

Shi, C. et al. Beds, overlays and mattresses for preventing and treating pressure ulcers: an overview of Cochrane reviews and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.2021, https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd013761.pub2 (2021).

Stellar, J. J. et al. Medical device-related pressure injuries in infants and children. J. Wound Ostomy Contin. Nurs.47, 459–469. https://doi.org/10.1097/won.0000000000000683 (2020).

Coyer, F., Cook, J.-L., Doubrovsky, A., Vann, A. & McNamara, G. Exploring medical device-related pressure injuries in a single intensive care setting: A longitudinal point prevalence study. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs.68, 103155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2021.103155 (2022).

Celik, S., Taskin Yilmaz, F. & Altas, G. Medical \(<\)scp\(>\)device?related\(<\)/scp\(>\) pressure injuries in adult intensive care units. J. Clin. Nurs.32, 3863–3873. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.16516 (2022).

Jia, Y.-J. et al. Body mass index and pressure injuries risk in hospitalized adult patients: A dose-response analysis. J. Tissue Viability33, 405–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtv.2024.06.006 (2024).

Ness, S. J., Hickling, D. F., Bell, J. J. & Collins, P. F. The pressures of obesity: The relationship between obesity, malnutrition and pressure injuries in hospital inpatients. Clin. Nutr.37, 1569–1574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2017.08.014 (2018).

Padula, W. V., Armstrong, D. G., Pronovost, P. J. & Saria, S. Predicting pressure injury risk in hospitalised patients using machine learning with electronic health records: a us multilevel cohort study. BMJ Open14, e082540. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-082540 (2024).

Zhou, Y., Yang, X., Ma, S., Yuan, Y. & Yan, M. A systematic review of predictive models for hospital?acquired pressure injury using machine learning. Nurs. Open10, 1234–1246. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.1429 (2022).

Toffaha, K. M., Simsekler, M. C. E. & Omar, M. A. Leveraging artificial intelligence and decision support systems in hospital-acquired pressure injuries prediction: A comprehensive review. Artif. Intell. Med.141, 102560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artmed.2023.102560 (2023).

Qu, C. et al. The predictive effect of different machine learning algorithms for pressure injuries in hospitalized patients: A network meta-analyses. Heliyon8, e11361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11361 (2022).

Pei, J. et al. Machine learning?based prediction models for pressure injury: A systematic review and meta?analysis. Int. Wound J.20, 4328–4339. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.14280 (2023).

Alves, J., Azevedo, R., Marques, A., Encarnação, R. & Alves, P. Pressure injury prediction in intensive care units using artificial intelligence: A scoping review. Nursing Reports15, 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15040126 (2025).

Huang, Y., Li, J., Li, M. & Aparasu, R. R. Application of machine learning in predicting survival outcomes involving real-world data: a scoping review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol.23, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-023-02078-1 (2023).

Nakagami, G. et al. Supervised machine learning-based prediction for in-hospital pressure injury development using electronic health records: A retrospective observational cohort study in a university hospital in japan. Int. J. Nurs. Stud.119, 103932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103932 (2021).

Nguyen, K.-A.-N. et al. Electronic-medical-record-driven machine learning predictive model for hospital-acquired pressure injuries: Development and external validation. J. Clin. Med.14, 1175. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14041175 (2025).

Charon, C., Wuillemin, P.-H., Havreng-Théry, C. & Belmin, J. One month prediction of pressure ulcers in nursing home residents with bayesian networks. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc.25, 104945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2024.01.014 (2024).

Walther, F., Heinrich, L., Schmitt, J., Eberlein-Gonska, M. & Roessler, M. Prediction of inpatient pressure ulcers based on routine healthcare data using machine learning methodology. Sci. Rep.12, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-09050-x (2022).

Facchinello, Y., Beauséjour, M., Richard-Denis, A., Thompson, C. & Mac-Thiong, J.-M. Use of regression tree analysis for predicting the functional outcome after traumatic spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma38, 1285–1291. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2017.5321 (2021).

Goodwin, T. R. & Demner-Fushman, D. A customizable deep learning model for nosocomial risk prediction from critical care notes with indirect supervision. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc.27, 567–576. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaa004 (2020).

Shinkawa, M. et al. A novel skin temperature estimation system for predicting pressure injury occurrence based on continuous body sensor data: A pilot study. Clin. Biomech.122, 106413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2024.106413 (2025).

Ho, J. C., Sotoodeh, M., Zhang, W., Simpson, R. L. & Hertzberg, V. S. An adaboost-based algorithm to detect hospital-acquired pressure injury in the presence of conflicting annotations. Comput. Biol. Med.168, 107754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.107754 (2024).

Wei, L. et al. A machine learning algorithm-based predictive model for pressure injury risk in emergency patients: A prospective cohort study. Int. Emerg. Nurs.74, 101419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ienj.2024.101419 (2024).

Xu, J. et al. Development and validation of a machine learning algorithm–based risk prediction model of pressure injury in the intensive care unit. Int. Wound J.19, 1637–1649. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.13764 (2022).

Dweekat, O. Y., Lam, S. S. & McGrath, L. An integrated system of multifaceted machine learning models to predict if and when hospital-acquired pressure injuries (bedsores) occur. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health20, 828. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010828 (2023).

Xu, J., Chen, T., Fang, X., Xia, L. & Pan, X. Prediction model of pressure injury occurrence in diabetic patients during icu hospitalization——xgboost machine learning model can be interpreted based on shap. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs.83, 103715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2024.103715 (2024).

Chun, X. et al. A model for predicting 7?day pressure injury outcomes in paediatric patients: A machine learning approach. J. Adv. Nurs.77, 1304–1314. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14680 (2020).

Campagnini, S. et al. Cross-validation of predictive models for functional recovery after post-stroke rehabilitation. J. NeuroEng. Rehabil.19, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-022-01075-7 (2022).

Chen, Y.-H. et al. Post-surgical fall risk prediction: a machine learning approach for spine and lower extremity procedures. Front. Med.12, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2025.1574305 (2025).

VanGilder, C. A., Cox, J., Edsberg, L. E. & Koloms, K. Pressure injury prevalence in acute care hospitals with unit-specific analysis: Results from the international pressure ulcer prevalence (ipup) survey database. Journal of Wound, Ostomy & Continence Nursing48, 492–503. https://doi.org/10.1097/won.0000000000000817 (2021).

Levner, I. Feature selection and nearest centroid classification for protein mass spectrometry. BMC Bioinform.6, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-6-68 (2005).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res.12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Zantvoort, K. et al. Estimation of minimal data sets sizes for machine learning predictions in digital mental health interventions. NPJ Digit. Med.7, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01360-w (2024).

Wan, S. & Yang, H. Comparison among methods of ensemble learning. In 2013 International Symposium on Biometrics and Security Technologies, 286–290. https://doi.org/10.1109/isbast.2013.50 (IEEE, 2013).

Dhilsath, F. M. & Samuel, S. J. Hyperparameter tuning of ensemble classifiers using grid search and random search for prediction of heart disease. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119818717.ch8 (2021).

He, J. & Cheng, M. X. Weighting methods for rare event identification from imbalanced datasets. Front. Big Data4, https://doi.org/10.3389/fdata.2021.715320 (2021).

Abdelhamid, M. & Desai, A. Balancing the scales: A comprehensive study on tackling class imbalance in binary classification. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2409.19751 (2024).

Yuan, X., Liu, S., Feng, W. & Dauphin, G. Feature importance ranking of random forest-based end-to-end learning algorithm. Remote Sensing15, 5203. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15215203 (2023).

Chicco, D., Sichenze, A. & Jurman, G. A simple guide to the use of student’s t-test, Mann–Whitney u test, chi-squared test, and Kruskal–Wallis test in biostatistics. BioData Min.18, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13040-025-00465-6 (2025).

Dunn, O. J. Multiple comparisons among means. J. Am. Stat. Assoc.56, 52–64 (1961).

Goel, P. et al. Machine learning based water requirement prediction for agriculture before a rainfall. In 2024 International Conference on Emerging Smart Computing and Informatics (ESCI), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1109/esci59607.2024.10497332 (IEEE, 2024).

Singh, D. & Singh, B. Investigating the impact of data normalization on classification performance. Appl. Soft Comput.97, 105524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2019.105524 (2020).

Cseh, B., Balogh, Z., Takács, J., Túri, G. & Dózsa, C. L. Organizational development and management factors involved in the prevention and effective therapy of pressure ulcers: The results of the national survey conducted among hungarian public hospitals. Int. Wound J.21, https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.14655 (2024).

Jung, Y. K., Hahn, H. M. & Park, D. H. Factors influencing the severity of medical device?related pressure injuries: Pressure injury staging comparison. Int. Wound J.20, 2735–2741. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.14147 (2023).

Sasabe, Y. et al. Deep sedation predicts pressure injury in patients admitted to intensive care units. Nurs. Crit. Care27, 877–884. https://doi.org/10.1111/nicc.12753 (2022).

Barakat-Johnson, M., Barnett, C., Lai, M., Wand, T. & White, K. Incontinence, incontinence-associated dermatitis, and pressure injuries in a health district in australia: A mixed-methods study. J. Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs.45, 349–355. https://doi.org/10.1097/won.0000000000000446 (2018).

Hong, J. E., Shim, M.-O., Choi, H., Been, Y. & Park, S. Factors aggravating the stage of pressure injury in dyspneic patients. J. Tissue Viability34, 100898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtv.2025.100898 (2025).

Ness, M. J., Davis, D. M. R. & Carey, W. A. Neonatal skin care: a concise review. Int. J. Dermatol.52, 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05687.x (2012).

Takashima, M., Hyun, A., Gibson, V., Borello, E. & Ullman, A. Invasive device?associated skin complications and mechanical dysfunctions in paediatric healthcare: A systematic review and meta?analysis. J. Adv. Nurs.80, 4034–4049. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.16073 (2024).

Li, Y., Scheel-Sailer, A., Riener, R. & Paez-Granados, D. Mixed-variable graphical modeling framework towards risk prediction of hospital-acquired pressure injury in spinal cord injury individuals. Sci. Rep.14, 25067 (2024).

Zheng, L., Xue, Y.-J., Yuan, Z.-N. & Xing, X.-Z. Explainable shap-xgboost models for pressure injuries among patients requiring with mechanical ventilation in intensive care unit. Sci. Rep.15, 9878 (2025).

Anderson, C., Bekele, Z., Qiu, Y., Tschannen, D. & Dinov, I. D. Modeling and prediction of pressure injury in hospitalized patients using artificial intelligence. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak.21, 253 (2021).

Shafaf, N. & Malek, H. Applications of machine learning approaches in emergency medicine; a review article. Archives of academic emergency medicine7, 34 (2019).

Voutsas, F., Violos, J. & Leivadeas, A. Mitigating alert fatigue in cloud monitoring systems: A machine learning perspective. Comput. Netw.250, 110543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comnet.2024.110543 (2024).

Sahiner, B., Chen, W., Samala, R. K. & Petrick, N. Data drift in medical machine learning: implications and potential remedies. Br. J. Radiol.96, https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20220878 (2023).

Funding

The research work of Gonzalo Ríos-Vásquez is partially supported by the National Agency for Research and Development (ANID). Scholarship program, Subdirectorate of Human Capital-National Doctorate 2024-code 21240875

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.B.G.: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, software, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing, visualization, supervision. G.R.V.: Methodology, formal analysis, software, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing, visualization. N.F.V.: Data curation, investigation, resources, methodology, writing-review and editing. G.M.T.: Writing-review and editing, language revision. C.A.G.: Supervision, resources, institutional coordination.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted using retrospective, anonymized secondary data originally collected as part of routine clinical care. No personally identifiable information was accessed, and all records were de-identified prior to analysis. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee under Resolution 000-33-1321. In accordance with institutional and national ethical guidelines, the requirement for individual informed consent was waived, as the study involved only secondary, non-identifiable data and did not involve any direct interaction with patients.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Barriga-Gallegos, F., Ríos-Vásquez, G., Tapia, G.M. et al. Early prediction of pressure injury risk in hospitalized patients using supervised machine learning models based on nursing records. Sci Rep 16, 6502 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35709-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35709-w