Abstract

This paper focuses on an effective control technique for enhancing the Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) performance of a grid-connected DFIG-based wind power plant under continuously varying wind conditions. However, rapid fluctuations in wind speeds, uncertainties in parameters, and grid disturbances are key challenges to enhancing the MPPT performance capability. Considering these struggles, this study aims to model a modified dynamic DFIG-based wind turbine system and develop a hybrid Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) with a Proportional-Integral (PI) controller on the back-to-back converter at the rotor and grid sides. The actual limited ranges of wind speed and output power generation data of the Adama II wind power plant in Ethiopia are utilized as input and output variables for the ANFIS controller. The simulation results from the latest version of R2024a-MATLAB-Simulink software show that the proposed ANFIS-PI reached an MPPT of 2.22 MW compared to the FLC-PI controller attained 2.2 MW using the benchmark as the reference value of 1.561 MW in the PI controller, by improving the maximum power coefficient of 0.5504 compared to 0.5473 using the baseline as the reference value of 0.4109, respectively, at a rated wind speed of 12.5 m/s and an optimal pitch angle of 0°.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A global shift toward renewable energy sources is primarily motivated by the pressing need to reduce climate pollution and foster sustainable socio-economic development for improving public health. Among the various renewable energy technologies, wind is a quickly expanding clean source of energy that contributes to large-scale power generation for society1. In today’s technological landscape, the enhanced power harvesting capabilities and standardized control features are the preferred options for further study and investigation in variable-speed wind turbine systems. Because it allows greater flexibility and efficiency in the design and operation of grid-connected Doubly Fed Induction Generator (DFIG)-based wind power plants, aligning energy generation more closely with real environmental conditions. This turbine behavior facilitates maximizing output power by improving the overall efficiency of the entire system2. As reported in the survey of various works summarized in the related literature by3,4,5,6,7,8, to enhance MPPT performance capability by improving maximum power coefficient (Cp max) values. When reviewing the main findings of these publications, the numerical expression of Cp max ranges from 0.3878 to 0.49 at a rated wind speed and an optimal pitch angle.

To obtain these results, the authors employed their unique methodology, which involved modeling the dynamics of a DFIG-based grid-connected wind turbine system, implementing some of the authors’ conventional control techniques, like the Proportional Integral (PI) controllers, and other intelligent control strategies, such as FLC and ANFIS controllers, and simulating the entire system using MATLAB-Simulink software. In a DFIG-based grid-connected wind power plant, the challenge of using the PI controller lies in its inefficiency for enhancing MPPT performance when the system models are characterized by nonlinearity, dynamics, complex higher-order time-delay functions, and variable wind conditions9. Thus, it becomes imperative to use the Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS), considered one of the Artificial Intelligence (AI) optimization methods that combines Fuzzy Logic (FL) and Neural Networks (NNs) to enhance MPPT performance10. In this regard, the FL approach is utilized for rule-based reasoning, and the neural networks serve as an adaptive learning algorithm. So, from these papers, the key gaps identified include the limited use of intelligent control strategies, the lack of standard hybrid controller protocols, and suboptimal overall model designs. Considering the tuning and training algorithm, the authors utilized the PI tuning methods, which include classic trial-and-error tuning, Ziegler-Nichols tuning, and frequency response technique using Bode plots to analyze the gain parameters. In addition, the training and testing algorithm for the ANFIS controller is based on the backpropagation algorithm, the membership functions are trapezoidal, and the number of fuzzy rules does not exceed 25.

According to these reviews, from the researcher’s perspective, the Cp max values are insufficient, and these control strategies present a crucial challenge under continuously varying wind speed conditions, as well as the complexity, nonlinearity, and dynamic nature of the system model. Consequently, these issues are the primary motivation for developing a novel robust hybrid control protocol and a modified DFIG-based grid-connected wind power system model configuration to enhance the MPPT by improving Cp max values at the same wind speed and optimal pitch angle. Thus, in this work, the hybrid ANFIS-PI controller was designed to address the gaps identified in the existing methodology when compared to the hybrid FLC-PI controller using the benchmark as the reference or actual values in the PI controller. In this case, among the various PI tuning methods, use the pole placement technique to analyze the fixed values of the proportional controller gain (kp), integral controller gain (ki), and plant control gain (k). The pole placement technique offers a model-based advantage over classic trial-and-error tuning, Ziegler-Nichols tuning, and frequency response methods by providing direct and precise control over closed-loop system dynamics. It is the most effective analytical method for defining the accurate transient response characteristics, strategically placing the closed-loop poles in the s-plane, and mathematically determining the fixed values of kp, ki, and k to achieve optimal performance metrics, including settling time, rise time, steady-state error, and overshoot. While the Ziegler-Nichols and trial-and-error tuning methods are largely empirical, often leading to aggressive tuning with limited robustness, the frequency response method using Bode plots emphasizes achieving the desired gain and phase margins in the frequency domain.

Furthermore, the ANFIS controller is employed as a hybrid propagation training and testing algorithm to enhance the overall system accuracy when processing real data. The new control architecture of the neural networks trains and creates triangular membership functions by increasing the number of fuzzy rules based on the assigned input variables. The selection of a triangular membership function over trapezoidal and any other types of membership functions is often justified by their computational efficiency and sharper sensitivity to input changes. This design provides more granular and responsive control, as any change in the input immediately alters the degree of membership. Consequently, triangular membership functions generate a more nuanced and smoother output surface, which is particularly advantageous for controlling dynamic and non-linear systems. Moreover, comparing the larger number of fuzzy rules over the simpler rule base enables the system to model more complex, non-linear behaviors with greater precision, better distinctions between operating conditions, optimize key findings, and facilitate context-aware control decisions. Ensuring these will bring a significant reduction in the fluctuation of turbine output power, improve system stability, and increase the overall efficiency of a grid-connected wind power generation.

In addition to designing an effective control strategy, it is also an essential task to choose optimal key components of the Wind Energy Conversion System (WECS), such as a Horizontal-Axis Wind Turbine (HAWT), a Doubly Fed Induction Generator (DFIG), an electronic back-to-back converter, a power transformer, and grid-side filter technologies11.

Nowadays, in the wind industry, the HAWT is becoming one of the most common types of turbines being used in grid-connected Wind Power Plants (WPPs) in both onshore and offshore systems due to its aerodynamic blade design, to capture the optimal energy as efficiently as possible by converting the existing wind flow into rotational motion12. This turbine is typically taller than other turbine types, making it easier to access stronger winds at higher altitudes, which improves overall energy output at variable wind speed conditions13. On the other hand, the HAWT integrated with the rotor of the DFIG-based WPPs operates at variable speeds, being fed by a current at varying frequency through a back-to-back converter. This flexibility enables the turbine to adapt to variable wind speed conditions by ensuring optimal performance and stable power output. This approach minimizes the need for a complex set of converter topologies, prime movers, and heavier gearboxes for grid integration by further reducing mechanical and electrical losses14. The use of an electronic back-to-back converter, power transformer, and filter at the rotor side of a DFIG maintains stability, mitigates harmonic distortions, and hence improves overall power quality of the system, as well as manages the power flow between the generator and the grid15. Additionally, a power transformer plays a vital role in stepping up the generated voltage to meet grid standards16.

Finally, the key added values and contributions of this work is recognizing the enhanced key parameter values such as the maximum power point tracking (MPPT), maximum power coefficient (Cp max), optimal angular speed of the turbine rotor and its equivalent rotational speed of the turbine rotor of the Adama II wind power plant in Ethiopia using the proposed hybrid ANFIS-PI controller through the recent version of R2024a-MATLAB-Simulink software to the core end users throughout the world, such as the wind power plant operators, grid operators, researchers, engineers, innovators, governmental and non-governmental energy utility companies, wind turbine vendors, and others involved in the renewable and sustainable energy sectors by addressing the challenges of integrating a wind power plant into the grid effectively.

Methods

The methodology of this paper is systematically structured to address the research objectives and the main findings. This comprehensive approach comprises several critical components, each designed to contribute to the overall integrity of the system model and the effectiveness of the research process. It encompasses several key elements that are clearly described, as the recent related literature review was conducted, gathered and analyzed the required data, developed a comprehensive dynamic model of the optimal key components of a grid-connected DFIG-based wind power plant, designed a hybrid ANFIS-PI controller, integrated with grid systems, and performance tested and evaluated with the latest MATLAB-Simulink-R2024a software to enhance the MPPT performance capability by improving maximum power coefficient.

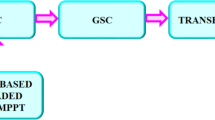

Design of grid-connected DFIG-based wind power plant

The overall system design of the optimal key components and standard control technique for a DFIG-based wind energy conversion system integrated to the electrical grid is depicted in Fig. 117. This includes a HAWT, gearbox, DFIG, electronic back-to-back converter, filter, power transformer, and hybrid ANFIS-PI controller. The system begins with the mechanical input, where the continuously varying wind speed (Vw) is driven to an HAWT. The HAWT captures the kinetic energy of the wind and converts it into mechanical power (Pw) as the turbine rotor spins. This rotational mechanical power is transmitted through a gearbox that adjusts the low-speed, high-torque rotation of the turbine rotor to a higher speed suitable for efficient operation of the DFIG. The stator and rotor windings of the DFIG are actively used for power exchange18. The stator winding is directly connected to the grid through a transformer, and a back-to-back power converter and filter facilitate the integration of the rotor winding with the grid for enhancing stability, reducing harmonics, and ensuring output power quality. A power transformer plays a crucial role in stepping up the voltage generated by the DFIG for efficient transmission to the grid. Additionally, the proposed hybrid ANFIS-PI controller was implemented to enhance output MPPT performance capability and maximize the power coefficient by controlling key control parameters under variable wind conditions, grid disturbances, and parameter uncertainties.

Overall system design of grid-connected DFIG-based wind power plants17.

Mathematical modeling of HAWT

The mathematical modeling of the HAWT represents the turbine aerodynamic, mechanical, and electrical characteristics under variable wind conditions. The aerodynamic model is typically based on Betz’s limit, which calculates the mechanical output power generated by the turbine, and the nonlinear power coefficient depends on the wind speed, blade geometry, and angle of attack19. A theoretical maximum power coefficient (Cp max) of the wind turbine is limited to 0.593, whereas in practical applications, the nonlinear power coefficient (Cp), ranging from 0.108 to 0.49, is used20.

The extracted wind turbine output power (Pw) as a function of the nonlinear power coefficient Cp (λ, β) can be expressed in Eq. (1) as21;

The wind turbine tip speed ratio (λ) can be formulated in Eq. (2) as22;

The function of the nonlinear power coefficient depends on λ and the blade pitch angle (β) calculated in Eq. (3) as23;

Where C1 to C6 are adjusted and unadjusted turbine-specific constant coefficient values, such as C1 = 0.43, C2 = 91, C3 = 0.4, C4 = 5, C5 = 18, and C6 = 0.0287. R is the radius of the rotor, Vw is the wind speed, ρ is the density of air, and wm is the angular speed of the turbine rotor.

The adjusted tip speed ratio (λi) can be defined by Eq. (4) as24;

The dynamic wind turbine-generated torque (Tw) in the rotor of the blade can be obtained by Eq. (5) as25;

The maximum power output (Pw max) that can be extracted from the turbine is calculated in Eq. (6) as26;

Where Cp max is the maximum power coefficient, and Vw rated is the rated speed of the wind.

Wind turbine output power versus wind speed characteristics curve

The nonlinear curve among wind turbine output power in watts versus continuously varying wind speed in meters per second is illustrated in Fig. 2. Typically, the curve consists of three operating points and control regions, marked by dashed lines. The cut-in speed is the minimum wind speed, ranging from 3.02 m/s to 4 m/s, at which the turbine starts to generate power. The rated speed is around 12.5 m/s, and the turbine generates maximum output power27. Cut-out speed is the maximum wind speed, around 25 m/s, at which the turbine will automatically shut down to prevent damage to its components28. The three control regions include below the cut-in speed indicated by region 1where no power is generated; between the cut-in and the rated speed, illustrated as region 2, where the generated power increases as wind speed changes; and between the rated and cut-out speed, as assigned by region 3, where the output power begins to stabilize as wind speed rapidly varies29,30. As a result, in region 2, the Maximum Power Tracking (MPT) is achieved within the continuously varying wind speed range of 3.02 m/s to 12.5 m/s.

Mathematical modeling of DFIG

The three-phase mathematical modeling of a DFIG provides a comprehensive description for analyzing and controlling its behavior, particularly under the dynamic conditions of a wind energy system. The abc-reference frame model describes the three-phase stator and rotor voltage, current, and flux leakage31. The three-phase stator and rotor dynamic voltage derived formulas are represented in Eq. (7) and Fig. 3 as32;

where Vabcs, Vabcr, iabcs, and iabcr are the three-phase voltages and currents, Rs, Rr, Ls, and Lr are the resistances and self-inductances in the stator and rotor windings, respectively.

Three-phase (a) stator and (b) rotor windings of the DFIG electrical equivalent circuit33.

DFIG Dq modeling

The dq-model is the cornerstone for designing the sophisticated standard control strategy in DFIG-based wind turbines. To overcome the complexity of the three-phase model, it is transformed into a dq-reference frame using Park’s transformation techniques. This transformation aligns the time-varying sinusoidal AC quantities into DC values in a steady state, significantly simplifying the control design34.

A derived nonlinear dynamic stator and rotor d-q voltage formulas represented by Eqs. (8, 9) and.

The dq stator and rotor flux leakage are expressed in Eqs. (10, 11) as36;

where Vdqs, Vdqr, idqs, and idqr are the direct and quadrature axis voltage and current, ωs and ωr are the stator and rotor speed, Ψdqs and Ψdqr are the direct and quadrature axis flux leakage in the stator and rotor windings, Ls and Lm are the self and magnetizing inductance.

Two-phase (a) d-axis (b) q-axis stator and rotor of the DFIG equivalent circuit37.

The total power delivered to the grid is the sum of the stator power and the net rotor power after considering the converter losses. A derived nonlinear dynamic active and reactive output power in the stator and rotor windings can be expressed in Eqs. (12, 13) as38;

The nonlinear dynamic electromagnetic torque (Tem) produced by the machine can be given in Eq. (14) as39;

Where Ps and Pr are the active power, Qs and Qr are the reactive power of the stator and rotor windings, respectively, and p is the number of pole pairs.

Mathematical modeling of rotor side converter (RSC) for MPPT

The mathematical modeling of the back-to-back converter involves the dynamics of the two converters and the crucial DC-bus circuit. The rotor and grid voltage and current are changed into a d-q model using abc-αβ-dq transformation techniques. The RSC d-q voltage model under the stator q-axis flux leakage orientation (i.e., Ψqs = 0) is derived from the rotor equations of the DFIG, expressed in Eq. (15) as40;

Where = 1-(Lm2/LsLr) is the leakage coefficient.

Mathematical modeling of Grid-Side converter (GSC) for MPPT

The supplied three-phase grid voltage of the stator winding of a DFIG has a fixed magnitude and frequency. For improving MPPT performance and grid stability. The derived filter voltage at the AC side of the GSC in terms of grid voltage in the d-q components is calculated in Eq. (16) as41;

Where Vdg and Vqg are the d-q grid voltages, Rf and Lf are the filter resistance and leakage inductance, whereas Vdf and Vqf are the d-q filter voltages, and idf and iqf are the d-q filter currents.

As indicated in Eqs. (15, 16), the PI controller can be applied to control the d-q currents by assuming fixed grid quantities and negligible changes in the d-q current and flux leakage.

The derived equation of active and reactive power in the d-q component injected into the filter from the GSC is expressed by Eq. (17) as42;

The derivative of the DC-link voltage (Vdc) is governed by the power balance between the rotor active power (Pr) entering from the RSC and the filter active power (Pf) leaving from the GSC, calculated by Eq. (18) as38,42;

Where Pf and Qf are the active and reactive filter power, C is the DC-link capacitance.

Gearbox dynamic modeling

A gearbox is a mechanical device that transmits power and adjusts the turbine speed and torque through a series of gears. It typically consists of a housing that contains various gears, shafts, and other components. A gearbox is essential in automotive, industrial, and machinery applications, allowing for efficient power transfer and enabling machines to operate at various speeds and loads43. A gearbox is crucial for optimizing the energy conversion process between the HAWT and the DFIG. The gearbox modeling predicts the gearbox’s response under different operating wind speed conditions to enhance performance and efficiency in mechanical systems44. Applying the differential equation to derive the gearbox modeling in terms of electromagnetic torque (Tem), and turbine torque (Tw) of the entire nonlinear dynamic system can be expressed in Eq. (19) as45;

Where ωr is the mechanical rotor speed in the gear, J is the moment of inertia, and B is the friction coefficient.

ANFIS controller modeling for MPPT

Figure 5 presents the overall architecture of the ANFIS controller that contains five hidden layers. The node function within each layer performs specific operations; the adaptive layers contain parameters that are tuned during the learning process, while the fixed layers have no tunable parameters46. Thus, in this work, the real continuously varying wind speed data collected from the Adama II wind power plant in Ethiopia are used as the user-specified input variables X and Y. The variation of this wind speed ranges from 0 m/s to 17.2 m/s. At layer one, or the input fuzzification layer, when the input X is assigned as the minimum range of wind speed (Vw min), which varies from 0 m/s to 1.8 m/s. This consists of six membership functions, as labeled by each adaptive node A1 to Ai. Whereas, the maximum wind speed range (Vw max) is represented by the input variable Y, which changes continuously from 9 m/s to 17.2 m/s and contains seven membership functions as denoted by B1 to Bj. Layer two is the fixed layer, which depicts a set of nodes that apply fuzzy logic operations to combine the inputs from layer one. All nodes in this layer produce forty-two fuzzy rules that contribute to the overall inference process and provide inputs for the next layer. Layer three, or the normalization layer, is also a fixed layer, where the output of the fuzzy rules from layer two is processed. The normalized firing strengths (Wn) are passed to layer four or the consequent layer, which is an adaptive implication layer. Each node in this layer computes a consequent value for a rule and sums the contributions of the fuzzy rules to produce intermediary output values (Zn), which are passed on for further processing. Finally, layer five is a single defuzzification layer and a fixed node that aggregates all the incoming signals from the consequent layer to produce the overall system output (f)47.

The mathematical model of the ANFIS controller based on this typical diagram starts at layer one, which chooses a common generalized bell function to calculate the output of the node (O1i) and (O1j) by Eq. (20) as48;

Where ai, bi, ci, dj, ej, and gj are the triangular membership function premise parameter sets. These adaptive parameters optimize the degree of the membership functions during the training process to minimize the model error. Whereas µ is the fuzzy linguistic values, i = 1, 2…,6, and j = 1, 2…,7.

In layer two, the output of the node (O2n) can be calculated using the multiplication operation on its incoming membership degrees, expressed by Eq. (21) as49;

In layer three, the output of the node (O3n) can be calculated as the normalized firing strength for a rule expressed in Eq. (22) as49;

This crucial step ensures that the sum of the firing strengths is unity, providing a weighted average in the final output layer.

In layer four, the output of the node (O4n) is calculated in Eq. (23) as50;

Where fn is the rule’s linear consequent function, and pn, qn, and rn are the consequent parameter set for that rule. These parameters are also adaptive and tuned during the learning process.

In layer five, the output of the node (O5n = f) is calculated by summing all incoming values represented in (24) as50;

Where Wn is the weighted firing strength, Zn is the normalized firing strength, and n = 1, 2, 3…,42.

Therefore, it can be seen that this is how an adaptive neural network works, specifically as a Sugeno-type Fuzzy Inference System, rather than a Mamdani one, for better model performance accuracy.

PI controller modeling for MPPT

The selection of the fixed values of proportional gain (kp) and integral gain (ki) of the PI controller is based on the DFIG plant model. In a DFIG-based wind turbine MPPT system, the primary objective of this controller in the back-to-back converter is to control the generator’s torque, rotor speed, or dq-axis current to extract maximum power from the wind speed. Thus, the selection of these gain parameters for the PI control system involving the plant model designed to regulate the output y(t) based on a reference input r(t) is represented in Fig. 6. The error signal e(t) is the difference between the reference input and the output. This error is processed through both the kp and ki, which accumulate the error over time. The outputs of these controller gains are summed to form the control signal u(t). Furthermore, an adjusted feedforward plant control gain (k) is incorporated to enhance system effectiveness. As a result, the accurate design and tuning of these key parameters ensure the output tracks the desired reference input effectively, improving the entire system’s optimal performance and stability51. The mathematical plant model for PI tuning is developed based on the relationship between the dq-axis current and voltage from the converter side, as well as the resulting electromagnetic torque and rotor speed of the generator.

A first-order approximation of the ratio of rotor speed of the generator (ωr) and electromagnetic torque (Tem) dynamics is expressed by Eq. (25) as52;

Where Jt is the total moment of inertia of the turbine and generator, B is the damping coefficient, and s is the Laplace variable.

The current control loop in the back-to-back converter, in terms of first-order plus delay time, is calculated by Eq. (26) as53;

Where k is the plant control gain, τ is the time constant, which indicates how fast the system responds, and α is the delay time before the system starts responding.

The combined standard second-order plant model Gp(s) from Eqs. (25) and (26) is represented by Eq. (27) as52,53;

The PI controller model Gc(s) in terms of kp and ki is expressed in Eq. (28) as54;

The proportional up(t) and integral ui (t) functions in terms of the error signal e(t) are expressed by Eq. (29) as55;

The control output u(t) can be formulated by summing the two gains expressed in Eq. (30) as56;

The reference input r(t) is compared with the system output y(t) to calculate the error signal e(t), which is expressed in Eq. (31) as57;

The overall open-loop transfer function, Gol(s), based on the plant model Gp(s) and the PI controller model Gc(s), is calculated by Eq. (32) as52,53,54;

Accordingly, for selecting the fixed values of kp, ki, and k among the various state-space control system design methods, the pole placement technique is the most preferable method in this study.

Based on this method, the closed-loop transfer function Gcl(s) is expressed by Eq. (33) as52,53,54;

Finally, the fixed values of kp, ki, and k calculated using the characteristic equation have their roots at these desired pole locations shown in Eq. (34) as52,53,54;

The specific values of the gain parameters for the PI controller are used as follows: kp = 0.21, ki = 7.2414, and k = 34.483.

Sensitivity analysis for MPPT

Sensitivity analysis in the control system involves evaluating how variations in key input model parameters affect the system’s output and the resulting performance metrics. Sensitivity functions for each parameter with respect to a performance metric (p) expressed in Eq. (35) as58;

Where p is any of the performance metrics like rise time, settling time, steady-state error, or overshoot, and θ represents either kp, ki, or k. Calculating sensitivities of s(p, kp) for metrics like rise time or overshoot, when an increase in kp typically reduces rise time but may increase overshoot. An analysis of s(p, ki) concerning steady-state error indicates that as the value of ki increases, the steady-state error decreases. However, this may result in slower response times and the potential for oscillations. Assessing s(p, k) for overall system effectiveness. Adjusting k can improve performance when the entire system is well-tuned, but may introduce instability if not managed properly.

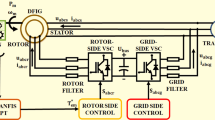

MATLAB-Simulink model of grid-connected DFIG-based wind power plant

The nonlinear masked MATLAB-Simulink model of a grid-connected DFIG-based wind power plant is illustrated in Fig. 7 and the system reference parameter values of the wind power plant is given in Table 1. This model presents multiple interconnected blocks and complex relationships among the various aerodynamic, mechanical, and electrical components, including the RSC current control loop, the MPPT, grid power calculation, DC bus, and GSC control loop models, as well as the associated filter model and their interactions within the overall system. These individual models have unique functions that demonstrate how to optimize MPPT performance by improving the maximum power coefficient value under continuously varying wind conditions, grid disturbances, and parameter uncertainties by controlling the crucial control parameters using the proposed hybrid controller. A complete back-to-back converter model is a multi-input, multi-output system defined by the differential equations of the current, flux leakage, and DC-link voltage for enabling variable-speed operation and bidirectional power flow. It consists of two voltage-sourced converters, the RSC and GSC, interconnected by a common DC bus circuit. The primary function of the RSC and GSC is to control the rotor and grid currents for maintaining stable torque and active and reactive power output. The RSC typically converts the sinusoidal AC from the DFIG into a DC voltage, and the GSC converts the DC voltage from the RSC into an AC voltage suitable for grid integration. A grid filter is used at the GSC output to ensure the current injected into the grid, maintaining power quality standards by reducing total harmonic distortions.

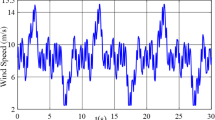

The highly variable and intermittent nature of the Adama II wind power plant’s real wind speed profile data is presented in Fig. 8. These variable input resources are crucial for enhancing the MPPT performance capability and other related optimal output parameter values. These wind speeds do not settle at a steady-state value but continuously fluctuate within the wide range of 0 m/s to 17.2 m/s throughout the observed time. These types of transient behavior are critical for understanding the dynamic mechanical loads on turbine blades and the challenge of converting a rapidly variable wind energy source into stable electrical power for the grid. Therefore, this graph effectively illustrates the inherent instability of wind speed conditions that directly affect wind power generation, which presents a significant consideration for turbine design and control systems.

ANFIS controller MATLAB simulink model for MPPT

Figure 9 illustrates the minimum and maximum ranges of wind speed values that serve as input variables to the ANFIS controller, with the output being the maximum range of turbine output power. The ANFIS controller, depicted in the center labeled Sugeno-type fuzzy inference system, processes these inputs to generate an output function, denoted as f(u), which ultimately determines the turbine’s output power.

The generated input membership functions (MFs) during the training and testing processes are shown in Fig. 10a and b. Both graphs have a similar triangular structure, with the horizontal axis representing the input variables that range from 0 to 1.8 for Figs. 9 and 10a to 17.2 for Fig. 10b, and the vertical axis indicates membership values that range from 0 to 1. The first and second input variables consist of six and seven MFs, respectively, that are labeled as Extremely Weak (EW), Very Weak (VW), Weak (W), Medium (M), Fast (F), and Very Fast (VF), but in Fig. 10b add one additional MF that is assigned by Extremely Fast (EF), indicating the different fuzzy set categories to which the input variable can belong.

The connection of the five-layer structure demonstrates how the ANFIS framework combines fuzzy logic with neural networks, utilizing the logical operations to model complex relationships and optimize turbine output under continuously fluctuating wind conditions, as illustrated in Fig. 11. It shows two input variables associated with thirteen membership functions, which are processed through a comprehensive set of forty-two rules controlling their interactions. Additionally, using all the necessary system reference values of the ANFIS controller from Table 2 and forty-two output functions to generate a single output.

Results

The MATLAB simulation results of the wind turbine output power (Pw) and the related parameters, such as the nonlinear power coefficient (Cp), angular speed of the turbine rotor (wm), and its equivalent rotational speed of the turbine rotor (N), are demonstrated in Figs. 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 and 19. At the start of the simulation, the three controllers showed a sharp rise, indicating an initial transient phase. Subsequently, due to the continuous variation of wind speed conditions, all parameter values reached and settled at their maximum operating limits, known as saturation levels. The effectiveness of the proposed hybrid ANFIS-PI controller in maximizing output power capture is directly evidenced by its optimal control of this nonlinear power coefficient (Cp). As the primary determinant of the turbine output power (Pw) performance efficiency expressed in Eq. (1), among the listed parameters, the Cp and the variable wind speed (Vw) are the most critical values. Accordingly, the Cp simulation graph visually illustrates that improved tracking values achieved by the ANFIS-PI controller directly contribute to an increase in the turbine output power captured from the wind speed. This optimal Cp indicates that both the wm and N of the turbine rotor are effectively regulated in comparison to their reference values, ensuring that the turbine continuously operates at its peak output power point tracking. According to Eq. (1) to (5), when the wind speed changes continuously, as illustrated in Fig. 8, the parameter values listed above also change. When simulating wind speed variations over 10 s, changing from 0 m/s to 17.2 m/s, all the obtained results are positive output values that fluctuate continuously throughout these durations. Those results show too many variations, particularly in the proposed hybrid ANFIS-PI controller when compared to the FLC-PI controller using the benchmark as the reference values in the PI controller. These clearly indicate that the performance analysis of the computational complexity for those controllers does not demonstrate oscillations and ripples; rather, it reflects the results themselves. Those fluctuations arise from the continuously varying wind speed conditions, as well as the complexity, nonlinearity, and dynamic nature of the overall model. Thus, the results show that using the PI controller likely exhibits the lower performance improvement, in some cases, similar to linear results, due to its fixed gain parameters, which cannot adapt to the nonlinear aerodynamic characteristics, and the lack of variability at the wind speed conditions. The results in the hybrid FLC-PI controller demonstrate better performance enhancement over the PI through its rule-based adaptation. When compared to the FLC-PI controller within the ANFIS-PI controller, it has noticeably less performance because the predefined fuzzy rules may not fully capture the complex, nonlinear dynamics of the wind turbine system across all operating regions. Based on the use of real data, the proposed hybrid ANFIS-PI controller achieves the best performance enhancement by adapting to the nonlinear aerodynamic characteristics and properly tuning the PI gain parameters through the combination of the learning capability of neural networks and the logical reasoning ability of fuzzy logic rule-based systems.

So, the numerical values of those parameters, such as the wind turbine output power (Pw), described in Figs. 12 and 16, which vary from 0.54 MW to 2.22 MW in ANFIS-PI controller, as compared to 0.538 MW to 2.2 MW in FLC-PI controller, when the benchmark as the reference values change from 0.31 MW to 1.561 MW using the PI controller. Figures 13 and 17 illustrate the nonlinear power coefficient (Cp) values, which change from 0.151 to 0.5504 for the ANFIS-PI controller compared to 0.1507 to 0.5473 for the FLC-PI controller using the baseline as the reference values that vary from 0.108 to 0.4109 in the PI controller. The values of angular speed of the turbine rotor (wm) change from 63.19 rad/s to 162.1 rad/s in the ANFIS-PI controller, as compared to 63.17 rad/s to 161.7 rad/s in the FLC-PI controller, when the benchmark as the reference values, which change from 63.094 rad/s to 159.06 rad/s in the PI controller, are presented in Figs. 14 and 18. Additionally, Figs. 15 and 19 demonstrate that the rotational speed of the turbine rotor (N) in the ANFIS-PI controller varies from 603.42 rpm to 1,547.941 rpm compared to the FLC-PI controller, which changes from 603.229 rpm to 1,544.121 rpm using the baseline as the reference values that fluctuate from 602.503 rpm to 1,518.911 rpm in the PI controller. All parameter values were achieved under continuously varying wind speed (Vw) conditions, as described in Fig. 8 and within the various pitch angle values.

Discussions

The reference values from the PI controller are used in the simulation results, rather than those from other controllers, because the control strategy implemented by the Adama II wind power plant is the PI controller, as verified by the collected real data. The reference numerical values in the PI controller of this power plant indicate that the maximum turbine output power, maximum power coefficient, optimal angular speed of the turbine rotor, and its equivalent rotational speed of the turbine rotor under a rated wind speed of 12.5 m/s, and an optimal pitch angle (βopt) of 0° are illustrated in Table 3. Based on this data, from the researcher’s perspective, these reference values are inadequate, and this control strategy poses a crucial challenge under continuously changing wind speed conditions, as well as due to the complexity, nonlinearity, and dynamic nature of the system model. Consequently, these issues are the primary motivation for developing a novel robust hybrid control protocol to enhance the MPPT values of this power plant by improving the maximum power coefficient (Cp max) values at the same wind speed and an optimal pitch angle.

Thus, in this work, to address the identified gaps in the current methodologies, a robust hybrid ANFIS-PI controller was designed to enhance the MPPT performance by improving the maximum power coefficient and the other related peak output parameter values, compared to the hybrid FLC-PI controller, using the benchmark of the reference values from the PI controller. Since maximum power tracking (MPT) is primarily achieved in the second region of the wind turbine output power versus wind speed characteristics curve, as shown in Fig. 2, where the wind speed varies in the range of 3.02 m/s to 12.5 m/s. Thus, to obtain the turbine maximum output power (Pw max) or MPPT and the mentioned optimal output values by substituting into Eq. (6), from the continuously varying real wind speed profile data as described in the results section, the wind speeds of 9.34 m/s and 12.5 m/s were utilized at the optimal pitch angle of 0°. Accordingly, Fig. 12 depicts the MPPT output performance of the wind turbine, revealing that the ANFIS-PI controller reaches a slightly higher value of 2.22 MW when compared to the FLC-PI controller achieves a peak value of 2.2 MW using the benchmark as the reference value of 1.561 MW in the PI controller at a rated wind speed of 12.5 m/s with an optimal pitch angle of 0°. Maintaining an optimal pitch angle of 0° and at 12.5 m/s, the wind turbine’s maximum power coefficient (Cp max) reaches a slightly higher value of 0.5504 in the ANFIS-PI controller, when compared to 0.5473 for the FLC-PI controller using the benchmark as the reference value of 0.4109 in the PI controller, as shown in Fig. 13. Figure 14 illustrates that the nominal angular speed of the turbine rotor in the ANFIS-PI controller reaches approximately 162.1 rad/s, compared to 161.7 rad/s in the FLC-PI controller using the benchmark as the reference value of 157.08 rad/s from the PI controller at a wind speed of 12.5 m/s with a pitch angle of 0°. At 12.5 m/s and 0°, Fig. 15 shows that the ANFIS-PI controller achieves a slightly higher optimal rotational speed of the turbine rotor, at 1,547.94 rpm, compared to 1,544.12 rpm for the FLC-PI controller. This comparison uses the benchmark reference value of 1,500.0035 rpm in the PI controller. Figure 16 illustrates that the MPPT output performance from the turbine with the ANFIS-PI controller reaches 1.919 MW, compared to the FLC-PI controller, which achieves an impressive 1.891 MW using the benchmark as the reference value of 1.359 MW from the PI controller at 9.34 m/s with a pitch angle of 0°. For a wind speed of 9.34 m/s and the same angle, the wind turbine’s maximum power coefficient in the ANFIS-PI controller attains a slightly notable value of approximately 0.5439 when compared to 0.5413 reached in the FLC-PI controller using the baseline as the reference value of 0.4098 in the PI controller, as shown in Fig. 17. The nominal angular speed of the turbine rotor for the ANFIS-PI controller reaches approximately 161.1 rad/s, compared to 160.9 rad/s for the FLC-PI controller. This comparison uses the baseline reference value of 159.06 rad/s from the PI controller at 9.34 m/s with the same pitch angle, as illustrated in Fig. 18. Moreover, Fig. 19 indicates that the nominal rotational speed of the turbine rotor for the ANFIS-PI controller achieves a value of 1,538.39 rpm compared to 1,536.48 rpm reached for the FLC-PI controller. This comparison uses the benchmark as the reference value of 1,518.911 rpm from the PI controller at 9.34 m/s with a pitch angle of 0°.

The comparative analysis of the main results between the proposed hybrid ANFIS-PI controller and the FLC-PI controller, utilizing the benchmark reference value from the PI controller, is summarized in Tables 4 and 5. This analysis focuses on enhancing the maximum output power performance capability by improving the maximum power coefficient of the turbine.

Conclusions

This paper summarizes the enhancement of the MPPT performance of a grid-connected Doubly-Fed Induction Generator (DFIG)-based wind power plant under continuously fluctuating wind speed conditions. The proposed hybrid ANFIS-PI controller was implemented on the back-to-back converter at the rotor and grid sides to address the identified gaps in the existing methodologies. Since the actual numerical values in the PI controller of the Adama II wind power plant in Ethiopia indicate that the maximum turbine output power is 1.56 MW, achieved at a maximum power coefficient of 0.41, under a rated wind speed of 12.5 m/s and an optimal pitch angle of 0°, this taken as the critical benchmark reference values for enhancing the MPPT performance capability. Thus, the simulation result in Fig. 12 clearly demonstrates that the actual output power closely matches the reference output power, with only a minimum deviation. The reason for using the reference values from the PI controller in the simulation results, rather than any other controllers, is that the control strategy employed by this power plant is the PI controller, as confirmed by the collected real data. Based on this data, from the researcher’s perspective, these reference values are inadequate, and this control strategy poses a crucial challenge under continuously changing wind speed conditions, as well as due to the complexity, nonlinearity, and dynamic nature of the system model.

Therefore, this work aims to achieve an enhanced turbine maximum output power of 2.22 MW in the proposed hybrid ANFIS-PI controller as compared to 2.2 MW in the hybrid FLC-PI controller by improving the maximum power coefficient to 0.5504 compared to 0.5473, respectively, under the same rated wind speed of 12.5 m/s and an optimal pitch angle of 0° using the latest version of R2024a-MATLAB-Simulink software. Accordingly, the wind speeds of 9.34 m/s and 12.5 m/s, as well as all wind speed values taken from Fig. 8, the proposed hybrid ANFIS-PI controller offers the best enhanced MPPT performance results and an improved tracking of the other related peak output parameter values.

In conclusion, the performance analysis of the computational complexity results shows that using the PI controller likely exhibits the lower performance improvement, in some cases, similar to linear results, due to its fixed gain parameters, which cannot adapt to the nonlinear aerodynamic characteristics, and the lack of variability at these wind speed conditions. The results in the hybrid FLC-PI controller demonstrate better performance enhancement over the PI controller through its rule-based adaptation. When compared to the FLC-PI controller within the ANFIS-PI controller, it has noticeably less performance because the predefined fuzzy rules may not fully capture the complex, nonlinear dynamics of the wind turbine system across all operating regions. Based on the use of real data, the proposed hybrid ANFIS-PI controller achieves the best performance enhancement by adapting to the nonlinear aerodynamic characteristics and properly tuning the PI gain parameters through the combination of the learning capability of neural networks and the logical reasoning ability of fuzzy logic rule-based systems. Finally, the design process of the proposed hybrid ANFIS-PI controller can be applied for other specific location wind farms by retraining the ANFIS module with local data and re-tuning the PI gain parameters under different turbine characteristics, grid conditions, or wind profiles. However, this work is limited to enhancing MPPT performance by maximizing all related output parameter values under balanced operational conditions and continuously varying wind speeds, without addressing the fault ride-through capability under unbalanced operational conditions. For next research, it is recommended to test the generalizability of results by applying hybrid controller in various grid-connected wind power plants located in different environments, under both balanced and unbalanced operational conditions, as well as continuously varying wind speeds.

Contributions

The contributions of this work are highly relevant to the core end users throughout the world, including wind power plant operators, grid operators, researchers, engineers, innovators, governmental and non-governmental energy utility companies, wind turbine vendors, and others involved in the renewable and sustainable energy sectors. The key contributions are listed as follows: it designs a robust hybrid ANFIS-PI controller to enhance MPPT performance capability by addressing the challenges of integrating a wind power plant into the grid effectively. It provides comprehensive simulation results that demonstrate the robustness of the proposed controller compared to the hybrid FLC-PI controller using the benchmark as the reference and actual values in the PI controller through the recent version of MATLAB Simulink R2024a software. Finally, it is important to recognize the enhanced key parameters, such as maximum power point tracking (MPPT), maximum power coefficient (Cp max), optimal angular speed of the turbine rotor, and the rotational speed of the turbine rotor for power plant under continuously varying wind speed conditions.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Munguia, F. E., Robles, M. & Garcia, H. Rodríguez-Hernández,O. Improvement in output power assessment by wind turbine power curve modeling based on data mining. AIP Adv. 13, 7 (2023).

Chaudhuri, A., Datta, R., Kumar, M. P., Davim, J. P. & Pramanik, S. Energy conversion strategies for wind energy systems in electrical, mechanical, and material aspects. Mater. Basel. 15, 1–36 (2022).

Bekiroglu, E. & Yazar, M. D. MPPT control of Grid-Connected DFIG at variable wind speed. Energies 15, 9 (2022).

Pande, J., Nasikkar, P., Kotecha, K. & Varadarajan, V. A review of maximum power point tracking algorithms for wind energy conversion systems. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 9, 1–30 (2021).

Chhipa, A. A. et al. Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy inference System-Based maximum power tracking controller for variable speed WECS. Energies 14, 6275 (2021).

Yessef, M. et al. Improving the maximum power extraction from wind turbines using a Second-Generation CRONE controller. Energies 15, 3644 (2022).

Chhipa, A. A. et al. Modeling and control strategy of wind energy conversion system with Grid-Connected Doubly-Fed induction generator. Energies 15, 6694 (2022).

Elnaghi, B. E. et al. Experimental validation of Second-Order adaptive fuzzy logic controller for Grid-Connected DFIG wind power plant. IEEE Access. 11, 135255–135271 (2023).

Zhang, Y. & Jiang, T. Robust predictive rotor current control of a doubly fed induction generator under an unbalanced and distorted grid using a PI controller. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 37 (1), 433–442 (2021).

Vargas, O. S. et al. Adaptive Network-Based fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) applied to inverters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 39, 869–884 (2024).

Aljafari, B., Stephenraj, J. P., Vairavasundaram, I. & Rassiah, R. S. Steady state modeling and performance analysis of a wind Turbine-Based doubly fed induction generator system with rotor control. Energies 15, 9 (2022).

Elkodama, A. A. et al. Control methods for horizontal axis wind turbines (HAWT): State-of-the-Art review. Energies 16, 17 (2023).

Raouf, A., Tawfiq, K. B., Eldin, E. T., Youssef, H. & El-Kholy, E. E. Wind energy conversion systems based on a synchronous generator: comparative review of control methods and performance. Energies 16, 5 (2023).

Solomin, E. V. & Ryavkin, G. N. Horizontal axis wind turbine weather Vane aerodynamic characteristics: delayed detached eddy simulation and experimental approach. Mathematics 11, 8 (2023).

Arifin, M. S. & Uddin, M. N. Dynamic stability analysis of a simplified Neuro-Fuzzy direct torque control scheme for a Grid-Connected DFIG-WECS with improved performance and reduced computation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 60, 8482–8494 (2024).

Blecharz, K., Ryndzionek, R. & Kutt, F. Modeling and control of a brushless multiphase Doubly-Fed induction generator in a Stand-Alone wind generation system. IEEE Access. 12, 122340–122349 (2024).

Chojaa, H. et al. Robust control of DFIG-based WECS integrating an energy storage system with intelligent MPPT under a real wind profile. IEEE Access. 11, 90065–90083 (2023).

Gianto, R. Constant voltage model of DFIG-based variable speed wind turbine for load flow analysis. Energies 14, 24 (2021).

Haile, E. A., Worku, G. B., Beyene, A. M. & Tuka, M. B. Investigation of the effects of uncertain weather conditions on the power generation ability of wind turbines. Reliable Theory Appl. 16, 258–274 (2021).

Sarathi, J., Prabha, D. R. & An Effective, A. N. F. I. S. Approach for interconnected DFIG-Based wind energy system with Model-In-Loop validation. IEEE Access. 13, 77147–77164 (2025).

Behara, R. K. & Saha, A. K. Artificial intelligence control system applied in smart grid integrated doubly fed induction Generator-Based wind turbine: A review. Energies 15, 17 (2022).

Ismail, K. A. et al. Review of small Horizontal-Axis wind turbines. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 49, 1367–1391 (2024).

Haile, E. A., Worku, G. B., Beyene, A. M. & Tuka, M. B. Modeling and control of wind energy conversion system (WECS) for performance enhancement. Int. J. Dyn. Control. 12, 891–914 (2024).

Haile, E. A., Worku, G. B., Beyene, A. M. & Tuka, M. B. Upwind horizontal axis wind turbine output power optimization via artificial intelligence control system. Autom. Control Intell. Syst. 9, 6 (2021).

Nouriani, A. & Moradi, H. Variable speed wind turbine power control: A comparison between multiple MPPT-based methods. Int. J. Dyn. Control. 10, 654–667 (2022).

Bilendo, F. et al. Applications and modeling techniques of wind turbine power curve for wind farms: A review. Energies 16, 1 (2023).

Dal, M. & Kennel, R. M. A dynamic modeling approach: simplifying DFIG Theory, Simulation, and analysis. Energies 18, 2 (2025).

Babayomi, O., Li, Y., Zhang, Z. & Park, K. B. Advanced control of Grid-Connected microgrids: Challenges, Advances, and trends. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 40, 7681–7708 (2025).

Han, B., Xie, H., Shan, Y., Liu, R. & Cao, S. Characteristic curve fitting method of wind speed and wind turbine output based on abnormal data cleaning. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2185, 1 (2022).

Eminoglu, U. & Turksoy, O. Power curve modeling for wind turbine systems: a comparison study. Int. J. Ambient Energy. 42, 1912–1921 (2021).

Umar, D. A. et al. Evaluating the efficacy of intelligent methods for maximum power point tracking in wind energy harvesting systems. Processes 11, 5 (2023).

Haile, E. A., Worku, G. B., Beyene, A. M. & Tuka, M. B. Modeling of a doubly fed induction generator-based wind energy conversion system and speed controller. J. Energy Syst. 5, 46–59 (2021).

Mahmoud, M. M., Atia, B. S., Abdelaziz, A. Y. & Aldin, A. N. Dynamic performance assessment of DFIG-Based WECS with the support of Manta ray foraging optimizer considering MPPT, pitch Control, and FRT capability issues. Processes 10, 12 (2022).

Zahraa Magdy, F. E. et al. Optimal artificial intelligence technique for LVRT capability improvement of a Grid-tied wind energy conversion system: A MGOANFIS-PI methodology. Ain Shams Eng. J. 15, 8, 102876 (2024).

Blaabjerg, F., Chen, M. & Huang, L. Power electronics in wind generation systems. Nat. Rev. Electr. Eng. 1, 234–250 (2024).

Hannan, M. A. et al. Wind energy Conversions, Controls, and applications: A review for sustainable technologies and directions. Sustain 15, 5 (2023).

Almihat, G. M. & Kahn, M. T. Wind turbines control trends and challenges: an overview. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Stud. 5, 378–390 (2022).

Patel, K., Dunstan, T. D. & Nishino, T. Time-dependent upper limits to the performance of large wind farms due to mesoscale atmospheric response. Energies 14, 1–16 (2021).

Ganthia, B. P. & Barik, S. K. Fault analysis of PI and Fuzzy-Logic-Controlled DFIG-based Grid-Connected wind energy conversion system. J. Inst. Eng. Ser. B. 103, 415–437 (2022).

Bruno, G. S., Mansour, D. E., Nada, A. & Megahed, T. F. Hybrid ANN-Based MPPT control for DFIG wind systems using Type-2 fuzzy logic and Super-Twisting sliding mode control. Smart Grids Sustain. Energy. 10, 2 (2025).

Gil-García, I. C., Fernández-Guillamón, A. & Montes-Torres Á. H. Innovation in clean energy from man-made wind and small-wind generation. Sci. Rep. 14, 22932 (2024).

Boutaghane, K. et al. Using new control strategies to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the hybrid power system based on the battery storage system. Sci. Rep. 15, 1–32 (2025).

Teklehaimanot, Y. K., Akingbade, F. K., Ubochi, B. C. & Ale, T. O. A review and comparative analysis of maximum power point tracking control algorithms for wind energy conversion systems. Int. J. Dyn. Control. 12, 3494–3516 (2024).

Al-Dhaifallah, M., Saif, A. W., Elferik, S., Elkhider, S. M. & Aldean, A. S. Combining sliding mode and Fractional-Order theory for maximum power point tracking enhancement of Variable-Speed wind energy conversion. Fractal Fract. 8, 8 (2024).

Rehimi, S., Bevrani, H., Urabe, C. T. & Kato, T. Grid forming converter control system synthesis: A static output feedback approach. IEEJ Trans. Electr. Electron. Eng. 19, 1156–1167 (2024).

Acharya, S. et al. Enhanced grid integration in hybrid power systems using ANFIS-based distributed controllers. Int. J. Inf. Technol. 17, 2271–2285 (2025).

Boudjemai, H. et al. Design, Simulation, and experimental validation of a new fuzzy Logic-Based maximal power point tracking strategy for low power wind turbines. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 26, 2567–2584 (2024).

Tabbussum, R. & Dar, A. Q. Performance evaluation of artificial intelligence paradigms: artificial neural networks, fuzzy logic, and adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system for flood prediction. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 28, 25265–25282 (2021).

Aruna, R. & Balaraman, D. S. Fuzzy logic Control-Based maximum power point tracking for wind energy conversion system. Int. J. Adv. Res. Sci. Commun. Technol. 6, 760–767 (2021).

Arifin, M. S., Uddin, M. N. & Wang, W. Neuro-fuzzy adaptive direct torque and flux control of a grid-connected DFIG-WECS with improved dynamic performance. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 59 (6), 7692–7700 (2023).

Chetouani, E. et al. Optimal tuning of PI controllers using adaptive particle swarm optimization for a doubly-fed induction generator connected to the grid during a voltage dip. Bull. Electr. Eng. Inf. 10 (5), 2367–2376 (2021).

Mohapatra, S. P. & Dash, P. K. A novel control strategy of a variable-speed doubly-fed-induction-generator-based wind energy conversion system. Clean. Energy. 8 (1), 153–170 (2024).

Subha Seethalakshmi, V., Praveen, B. M. & Vengadachalam, N. Small-signal stability analysis using Kookaburra optimization for a wind turbine with a doubly fed induction generator. J. Chin. Inst. Eng. 48 (1), 1–18 (2025).

Noureddine, S., Morsli, S. & Tayeb, A. Optimized fuzzy fractional PI-based MPPT controllers for a variable-speed wind turbine. Wind Eng. 46 (6), 1721–1734 (2022).

Bahgat, M., Ezzat, M., Attia, M. A., Mekhamer, S. F. & Elbehairy, N. M. Comparative analysis of PI and fuzzy logic controller for grid-connected wind turbine under normal and fault conditions. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 1954 (2025).

Nasim, F. et al. Hybrid ANFIS-PI-Based optimization for improved power conversion in DFIG wind turbine. Sustainability 17 (6), 2454 (2025).

Sahito, G. M. et al. Design of PI controller for wind energy conversion system using MATLAB/Simulink. Int. J. Electr. Engg Emerg. Technol. 5 (2), 6–10 (2022).

Şenol, B. & Demiroğlu, U. Optimizing PI controller for stability and overshoot in step response using GA and PSO Techniques, A comparative study. Int. Sci. Vocat. Stud. J. 9 (1), 12–23 (2025).

Makeyaw, A. & Getu, M. Unlocking ethiopia’s renewable energy potential: pathways into a sustainable future. Renew. Energy Focus. 48, 102–115 (2025).

Acknowledgements

Bonga University, Bonga, Ethiopia, and Addis Ababa Science and Technology University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, are acknowledged for providing a joint Ph.D. Scholarship to the first author during this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.W. Biyazne was responsible for tasks including conceptualization, methodology, data collection, system design, modeling, investigation, validation, preparation of the original draft, formal analysis of results, and manuscript writing. M.B. Tuka, and A. Wellhöfer contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, writing, editing, analysis, validation, visualization of the review and supervision and Y.M. Abebe involved mainly in supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Biyazne, L.W., Tuka, M.B., Abebe, Y.M. et al. Enhancing MPPT performance of a grid-connected Doubly-Fed induction generator-based wind power plant using hybrid ANFIS-PI control strategy. Sci Rep 16, 5732 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36021-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36021-3